I’ve tried multiple ways to track what I found interesting in the mega-fields of science and technologies. And I failed. So I now plan to log only titles and links of the things I think are really important, and let ChatGPT do the digging if I need something specific.

However, every few years I plan to prune the old tree, and just keep the fruitiest of links.

2026

2026.03.03 1440 has a short introduction on one of the most common renewable energy sources, Solar Power. These are technologies that capture radiant energy from sunlight and convert it into electricity or thermal energy. Solar is part of an emerging class of renewable energy sources that can diversify a region’s or nation’s power generation portfolio while reducing reliance on fossil fuels (explore global solar resources).

Solar power harnesses radiation from the sun to generate electricity, typically through devices known as photovoltaics—commonly referred to as solar panels. When light falls on photovoltaic materials, it is absorbed by electrons, making them conductive, much like the electrons flowing through a metal wire (watch explainer). Concentrated solar power systems instead use fields of mirrors to redirect sunlight toward a thermal fluid, which heats up. The fluid is used to turn water into steam, which spins a turbine connected to a generator to produce electricity (watch explainer).

Since their development, solar cells have become faster, more efficient, and cheaper, with costs decreasing from roughly $1,500 per watt in the 1950s to less than $1 per watt today. This has made solar power the fastest-growing source of electricity in the US (view data).

Learn even more by exploring all our findings on solar power here.

Here’s a sample of what we found …

> Solar power was harnessed for heating and cooling 6,000 years ago. (Read)

> A 1,000-square-kilometer patch of solar panels in Africa could power most of Europe. (Watch)

> How solar power complicates energy management on the electric grid. (Watch)

> See how solar panels are manufactured. (Watch)

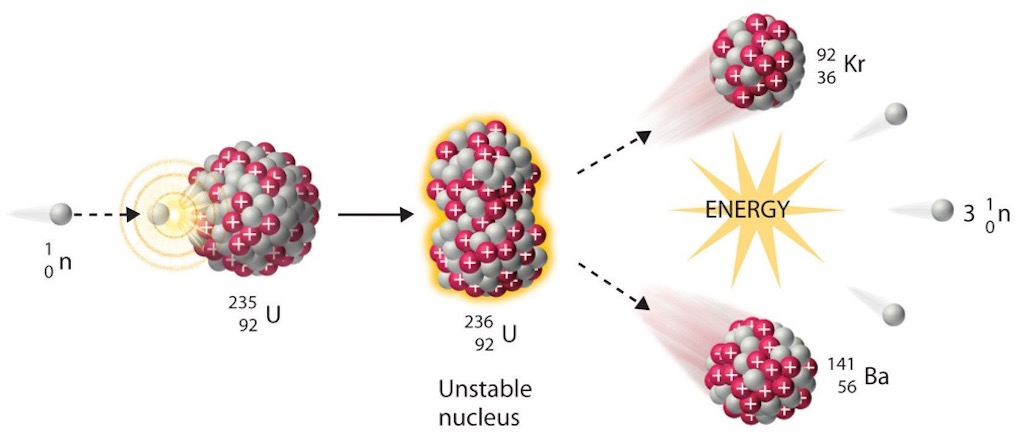

2026.03.03 1440 has a short introduction on Particle accelerators, which are machines that accelerate and steer beams of charged particles, such as electrons, into collisions with one another or with another target. More than 30,000 exist worldwide, with most used to sterilize medical equipment, produce radiopharmaceuticals for cancer therapy, and detect chemical contaminants (explore uses).

Based on the path taken by particles, they are categorized as either linear accelerators (linacs) or circular accelerators. Both types include four key components: a source that produces charged particles, electric fields to accelerate them, magnetic fields to steer and focus them, and a vacuum within which they can travel unobstructed to their target (see diagram).

