Any visit to the castles and strongholds in the Val d’Aosta must include the Castello di Issogne. As Wikipedia points out, it is one of the most famous manors in the region, and is noteworthy for its frescoed cycle of scenes of daily life from the late Middle Ages. And even more surprising, it’s also famous for the graffiti, also from the Middle Ages.

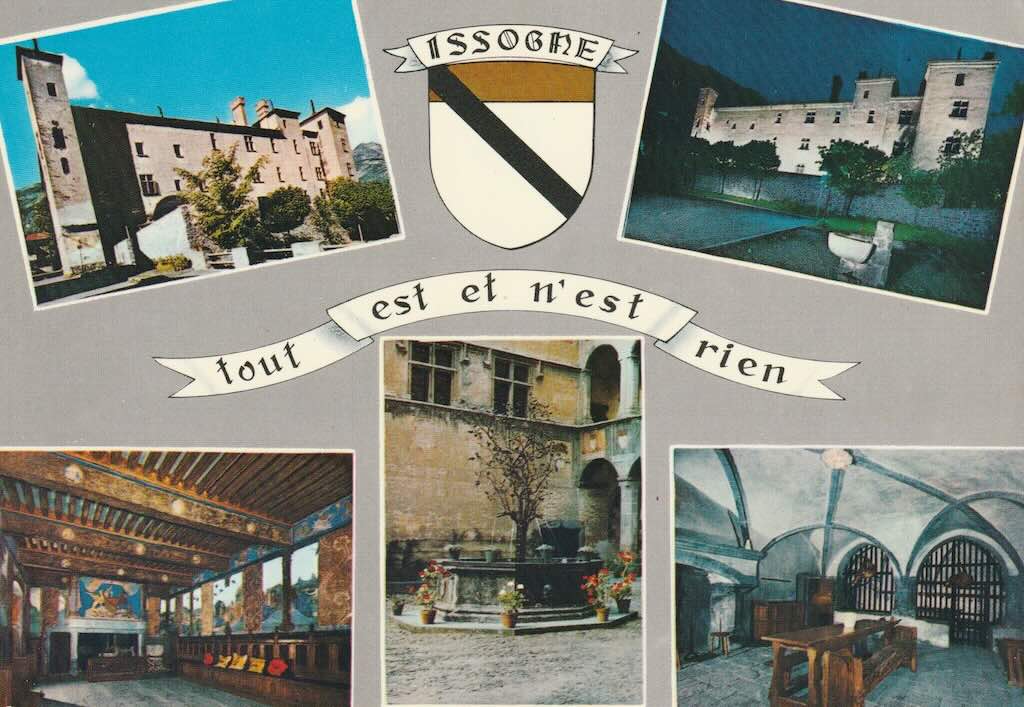

As seen above, it looks from the outside as a rather ordinary looking manor house, but as suggested by the old postcard shown below, inside it houses some of the most important artistic treasures in the valley.

There is parking nearby, and it’s a popular place to visit during the summer months. We visited in September 2024, easily found a parking space, and we were in a group of only two for the guided visit. So our visit was more like a chat with someone passionate about “his” castle, and it took about one hour.

Logic tells us that we should first look at the history of this castle, then look at the visit. But sometimes the history can be a bit boring for some people, so lets start with the visit, and push the history bit to the end of this post.

Setting the Scene

The castle of Issogne is not a grim medieval ruin, but rather a peaceful and well-preserved noble residence built to meet the tastes of a cultured personality. A person who returned to the Aosta Valley after having visited the most important cities of Italy and having studied in Avignon, Turin and Rome. Returning to the Val d’Aosta he set about building a quiet place of residence for his nephew and pupil Filiberto di Challant (Philibert de Challant in French) and for the child’s mother Margherita de La Chambre, widow of Count Luigi di Challant (Louis de Challant).

That person was (abate) abbot Giorgio di Challant (George de Challant, 1440-1509), son of Amédée de Challant–Aymaville, lord of Varey of the Fénis branch, commendator of the Collégiale de Saint-Ours and governor of Aoste. In his task of building/renovating the castle, Giorgio de Challant was helped by master Michie (or Michael) who also directed the works of the collegiate church of S. Orso, together with a master carpenter and cabinetmaker called Brace, the master painter Collinus and the master blacksmith Pantaleone de Ldaz.

A part of the fief of Issogne, which depended primarily on the bishops of Aosta, had already been purchased 1379 by Ibleto di Challant (Yblet de Challant) in exchange for a censo (ground rent or an annuity paid for the use of land) of 180 lire per year and a horseshoe. I’m not sure what “lire” is refereed to here, because there were many difference currencies in use in the different city-states. But my guess is that it refers to a silver coin, more valuable than the soldi, which were both more valuable than denari (the florin was in gold). Concerning the horseshoe, there was a period, due to the value of iron, where horseshoes were accepted in lieu of coin to pay taxes.

The remainder of the fief of Issogne was divided between the nobles De Verretio (of Verrès Castle), Alexini and De Turillia, all under the high jurisdiction of the bishops of Aosta. The part of the De Verretio had been devolved to the House of Savoy shortly before 1390 due to the extinction of that family, and the part of the Alexini had also been purchased by the same house. Thus, it was possible to invest these parts in Ibleto di Challant, who had also already purchased the portion belonging to the De Turrilia family. Thus Ibleto became the sole owner of the fief of Issogne.

The castle or fortified house of Issogne must have already been (or had become) a decent dwelling place because it hosted the Emperor Sigismondo on his return journey from Italy to Germany in 1414.

Wikipedia has a very extensive review of the Challant family tree, which shows that the Challant family died out in 1804 with Giulio Giacinto di Challant-Châtillon, who died at the age of 7. In 1837 Teresa, the last woman of the family, died and with her the Challant dynasty ended. The castle of Issogne passed to Giulio Giacinto’s mother Gabriella Canalis di Cumiana. From 1846 onwards, the castle and the archives of the Challants were inherited by the Passerin d’Entreves. The castle was sold in 1858 together with Verrès to a certain Alessandro Gaspard da Chatillon. From him it passed in 1869 to a Baron Mario de Vautheleret, from whom it came into the possession of the painter and connoisseur Vittorio Avondo in 1872.

The new buyer had a marked sensitivity for the architectural and artistic heritage of the derelict castle, and personally took care of the restoration and refurnishing, with a “team of young artists”, adhering with philological scrupulousness to the appearance that the building must have had in the 16th century. In 1907 Avondo donated the castle to the Italian State and, after the establishment of the regions with special statutes, in 1957 the latter passed to the Autonomous Region of Valle d’Aosta.

Issogne castle, despite the terrible state it was found in, was still considered a “sincere monument”. The centuries had passed over it “like the mists in the valley”. When Avondo purchased the building, he undertook a restoration that could be termed a simple repair and refresh (or as we say today “tender loving care”).

So as someone once wrote, Issogne is a castle “not spoiled by time, nor spoiled by men”. There can be no better description appended to a monument from our past.

