Wikipedia tells is that the Villa Vauban is an art museum in Luxembourg City. This is not quite true in that the Villa Vauban is the art museum of the city. A subtile difference, but a difference never the less. In fact the city has two museums, Villa Vauban and the Musée d’Histoire de la Ville, whereas other museums found on the territory of the city are in fact “statermuséeën” (national museums).

Wikipedia does manage an excellent little introduction to the Villa Vauban itself. The classical building we see above was a private bourgeoise residence built in 1873. It gets it name from the fact that it was built on the site of a fort constructed by Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633–1707) as part of the city’s defences. Above we can also see the contemporary extension that was actually completed in 2010.

The museum is located in a park laid out by the French architect Édouard André (1840–1911), one of the leading landscape architects of his day. Above we can see the garden around Villa Vauban, before the construction of the new extension.

The garden of the museum itself is in a larger band of gardens that includes the larger municipal park of Édouard André (with the kinnekswiss, the most extensive lawn in the city park), the Stadtpark (with its pirate ship playground), and the Parc Edith Klein (with its pond). There is even a path linking the whole area to the Parcs de la Pétrusse.

For a better idea of the exact location of Villa Vauban check out this map of the city.

The collection

Villa Vauban is home to the city’s collections which are composed of Dutch painting from the Golden Age and French painting from the 19th century, as well as paintings, sculptures and engravings by European artists from the 17th to the 21st century.

The first collection is of the banker Jean-Pierre Pescatore (1793-1855) and is made up primarily of 17th-century Dutch paintings, contemporary French works as well as sculptures and drawings. The second collection is of Leo Lippmann (1808-1883) consisting mainly of 19th-century art. The third collection belonged to Frederic Hochhertz, and is mostly comprised of history paintings, still life, and portraits. The Dutch Golden Age collection includes works by Gerrit Dou, Jan Steen, Eugene Delacroix and Jules Dupré.

Our visit

Our visit was on a cold Wednesday afternoon in October 2023 (the museum is closed on Tuesday’s). We saw four other visitors.

The museum consists of only a few rooms, and can be visited comfortably in 1-2 hours. Here is a short video introduction.

There was a one-room temporary exhibition entitled “Les animaux dans la gravure“, which we found less than impressive.

We started our visit with the multimedia projection entitled Immersive Space “Art[e]motion”. It’s a kind of introduction to some of the works on show. The animation is amusing for a couple of minutes, but I personally found it technically banal and the images of poor quality.

However I can recommend an excellent video introduction “La Villa Vauban le musée d’art de Luxembourg Commentaires & Infos“.

In addition to the private collections on show there is a room dedicated to the royal collection. I found it rather ‘conventional’ but clearly a lot of money had been spend on the frames.

Le roi boit by Mattheus van Helmont

The theme of the painting was very popular in Flanders. When the king of the Epiphany celebration, who is drawn (if he has not been designated) by the bean in the cake, raises his glass, everyone shouts “Le roi boit!” (The king drinks). Pieter Brueghel and Jacob Jordaens particularly enjoyed illustrating this popular tradition.

In the painting by Mattheus van Helmont we see the light entering the room through the small paned window, the table set in front of a curtain, the figure of the king, and that of the woman with the child on her knees, all are inspired by the works of Brueghel and Jordaens. The kitchen utensils placed on the floor are borrowed from Matheus van Helmont’s master, David Teniers, who used them in his alchemist interiors. This theme was painted more than once by the artist, since another version was sold at auction in 2020 for €20,000.

Mattheus van Helmont painted an abundant number of genre subjects, particularly village scenes, markets and kermesses, peasant interiors and alchemists’ workshops. It’s also mentioned that he painted Italian markets and fairs, which might suggest he visited Italy at some point in his career.

Le Canal Grande vu du Campo San Vio by Le Canaletto

I’ve always been a fan of Canaletto, and here we have “Le Canal Grande vu du Campo San Vio“. And as you can guess, this is not the only version painted by Canaletto. One is held in the British Royal collection, and another is in the Musée Thyssen-Bornemisza.

I can look for hours at the details of his vedute and capricci of Venice, Rome, and London. This is one of his many panoramic views of the waterways of Venice.

Le pont d'Avignon by Isidore Dagnan

I was particularly attracted by the sense of light (soft evening sunlight) and how it highlighted the architecture of the remnants of the Saint-Bénézet bridge, commonly called the Pont d’Avignon.

Isidore Dagnan (1794-1873) was known mainly as a portraitist and history painter, specialising in military subjects, but he also executed some landscapes. His works have been offered at auction multiple times, with prices ranging from $1,217 to $82,134, depending on the size and medium of the artwork.

