During my visit to Abu Dhabi in early December 2025, I visited the magnificent Sheikh Zeyed Grand Mosque.

I booked a one-week holiday package with my local carrier Luxair, and I stayed at Hotel Beach Rotana (see my review).

I also visited (and reviewed):-

My Visit

I had booked a private 1 hour private tour. This option offers a unique chance to visit the mosque outside the usual tourist routes, and can also be customised for a small family group.

There are some useful presentations about this magnificent building, namely:-

- Short introduction to Sheikh Zayed Mosque in Abu Dhabi

- The Sheikh Zeyed Grand Mosque has a visitors centre which provides guidance for both worshippers and visitors. It’s absolutely essential to read the visitors guides, in particular Mosque Manners, and the dress codes.

- Inside Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque is a great site that touches on the mosques construction, the architecture and design, lunar lighting, place of worship, and tourist attraction.

- This is why Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque was named the best landmark in the world.

- The Civic and Cultural Role of the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque looks at the mosque as a prominent architectural and intellectual landmark in UAE.

- Sheikh Zayed Great Mosque in Abu Dhabi: Islamic Architecture in the 21st Century, which also has an excellent list of further resources including two older YouTube videos about the initial construction.

Further reading:-

First Steps

The very first step was to decided which were the most important sights to see in Abu Dhabi, and the list was surprisingly long.

I finally decided on three different sites, and the first one was the Great Mosque.

The website is very complete, and I focussed on Visiting the Mosque. I read through all the background, but the two most important things was making a booking and mosque manners, and in particular the allowed (and not allowed) dress code.

On the “individual booking” it explicitly states “Secure your booking no longer than one month prior to your visit date”. However, I turned to the Private Cultural Tours, and booked a 60 minute “Private Tour” for AED 500. This option did allow me to book and pre-pay my visit outside the “one month” limit.

Second, I took very seriously the dress code requirements. For men the key criteria is to cover both elbows and knees.

The first thing to understand is that the Grand Mosque is not just a piece of cultural architecture, it is both a place of prayer that demands a sense of respect, humility, and restraint, and a national religious symbol designed to project dignity, calm, and equality.

In Islamic jurisprudence a man’s ʿawrah is traditionally defined as from the navel to the knees, and must be covered during prayer and in sacred spaces. While elbows are not technically part of the male ʿawrah, exposed elbows are associated with informality or manual labour. So the Grand Mosque applies what might be considered a local standard aimed to reduce visual disparity between visitors, and avoid clothing becoming a focal point.

The criteria for female visitors is noticeably stricter.

I had the opportunity to see these rules applied at the entry to the mosque. Some women were refused entry because they wore dresses that did not cover the ankles down to their shoes. Many women just thought a long dress was enough. One open question was with women wearing sleeveless dresses or tops, and covering the head and shoulders with a scarf. Basically the rules was that the head and shoulders had to be amply covered. And the scarf should not be, even vaguely, “see-through”. A few people tried to enter with open shoes, this was refused. Men tried to enter with short sleeve t-shirts, and this was also refused.

I was told that the worst men offenders were Americans and Australians. I had to wait for my guide for about 10 minutes, and I would guess that about 10-15% of visitors were turned away. I think in most cases they could buy something in the visitor centre shops, that would solve the problem. The most common option was to simply buy an abaya (عباية), a loose, full-length outer garment (traditionally black) worn over normal clothes.

Before leaving for my trip I ordered on-line a couple of ample white linen long-sleeve shirts and two pairs of lightweight white linen pants. I then rolled up my shirt sleeves to just below the elbow. I found them remarkable comfortable in the heat and humidity (and very easy to pack).

General Site Plan

Wikipedia tells us that the Grand Mosque was commissioned by the UAE’s Founding Father and first President, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, as a national place of worship and a symbolic statement. It was to be a mosque that would “unite the cultural diversity of the Islamic world” through architecture and craftsmanship drawn from many traditions.

