Introduction

It was immediately obvious that their physical dimensions and architectural choices reflect divergent priorities. Ocean Explorer is a robust expedition ship designed for high-latitude, ice-prone regions. Whereas Le Lyrial is more an elegant multi-functional coastal cruise ship with limited polar capability.

In fact, Ocean Explorer was purpose-built for polar and remote-region expedition cruising, with a strong emphasis on ice capability, scientific/explorer support, and environmental sustainability. It is marketed as a “next-generation expedition ship”, capable of year-round operations in harsh environments. For example, it features a X-Bow® hull, Polar Class 6 certification, and a mudroom. And hidden below decks there is reinforced hull plating under the waterline, heated tanks and piping, and ice radar integration.

Le Lyrial, by comparison, was designed as a luxury exploration yacht, intended to provide a “private yacht” experience. Though equipped for light expedition cruising (notably in Antarctica), the ship was not originally marketed as a full expedition platform.

The difference is obvious in the way each ship markets itself. Ocean Explorer is a “small rugged” explorer vessel with fuel-efficient engines, an ice-class wave-piercing hull design, and advanced waste gasification which underlines their “eco‑responsibility”. Le Lyrial is a “comfortable luxury” explorer with LED lighting, is low‑noise vibration “Comfort Class” compliant, and claims sustainability credentials (#1 by NABU).

Despite Ocean Explorer being built in 2021 (Le Lyrial dates from 2015), it actually felt the older of the two. Quark of course stresses its “timeless, functional design” and prioritising durability, operability in harsh conditions, seamless viewing, and “engineered to enhance polar exploration without compromise”.

Who built what?

Ocean Explorer was constructed by China Merchants Heavy Industry (CMHI) at its shipyard in Haimen, Jiangsu Province, China. This ship is part of the Infinity-class series, designed in cooperation with SunStone Ships and the Norwegian marine architecture firm Ulstein Design & Solutions.

China Merchants Heavy Industry (CMHI) is one of China’s largest shipbuilding and offshore engineering enterprises, capable of constructing everything from small specialized vessels to ultra-large offshore platforms and deep-sea ships.

Ocean Explorer was completed in 2021 and reflects post-2020 design priorities, including low-emission technologies and strengthened polar performance.

Le Lyrial was built in Italy by Fincantieri at its Ancona shipyard, a well-known builder of luxury cruise vessels. It is the fourth and final vessel in Ponant’s Boreal-class series, which includes Le Boréal, L’Austral, Le Lyrial and Le Soléal.

Fincantieri is one of the world’s largest and oldest shipbuilding groups, headquartered in Italy, building everything from small naval patrol boats to massive cruise liners and complex military vessels.

Le Lyrial was launched in April 2015 and represents Ponant’s pre-expedition-pivot era, prioritising elegance and yacht-like cruising over full expedition functionality.

Who owns what?

Quark Expeditions was founded in 1991 by explorers Mike McDowell and Lars Wikander, who initially organised small-ship dive trips before pivoting to polar expeditions, with the first tourist transit of the Northeast Passage, and the first consumer expedition to the North Pole. In 1998 McDowell sold his interest to Wikander, who became majority owner. In 2007 Quark was acquired by TUI Travel, and in 2016 it became part of Travelopia, a new specialist travel group spun off from TUI AG.

Travelopia (registered in Surbiton, England) is a specialist travel group comprising multiple brands offering curated experiences (e.g. polar expeditions, wildlife safaris, cultural tours, yachting, sailing adventures, etc.). Originally spun off from TUI, in early 2017, it was acquired by private equity firm KKR for approximately €380–407 million. In 2016 Travelopia had a turnover of ~€1.2 billion, post-acquisition figures aren’t publicly disclosed (2024 total employees 2,500-3,000). The German-based TUI Group is the world’s largest integrated tourism operator (2024 revenue €23.17 billion, employing ~67,000).

US-based KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. Inc.) pioneered leveraged buyouts and is one the world’s largest private equity firms. In 2024 total assets under management was $637.6 billion, revenue $21.88 billion, net income $3.076 billion (total employees ~5,000). For comparison, the conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway has consolidated total assets of $1.1539 trillion, and employs ~400,000 people worldwide.

It’s often quoted that Ocean Explorer is owned by SunStone Ships Inc., a Danish-American ship leasing company based in Miami. This is strictly speaking, not true. Again it’s also mentioned that they design, finance, and own expedition vessels, often built in China (e.g. Ulstein-designed Infinity class) and lease them via time-charter contracts. Again this is only partially true.

SunStone was founded in 1990 in Denmark by Niels-Erik Lund, and initially operated passenger ferries and larger cruise ships. In 2003, the group pivoted to focus on expedition cruising. By 2012, it had shifted to exclusively providing tonnage (vessels on charter) to expedition cruise operators. It’s often mentioned that they “now designs, builds, technically manages, and charters purpose-built vessels for polar and warm-water expeditions”. Note that ownership is not mentioned. The overall parent entity, SunStone Maritime Group A/S, is headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark, and there is SunStone Holdings and Ship Management based in Madeira, and US-based SunStone Ships, Inc. in Miami which manage vessel charters and technical operations. Total assets of the parent company in 2023 was $38.91 million, but with subsidiaries holding tangible assets of $118.5 million (land, buildings, machinery, ships). Total employment estimated at less than 200 people. Immediately we can see that the company cannot be owner of a fleet of explorer ships (each ship costs in excess of $60 million).

