A living museum of landscapes, climates, and life-styles

The autoroute E25 (Italian A5) links Palermo in Italy with the Hook of Holland, and runs through the Aosta Valley and the Mont Blanc tunnel.

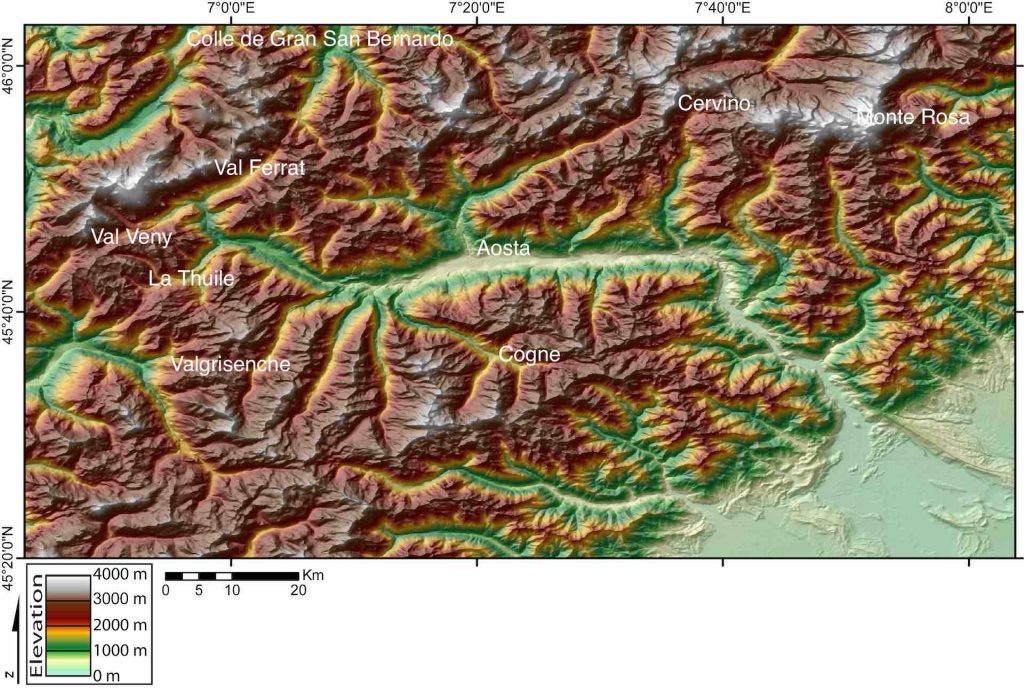

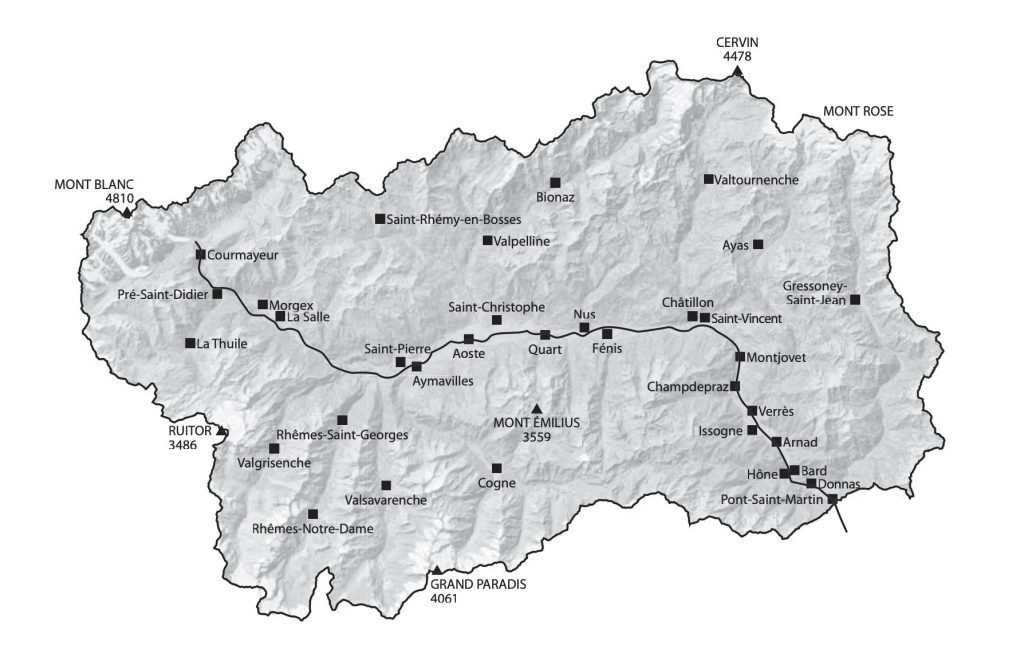

The Aosta Valley has 30 major tributary valleys, including those for Mont Blanc, Monte Rosa, Gran Paradiso and the Matterhorn (Cervino in Italian). With Mont Blanc at 4,810 m, the valley is the highest region in Italy.