To the ears of many this might sound like the usual brochure-blurb. But it’s important to realise that Islam has no single architectural canon. Early Arab mosques were simple, spread out, and not elaborately decorated, whereas Persian mosques had domes, iwans, tile-work, and an axial symmetry. Mughal and South Asian mosques were often monumental and covered in white marble and inlay, whereas the Ottoman mosques had a more vertical emphasis and central domes. Maghrebi/Andalusian mosques had courtyards, horseshoe arches, and a restrained ornamentation.

Sheikh Zayed explicitly asked that the mosque not belong to one of these traditions, but draw from several, so that no single region could claim paternity. Also we must not forget that when Sheikh Zayed initiated the project (late 1980s–1990s), the UAE was a young federation (founded 1971) without a deep, monumental Islamic architectural legacy of its own. He wanted the UAE to present itself as neutral ground within Islam. By drawing artisans, materials, and styles from many regions (Italy, India, Iran, Turkey, Morocco, China), he wanted to underline that Islam is one faith, but it should embody unity-through-diversity. He had to walk a narrow path, not replicating a single historical mosque, but not innovating radically, which might have appeared ideological. He was truly someone who saw Islam as a shared, plural, and continuous civilisation.

The mosque stands on the outskirts of Abu Dhabi on elevated land, and the choice of location was deliberate. It is near Al Maqta Bridge, associated with the first crossing between Abu Dhabi Island and the mainland, so the mosque would “announce” itself to anyone entering or leaving the city.

As we can see below the total mosque precinct covers more than 555,000 square-metres, with the building complex itself covering more than 120,000 square-metres (approximately equivalent to the size of five football fields), and making it the largest mosque in the United Arab Emirates and the eighth largest mosque in the world. The courtyard (sahn) is about 17,400 square-metres, and can accommodate more than 30,000 worshippers, which explains the large carpark spaces on both sides of the mosque.

It’s often mentioned that the mosque sits about 10 metres above street level, but this is not strictly true. As far as I know the mound on which it sits was about 10 metres above street-level, but today the mosque sits on a platform or podium (with substructure), some 15 metres above the local area.

The elevated podium houses a large air-conditioning plant, ventilation and air-handling systems, electrical infrastructure, water systems, service corridors and maintenance access, and importantly, structural foundations that isolate the mosque from heat and humidity. This allowed the mosque above to remain visually pure, with no rooftop clutter, and keeping uninterrupted marble surfaces.

We have to remember in Abu Dhabi surface temperatures can easily exceed 50°C in the shade, and un-raised floors would absorb massive radiant heat from the ground. But Abu Dhabi’s heat is also humid, typically 60–80% relative humidity (raised floors reduces condensation risk). On top of that the air is salt-laden with 5–20 g/m²/year of salt aerosols, creating marine aerosol corrosion. Finally there is the problem of dust and sand (airborne particulates), which is commonly around 150–300 µg/cubic-m, and during dust events >500–1,000 µg/cubic-m. For comparison the WHO guideline is 45 µg/cubic-m over 24 hours.

Interestingly the way the mosque is kept cool is by using nature. Firstly by lifting the floor hot ground radiation is reduced, and the underground cooling systems can operate more efficiently (and can be maintained without disturbing those above). The air conditioning is introduced just above the floor and can carry heat upwards as it warms. The mosque uses large quantities of white marble (from Macedonia, etc.), which feels cool to the touch even when the air temperature is moderate. And finally the long-term durability of marble floors and decoration is improved when it’s protected from large temperature and humidity changes.

Of course sitting 15 metres above street-level makes the mosque look like it floats calm and detached above the traffic and daily life.

As we scan through the published documentation we learn:-

- The mosque complex measures approximately 420 metre in length and 290 metre in width

- The central courtyard covers about 17,400 square metres, and mosque covers about 22,000 square metres, and accommodates around 40,000 worshipers (but can accommodate around 70,000 at a push)

- The main prayer hall is often presented as around 50 metres by 54 metres

- and finally the Masjid al-Haram (Mecca) is ≈ 356,000 square metres and can accommodate “several million”.