The visit

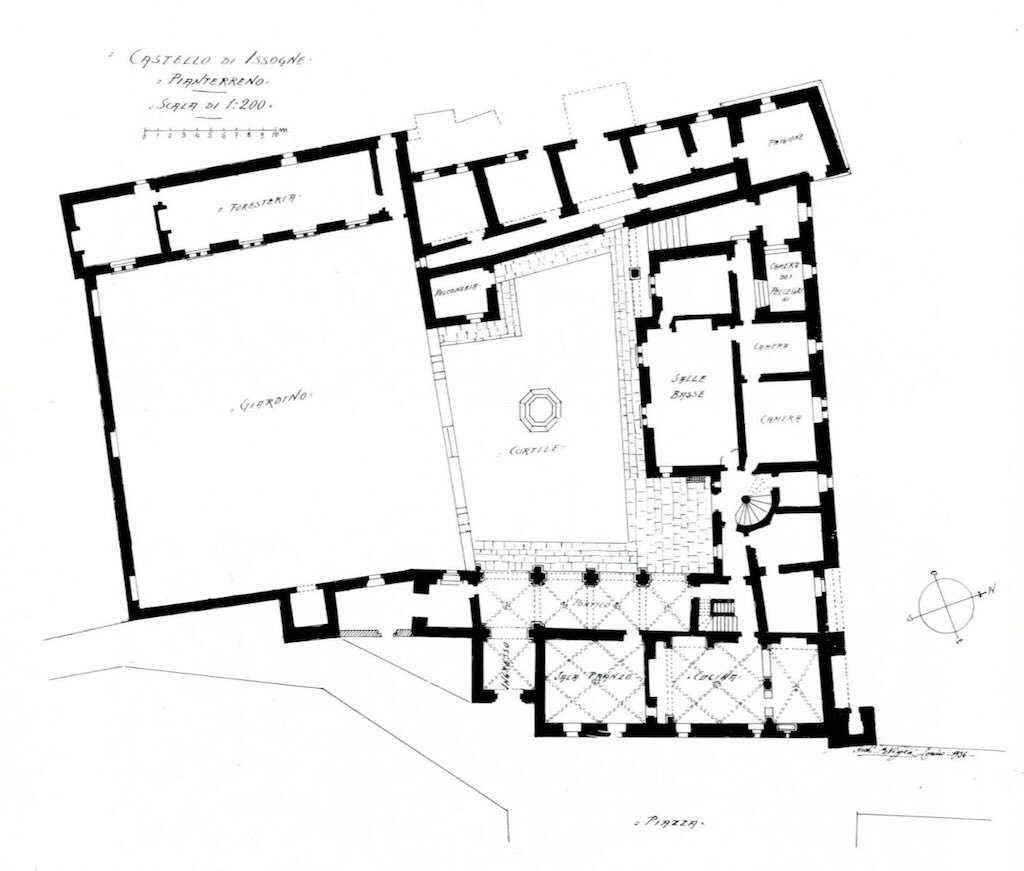

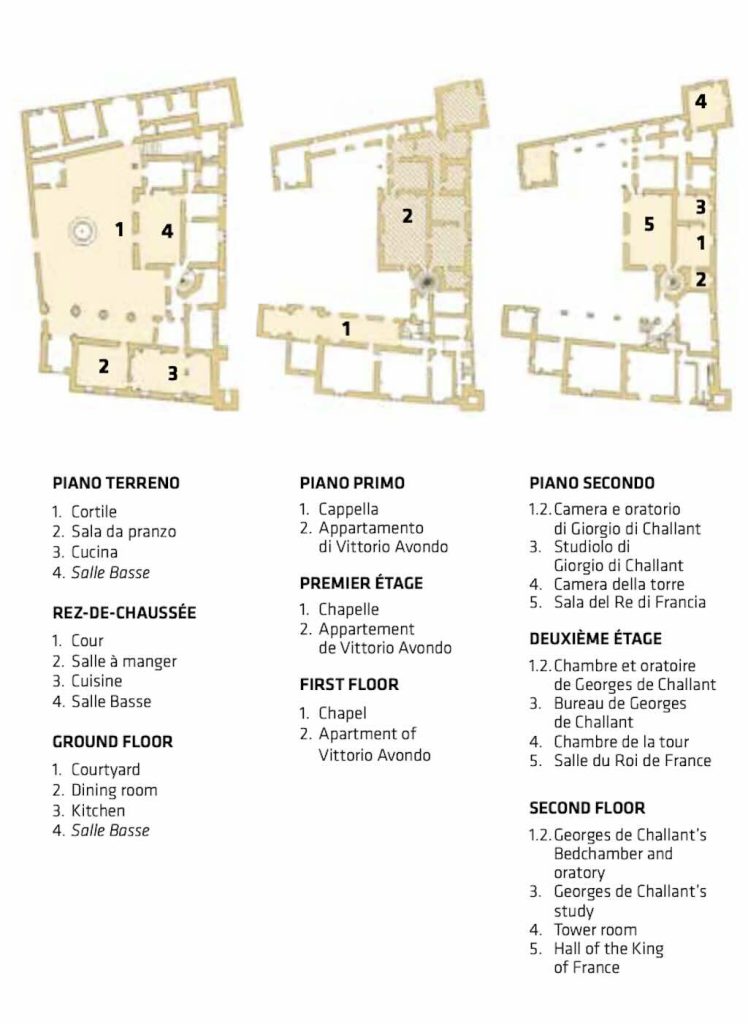

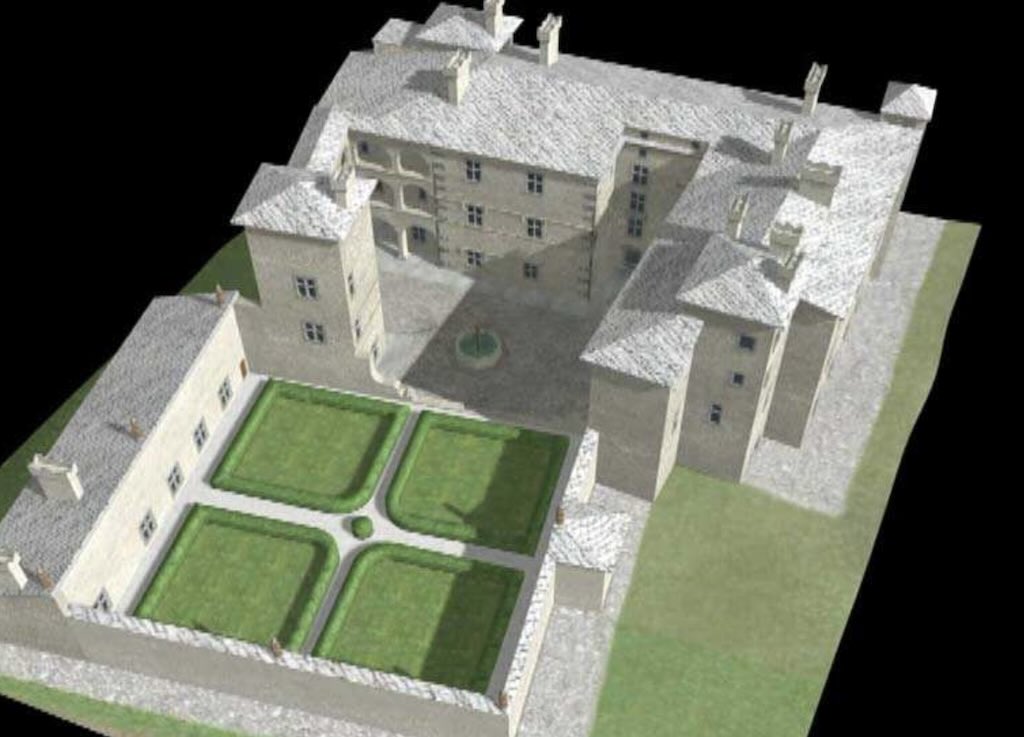

Above we have the castle (ground) floor plan from 1936, and it consists of three buildings enclosing a courtyard and a walled garden. The right-hand wall faces North, and the car park, and the West side is where the entrance is today. The two photos help visualise the courtyard and surrounding buildings.

And below we have the floor plans and rooms that are visited during the guided tour.

I don’t intend to describe the guided tour, but focus on just some of the more interesting decorative elements seen as we walked around.

