My beloved wife Monique passed away on 23 December 2023. So I was now faced with making “our” Spring Roadtrip 2024 south to Andalusia by myself.

My second stopover was with an old acquaintance and his wife, who live south of Toulouse.

During my stay they kindly took me to see both Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges and the gallo-romaine villa of Lassalles.

This post is about our visit to the Cathedral of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges.

Where are we?

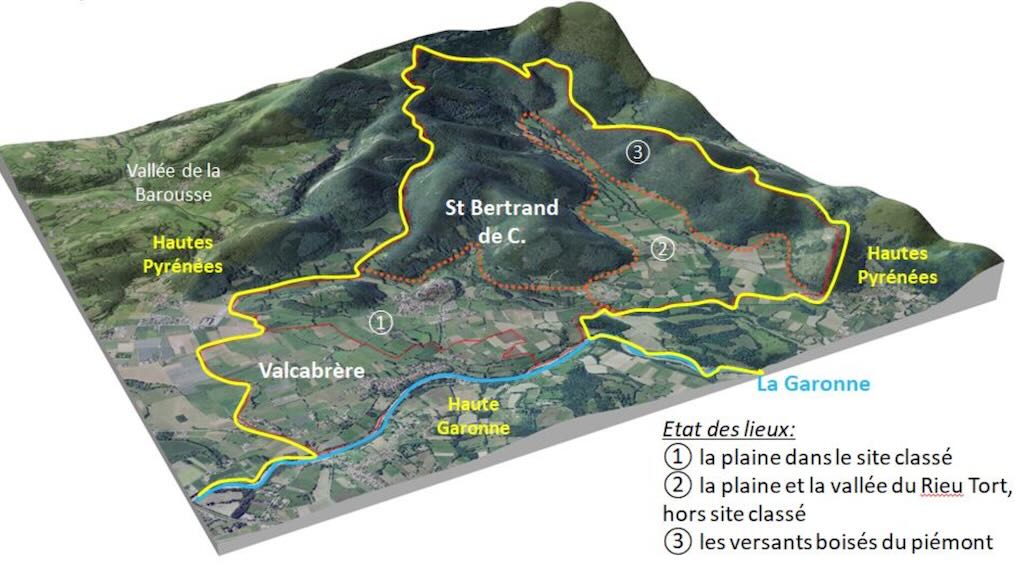

We are visiting the commune of St-Bertrand-de-Comminges, a member of the Les Plus Beaux Villages de France (“The Most Beautiful Villages of France”). As we can see the commune is very near the Garonne, which flows down from the Spanish Pyrenees to the Gironde estuary at the French port of Bordeaux (around 250 km away). It’s also worth noting that the commune is also in the Hautes-Pyrénées, which means that it’s in one of the départements of the French Pyrenees.

The area has a very prestigious historical past, and the most obvious example is the Sainte-Marie Cathedral sitting majestically on a rocky peak (515 m above sea level). A peak once cut by Quaternary glaciation (started 2.58 million years ago) and now surrounded by a so-called terminal moraine sitting above the left bank of the Garonne (which flows by at 428 m above sea level). The rock peak is surrounded by a combination of trees, pastures, and livestock, which the experts love to call “sylvo-pastoral foothills” (piémont sylvo-pastoral in French).

We will visit the cathedral, but it’s worth noting that the communes of St-Bertrand-de-Comminges and Valcabrère are also home to the remains of the Roman town of Lugdunum Convenarum. Since 1979 a total area of 539 hectares has been classified as monument historique and patrimoine national (historical monument and national heritage).

Just for clarity, the word cathedral should only appear with a capital “C” when it is used as a proper name, e.g. Sainte-Marie Cathedral.