The figures simply don’t add up, in part because not all the figures are given. But above all because the main prayer hall is not square, but a rectangle of around 150 metres by 50 metres, and that the “mosque complex” is not what you see built above ground. I think the “complex” is the size of underground podium, and probably includes the pools, etc. My best estimate for the mosque building itself is 210 metres long and around 185 metres wide, with the open courtyard around 115 metres long and 150 metres wide.

Early planning goes back to the late 1980s, but construction began on 5 November 1996. The mosque opened to the public after Eid Al-Adha prayers and was inaugurated in December 2007. The build took about 11 years, and involved ~3,000 workers. I think the main contractor was Italian and there were 38 other different sub-contractors. The total cost was about AED 2 billion (roughly $US 545 million in 2007).

The project’s design is attributed to the Syrian architect Yusef (Yousef) Abdelke/Abdelki, along with other designers and specialists involved over the 11 years.

The mosque courtyard (sahn) can comfortable accommodate more than 30,000 worshippers, but the largest congregation so far is 70,680 worshippers on the 27th night of Ramadan 1445H (April 5, 2024), within a total attendance that night of 87,186.

The below photo allows me to mention that the mosque has a lunar-inspired lighting system. This is a system of 22 `totems´, i.e. glass reinforced concrete and steel towers, that project on to mosque the phases of the moon across the Islamic month. What this means is that the mosque’s exterior lighting changes subtly every night, with a colour palette that shifts from cool white (full moon) to deep bluish-grey (new moon). As the lunar month progresses, the light appears to “withdraw” into shadow, echoing the waning moon. So the mosque itself becomes a calendar, marking sacred time without words or clocks.

The Visitor Centre

The visitor centre is in the form of two domes, each surrounded by water. In the above photo the left-hand glass dome is the main public visitor entrance. This is where most visitors enter, and go down into the underground visitor centre.

In the entrance dome there is a lift and escalators to a lower shopping mall. I must admit I was shocked.

The underground visitor area is called Souq Al Jami’, in part a kind of curated souq, with shops selling Islamic art objects and books, calligraphy, prayer beads, perfumes (Oud, bakhoor), traditional clothes, and high-quality souvenirs.

And in part a food hall, including McDonald’s, Starbucks, Costa Coffee, etc. and even a full supermarket Carrefour.

I accept that there were no luxury fashion brands, electronics megastores, and no aggressive mall-style branding above ground, but I was still shocked.

My Visit

As instructed I presented myself at the Visitor’s Happiness Desk, and after confirming my booking, they told me to go the security gate and ask there. This just meant walking along the main mall passage to the other dome (used for VIPs, groups, staff, etc.). There the security phoned for my guide.

She was a medium height woman, probably in her 30’s, wearing a discrete light-brown-sandy coloured abaya and a colour-coordinated shayla (headscarf covering the hair). The mosque follows Sunni norms where face covering is not required (Sunni countries include Saudi Arabia, UAE, Jordan, etc.).

I had booked a private tour and we had the privilege of a buggy to take us along the underground corridor. And up to the mosque itself.

Firstly we need to understand what we are seeing. The underground tunnel brings everyone up to the left part of the gate in the foreground. Visitors are guided along the left arcade (riwaq). In the corner there is a discreet access down to the basement (ablution, services), and back up. Then they follow the arcade towards the main prayer hall (direction to south entrance D), they can drift into the courtyard (F), but are usually husbanded along to main halls. They will leave their shoes and go along the side of the open prayer hall (B), toward the main prayer hall (A). From there they return to collect their shoes, and return to the front of the mosque passing outside (through D), and walk along the “reflective” pools. (E) is a VIP area.

In the above photo we can also see the many tall poles around the parameter that provide the lunar-inspired lighting mention before. It’s also worth mentioning that inside, light sources were integrated into caves, ledges, niches and behind the carved wooden latticework known as mashrabiya. The lighting tries to emphasise the different materials used, e.g. marble panels, glass mosaics, carved plaster panels and calligraphy.