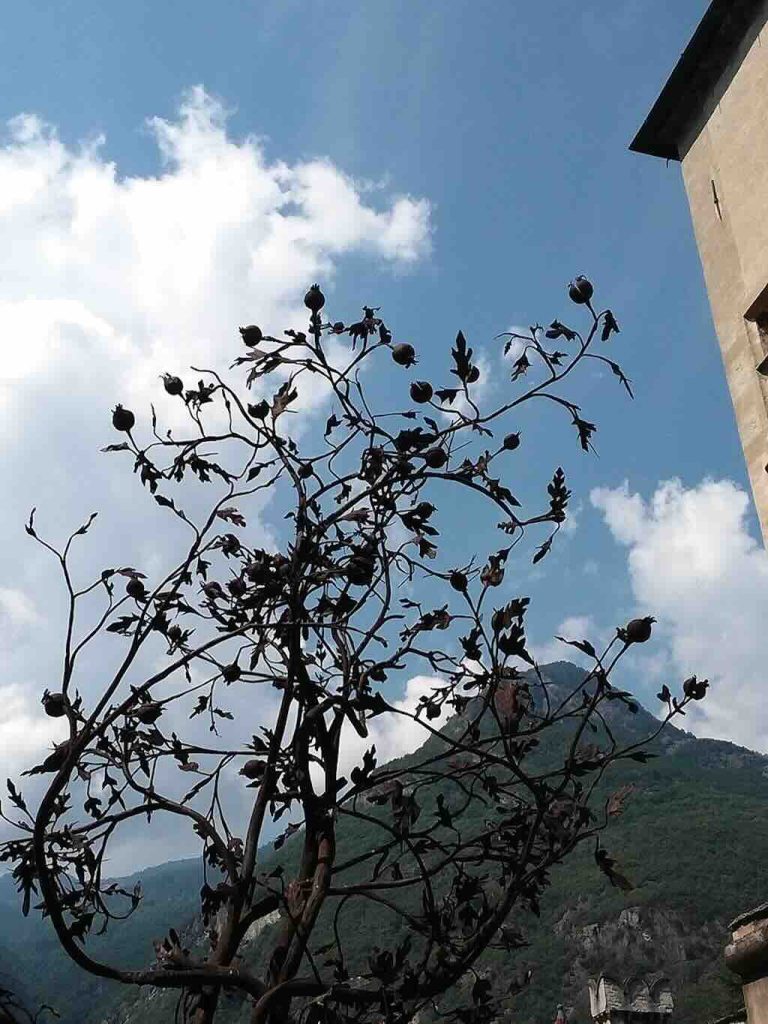

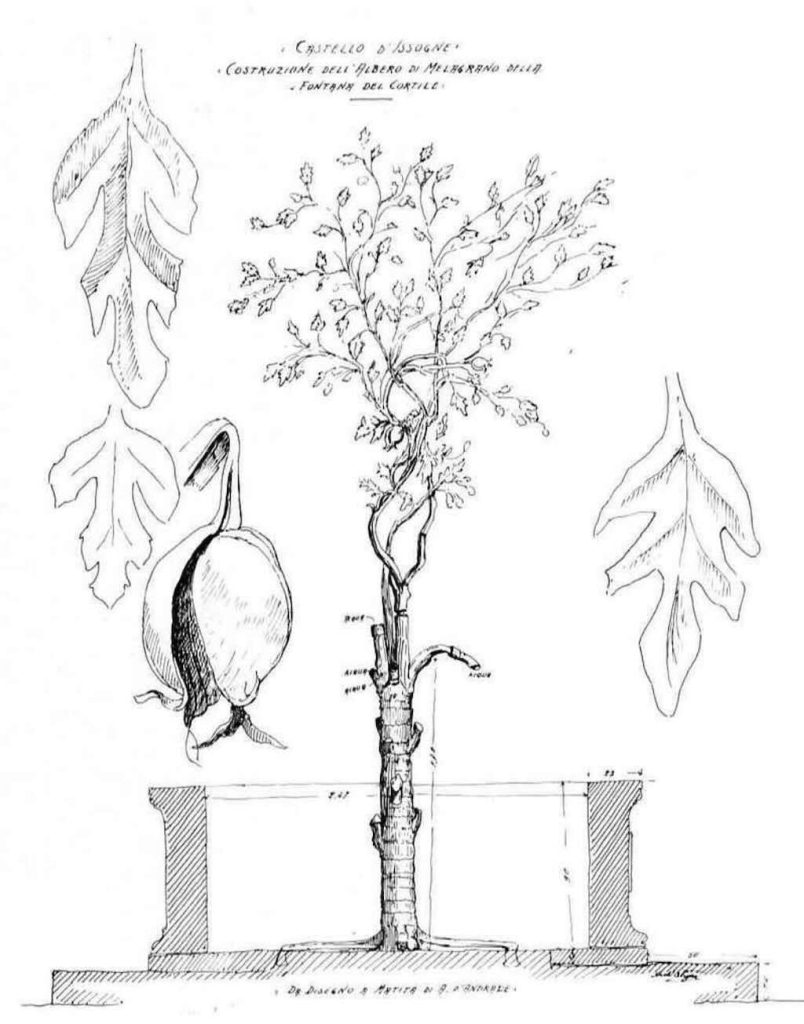

In the centre of the courtyard is the Issogne Pomegranate Fountain, created in the 16th century, perhaps as a wedding gift from Georges de Challant on the occasion of the marriage of his nephew Philibert to Louise d’Aarberg (Lady of Valangin, grand-daughter of Claude of Aarberg-Valangin). This would date the “tree” to around 1502.

The fountain in the shape of a tree is made of iron and at one time its trunk would have been gilded, while the oak leaves and pomegranate fruit were respectively green and red. It sits in the centre of a stone basin with the Challant coat of arms marked on the rim. It is both a fountain and a well, because it gushes fresh water brought there from the nearby mountains.

The pomegranate fruit is made up of two detached halves and the leaves are of different sizes but all marked with very noticeable folds and with strong chiselled ribs. The trunk is chiselled to imitate bark.

The fountain, a regular feature in Renaissance gardens, brought with it many symbolic elements and its presence contributed to the enchantment of an “Italian-style” garden, one with geometric spaces defined by hedges and water features. The pomegranate is often mentioned as a symbol of fertility and immortality, however, Renaissance artists like Fra Angelico (1395-1455) and Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) incorporated it into their religious paintings as a symbol of resurrection and immortality or redemption and salvation.

A faithful copy of the fountain, made for the General Exhibition in 1911, can be found today at the Borgo medievale in Turin. The fountain also figured on a 120 Lire Italian stamp in 1979.

In addition to the Pomegranate Fountain, the courtyard is home to a complex composition with more than 60 coats of arms of family relations on the walls of the main building. This was called the “Miroir pour les enfants de Ozallant” (a mirror for the children of…), and was intended almost as an “educational tool” to to keep alive the memory of the ancestors and to inspire emulation in future descendants.

During our visit these walls were partially obscured by scaffolding. There is an ongoing project of conservative restoration of the decorative plasterwork. The Challant family coat of arms is considered to be part of an invaluable historical and artistic heritage of the Aosta Valley in the 15th century. The project involves the consolidation of the painted film, the re-adhesion of the plasterwork to the masonry, the cleaning of the surfaces and the reintegration of the painted surfaces with the aim of preserving the painted depictions and coats of arms still present. This project started in 2022 and will finish in 2025, at a total cost of €3.25 million.

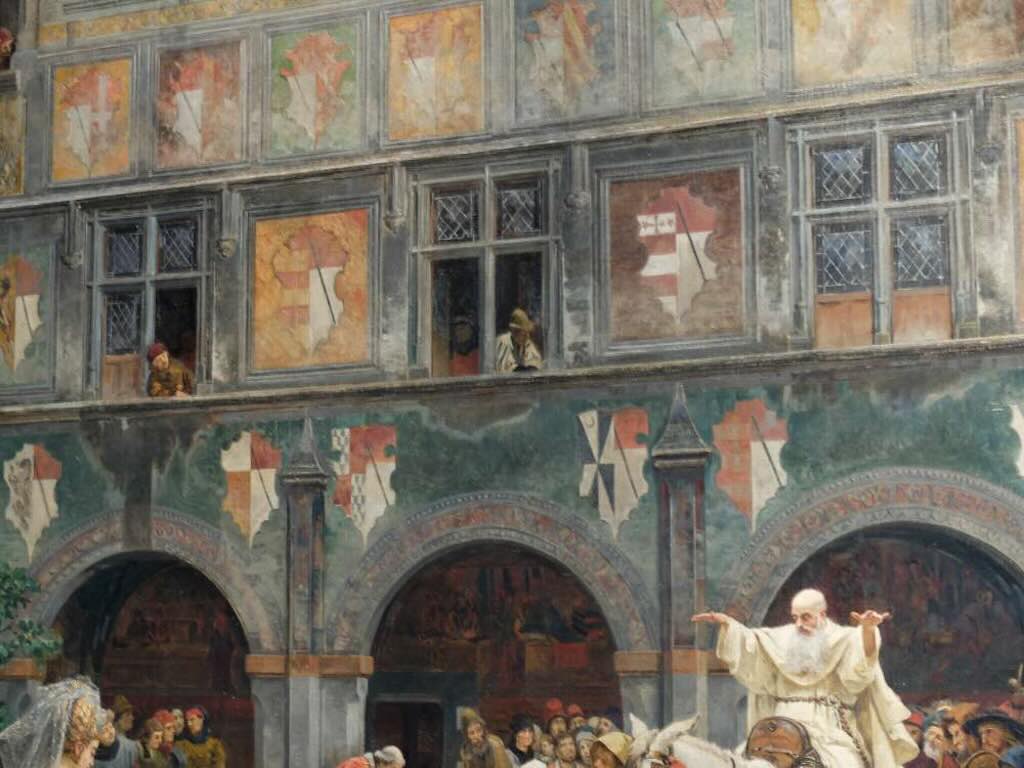

Vittorio Avondo who bought the castle in 1872, was an Italian antiquarian and painter. His painting “Ritorno di terra santa” (seen above) is thought to faithfully reproduce the wall decorations visible in the late 1800s, and this is being used by the restorers as a guide in their work. Of particular interest are the 32 matrimonial coats of arms of the family painted above the windows, since these have suffered the most over the last 150 years.

