Le Lyrial is a cruise ship operated by the Compagnie du Ponant that made its inaugural cruise in May 2015 (check out the video Ponant Le Lyrial Expedition Cruise Ship Tour).

My cruise on this ship was entitled “Expedition to the Southern Lands“, and took place November-December 2024.

In Le Lyrial – a luxury expedition cruise ship I try to describe my life onboard, whereas here I try to delve a little deeper into what is hidden behind those watertight doors marked ‘No Entry’ or ‘Crew Only’.

I will also try to look at the evolution of cruise ships in general.

And I have also prepared three addition posts covering the day-by-day life onboard, i.e. the activities, conferences, excursions, etc.

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 1-7)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 8-11)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 12-17)

I have tried to address the following question:-

- What type of cruise ship is Le Lyrial?

- Le Lyrial – is it a tradable asset?

- How about some useful jargon?

- Le Lyrial – what does it all mean?

- What does ‘Ice Class – 1C mean’?

- What does ‘Classification – Bureau Veritas’ mean?

- What does ‘Flag – France’ mean?

- Why is Le Lyrial registered in Wallis and Futuna?

- How can Le Lyrial safely navigate Artic and Antarctic waters?

- What is ice radar?

- Do you know the history of cruise ships?

- What is the world market for cruises?

- What about the pricing of cruises?

- What’s life like on board for a cleaner?

- What’s life like on board for a junior officer?

A great way to open the subject of cruise ships is to check out Cruise Ship Design Construction Building and Cruise Ship Engine Power, Propulsion, Fuel.

What type of cruise ship is Le Lyrial?

In my description of life onboard the Le Lyrial, I mentioned the different between ship and boat, and what is the definition of a cruise ship. And the reality is that the definitions a quite imprecise.

But what is sure is that Le Lyrial is a small cruise ship, and more precisely an expedition ship able to navigate in restricted areas such as polar regions, small islands, or shallow waterways.

This means it has an ice-class hull (i.e. reinforced), and can operate in the Arctic Ocean and the Antarctic ice sheet. This also usual implies that it is equipped with dynamic positioning systems and/or advanced thrusters for safe navigation in uncharted waters. And it also means that Le Lyrial is Polar Code Compliant, with a hull thickness of 20-50 mm in ice belt areas. In addition, the hull should be made from high-strength, low-alloy steel, and the shape of the hull will be slightly more sloping or curved with a bow that helps push ice aside as the ship moves forward. Internal structures, such as frames and bulkheads, are also usually strengthened to distribute ice pressure across the hull.

Le Lyrial - is it a tradable asset?

On Saturday 11th April, 2015, Fincantieri delivered Le Lyrial to the French shipowner Compagnie du Ponant, at the time part of the Bridgepoint Group.

Wikipedia mentions that Le Lyrial was the fourth ship of a “class” defined by the Le Boreal, first put into service in May 2010. A year later, the company began operating the second ship of the class, L’Austral, and in June 2013 the third ship of the class was added to the fleet, Le Soléal.

These are simple statements, but what does it all mean? Let’s go back in time…to 1988.

In 1988, Compagnie du Ponant was established by a group of French Merchant Navy officers, including Jean-Emmanuel Sauvée, Philippe Videau and Bruno Delisle. Their idea was to introduce a new style of cruising under the French flag, combining luxury with unique sea travel itineraries.

I’m not sure why, but many of the references have dropped the second ‘e’ on the name of Jean-Emmanuel Sauvée.

The grandfather of Jean-Emmanuel Sauvée, a certain Jean Sauvée, was a maritime journalist, co-founder of the Le Marin newspaper in 1946. I think at the time Jean Sauvée was editor of ‘Ouest-France‘ in Paris. His son, also Jean, a captain, was later appointed Administrateur Général des Affaires Maritimes, the office in charge of maritime matters for the French government.

Jean-Emmanuel Sauvée is a graduate of the École Nationale Supérieure Maritime and the Université de Bretagne-Occidentale. His career started when he was just 16, as an officer-cadet with Brittany Ferries. He then worked for Bourbon Offshore and then Compagnie Générale Maritime. In 1988, he joined forces with Philippe Videau and a team of fellow officers to create La Compagnie des Iles du Ponant.

Today there exits the Fondation Maritime Jean Sauvée, which aims to promote maritime intangible heritage.

It would appear that Philippe Videau has ‘moved on’ (2024) and a new ship ‘Exploris One’ was relaunched in December 2023. Originally ‘Silver Explorer’, renovated in 2018, the new ship hosts around 100 passengers and appears to target exclusively the Francophone explorer market (see recent video).

Ponant’s first vessel, Le Ponant, a three-masted sailing yacht, was launched in 1991 and remains in service today. Originally built by the French shipyard Société Française de Construction Navales (SFCN) it underwent a refurbishment in 2022. However, it still offers an authentic sailing experiences with its 1,000 square meters of sails. It is also the first sailing yacht to be awarded the prestigious Relais & Châteaux label in 2023.

The Société Française de Construction Navale (SFCN) was a prominent shipyard located in Villeneuve-la-Garenne, France (see Chantiers Navals). Established as the successor to the Chantiers Navals Franco-Belges in 1918, the SFCN specialized in the construction and repair of various vessels, including warships and commercial ships. In the late 1980s, the shipyard expanded its expertise to include luxury sailing yachts. Despite its achievements, the SFCN ceased operations in Villeneuve-la-Garenne in 1992, with its activities relocating to Lorient (more like disappeared than relocated).

By the late 2000s, Ponant saw growing competition in the luxury expedition cruise segment from firms like Silversea and Lindblad Expeditions. To expand internationally and order newer, more modern ships, Ponant needed a strong financial backer. In 2004, CMA CGM, France’s largest container shipping company, acquired a 70% stake in Compagnie des Îles du Ponant. At the time of acquisition, Ponant operated two vessels, Le Ponant and the motor yacht Le Levant (now Clio), introduced in 1998. This strategic investment marked CMA CGM’s entry into the luxury cruise market, aiming to diversify its maritime offerings beyond container shipping.

Following the acquisition, Ponant expanded its fleet by purchasing Le Diamant (now Ocean Diamond) in 2004, a luxury liner built in 1974. The company continued its growth with the introduction of a series of four identical luxury sister ships, namely Le Boréal in 2010, L’Austral in 2011, Le Soléal in 2013, and Le Lyrial in 2015.

In 2006, as part of its integration into the CMA CGM Group, Ponant relocated its headquarters from Nantes to Marseille, aligning its operations more closely with its parent company’s central hub. By 2012, CMA CGM decided to refocus on its core container shipping business and sold Compagnie du Ponant to Bridgepoint Capital. At the time of the sale, Ponant operated three ships, employed 580 individuals (including 500 seamen), and had already ordered the Le Boréal family of vessels.

Throughout its ownership by CMA CGM, Compagnie du Ponant evolved from a niche cruise operator into a prominent player in the luxury cruise industry, recognised for its specialised itineraries and high-quality service.

Bridgepoint acquired Compagnie du Ponant in 2012 (for ‘several hundred millions’). They oversaw the company’s expansion, including the commissioning of Le Lyrial, which was delivered in April 2015.

Bridgepoint Group was founded in 1984 as NatWest Equity Partners. The firm underwent a management buyout in 2000, and rebranded as Bridgepoint Capital. Since then, Bridgepoint has evolved into a leading private equity firm, focusing on industry, financial services and healthcare. It manages more than €67 billion in assets spread across Europe, North America, and Asia. In August 2024, Bridgepoint expanded its infrastructure capabilities by merging with Energy Capital Partners (ECP), an American investment firm specialising in energy sector assets.

During Bridgepoint’s ownership, the high-end cruise industry was booming, with increasing interest in small-ship, expedition-style voyages. Bridgepoint recognised that Ponant could differentiate itself with intimate, luxurious vessels capable of accessing remote destinations (e.g., Antarctica, the Arctic, and small Mediterranean ports).