My Private Visit

Having booked a separate private 60 minute visit, my route through the mosque was quite different.

It’s worth mentioning that the average footfall through the mosque is well over 10,000 daily, and can approach 15,000 people, with peaks far higher on Fridays, Ramadan, and holidays. My guess is that a simple visitor will spend around 15-20 minutes in the mosque itself, and groups perhaps around 25-30 minutes, yet on my private visit I saw very few people. For example, i could visit the entire main prayer hall, whereas the visitor route only allowed limited entry to the south side of the main hall.

Instead of turning to the left and following the simple visitors route, we turned to the right. This was partially closed, and usually only provided access to the stairs leading to the basement (ablution, services) reserved for women. They would then normally have to cross the courtyard to the open prayer hall on the far side, reserved for women.

Firstly, as far as I know, there is no obligatory difference between the prayer of a man or woman. Technically men and women do not mix during prayers, but they may on occasion be in the same prayer hall. In congregational prayer, men and women pray in separate rows, men in front, women behind. Complete mixing (interspersed men and women) is not the norm and is generally avoided.

During major prayers such as Friday (Jumuʿah), Eid (Eid al-Fiṭr, Eid al-Aḍḥā), state occasions), women are allowed into the main prayer hall.

During daily prayers (five daily ṣalāh) men and women are in separate halls.

Our visit started with my guide insisting of taking a photo of me (with my iPhone).

We can see the entrance to the main prayer hall, with the two small open prayer halls on either side, and of course two of the four minarets (each 106 metres tall). We can also see some of the 82 domes.

Originally, minarets served one practical purpose, namely to allow the call to prayer (adhān) to be heard over a settlement. The muezzin would climb the minaret and call out from height. Today the adhān is broadcast by loudspeakers, so minarets are only symbolic.

Historically, 4 or more minarets were found on imperial or state mosques. However, there is nothing symbolic in their location, height, etc., and they are not open to the public (despite having a lift inside). I think one is home to the mosque offices, and another to the mosque library.