Millions of €’s is a far cry from the Italian state allocating 28,000 lira in 1937 to restore the paintings, arrange the orchard, clean the service rooms, renovate the other rooms, and restore the roof and copper gutters.

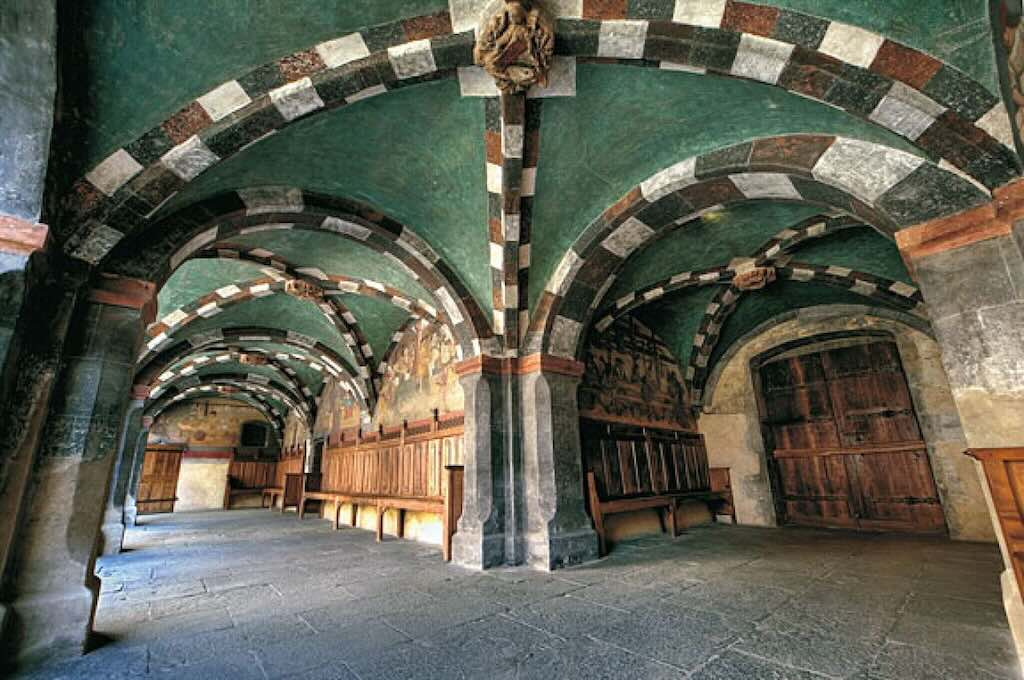

The lunettes (a half-moon–shaped architectural space) of the portico is home to lively scenes of everyday life in the village. The benches in the courtyard portico, decorated with the folded parchment motif characteristic of Franco-Alpine Gothic, are according to the original design known to have been employed in the castle in the 15th century (only the fretwork decoration is a 19th-century addition).

I understood that the roof of the portico had been slightly restored in one or two places, but was mostly original, and the scenes in the lunettes were original 15th century, and amazingly had not been restored. In the first photo we see the main entrance to the castle, which today overlooks the town square of Issogne (the visitors entrance is on the other side of the building).

Concerning the frescos seen below, I was told that they had not been restored had been cleaned.

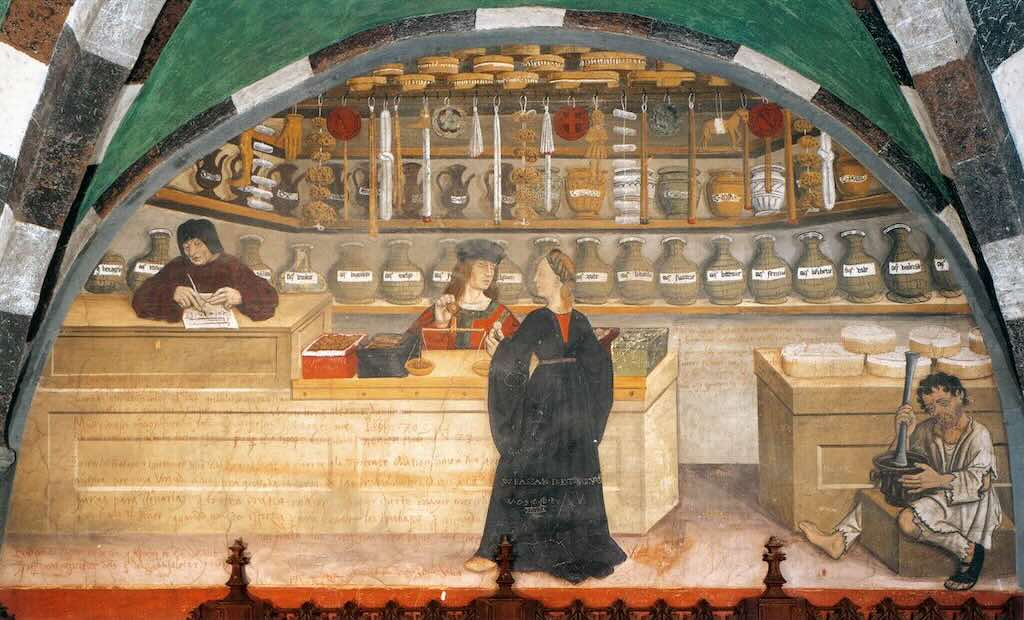

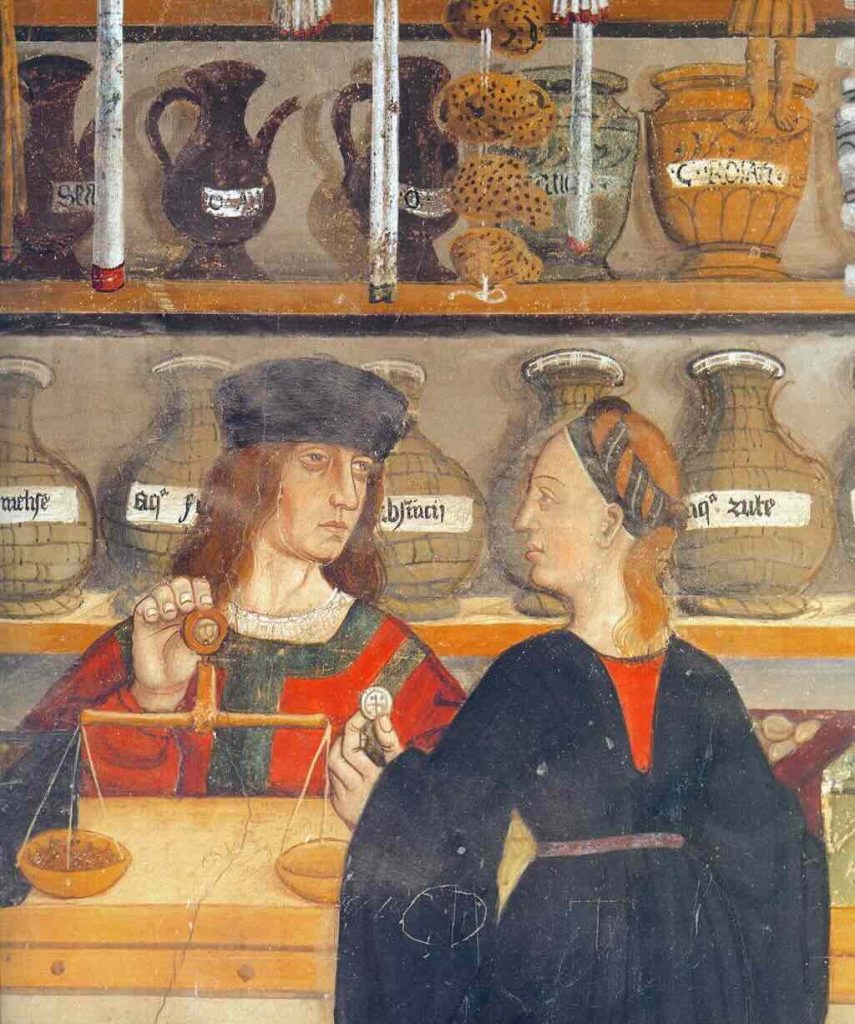

The guide confirmed that the content of the frescos were quite special, but no documents remain explaining why they were created. Depictions of quotidian activities are highly unusual for frescoes and normally only found in pictorial medieval calendars, known as “Labours of the Months”. My own little idea is that they may have been another kind of “education tool” for the young nobles living in the castle. Experts have offered a more complex, and possibly more compelling interpretation. One possibility is that the images of the guardhouse depict a brawl amidst gambling and drinking to illustrate examples of poorly conducted business, and that the orderly apothecary image shows how to appropriately manage a place of business. In some of the scenes women and men engage in inappropriate acts that include sexual innuendos with fruit, and overall the “chaotic” images seem to have a comedic or ironic tone. In contrast, the apothecary depicts order with labeled and organised vessels and an attendant bookkeeping. If these frescoes are morality lessons, then perhaps they are meant to demonstrate to broad audiences on how business in the marketplace should be conducted.