Particle accelerators are sometimes referred to as “atom smashers” because the first generation of these devices used atoms as collision targets rather than subatomic particles (learn more). Today, the largest accelerators most often use protons to probe subatomic structures and the origins of the universe by reaching temperatures in the trillions and accelerating matter up to 99.9999991% the speed of light (learn how).

Learn even more by exploring all our findings on particle accelerators here.

Here’s a sample of what we found …

> In 1971, a $35 ferret helped clean the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. (View)

> A 36-year-old physicist survived a particle accelerator beam to the head. (Watch)

> The particle accelerator analyzing art at the Louvre. (View)

> Take a 3D tour of the Large Hadron Collider’s particle detector. (Watch)

1016.02.10 440 has a short introduction to LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. It consists of two detectors in Hanford, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana, built to observe gravitational waves produced by astronomical phenomena. Like ripples created by objects traveling along water, gravitational waves are ripples produced by objects moving through spacetime (watch explainer). Unlike light, which can be blocked by matter, gravitational waves travel at the speed of light unimpeded, allowing scientists to use LIGO to study otherwise invisible cosmic events (e.g. black holes).

Each detector has two 4-kilometer (2.5-mile) tunnels called arms, which form an “L” shape (see diagram). During each experimental run, a continuous laser beam is split at the point where the arms connect, with each half sent down an arm. The beams reflect off mirrors—one at the end of the arm and one near where they connect—about 300 times before recombining. A passing gravitational wave will cause the recombined beam to produce a specific pattern, which is compared to those made in simulations to determine the characteristics of the cosmic event that created the waves (watch explainer).

Requiring extensive flat land, minimal seismic activity, and enough space between them to rule out false positives from the local environment, LIGO detectors were built 3,002 kilometers (1,865 miles) apart. Since going online in 2015 after a series of upgrades, LIGO has detected mergers involving black holes and neutron stars and validated predictions made by Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking.

Learn even more by exploring all our findings on LIGO here.

Here’s a sample of what we found …

> In 1974, a pair of neutron stars provided the first evidence of gravitational waves. (Read)

> Listen to the first gravitational wave signal ever detected by LIGO. (Watch)

> How a quantum property helps LIGO improve its signal sensitivity. (Watch)

> Try to catch the “sound” of black holes in gravitational wave detector data. (Explore)

2026.02.25 The Man Who Stole Infinity is about Georg Cantor proving that there are different sizes of infinity. Some newly unearthed letters may suggest otherwise, and this is a well written review of what those letter might suggest.

And dated 2026.02.23 is How Can Infinity Come in Many Sizes?, is all about how some infinities are bigger than others.

2026.02.17 1440 has a short introduction to Computer Viruses, which are a type of code that copies itself into other software when a user runs an infected program or file. This action causes damage by altering programs, corrupting files, and compromising digital security (learn more). The term was first used in 1984 to describe all types of self-duplicating software and has since been misused as a catchall for a broad range of malicious software, including adware and spyware (malware types, explained). However, computer viruses are distinct from other malware because they require human action to spread.

The idea of self-replicating software originated with John von Neumann, a mathematician and computer scientist who worked on the Manhattan Project. The first computer virus to spread beyond a research lab, Elk Cloner, was written by 15-year-old Richard Skrenta and spread through floppy disk sharing (learn more). Subsequent viruses also propagated via physical media, but the widespread adoption of the internet led to infections occurring more commonly through the downloading of software, such as compromised email attachments (explore examples).

Software developed to detect and remove early computer viruses became the precursors to modern antivirus software—a misnomer for tools used to protect against all forms of malware (learn how to avoid them). Computer viruses have become increasingly rare due to these tools, more secure computing architecture (e.g., web-based programs that don’t need to be downloaded), and the shift by cybercriminals toward more lucrative methods, such as ransomware.

Learn even more by exploring all our findings on computer viruses here.

