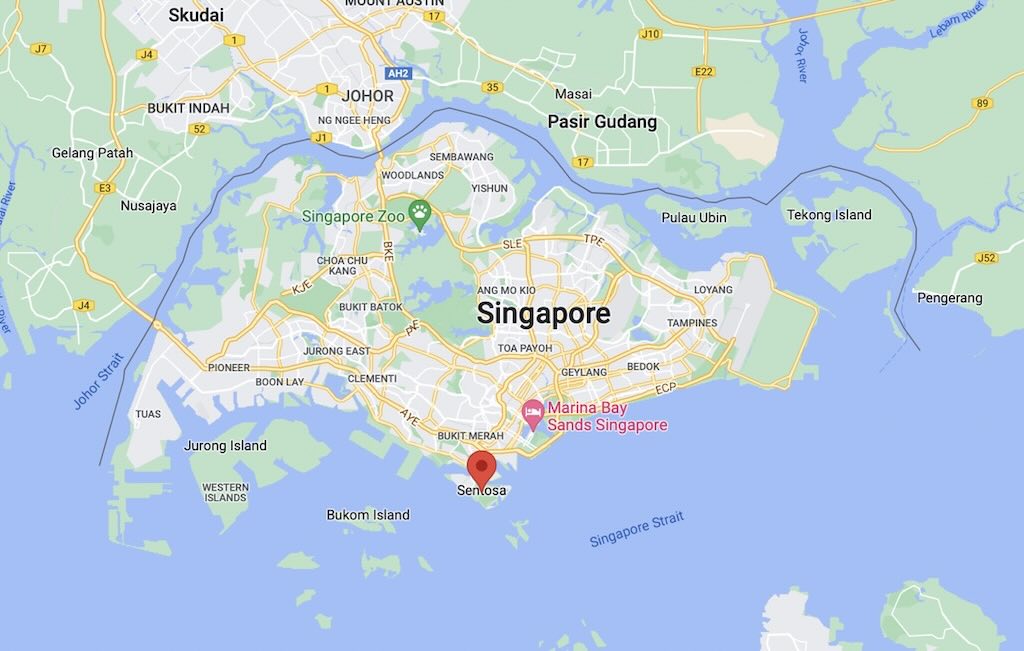

I had decided to follow an Oxford University Summer School (2026) on the subject “130 Years of Discovery: Nuclear and Particle Physics from Becquerel to Gianotti”.

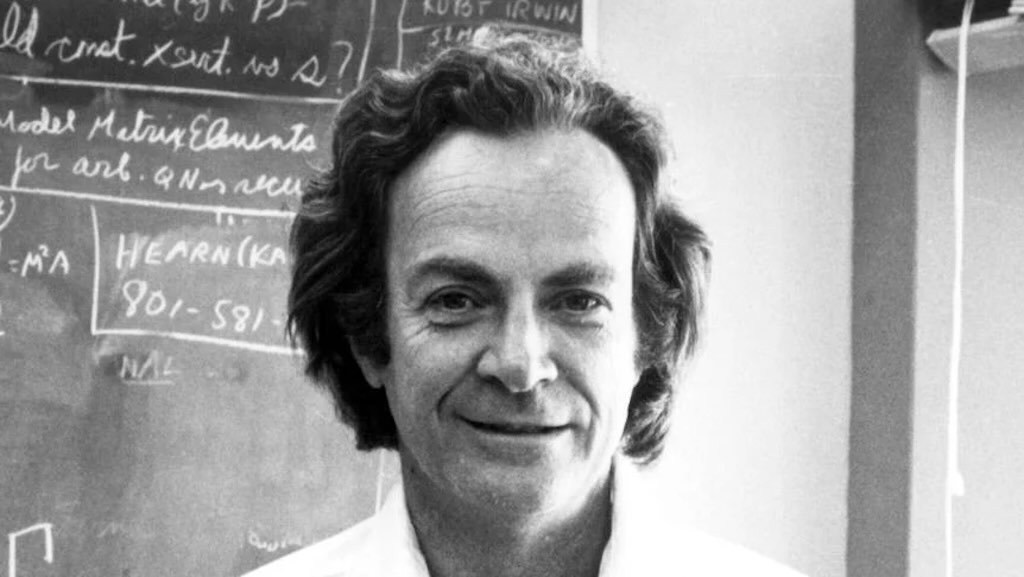

One of the recommended reading was Six Easy Pieces by Richard P. Feynman, and introduced by Paul Davies. This short book (146 pages) is subtitled “Essentials of Physics Explained by Its Most Brilliant Teacher“.

So this is less a book review and more a note taking, trying to capture the key messages.

Did I enjoy reading this book. I can’t say I did, but I did enjoy trying, in my own modest ways, to understand how Feynman approached both the science and teaching.

I did however, really enjoy challenging myself, after so many years gone by, to grasp (more or less), some the principles that are so fundamental to physics.

Introduction by Paul Davies

Davies start by considering Feynman a late 20th century icon, following in the footsteps of Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein. He mentions Feynman’s not inconsiderable scientific work, but highlights his ability to “approach essentially mainstream topics in an idiosyncratic way”. Frankly, the introduction is more appropriate to Feynman’s audio-video lectures and talks, and less well adapted to the contents of this little book.

This book is “culled” from Feynman’s Lectures on Physics. which are freely available on the Web. It draws on the early, non-technical chapters in his Lectures, so it’s a kind of primer on physics for non-scientists.

Davies stresses:-

All physics is rooted in the notion of scientific law, but they are not always transparent when we observe nature. Can we see (imagine) these laws and the way they describe order in the universe?.

The study of the solar system and the laws of planetary motion, yielded Newton’s inverse square law of gravitation. Then came other non-gravitational laws, describing how particles of matter interact with each other.

Here the role of symmetry and conservation laws brought order to a “zoo” of subatomic particles. One important, but apparently obvious statement, is that no matter when you make a measurement you see the same physical phenomenon, expressed as “invariant under time translations“.

Another law is that energy is conserved, in that you can move energy around and change its form, but you can’t create or destroy it.

The final section of this book looks at quantum physics, which is a very successful theory with multiple applications, but which does not appear to follow what we might call common sense. It is here that Davies sees Feynman making his most important contributions.

Atoms in Motion

The starting position was/is that physics is the most rapid developing field of knowledge over the past two hundred years. And that it was, and still is, essential to condense an enormous mass of results into a few laws that summarise all that knowledge. And then the challenge is to map the way those laws tie one specialist field of science to another field of science. Yet, accepting that these laws are an approximation to the complete truth about nature (or the truth as far as we know it). The test of all knowledge is experiment, and this helps Man guess what patterns explain the results seen.