Today the frescoes are importance because they offer an insight into the history of clothing/costumes, and provide a glimpse of life at that time. The scenes, in which many characters wear the Challant livery (with the red, black and silver or white colours of the coat of arms) clearly are a kind of propaganda. But we have to remember that what we are seeing are the local bourgeoisie and servants of the nobles buying from the tradesmen, since nobles would never have lowered themselves to mix with the trades. Here the aim is to underline the climate of economic well-being and peaceful industriousness that was the result of a wise and enlightened government, i.e. a lord that protected his subjects from the dangers of war and harmoniously resolved social issues of the time. But nobles mixing with the lower classes, never!

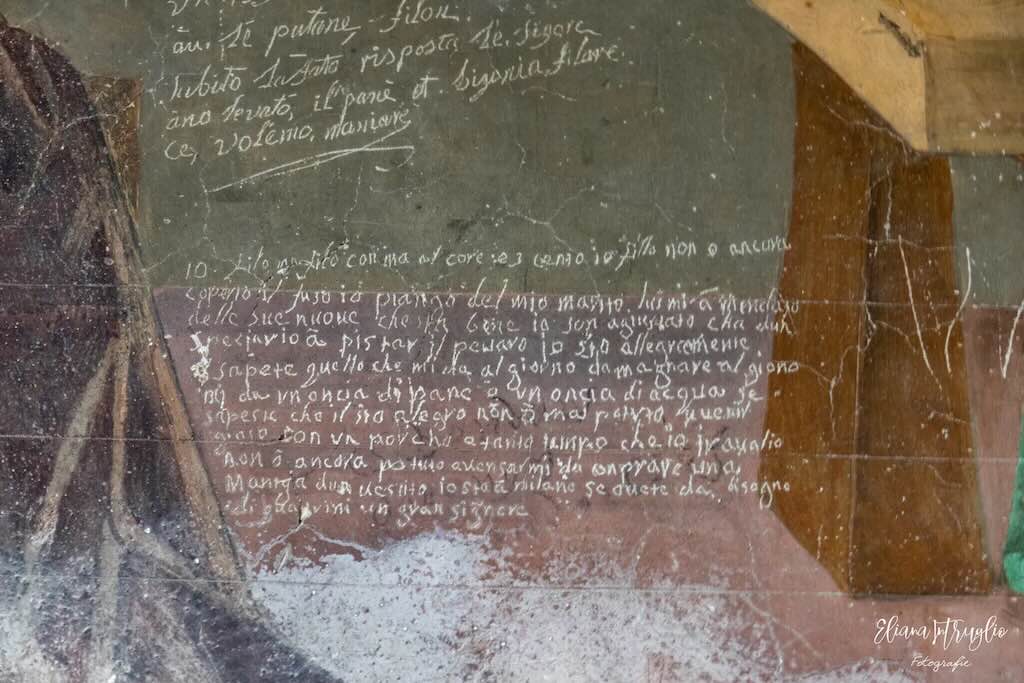

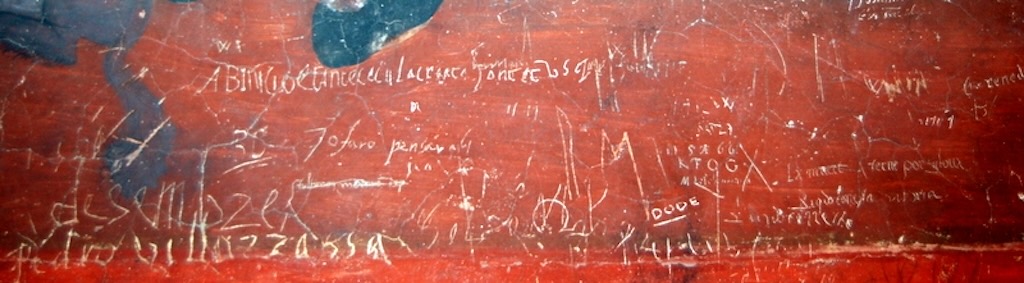

A large amount of graffiti can be seen on the paintings. These spontaneous inscriptions are present in all parts of the castle and cover a chronological period of several centuries, from the end of the 15th to the 19th century. While on the one hand a deplorable habit, they nevertheless provide a corpus of graffiti that today constitutes a precious testimony of the life of the castle, and occasionally of the private lives of its owners and guests. We will come back to this subject a little later in this post.

The below images are all taken from the Web Gallery of Art.

Naturally, next to the original main entrance, we have a fresco of the guardhouse, with weapons hanging on the rack. The soldiers are busy with their peacetime pastimes (cards, tic-tac-toe, etc.), and there appears to a discussion with a young woman on the complex issue of supply-and-demand.

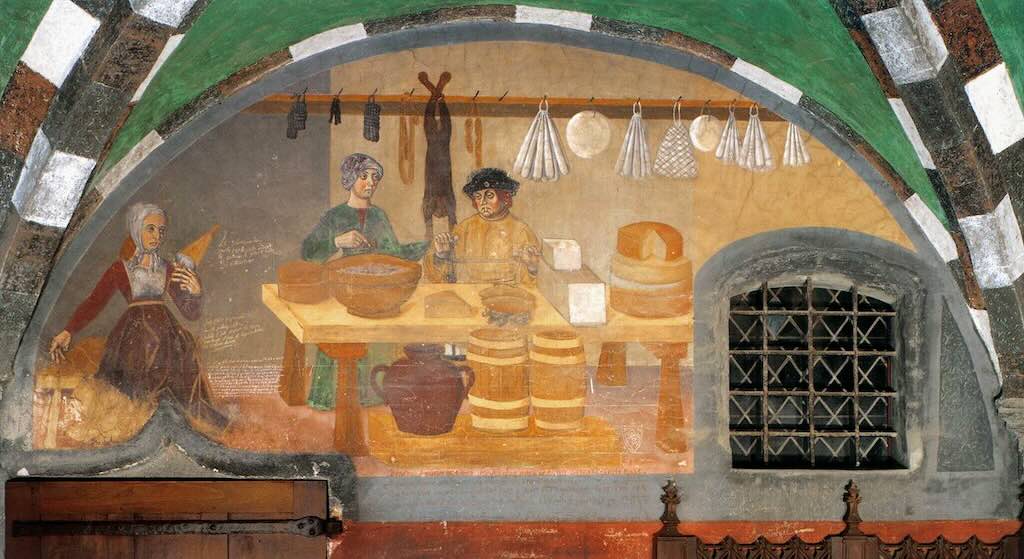

Next we have the butcher and the baker. On the left a boy is kneading the pastry, while the baker is baking what might just be an early form of meat pie. On the right the butcher is turning the spit, whilst a cat is approaching the plate of offal on the counter. In the background various meat are hanging, as are the tools of the butchers trade.

Now we have the open market, which in those days was a privilege granted by feudal lords to “his” people. We see various kinds of vegetables, and the more precious fruit displayed in beautiful order on the stalls. Customers and saleswomen discuss quantities and prices, whilst standing in front of the cobbler’s and haberdasher’s shops seen in the background.

Next comes the tailor’s shop, with two people measuring the fabrics neatly folded on the counter, a third cutting and a fourth sewing clothes. All set against fabrics and completed garments hung on a bar at the back.