In fact SunStone does not own its ships outright, it is a tonnage provider, not a vessel owner in the traditional sense. SunStone charters vessels under long-term bareboat or time-charter contracts to expedition cruise operators (it’s really sub-chartering). SunStone designs the ships, and they are built and financed by Chinese state-owned shipyards like China Merchants Heavy Industry (CMHI). Once built the ships are owned by special purpose entities (SPEs) or leased through Chinese leasing groups. SunStone then manages the ships through its Madeira-based subsidiary. So SunStone does not hold ships on its balance sheet. What SunStone does is manage the financing, design, technical management, and commercial chartering of the ships. So SunStone’s assets are mainly contracts (charters, leases) and design rights.

So what this means is that China Merchants Heavy Industry (CMHI) builds the ship, and CMHI is part of China Merchants Industry Holdings, a division of China Merchants Group (CMG), one of China’s largest state-owned conglomerates. The money is provided by a leasing company such as China Merchants Bank Leasing, ICBC Leasing, Minsheng Leasing, or another big Chinese financial lessor. These companies provide 100% financing for the vessel’s construction, usually through a special-purpose company that becomes the legal owner of the ship. SunStone doesn’t buy the ship, instead, it takes a bareboat charter or finance lease. This gives SunStone full control over the ship’s operations but not legal ownership. However SunStone must handle the ship’s outfitting, class certification, technical systems, and crewing (via its subsidiaries, especially in Madeira).

It also looks as if SunStone designs the ship layout to ensures the vessel meets the standards of its target cruise clients. SunStone then sub-charters ships to cruise operators, who then take the ship and run guest-facing cruises. They market the ship, sell the voyages, and handle onboard hospitality.

What SunStone is operating is a asset-light model, made possible by state-backed Chinese industry and finance.

There is no ownership connection between Quark Expeditions and SunStone. The relationship is purely charter-based, with Quark chartering Ocean Explorer for specific seasons (e.g. Antarctica and Arctic) under a contractual agreement. SunStone also charters out sister ships (like Greg Mortimer, Ocean Victory) to Aurora Expeditions, Vantage Travel, and Albatros Expeditions.

In the case of Le Lyrial, Ponant is the owner, but they do charter out the ship to third parties (some can be co-branded), who also can bring their own explorer team onboard.

Why should SunStone register their ships in Madeira?

In reality there a numerous good reasons for doing so. A Madeira flag (more properly, a Portuguese flag via the Madeira International Shipping Register, or MAR) offers several important advantages for a vessel like the Ocean Explorer, especially in the context of expedition cruising and polar operations.

Firstly, it has access to the EU Legal and Regulatory Framework, and means that they are fully compliant with EU maritime law. This gives shipowners access to EU cabotage rights (under certain conditions), a harmonised safety and labour regulations under IMO and EU oversight, and legal credibility with passengers, insurers, and port authorities. This last point is a key difference from so-called “flags of convenience” like Liberia or Panama, which are sometimes viewed skeptically in regulatory or passenger contexts.

Secondly, Madeira has a competitive tax regime, since the register is part of the Madeira Free Trade Zone. And this means reduced corporate income tax rates for shipping companies (5% under certain conditions), no capital gains tax on ship sales, no withholding tax on dividends, interest or royalties, an exemption from VAT on vessel acquisition and operation, and no tax on crew wages.

Thirdly, Madeira has flexible labour and crewing rules, unlike in mainland Portugal or more generally in the EU. This means hiring crew from non-EU countries under more flexible terms, no social security contributions to Portugal required for non-Portuguese crew, and no restrictions on crew nationality or numbers, as long as STCW standards are met. This is crucial for international expedition cruise ships, which often carry mixed-nationality crews and operate globally.

Fourth, Portugal and Madeira have a strong maritime reputation. For example, they are on the Paris MoU White List, which mean MAR-flagged vessels are rarely detained during port state control inspections in Europe. They are part of the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) network, which wins them enhanced insurance terms, reduced risk of delays, and finally reassures passengers.

Lastly, ships like Ocean Explorer, built for polar expeditions, benefit from MAR’s recognition of Polar Code compliance through classification societies like DNV, Lloyd’s Register, or Bureau Veritas, easy integration with EU passenger safety rules (Directive 2009/45/EC) and SOLAS/Polar Code provisions, and no barriers to chartering or reflagging for seasonal operations.

In other words, registration with MAR allows Ocean Explorer to be globally operational without legal complications, especially important when changing regions or contractual partners. Remembering that charterers prefer neutrality and want legal clarity for international charter agreements. They want to see high inspection and documentation standards that are familiar to major cruise terminals, insurers, and classification societies. And this makes MAR-flagged vessels easier to market, charter, insure, and operate worldwide.

The X-Bow®, developed by the Norwegian company Ulstein Group, is a ship hull design that represents a radical departure from conventional bow shapes. Introduced in 2005 and first launched on a vessel in 2006, the X-Bow® was conceived not simply as a visual or branding innovation, but as a functional redesign aimed at significantly improving performance in rough seas, e.g. especially for polar vessels.

At its core, the X-Bow® (short for “Extreme Bow”) is a forward-sloping, inverted bow. Instead of the traditional flared shape that rises upward and widens toward the deck, the X-Bow® slopes down and forward, with a streamlined profile that cuts through waves rather than riding over them. It eliminates the sharp break between bow and hull, resulting in a more continuous hull surface. The innovation lies in the hydrodynamic performance, i.e. the shape reduces pitching, slamming, and vertical accelerations which are key factors in comfort, fuel efficiency, and safety in rough waters.

These two videos (sorry about all the ad’s) are a little technical but they both discuss evolutions in hull design, and explain the pro’s and con’s of the X-Bow®, compared to other hull designs.

The X-Bow® has proven to be one of the most significant hull design innovations in 21st-century shipbuilding. What began as a radical sketch in the Ulstein design lab is now a proven standard across multiple vessel classes.