Feynman starts with a simple experiment. Weigh something, and then spin it, and it weighs the same. Conclusion is that mass is constant. However, today we know that a mass travelling at near the speed of light increases. So today we begin to know what the true law is, even if for ordinary speeds our original idea is perfectly usable. However, we must accept that the original idea was completely wrong, and recognise that even a small effect can sometimes require a profound change in the way we see nature.

Interestingly, Feynman asks the question, which do you teach first? The correct but difficult to understand law, or the simple, but incorrect, “constant mass” law?

Feynman starts with the idea that everything is made up of little atoms, all in perpetual motion, attracted to each other when a little distance apart, but repel each other when squeezed together. Water looks nice and smooth, from a distance. Even with a very good optical microscope it looks like a droplet. Magnify again and we will see the surface moving around, and no longer smooth. Magnify that droplet a billion times and we will see no clear edge, but a series of blobs (atoms of oxygen) attached to two other blobs (atoms of hydrogen). They will appear attached (attracted to each other), but also we would see that the little groups don’t overlap, or they can’t be squeezed together.

We would also see that the these collections of atoms, called molecules, do not fall apart. They are clearly attracted to each other, and keep the same volume. We see this attraction working when our droplet rolls down a slope.

These molecules are in constant motion, and the faster the motion, means more heat, a temperature rise, and the volume starts to get bigger as the space between molecules gets bigger. As they move around even more, the molecules start to separate one from another, and we have steam. And these separate molecules will increasingly bounce against the walls of the container, trying to push the walls away, and averaged we would conclude that the gas is applying a pressure on the walls. If one of the walls could move (like a piston), we would conclude that we need to apply a pressure to keep the piston in the same place.

If we double the number of molecules in the same volume, we double the density, and keeping the temperature the same, we would see that the pressure is proportional to the density. It’s a decent approximation, because we have actually reduced the empty volume by adding molecules, and being pushed closer together they will start to attract each other, and will also occupy a bit less space.

If we increase the temperature, and keep the density the same, the molecules will move faster, and more often hit the walls. So pressure increases. Let’s push the piston down, the volume decreases, and the atoms/molecules are slowly compressed together. They will pick up speed from those collisions with the piston, so they get “hotter”.

So, under a slow compression, a gas will increase in temperature, and under a slow expansion, the temperature will decrease.

Let’s now decrease the temperature, the molecules will move arounds less rapidly, and those attractive forces will start again to play a role. Drop the temperature further and the atoms in the molecules will start to take up their original places. They start to create a crystalline array, as the molecules start to compress into solid ice. Because the hydrogen atoms are attached to the oxygen atom at about 120°, when compressed they form naturally a hexagonal symmetry (this is why snowflakes have six sides). We also see that a hexagonal has a kind of space, or hole, in the middle, and this is why ice shrinks as it melts (that hole will gradually disappear). Even if we reduce the temperature to an extreme, the atoms and molecules will always have a residual energy. For example, with Helium we can reduce the temperature (down to absolute zero), but we can’t create Helium ice (freezing). To do that we would also need to increase the pressure, to make Helium become solid.

Using Feynman’s introduction, we can describe the different physical states of our simple molecule, in terms of atomic processes.

PHASE CHANGES (State Transitions)

Gas-phase H₂O consists of widely separated molecules with negligible hydrogen bonding compared with liquid water. The molecules have broken free and move independently like an invisible cloud.

Surface molecules with kinetic energy exceeding intermolecular binding escape into the vapour phase below the boiling point. Only the fastest molecules are able escape (“get away”) from the surface.

Boiling (bubble formation)

Vapour bubbles form when the liquid’s vapour pressure equals external pressure, allowing gas pockets throughout the volume. Now the liquid starts turning to a gas everywhere, not just at the top.

Gas molecules lose kinetic energy and are captured by intermolecular attractions, forming a liquid phase. The molecules slow down and begin sticking together again.

Thermal energy disrupts the crystalline lattice so molecules can move past one another while remaining in close contact. The solid’s rigid structure collapses into fluid motion.

Molecular motion decreases until intermolecular forces lock particles into an ordered lattice. The molecules settle into fixed positions like a snapped grid.

Molecules leave a solid directly into the gas phase when surface binding energies are overcome without a liquid intermediate. The solid “vanishes” molecule by molecule into air.

Gas molecules lose energy and attach directly into a solid lattice, releasing latent heat. So the vapour crystallises straight onto a surface.

MIXING, DISSOLVING AND TRANSPORT

Dissolving (solids in liquids)

Solvation occurs when solvent–solute interactions offset lattice energy, allowing ions or molecules to disperse in solution. The solvent pulls particles out of the solid and carries them away.

Random thermal motion produces net transport down a concentration gradient, described statistically by Fick’s laws. The molecules spread out simply because they are always moving around.

Solvent flows across a selectively permeable membrane toward higher solute concentration to equalise chemical potential. The water moves to dilute the more “crowded” side.

Cohesive intermolecular forces create an energetic penalty for increasing surface area, producing a contractive surface stress. The surface behaves like a stretched film because molecules are pulled inward.

Internal friction arises from momentum transfer between molecular layers during flow. So thicker liquids resist motion because molecules hinder each other’s movement.

SOLIDS, STRUCTURE, AND MECHANICAL CHANGE

Particles arrange into a periodic lattice as the system minimises free energy through ordered bonding. The molecules “choose” the most stable repeating pattern.

Rapid cooling prevents crystallization, freezing molecules into an amorphous metastable solid state. The liquid becomes solid before it can organise properly.

Atomic bonds stretch reversibly under applied stress, storing energy as potential energy in bond distortion. Atoms behave like tiny springs that return when released.

Permanent shape change occurs through dislocation motion and irreversible rearrangement of atomic planes. Layers of atoms slip over each other, and do not return.

Bond rupture propagates when stress intensity exceeds the material’s cohesive strength.

Cracks spread when bonds fail faster than forces can redistribute.

CHEMICAL TRANSFORMATION

Reactions involve electron redistribution, with bonds broken and formed as the system moves between quantum energy states. Atoms reshuffle their bonds by rearranging electrons.

Proton transfer alters bonding and charge distribution, governed by equilibrium constants and solvent stabilisation. One molecule gives an H⁺ to another.

Electrochemical oxidation converts metal atoms into ions, producing oxide compounds through redox reactions. The metal is slowly eaten away by oxygen and water.

Monomers form covalently bonded chains via reaction pathways that propagate through reactive intermediates. Small units link into long molecular strings.