Early history

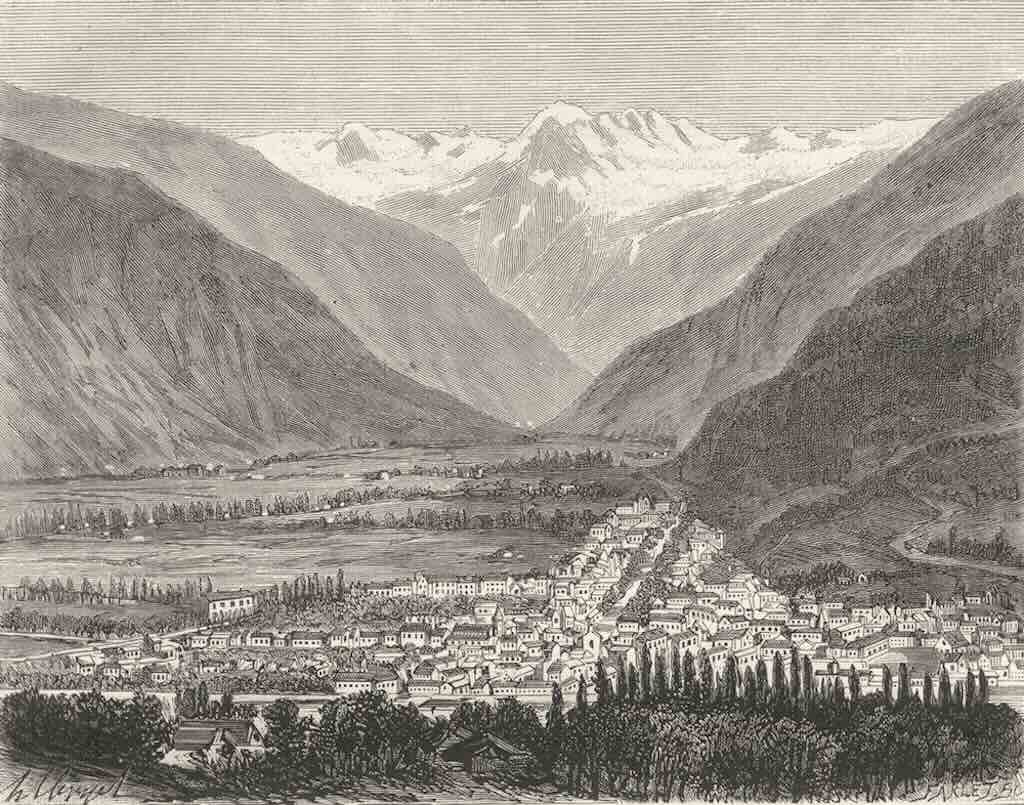

The above engraving from 1881 highlights that Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges is a small rock outcrop surrounded by peaks of the Pyrenees foothills. It also highlights the valley and plain that leads down to the Garonne.

About 8 km distant from the site of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges we find the town of Aventignan and the decorated caves of Gargas that date from the Upper Paleolithic period, or about 27,000 years ago. It’s not difficult to imagine that early man must have frequented this region, even if the known history of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges only begins in the 1st century BC.

The first human settlements were on the nearby peaks of Mont Laü and Arès. In the plain, it is supposed that there might have been a market installed on a crossroads connecting the mountain and the plain. It is this hypothesis that might have led Pompey (106-48 BC) to build in 72 BC the first town of Lugdunum on the site of that original crossroads. It’s suggested that the name is originally Celt, and meant “the hill of the god Lug” (or perhaps Lugus). It’s not clear why the Romans would have adopted this name.

Pompey moved populations from the surrounding valleys, Celtiberians, Arevaques and Garunni, and created a province. Initially it would have served as a military outpost for controlling the western border of the Roman territories and keeping open the communication route to the north of the Iberian Peninsula. The town sat at the foot of a natural oppidum, a kind of fortified settlement exploiting the natural defensive features of a rock outcrop. The crossroads linked Bagnères de Luchon (Onesiorum Thermae) to Agen (Aginnum) and Toulouse (Tolōsa) to Dax (Aquæ Tarbellicæ).

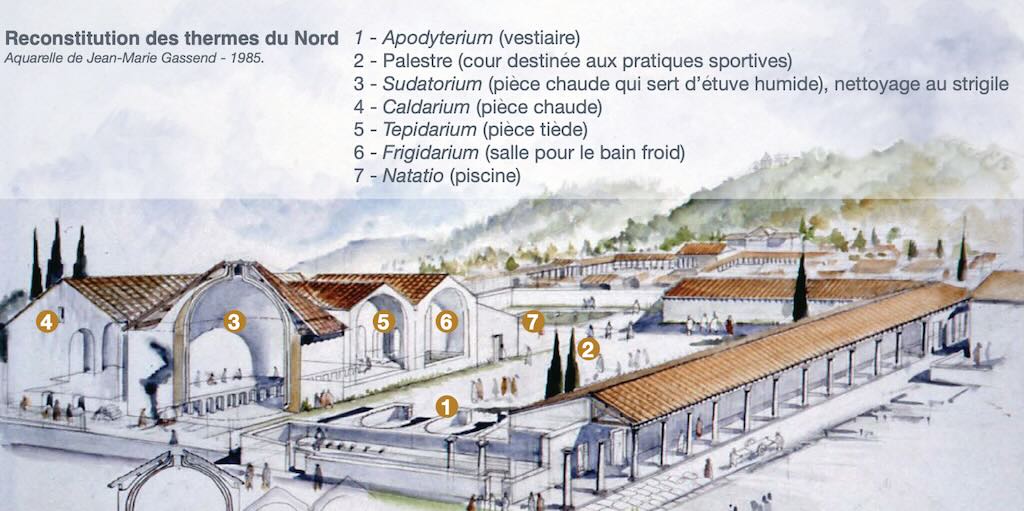

Being at the crossroads of natural land and river routes, the small town grew and in the Augustan period (27 BC to AD 14) it was named the capital city of region. This position gave it a primordial role, both political and administrative, in the ancient province of Aquitaine (Gallia Aquitania). It took two to three decades for the city to build the obligatory urban monuments, e.g. macellum, square, theatre, palaestra, balneae, etc.

Around AD 100 the expression Lugdunum Convenae appeared, where convenae probably referred to the idea of a “gathered people”.

Between the 2nd and 4th centuries, the city then expanded to cover over 36 hectares, and it acquired the title of “Roman colony”, underlining its privileged status and importance in the region. There is mention of the local population reaching around 10,000 which was very substantial at that time.