Future iterations may look to embedding the X-Bow® within a broader, system-wide rethink of how ships interact with their environment. This can range from zero-emission propulsion, integrate battery-electric propulsion, waste heat recovery to adaptive hull geometries and intelligent navigation in ice. There is also the suggestion to apply the same inverted, wave-piercing principle to the stern of the vessel. This could be especially valuable for dynamic positioning and operating in reverse. In that sense, the X-Bow® is less a singular solution than a first major step toward a new era of maritime design.

That’s what the publicity material wants us to believe. but I just felt that it was a “cool” looking ship, and it certain cut through ice when we went north.

SunStone has announced the new Boundless-Class

In 2023 SunStone announced the new Boundless-Class (above) and mentioned four firm orders and six options. It is a larger vessels (~125 metres long, ~21 metres beam), ~13,000 GT, ~20–30 % more passenger capacity (possibly 200-260 with a crew of 140), but building out from the core expedition technology already available in the Infinity-Class (e.g. Ocean Explorer). Announcements include all cabins with private balconies, and a mid‑deck pool under a retractable glass dome, designed for both warm- and cold-weather cruising. Suggestions point to a more luxury focus with interiors crafted by top European designers, a garage for up to 20 zodiacs, and luxury amenities tailored to charterers and research users (including labs).

These new ships will shares Infinity’s propulsion baseline, i.e. diesel-electric, zero-speed stabilisers and dynamic positioning. In addition they retain the X-Bow®, the Polar Class 6 (PC6), but adopt an electric grid architecture designed to accommodate future low-carbon technologies such as fuel cells, batteries, and solar arrays. One generator space is reserved for modular insertion. Shore-power connection will be standard at port.

The new design also retains many recent developments in the existing Infinity-Class, namely controllable pitch propellers, a bow thruster (~880 kW), Tier III engines, selective catalytic reduction (SCR), and use of marine gas oil (MGO). Other existing enhancements include waste heat recovery, LED lighting, and wastewater treatment. Virtual anchoring (station keeping via DP) is mentioned which will reduce physical anchoring and lower environmental impact in sensitive areas. Also mentioned is Safe Return to Port (SRtP) classification compliance which ensures significant onboard redundancy and resilience in case of emergencies.

What is less clear is delivery dates, etc. Information is confusing and even contradictory. Most sources (as of July 2025) say SunStone has not yet finalised a shipyard contract. Only a “design commitment” with OSK-ShipTech and in-principle planning for a Q2 2025 letter of intent with a yet-unnamed yard. Despite SunStone’s long-term relationships with clients like Aurora Expeditions, Quark Expeditions, and Albatros Expeditions for their earlier Infinity-class ships, none have been publicly attributed or assigned to the upcoming Boundless vessels so far.

As of 2025, the construction strategy includes partnering with either European or Asian yards capable of delivering multiple ships per year. It’s mentioned that the firm order for the first builds is expected in late 2025, and delivery of the first ships projected for Q3 2026 (which is totally unrealistic or even misleading). For example, the earlier Infinity-Class took 22–26 months from steel-cutting to delivery.

It’s all the more surprising since in January 2023, SunStone’s CEO stated that the new Boundless-Class would not be built in China, unlike the earlier Infinity-Class that was constructed at China Merchants Heavy Industry. In mid‑2025 SunStone confirmed that none of the possible shipyards are China‑based, and in July 2025, they confirmed that no Chinese shipyard has been selected or even mentioned in connection with the Boundless-Class. This most recent statement from SunStone indicate a deliberate move away from China-based builders.

SunStone also said they are moving toward a one-yard build model in Europe, rather than splitting hull and fit-out between Asia and Europe as with Infinity-Class. One strong option could be Ulstein Verft who designed both classes and completed the outfitting of the Infinity-Class. An alternative could be Fincantieri (the builder of the Boreal-Class for Ponant) which also has yards in Norway. and we should not forget that The Boundless-Class is being developed by OSK-ShipTech (Denmark) and Steen Friis Design, both European naval architecture firms.

As of Q2–Q3 2025, Ulstein Verft is actively outfitting several high-complexity vessels, including the Nexans Electra cable‑laying vessel. But according to Ulstein Group’s 2024 report, they currently have ongoing construction of an expedition cruise vessel for SunStone (one of the Infinity-Class) plus multiple Construction Service Operation Vessels CSOV). It was also mentioned that SunStone might consider contracting more than one yard, to accelerate the introduction of the Boundless-Class.

So it’s “watch this space”.