No village would be complete without an apothecary’s shop. In the centre is a boy weighing a substance for the customer, who is offering a coin in payment. On the left the apothecary is intent on drawing up his accounts, whilst on the right is a poor man, dressed in rags, pounds spices in the mortar (a pestapepe). On the shelves behind the counter are beautifully displayed vases of medicinal herbs, wax votive offerings of anthropomorphic shapes, sea sponges, etc. Note here the sharp differentiation of social classes, with the chemist, a representative of the nascent bourgeoisie, clearly a cultured and well-off man, who, naturally, limits himself to keeping the accounts of his shop. It is the apprentice who serves customers at the counter, whilst the lowest rank in the social hierarchy, represented by the beggar, is occupied performing very simple manual work.

Last, but not least, we see the “dry goods” store with its cheeses and sausages. Here we see blocks of butter, cheeses, sausages, ropes, bunches of candles, a large cup-shaped vase, a terracotta jar and barrels. In the centre the shopkeeper weighs the goods under the attentive eye of the customer, and to the side a woman is intent on spinning.

Still on the ground floor we visited the dining room and adjacent kitchen. The door to the dining room is in the portico, and access to the kitchen is through the dining room. In fact the kitchen is divided into two parts, one where the master would eat (above photo) when he was not entertaining visitors in the dining room, and a second part for the servants.

The vaulted ceiling with its stone ribs is original, as are the three large, fully equipped fireplaces.

Sala d'Onore

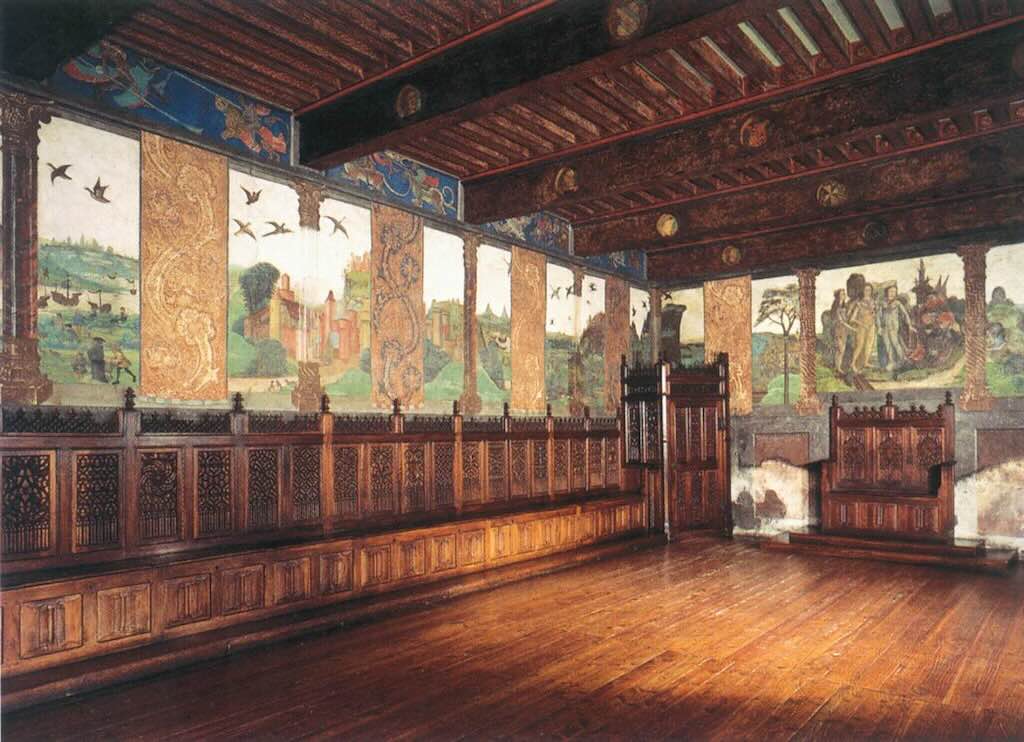

Also on the ground floor there is the “Sala d’Onore” (Hall of Honour) also called “Salle Basse“. I’ve seen this room also called “Sala de Giustizia” and “Sala Baronale“, so I guess it would also have been used as a courtroom. In any case it was clearly designed to impress guests, visitors, and presumably those waiting for judgement.

The “Salle Basse” presents a continuous decoration on three walls, and the originals of the carved wooden stalls are now in a museum in Turin. The ceiling is made of painted beams and joists and on the back wall there is a large and beautiful monumental stone fireplace surmounted by the Challant coat of arms flanked by a griffin and a lion. Over time the griffin became a Christian symbol of divine power and a guardian of the divine, and was usually portrayed with the rear body of a lion, an eagle’s head with erect ears, a feathered breast, and the forelegs of an eagle, including claws.

The wall paintings depict a continuous loggia supported by columns of crystal, alabaster and variegated marble, interspersed with painted sheets representing precious patterned fabric as if hanging from the architrave. The use of cloth drapes for decorative purposes in the furnishings, as these 15th-century painting depict, was very widespread at the time. In winter tapestries would often be hung over these fabric panels, in order to try to retain the heat in the room, and keep the cold wind out.

Beyond the loggia opens up a vast landscape with woods, inhabited centres (Verrès castle and a view of Jerusalem with the Calvary are recognisable), scattered architecture, waterways where boats sail. Everywhere there are people intent on various activities (lumberjacks chopping wood, hunters, people gathering wild fruits of the forest, wayfarers, etc.).

On the far wall is depicted the Judgement of Paris, according to an iconographic tradition spread beyond the Alps that saw Paris dressed as a warrior and not as a shepherd.

Stylistically, the master who executed these frescoes was familiar with Flemish culture which permeated the pictorial language of the 15th century, north of the Alps. Characteristics of the Flemish school are the extreme realism of the details and the careful description of the environments and landscapes. Certain iconographic details of the frescoes (sloping roofs, “half-timbered” architecture next to the Judgement of Paris, a mill) also refer to the Nordic environment. The upper band of the walls of the room features a fantastic decoration with both exotic and mythological animals.

The Cappella

The frescoes of the chapel (although altered by later repaintings), and the paintings of the doors of the polyptych (on the childhood of Christ) can be attributed to the same master active in the lunettes of the portico, and again in the Flemish inspired transalpine style.

The chapel is divided into five sections by arches and cross vaults on ribs richly decorated at their keystones with gilded and painted Challant coats of arms. A wooden gate, of simple but elegant design, divides the part reserved for the lords from that intended for the servants. The altar is adorned with a Flemish triptych and its front is carved with openwork on a coloured background.

During our visit, the two door panels of the altar had been removed for restoration.

I’m not going to extend the description to all the other rooms accessible in the castle, but I do want to mention the spiral staircase, and the graffiti.

The spiral staircase

I’ve always been impressed by spiral staircases, and here we have a stone spiral staircase, a characteristic typology of French architecture but also traditionally present in the Aosta Valley. Remember this spiral staircase was designed and cut in the late 15th century.

This particular staircase is a masterpiece of technical skill and a splendid example of an elegant design. In essence, the steps are cut in single pieces of stone. The shape, like the steps of any spiral staircase, are a sector of a circular crown, with a thickness equivalent to the height of the step, but in their thinnest part they terminate with a cylindrical element. The overlapping of the steps involves the vertical alignment of these cylindrical elements, as if they were small drums. In this way the central support column is formed, while the steps fan out to create the stairs, each overlapping the other and fitting into the surrounding masonry to improve the stability of the overall structure. The suggestive effect of the staircase is completed by the ceiling in the form of a smooth continuous ramp.

In addition the stairs join perfectly the floors despite them being of differing heights. And this is done by inserting a few steps of a slightly different height. If one looks carefully, there are the occasional double step cut from one piece of stone, that performs this function.

The graffiti of Issogne

What we call graffiti certainly already existed in Roman times. Almost every free wall showed written traces of the passage of soldiers, pilgrims, and even customers in the case of inns and hostels. They would leave proverbs, names and dates, sometimes adages and quotes from the Holy Scriptures, or just news about the life of the local community, and of course comments on the great events of history. Over time most were erased by bad weather or by the redevelopment of buildings.

Their remarkable presence in the Aosta Valley is due to the fact that often building, etc. were handed down over the centuries without having undergone major changes. The decadence of the local nobility following the transfer of the capital of the Duchy of Aosta from Chambéry to Turin and the poverty of the communities, decimated in 1630 by the plague and debt meant that medieval sites were never converted to the later baroque and neoclassical styles.