Water was carried by an aqueduct from Tibiran-Jaunac. Rich residences were established on the outskirts of the forum. Rural farms occupied the first terraces, separated from the Garonne by a honeycomb of retaining walls. On the wet meadows bordering the Garonne, a port (or a pier) had to be built in order to develop trade and facilitate the supply of construction materials. The surrounding plain hosted a military camp and a peri-urban religious district, along with a few funerary monuments.

At the end of the 4th century and the beginning of the 5th century, a period of political unrest (breakup of the Roman Empire) and economic decline, the city experienced the first abandonment of buildings on the plain, with people moving to the high ground. In 410, the city was conquered by the Visigoths, who then made Toulouse their capital. In the 5th century, the rampart of the upper town was built.

At the beginning of the 6th century the Franks replaced the Visigoths, and Lugdunum Convenae became involved in a succession dispute that ended with the sacking of the city in the year 584, with the “massacre of almost all of its inhabitants”. Very unlikely, but there was certainly a very noticeable decline in the local population, and coupled with a weak or non-existent central authority, nobles in the castles started to flex their muscles, and feudalism begins to take shape.

Throughout that “dark age” between the 7th and 10th centuries, Civitas Convenae began to give way to the “County of Comminges”. We see the appearance of the Counts of Comminges, and a bishopric was established again by Abraham, Bishop of Comminges. In the second half of the 10th century, the first Count of Comminges, Arnaud, appeared. Wikipedia has a page on the “Roman Catholic Diocese of Comminges” and mentions both Abraham and Arnaud.

As the city grew in importance, so did the stories surrounding it. Pompey is said to have founded Lugdunum Convenarum or Convenae (Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges) so that he could force together the turbulent Pyrenean tribes that he wanted to pacify. It is also said that Herod Antipas (ca. 20 BC – ca. AD 39) was himself exiled there for greed by the Emperor Caligula. And it is also said that the wife and niece of this former tetrarch of Galilee, Herodias and her daughter Salome, who contributed to the death of John the Baptist, accompanied him, giving birth to many Pyrenean legends.

Bertrand de l'Isle-Jourdain

I’ve read that a certain Bertrand de l’Isle-Jourdain became the bishop of Comminges in 1083, and undertook the construction of the first cathedral and the “religious city” at the top of the rocky peak. It was also under his authority that the construction of the Saint-Just basilica in Valcabrère began. The upper town was guarded by a faubourg, which was an agglomeration outside the city walls but formed around a throughway leading outwards from a city gate (“suburbs” were further away). Along the Garonne, the fortified town of Valcabrère replaces the port suburb of antiquity.

There was a Aton Raymond de L’ISLE-JOURDAIN (1022-1080), sometimes presented as Aton Raymond de L’ISLE, Seigneur de l‘Isle-Jourdain. He married Gervaise de Noé de MONTAUT (1025-?), and they had two sons and two daughters. The first son Raymond Bertrand de L’ISLE-JOURDAIN (1045-1123) married a different Gervaise de NOÉ (ca 1050-?). One daughter married Arnaud Pons de MONTAUT, and the other married Roger de NOÉ.

The second son was Bertrand de L’ISLE-JOURDAIN (1055-1123), and is often presented as Saint Bertrand. One of Raymonds descendants, another Bertrand de L’ISLE-JOURDAI (1227–1286), was bishop of Toulouse from 1270 until his death.

L’Isle-Jourdain is a commune in the Gers, south-western France, and is about 100 km from Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges. Montaut is a commune in the Landes, south-western France about 90 km from Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, and Noé is a commune in the Haute-Garonne, south-western France, about 80 km from Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges.

It’s interesting how the families l’Isle-Jourdain, Noé, and Montaut were intertwined together through marriages, and united lands that were spread over nearly 150 km.

It would appear that Bertrand de l’Isle was particularly active in trying to improve the living conditions of the population by developing agriculture, livestock and trade. The monks of the convent of Valcabrère and the canons of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges cultivated the land between the two sites. My understanding is that they followed the practices of the Roman engineers in controlling the alluvial flood plain along the riverside. They created narrow plots with raised paths, hedges and irrigation channels. The ancient buildings were gradually dismantled and the material reused for lime kilns and in the construction of new (medieval) buildings.

Upon his death in 1123, the tomb of Bertrand de l’Isle became a place of pilgrimage whose fame extended well beyond the borders of region. Recognised for his miracles, he was canonised in 1218 by Pope Honorius III. And in his honour, the medieval city abandoned the ancient name Lugdunum Convenarum (or Civitas Convenarum) and adopted that of its memorable bishop in 1222.

Over the centuries, veneration for Saint Bertrand and the fame of Saint Lizier encouraged a growing number of Jacobean pilgrims to take the path through the Pyrenean foothills.

After the first Romanesque church was built its worth mentioning Raymond Bertrand de Got. He was appointed Bishop of Comminges in 1295, Archbishop of Bordeaux in 1299, and elected Pope in 1305 with the name of Clement V. In 1304 he began the construction of a new Gothic-style cathedral in Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, building on top of the older church. The construction of a Gothic cathedral (1305 to 1352) reaffirmed the wealth of the bishopric, and was completed under the bishopric of Hugues de Castillon. The interior decoration was almost finished in 1535, when Bishop Jean de Mauléon renovated the choir, gave it Renaissance stalls, and also finishing the stained-glass windows.