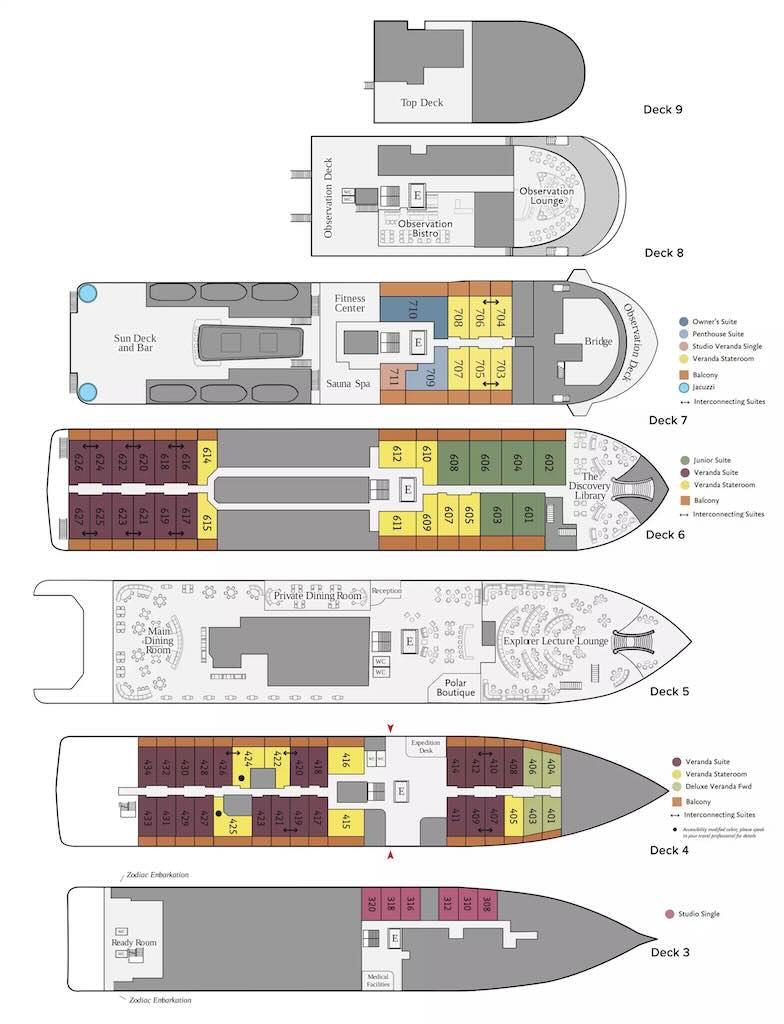

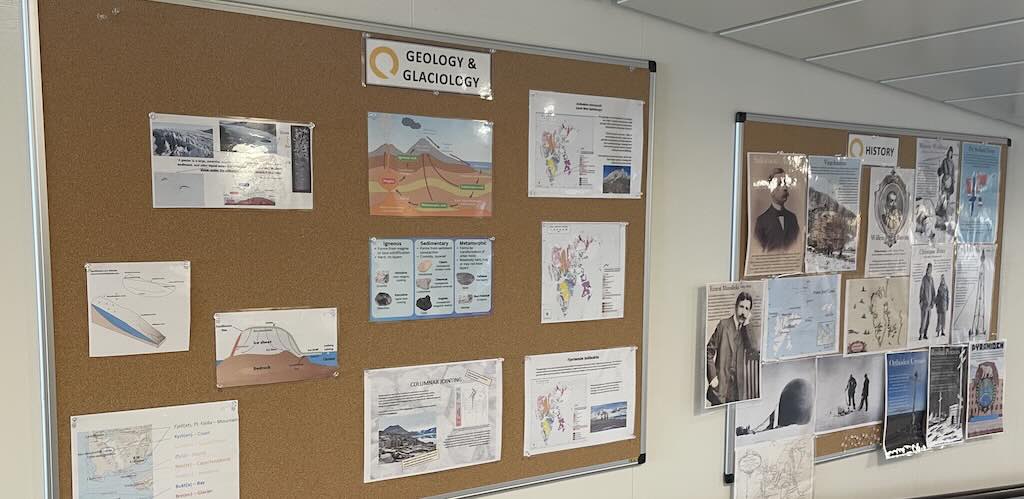

Deck plans

Above – Quark Ocean Explorer (there is now a small pool on the Sun Deck)

Below – Ponant Le Lyrial

Basic description

Ocean Explorer is 104.4 metres in overall length with a beam of 18.4 metres. It has a compact but solid presence, prioritising sea stability and structural strength over length. Its broad beam relative to its length enhances both internal volume and sea stability, particularly in polar regions.

By contrast, Le Lyrial is significantly longer at 142 metres, yet maintains a slightly narrower beam of 18 metres. This gives it a more elongated, yacht-like silhouette ideal for scenic cruising and elegant docking, but less optimised for turbulent or ice-bound waters.

Ocean Explorer carries around 8,000 gross registered tons (GRT), whereas Le Lyrial, has 10,944 GRT. In Le Lyrial this addition space serves more passengers and adds some additional luxury amenities, lounges, and spa areas.

With a draft of about 5.3 metres and a Polar Class 6 (PC6) hull, Ocean Explorer is certified for extended navigation in medium first-year ice, making it highly suitable for deep Arctic or Antarctic itineraries. In practice this means it’s certified for summer/autumn operation in medium first-year ice which may include old ice inclusions, equivalent to an ice thickness of 70 to 120 cm.

Ocean Explorers overall performance is characterised by a top speed of ~16.5 knots in open water, with a fuel consumption of ~26.4 MT/day. Its economic service speed is ~11 knots with a fuel consumption of ~11.9 MT/day.

Onboard machinery is listed as:-

- Diesel generators: 4 × Wartsila (2 × W8L20, 2 × W6L20), ~1,080 kW each, total ~4,321 kW

- Propellers: 2 × controllable-pitch (CP), ~201.5 rpm

- Thrusters: 1 × bow thruster (~880 kW)

- Stabilisers: Rolls‑Royce Aquarius 100 (at-rest stabilisation)

- Dynamic positioning: Kongsberg K‑POS system.

People don’t think much about what makes up the 8,000 GRT of Ocean Explorer, but a substantial part of that weight is stored in tanks:-

- Marine gas oil capacity: ~589 cubic-metres

- Lube oil: ~31.5 cubic-metres

- Fresh water: ~183 cubic-metres

- Ballast water: ~1,207 cubic-metres

- Fresh water production: ~80 cubic-metres/day (reverse osmosis) + ~15 cublic-metres/day (evaporation).

By comparison Le Lyrial, has a shallower draft of 4.7 metres and is rated Ice Class 1C, allowing for light ice navigation only, enough for seasonal Antarctic voyages, but not designed for prolonged or more demanding ice conditions.