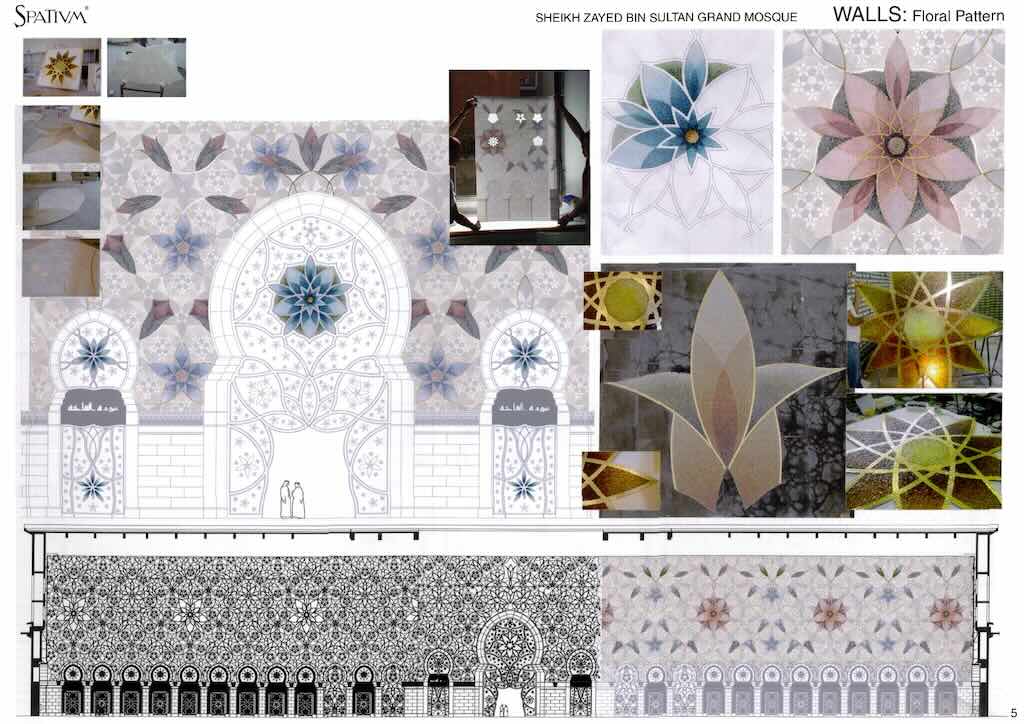

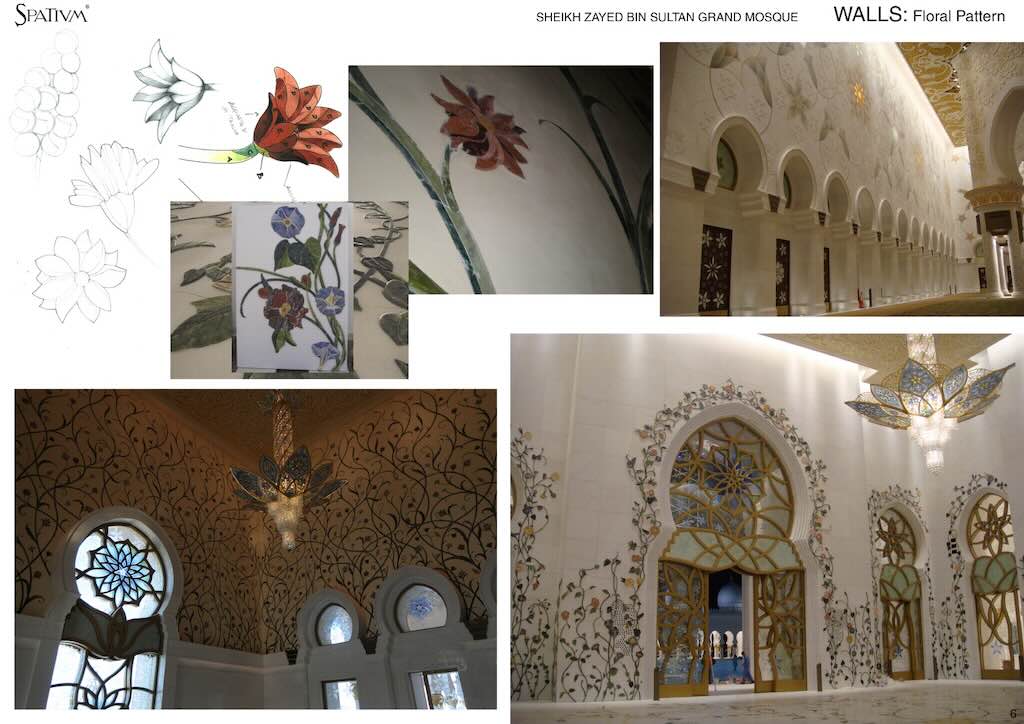

The floral decoration in pietra dura inlayed in marble is unique in the courtyard, and is the largest single floral marble mosaic in the world. There is an abundance of flowers as flush, permanent, structural decoration, across all the columns and walls.

It was Kevin Dean, a British artist and designer, who was responsible for the overall floral design concept throughout the mosque, and its translation into large-scale stone inlay. The craftsmen were largely from Italy and India, and the stones sources from all over the world.

It is true that Islamic sacred architecture traditionally avoids figurative imagery, however vegetal and floral forms are permitted and evoke Paradise (Jannah) as described in the Qurʾān.

The plants and flowers are not botanical illustrations of identifiable species. They are stylised, composite forms, said to have been inspired by flowers found across the Islamic world, e.g. lilies, tulips, irises, lotuses and roses.