Except for minor changes and a few decorative additions, we can today still see that original Gothic construction.

Until the 15th century, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges being both a bishopric and the capital of the county, combined religious and political powers. However, it lost its political role following its attachment to the crown of France in 1454.

But from the 17th century...

The bishops abandoned the episcopal city of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges in favour of Saint-Gaudens, which became the new seat of the seminary. A road was built (between 1764 and 1792) to connect the two towns, and Valcabrère lost its walls to allow the road to pass. The faubourg also lost its function as a town entrance. The Revolution and the Insurrection of 1792 led to the destruction of the convent.

With the disappearance of the walls, hamlets appeared forming new public spaces on the site of the old communal meadows. The old farming techniques were replaced by apple orchards and crops such as rye, vegetables, etc. The wooded hillside was cleared to make place for a vast network of meadows. Chestnut groves were planted in order to feed the farmers and also to fatten the animals (pigs, sheep). Little by little, the pastoral landscape that we see today took root.

In the 18th century, with the creation of the royal roads, wood and marble took to the road, and no longer travel by raft on the Garonne. In 1790, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges lost its role a capital of the canton, and in 1801, it lost the bishopric.

So over time the territorial importance of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges was gradually dismantled.

From the 19th century onwards, the decline accelerated, the cathedral became just another church, living on the memory of times past.

The 19th century also saw the appearance of pilgrimage routes and seaside tourism, and after World War II Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges became a city of heritage on the tourist circuits. Agriculture became mechanised, and the service sector moved to the ski resorts. Today a few hundred people live in the ancient Lugdunum Convenarum, and their only source of income is tourism.

What was a powerful and profound expression of spirituality and power, is reduced to a tourist attraction for mass consumption and trivialisation. Reality is a terrible task master.

And what of Val d'Aran?

We need to look more carefully at expressions such as Lugdunum being a “military outpost for controlling the western border of the Roman territories and keeping open the communication route to the north of the Iberian Peninsula”, “pilgrims to take the path through the Pyrenean foothills”, and “Comminges being both a bishopric and the capital of the county, combined religious and political powers”.

What this meant was that there was a “natural” route of communication across the Pyrenees between France and Spain, following the bed of the Garonne River to its source, the Pla de Beret (Beret Flat) near the Port de la Bonaigua. Today this is the French N-125 (Montréjeau to Fos and the Pont du Roi at the frontier), and the Spanish N-230 (down to the Avenida Alcalde Porqueras in Lérida 188 km away). This “natural” route is usually known as Val d’Aran.

When Lugdunum became the capital of the region, its influence would certainly have reached the Aranese lands. It is known that the bishopric of Comminges, after the year 1000, appointed the parish priests of Aran. In 1387 two of its parishes were in Val d’Aran. However justice depended on the Principality of Catalonia and the government on the Crown of Aragon. At the end of the 18th century, with the French Revolution, the bishopric of Comminges disappeared, and the already weakened ecclesial authority over Val d’Aran disappeared completely.

In addition to religious issues, Comminges and Val d’Aran were united in many other ways. There were multiple hospices in the region to facilitate pilgrimages and the crossing of the Pyrenees. Cross-border relations were fluid and economically profitable. Ordinary people in both regions traded, inter-married and owned property. Today the French often go shopping in Spain, but until recent times, it was far easier for the Spanish to come into France to trade and buy goods.

Today, in Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges

The pastoral landscape has become simplified. Forest plots divided according to inheritance are no longer known and maintained by their owners. Abandoned meadows are spontaneously reforested. The chestnut groves are still there but no longer contribute to the local economy. Some plots in the meadows are still carefully maintained, but most are inaccessible and have been abandoned.

Plot sizes have grow, and farmers now plant fodder crops (alfalfa, corn, hay) and some still cultivate the fruit trees. Grassy areas are used for livestock farming.

Now Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges and Valcabrère are just two rural villages.

However, they still have the cathedral and the basílica Saint-Just de Valcabrère. The latter was enriched, at the beginning of the 20th century, by the discovery of the remains of the ancient city of Lugdunum.

Some people might consider the region an example of a kind of neo-ruralisation, a return to old rural, almost medieval, traditions. It seems to chime with the desire for a quieter life. The region might offer a relaxed life-style for the well-healed (nice “antique” expression and very appropriate), but what’s it like to live on the minimum wage? What’s the unemployment rate? Is it easy to find a job? Do younger people stay, or move to the larger local towns and cities? Are the public services, such as doctors, hospitals, transport, schools, post, shops, etc. adequate? Where are the cultural outlets, e.g. libraries, theatre, museums, etc.?

In addition to our visit to the gallo-romaine villa of Lassalles, we also visited a small market town. I was impressed by the local market with all its stalls, plus the variety of shops, etc., but there is also the risk that one flourishing town centre creates a kind of economic and cultural deserts around it.

Archaeological research on the Lugdunum site

Since the 16th century, the Lugdunum site has had a certain fascination for the studious traveller. But the first archaeological research was only carried out in 1913, and though to 1970 the site was carefully surveyed and researched. Since then collections have been inventoried, old work verified, chronology adjusted and readjusted, and cartographic representations of the city now show its evolution and identify the newly discovered buildings. The last large-scale excavation, carried out from 1990 to 2004, uncovered, then reburied, a public building.