After managing the introduction of the new fleet, Bridgepoint sold the company to Groupe Artémis, the investment holding of French billionaire François Pinault (owner of Kering, which owns the brands Yves Saint Laurent, Gucci, Balenciaga and Alexander McQueen, etc.). The sale price was around €400 million, significantly higher than the estimated purchase price by Bridgepoint. Since then Ponant has launch the Explorer-class ships, starting with Le Lapérouse.

How about some useful jargon?

- Aft: The area near the ship’s stern (Fore is toward the bow or front, and Amidship is the middle section of a ship)

- Bow: The front of the ship

- Bridge: The area of the ship where the captain and crew control and manage the vessel

- Cabin: Onboard room, also known as a stateroom

- Decks: The floors of the ship’s structure

- Galley: The ship’s kitchen

- Hull: The main body of the ship

- Port: The left side of the ship when facing the bow

- Starboard: The right side of the ship when facing the bow

- Stern: The extreme rear of the ship

- Beam: The broadest part of the ship’s hull

- Berth: The “parking spot” where the ship docks (sometimes called a “bed” on a cruise ship)

- Cabin steward: The crew member who cleans and maintains your stateroom

- Captain: The commander of the ship

- Cruise director: The person responsible for managing onboard entertainment, activities and events

- Leeward: The side of a ship that’s sheltered from the wind

- Mooring: The item used to secure the ship at the port

- Muster station: The area where passengers gather in case of an emergency

- Stem: Extreme forward part of a ship’s bow

- Tender: A small boat that takes passengers to the shore if the ship is at anchor

- Wake: The trail of waves seen at the rear of a ship as it moves forward

- Windward: The windier side of a ship.

Where do some of these terms come from? According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, words like ‘starboard’ and ‘port’, for example, go back to the early days when sailors used a steering oar to control their vessel. Since most sailors were right-handed, they placed the steering oar through or over the right side of the stern. Sailors began to call the right side the steering side, or the starboard. Starboard combines the Old English words ‘stéor‘, which meant steer, and ‘bord’, which meant the side of the boat.

‘Bridge’ has its origins in a beam or log laid down for crossing over a ravine or river. Bridge in steam-vessels was the connection between the paddle-boxes, from which the officer in charge directed the motion of the vessel. This elevated position helped oversee navigation, maneuvering, and communication with the crew below. Over time, as ships evolved, this structure became a dedicated command centre, but the name ‘bridge’ remained.

‘Mast‘ was a “long pole on a ship, secured as the lower end to the keel, to support the yards, sails, and rigging in general”. The single mast of an old ship was the boundary between the quarters of the officers and those of the crew. In all large vessels the masts were composed of several lengths, called lower mast, topmast, and topgallantmast. The royalmast is now made in one piece with the topgallantmast. A mast consisting of a single length is called a pole-mast. In a full-rigged ship with three masts, each of three pieces, the masts are distinguished as the foremast, the mainmast, and the mizzenmast, and the pieces as the foremast (proper), foretopmast, foretopgallantmast, etc. In vessels with two masts, they are called the foremast and mainmast, and in vessels with four masts, the aftermast is called the spanker-mast or jigger-mastearly.

‘Stern‘ dates from the 13th century, meaning “hind part of a ship”, where the helm and rudder were, and probably came from a Scandinavian source, such as Old Norse ‘stjorn’ meaning “a steering”. ‘Bow‘ is the “forward part of a ship”, beginning where the sides trend inward, and dates from mid-14th century, possible from Old Norse bogr. ‘Stem‘ comes from Old English ‘stemn’ or ‘stefn’ meaning “trunk of a tree or shrub”, and the word was used for the post at the bow of a ship, hence the word came to mean “front of a ship” generally by 1550s. That sense is preserved in the phrase stem to stern, which is originally nautical meaning “along the full length” (of a ship), and is attested from 1620s.

‘Wake‘ as a “track left by a moving ship” dates from the 1540s, and perhaps comes from Old Norse ‘vök’ or ‘vaka’ meaning “hole in the ice”. The sense perhaps evolved via “track made by a vessel through ice”.

And finally ‘Captain‘ dates from the late 14th century, meaning “a leader, chief, one who stands at the head of others”, from Old French ‘capitaine’, and the Late Latin ‘capitaneus’ meaning “chief”. The military sense of “officer who commands a company” (the rank between major and lieutenant) is from 1560s. The naval sense of “officer who commands a man-of-war” is from 1550s, and was extended to “master or commander of a vessel of any kind” by 1704.

Le Lyrial - what does it all mean?

Ponant defines Le Lyrial as “one of a new generation of intimately sized cruise ships”, and provides some basic information on the ship itself, namely:-

- Length – 142 meters

- Beam – 18 meters

- Draft – 4.7 meters

- Cruise speed – 14 knots

- Ice Class – 1C

- Classification – Bureau Veritas

- Flag – France

- Guest decks – 6

- Guest capacity – 264

- Zodiacs – 11

- Gross tonnage – 10,944 UMS

- Electric motors – 2 x 2300 kW

- Installed power – 6400 kW

- Construction – Fincantieri, Ancône, Italy

But what do these characteristics and parameters mean in reality?

We all think we know what ‘length’ means, but for a ship this often means the distance between where the forward part (the bow) cuts the waterline and the rudder post. Often the rudder is fully submerged beneath the hull, and is connected to the steering mechanism by a rudder post that comes up through the hull to the deck. As far as I know the 142 meters refers to “length overall” (LOA) which is the important measurement for berthing, or the maximum length of the ship between the ship’s extreme points.

Even a simple idea such as waterline, the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water, can hide some surprises (see waterline length). Generally a waterline can be any line on a ship’s hull that is parallel to the water’s surface when the ship is afloat in a level trimmed (horizontally balanced) position. Hence, waterlines are a class of “ships lines” used to denote the shape of a hull in naval architecture plans. It is not the same as the load line (Plimsoll line), which is the waterline indicating the legal limit to which a ship may be loaded for specific water types and temperatures in order to safely maintain buoyancy. And for vessels with displacement hulls, the hull speed is defined by, among other things, the waterline length.

Beam is the width of the ship measured at the widest point of the nominal waterline. This looks reasonable, but there is no defined ‘nominal’, and in fact a beam of a ship can be the distance between planes passing through the outer sides of the ship, which might not be so obvious if the hull deck is slightly convex. It could also mean the distance between the permanently fixed parts of the hull, or the maximum width where the hull intersects the surface of the water (but even this will depend upon the load, ballast, etc. being carried by the ship).

Draft is the vertical distance from the bottom of the keel to the waterline, which we now know will vary with length and beam. However, draft is most important when determining the minimum water depth for safe passage of a vessel and to calculate the vessels displacement (obtained from ships stability tables) so as to determine the mass of cargo on board. Again here this refers to the general issue of ship stability, and where the stability report for a ship will contain a variety of tables and graphs allowing the captain to read how high the centre of gravity must be for the vessel to safely sailing under known and well defined load conditions.

However, there are a number of additional measures that also define a ship.

Complement/Ships Company – The full number of people required to operate a ship, includes officers and crew, but not including passengers.

Tonnage – is a measure of a ship’s cargo carrying capacity. Merchant ships often mention gross tonnage, which is a nonlinear measure of a ship’s overall internal volume in cubic meters, and not in units of mass or weight. There is also net tonnage, expressed in cubic meters. These definition are different from gross register tonnage and net register tonnage (both obsolete units). However, there is also deadweight tonnage, which is a measure of how much weight a ship can carry, and includes cargo, fuel, fresh water, ballast water, provisions, passengers, and crew. And there is the idea of the number of items a ship can carry, in Twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU). This is in fact a measure of the number of containers a ship can carry.