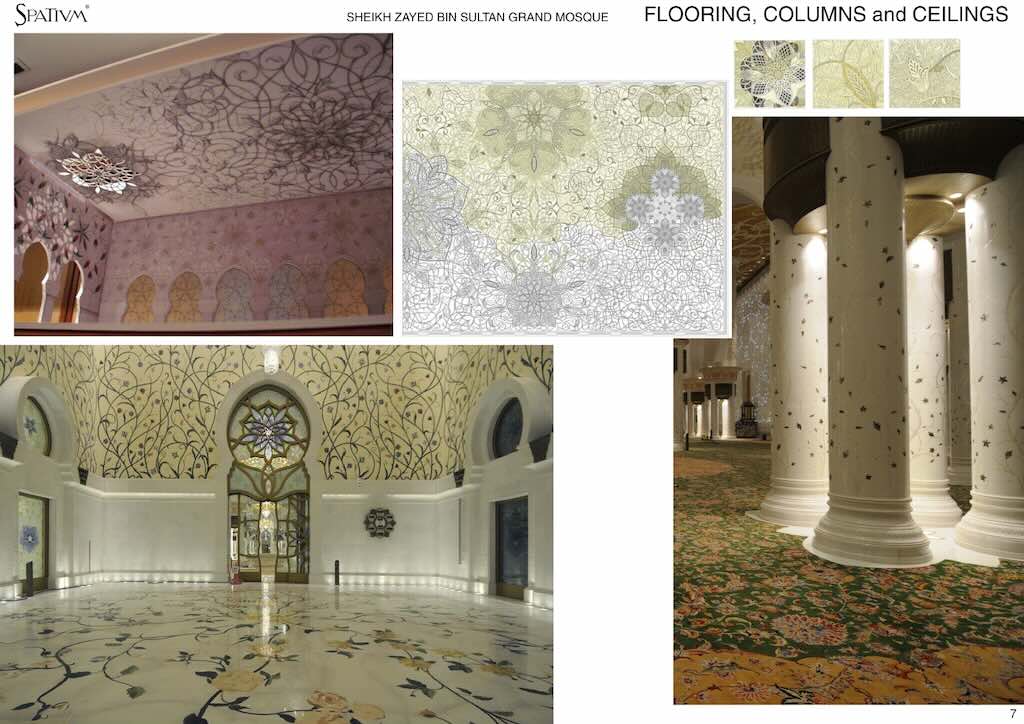

The interior design of the mosque was by the Italian company Spatium in Milan. There is some confusion because they often use “V” in place of “U”, which collides with other companies that use the name Spativm.

They are a company that works across fashion architecture (e.g. Versace), hotels (e.g. Grand-Hotel Cristallo in Cortina d’Ampezzo), private residences, and sacred architecture.

I’ve included four “mood” boards to give a flavour of what we will visit inside the mosque.

Before moving on, here are some of the more important “mega” facts publicly available on the building:-

- ≈ 504,000 tonnes of concrete

- Concrete used for reinforced concrete shell ~210,000 cubic-metres

- Steel reinforcement (rebar) ~33,000 tonnes

- more than 165,000 square-metres of SIVEC marble (dolomitic marble from North Macedonia)

- 30+ types of marble sourced internationally

- time to complete the decoration ~5–6 years

The Visit Continues

We continued on our way towards the north entrance, passing by some of the 1,096 columns in the arcades, but not forgetting the additional 96 columns that support the three main domes.

Hanging over the north gate (and south gate) we find a chandelier with a classical Islamic lantern form. It’s visually present but not as dominant as those in the main prayer hall.

The Main Prayer Hall

Passing through the north entrance, we walked into the main prayer hall, which is actually a large rectangular space dived into three longitudinal zones. The “side aisles” should not be considered as such, they are fully part of the main prayer hall, not annexes.

There is the larger central zone, and two slightly smaller side zones. Each has a domed roof, the central dome is the largest, 85 metres high outside, 70 metres high inside, and with a shell height of 32 metres. The large domes were made from pre-cast concrete sections, whereas the many smaller domes are made of fibreglass.

In the above photo we are looking through the north zone, towards the larger central zone, and beyond we can see the south zone, each with a hanging chandelier from the three domed roofs. In the below photo we are looking at the central area of the main prayer hall, looking towards the north entrance.