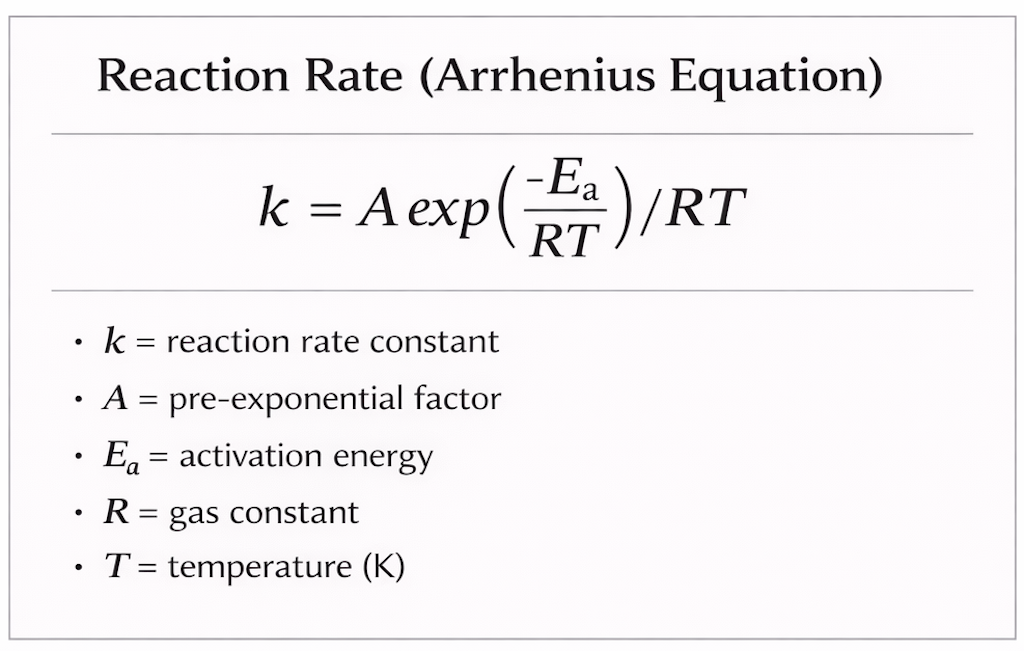

Catalysts lower activation energy by providing alternative reaction mechanisms without being consumed. They make reactions easier without being used up.

COMBUSTION AND OXIDATION PRODUCTS

Combustion is a rapid exothermic redox reaction where fuel is oxidized by O₂, releasing heat. Chemical energy is dumped out quickly as fire.

Incomplete oxidation yields CO when oxygen supply or mixing is insufficient for full conversion to CO₂. Carbon only half-finishes its reaction with oxygen.

Complete oxidation produces CO₂ as the thermodynamically stable endpoint of carbon–oxygen bonding. Carbon fully “burns through” into its most stable form.

Incomplete combustion generates aerosols of carbonaceous nanoparticles and unreacted hydrocarbons. Tiny solid fragments and gases escape instead of clean burning.

LIGHT AND RADIATION FROM MATTER

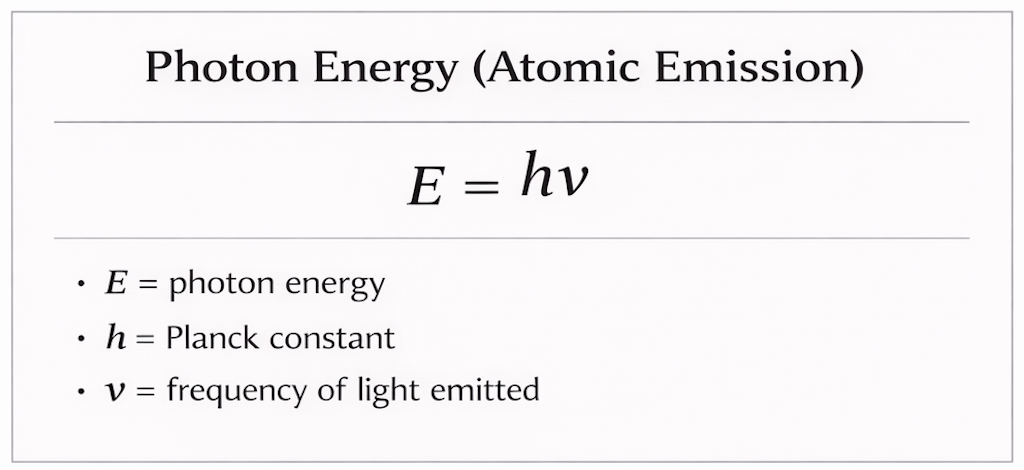

Electronic excitations in hot gases relax via photon emission at characteristic energies. Heated atoms glow because electrons drop to lower energy levels.

Thermal radiation arises from blackbody-like emission as charged particles accelerate in hot matter. Anything hot enough shines.

Absorbed photons excite electrons, which decay rapidly to emit lower-energy photons. Energy immediately produces light.

Electrons become trapped in metastable states, delaying photon emission.

The material keeps glowing after the light is removed.

ELECTRICITY AND CHARGE EFFECTS

Charge carriers drift under an electric field, scattering from lattice vibrations and impurities. Electrons flow but constantly bump into atoms, producing resistance.

Charge imbalance persists on insulating surfaces until discharge occurs through breakdown of air or contact. Extra electrons build up until they suddenly jump.

ATMOSPHERE AND SUSPENSIONS

Supersaturated vapour condenses onto nucleation sites, forming suspended microdroplets. Invisible vapour turns into visible droplets around dust.

Condensation near the ground produces dense droplet suspensions when air cools below its dew point. A low level cloud forms.

Small particles remain suspended due to Brownian motion and low gravitational settling velocity. Tiny droplets float because they are too small to fall quickly.

EXTREME RAPID EVENTS

Local pressure drops below vapour pressure, forming voids that collapse violently when pressure recovers.

Bubbles form and implode like microscopic hammer blows.

A rapid exothermic reaction produces gas expansion faster than pressure can equilibrate, generating a shock wave.

Eenergy is released so fast the air itself is slammed outward.

For the mathematically minded

It expresses how the rate of a chemical reaction increases with temperature because only molecules with enough energy to overcome the activation barrier can react.

When an atom or molecule is heated or excited, its electrons can jump to higher energy levels. When they fall back to a lower level, the lost energy is released as a photon of light, meaning higher-frequency light corresponds to a larger energy drop.

What is Feynman is trying to teach us about Atoms in Motion?

It’s all about experiments, and what can be deduced as principles and natural laws.

Firstly, all macroscopic materials consist of discrete, countable microscopic entities (atoms/molecules) exhibiting persistent identity and localisation, with motional degrees of freedom. And this means reproducibility of gas laws, Brownian motion, diffusion rates, heat conduction, viscosity, and chemical stoichiometry (based on the law of conservation of mass).

The atomic number (the number of protons found in the nucleus) defines the identity of each chemical element. And the bound electron configuration determines chemical bonding and spectroscopy.

The diameter of the nucleus is five orders of magnitude smaller than the diameter of the atom itself (nucleus + electron cloud), implying mass is concentrated.