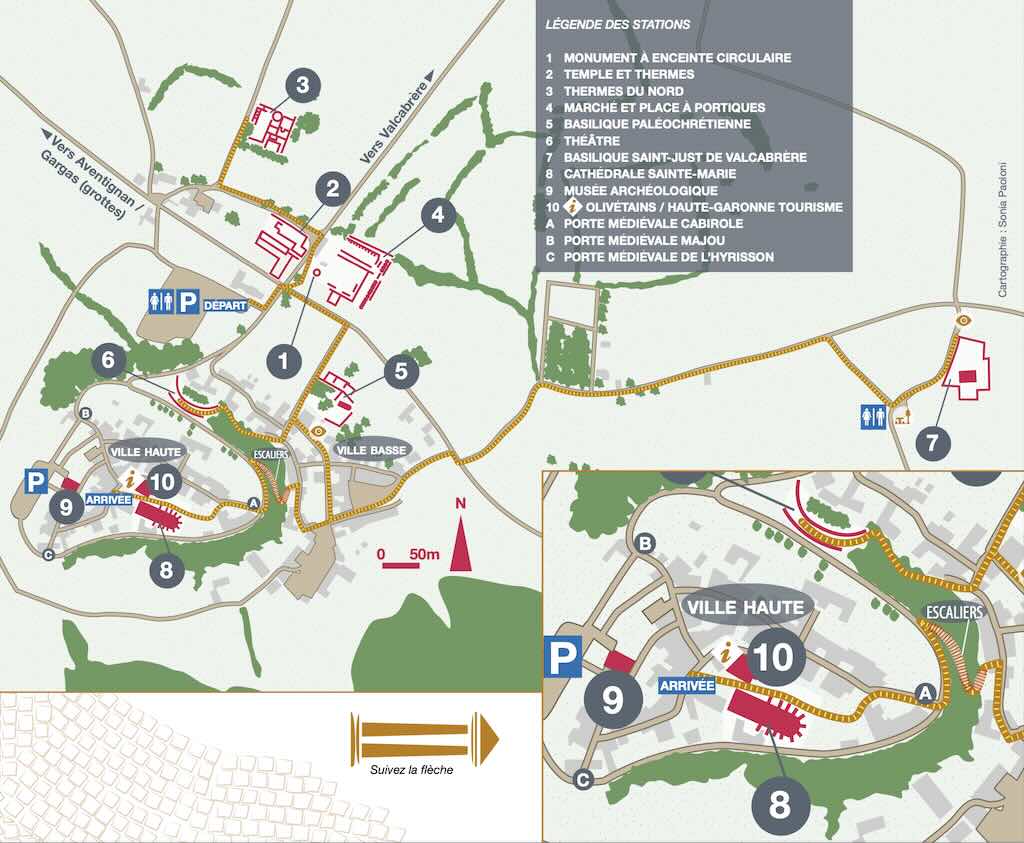

Today, the excavated and accessible monuments are located in the public sector of the ancient city. This includes the temple, the thermal baths, the forum, the early-Christian basilica, the theatre and the market. The military camp located on the outskirts of this urban area is one of the best preserved in the Roman world.

Above we can see the antique city of Lugdunum in green, with the different archaeological vestiges. The black line defines the protected heritage area (monument historique), the yellow line defines the area under permanent archaeological study (patrimoine national), and the brown patch is a tumulus.

For those who passion for the history, architecture, urban planning, etc. of the two villages I can suggest:-

- 2000 years of history

- Canónica de Saint-Bertrand de Cominges (in Spanish)

- Les secrets de Saint-Bertrand de Comminges

- Les secrets de Saint-Bertrand de Comminges : Têtes de Chapîtres

- Valeur de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine de Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges et Valcabrère by Jean Marc Rinkel

- Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges

- Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges – Coupéré, « Macellum »

- Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges – Quartier du Plan, basilique chrétienne

- Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges – La Bourdette, thermes du « forum »

- Territoires environnant la cité antique et médiévale de Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges

From Roman ruins to a medieval cathedral

Our visit was more a passing stroll than an attempt at a detailed view of a local monument. We parked, walked up a couple of narrow village streets, visited the cathedral, then the museum, drove past the archaeological remains, failed to find an open coffee shop, and left to find the gallo-romaine villa of Lassalles.

In visiting a museum, site, monument, etc. I always try to give myself an objective. I didn’t know we would visit this village or its cathedral, so I set myself one of my “traditional” objectives. Can I spot the different architectural periods?

Not particularly challenging, because I guessed it was originally a Romanesque church (11th and 12th centuries) that had been expanded and refitted as a Gothic cathedral. The trick is also to look for markers, trends, etc., that point to one or other influence, often driven by economic constraints or simply the availability of skilled craftsmen and local building materials. The most obvious change from Romanesque to Gothic architecture is probably the move away from barrel vaults, semicircular arches and thick walls reinforced with buttresses. Will we find a taller more spacious interior, ribbed vaults, pointed arches, stained-glass windows, and maybe even a rose window?