Here we hit already a not-so subtile difference in meaning between “polar class” and “ice class”. Polar Class is defined by the IACS Unified Requirements for Polar Class Ships (International Association of Classification Societies). Ice Class is defined by the Finnish-Swedish Ice Class Rules, primarily for operations in the Baltic Sea. These systems overlap in function but are not equivalent. They serve different environments and regulatory frameworks. But the overall message is that a ship rated PC6 far exceeds the capabilities of a 1C-class vessel and can operate under significantly harsher conditions.

Ocean Explorer features the innovative Ulstein X-Bow®, which slices through waves rather than riding over them, reducing both pitching and passenger fatigue in rough seas. This is a hallmark of serious expedition design.

Le Lyrial uses a more conventional forward-bow and fin stabilisers, offering solid comfort in moderate waters but without the advanced hydrodynamic benefits of the X-Bow®.

Both vessels operate on diesel-electric systems, but Ocean Explorer uses dual Rolls-Royce Azimuth thrusters and dynamic positioning systems, enabling precise station-keeping without anchors.

Le Lyrial employs Azipod propulsion, optimised for manoeuvrability and quiet operation, but lacks the same level of dynamic stationing and energy optimisation found in newer expedition builds like Ocean Explorer.

Passenger perspective

We have already established that Ocean Explorer is a smaller ship compared to Le Lyrial, i.e. 104.4 metres vs 142 metres, and 8,228 GT vs 10,944 GT.

Ocean Explorer has a maximum capacity of 138 passengers in 70 cabins, with a crew of 105 and an expedition team of 22 (safety certification and lifeboat capacity 300 maximum). Whereas Le Lyrial has a maximum capacity of 264 passengers (typically ~200 in polar itineraries) in 122 cabins, ~140 crew and ~18 expedition team (safety certification and lifeboat capacity 400 maximum). So Ocean Explorer has a higher potential crew-to-passenger ratio (0.92) compared to 0.60–0.80 for Le Lyrial. Also Ocean Explorer has a higher per-passenger space measured in GT/pax, with ~59.6 GT per passenger, compared to ~41.5 GT per passenger for Le Lyrial. It must be said that the way space is used on both ships is quite different, and a brut comparison does not tell the whole story.

In terms of explorer equipment both use Milpro MK5 HD zodiacs, mostly with a single 60 horsepower 4-stroke outboard motor (usually Yamaha). Ocean Explorer has 15 zodiacs stored on Deck 4, with 2 cranes, although I only saw one operating. Le Lyrial has 11 zodiacs stored on the top, Deck 7, and I only saw one crane being used.

As far as I could see Ocean Explorer offers a more diverse and large-scale kayak and SUP (stand‑up paddle-boards) program, with a total of 12 tandem kayaks, 16 inflatable kayaks, and 6 inflatable SUPs. As far as I know, but I may be wrong, Le Lyrial only offers around 10 rigid, single-seater sea kayaks, possibly Prijon Excursion EVO.

The zodiac embarkation/disembarkation routines were quite different. Ocean Explorer was able to take all 98 passengers ashore or cruising at the same time, although disembarkation was sequenced in four groups. The biggest difference was conditioned by the existence of a mudroom (ready room seen below) and two dedicated sea-level exit points both on Deck 3.

It all started with an early online query asking for sizes for the Quark bright-yellow polar parka, and muck boots. The parka (which we could keep) was in my cabin, and I had to immediate try it on, and change it if needed. On both ships the parka’s were waterproof and windproof, but the Quark parka also came with a detachable insulating liner that could be removed and warn separately.

Everyone had to go down to the mudroom, with the parka and thick socks, and each cabin had an open metal locker, with a life vest and (right sized) muck boots. We all had to try on the boots, and make sure the life vest was properly adjusted. The existence of the mudroom meant we left the life vest and boots down by the sea level exit point. Some people also left the parka in their locker.

The two sea level exit points are basically just holes in the side of the hull (in principle they could disembark/embark two zodiacs almost simultaneously, but they didn’t need to). We were all “scanned” off and on, and we disembarked in groups of eight per zodiac. Returned from a landing, we all had to wash our boots, before changing in the locker room.

On La Lyrial we were all allocated to different groups (based upon Deck and language), and given that there were more passengers and less zodiacs, disembarkation/return overlapped and sequencing was spread over a longer period of time. The red Ponant parka did not come with a warm lining, but we could also keep it. The selection of boots and the adjustment of the life vest was done onboard, and since there was no mudroom, they were keep outside each cabin. We then had to go to the stern lounge on Deck 3 to put on our boots and life vest, then be scanned off the stern observation deck and go down to the Marina Deck (Deck 2) to find the zodiacs. Returning we washed our boots on Deck 2, were scanned onboard and remove the life vest and muck boots on the Deck 3 before returning to our cabins.

Broadly speaking on each ship passengers were ashore or cruising in the zodiac twice per day for a total of between 3-4 hours, but on Le Lyrial this was spread over a longer period in the day. Each ship planned to visit two different places per day, so there was no real different between the two explorer schedules.

Public spaces

Aside from the cabins, dining areas, and excursion areas (zodiacs, mudrooms, loading bays, etc.), each ship has a variety of public spaces, e.g. observation lounges, lecture theatres/rooms, library/reading rooms, bars/lounges, wellness areas/spas, fitness rooms, and a variety of reception areas in atriums or lobbies.