Issogne is said to be home to more than 2,000 examples of graffiti, yet the surfaces of its walls still date back to the 15th century. This is because the château, while never having been abandoned, was replaced as the main seat of the owner families by other residences, already from the beginning of the 17th century. This fortunately protected the building from the risk of major architectural transformations.

The non-religious nature of a lot of the frescos and the inclusion of text along with the coats of arms, may have seduced people to leave a mark of their passage on the walls, if only their name and the date. In most cases, the inscriptions were engraved using a metal drypoint, in more or less deep incisions depending on the use of the tool (pin, nail, knife point, etc.). Sometimes oil pastels were used, in a red colour like sanguine or brown, which allowed for more elegant and cursive writing.

Alongside Latin, which is used mainly for the oldest or most solemn inscriptions, as time progressed, local languages, particularly French, but also Italian, appeared more frequently. The presence in the castle of Countess Mencie of Portugal, trained at the Spanish court of Emperor Charles V, explains the fact that some graffiti, dating back mainly to the middle of the 15th century, are written in Iberian languages. The few inscriptions in German are also justified by the visits of Tyrolean friends to the successors of Count René of Challant.

The oldest graffiti in Issogne leaves us the names of artists and workers who worked for Georges de Challant, such as the master painters Colin and Étienne or the mason Jean de Valupe, as we can clearly read on the pillar of one of the arcades of the courtyard, “1489 Jan de Valupe built the cellar of this castle for 20 florins”. This stonemason does not appear in the castles accounts, but the date 1489 has been used to suggest that the building was well on its way to being finished by 1502 (or at least by 1506).

Heartbreaks and disappointment abound, for example “I’m sorry, trust no-one, Maledictus homo, who trusts in man” (reference to Jeremiah 17:5). However, the life of past centuries was not just occupied by prayer, contrition and sadness. Opportunities for relaxation and jokes were available even to the lower classes, and they were perfectly happy to add the odd insult to a wall here and there.

The marketplace, shown in the frescos, was an everyday place associated with the lower classes so it may also indicate how lower classes were viewed in 15th-century society. The graffiti that appears on the frescoes comment on the episodes depicted in the frescoes. Some of remarks discuss members of the lowest classes such as beggars, spinners, and prostitutes. But equally comments were also addressed to the trades, with “Ladri sono i sarti” (Tailors are thieves), which appears in the tailor shop, and “Chi serve li signori more al ospidale” (He who serves the lords dies in hospital), which is found in the salami-cheese shop scene.

Our poor pestapepe in the apothecary shop, was doing a task that was given to the poor as an act of charity. So naturally he attracted his fair share of graffiti, with pista o poltron, lazy man or coward, and pesta gozzo, where pesta means pound or crush, and gozzo is defined as meaning the medical term “goiter”, or a number of other definitions, all with negative connotations. We can say that our pestapepe really “gets it in the neck” in more ways than one, but he also attracted an inscription that read In stato tal non mi lasciar morir (In such a state do not let me die). Interestingly, graffiti often appears across the body of the poor, whilst is placed around the body of the more urban elite.

The female figures in the frescoes acquire a large amount of graffiti. There are a number of women spinners (filatrica) in the different frescoes, and most of the comments are less than complimentary. Figures holding distaffs or spindles were generally seen as respectable and diligent housewives. So naturally some of the graffiti suggesting that spinners is another name for prostitutes, and there is even a suggestion that one of them is the wife of the pestapepe. This link between spinners and ladies of ill repute is nothing new, since it dates back to Roman times.

Records of visits to the castle, which frequently include names and locations written in a multitude of languages, predominantly French, comprise large quantities of the graffiti found inside the castle rooms, as opposed to the courtyard. It is more or less evident that graffiti was an informal, but systemised way for a guest to leave a record of their visit. This signature process supports the theory that graffiti-making was a kind of ritual act, repeated over a long period of time. Many of these examples indicate loyalty or affiliation with a ruling family, or to a specific location, through the use of Latin “VV”. This “VV” is an abbreviation of the Latin verb “vivat,” which means “long live…” (or the Italian viva) and referred to whoever was named in the inscription.

This last graffito below clearly shows that cutting a message into the castle wall was not something done quickly and “on the quite”, but was a well-respected (or at least well accepted) social gesture that might have taken several minutes to perfect.

A little bit of history

The castle of Issogne appears today as a homogeneous architectural monument, as if it was built and decorated by its original owner, but there are small structural differences that actually point to a building that has evolved over the centuries.

Most of the architectural and artistic elements date from between the 15th and 16th centuries, but there are pointers to the fact that there was a very explicit attempt to hide some more ancient features. This was a challenge to those who would later restore the castle (see the photo below dated to sometime after 1910), and suggests that some elements of the original building had been removed. As someone pointed out, restoration was like working on an “archaeology of absence”.

Firstly, static structural elements that are now missing or have been added later need to be identified, which is not easy since the build tries to conceal these changes by presenting a uniform structural and decorative facade. Then there is an analysis of how the building would have been used at different times, and this goes right down to examining the “wear and tear” visible and absent in different parts of the building. In some ways the archaeologist is not just looking at what is there, but also what is not there (the “faint traces of the non-existent”).

We have to remember that the photo below was taken some considerable time after a major “restoration” made by the then owner in the 19th century.

This kind of discussion might appear a little academic, but it actually affects how we look at the history of this building.

By looking beyond the superficial appears of a building dating to the middle-ages, in 1972-73 they discovered that the structure dates back to the Roman era. A Roman presence had been suggested by various local historians based upon the existence of two funerary inscriptions. However during a cleaning intervention in the cellar rooms in the main body of the east wing they found a series of Roman structures in opus incertum, an ancient Roman construction technique.

Further work involving the entire building of the east wing and a portion of the current garden confirmed the existence of a settlement that was more extensive than what had been suggested in the past. The reality of the work of an archaeologist is highlighted by that fact that the original settlement plan is incomplete because the castle cellars go down through the Roman walls and the surrounding walls of the most ancient phases of the medieval fortification sit on top of them. In addition modern piping has been installed, and parts of the original Roman walls have simply been removed as waste.

Today the Roman settlement of Issogne is seen as an explicit manifestation, within a large program of colonisation of the territory during the Augustan era, of land surveyed and assigned (ager divisus et adsignatus). The result was probably a typical subalpine and alpine settlement of the time, i.e. possible a single-family farm rather than a residential villa.

One interesting suggestion is that because of the perfect overlap between the Roman structures and the medieval building its possible that there may have been continuity of settlement between the two eras.

The first mention of Issogne is in a papal bull sent by the Apostolic See to the Bishop of Aosta, attributable to Pope Eugene III and dated 15 January 1151. Some authors attests to the existence of an already defined power of the bishop over the locality, but others think that the origin of the episcopal jurisdiction can only be traced back to an act of generosity carried out in 1227 by Count Thomas I of Savoy.

However, already in 1209 all rights held in the parish of Issogne by a certain Odon, probably lord of Arnad, as feudal lord of the Count of Savoy, were ceded to the ecclesia Sancte Marie (and thus to the Bishop of Aosta).

As already mentioned it’s probable that a settlement persisted on the site from Roman times. Recent excavations in areas bordering the Aosta Valley territory have highlighted the existence, in the late-ancient settlements, of private Christian oratories, chapels and churches, built and financed by the owners of the agricultural lands and the related rural villae. This would support the idea that a similar situation prevailed also for Issogne. So the idea is that initially the site was a private oratory which over time also came to fulfil a “public” function for the celebration of Sunday mass for the benefit of the inhabitants of a vast rural area around the site.