In the description of Le Lyrial we see a mention of “gross tonnage” as 10,944 UMS. This is the Universal Measurement System (UMS), which is a measure of a ship’s size, calculated by the volume of all enclosed spaces on the ship. This is an international convention that entered into force in 1982, and applies to all ships built after that year. The Convention meant a transition from the traditionally used terms gross register tons and net register tons to gross tonnage and net tonnage. This is important because gross tonnage is the basis for manning regulations, safety rules and registration fees, and both gross and net tonnages are used to calculate port dues. The “volume of all enclosed spaces” means net tonnage is produced by a formula which is a function of the moulded volume of all cargo spaces of the ship.

Gross tonnage UMS is expressed as a figure without units. For example, the Panama Canal uses the UMS to calculate tolls. The name “tonnage” actually derives from the old English word ‘tun’ meaning barrel. This expression of the “size” of ship is only really useful for the layman because if the figure is bigger, the ship is bigger. But the story does not end there. A variety of parameters such as draft, beam, length overall, gross tonnage, deadweight tonnage etc. are taken into consideration while designing and constructing a merchant ship. The designer must think about where the ship will go, and can it traverse the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal, i.e. can the ship smoothly transit through the narrowest and shallowest areas of the canal, in both fully loading and unloading conditions. For example Panamax and New Panamax are terms used for ships that are designed to travel through the Panama Canal. Aframax is for certain types of oil tankers, Chinamax and Handyman are for certain types of bulk carriers, and Capesize is for largest dry cargo ships which are too large to transit the Suez Canal or Panama Canal, and so have to pass either Cape Agulhas or Cape Horn to traverse between oceans, and so on… These cargo ships are compared in TUE or the number of containers, and can range from 500 TUE to 25,000 TUE.

Displacement – is the weight or mass of the vessel, at a given draft. There is the lightweight displacement (LWD) or the weight or mass of the ship excluding cargo, fuel, ballast, stores, passengers, and crew, but if necessary including the water in the boilers to steaming level. And there is the “loadline displacement”, which the weight or mass of the ship loaded to the load line (Plimsoll line). Displacement is usually expressed in tonne (metric unit), however ships built for the US will usually be in long tons.

Shaft Horsepower – is the amount of mechanical power delivered by the engine to a propeller shaft. This is (again) not an easy definition since the power of an engine may be measured or estimated at several points in the transmission of the power from its generation (engine) to its application (propeller). There is the nominal horsepower which depends on the size of the engine and piston speed for normal operation (often mention as being with a normal “head of steam”). This is different from the theoretical capability of the engine. But there is also the idea of brake horsepower which is the power delivered directly to and measured at the engine’s crankshaft, and is the nominal horsepower minus frictional losses within the engine (bearing drag, rod and crankshaft windage losses, oil film drag, etc). And there is the shaft horsepower, which is the power delivered to and measured at the output shaft of the transmission, so minus frictional losses in the transmission (bearings, gears, oil drag, windage, etc.). And finally there is effective or true horsepower delivered to the propeller, often mentioned as wheel horsepower, and is the shaft horsepower minus frictional losses in the universal joint/s, differential, wheel bearings, etc. that link the shaft to the propeller. And just to confuse things more, designers and engineers will often express horsepower as simply theoretical performance targets. We know that 1 horsepower is equivalent to 746 Watts, but what the statement “2 x 2300 kW” means is totally unclear.

On one minor document about Le Lyrial there is a mention of the incomprehensible “DD-GG 4 x 8L20 Wärtsilä”. Which actually refers to the ship’s power generation system, comprising four Wärtsilä 8L20 diesel generator sets. Each 8L20 engine is an eight-cylinder, in-line, four-stroke diesel engine produced by Wärtsilä, designed for marine applications. These engines are known for their compact size, reliability, and fuel flexibility, capable of operating on various fuels including heavy fuel oil (HFO), marine diesel oil (MDO), and ultra-low sulfur fuel. Each 8L20 engine delivers an output of approximately 1,600 kW at 1,000 rpm (contributing to a total installed electrical power of 7,200 kW). In this context, “DD-GG” stands for “Diesel Generator Groups,” indicating the use of diesel engines coupled with generators to produce electrical power for the vessel. The “4 x 8L20” just means that there are four units of the 8L20 engine model installed.

Another incomprehensible designation is “DD-GG 1 x V1712T3TE Isotta Fraschini”. This refers to a specific diesel generator set produced by Isotta Fraschini Motori, an Italian engine manufacturer. This generator set is utilized as an auxiliary power source. In this context, “DD-GG” again stands for “Diesel Generator Group,” indicating its role in providing electrical power. The model “V1712T3TE” specifies the engine type, which delivers a power output of 926 kW at 1,500 rpm.

What does 'Ice Class - 1C mean'?

The reality is that there is no single, universal ice classification system that applies worldwide. Instead, different maritime authorities and classification societies have developed their own systems, often tailored to specific regions. However, there are some global frameworks that help standardise ice-class ratings across different systems.

The International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) introduced the Polar Class (PC1 – PC7) system, which is the closest thing to a global standard. This system is used by several major classification societies (DNV, Lloyd’s Register, ABS, etc.) and aligns with the IMO Polar Code for ships operating in Arctic and Antarctic waters.

There are historical reasons for not having a global stand, and there are also technical reasons. Firstly, it’s argued that different regions (e.g. Arctic, Antarctic, Baltic, and Russian Arctic, etc.) have unique ice conditions. Secondly, some standards focus on the needs of particular types of ships (e.g. cargo ships, polar explorers, etc.).

IACS Polar Class Levels

- PC1 – Year-round operation in all polar ice conditions (strongest).

- PC2 – Year-round operation in multi-year ice.

- PC3 – PC5 – Can operate in various levels of first-year ice, with decreasing strength.

- PC6 & PC7 – Mostly for summer/autumn operations in first-year ice (weakest).

The Finnish-Swedish Ice Classes (FSICR) classifies Class IC for navigation in the thinnest ice.

What does 'Classification - Bureau Veritas' mean?

Bureau Veritas, is a globally recognised classification society, which assesses and certifies ships, offshore structures, and other industrial assets to ensure they meet specific safety, environmental, and regulatory standards.

Classification Societies conduct initial surveys, periodic inspections, and certification renewals to maintain classification status. Many countries and insurers require classification from recognised bodies like Bureau Veritas to certify that a vessel or structure meets international standards. Generally the classification societies follow international conventions such as SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea), MARPOL (Marine Pollution), and IMO (International Maritime Organization) regulations.

As far as I know the specific inspections and the inspection routines are not publicly disclosed for Le Lyrial. However, inspections would normally include:-

- Annual Surveys: Comprehensive inspections conducted every year to verify the ship’s structural integrity, machinery, and safety equipment.

- Intermediate Surveys: More detailed than annual surveys, these occur approximately every two to three years, focusing on specific areas such as hull condition and onboard systems.

- Special Surveys: Extensive inspections performed every five years, requiring thorough examinations of the vessel’s structure, machinery, and systems.

- Dry Docking: Scheduled at intervals (often aligned with special surveys), where the ship is taken out of the water for underwater hull inspection, maintenance, and repairs.

What does 'Flag - France' mean?

When a ship flies the flag of a particular country (e.g., France for Le Lyrial), it means it is registered under that country’s flag state.

The term ‘flag state’ has a specific legal and technical meaning in maritime law. It refers to the country under whose laws a ship is registered and operates. This country exercises jurisdiction and regulatory oversight over the vessel, no matter where it is in the world. The ‘flag state’ also has jurisdiction over the crew working aboard the ship. This means that crew employment, labour rights, qualifications, and working conditions are governed by the laws of the ship’s flag state, even if the crew members themselves have different nationalities.

Flying a particular flag brings with it obligations and responsibilities, as well as legal and financial advantages.

Legal and Regulatory Oversight

- The ship must comply with the laws and regulations of its flag state regarding safety, environmental standards, labor rights, and operational procedures.

