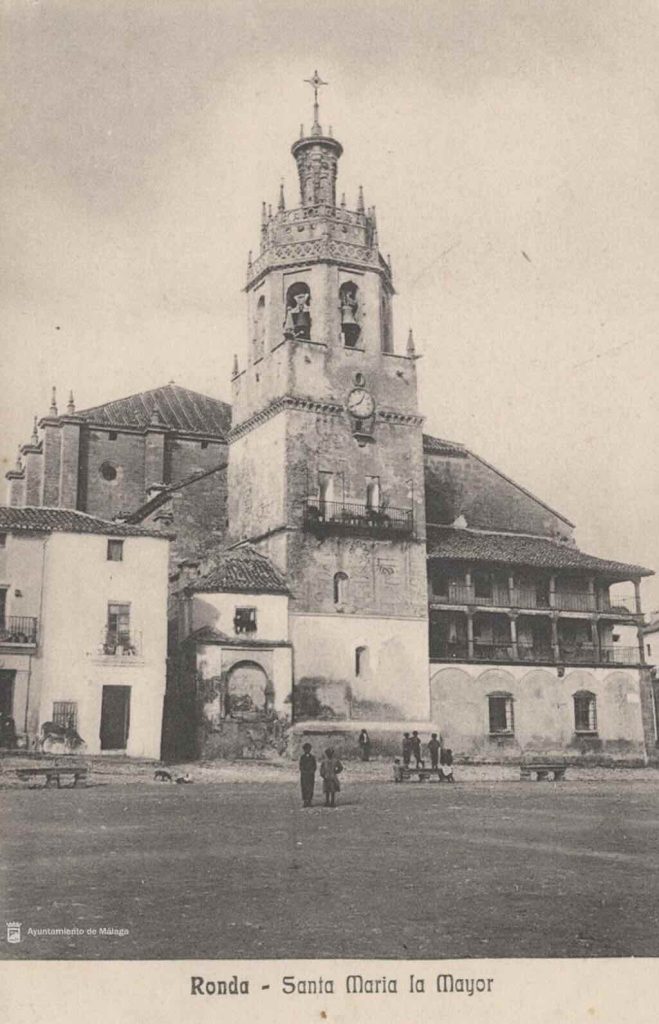

The Iglesia de Santa María la Mayor (Church of Santa María la Mayor) in Ronda, was elevated to the status of a chapter parish (parroquia capitular) by King Ferdinand the Catholic (1452-1516). It stands on the site of the city’s former main mosque, a 13th-century work of which remains of the mihrab are still preserved (see below). There is a suggestion that the mosque was erected, in turn, on the ruins of a Roman temple dedicated to Julius Caesar.

In the historical development of the city of Ronda, this was a privileged space located at the highest part of the plateau on which the original core of the city was located. And it was later protected by the city’s medieval defensive system. Archaeologists have confirmed the existence of an early Christian-Visigothic basilica with its necropolis, dating from the 6th and 7th centuries AD. This was immediately adjacent to the later main mosque and Christian temple. The building of a main mosque dates back to the 13th century, although other smaller mosques are known to have existed scattered throughout the city.

The superposition of a new Catholic church on an older mosque clearly was of a triumphalist character. It highlighted the moral, political, emblematic, and religious victory of Christian premises over everything considered impure and imperfect.

I could not find any specific royal charters or decrees granting Ronda city status, but historical records indicate that Ronda has been acknowledged as a city since at least the time of the Catholic Monarchs in the late 15th century.

During the summer Reconquista campaigns of 1484-5 Setenil, Cártama and Coín would fall (they were part of the Guadalhorce river valley). Ronda, despite being geographically isolated and with its defensive walls, would fall at the end of May 1485, and immediately afterward, the entire mountain range would surrender. The Muslim population would soon acquire the status of Mudejars under the clauses of the capitulation treaties. Underlying all these legal regulations was the royal decision to keep these Mudejars only in rural areas and replace them in the cities with contingents of Christian settlers.

The Catholic Monarchs wasted no time, and on July 15, 1485, Pope Innocent VIII promulgated a bull granting the new church in Ronda the status of abbey, with authority and jurisdiction over the towns in the region.

Juan Bermúdez de Castro, a cleric of the diocese of Seville, was the first dean. In 1505 the number of “beneficiados” was considerably increased to fifteen, with a specific “renta decimal” for each one.