Technically the Aosta Valley is defined as a Alpine valley system surrounded by the great peaks of the Pennine and Graian Alps, i.e. the Pennine Alps, or Valais Alps, are north of the Aosta Valley, whereas the Graian Alps cover both the south of the valley and the Mont Blanc range. This division defines the separation between the western alps (with Monte Blanc representing the Graian Alps), and the central alps (with Pointe Dufour, Monte Rosa representing the Pennine Alps).

Together the Pennine and Graian Alps cover the whole mountain zone of the Dora Baltea hydrographic basin (the river flows down what is called the Aosta-Ranzola fault line).

Driving along the valley of the Dora Baltea means, from a geological point of view, crossing a large portion of the structures that make up the backbone of the Western Alps.

The ‘Alpine orogeny‘ is the formation of a mountain chain which took place between 20 and 100 million years ago. The enormous thrusts due to the displacement of the the African and European ‘continental plates‘ gave rise to the overlapping of the rocks that formed the margins of the two continents and the bottom of a sea called ‘Tethys‘. These grandiose dislocations gave rise to kilometer-sized rock folds and flakes, which were pushed deep into the earth’s crust where temperature and pressure were very high. So much so that the rocks underwent a profound transformations of their structure, which mineralogists call ‘metamorphism‘.

Around 20 million years ago the compressive thrusts ceased and an impressive uplift motion of the Alpine Chain began which, currently in the Western Alps, is still ongoing with values of the order of 1 mm/year. The uplift led to the definitive emergence of the ‘catenas‘ (variations of soil types over a single slope).

Ever since the Alpine Chain emerging, it has been attacked by erosive processes due to water, frost and wind. In these 20 million years they have removed a thickness of rocks of the order of thousands of metres. Glaciers and streams have dug the valleys so intensely as to expose the deepest geological structures.

Driving up from Torino the first town in the Aosta Valley is Pont-Saint-Martin, but just three kilometres later you see the entrance to the valley protected by the Forte di Bard (which became even more famous when it appeared in “Avengers: Age of Ultra“). The rock outcrops seen in this part of the Valley are from the original African continent. Hard and massive, they form the steep slopes of the lower valley and the characteristic hump smoothed by glaciers on which the unmistakable fortress sits.

This strip of Africa continues up to the Verrès basin. The mountains that dominate the small town are made up of rocks derived from the transformation of materials from the ancient Tethys ocean. One rock is a soft ‘calcescisti‘ (calcareous schist), coming from marine sediments. Another is a variety of harder ‘pietre verdi‘ (green stones, which is actually different varieties of green marble). This is the result of the metamorphic transformation of the basalts of the original ocean floor and other rocks related to submarine volcanism. Among these we find the serpentinites, which constitute the so-called ‘green marble’ of the Aosta Valley, or more specifically classic dark Verde Alpi (with lighter green veining), Verde Aver with white veining, the medium coloured Verde Chiesa and the Verde Saint Denis (there is also a Corbata Black marble).

The calcareous schist and ‘pietre verdi‘ are the most widespread rock forms in the region and continue along the valley of the Dora Baltea for many kilometres beyond Aosta.

Where the hard ‘pietre verdi‘ emerge, there is a mix of steep crags carved by the Dora Baltea and raised rock formations often dominated by medieval castles.

Where the softer calcareous schist dominate, the valley opens up into large hollows as in the central stretch of the valley, where the city of Aosta stands, and, further upstream, up to Saint-Pierre (below) and Villeneuve.

Upstream of Villeneuve the morphology of the valley changes abruptly. Now it’s the crystalline base of the European continent, whose hard metamorphic rocks form steep, craggy walls, interrupted by short rock shelves. The Dora Baltea had cut a long and deep gorge, which forced the Romans to carve their roads in the rock walls overhanging the river.

The valley widens again in its final portion, between La Salle, Morgex and Courmayeur, thanks to the first presence of a strip of substantial ‘black schists’, then followed by a new horizon of calcareous schists. This last stretch of the valley is dominated by the great mass of the highest mountain in Europe, which closes the Aosta Valley. The erosion, in this case, has concentrated on the edges of the granite massif, excavating the two valleys of Ferret and Veny at the foot of the great wall of rocks and ice, and creating the Dora Baltea (below).