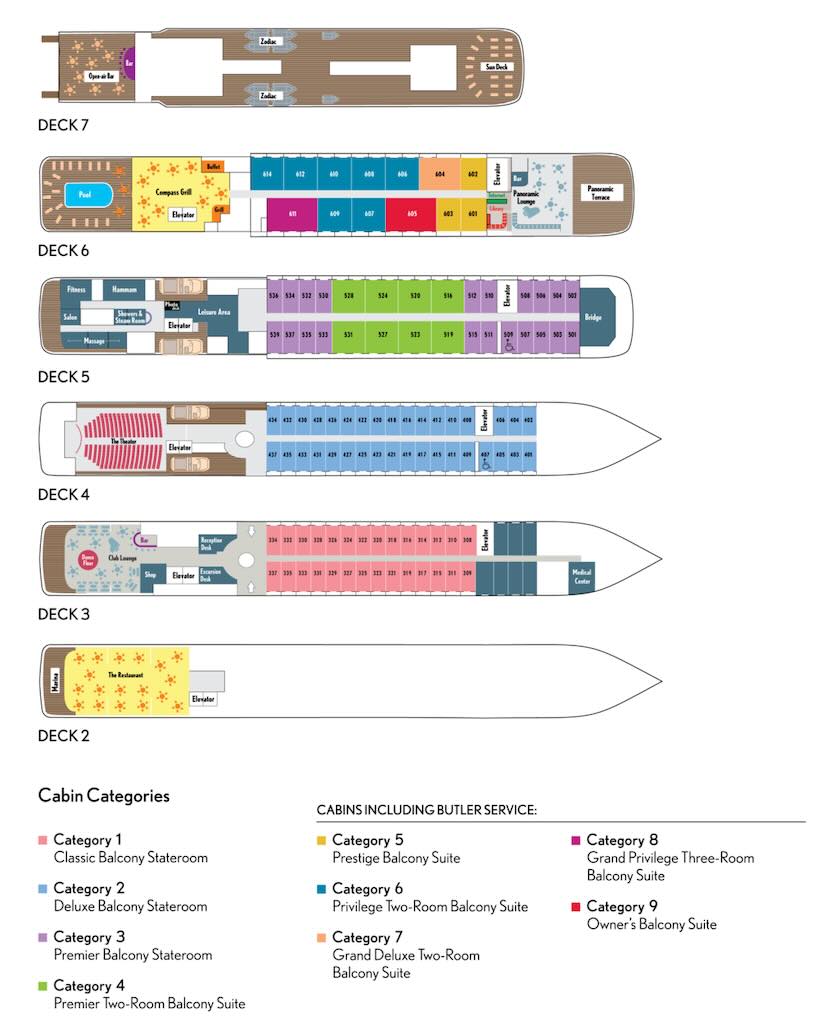

The central public space on the Quark Ocean Explorer is situated on Deck 4/Deck 5 with a partial 2-deck atrium, that is home to reception desk, expedition desk and boutique.

It’s also the access to the Main Dining Room (seating for all passengers), and the smallish forward Latitude Bar (comfortable, but with limited views as seen below), which then accessed the Explorer Lecture Lounge (used for briefings, etc. and which I felt might be a bit small if the ship were full).

In fact part of the seating was placed behind the TV screens, etc., but it’s here that there was the wide and elegant staircase leading up to the Discovery Library on Deck 6. There was also a piano, which remained silent throughout the voyage.

It is this second forward 2-floor atrium that has the glass windows set into the ships bow. First impressions of this forward-atrium were very positive, but the space on Deck 5 appeared little used. However, the library on Deck 6 was very comfortable, in part due to a 24/24 “real” ground-coffee machine, a permanent supply of biscuits, and a very extensive supply of books (the collection of books on Le Lyrial was ridiculous by comparison). However, on Le Lyrial passengers actively used the games and tables, whereas I never saw anyone playing the games on offer in Quark’s Ocean Explorer library. Passengers on Quark’s Ocean Explorer were very sedate, by comparison with those on Le Lyrial.

On Deck 8 of Quark’s Ocean Explorer there was the bistro and a very pleasant Observation Lounge, with the second 24/24 “real” ground-coffee machine (early breakfast was served here from 07:00). In front of the Observation Lounge was wide panoramic outdoor Observation Deck. There was a good collection of binoculars available, as well as tripods and several high-powered, portable telescope with tripods, optimised for terrestrial viewing. it was on this deck that the explorer team would start the day scanning the landing areas for wildlife.

On the aft of Deck 7 there was a small heated outdoor pool, two jacuzzis, and sun loungers. There was also a narrow observation deck in front of the bridge (accessed from Deck 8). On Deck 7 passengers could also find a decent little gym, and a spa area with a small sauna, but with a window opened to the sea.

On Deck 3 of Le Lyrial there was a “grand atrium” with a refined lobby linking reception, boutique, concierge, excursions bookings, photo/media desk, etc. and lounge entrance. The main lounge could seats ~110 inside plus ~30 on an outdoor terrace. I spent most of my time in the smaller Panoramic Lounge, with its terrace and pool.

Le Lyrial has an AV-equipped, ~250 seat theatre, used for educational lectures and evening performances. One very substantial difference, was that Le Lyrial offers a very extensive entertainment package during the daytime, but above all every evening. On Quark’s Ocean Explorer only one evening was dedicated to a musical quiz, which was well received.

The Ocean Explorer team

Firstly, I’m not trying to critique the exploration team on Le Lyrial, they were very good, but the team on Ocean Explorer were exceptional (IMHO). Secondly, it may be difficult to compare visiting the Antarctic and the Arctic. Thirdly, the two ships are different, and the number of passengers differed. Finally, Le Lyrial certainly also prioritised entertainment every evening, and the exploration team had to be far more multi-talented. In the Quark team we didn’t see anyone singing, dancing, playing musical instruments, or “making a fool of themselves”, except one who appeared to a “real character”, in a very positive way. The exploration team on Le Lyrial also had to work in French, English and Mandarin.

The Quark expedition team had a larger core of naturalists and guides, along with a good team of zodiac drivers. As an example, the zodiac drivers were (slightly) more attentive about safety onboard, and also appeared slightly more informed about what we were seeing. Again, no criticism intended to the exploration team on Le Lyrial.