- The flag state is responsible for ensuring the ship adheres to international conventions like SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea), MARPOL (Marine Pollution), STCW (Seafarer Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping), and MLC (Maritime Labour Convention).

Classification and Certification

- Ships must be inspected and certified under the maritime administration of the flag state (e.g., France’s Bureau Veritas and the Direction des Affaires Maritimes).

- The flag state can delegate inspections to recognised classification societies (like Bureau Veritas, Lloyd’s Register, DNV-GL, etc.).

Taxation and Financial Implications

- Many shipowners register under “flags of convenience” (e.g., Panama, Liberia, Marshall Islands) because they offer lower taxes, less strict regulations, and cheaper labour.

- France is a traditional or national flag state, meaning its regulations may be stricter, but it can provide economic benefits such as subsidies or advantages in certain trade agreements.

Jurisdiction and Law Enforcement

- The ship is considered sovereign territory of its flag state while in international waters.

- The flag state has the right to enforce laws onboard, including labour conditions, security, and criminal matters.

Port State Control and Access

- Some flags of convenience are subject to more frequent inspections under the Paris MoU (Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control) due to safety concerns.

- Ships flying high-standard flags (such as France, Norway, or the UK) may face fewer port state control inspections when docking in foreign ports.

Military and Protection Rights

- If a ship is in distress, the navy or coast guard of its flag state may provide assistance.

- In times of war or conflict, the flag state may requisition the ship for military or logistical use.

Crew Nationality and Labor Rules

- Some flag states require a certain percentage of the crew to be of the same nationality (France requires a minimum of 35% French/EU seafarers under certain conditions).

- Labour rights and minimum wage laws often align with ILO (International Labour Organization) regulations, but can differ by flag state.

Le Lyrial flies the French flag, which means:-

- It is registered in France and must comply with French maritime regulations.

- Bureau Veritas (or another recognised body) ensures it meets safety and environmental standards.

- It benefits from French protection and economic support programs.

- Its crew must comply with French labour laws, which are typically stricter than those of flags of convenience.

However, the French flag is a high-quality flag, meaning ships registered under it enjoy a strong reputation for safety, environmental compliance, and labour standards. Ships flying the French flag often face fewer delays in international ports because they are not subject to heightened Port State Control inspections (unlike flags of convenience such as Panama or Liberia). Ships registered in France benefit from subsidies and financial aid under the French International Register, and they can receive state support for investments in ship maintenance, environmental compliance, and crew employment. The French International Register (RIF) also offers tax reductions on corporate profits, making it more competitive compared to traditional French corporate taxation. There are exemptions from employer social security contributions for French and European seafarers.

EU-flagged ships have preferential access to certain contracts, particularly for government-funded or protected shipping routes. The Paris MoU “White List” includes France, meaning ships under the French flag are less likely to face time-consuming inspections in European ports.

Why is Le Lyrial registered in Wallis and Futuna?

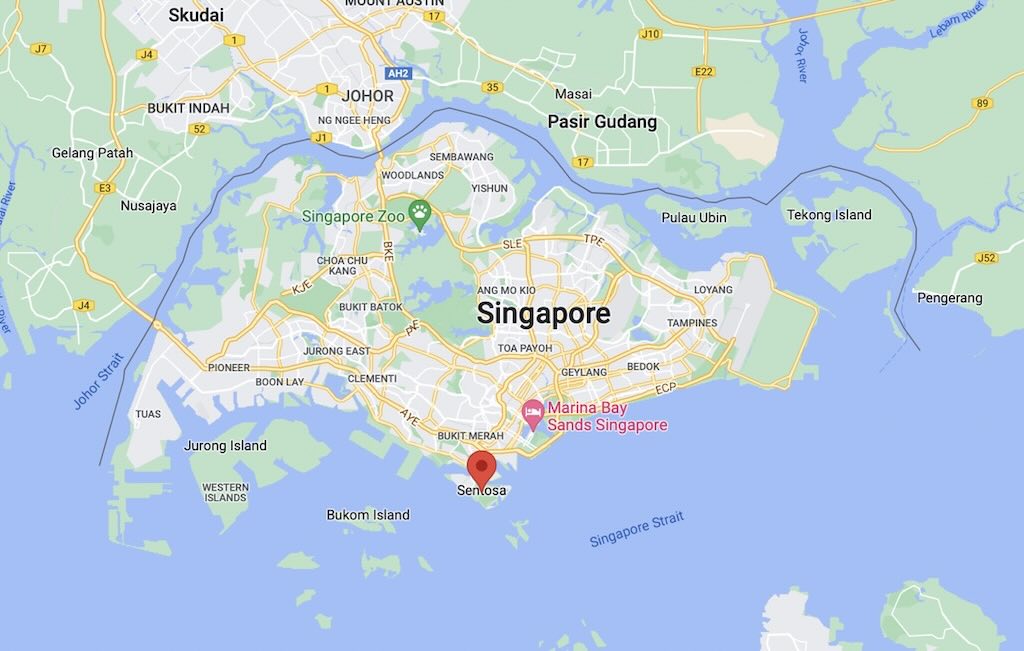

It is my understand that all Ponant ships are resisted in Wallis and Futuna, a French island collectivity in the South Pacific, situated between Tuvalu to the northwest, Fiji to the southwest, Tonga to the southeast, Samoa to the east, and Tokelau to the northeast.

What this means:-

- Wallis and Futuna is not part of the EU, and only operates under French maritime laws.

- The territory has its own labour code, which is less stringent than that of metropolitan France. This flexibility can result in reduced labour costs for shipowners. However, ships registered in Wallis and Futuna are still required to adhere to international standards set by the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) of 2006.

- There are corporate tax incentives that provide a full refund of employer contributions over two years, a 50% reduction on import levies for project-related materials and equipment, and assistance covering 30% of interest costs on project-related loans.

- The Girardin Law is a French Overseas Tax Relief Scheme (extended until end 2025). This scheme allows French taxpayers to reduce their taxes by investing in materials and equipment used in overseas industries or crafts projects, as well as in housing developments. Up to 35.87% of the total investment can be financed under this tax relief scheme.

- Wallis and Futuna-registered ships can access French maritime infrastructure and diplomatic support.

While specific ownership details of UMS are not publicly available, its close operational relationship with PONANT suggests a significant partnership between the two companies. Uvéa Marine Services (UMS) serves as the primary crewing agency for all Ponant ships. At different times I’ve seen UMS recruiting crew members across Ponant’s fleet for positions in Deck, Engine, Hotel, Medical, Production (Speakers, Naturalists), and Expedition departments.

I’ve found it surprising difficult to find the exact financial rules operating in Wallis and Futuna, but one source mentioned that:-

- Companies operating in Wallis and Futuna are exempt from corporate income tax.

- Individuals, including business owners and employees, are not subject to personal income tax.

- Gains from the sale of assets or investments are not taxed.

- Instead of a Value Added Tax (VAT), Wallis and Futuna implement a Territorial Consumption Tax applied to goods and services consumed within the territory. Businesses are responsible for collecting and remitting the TCT, and while specific rates may vary, this system can be advantageous compared to VAT regimes in other jurisdictions.

- There is potential funding of up to 40% of investment costs, with a maximum limit of 4 million XPF, to support business establishment and expansion.

- Total reimbursement of employer contributions for a two-year period, reducing labour costs for new businesses.

- The absence of complex tax obligations simplifies compliance and reduces administrative burdens, allowing companies to focus more on their core operations.

How can Le Lyrial safely navigate Artic and Antarctic waters?

Firstly, any ship navigating in open waters must have equipment for marine navigation, communication, and safety at sea. Above, I’ve included two decent walkthrough videos of cruise ship control rooms. And below I’ve added a few links to more detailed descriptions.

Navigation Equipment and Resources Used Onboard in a Modern Ships (Part 1)

Navigation Equipment

- Gyrocompass and Magnetic Compass: For determining the ship’s heading.