Here’s a sample of what we found …

> The Melissa “virus” helped associate explicit websites with malware. (Watch)

> Some viruses can transform or hide inside Microsoft Office files. (View)

> The history of malware and how AI will impact its future. (Watch)

> Take a guided tour through the Museum of Malware Art. (Watch)

2026.01.22 Just a reminder that Quanta Magazine has a YouTube channel with lots of great video tutorials. For example, at the beginning of each year they do a Biggest Breakthroughs, and you can play them one after another.

2026.01.22 1440’s page on its Science & Technology gives “informative overviews and expert-curated resources”. Here are just a few of the resources:-

- See every known species on this tree of life interactive

- Explore an interactive 3D model of the brain

- Explore an interactive map of the unified theories of everything

- Generative AI

- Quantum Mechanics

- Time

2026.01.16 1440 put together a great introduction to CRISPR, which is a molecular tool that can make precise changes to a gene’s DNA. An acronym for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats,” the tool was discovered in single-celled organisms, where it acts as an immune system to attack invasive viruses. Scientists have since used it to target and manipulate precise sections of DNA—the genetic blueprints for living things.

Each CRISPR has two parts—a “guide RNA” designed to latch onto a specific region of the DNA molecules and a Cas protein that cuts the targeted area (explore simulation). Cells try to repair the cut but often do so incorrectly, effectively deactivating that part of the blueprint (watch visualization). These deactivations can be used as medical treatments by selecting problematic genetic blueprints, such as those that cause an increased likelihood of getting cancer.

Dozens of clinical trials are underway for treatments that utilize CRISPR to address a range of diseases and allergies. Scientists are also utilizing CRISPR to develop new crops for food production, enhance the resilience of existing crops, and improve the sustainability of farming practices (learn more).

Also, check out …

- Scientists have crossbred heat-resistant corals using CRISPR. (Read)

- Astronauts have repaired DNA in space using CRISPR. (Read)

- How CRISPR can drive malaria mosquitoes to extinction. (Read)

- The wartime apparel made with CRISPR-modified bacteria. (View)

Explore everything else we’ve found on CRISPR.

2026.01.12 Quanta Magazine tells us Why Do Cells Need To Die?

It is a cold, dark January here in the Northern Hemisphere. What better time to talk about cell death? Alas, every cell that lives will one day die, but typical cell death isn’t disruptive, chaotic, or injurious. It’s part of life. In the early 1970s, researchers described a formal, highly controlled death process known as apoptosis. It is widespread across the tree of life and regulated by the same genes in a diverse range of species, from worms to mammals.

When a cell is stressed or receives a particular signal from a neighboring cell, it starts to deteriorate systematically and safely through apoptosis. The cell shrinks; its internal contents condense and then collapse. Finally, it breaks apart into tiny sacs, known as blebs, which can be taken up by surrounding cells that can reuse the molecular parts. Crucially, apoptosis doesn’t hurt the dying cell’s neighbours; in uncontrolled cell death processes, such as necrosis, a sick cell bursts open, releasing toxic compounds that can damage surrounding cells. By contrast, apoptosis is like a controlled demolition.

The ability of cells to die in this way is critical for the survival of multicellular species. In animals with nervous systems, for example, early development can be a violent time: A growing brain has many more cells than it needs and must shape and refine itself by killing off many of those neurons. When apoptosis goes awry, it can lead to a slew of complications. Cancer is composed of cells that should die but don’t, while people with autoimmune diseases are riddled with cells that should not die but do.

Though the process appears simple, questions of cellular life and death conceal great complexities. “The whole field of cell death is plagued by this question of defining what a dead cell is,” said the cell biologist Shai Shaham in a 2024 episode of our podcast The Joy of Why. Researchers are continuing to unpack what it means for a cell to live or die — and even to come back to life.