Let's visit the cathedral

We are going to have to mix up what we have read about the cathedral, with what we saw on our visit.

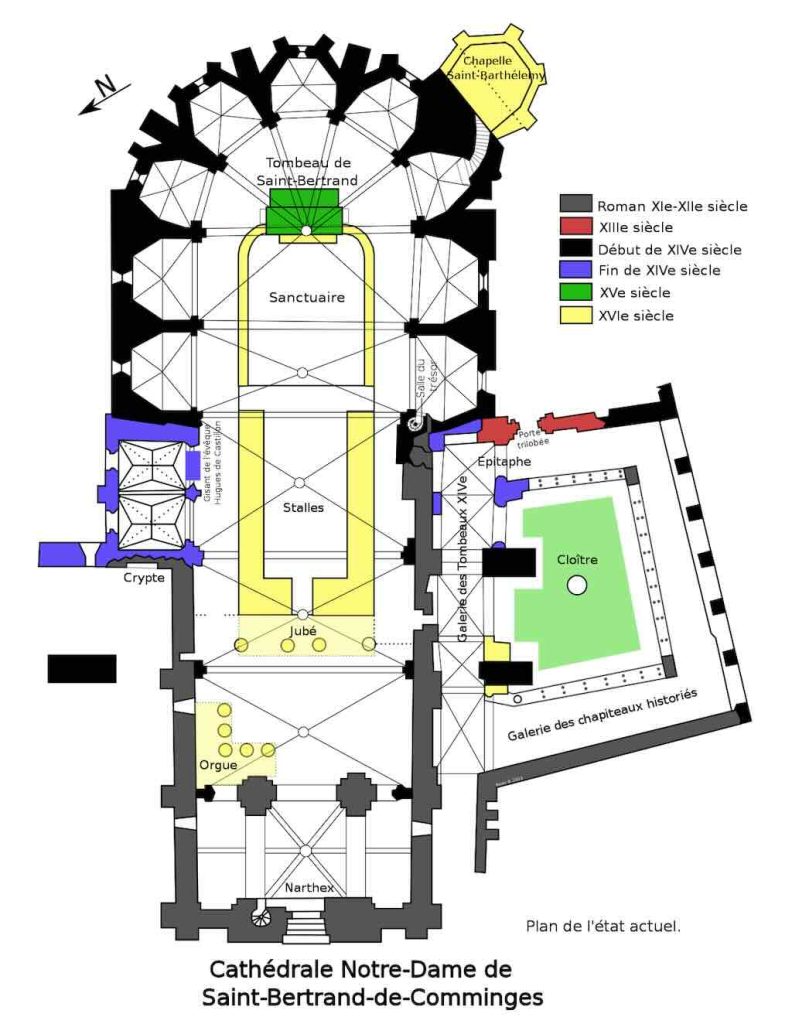

We don’t have to think, study and postulate about periods, styles, etc., the above plan tells us which are the Romanesque parts from Bertrand de l’Isle, which are the Gothic parts from Bertrand de Got, and which the Renaissance parts from Jean de Mauléon.

What we know about the original Romanesque Cathedral built by Bertrand de l’Isle at the end of the 11th century is what was preserved in the 14th century rebuild. The main entrance, the base of the side walls before the chapels, the small typically Romanesque windows, and little else. Experts think that it would have had a single nave, measured about 15 m by 35 m, with a wooden roof and the façade closed with a bell tower wall.

In the 12th century, part of the cloister was rebuilt, some capitals were kept but most were new. Also the large bell tower was constructed, however the wooden covering was added only in the 19th century. In order to build this massive looking tower a part of the narthex (an entrance or vestibule) had to be reinforced with two thick columns.

It’s not surprising that we know a lot more about the second Gothic construction (being ordered by the future Pope Clement V helps). There is a bit of a circular logic here. The need to expand the cathedral arose from the increase in the number of pilgrims. But many of those pilgrims were motivated by various indulgences for visits on designated dates. Concessions were made by Bertrand de Got (The Pope) himself. And just to make things absolutely certain, in 1309, Pope Clement V made the pilgrimage to Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges to enthrone the Saint’s relics. As you might have expected, this gave a new impetus to the pilgrims.

We know that the works began in 1304, and we are lucky to know the name of the maître d’oeuvre of this Gothic phase of construction. At least until his death in 1327, it was the canon of the cathedral called Adhémar of Saint Pastou.

In the plan of the cathedral the extent of the reform can be clearly seen. The nave is widened and nine chapels are created (five in the apse and two more on each side of the nave). A system of ribbed vaults was built sitting on pillars embedded in the new walls. Which were reinforced externally with buttresses.

The building works were continued (1336 to 1352) after the death of Adhémar by Hugo de Castillon.

The cloister

We entered the cathedral through the cloister and through a small door into the main body of the nave. The cloister is of Romanesque origin and although rebuilt many times still manages to preserves many vestiges of the period. Many of the capitals are Romanesque, but the roofing is from the 19th century.

The four galleries have different lengths, so forming a trapezoid. It was nice to see the south side open to the surrounding hills. If anything it is better preserved than much of the rest, presumably because it was a fundamental element in ecclesiastical life and the resting place for many church dignitaries.