- Radar Systems: At least one radar system, but many ships have multiple systems, including ARPA (Automatic Radar Plotting Aids) for collision avoidance.

- Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS): Primary navigation system with updated digital charts, but paper charts may also be required as a backup. Check out the video What is an Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS)

- Global Positioning System (GPS): For determining the ship’s position.

- Echo Sounder: For measuring water depth below the ship.

- Speed and Distance Log Device: For recording the ship’s speed and distance travelled.

Communication Equipment

- Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS): For emergency communications, including:

- VHF and MF/HF radios.

- Satellite communication systems (e.g., Inmarsat).

- Digital Selective Calling (DSC).

- NAVTEX receiver for weather and safety information.

- Emergency Position-Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB).

- Search and Rescue Transponder (SART).

Safety Equipment

- Bridge Alarm Management System (BAMS): Alerts crew to navigation and equipment issues.

- Steering Gear Control System: Includes manual and automatic systems.

- Voyage Data Recorder (VDR): Records bridge activity and critical data for accident investigation.

- Automatic Identification System (AIS): For vessel identification and tracking.

Environmental and Specialized Equipment

- Ice Navigation Equipment (for polar expedition ships):

- Ice radar or specialized radar overlays for detecting sea ice.

- Polar Code-compliant tools for safe operation in icy waters.

- Weather Monitoring Instruments:

- Anemometer for wind speed/direction.

- Barometer for atmospheric pressure.

Additional Equipment (Polar Ships)

For ships operating in polar regions, the Polar Code (adopted by the IMO) adds specific requirements, such as:

- Ice-strengthened hull classification.

- Extra communication systems for remote regions.

- Additional lifesaving appliances (thermal suits, ice-escape equipment).

Documentation and Records

- Logbooks: Official logs for navigation, weather, and events.

- Passage Plans: Pre-prepared routes and contingencies.

- Certificates: Compliance with SOLAS, Polar Code, and other relevant maritime standards.

What is ice radar?

Do you know the history of cruise ships?

The birth of leisure cruising began with the formation of the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company in 1822 (P&O). The company started out as a shipping line with routes between England and the Iberian Peninsula, adopting the name Peninsular Steam Navigation Company. It won its first contract to deliver mail in 1837. In 1840, it began mail delivery to Alexandria, Egypt, via Gibraltar and Malta. The company was incorporated by Royal Charter the same year, becoming the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company.

The company began offering luxury cruise services in 1844, advertising sea tours to destinations such as Gibraltar, Malta and Athens, sailing from Southampton. The forerunner of modern cruise holidays, these voyages were the first of their kind, and P&O Cruises has been recognised as the world’s oldest cruise line. The company later introduced round trips to destinations such as Alexandria and Constantinople. It underwent a period of rapid expansion in the latter half of the 19th century, commissioning larger and more luxurious ships to serve the steadily expanding market. Notable ships of the era include the SS Ravenna built in 1880, which became the first ship to be built with a total steel superstructure, and the SS Valetta built in 1889, which was the first ship to use electric lights.

Some sources mention Francesco I, flying the flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Italy), as the first cruise ship. She was built in 1831 and sailed from Naples in early June 1833, preceded by an advertising campaign. The cruise ship was boarded by nobles, authorities, and royal princes from all over Europe. In just over three months, the ship sailed to Taormina, Catania, Syracuse, Malta, Corfu, Patras, Delphi, Zante, Athens, Smyrna, Constantinople, delighting passengers with excursions and guided tours, dancing, card tables on the deck and parties on board. However, it was restricted to the aristocracy of Europe and was not a commercial endeavour.

The cruise of the German ship Augusta Victoria in the Mediterranean and the Near East from 22 January to 22 March 1891, with 241 passengers including Albert Ballin and wife, popularised the cruise to a wider market. Christian Wilhelm Allers published an illustrated account of it as Backschisch (Baksheesh).

The first vessel built exclusively for luxury cruising, was Prinzessin Victoria Luise of Germany, designed by Albert Ballin, general manager of Hamburg-America Line (HAPAG). The ship was completed in 1900. The practice of luxury cruising made steady inroads on the more established market for transatlantic crossings. In the competition for passengers, ocean liners added luxuries (Titanic being the most famous example) such as fine dining, luxury services, and staterooms with finer appointments. In the late 19th century, Albert Ballin, director of the Hamburg-America Line, was the first to send his transatlantic ships out on long southern cruises during the worst of the winter season of the North Atlantic. Other companies followed suit. Some of them built specialised ships designed for easy transformation between summer crossings and winter cruising.

In 1896, there were three luxury liners for transportation, for the Europe to North America trip. These were European-owned. In 1906, the number had increased to seven. The British Inman Line owned City of Paris, the Cunard Line the Lucania. The White Star Line owned Majestic and Teutonic.

From luxury ocean liners to “megaship” cruising

With the advent of large passenger jet aircraft in the 1960s, intercontinental travellers switched from ships to planes sending the ocean liner trade into a terminal decline. Certain characteristics of older ocean liners made them unsuitable for cruising duties, such as high fuel consumption, deep draught preventing them from entering shallow ports, and cabins (often windowless) designed to maximise passenger numbers rather than comfort.

Ocean liner services aimed at passengers ceased in 1986, with the notable exception of transatlantic crossings operated by the British shipping company Cunard Line, catering to a niche market of those who appreciated the several days at sea. In an attempt to shift the focus of the market from passenger travel to cruising with entertainment value, Cunard Line pioneered the luxury cruise transatlantic service on board the Queen Elizabeth 2 ocean liner. International celebrities were hired to perform cabaret acts onboard and the crossing was advertised as a vacation in itself. Queen Elizabeth 2 also inaugurated “one-class cruising” where all passengers received the same quality berthing and facilities. This revitalized the market as the appeal of luxury cruising began to catch on, on both sides of the Atlantic. The 1970s television series Love Boat, helped to popularise the concept as a romantic opportunity for couples.

Another ship to make this transition was SS Norway, originally the ocean liner SS France and later converted to cruising duties as the Caribbean’s first “super-ship.”

Contemporary cruise ships built in the late 1980s and later, such as Sovereign-class which broke the size record held for decades by Norway, showed characteristics of size and strength once reserved for ocean liners. The Sovereign-class ships were the first “megaships” to be built for the mass cruising market, they also were the first series of cruise ships to include a multi-story atrium with glass elevators. And they also had a single deck devoted entirely to cabins with private balconies instead of ocean-view cabins. Other cruise lines soon launched ships with similar attributes, such as the Fantasy-class, leading up to the Panamax–type Vista-class, designed such that two thirds of the ocean-view staterooms have verandas. As the veranda suites were particularly lucrative for cruise lines, something which was lacking in older ocean liners, recent cruise ships have been designed to maximise such amenities and have been described as “balcony-laden floating condominiums”.

Until 1975-1980, cruises offered shuffleboard, deck chairs, “drinks with umbrellas and little else for a few hundred passengers.” After 1980, they offered increasing amenities. As of 2010, city-sized ships have dozens of amenities. There have been nine or more new cruise ships added every year since 2001, including the 11 members of the Vista-class, and all at 100,000 GT or greater. The only comparable ocean liner to be completed in recent years has been Cunard Line’s Queen Mary 2 in 2004. Following the retirement of her running mate Queen Elizabeth 2 in November 2008, Queen Mary 2 is the only liner operating on transatlantic routes, though she also sees significant service on cruise routes.

Queen Mary 2 was for a time the largest passenger ship before being surpassed by Royal Caribbean International’s Freedom-class vessels in 2006. The Freedom-class ships were in turn overtaken by RCI’s Oasis-class vessels which entered service in 2009 and 2010. A distinctive feature of Oasis–class ships is the split “open-atrium” structure, made possible by the hull’s extraordinary width, with the 6-deck high “Central Park” and “Boardwalk” outdoor areas running down the middle of the ship and verandas on all decks.