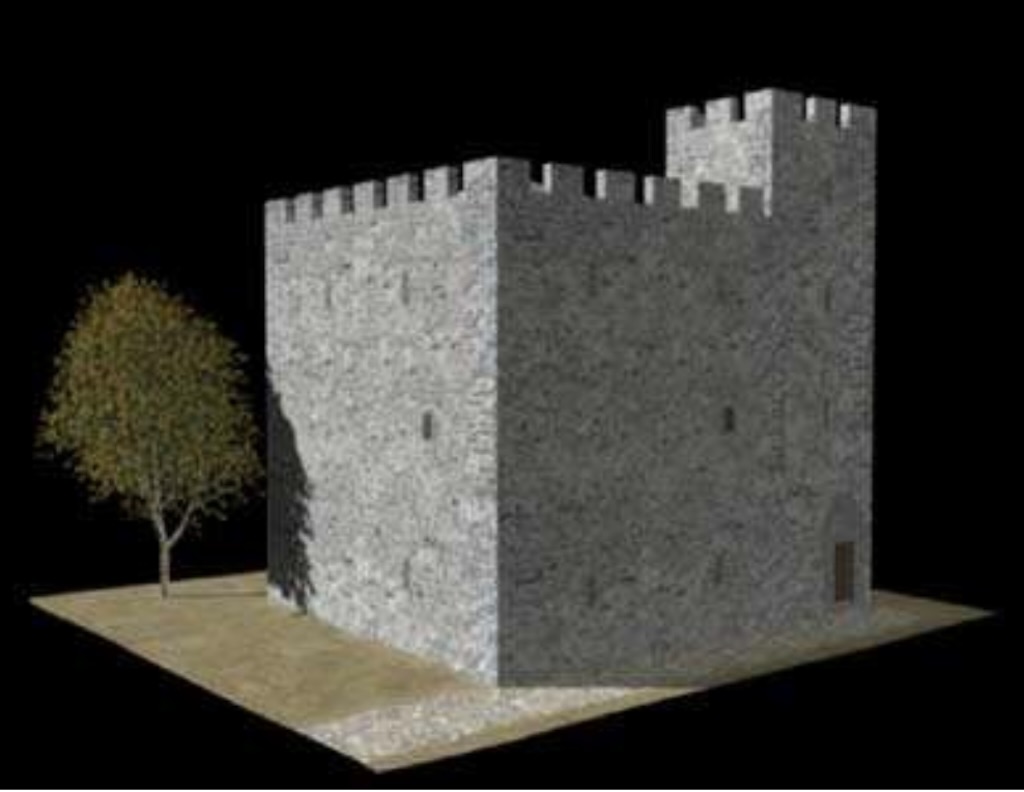

The idea is that along with the continuous clearing and planting of new farm land came a political structures that included minor elites dominating those spaces and building stone residences. It is precisely from the 12th century that the construction of towers or fortified buildings, such as this domus episcopalis, started. Alongside this episcopal intervention, a conspicuous quantity of small aristocratic elites, not completely free from any vassalage, attempted to consolidate a limited territorial supremacy. So small landowners express their rivalries and their status by building towers on the plateaus they owned and exploited.

The possession of a landed estate allowed the owners to exercise authority over subordinates who worked in that territory, and at the same time allowed them to accumulate assets. The owners constructed buildings that came to have juridical-institutional importance, and at the same time were manifestations of prestige. So it’s again not surprising that hamlets and villages grew up around these stone buildings. They were centres of power capable of guaranteeing income and protection.

The best estimate is that initially there was a parallelepiped block of about thirteen meters on each side that perfectly respecting the alignment of the original Roman structures. This building must have been made up of a large room, or hall, which occupied more than half of the internal surface, along with other rooms of modest dimensions. The height is unknown, but a comparisons with other similar structures suggests at least three or four floors above ground. It’s possible that a tower also existed, because it’s mentioned in 13th and 14th century documents. However, it’s also possible a four-floor main building might have been considered a tower in itself. And equally possible a tower might have been built later as an extension on the roof of the original building. It is still not known where the chapel mentioned in the mid-12th century was situated (the suggestion that it was in the extreme south-east corner, is simply based on the presence of a fresco on the east-facing wall of the bell tower). Also the papal bull mentions castrum (fortified), so an explicit intent to fortify the building. But it’s not clear if this was to fortify the building itself or to add fortifications to (around) the building. Despite the uncertainties the conclusion is that this type of building was designed as a precise affirmation of superiority and power.

Among the various episcopal figures who had the opportunity to occupy and manage the domus of Issogne, Nicolas II Bersatoribus undoubtedly stands out, because the vicissitudes and events in which he was involved were decisive for the radical transformation of the building.

Of the twenty-one bishops who held the chair between 1151, the date of the first mention of the domus episcopalis, and 1379, the moment in which the jurisdiction of Issogne was enfeoffed to Ibleto di Challant (Yblet de Challant in French), Nicolas II Bersatoribus was the one who had the longest mandate, thirty-four years, which probably allowed him to intervene the most in the political and structural choices that concerned the entire building. He modified the residential and ostentatious character of the building, making it into a structure with distinctive fortification elements (see above). In fact, the documents only speak from this moment of a merlata et curtinata (battlements) structure, confirming that its previous appearance must have been of much simpler.

Judging from documents covering the possessions and transfers of ownership, for the entire period between the second half of the 13th century and the first half of the 14th century, the episcopal ownership of the fortified house was not without its problems. There was a constant dispute over ownership between the bishops and the lords of Verrès (see the château de Verrès just across the valley). It looks like a certain Aymonet de Verrès occupied the castle in 1333-34 accusing the bishop of having equipped the tower with battlements and surrounded it with walls without his permission. It was only on 8 March 1334, Aimone di Savoia ordered the bailiff of the Aosta Valley to force Aymonet de Verrès to return the building to the bishop. It seems, however, that at this point the bishop did not return to live there and the entire complex was neglected and left to slowly decline, perhaps precisely because of the serious damage suffered during the siege.

It’s not clear what was destroyed and what was rebuilt, but by the first thirty years of the 14th century the domus seems to have slowly (re)acquired the appearance of a real castle. The situation is confused by the extent of the Roman era terracing structure, and the later work of Georges de Challant. He would give the wall structure a dual function of terracing wall and building wall. The wall on the entire north side was built next to a moat or canal, which still exists and functions today. And Ibleto de Challant had the latrines built in a corner tower right above the moat.

The fate of the castle changed definitively when the bishop Giacomo Ferrandini decided, on 15 June 1379, to enfeoff the jurisdiction of Issogne, with the fortified house and the rights annexed, to the knight Ibleto de Challant. The documents appear to confirm that (by then) there were two architecturally distinct elements, the fortified house and the tower. Furthermore, at the time of the investiture of the lordship, a clause is cited with which the bishop reserved the use of the prisons that were located under the fortified house.

So Ibleto (Yblet) de Challant’s took possession of a very degraded site, and in fact he would, until 1390, focus on redeveloping the castle of Verrès. He would then turn his attention to the castle of Issogne between 1390 and 1402, when he ceded the lordship to Marguerite de Challant. Whilst not a culturally significant topic, it’s worth noting that the construction of the latrine tower was a major innovation. It exploited a canal (that still flows in the same place today) to dispose of sewage. The approach was certainly avant-gardist because it externalised and isolated the latrines from the living rooms. The attention paid to this topic inside the castle demonstrates on the one hand a precise need for hygiene, something relatively unusual for the time, and at the same time the degree of importance that was assigned to it by dedicating an entire building. The new owner created a new entrance, added two large arches, a new block of rooms on the south side, two large rooms with an entrance hall and a tower, and a portico on the courtyard. This building must have been at least two floors high, but certainly did not reach its current height.

Georges de Challant (1440-1509) has always been seen as trying to skilfully connect existing buildings. The prior’s intention must have been to create a single palace with an apparently uniform style. The castle had already taken on the residential characteristics of a stately home, and was no longer a fortification. The choice of materials was careful and scrupulous with the precise intent to adapt and harmonise what already existed. This included a complete coherence in the plasters used, etc., and the final result was of such high quality that it has remained almost totally intact to the present day.

But this was not a simple “paint-job”. It included the construction of the loggia with the creation of the chapel and the raising of a floor of the entire building on southern side. The decoration, despite its extraordinary quality, has hidden any traces of the older openings. The latrine tower was connected to the main building, and the simple perimeter wall disappeared and a loggia was created. Another large-scale intervention was the demolition of another part of the perimeter wall and the creation of the large garden with its hall, otherwise known as the “Camerone degli uomini d’arme” (I guess a “changing room” for the men-at-arms).

Another addition of considerable importance was the creation of the double connecting loggia, with the arches linking the old domus episcopalis to the newer building. And now the loggia provided access to the “Camera della Contessina Jolanda” (Chamber of the Countess Jolanda, but “Contessina” specifically refers to the daughter of a Count).

References

Mauro Cortelazzo and Renato Perinetti, “L’evoluzione del castello di Issogne prima di Georges de Challant“

Frescoes in Castello Challant – Web Gallery of Art

Sandra Barberi, “Il Castello di Issogne“

Sandra Barberi and Paola Elena Boccalatte, “Misure di Conservazione al Castello di Issogne“

Omar Borettaz, “Les Graffiti dans les Eglises et les Châteaux Valdôtains“