The interior

So entering by the side door, on the left was the Romanesque part with the narthex below the tower, and on the right the Gothic nave with its ribbed vaults. The whole is about 70 m long and around 18 m wide. Cathedrals are not always large buildings and there are no prerequisites in size, height, or capacity for cathedrals. This particular cathedral is on the small size, but not excessively so. Many old cathedrals are around 80-110 m long, and 20-35 m wide.

It’s worthwhile noting that the cathedral is on an axis where the main door faces North-West and the apse points South-East. Convention has it that the apse end of cathedrals should point East, being oriented towards Jerusalem. The magnetic compass was only introduced into Europe in the late 12th century, so most cathedral builders used the North Star.

However, the reality is that cathedrals are not reliably oriented East-West, since much depends on the physical characteristics of the site, and if it was built over a previous church, or on top of a Roman or pagan temple.

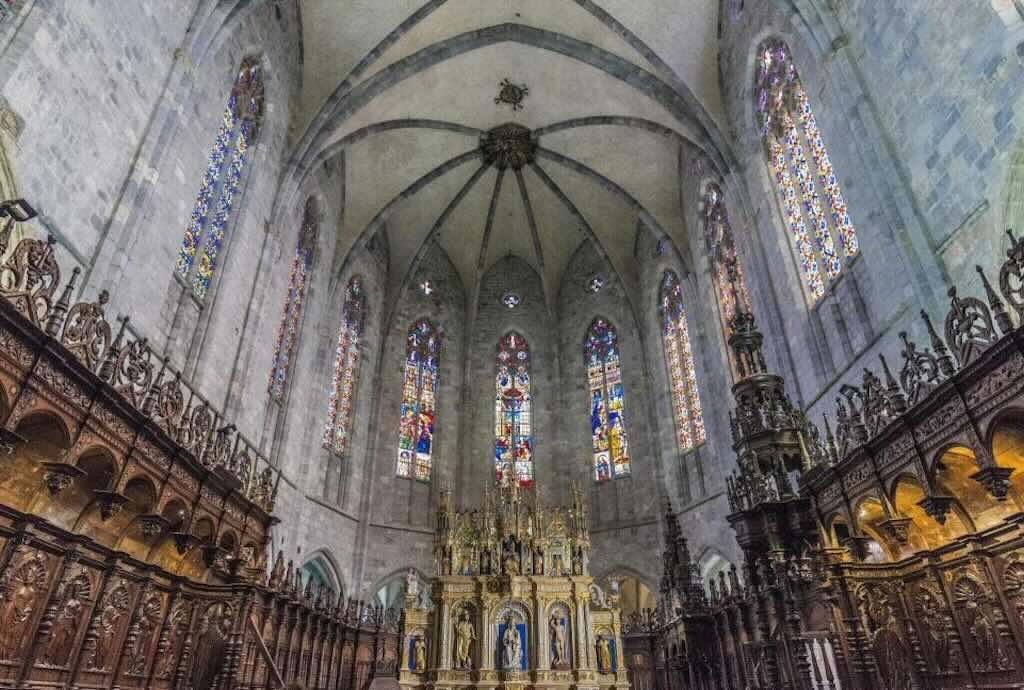

One immediate difference between the Romanesque part on the left and the Gothic part to the right was the light. A few small windows on the Romanesque part meant that the area was naturally dark, whereas the big stain-glass windows in the Gothic part let in a relative torrent of light.

This cathedral has a single nave, almost 30 meters high, covered by a system of cross vaults divided into four sections from the entrance porch, plus the large eight-ribbed vault that shelters the seven chapels in the apse. The ribs of the vaults transmit the load to the columns, which are partially embedded in the wall. The wall sections have largish stained-glass windows, indicating that they are not load-bearing. In fact if we were to look at the exterior walls we would see how the load is held and supported by heavy buttresses aligned with the columns.

Looking at these walls we can clearly see the small windows of the Romanesque period, and the large windows of the Gothic period.

In many ways the 11 Gothic chapels are not really part of the cathedral’s structural integrity, they just occupy the spaces between the buttresses.

The Renaissance interior

I must admit to not spending enough time looking at the chapels, because our attention was drawn to the Renaissance elements, the most important being the stalls in the choir. These date from the bishopric of Jean de Mauléon, at the beginning of the 16th century. What is most impressive is that they occupy almost two-thirds of the nave. Similar stalls exist elsewhere, but what is impressive here is the disproportion between the space occupied by the stalls and limited space left for pilgrims and lay people.

It’s not surprising that our attention was constantly drawn to the choir, it is striking in its size and the quality of the decoration. There are 66 choir stalls, distributed on two levels, forming a “U” in front of the altar.

The occupants, the chapter of canons, would have spent long hours inhabiting their allocated stalls. They would have become their intimate friend. They would have sat caressing the smoothly polished wood armrests, and they would have stood feeling the support of the misericords as they chanted the Divine Office.

All the surfaces are individually hand-carved. The choir is covered in characters of all kinds, both religious and purely imaginary, but more importantly each inch of that sculptured wood has a history.

I must admit I had not noticed that there was an iconographic/pedagogical program developed on the stalls in the upper gallery.