In two short decades (1988-2009), the largest class cruise ships have grown a third longer (268 m to 360 m), almost doubled their widths (32.2 m to 60.5 m), doubled the total passengers (2,744 to 5,400), and tripled in weight (73,000 GT to 225,000 GT). Also, the “megaships” went from a single deck with verandas to all decks with verandas.

The golden age of ocean liners has faded, replaced by cruise ships.

Cruise lines have a dual character, they are partly in the transportation business, and partly in the leisure entertainment business. A duality that carries down into the ships themselves, which have both a crew headed by the ship’s captain, and a hospitality staff headed by the equivalent of a hotel manager.

Historically, the cruise ship business has been volatile. The ships are large capital investments with high operating costs. A persistent decrease in bookings can put a company in financial jeopardy. Cruise lines have sold, renovated, or renamed their ships to keep up with travel trends. The cruise lines operate their ships virtually 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 52 weeks a year. A ship which is out of service for routine maintenance means the loss of tens of millions of dollars. If the maintenance is unscheduled, it can result, potentially, in thousands of dissatisfied customers.

A wave of failures and consolidations in the 1990s has led to many cruise lines to be bought by much larger holding companies, and now operates as “brands” within larger holding corporations, much as a large automobile company holding several makes of cars. Brands exist partly because of repeat customer loyalty, and also to offer different levels of quality and service. For instance, Carnival Corporation & plc owns both Carnival Cruise Line, whose former image were vessels that had a reputation as “party ships” for younger travellers, but have become large, modern, yet still profitable, and Holland America Line, whose ships cultivate an image of classic elegance. In 2004, Carnival Corporation had merged Cunard’s headquarters with that of Princess Cruises in Santa Clarita, California so that administrative, financial and technology services could be combined, ending Cunard’s history where it had operated as a standalone company (subsidiary) regardless of parent ownership. However, Cunard did regain some independence in 2009 when its headquarters were moved to Carnival House in Southampton.

The common practice in the cruise industry in listing cruise ship transfers and orders is to list the smaller operating company, not the larger holding corporation, as the recipient cruise line of the sale, transfer, or new order. In other words, Carnival Cruise Line and Holland America Line. for example, are the cruise lines from this common industry practice point of view; whereas Carnival Corporation & plc and Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd., for example, can be considered holding corporations of cruise lines. This industry practice of using the smaller operating company, not the larger holding corporation, is also followed in the list of cruise lines and in member-based reviews of cruise lines.

Some cruise lines have specialties; for example, Saga Cruises only allows passengers over 50 years old aboard their ships, and Star Clippers and formerly Windjammer Barefoot Cruises and Windstar Cruises only operate tall ships. Regent Seven Seas Cruises operates medium-sized vessels (smaller than the “megaships” of Carnival and Royal Caribbean) designed such that 90% of their suites are balconies.

Several specialty lines offer “expedition cruising” or only operate small ships, visiting certain destinations such as the Arctic and Antarctica, or the Galápagos Islands.

What is the world market for cruises?

After COVID, the cruise industry has experienced a robust resurgence, with passenger numbers and market dynamics evolving across various geographical regions. In 2023, the cruise industry welcomed nearly 32 million passengers, surpassing 2019 figures by 7%. Projections for 2024 were for nearly 36 million passengers. The global cruise tourism market is anticipated to reach $45 billion by 2029, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8% from 2023 to 2029.

The largest market (~44% of all cruise itineraries) is the Caribbean & Bahamas. The trend is towards more luxury and shorter cruises (3-5 days).

The second largest market (~20% of global cruises) is the Mediterranean. The trend is towards longer, premium itineraries (9-11 days), driven by luxury and expedition cruises. There is an increased interest in cultural/historical routes and sustainable tourism initiatives.

The thirds market (~10-12%) is Northern Europe & Baltic Sea. The trend is for Norwegian fjords, Arctic cruises, and small-ship expedition cruises.

The fourth market (~8%) is Alaska and North America. Here the trend is to eco-tourism, LNG-powered ships, glacier viewing & wildlife cruises.

The fifth market (~7-9%), but the fastest growing, is Asia-Pacific. The trend is more luxury and premium small-ship with Japan & South Korea itineraries.

The sixth market (~5-7%) is Australia & South Pacific. The trend is for longer South Pacific itineraries (e.g. New Zealand, Tahiti).

The last major market (~3-5%) is South America & Antarctica. The trend is for expedition cruises, with many sell-out years in advance.

Certainly expedition & adventure cruises are increasingly popular, with around 70% growth from 2019 to 2023, especially in Antarctica and Arctic routes.

Also there are numerous trends in terms of type and size of ships.

Firstly, large/mega ships will be even more entertainment focussed, but also they will have to invest in cleaner technologies. In fact the LNG-powered is one example of the rapid transition to cleaner fuel and hybrid propulsion. More and more, ships will plug into port electricity instead of running engines. Also there are stricter European and Alaskan environmental laws in place.

Increasing demand for small, luxury exploration vessels, some with submarines and science labs onboard, but tariffs will be an obstacle.

Next there is also an increasing demand for smaller, all-suite vessels with personalised butler service, Michelin restaurants, and targeting small ports that large ships can’t access.

River & Hybrid Coastal Cruisers will become more intimate, slower-paced, with extended shore stays in places such as Mekong River (Vietnam/Cambodia).

Finally, there are the residential & long-stay cruise ships, targeting nomad workers & retirees, but it’s still a niche market due to high costs.

Despite negative press, in 2022, the cruise industry generated $138 billion for the global economy and supported 1.2 million jobs, surpassing pre-pandemic levels. In fact more than 80% of travellers who have cruised before said they would cruise again. And surprisingly cruising is no longer dominated by older generations. Millennials and Gen Z are increasingly choosing cruise vacations. Notably, 35% of cruise travellers are under 40, and 80% of those aged 29 to 44 plan to cruise again.

There are environmental concerns, namely, the need to invest in cleaner technologies and sustainable practices. Environmental groups are calling for stricter regulations and greater transparency to mitigate environmental impacts. And there is also the problem of overtourism in place such as Venice and Barcelona.

What about the pricing of cruises?

According to the Cruise Line Association (2014), price is the top motivator to take a cruise, followed by destinations/itineraries, then cruise company reputation.

When one looks at the pricing challenges and strategies of cruise lines in comparison with other segments of the travel industry, one might think that cruise lines are doing well. But, it’s not the case. Hotels and airlines report an annual occupancy of more than 70% and a load factor with 80-90%, respectively, to be considered financial successes. Although a cruise ship is usually regarded as a floating hotel, there are differences when it comes to occupancy. Empty cabins are problematic because of both revenue loss and operational loss. Operational loss may include loss in tipping (which makes up a big portion of many personnel’s income) which in turn makes it difficult for the company to keep experienced employees. And the loss of work morale makes the cruising experience for passengers less pleasurable. It is therefore very important to fill in every cabin as much as possible and that situation consequently makes pricing strategies in the cruise line industry even more critical.

Pricing in the cruise industry may not be the same as compared to the airline industry (the one that gave rise to revenue management in the first place), but it basically uses similar strategies like price differentiation and capacity allocation.

The topmost contributing factors in pricing decisions used by the cruise industry, start with building on previous sales, then seasonality, macro-political/economic factors, and finally customers feedback. Additionally, the cruise industry has also the following topmost objectives in pricing, firstly long-term profit, then growth, next keeping the loyalty of travel agents, creating curiosity for the product, and finally maintain the brand’s reputation.

How Cruise Companies Price Their Offerings: A Breakdown of Pricing Strategies

Cruise pricing is a dynamic process influenced by several key factors, including demand, seasonality, onboard spending, and targeted demographics. Below is a detailed look at how cruise companies determine prices.