What’s New and Noteworthy

The origin of programmed cell death likely dates back billions of years, to ancient bacteria. In one study, researchers found that 2 million years ago, the first eukaryotes — a cell type with complex organization, including a nucleus and mitochondria, like those that make up our bodies — likely already had the tools for apoptosis, inherited from simpler bacterial forebears. It’s still debated why exactly the process originated. Some researchers speculate that ancient bacteria may have used these tools as defenses from external predators. Others propose that apoptosis evolved in single-celled organisms as a method of self-sacrifice for the good of the population, to prevent the spread of disease, for instance.

Cell death must be final, right? Turns out it’s not. Under the right conditions, some cells that have undergone apoptosis can resurrect themselves in a process called anastasis, after the Greek word for “rising to life.” This process both repairs cellular damage and restarts cellular processes. Just as apoptosis is a highly controlled process, so is anastasis; likewise, researchers have found anastasis in many different organisms, from fruit flies to rodents. It may have evolved as a way to hit the brakes on widespread apoptosis after severe but temporary stress, to limit permanent tissue damage.

Sometimes what may look like death is more like a really long nap. Most life on Earth is dormant: When faced with harsh conditions, like cold temperatures or a dearth of food, many species can slow down their metabolism and enter dormancy. But how? One study identified a protein, called a hibernation factor, that “pulls the emergency brake” in cells in Arctic permafrost by halting the creation of new proteins. Dormancy isn’t unique to microbes: In the human body, oocytes (egg cells) and immune system lymphocytes can stay dormant for long periods of time.

2026.01.11 1440 tell how to make sense of the Chernobyl disaster, which was the worst nuclear accident in history. During a late-night safety test on April 26, 1986, at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in present-day Ukraine, a combination of design flaws and operator errors triggered a massive power surge, leading to a pair of explosions that released radioactive material across large parts of the Northern Hemisphere.

The Soviet government initially downplayed the incident, waiting 36 hours to evacuate the nearby city of Pripyat, home to 50,000 people. An exclusion zone spanning 30 kilometers (19 miles) from the reactor was eventually established, displacing more than 300,000 people, while over 500,000 “liquidators” worked to decontaminate the site. A steel and concrete sarcophagus was then built in about seven months to contain the damaged reactor.

Chernobyl undermined trust in Soviet leadership and contributed to the USSR’s eventual collapse five years later. Its legacy includes not just environmental damage, but lasting physical and psychological harm for those affected and lasting uneasiness over nuclear power.

… Read our full explainer on Chernobyl here.

Also, check out …

- Unpack the chemistry behind the catastrophe at Chernobyl. (Watch)

- The “Elephant’s Foot” in Chernobyl is part of the largest documented mass of corium. (Read)

- See eerie footage of the abandoned city of Pripyat a year after the event. (Watch)

- Attempts to suppress information about Chernobyl led to conspiracy theories. (Read)

2025

2025.10.13 Dynamic line rating can soothe power-grid congestion

Introduces concepts such as Ampacity and Dynamic Line Rating

2025.10.07 UnMarker Undoes AI Image Identifiers

2025.10.03 How One AI Model Creates a Physical Intuition of Its Environment

Meta’s Video Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture (V-JEPA) begins to make sense of how the world physically works

2025.08.13 The AI Was Fed Sloppy Code. It Turned Into Something Evil.

Sloppy code (ref. sloppy Morse was produced by a “poor fist”) is often produced by vibe coders who end up producing just AI slop. But this article is about research into something more serious namely “emergent misalignment”.

2025.03.05 A New, Chemical View of Ecosystems

Also introduces the concept of KeyStone Species

2024

2024.10.24 Netscape’s birth and some thoughts about the web

2024.10.03 Google introduces new way to search by filming video

2024.07.06 The search for the random numbers that run our lives

2024.05.22 Shaping the Outlook for the Autonomy Economy

2024.04.16 The cloud under the sea

2024.04.13 Sweden has long opposed nuclear weapons – but it once tried to build them

2024.04.12 Poisoning Data to Protect It

Checkout Midjourney, Nightshade, AntiFake