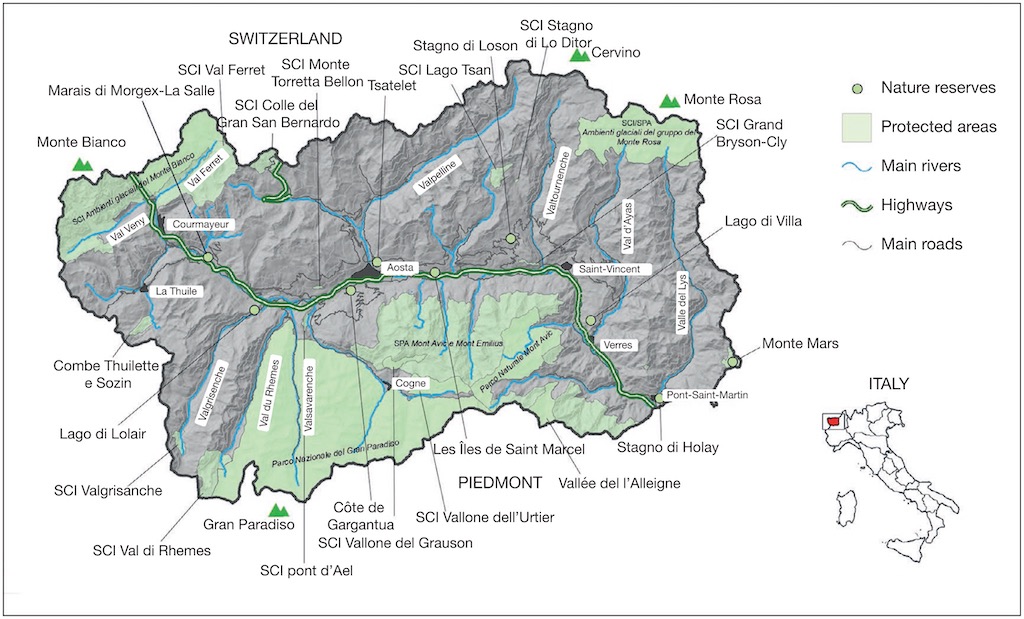

As you drive through the valley the most obvious features are the mountains and castles, but in fact more than 30% of the regional territory is under environmental protection, with Nature Reserves, a National Park (Gran Paradiso), a Regional Park (Parco Naturale Mont Avic), nearly 30 important conservation areas, five Special Protection Areas (for wild birds) belonging to the European ecological network Natura 2000, and four Alpine botanical gardens.

SCI means “site of Community importance”, or SIC “site d’importance communautaire”, and, as far as I know, nearly 450 different Italian Alpine biogeographical sites were declared as such in 2018.

Driving up to theMont Blanc tunnel you see mention of the two mountain passes, the Great St Bernard Pass (Colle del Gran San Bernardo) and the Little St Bernard Pass (Colle del Piccolo San Bernardo). However in 1694 the nobleman Philibert-Amédée Arnod, by order of governor of the duchy of Aosta, compiled a report on the passes along the entire Aosta Valley border. He documented 13 passes open towards France, 12 to Switzerland, 7 to Val Sesia or the Biella area and 7 to the Canavese valleys. At the end of the 17th century in the Aosta Valley territory about forty passes were commonly used for trade, the altitude of which is, almost for all, higher than 2,500 metres.

These high passes, during the high temperatures and scarce snow of the late Middle Ages were open for several months a year. After the mid-16th century, with tail-end of the Little Ice Age, their crossing became increasingly difficult mainly due to the ever longer and more abundant snow cover. The highest passes were even covered with perennial ice. Arnod advised that to cross the Galisia (3002 m), Breuil of Chavannes (2862 m), Fenêtre de Durand (2802 m), Crête Séche (2995 m), Collon (3114 m), or Teodul (m 3300) “you have to walk several hours on the glaciers“.

Geology of Valle d'Aosta

Despite the Aosta Valley (population only 126,000) being the smallest administrative area in Italy it is home to a very wide range of altitudes, ranging from 400 m to 4810 m, which suggests a complex lithological, geological and glacial history. Moreover, the high mountains function as barriers to perturbations from the Atlantic as well as from the Po Valley, e.g. so it is home to some of Europe’s highest vineyards located on south-facing slopes of the valley up to about 1300 m.