Core Pricing Factors

A. Base Fare Pricing (Supply & Demand)

- Dynamic Pricing Model: Like airlines, cruise companies use yield management systems to adjust fares based on demand, booking windows, and occupancy rates.

- Early vs. Last-Minute Pricing:

- Early Booking (9-18 months out): Lower prices + promotions (e.g., free onboard credit, cabin upgrades)

- Last-Minute Deals (1-3 months out): Significant discounts to fill unsold cabins

- Cabin Type Influence: Suites and ocean-view rooms follow premium pricing, while interior cabins are the most budget-friendly.

B. Seasonal Pricing & Destination Demand

- High Season: Prices peak during summer, holidays, and school breaks (e.g., Caribbean in winter, Alaska in summer).

- Low Season (Wave Season Discounts): January–March promotions help fill early bookings.

- Itinerary-Specific Pricing:

- Exclusive destinations (Antarctica, Galápagos) → Higher base fares

- Competitive routes (Caribbean, Mediterranean) → More discounts

Revenue Maximization Strategies

A. Tiered Pricing & Upselling

- Cabin Categories:

- Basic (Interior) → Budget travellers

- Mid-tier (Balcony, Oceanview) → Comfort seekers

- Luxury (Suites, Themed Experiences) → High-spending travelers

- Upsell Tactics: Offer guests priority boarding, VIP lounges, and exclusive areas (e.g., The Haven by Norwegian, MSC Yacht Club) at a premium.

B. “Bait and Hook” Pricing Model

- Low Base Fare + High Onboard Spending

- Core Strategy: Keep cruise fares relatively low but maximize onboard revenue through add-ons and extras.

- Examples of Paid Extras:

- Specialty dining ($30–$100 per meal)

- Drink packages ($60–$100 per day)

- Shore excursions ($50–$500 per activity)

- Spa & wellness treatments ($150+)

- Wi-Fi access ($15–$40 per day)

- Gambling (casinos onboard generate huge revenue)

- Example:

- A $499/week cruise fare can easily turn into $1,500+ per person once all add-ons are included.

Targeted Promotions & Discounts

A. Loyalty & Membership-Based Pricing

- Frequent Cruisers Discounts: Returning customers from loyalty programs (e.g., Royal Caribbean’s Crown & Anchor) get priority deals.

- Exclusive Member Deals: Costco Travel & American Express cruise perks for premium credit card holders.

B. Family & Group Pricing

- Kids-Sail-Free Deals: Often applied to select sailings in the off-season.

- Group Discounts: 10+ travelers can receive free berths and onboard credit.

C. Resident & Military Discounts

- Some cruise lines offer state-specific discounts (e.g., Florida residents for Caribbean routes) and military perks.

Luxury & Premium Market Pricing

- Luxury Cruises (Seabourn, Silversea, Ritz-Carlton Yacht Collection):

- Fares start at $5,000+ per person but are often all-inclusive (drinks, gratuities, excursions).

- Expedition Cruises (Antarctica, Arctic):

- High-cost due to small ships, remote access, and specialized equipment ($10,000–$20,000 per person).

Future Trends in Cruise Pricing

- AI-Powered Pricing: Real-time tracking adjusts fares based on competitor prices, weather, and booking trends.

- Subscription-Based Pricing: Some cruise lines are testing “unlimited cruise passes” for frequent travellers.

- Sustainable Pricing Models: Carbon offsetting fees & eco-friendly ship surcharges emerging.

What's life like on board for a cleaner?

I work as a cleaner aboard Le Lyrial, a luxury expedition yacht with 122 staterooms and suites. My job is demanding, but it allows me to travel while supporting my family back home. Though guests enjoy an experience of elegance and refinement, my work behind the scenes is highly structured and follows strict procedures.

Each shift is divided into morning service, midday touch-ups, and evening turndown service. The number of times I enter a room depends on guest activity and whether they have requested reduced service.

Morning Service (Full Cleaning)

This is the most intensive cleaning session and is performed while guests are at breakfast or on excursions.

Ventilation & Inspection

I enter with gloves and a fresh set of microfiber cloths, opening the balcony door (weather permitting) to ventilate the room.

I inspect for any requests left by guests or any maintenance issues (e.g. malfunctioning lights, plumbing issues).

Bed Maintenance

Strip used linens and replace them with fresh sheets.

Smooth out the duvet, ensuring the corners are tucked neatly.

Arrange decorative pillows as per standard room layout.

Dusting & Surface Cleaning

Wipe all surfaces with an anti-static microfiber cloth and a mild disinfectant spray.

Sanitize frequently touched areas (door handles, remote controls, telephone).

Polish glass surfaces with a streak-free cleaner.

Bathroom Sanitization

Disinfect all surfaces, including the sink, mirror, toilet, and shower.

Scrub and rinse the shower walls and floor.

Replace towels:

2 large bath towels

2 hand towels

2 washcloths

1 bath mat

Restock toiletries:

Shampoo, conditioner, body wash (branded Ponant collection)

Shower cap

Cotton pads and swabs

Mini-Bar & Beverage Restocking

Water Bottles: Each cabin receives two 500ml bottles of still water and two of sparkling water per day.

Coffee Capsules: I restock up to four Nespresso capsules daily (2 regular, 1 decaf, 1 espresso intensity 8) unless guests request more.

Tea Selection: Refresh the supply of black tea, green tea, and herbal infusions.

Check and replace used sugar, sweeteners, and creamers.

Floor Care

Vacuum carpets or mop hard flooring, moving furniture as needed.

Trash & Final Touches

Empty bins and replace liners.

Arrange the room to its original state.

Refill room spray with Ponant’s signature scent.

Make minor bed adjustments (if guests have used the bed).

Replace used towels if necessary.

Replenish drinking water if empty.

Spot-clean visible dirt on surfaces.

Empty bins if they contain food waste.

Turn Down the Bed

Remove decorative pillows and store them in the closet.

Fold back the duvet to create a welcoming look.

Refresh Towels & Toiletries

Replace used hand towels.

Restock shower essentials if needed.

Mini-Snack & Beverage Replenishment

Place a small Ponant-branded chocolate on each pillow.

Replace empty water bottles with one still and one sparkling for overnight use.

Lighting & Atmosphere

Close the curtains and dim the lights.

Adjust the air conditioning to 22°C (guest preference permitting).

Accommodation & Living Conditions

I share a cabin with one to three other cleaners depending on ship occupancy and staffing levels.

Our cabin is located on the lower crew deck, near the laundry and storage areas.

The space is small but functional, featuring bunk beds, a wardrobe, and a small shared desk.

We have a shared bathroom among several cabins, which is cleaned daily by designated crew members.

There is no window, but we have air conditioning and a small fan for air circulation.

Storage is limited, so we keep only essential belongings onboard.

Crew Life: Food, Entertainment, and Social Dynamics

Meals: Crew meals are served in a separate cafeteria and follow a rotating weekly menu. The food is simple but sufficient, usually consisting of rice, vegetables, and a choice of fish, chicken, or beef. There are occasional themed meals celebrating different nationalities aboard.

Entertainment: The ship provides a small crew lounge with a TV, board games, and a wi-fi hotspot (limited and slow). Occasionally, on longer voyages, there are crew parties with music and snacks.

Relationships with Other Crew Groups: Housekeeping staff work closely with the laundry team and maintenance workers to ensure smooth operations. While we have limited interaction with officers, the cruise director and hotel manager oversee our department. Relationships with higher-ranking crew members are formal, but within our own ranks, we build close friendships that help us cope with the demanding nature of our work.

Despite the hard work, the financial stability and adventure make this job worth it. And at the end of every day, when I see a spotless cabin and a happy guest, I know I’ve done my job well.

What's life like on board for a junior officer?

I recently joined Le Lyrial as a junior officer in the ship’s operational and navigational team. The transition from cadet to officer has been both exhilarating and demanding, requiring precision, discipline, and the ability to take on greater responsibility.