On the South side, that of the Epistle, a moral story is developed, with the fight against sin and the triumph of virtue.

The North side, that of the Gospel, is dedicated to scenes and characters related to Salvation. Above we can see Luke and Mathew in the foreground.

I’m not sure of the habits throughout Europe, but the North side is often called the Cantoris, the side of the choir occupied by the Cantor. The South side is often called the Decani, the side of the choir occupied by the Dean.

The last thing we will mention in the interior is the exceptional Renaissance organ supported on wooden pillars located right at the junction between the Romanesque part and the Gothic part of the cathedral. I’m not sure how unique this type of construction is, but I’ve never seen it before.

We must thank again Jean de Mauléon for Its initial construction. However it has been restored several times, the last being in 1974 when it was total rebuilt. But it still has more than three thousand pipes, and it is still totally mechanical.

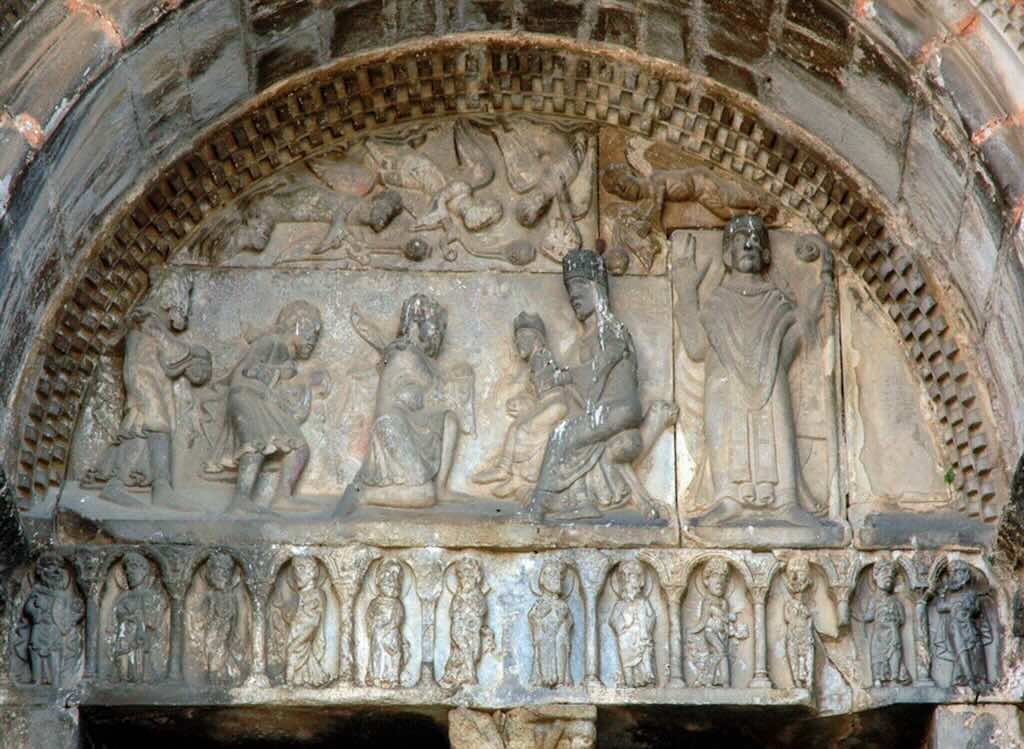

The Tympanum

Leaving the cathedral we walked past the old Romanesque tower with it main door, and I didn’t bother to look at it with any great attention. A mistake, because I later read that tympanum was particularly interesting. It’s built of four stone fragments. The central scene is an Adoration of the Magi, and from left to right the three kings are seen offering their gifts to the Virgin holding the Child in her arms. Above are five angels, and on the right, Saint-Bertrand himself (no halo so predates canonisation). The composition is Romanesque, somewhat naïve, and respecting the pedagogical desire typical of medieval iconography there are inscriptions placed above each king (not visible in the photo). They even tell us who is Maria Mater and who is Filium Dei.

What is even more interesting is that explanatory inscriptions of the royal gifts don’t mention the usual “gold, incense and myrrh”. In fact, here myrrh is miron, a Gallic form of the Latin murra or the Greek σμύρνα. Gold appears as aspron, the name of a Byzantine coin of the time, and no one knows why there is a reference to the remote Byzantine Empire in deep Gaul? Incense is not mentioned, and in its place we find “el far“, said to be a kind of cake made with the ancient cereal Triticum dicoccum.

As an aside “miron” glass is purple and made from the metal oxide manganese. Myrrh resin, coming from species of the genus Commiphora, is usually a reddish colour, but the small fruit, as it matures, turns from green to a dark reddish-purple.

According to Wikipedia aspron is a late Byzantine name for silver or silver-alloy coins. We are told that the name acquired a technical meaning in the 12th century, when the Byzantines began to refer to the billon trachy coin, which was issued in a blanched state, as an aspron. And it’s hyperpyra that is gold.

I think Triticum dicoccum is normally used for pasta or bread, and not cake. Triticum dicoccum is a type of emmer, one of the first crops domesticated in the Near East. It’s considered a type of farro food, and we should not forget that in ancient Egypt, farro held significant cultural and religious importance, and it was even used as an offering to the gods.