In fact the average altitude of the region is about 2100 m, which is nothing more than an indication of how ‘mountainousness’ the region is. At that altitude and location snow and frost would last about eight months, leaving just sixteen to eighteen weeks ‘free’. This period is too short for agricultural plants to carry out their vegetative cycle, and the area would not be able to support a permanent human settlement. Fortunately about 20% of the regional area is below 1500 m and nearly 60% sits between 1500 and 2700 m (the limit of the Alpine zone). The remaining 19% is represented by high alpine lands, over 2700 m. About 40% of the total area is rocky (and includes more than 175 glaciers) and represents the dominant macro-habitat. This is followed by forests (27%, mainly coniferous), rupicolous (i.e. rocky) grasslands (17.4% including pseudo-steppic grasslands) and pastures (12%). Wetlands were once widespread throughout the whole flood plain of the main valley, but are now only found in the central part of the region.

The valley itself was created by the convergence of the Eurasian plate and Adriatic plate, at the so-called Periadriatic Seam. This occurred more than 20 million years ago (post-late Oligocene), but what we see today was later affected by a number of other physical phenomena, the most importing being glaciers of the Pleistocene period (what most people call the Ice Age), which covered an extensive period from 2.58 million years ago through to 11,700 years ago. So the valley was directly created by glacial modelling, both erosional and as depositional landforms. Also glaciation directly influenced the slopes that we now see, as decaying glaciers allowed gravity to take over, and instabilities released landslides (the results of which today cover about 15% of the valley). Alongside this, erosive activity of watercourses affected all of the Aosta Valley territory through the progressive deepening of glaciated side valleys, and the erosion of glacial landforms and deposits. Important fluvial deposits and landforms are present on the valley bottoms, as are imposing mixed alluvial and debris-flow fans, products of recurrent meteorological events (the last occurring in 2000).

The Dora Baltea

The name of Dora comes from an ancient word of Indo-European origin and generically indicated a watercourse. We find its root in the name of Russian rivers such as the Don and the Donets, as in that of the Danube or the Drava or in the Iberian peninsula in that of the Duero. Therefore it becomes necessary to specify more precisely the exact river by combining it with an adjective or the name of the valley through which it flows. In the the Aosta Valley the Dora was called Baltea from the Latin name of its major tributary, the torrent Buthier, known in Latin as “Balteus”.

This long ‘plain fjord’, which originally was give the name “La Plaine“, represents just 4% of the Aosta Valley territory but is home to 70% of the regional population.

The Dora Baltea valley is a long and deep furrow that extends for about 100 kilometres from the most imposing mountain mass of the Western Alps. At 1300 meters above sea level it forms from the confluence of its two spring branches, the Dore di Val Veny and Val Ferret. It leaves thevalley in the Canavese plain, just 300 m above sea level.

The Valle d’Aosta represents just a tenth of the southern Alpine slope, but collects more than a third of the entire glacial cover of the Italian Alps. It is by far the most intensely glaciated area in Italy, despite the fact that a significant reduction in glacial masses is currently underway. In 1882, at the first topographical survey, the glacialised area of the Valley was 237 square kilometres, today it is just 100 square kilometres.

The melt waters of the glaciers give rise to numerous streams, the largest among them flow through tributary valleys, each of which has a development of between 20 and 30 kilometres.

The Dore of Val Ferret and Val Veny collect the waters of the Mont Blanc glaciers, and create the Dora Baltea. A little further south, near the center of Pré-Saint-Didier, the Dora di Verney flows into it, which descends from the La Thuile valley. Further downstream the Dora della Valgrisenche comes from the valley of the same name. Near Villeneuve, the waters of the Dora di Rhêmes and those of the torrent Savara reach the Dora Baltea. The latter comes from Valsavarenche and collects the melt waters of the glaciers on the western side of the Gran Paradiso. Water from the eastern side of give rise to the Grand-Eyvia stream which irrigates the Cogne valley and flows into the Dora Baltea near Aymavilles.

The hydrographic network of the Pennine Alps gathers largely in the Buthier torrent, which is the most important tributary of the Dora Baltea. This carries the waters of the Gran San Bernardo valley, those of the Vallone di Ollomont and those of the Valpelline. Near the town of Châtillon, the Marmore torrent descends to the Dora Baltea, which originates from the glaciers of the Cervino and Grandes Murailles and flows through the Valtournenche. The melt waters of the western sector of Monte Rosa collect in the Evançon torrent which runs through the Champoluc Valley and reaches the Dora Baltea at Verrès, while those of the eastern sector give rise to the Lys torrent, the watercourse of the Gressoney valley which flows in Dora at Pont-Sant-Martin.

This confluence marks the southern limit of the Valle d’Aosta basin which has a surface area of 3262 square kilometres. It has an average annual outflow of about 3½ billion cubic metres, about a third comes from glacial ablation and therefore affects the months between May and September. The result is a typically glacial regime with maximum flows in late spring and very accentuated low temperatures during the winter when the precipitations are mostly solid and in very limited quantities. The Dora Baltea has a very interesting peculiarity, because it is the only Italian watercourse that has a flow coefficient higher than 1. This means that the mass of water that it drags downstream, despite the losses due to evaporation and the permeability of the land, is greater than that which the precipitations bring to its basin. This phenomenon is due to the fusion of the glacial masses and to the direct condensation of atmospheric humidity on the surface of the glaciers themselves.