The atom with its nucleus and electron cloud is in constant motion, even very close to 0 Kelvin. This continuous motion is a universal physical property. It has its origins with kinetic energy from random thermal movement at non-zero temperature. An atom or molecule can move in three independent directions (so translation has three degrees of freedom), and interatomic collisions redistribute momentum, maintain ergodicity, and defines transport phenomena (diffusion, viscosity, thermal conduction). Also atoms are not static lattice points, and persistent thermal agitation is intrinsic even in solids. So this constant motion spans translation (i.e. the straight-line motion of the centre of mass of atoms and molecules in gases and liquids), vibration (in solids), rotation (spinning about its centre of mass in gases and liquids), and internal electronic motion (the internal energy associated with electrons occupying molecular or atomic electronic states, and transitions between these states).

Historically, temperature was defined macroscopically (thermometers, gas laws), and energy was defined mechanically (work done). Boltzmann showed that to connect them microscopically you needed the Boltzmann constant (kB), a proportionality factor that relates the average relative thermal energy of particles in a gas with the thermodynamic temperature of the gas.

At T ≈ 300 K, kB = 8.617×10−5 eV/K

Molecules at 300 K are constantly moving due to thermal agitation, and the typical kinetic energy scale of that motion is about ~10−2 eV, or a few tens of milli-electron-volts. This compares to electronic excitation energies for a few ~eV, and nuclear energies in MeV.

In gases there is translational freedom with free center-of-mass motion, and movement is collision-dominated characterised by a collision frequency. In liquids motion is still translational, but diffusion is slower than in gases (and characterised by a self-diffusion coefficient). In solids, atoms oscillate around equilibrium positions in a lattice.

For Feynman, Brownian motion constituted a visually accessible “macroscopic amplifier” of atomic agitation.

He always wanted to talk about microscopic motion that would lead to macroscopic laws. Conduction emerges from microscopic energy exchange via collisions/phonons. Momentum transport as seen in viscosity, emerges from microscopic momentum transfer. Mass transport is seen in how diffusion emerges from the random walk of particles. Electrons are bound via Coulomb attraction to nucleus, and electronic motion is seen in measurable spectral lines and verifiable chemical bonding.

He also always wanted to see experimental confirmation. For example, in certain types of spectroscopy (e.g. high-resolution atomic spectroscopy on low pressure gas), one can see that lines are broader due to the Doppler effect on the velocity distributions, and this is consistent with Maxwell–Boltzmann. In X-ray crystallography there is direct spatial confirmation of atomic lattice spacing, and thermal motion predicted by Debye–Waller. Raman spectroscopy determines vibrational modes of molecules. Studies of quantum liquids (e.g., He-4) show an absence of classical freezing, meaning that there is persistent atomic motion due to zero-point energy.

A little example of "Atoms in Motion" from my past

Mixer–Settler (PUREX) is “Atoms in Motion” applied to nuclear fuel reprocessing.

A mixer–settler is a staged liquid–liquid extraction unit used in spent-fuel reprocessing to separate and purify uranium and plutonium from highly radioactive fission products. The purpose is to recover usable nuclear material and reduce the waste stream by controlled molecular partitioning.

Stage-wise liquid–liquid extraction using mixer–settler concepts was developed in early 20th-century chemical engineering and became widely used in hydrometallurgy before PUREX applied it at industrial scale after World War II.

In practice, many mixer–settler stages are connected in series, because each stage performs only a partial separation, and repeated stages produce higher purity.

First, molecules are brought into contact

In the mixer, an aqueous nitric-acid solution containing dissolved fuel ions is vigorously contacted with an immiscible organic solvent (typically TBP (tributyl phosphate) in kerosene or dodecane). Random thermal motion drives transport across the interface, and it is this movement that enables the solute species to reach the organic phase.

Second, selective chemical complexation

U and Pu form solvated complexes with TBP that are more stable in the organic phase than in water. Their distribution is governed by equilibrium chemistry and the TBP molecules surround the uranium complex and carry it into the organic liquid.

Thirdly, settling involves the clean separation

In the settler, agitation stops and the two immiscible liquids separate under gravity, with surface tension restoring a sharp boundary. So the liquids “unmix” because molecular cohesion favours distinct phases.

Each stage transfers a fraction of uranium/plutonium into the organic stream while leaving most fission products behind in the aqueous stream. A cascade of mixer–settlers therefore acts as a stepwise molecular sorting system, producing progressively cleaner separation. As such a mixer–settler is a practical machine built from “Atoms in Motion”. Diffusion brings molecules together, equilibrium decides where they belong, and phase separation completes the sorting, repeated across many stages for purification.

Feynman's Basic Physics

Feynman next looks at what he calls “basic physics”. This is not “basic” in the sense of simple. His “basic physics” is really “fundamental physics”. It is not, let’s take what Newton wrote, plug in some numbers, and check that it works (for all practical purposes).

Feynman’s basic physics is about the basic structure of matter, the basic logic of forces, and what somehow does not work (where the “rules of the game” don’t work). We use scientific method, acquiring knowledge through careful observation, rigorous skepticism, hypothesis testing, and experimental validation (he calls it observation, reason and experiment).

Feynman suggests that we start with a guess (a rule) based upon observing some simple natural process. Then we see if other less specific rules derive from that first rule. We may discover some new rules, and we can start to identify where those rules don’t work. Third, is about how well some relatively crude approximations still work. This allowed Man to classify what was heat, electricity, mechanics, magnetism, physical and chemical properties, light (then optics), x-rays, nuclear, gravitation, and so on. The real challenge was (is) to find the laws behind the experiments, to bring all these classes together.

Feynman looked at the year 1920, with space as three-dimensional, time to define change, particles with their properties, forces such as inertia and gravity. But what kept the particles together in those 92 elements? It’s not gravity, since it’s both far too weak, and it has to deal with things having a different charge, e.g. attraction and repulsion. Models of the atom were being suggested, with a positively-charged nucleus and very light, negatively charged orbital electrons.