Responsibilities & Workload

As a junior officer, my primary responsibility is assisting the senior bridge officers in navigation, safety oversight, and shipboard operations. I work under the direct supervision of the Second Officer and First Officer, learning the intricacies of bridge watchkeeping, voyage planning, and emergency procedures.

-

Bridge Watchkeeping: I stand watch in four-hour shifts (typically 00:00-04:00 and 12:00-16:00), assisting in monitoring the ship’s position, radar readings, and weather conditions.

-

Navigation & Chart Work: Before each voyage leg, I update electronic and paper charts, cross-checking waypoints and ensuring compliance with the passage plan.

-

Safety Inspections: Every week, I assist in lifeboat drills, fire safety checks, and equipment inspections to ensure regulatory compliance.

-

Mooring Operations: During port arrivals and departures, I am stationed at the bow or stern, handling mooring lines under the guidance of the Chief Officer.

-

Crew Management: I coordinate with deck ratings for daily maintenance tasks, including hull cleaning, painting, and securing loose equipment.

Mistakes & Accountability

Mistakes are taken very seriously aboard. Errors in navigation, safety procedures, or mooring can have severe consequences. If I make a mistake, the response depends on the severity:-

-

Minor Errors: A debrief from the senior officer, additional training, and close supervision during future tasks.

-

Moderate Errors: A formal report may be filed, and I could be assigned additional simulator training or retraining in a specific procedure.

-

Severe Errors: If the mistake risks passenger safety or vessel security, I could face disciplinary action, including suspension or dismissal. Critical errors, like mishandling navigation during my watch, are escalated to the Captain.

Daily Routine & Watchkeeping

My schedule follows a strict rotation, divided into navigational duties, maintenance oversight, and safety compliance.

00:00 – 04:00: Night Watch

-

Monitor AIS, radar, and ECDIS for vessel traffic and navigational hazards.

-

Conduct hourly log entries on ship speed, weather, and fuel consumption.

-

Maintain communication with engine room and security personnel.

04:00 – 12:00: Rest & Training

-

Sleep and recover from the night shift.

-

Participate in safety drills and officer training sessions.

12:00 – 16:00: Noon Watch

-

Assist in adjusting the course as per weather updates.

-

Oversee deck maintenance and coordinate small repairs.

16:00 – 00:00: Administrative Tasks & Port Planning

-

Review voyage plans and update navigation logs.

-

Conduct equipment inspections with senior officers.

-

Prepare for next-day operations, including briefing deck crew on mooring duties.

-

As a junior officer, I share a cabin with one other officer of the same rank. The cabin is compact but functional, equipped with bunk beds, a small desk, a wardrobe, and a private bathroom.

-

Senior officers, such as the Chief Officer and Captain, have private cabins.

-

The shared space requires maintaining a tidy and respectful environment, as rest periods are crucial given our different shift rotations.

-

The standard officer uniform includes white dress shirts, epaulets, navy trousers, black shoes, and a regulation jacket.

-

During mooring and deck work, I wear high-visibility gear, gloves, and a helmet.

-

The company provides the first set of uniforms, but I have to pay for replacements.

-

Formal uniforms for official events or dinners are also required, and officers must maintain their appearance.

Becoming a junior officer requires extensive training and certification:-

-

Maritime Academy (3-4 years): I attended a maritime academy where I earned my Officer of the Watch (OOW) certificate.

-

Sea Time as Cadet (12-18 months): Completed onboard training under senior officers, logging practical experience.

-

Examinations & Licensing: Passed written and oral exams, including STCW (Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping) modules covering firefighting, first aid, and survival techniques.

-

Company-Specific Training (1-3 months): Before joining Le Lyrial, I was recruited through a maritime agency specializing in officer placements. The company handles direct contracts for senior officers, but junior officers like myself often start via agencies. I then completed company induction training, including familiarisation with Ponant’s specific safety protocols.

-

Guest Interaction: As a junior officer, my direct interactions with passengers are limited but still occur. I may answer guest questions during embarkation or while moving through public areas. During captain’s dinners or shipboard events, officers are expected to engage with passengers in a professional and approachable manner.

-

Tips & Gratuities: Unlike hospitality crew members such as waiters and cabin stewards, junior officers do not typically receive direct passenger tips. However:

-

Some luxury cruise lines distribute a portion of service charges collected from guests among all crew, including officers, as a form of discretionary bonus.

-

Senior officers may receive direct gratuities from passengers, particularly for exceptional service or private excursion arrangements.

-

The amount varies, but gratuity pools can sometimes add an extra $200-$500 per month, depending on ship policy and passenger generosity.

-

Any tip-sharing policies are determined by the company and vary between ships and contracts.

-

-

After gaining sufficient sea time as a junior officer (typically 12-24 months), the next step is to qualify as a Second Officer.

-

This requires completing additional sea service (minimum 12 months as an Officer of the Watch) and passing the Chief Mate/Master (STCW II/2) written and oral exams.

-

Exams include advanced navigation, meteorology, cargo handling, stability, and shipboard emergency response.

-

Training also involves attending mandatory simulator courses for radar, ECDIS (Electronic Chart Display & Information System), and leadership management.

-

After 3-5 years at Second Officer rank, officers can progress to Chief Officer, followed by Captaincy with further sea time and examination.

-

Salary: As a junior officer, I earn approximately $2,500 to $4,000 per month, depending on experience and the specific contract negotiated through the agency. As an example, a 2nd Engineer at Carnival Cruise Line earns approximately €6,800 per month.

-

Bonuses: Some contracts offer performance-based bonuses or extra pay for additional duties such as safety inspections or additional certifications.

-

Accommodation & Meals: Provided by the company at no cost, meaning I have very few personal expenses while at sea.

-

Travel Benefits: Officers receive discounted or complimentary travel on company ships when on leave, as well as flights covered to and from the vessel at the start and end of contracts.

-

Medical Coverage: Comprehensive health and accident insurance is included in my contract while onboard.

-

Career Progression: After accumulating sea time and passing further exams, I can move up to Second Officer and then Chief Officer, which significantly increases salary and responsibilities.

Contract Conditions:

-

Length: Junior officers often engage in contracts ranging from 3 to 6 months, depending on the cruise line’s operational requirements and the vessel’s itinerary.

-

Renewal: Contracts may be renewable, with opportunities for junior officers to continue their tenure based on performance evaluations and available positions.

-

Time Off: After completing a contract, officers usually receive a period of leave. The length of this leave can vary but often mirrors the duration of the contract served.

-

Rotation Schedule: Many cruise lines operate on a rotation basis, allowing officers to plan their time on and off the vessel in advance.

-

Officer Mess: Unlike crew, officers dine separately and have access to a more varied selection of food, including fresh seafood, meats, and salads.

-

Breaks & Refreshments: During night shifts, coffee is a necessity. Officers are permitted to prepare light snacks in the officers’ pantry.

-

Fitness & Recreation: The ship’s gym is accessible during non-working hours, and some officers use the crew lounge to watch movies or unwind after shifts.

-

Senior Officers (Captain, Chief Officer, First Officer): Professional and structured, focusing on performance and adherence to safety regulations.

-

Deck Ratings & Crew: I interact with deckhands daily, ensuring tasks are executed safely while maintaining a level of authority.

-

Engineering Officers: Coordination is essential for ensuring smooth propulsion, power management, and emergency response.

The most challenging aspect of my role is adjusting to the intense workload and responsibility that comes with bridge watchkeeping. Navigating through unpredictable weather, responding to emergency drills, and managing fatigue are all part of the experience. However, the reward lies in the prestige and career progression. Every day brings a new learning opportunity, and the potential to advance to senior roles is highly motivating.

Although my work is demanding, the thrill of standing on the bridge during open-sea navigation, guiding the ship through narrow channels, and ensuring the safety of all aboard makes every challenge worth it.