Pulling all this together makes the Dora Baltea the longest and most water-rich river in the Western Alps.

It would be a mistake to simply see the torrents and rivers in the Valley as purely hydrographic features.

Watercourses (torrents, rivers, streams, etc. collectively called ‘rus‘) have represented, since the Middle Ages at least, an important point of reference for the local communities. Sometimes they became boundaries between seigniories or even, as happened with franchises granted in 1191 by Count Thomas I to the city of Aosta, the proclamation of its legal borders. In this document the Count indeed established that his new regulations must apply within a perimeter of which one of the sides was represented by the ‘rivus ville‘ which skirted the ramparts to the north and west of Aosta. This town ‘stream’ was already mentioned in a document of 1186, and was part of an older watering network.

So already there were irrigation rights, and therefore man-made channels (or even canals). Irrigation rights were already known in Roman times, and in deeds concern cultivated land there was mention of the land being endowed with ‘aquaricia‘, that is to say with watering rights. However, the information was never accompanied by a precise description of the stream from which the water could be drawn.

In fact, the first indications of a water network dates from the end of the 13th century. For example, the ‘ru de Joux‘ which took water from the torrent of Saint Barthélemy was created around 1250, the ‘ru of Jovençan‘, was the subject of an agreement between in 1252 between the bishop and the lords d’Aymavilles, and the ‘ru Baudin‘, was dug in the vicinity of Aosta in 1287. According to tradition, some of the irrigation waterways were created by a few local nobles. Sometimes it was priests who took the initiative, as was the case with ‘ru Pompillart‘ where the parish priests of Saint-Laurent d’Aoste, Saint-Christophe and Quart asked the Count of Savoy for permission to build a waterway.

However, historians have underlined the role of individuals in the construction of irrigation channels. Acts of inféodation very often included requests for the right to build irrigation channels. For example, on November 23, 1400 it was the inhabitants of Gignod who begged the bailiff to obtain the right to build channels to irrigate their land. In some cases the requests were made after irrigation channels had been built, so obtaining a concession to avoid later prosecution.

Waterways were certainly the occasion for frequent and violent disputes which sometimes lasted for centuries and divided communities and individuals with opposing interests. Some disputes have been preserved in the records of trials. The first document dated from 1331 where someone had decided to dig a brook in the common pastures of the parish (probably planning to transform them into cultivated meadows). The community asks the bailiff to have it destroyed. This highlighted the fact that the local economy was strongly linked to the use of common pastures, and that an irrigation cannel implied cultivated meadows and consequently the privatisation of the common lands. In the majority of cases, however, the conflicts related to the fact that different communities were fighting over the water flowing from a glacier and which was insufficient to meet everyones agricultural needs.

Most of the documents focus on the building of irrigation channels, streams, brooks, etc., and not the reason for the need for more irrigation. However, a few highlight the problem of aridity and mention the advantages that a local noble might have in higher rents.

The period between the 14th and 15th centuries saw a profound change in the way of exploiting the Valley territory. There was an undeniable transition from natural pastures to cultivated meadows, and from sheep breeding to cattle breeding. The increased need for water for the meadows forced the local population to recognise that water resources were essential for their new economy. It would appear that everyone quickly agreed that irrigation was an economic necessity.

Valle d'Aosta - a home to early Man

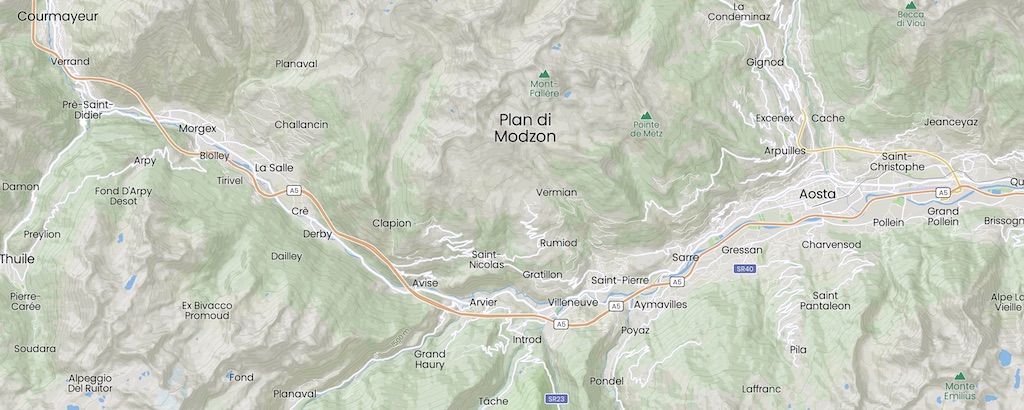

As you drive through the valley one thing that is certainly not visible is how early Man might have occupied the region. Over the last few years, several archaeological remains have been found in the Plan di Modzon area, on the southern slope of Mont-Fallère (3,061 m) in the middle Aosta Valley.