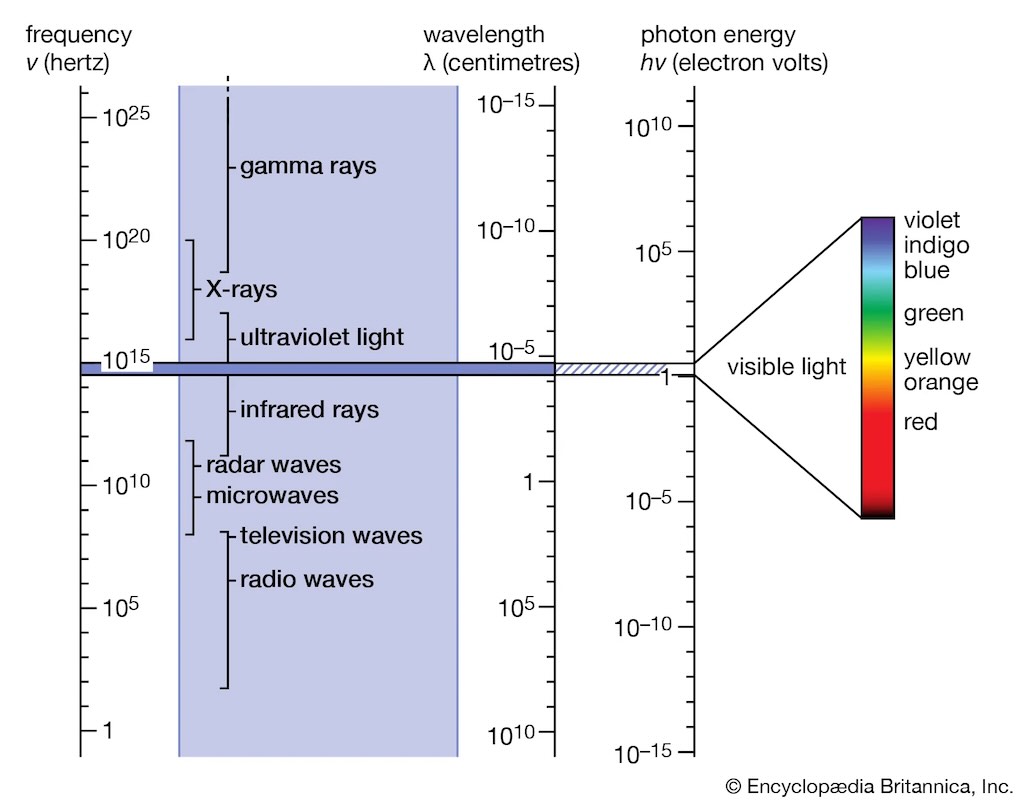

It is here that we start to see the Feynman touch. He introduces a charged comb, near a piece of paper. Move the comb, moves the paper so it always points to the comb. Shake the comb, we see that the paper moves, but with a little delay. Move the comb further aways from the paper, and the delay gets bigger. Shake the comb, and the inverse-square law does not appear to work, the influence on the paper extends much further out (the influence falls off more slowly than the inverse-square). What we have are a complex set of effects. It’s not just charges attracting in an electric field, but the charges are in relative motion, and we are seeing two different aspects of the same thing, a changing electric field can’t exist without magnetism. So the idea of electrical interaction has to replaced with what is called an electromagnetic field. It is this field that is characterised by the frequency of oscillation. A few hundred oscillations per second is just an electrical disturbance, more becomes radio, radar, then light, and then X-rays, gamma-rays, and cosmic-rays, and we have the whole electromagnetic spectrum.

Living the 21st century, we have come to understand that the moment we think we understand something, we discover we don’t. Having established that there is an electromagnetic field that carries waves, we find that the waves don’t always appear to behave as waves. You have guessed it, at higher frequencies the waves appear to behave more like particles. It’s all about quantum mechanics.

Einstein had introduced space-time, and had then curved it to represent gravitation. And this meant that the rules for the motion of particles wasn’t quite right. Newton’s idea about inertia and forces were wrong in the world of atoms. And worse, the new rules don’t appear intuitive.

Firstly, particles can’t have a defined location and a defined speed. Or more precisely, we can not know where something is and at the same time know how fast it is going. This means we can detect a photon, but we can’t say when the atom would emit the photon, or even which atom would emit it. As we see it today, this is not because we don’t sufficiently well understand nature, it’s because it is fundamentally impossible. Surely if you set things up in the same way, you should get the same result? No. We can only find statistical averages. Is this bad? Maybe not, since we must focus on the experiments, and if they are occasionally different, we will have to find a way to live with the consequences.

There are some advantages, for example, quantum mechanics has unified the idea of fields and its waves, with particles. At low frequencies waves are a decent description, and at higher frequencies particles are a better description.

In the above diagram we see frequencies of gamma-rays or cosmic-rays, but these are “equivalent frequency”. The highest frequency actually measured is only in the hundreds of terahertz, in the field of optical frequency metrology.

So in addition to the electron, proton and neutron, there is the photon. And understanding the interaction of a proton (matter, or charges) with a photon (light, or electric field), became known as quantum electrodynamics (the relativistic quantum field theory of electrodynamics). It’s Feynman’s pet topic, and he tells us that “in one theory we have the basic rules for all ordinary phenomena, except for gravitation and nuclear processes. Out of quantum electrodynamics comes all of the know electrical, mechanical and chemical laws, the laws for the collision of billiard balls, the motion of wires in magnetic fields, the specific heat of carbon monoxide, the colour of neon signs, the density of salt, and the reactions of hydrogen and oxygen to make water, are all the consequences of this one law”.

Quantum electrodynamics is the theory of all chemistry, and of life. If life can be reduced to chemistry, which can be then be reduced to just physics.

It also predicted the existence of the positron, which was later generalised that every particle had its antiparticle.

The next question was, what are nuclei made of? And how are they help together? This led to the pion, which would provide an explanation for the residual strong force between nucleons.

Here we start to hit the limit of the book, first written in 1963. How do all the particles being discovered fit together? He want a Mendeléev-type chart for the new particles.

First came the Fermion (1926–1927), as a general quantum-statistics concept, not a particle category. But with quantum mechanics, particles were divided by their spin and statistics. Fermi–Dirac was for particles with half-integer spin (spin 1/2, spin 3/2, etc.), and “Fermion” means particle obeying Fermi statistics. And there was Bose–Einstein for particles (called the Boson), whose spin quantum number has an integer value (0, 1, 2, …). This was about trying to explain atomic structure and the Pauli exclusion principle.

Then came the Lepton (late 1940s). Electrons were known since 1897, the muon discovered 1936, and the neutrino was proposed 1930, and detected later. These particles do not feel the strong force, and are “simple” and point-like. The name says it all, from Greek leptos = “light, small, fine”. The reason was to separate light, weakly interacting particles from strongly interacting ones.

The Baryon (1950s) were identified as the “heavy nucleon-like” hadrons. The proton and neutron were known, and other heavy relatives found later (Λ, Σ, Ξ…). The name is from Greek barys = “heavy”. The idea was to distinguish heavy strongly interacting particles (proton-like) from lighter mesons. Later baryons would be particles that contain 3 quarks.

Finally the Hadron (early 1960s) appeared when the zoo of strong-interaction particle exploded. By the 1950s, many new strongly interacting particles were found (pions, kaons, hyperons…). A collective term was needed for “particles that participate in the strong interaction”, and the Greek hadros means “thick, heavy, strong”. Today Hadrons include Baryons and Mesons.

And there was (is) the Graviton, the hypothetical elementary particle that mediates the force of gravitational interaction.

So lots of particles, but possibly only four different types of interaction (in decreasing strength).

Nuclear force, that acts between hadrons, most commonly observed between protons and neutrons of atoms.

Electrical interaction, an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields.

Beta-decay interaction, a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron).