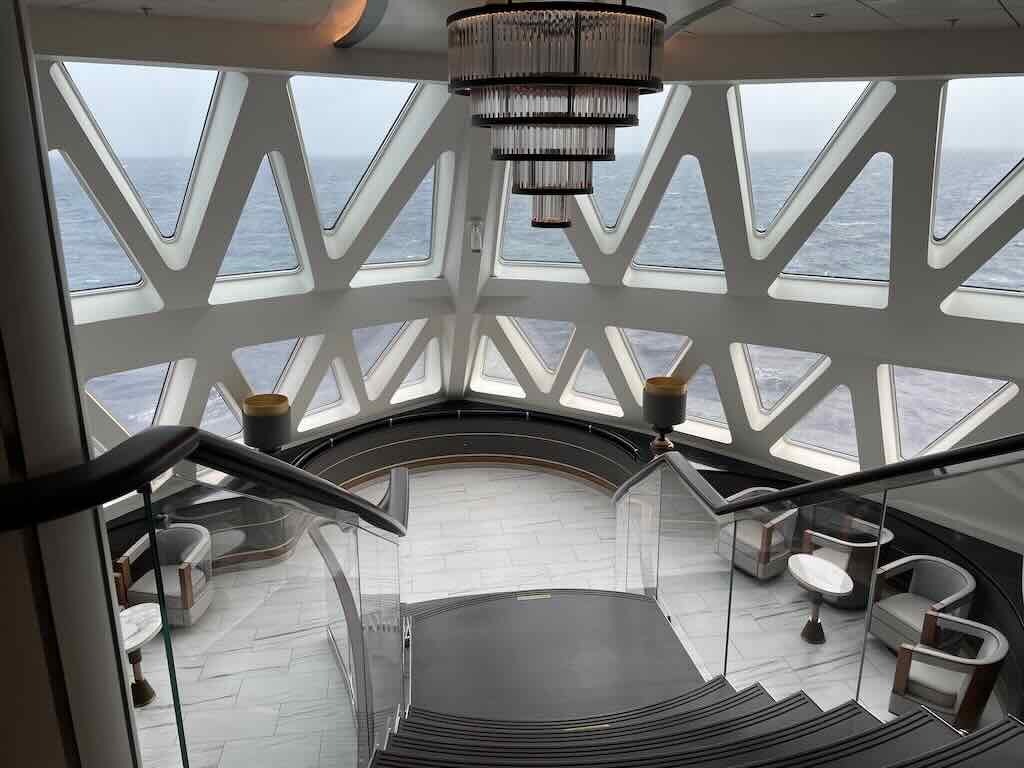

There was a clear, more “naturalist” focus on the Ocean Explorer. For example:-

- The team appeared to have a slightly stronger academic background, and/but it was very Anglophone centric, with just a sprinkling of Chinese Mandarin

- The exploration team leader had a stronger, very professional, very visible presence as head of the team

- The presentations and briefings were more professional, better prepared, longer, and more focused

- The exploration team members were more accessible, almost every day I ate in the bistro with one of more of the team

- Given the polar bear risk, groups were more compact and constantly in contact with a member of the exploration team (who were always armed)

- A stronger focus on offering different graded walks (e.g. long, intermediate, and contemplative)

- A more complete kayak and paddle offering

- More laidback atmosphere, e.g. no captain’s dinner, no photo-op with the captain, etc.

- The team photographer collected a massive archive of photos and authored a cruise video which were sent to all participants (on Le Lyrial you could buy a CD)

- The focus onboard was centred wholly on exploration, e.g. with a selection binoculars, etc. in the Deck 8 lounge, an extensive library of books on Deck 6, and info panels around the ship, some refreshed almost daily.

- Finally, on all the free walls there were big photos of explorer related topics.

The cabins

Above we have my cabin on Ocean Explorer, and below my cabin on Le Lyrial. I preferred the general decor on the Le Lyrial, but I found the storage in the room, etc. a bit better on Ocean Explorer (although I’m not a fan of fake wood). This could be a deciding factor for a couple (apart from the price and itinerary). The bathroom on Ocean Explorer, without the separate WC, was slightly more spacious. It’s worth pointing out in rough seas it best not to have too much space, and to have lots of rails and handles. Otherwise both cabins were both comfortable.

The one thing that really annoyed me, on both ships, was the fact that vacuum cleaners, service trolleys, and used laundry bags were always left in the corridors. Either the ships were poorly designed, or the staff were not properly managed (or listened to).

MAGS waste gasification

Given that Ocean Explorer documentation and sales literature continuously repeats that it has MAGS waste gasification, we better find out what it is. It’s short for Micro Auto Gasification System (MAGS), a compact, high-temperature unit that converts solid waste, such as food scraps, plastics, and paper, into clean gas and a small amount of inert ash through a process called auto-gasification. It requires no external fuel or water once started, and it operates efficiently and cleanly within strict international environmental standards.

On modern explorer ships, especially those operating in remote or ecologically sensitive regions, MAGS is essential. It dramatically reduces the volume of waste by up to 95%, eliminates the need for waste offloading in ports, and supports extended autonomous operations. The heat generated can be reused onboard, improving energy efficiency. By ensuring safe, hygienic, and regulation-compliant waste management, MAGS enables long-range expeditions to maintain both operational independence and environmental responsibility.

Rescue and lifeboats

On the day we boarded, we had a safety briefing. This included donning the life-vest found in each cabin, the location of the two muster stations in the Explorer Lecture Lounge on Deck 5, and the route to the two life boats on Deck 7 next to the pool and Jacuzzis. Each passenger was allocated to one of two muster stations, 1 or 2, which I think represented port and starboard cabins.