The Mont-Fallère archaeological settlements were first discovered only in 1998 at a high altitude, approximately 2,250 m, and other sites were discovered in 2008 and 2011. The idea is that over time glacial and landslides created a wide and slightly sloping surface (Plan di Modzon at 2,240 m to 2,300 m) with easy access, a good view of the surrounding mountains, and directly overlooking the main valley floor.

This was quite different from other deeper and narrower tributaries. The reality was that other mountain areas of the same altitude were difficult to reach from the valley floor. In addition the surrounding mountains actually protected the Plan di Modzon from debris and avalanches, and deep depressions ensured plenty of water, but avoided flooding. The irregularities in the mountain walls provided protection against approaching animals, and sitting just above the forest line provided access to wood.

So the archaeological data suggests that the Plan di Modzon area represented a very specific site for ancient human establishment. Some other archaeological settlements have also been found in other sites within the Alps at the same altitude range and with similar morphological and vegetation features.

One archaeological site on Plan di Modzon shows a lithic (i.e. stone) industry of rock crystal (hyaline quartz) from the Mesolithic period, specifically Sauveterrian (ca. 6500-4500 BC). About 3,000 artefacts have been identified, and radiocarbon dating on charcoal remains suggest the area was occupied as early as ca. 6700-6490 BC.

Other sites on Plan di Modzon suggest Copper Age settlements (ca. 3500-1700 BC). The more recent archaeological artefacts (Copper Age) were found on top of the bedrock, but some of the more ancient artefacts were discovered sitting above them. This reversed stratigraphy suggests that the older artefacts had been washed out from colluvium (sediments), and it’s possible that once discovered were being reworked by a later culture. Radiocarbon dating on two different charcoals from a hearth have been dated to ca. 3030-2870 BC and ca. 2620-2400 BC.

Key dates in the history of the Velle d'Aosta

Following the work of Alessandro Celi, here are some of the key dates in the history of the Valle d’Aosta.

His position is that the entire history of the Aosta Valley was determined by the possibility or not of keeping the Alpine passages open during the winter. He mentions that during Roman times, when the average temperature was a few degrees higher than today, the snow was not an insurmountable obstacle for the legions crossing the Grand-Saint-Bernard to reach the upper Danube. On the other hand, the fall in the average temperature at the end of the 16th century triggered a crisis in commercial relations which, together with the constraints of the international politics of the time, had serious repercussions on the Aosta Valley economy.

Archaeological excavations suggest that, unlike today, the most populated places were not in the plain in the centre of the main valley, but in the hills, at an altitude between 800 and 1,200-1,400 meters. In fact the Dora Baltea, until the middle of the 20th century, was not dammed in such a way as to prevent the formation of marshes (with the risk of flooding and as a source of disease).

These prehistoric villages (ca. 2500 BC) were not in the main valley, but were in side valleys and along the paths that cross the Alps in the shortest possible way.

There is evidence that the Celtic people of the Salassi probably arrived in the Valley during the great migrations of the Celtic peoples of Europe between the 8th and 4th centuries BC. They then mixed with the pre-Indo-Europeans in place since Neolithic times.

The first key date in the history of the Aosta Valley is the founding of Augusta Praetoria Salassorum (Aosta) in 25 BC. The city was inhabited by the Praetorians in the territory of the Salassians so that legions had a fast and safe way of communication between Italy and the upper valley of the Danube, the famous Danubian Limes which was to become the border between Latin civilisation and the barbarian peoples. Therefore Aosta was born as a military city and the entire Aosta Valley was in many ways a military invention. So the Valley was marked forever by the domination of Rome, both from an archaeological point of view and from a linguistic and cultural point of view.

At the end of the 6th century (575 AD) the Aosta Valley was politically separated from the Italian peninsula, since it became part of the Barbarian kingdoms that had their centre between Lake Geneva and the Rhone Valley. They established a boarder at Bard, where a large rock locks the main valley. So the barbarians coming from the west became the masters of the Aosta Valley, making it, over the centuries, a French-speaking region.