Gravity, a fundamental interaction, which may be described as the force that draws material objects towards each other.

Feynman concluded that (at that time), quantum mechanics works, but we didn’t know how the universe started. We didn’t know if space-time was accurately over all distances, since there is was no experimental validation yet. We didn’t yet know the world of sub-atomic particles, and we didn’t know how all the particles discovered interact.

The Relation of Physics to Other Sciences

Feynman wrote (in the 1960s) that:-

Mathematics is not a science, in the sense that it is not a natural science.

Theoretical chemistry is just physics, because it’s explained by quantum mechanics. But is is still very difficult to predict what will happen in a given chemical reaction. Inorganic chemistry is just physical chemistry and quantum chemistry. Organic chemistry is different and difficult, in particular in the analysis and synthesis of substances which form living systems. But things are moving towards biochemistry and molecular biology.

Biology involves many different physical phenomena (e.g. circulation, pumps, pressure, ions, electrical signals, etc.). But is a very wide field and we still don’t even know how things like vision works. I have not included here Feynman’s discussion of biology, but he does conclude that all things, including living things, are made up of atoms.

Astronomy has shown today (I guess the 1960s) that stars are made up of the same atoms as found on Earth. We know what makes stars burn, it’s the nuclear “burning” of hydrogen to make helium.

Meteorology is far from perfect. It can’t describe well what today is like, and tell us what tomorrow will be like. Geology has still to answer why the Earth is the way it is.

Psychology is not a science, at best it is a medical process.

Conservation of Energy

I have to say I was (am), unimpressed by Feynman’s chapter of the Conservation of Energy.

He appears to avoid thinking of energy as a measurable physical substance. He appears to think of it as an abstract conserved quantity, something defined by the fact that it stays constant. More a bookkeeping device, a number which doesn’t change.

That is mathematically true, but physically unsatisfying. Maybe he overcorrected into abstraction.

What Feynman does say is:-

- There is no known exception to the law of conservation of energy.

- It’s a mathematical principle, that it does not change when something happens.

- It doesn’t describe anything concrete, it’s just that you calculate a number, then watch nature go through its “tricks”, and calculate the number again, and it’s the same.

- It’s important to calculate all the different forms of energy that leave and enter a system. And there are many different forms of energy, each with its own formula.

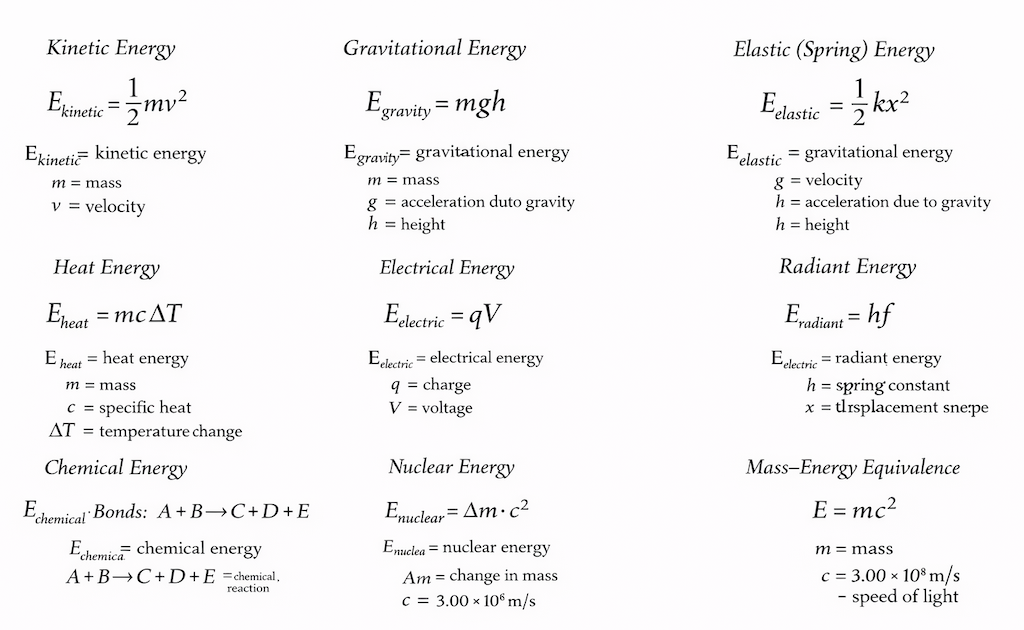

- He lists gravitational energy, kinetic energy, heat energy, elastic energy, electrical energy, chemical energy, radiant energy, nuclear energy (binding & potential) and mass energy. So he covered motion (kinetic), position in a field (gravitational), microscopic disorder (heat), deformation (elastic), electromagnetic interactions (electrical, radiant), chemical binding, nuclear binding, and rest mass. He doesn’t explicitly name magnetic field energy, rotational kinetic energy, surface tension energy, sound energy, latent energy, zero-point energy, vacuum energy, and dark energy.

- In physics today (1960s) we have no knowledge of what energy is. It is an abstract thing in that it does not tell us the mechanism or the reason for the various formula.

Let’s not dwell on whose fault it is, Feynman’s for failing to explain things, or mine, in failing to understand what he is saying.

There is a video called Energy – An Enigma which does a good job in overcoming my inability to follow Feynman’s logic.

Here is a podcast Conservation of Energy Explained | Chapter 4 – Feynman Lectures on Physics (Vol.1), which focusses on the exact content in Feynman’s lecture.

And here is a video of Feynman himself talking about electricity, Richard Feynman Explains The Big Misconception About ELECTRICITY.

You can also listen to Feynman talking about Conservation of Energy on the Feynman Lectures Playlist.

Ma favourite video is Doc of the Day: Excavating the Universe’s Energy Foundation.

And if you liked this video, perhaps you will also like Atom: The Key To The Cosmos (Jim Al-Khalili) | Science Documentary | Reel Truth Science.

Am I now better informed? Yes, but have I gone beyond Feynman’s description? Not sure, so work in progress…

For the mathematically minded

The Theory of Gravitation

Feynman adopts the word “gravitation”, the scientific theory describing gravity (as did Newton in his law of universal gravitation).

Feynman rightly saw the law of gravitation as one of the most important intellectual achievements of Man, and he also lauded how nature had adopted such an elegant and complete law to describe itself.