On Deck 7 we saw the two Totally Enclosed Lifeboat (TELB) probably made by Ningbo New Marine Lifesaving Equipment Co., Ltd., which clearly brands its products as “NPT”.

The remarkable thing is that all ships must have life boats, and they all appear to be slightly different, but always orange. Bright orange stands out against dark blue or grey ocean water, white sea ice or surf, and in overcast skies. What we see above is that this life boat is 9.6 m long, 3.95 m wide, the hull is 1.25 deep, and with the canopy the total height is 3.8 m.

SOLAS stands for the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, established in 1914 and maintained by the International Maritime Organization. It is the primary international treaty governing safety standards for merchant and passenger ships, including lifeboats and life rafts, fire protection, navigation systems, and emergency drills and equipment.

For a small expedition vessel with 300 people on board (passengers + crew), SOLAS requires lifeboat capacity for 100% of everyone, plus additional life raft capacity for at least 25%. This should be in the form of two life boats, each with a capacity of 150 people. Also somewhere on the ship there should/would be inflatable life rafts for at least 75 more people, usually mounted on deck in canisters. There is also a requirement for one fast rescue boat (FRB), used for man-overboard recovery, emergencies, or backup rescue. Ocean Explorer has two of these FRBs.

The life boat should be fully enclosed, fire-protected, self-righting, and include a internal diesel engine, with a fixed fuel supply, and manual steering via rudder and tiller. It should be fitted with essential survival gear (water, rations, first aid, thermal blankets, compass, etc.), radio beacons (EPIRBs) and signalling equipment, and be equipped with external and internal battery-powered lighting.

These life boats are (or should be) designed to remain afloat and protect occupants for at least 30 days in survival conditions. The total volume of the life boat is 134 cubic metres, and an enclosed lifeboat must carry enough fuel to allow it to travel at 6 knots for 24 hours (so 100-150 litres).

Despite being in a cold ocean SOLAS‑compliant lifeboats are not require to have onboard heaters or a water maker. Lifeboats typically rely on survival blankets and packaged fresh water in containers (enough for at least 3 litres/person/day). The trick is in the detail since the 3 litres/person/day actually means only 3 liters per person total (not per day), for initial survival, not 30 days. Instead of 13,500 litres of fresh water (13.5 cubic metres) the life boat only needs to carry 450 litres water rations for 150 people.

So overall there is room for people to sit packed but not tightly compressed, with just enough space for supplies, minimal movement, and emergency gear, consistent with survival-mode conditions, not comfort. And not forgetting that a life boat contains only enough air to last a few hours sealed, but requires ventilation beyond that.

The fact is that the longer it takes to locate a lifeboat, the lower the statistical chance of timely rescue. This is documented in polar SAR (search & rescue) modelling. The target is to ensure survival for 5 days minimum, but beyond that, it is not guaranteed. Beyond 96 hours, the risk of remaining lost or not surviving increases substantially, not because the boat itself will fail, but because the rescue window narrows, human resilience declines rapidly, and the environment punishes even the best equipment over time. That’s exactly why the IMO Polar Code mandates lifeboat provisions for 5 days, and why most rescue plans target a ≤72-hour window.

The amazing thing is that despite life boats being mandatory, they all look slightly different. In fact the basic hull is more or less the same and is made from glass-reinforced polyester (GRP) or fire-retardant resin-infused composites. But the canopy is often custom built, and accessories (e.g. layout, hatches, rigging, access points, lifting sockets, etc.) are often different. Lift boats are registered and certified individually, per flag state.

Finally, life boats must be inspected for hull integrity, engine start and run, steering and release gear, fuel and freshwater supplies, ventilation and watertight integrity, survival equipment (flares, rations, EPIRB, compass, etc.), and the release units. The crew are obliged to make (and log) a weekly visual check of lifeboats, engines, hatches, and lashings. Properly trained crew must operate the engine and steering gear, and check release mechanisms monthly. A certified technician must make a detailed inspection of release gear, davits, structure, and equipment annually. And a service company approved by the flag state must do a load test and release under full weight every five years.

The ship also had two fast rescue boat (FRB), used for man-overboard recovery, emergencies, or backup rescue (as seen above). There is a slewing-type single-arm davit, typical for rapid-launch FRBs rather than the heavier twin-davit setups used for lifeboats. It looks to have a rigid hull with foam or inflatable collar (RHIB).

Communications and navigation antennas

Probably because the Quark Ocean Explorer’s top deck (Deck 9) was smaller than the top deck of the Le Lyrial, there appeared to be a Christmas tree of antennas.

My photo (above) doesn’t capture all of them, and unfortunately passenger were not allowed on the top deck (shame). So I’m doing a bit of guessing:-

- There were three large Radomes housing stabilised satellite antennas, usually for Internet access (VSAT – Very Small Aperture Terminal), telephony and satellite TV reception.

- I think just behind the green tarpaulin there is what looks like a Starlink Maritime (many polar and expedition ships carry one or two to offload passenger internet)

- Not visible in the above photo there was a Wärtsilä marine navigation radar scanner (X-band or S-band radar)

- Not visible in the photo there was a Thales Dome Antenna, either a GNSS (GPS+GLONASS+Galileo) receiver or backup Satcom. In any case the ship needs an antenna for its ECDIS (Electronic Chart Display and Information System), Dynamic Positioning (DP), and AIS data correlation.

- The taller vertical whip antennas provide VHF/UHF communications, e.g. marine VHF (Channel 16 distress, bridge-to-bridge), AIS transceiver, and possibly UHF for expedition crew radios.

- The shorter, stubbier antennas are usually GPS/GNSS/AIS positioning receivers.

- There was also (not shown in photo) a covered unit that could have been a CCTV camera array, or even a laser rangefinder.