With the departure of the Romans, the Valley was initially controlled by the Burgundians, the Byzantines, then the Lombards before they ceded the Valley to King Guntram of Orléans and Burgundy in 574. The Carolingian Empire and the kingdom of Burgundy owned the region until the annexation of the Valley by Humbert 1st of the House of Savoy in 1032.

During the five hundred years between the year 1000 and the Protestant Reformation (ca. 1517) trade between the North and Italy passed through the Alps rather than by waterway. The House of Savoy was master of the Valley and in 1191 Thomas Ι, Count of Savoy, granted the Aosta Valley the “Charte des Franchises“, recognising the right to administrative and political autonomy (this right was maintained until the French Revolution). It also ensured the full freedom of the inhabitants against claims and taxes of the feudal lords, obtaining in exchange the complete loyalty of the city.

As early as 1191, when Thomas I was only 13 years old and under the tutelage of Boniface de Montferrat, he came to Aosta to settle with Bishop Valbert a certain number of questions relating to the exercise of royal rights. On the same occasion the citizens of Aosta expressed, through their pastor, their concerns about the lack of a stable authority, able to prevent the violence of the local lords and the arbitrary actions of county officials. Following this meeting an agreement was concluded between the count, the bishop and the citizens and bourgeois of the city, and recorded in a “Charte des Franchises” which marked a fundamental stage in the relations between the Aosta Valley and the Humbertian dynasty. By this act of an essentially contractual nature, the count undertook in particular to defend the life and property of the clergy and the inhabitants of Aosta and not to claim any financial benefit which would not be accepted beforehand by the citizens themselves. They in turn pledged to reserve their loyalty to him and to bring him their aid in case of war.

So the Aosta Valley region became an important communication route for trade to France, England and western Germany. Still today the valley is home to many castles built during the Middle Ages. The influence of the House of Savoy remained almost uninterruptedly until 1946.

The Aosta Valley became a quasi-independent state in 1536, when the domains of the House of Savoy were occupied almost entirely by the King of France. It was the time of the wars between France and Spain for the control of Italy. The Duke of Savoy, allied with the Habsburgs, had seen his lands invaded by the French armies. In February 1536, only the Duchy of Aosta still remained free from foreign occupation.

The Aosta Valley was above all a fundamental military corridor for communications between France and Italy, and obviously its control was therefore a fundamental target for armies at war. The only way to prevent an invasion of the valley was to close the Alpine passes between the two parties.

An army of about 4,000 men, about 6% of the population, was created by a government called the Conseil des Commis and by the signing several treaties. The result was that the Duchy of Aosta closed its passes to the passage of the armies at war, and thus avoided an almost inevitable French occupation.

Thus, the Duchy of Aosta became a state in its own right because it possessed political power, an army, and it was internationally recognised. However, instead of proclaiming independence they remained faithful to the House of Savoy and paid homage to Duke Emmanuel-Philibert, when the latter returned to the lands of his ancestors, after the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559.

Interestingly the minutes of the Conseil des Commis were written in French, which means that the Duchy of Aosta was the first state to use French as the official language in its documents.

In 1661, the bishop of Aosta, the Savoyard Philibert-Albert Bailly addressed to the Papal Court a memorial supporting the right of his diocese to be exempted from the payment of tithes due by the Italian dioceses. He explained that the Vallée d’Aoste did not belong to Italy, neither only from the point of view of the ecclesiastical organisation, or geographically. It was an ‘intramontane state’, a formula that would be used in the following centuries to explain the particularity of the region.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw the duchy gradually lose its autonomy from the central power. In 1770, Charles-Emmanuel III refused to take an oath to the Aosta Valley prerogatives, and in 1773, he promulgated the Particular Regulations for the Duchy of Aosta (Règlement particulier pour le duché d’Aoste), a code of laws which replaced the customs and usages hitherto followed throughout the duchy. So the Conseil des Commis lost its power.

This change was certainly motivated by the absolutist policy of the time, but also by the weakness of the Aosta Valley ruling class. In fact, between the 17th and 18th centuries, several noble families disappeared, especially after the great plague of 1630, which killed half, if not two-thirds, of the Aosta Valley population, a demographic debacle from which the region did not recover until the 20th century.

On March 17, 1861 Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy. Following the cession of Savoy, the percentage of French-speaking subjects of the House of Savoy fell from 12.5% to 0.2%. In fact, only the inhabitants of the Aosta Valley and those of the valleys of Vaud religion, at the west of Turin, maintained the use of the French language. They became the first linguistic minority in the Italian State.

The years between the unity of Italy and the Great War saw the Aosta Valley reduced to a dead end, as the new border prevented the traditional relations between the Valais and the Savoy. Without an international road or a railway (this arrived in Aosta only in 1886, and the Mont-Blanc tunnel remained a simple project until the 1960s), the Valley experienced several waves of emigration, especially to Switzerland, France and the United States.