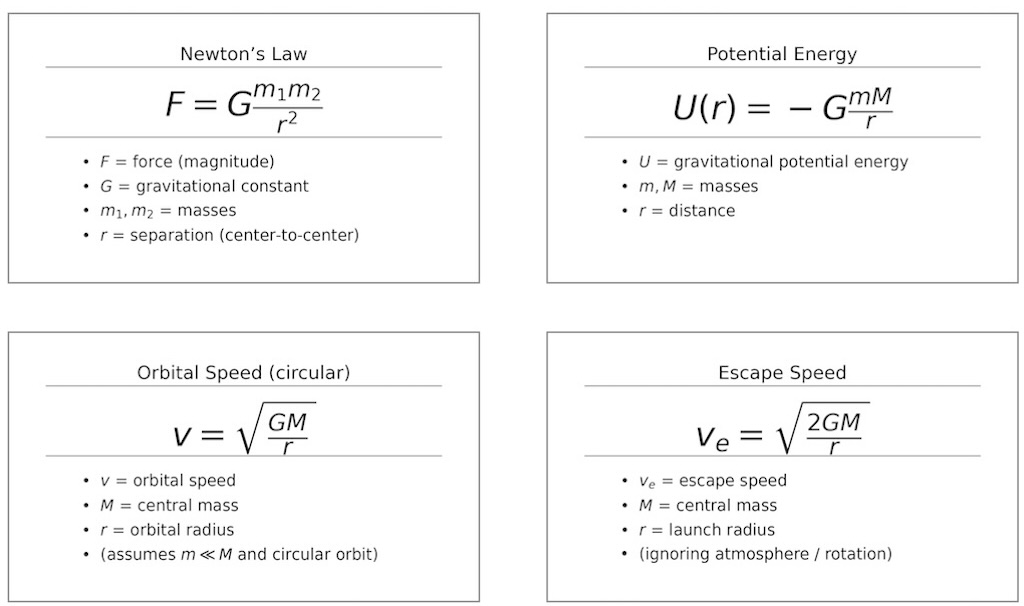

Every object in the universe attracts every other object in the universe with a force that is proportion to each mass and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

And the two masses respond to this force by accelerating in the direction of the force, by an amount that is inversely proportional to their mass.

Tycho Brahe was an astronomer of the pre-telescope era. Using just his naked eye, he observed the planets, Moon, stars, and space and recorded everything he saw while completing a multitude of calculations daily. His observations and calculations allowed him to develop more accurate Solar System models. He compiled the most extensive and accurate catalog of stellar positions up to that time. This laid the groundwork for astronomers in the future.

It was Johannes Kepler who introduced the revolutionary concept of a planetary orbit, a path of a planet in space resulting from the action of physical causes, distinct from previously held notion of planetary orb (a spherical shell to which planet was attached). The based on measurements of the aphelion and perihelion of the Earth and Mars, he created a formula in which a planet’s rate of motion is inversely proportional to its distance from the Sun. Verifying this relationship throughout the orbital cycle required very extensive calculation. To simplify this task, by late 1602 Kepler reformulated the proportion in terms of geometry, that is planets sweep out equal areas in equal times, which became his second law of planetary motion. He then set about calculating the entire orbit of Mars, and in late 1604 he at last hit upon the idea of an ellipse. Kepler immediately concluded that all planets move in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus, and this became his first law of planetary motion. Later Kepler would develop his third law describing relationship between the distance of planets from the Sun, and their orbital periods.

Feynman starts with Kepler’s laws, and turns to Galileo, who was interested in what made the planets go around in the first place. I’m not sure Galileo was convinced by the idea that planets were orbiting because they were pushed by invisible angels with wings.

Galileo started by concluded that objects retain their velocity in the absence of any impediments to their motion, thereby contradicting the generally accepted Aristotelian hypothesis that a body could only remain in motion if pushed by some agent of change. Galileo defined inertia as “any particle projected along a horizontal plane without friction will move along this same plane with a motion which is uniform and perpetual”. He also put forward the basic principle of relativity, that the laws of physics are the same in any system that is moving at a constant speed in a straight line, regardless of its particular speed or direction. This principle provided the basic framework for Newton’s laws of motion and is central to Einstein’s special theory of relativity.

However, Newton would also see that a force is needed to change the speed or direction of the motion, such as an orbiting planet. For planetary motion, if this force did not exist, inertia would simply mean that the planet would go off (from its orbit) in a straight line. The force needed to keep a planet orbiting the Sun was not a force around the Sun, but a force towards the Sun.

In 1687 Newton published his Principia which combined his laws of motion with new mathematical analysis to explain Kepler’s empirical results. His explanation was in the form of a law of universal gravitation. Any two bodies are attracted by a force proportional to their mass and inversely proportional to their separation squared. Taking on board Kepler’s third law it was possible to show that farther away the planet, the weaker the force. Perhaps Newton’s greatest achievement, was to conclude from the movement of planets around the Sun, that gravity was a universal force, that everything pulled on everything else.

Here we see again Feynman’s unique way to look at things, when he writes about the Moon always falling towards Earth. The question was about whether the “pull” of the Earth on people was the same as its “pull” on the Moon. If on the Earth’s surface, an object, released from rest, falls 16 feet in the first second, what happens to the Moon? In principle if there was no attractive force, the Moon should simple continue in a straight line, whereas it actually goes around on its orbit. So in some sense it constantly “falls in” towards the Earth. Considering the radius of the Moons orbit, and the duration of its orbit, how much does it “fall in” in one second? It’s roughly 1/20th of an inch. Comparing this with the object that is on the Earth’s surface (radius 4,000 miles), one would predict the Moon to “fall” in one second, roughly 1/200th of that 16 feet, or roughly 1/20th of an inch.

Newton actually performed that calculation, but using the wrong size of the Earth, the result was wrong. Six years later, with a new measurement of the Earth’s radius, he was able to confirm that 1/20th of an inch. And as a reminder, an object, on the Earth’s surface, shot out horizontally, will still fall that same 16 feet in that first second. And this is almost independent of the speed at which the object is projected. Almost, because at a very fast speed the curvature of the Earth’s surface starts to play a role. In fact, an object fired at a speed of 5 miles per second, will continue to “fall” towards the Earth’s surface, but will never get any closer to the Earth’s surface, because the Earth keeps curving away from it.

Newton used Kepler’s second and third laws to deduce his law of gravitation. Feynman goes on to write about tides, the roundness (slightly elliptical) of the Earth, the movement of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, the attraction between double stars, and even the attraction between objects throughout the an entire galaxy.

Feynman also wrote about Cavendish’s experiment, which was the first experiment to measure the force of gravity between masses in the laboratory and the first to yield accurate values for the gravitational constant.

The next question, was what makes planets orbits suns, etc. Not what the planets did, but why? Like conservation of energy, the laws describe how to calculate things, but do not explain why (Feynman calls this the machinery). Explanations abound, but they all involve some new consequences that turn out to be not true. Why do different laws, gravitation and electricity, both follow an inverse-square rule? Why is the ratio of electric repulsion to gravitational attraction, independent of distance, and appears to be a fundamental constant of nature (with lots of zeros)?

The last topic Feynman mentions in this section, is about gravity and relativity. Gravity was postulated as instantaneous, but “it” can’t go faster than the speed of light. According to Einstein anything that has energy, has mass, and must attract gravitationally. So light (energy) will be bent when going past the Sun. Despite the appearance of numerous new particles, and numerous new forms of interaction, none explain gravitation.