Jeunes Napolitaines by Guillaume Bodinier

Le Penseur by Auguste Rodin

Before leaving the museum building we went to see The Thinker (Le Penseur) by Rodin. In many ways there is no ‘original’, however the first of the familiar monumental bronze castings was made in 1904, and is now exhibited at the Musée Rodin, in Paris. The work usually is depicted as a nude male figure of heroic size sitting on a rock.

The Thinker has been cast in multiple versions and is found around the world, and there are a multitude of sculptures of different study-sizes and plaster versions (often painted bronze). Some newer castings have been produced posthumously and are not considered part of the original production.

The version in the Ville Vauban is actually a very small reproduction.

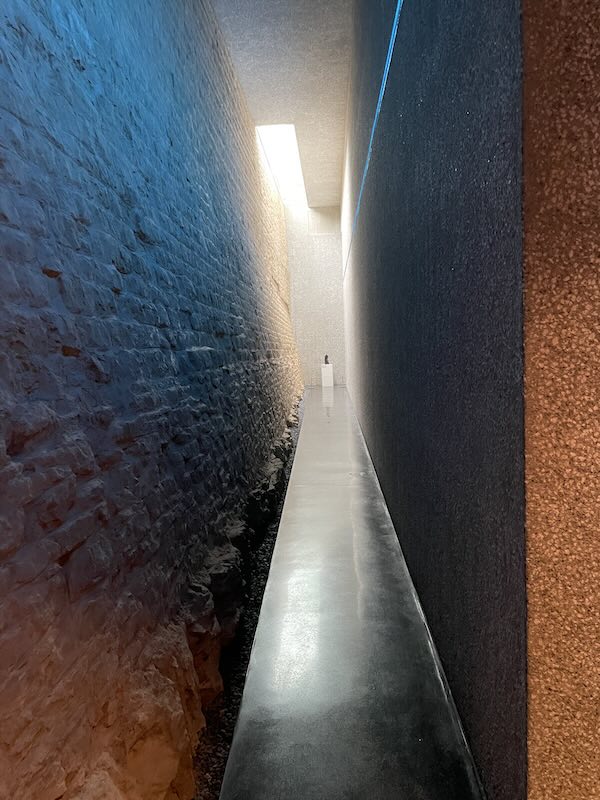

What I found more intriguing was that the small reproduction is actually set at the end of a dead-end underground corridor that runs along a portion of the original city defensive wall.

Made me think… at least about how they discovered the wall.

Back into the garden

Entering and leaving the museum we were struck by a ridiculous resin ‘statue’ called “La Grande Tempérance” by Niki de Saint-Phalle (I guess one of her Nanas).

My understanding is that in 1995, while Luxembourg city was then the “European Capital of Culture“, eleven works by Niki de Saint-Phalle were exhibited in Luxembourg public places. “La Grande Tempérance” was ultimately bought by the City of Luxembourg, the “Entreprise de Poste et Télécommunications” (Luxembourg Post) and the bank now-called BGL-BNP Paribas.

The ‘statue’ has moved around, and after a recent restoration, finally landed in the Villa Vauban. I don’t like this type of work, but set in a rather brutalist office landscape I can understand that it can cheer people up as the cold rain hits them in the morning (and perhaps reminds them of the more important things in life). But in the garden of Villa Vauban it just looked out of place.

On the other hand, Enlancement (Embrace) by the Luxemburger Lucien Wercollier looks so settled in the garden it’s easy to miss it (possibly with good reason). I applaud the desire to support and offer space to local artists, and I’m certain that on a sunny afternoon I might have seen this statue in a different light.

Centaure by François-Xavier Lalanne

Centaure is a surrealistic bronze sculpture of a centaur created by François Xavier and Claude Lalanne in 1985. I personally find this bronze the most interesting in the museum garden, yet it is hidden away in a corner.

Les Lalanne, as they became known collectively, were one of the most dynamic French art couples of the 20th century. Courted by Surrealists and celebrities alike, their distinctive blend of fine and decorative arts, which was based on naturalistic forms, has made their work highly prized by contemporary collectors.

It is known that they rarely collaborated together on individual pieces, instead they “co-created”. While François-Xavier favoured sculpting animal themes, Claude worked with plants and the human form. François-Xavier could certainly ‘drop a few names’ into a conversation, since he rubbed shoulders with René Magritte, Salvador Dalí and Constantin Brâncuși.

I wonder what the symbolism is in this sculpture. We see a creature from Greek mythology with the upper body of a human and the lower body and legs of a horse, a creature that was wild and untamed. Does the eyeless helmet mean that it has been tamed, but then for what purpose? Does this stature point to Chiron who was called the “wisest and justest of all the centaurs“. Are the callipers and the measuring rod symbols of Chiron as an educator?

Does the fact that the centaur is blind refer to the famous statement of Dalí “Surrealism is destructive, but it destroys only what it considers to be shackles limiting our vision”?