After the losses due to the Spanish Flu epidemic (1918), the Valley became the destination of thousands of workers, coming from other regions of Italy to work in the steel mills created during the war. However, native inhabitants of the Valley continued to leave for other countries. In this way began the loss of the French-speaking identity of Valle d’Aosta. It would appear that this demographic change was intentionally aimed at replacing the local population with Italian-speaking immigrants, more controllable from the political point of view. This situation worsened during the fascist dictatorship (1922-1943), which established the Province of Aosta, uniting part of the province of Turin to the Valley (Canavese with its capital Ivrea), always with the aim of gradually erasing the local French-speaking identity.

After unification the Aosta Valley built an identity based on the ‘diversity’ of the its people (i.e. French-speaking mountaineers, good Catholics and proud of their tradition of freedom and privileges). However the fascist dictatorship underlined the themes of the Roman spirit of Aosta and the history of the Valle d’Aosta with the House of Savoy. The aim was to demonstrate the profound Italian character of the Aosta Valley people, a people believed to be of Roman (and not Celtic) descent, to whom history has entrusted the role of “guardian of the Alps”, or “first sentinel of Italy”. Historical heroes of the Valley became the leaders who were extremely loyal to the Savoys, the soldiers who fought heroically against the French invaders, and above all the Alpini of the Fourth Aosta Battalion, the heroes of the Great War who gave their lives for the Italy.

After the fall of Mussolini, in 1943, Émile Chanoux, leader of the Aosta Valley Resistance, who on December 19, 1943 met in Chivasso with the representatives of the Vaudois valleys, to write a document, known as the Déclaration de Chivasso (Declaration of Chivasso), in which they demanded the transformation of Italy into a cantonal state, according to the Swiss model.

The declaration is a fundamental document in Italian federalist thought, since it united the administrative side (the reorganisation of the Italian State after the war), with the ethnic side (the safeguarding of the linguistic minorities of the Alps).

Finally on February 26, 1948, a Constituent Assembly, set up to establish the fundamental laws of the new Italian republic, decided that the Valle d’Aosta, would be one of five Regions with a special status within the Italian State (the others were Sicily, Sardinia, Trentino-Alto Adige and Friuli).

The new statutes gave several competences to the Regions, but it also contained within it a series of norms capable of making it almost inapplicable. Indeed, it was not until 1981 that the Italian State granted the Regions the necessary financial means so that it could set up a truly autonomous administration.

French and Italian are both official languages in the Valley. In fact it was on September 22, 1561 that Emmanuel Philibert (1528-1580) promulgated the Edict of Rivoli, which provided, in the Duchy of Aosta as in the other provinces, for the use of the vernacular (“each province its own”) instead of Latin in official documents. “Having always and at all times been the French language in our Pays d’Aoste more common and general than any other“, affirmed the duke, “and having the people and subjects of the said Country aware and accustomed to speaking the said language more easily than anyone else“, it would henceforth be forbidden to use Latin “both in proceedings for trials, and acts of justice, as well as in drawing up contracts, instruments, inquiries or other similar things“, because “the Latin language ( …) is so intelligible to the people“.

According to article 38 of the Italian constitution of February 26, 1948, “In the Valle d’Aosta the French language and the Italian language are equal“.

In 1861, the unification of Italy radically changed the geopolitical location of the Aosta Valley, which became the extreme periphery and linguistic minority of the new Italian state. After an initial phase of great enthusiasm, a period of profound economic crisis affected the very identity of the Valley and its people. The cousins Savoyard became French, the Province of Aosta was suppressed, the tax burden almost tripled in the first decade of unification, and the first attacks on the use and teaching of the French language began. The people of the Aosta Valley ask themselves “Sommes nous français ou italiens?”, “Can one be Italian and speak French?”, “Was it worth fighting for the unification of Italy?”,…

Between 1860 and WW I, local history became an essential part of the culture of particularism (in its simplest form this refers to an exclusive connection to a group). While the identity question “Qui sommes nous?” arose among the cultural elites of the Aosta Valley, the French language, the history of Aosta Valley freedoms, and the specificity of the Alpine environment became founding elements of the new Aosta Valley identity. They were Italians, but were different. They lived in the mountains, they spoke French, and proudly cultivated the memory of particularism. For both conservatives and liberals in the local population, the use and teaching of French is not only a ‘right’ of the Aosta Valley, but a ‘sacred duty’, a duty to defend both the language and local traditions.

References

Alessandro Celi, “Nouvelles Perspectives dans l’Histoire Valdôtaine“