For the mathematically minded

Quantum Behavior

The sixth and last chapter is said to be the most challenging. The previous chapters were “classical”, and did not (yet) mention that light energy comes in “lumps” or photons.

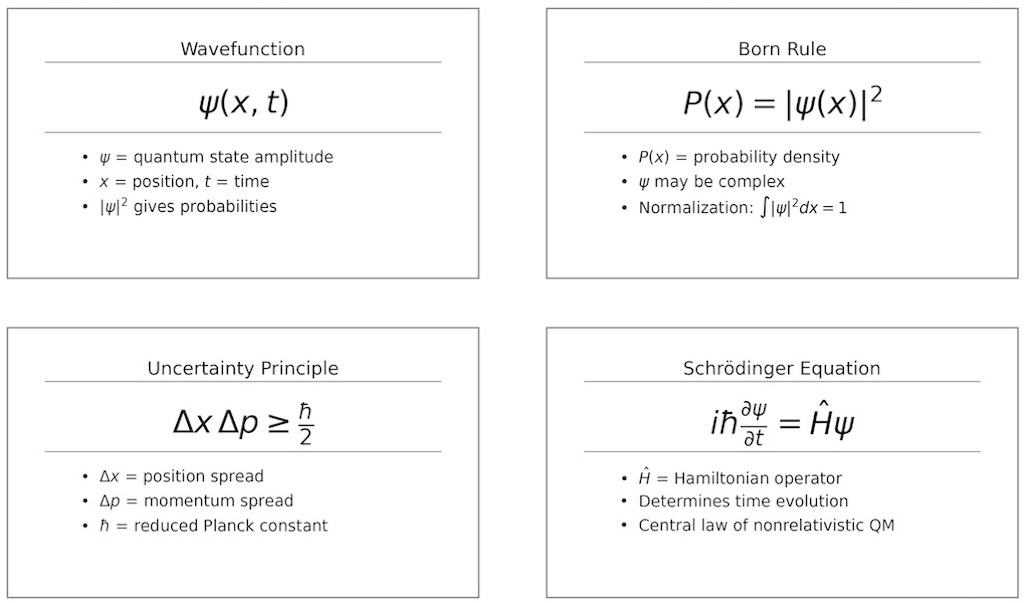

Feynman defines quantum mechanics as a theory that describes the behaviour of matter at and below the scale of atoms. The challenge was (perhaps still is) to describe things not as either particles or waves, depending upon the circumstances, but to have just one way to describe atoms and their small-scale behaviour.

Feynman starts by “setting the scene”:-

- Things on a very small scale behave like nothing that you have any direct experience about.

- They do behave like waves, they do not behave like particles, they do not behave like clouds, or billiard balls, or weights on a spring, or like anything that you have ever seen.

- The quantum behaviour of atomic objects (electrons, protons, neutrons, photons, and so on) is the same for all; they are all “particle waves”, or whatever you want to call them.

After noting that it was Schrödinger, Heisenberg and Born who finally “obtained a consistent description of the behaviour of matter on a small scale”, Feynman decided to look at something that can (absolutely) not be explained in a classical way.

I found Feynman’s description of the so-called “double slit” experiment difficult to read and understand. Frankly, I’m not sure there is a perfect description (easily understandable, intuitively simple, etc.), so I’ve listed a few links, in the hope that one of them “clicks”:-

Richard Feynman on Electron 2 Slit Experiment (original video)

Quantum mechanics and the double-slit (video) and The super bizarre quantum eraser experiment (video)

Double Trouble: The Quantum Two-Slit Experiment (1)

The double-slit experiment and The double-slits with single atoms

The double-slit experiment: Is light a wave or a particle?

Quantum double-double-slit experiment with momentum entangled photons

Feynman concludes:-

- We do not know how to predict what would happen in a given circumstance, and we believe now that it is impossible, that the only thing that can be predicted in the probability of different events.

- One cannot design equipment in any way to determine which of two alternatives is taken, without, at some time, destroying the pattern of interference.

- The uncertainty principle “protects” quantum mechanics.

For the mathematically minded

Practical Applications of Quantum Mechanics

If you do a better job than me, in understanding quantum mechanics, then it might be useful to go beyond Feynman and look at how it has impacted our everyday life.

I ask for your indulgence, but these practical advances come to mind.

In fact Wikipedia lists Applications of Quantum Mechanics, and it mentions the transistor, semiconductors, the microprocessor and integrated circuits, the optical amplifier and lasers, superconducting magnets, light-emitting diodes, the optical amplifier and the laser, medical and research imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging and electron microscopy. And of course, the more obvious quantum chemistry, quantum optics (more than just lasers), and quantum computing.

A few pointer for further reading:-

- Semiconductors rely on quantum physics to explain the movement of charge carriers in a crystal lattice. In fact developments in quantum physics led in turn to the invention of the transistor in 1947 and the integrated circuit in 1958.

- Diodes (p–n junctions) depend on the quantum band structure of semiconductors and the formation of a depletion region. Current flow is governed by quantum carrier populations across an energy barrier.

- LEDs emit light when electrons drop across a semiconductor band gap, releasing photons. Photon emission is governed by quantised electronic transitions.

- Lasers require stimulated emission, where an incoming photon induces an excited atom to emit a coherent photon. This is a purely quantum process based on (“excited“) quantum states.

- MRI relies on quantised nuclear spin states in a magnetic field. The signal comes from transitions between spin energy levels via quantum resonance.

- Atomic clocks work because atoms have extremely stable quantised transition frequencies (hyperfine splitting). Given its quantum nature and the fact that time is a relativistic quantity, atomic clocks can be used to see how time is influenced by general relativity and quantum mechanics at the same time. The “quantum logic” clock achieves a systematic uncertainty corresponding to around 19 decimal places of accuracy,

- GPS requires atomic-clock timing based on quantum hyperfine transitions. Without quantum frequency stability, positional accuracy would drift rapidly.

- One type of electron microscope, the scanning tunnelling microscope operate because electrons can cross classically forbidden barriers via quantum tunnelling. Writing/erasing of flash memory also requires quantum tunnelling.

- Superconductivity can only be explained by quantum mechanics. The occurrence of the Meissner effect indicates that superconductivity cannot be understood simply as the idealisation of perfect conductivity in classical physics.

- Solar panels work because photons create electron–hole pairs via the photoelectric effect in a band structure. Check out the quantum dot solar cell.

- Chemical bonding exists because electrons occupy quantised orbitals. The periodic table and material properties follow from quantum mechanics, not classical electrostatics alone. Check out quantum chemistry.

- Quantum key distribution works because measurement disturbs quantum states and unknown states cannot be copied (no-cloning theorem). Security comes from physical law, not computational difficulty.

- Quantum computing relies on superposed and entangled states.