In fact, as we walked into the prayer hall, the first thing I saw was the carpet, which in some reports is called Qasr al-Alam (The Palace of the World).

The carpet in the main hall, with 5,627 square-metres, is the world’s largest carpet (it’s actually in several parts stitched together). It weighs 47 tons and has an estimated 2,268,000,000 hand-knots. The 35 tons of natural wool came mainly from New Zealand and Iran (plus 12 tons of cotton warp and weft). It took the Iranian artist Ali Khaliqi eight months to design it, and it uses 20 different natural dyes. It was woven by 1,200 women, aged between 15 and 60, over 16 months, working in three villages in northeastern Iran (near the town of Neishabbor in Khorasan province). One report mentions that “They were supervised by 50 men acting as technical experts”. The contract was worth $5.8 million, with $2.3 million going to the villages. Another report estimated its value at $8.5 million.

Apparently it was rolled out for the first time in Tehran’s vast open air prayer ground, the Mosalla, where photographers had to board helicopters for a full view and onlookers appeared as matchsticks on the immensity of the carpet.

Several trucks were needed to take the carpet for the showing in Tehran, and it went to the United Arab Emirates by air in two separate planeloads.

Search will turn up other carpets making the same claim, but the Guinness Book of Records states (as of Dec. 2025) “The largest hand-woven carpet measures 5,630 m² and was manufactured by the Iran Carpet Company (Iran). The carpet was created in 9 parts and assembled in the mosque. The carpet would have been around 6,000 square metres originally, but parts of it had to be taken away in order to fit it onto the floor in the mosque.“

The non-figurative vegetal motif places it firmly in the Persian garden–carpet tradition (not a prayer rug). There are variations across the carpet, with larger motifs below the chandeliers, and smaller, tighter floral units, with more overlapping stems and leaves, in the central area.

The motifs are not botanical illustrations, but its possible to recognise lotus-like bases, tulip and iris-like verticals, and rose-like rosettes.

The next thing you see is the chandelier, or more precisely all three.

These are the three largest of seven chandeliers made by the German company Faustig of Munich.

It’s interesting that superficially there appears to be two Faustig’s (one German and one Italian), both claiming to have made the chandeliers, and both are correct. It is true that the official documentation of the mosque mentions the German company, founded in 1960 by Kurt Faustig, but the production unit, also founded in 1960, is near Bolzano, Italy.

Their form is inspired by an upturned palm tree, a symbol of sustenance, prosperity, and generosity in UAE culture. The chandeliers are made of stainless steel, brass, and panels gilded with 24-carat gold. They incorporate millions of custom-developed Swarovski crystals with tens of millions of coloured crystal elements (green, red, yellow), creating spectacular refracted light (e.g. one report mention 350,000 Swarovski crystals on one chandelier). The lighting comes from 1,000’s of LEDs.

The central (largest) chandelier is 10 metres in diameter, 15 metres tall, weights around 12 tonnes, and is home to ~15,500 LEDs. They are equipped with integrated motorised hoisting systems allows them to be lowered vertically for cleaning. This occurs 1-2 times yearly, but they also have a soft air-flow system for light cleaning in-situ.

In fact the original installation used halogen lamps. These were replaced with LEDs, and a number of crystals had been heat damaged, and also had to be replaced.

The chandeliers are meant to be viewed from a distance, and as architectural features of the prayer hall, in addition to providing essential light (not many windows). But closeup they are pure engineering (in this sense they have been compared to the Eiffel Tower, elegant from a distance, and heavily engineered up close).

Before we move on the qibla wall, it interesting to look at the two opposite walls in main prayer hall.

What we see are large floral arabesque designs and vine-like geometric motifs, symbolise the paradise gardens (Jannah). The flowers of the Middle East (e.g. tulips, lilies, irises), are often seen as representing infinite growth and divine unity. The patterns combine geometry (circles, star rosettes, looping vine paths) with natural forms (abstracted flowers/leaves), blending strict mathematical order with organic life. These motifs are created as intricate inlays of semi-precious stones and marbles set into the white marble surfaces.

Some floral patterns and calligraphic panels use backlighting or fiber-optic systems hidden behind the marble to provide a soft, ethereal glow, especially around key religious inscriptions and mihrab areas.

It’s worth noting that the right-hand image is the wall which is home to the qibla, the direction of prayer for the salah, and the recommended direction to make du’a (supplications). It is for this reason that the colours are subdued.

The Qibla Wall

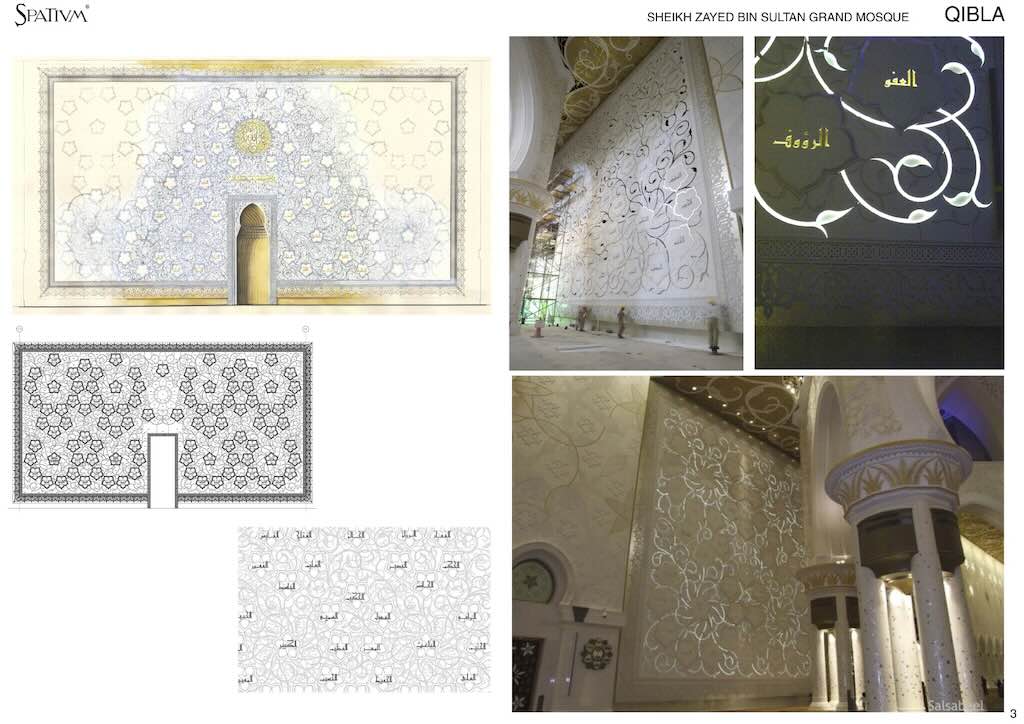

Certainly the most important feature of the mosque is the Qibla Wall, which list the Attributes of God scripted in Kufic calligraphy.

The wall uses integrated fibre-optic and concealed lighting to light-up the calligraphy. This lighting is not surface-mounted fixtures, but built into the ornamental marble and calligraphy so that the inscriptions and forms are gently illuminated. This make surfaces appear luminous and sculptural rather than flatly lit.

While daylight enters through windows in side niches, it was important to integrated artificial LEDs extensively so that interior illumination is consistent day and night. It was important that the calligraphy is visually legible and gently glowing, without spotlight glare.

So the prayer wall pointing to Mecca is treated as a “unique piece of art” integrating light with material.

Leaving

My visit ended with the Mausoleum for Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, the founding father of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The mausoleum itself is simple and sober in design, and does not feature the ornate decorative style of the mosque’s interior. At the tomb there is a continuous recitation of the Qur’an. This is a formal Qur’anic recitation, typically performed by appointed reciters in rotating shifts.

With my guide, we had a buggy takes us round the back of the mosque, to the visitor centre.