We will stop a moment to understand better the concepts of “beneficiados” and “renta decimal“. The true historical sense of the Spanish term beneficiados in the context of a church or abbey refers to clerics (usually priests) who held a “beneficio“, or an ecclesiastical position endowed with income, rights, and duties, typically tied to the spiritual care of a parish or a function within a cathedral or collegiate church. It was a permanent ecclesiastical post that provided a source of income, often from tithes, rents, or land endowments. But was not just a salary, because it was an office with spiritual and sometimes judicial responsibilities. A “beneficiado“ held rights, such as a stall in the choir, a vote in the chapter, and income. And he had duties, which could include celebrating mass, preaching, administering sacraments, or overseeing aspects of ecclesiastical governance. In cathedrals and collegiate churches the beneficiados often formed the lower chapter, beneath canons (canónigos). Depending on their precise rank, function, and the local custom, they could be called “racioneros“, “capellanes“, or “prebendados“. In rural parishes, the beneficiado was often the primary priest, especially if the parish lacked a full-time rector.

In historical Spanish ecclesiastical and fiscal contexts, una “renta decimal” was a tithe-based income, usually a regular tenth part (décima) of agricultural produce or earnings, allocated as revenue (renta) to a church, abbey, cleric, or lay holder of rights to tithes. Under canon law and royal decrees in Spain, tithes were traditionally owed to the Church by landholders and peasants. These tithes (diezmos) were often divided among parish clergy, Cathedral chapters, monasteries, and sometimes the Crown (especially after the Crown obtained el derecho de presentación or appropriated tithes through amortización or military orders). Not all tithes were paid in kind, some were commuted into monetary rents, especially in later centuries. Ecclesiastical benefices might be described as having “renta decimal”, meaning that their endowment or income source came from rights to tithes.

For example, by 1798, the chapter of Santa María la Mayor had nineteen beneficiados. They constantly, punctually and continuously, sung the hours in the morning, and performed a mass for the people. In the afternoon, vespers and compline were followed by Maytines (night or before dawn office of prayer with short sung responses) and Lauds (morning prayer offered at dawn).

In 1488 the Catholic Monarchs commissioned a certain Juan Alonso Serrano to divide the town into six districts. He was alderman of the city, and through 1491 he continue the reforms in Málaga, Marbella, Vélez-Málaga, Casares, Gauzín, etc. This was done to determine which streets and neighbourhoods were in the city and who lived there, and distribute and delimit the districts. The message was clear, as seen in the names of the six districts, Saint Mary of the Incarnation (Santa María de la Encarnación), Saint Spiritus (Santi Espiritus), Saint James (Santiago), Saint John the Baptist (Sant Juan Bautista), Saint John the Evangelist (Sant Juan Evangelista), and Saint Stephen/Saint Sebastian (Sant Stevan/Sant Seuastian).

Then came the royal order to erect within each neighbourhood a Christian temple, including one dedicated to Saint Mary of the Incarnation. Not only was it intended to supplant the old main mosque, but it also received twenty “caballerías” of land, far above the ten allocated to the other parishes.

A “caballerías” of land was a historical unit of land measurement used in Spain and its American colonies, originally tied to the amount of land granted to a knight (“caballero”) as a reward for military service. Although it represented land sufficient to support a mounted soldier, its precise size varied by region and over time. During the Reconquista, land taken from Muslim rulers was often distributed in caballerías to knights who served the Crown. It was often subdivided into fanegas (not the unit of volume) or solar plots, depending on use (agriculture, pasture, or urban).

A caballería was not only a measurement but a legal concept, often tied to land titles, tax obligations, or service duties. It could be granted to settlers, soldiers, or officials as “mercedes de tierra” (royal land grants), forming the basis of rural estates, cattle ranches, or plantations. The “hacienda” system in many parts of Latin America was often built on caballería-based grants. The problem is that in Ronda, and similar Andalusian towns and cities, land was granted to settlers and soldiers as part of the Repoblación process. They were sometimes expressed in caballerías, but the size varied depending on the terrain and local agrarian practices (as well as on customary law, soil fertility, water access, and military status, etc.). It’s most likely that a caballería was a few 1,000s of square metres.

The first evidence of the construction work dates from 1508, but dated 1500 there is a mention of a temple where one of three annual festivals was held. In 1501 there was also a mention that bells were needed to call the faithful to prayer. This led to the request to the monarchs to cover the costs of their purchase. What is certain is that by 1508, there was a modest Christian temple, clearly unfinished. However, it was already insufficient to accommodate the devotees of Christian Ronda, given that the city experienced considerable population growth at the beginning of the 16th century.

Planning an expansion of the temple was possible, but the church’s resources were limited. The building costs were considerably more than the income provided by the church’s rents. On top of that no work had started on the other churches planned for the town. Even so, and with a loan from the local hospital, things did improve, and by 1534, the condition of the church already seemed solid and stable.

For much of the 17th century, the damage suffered by buildings in Ronda was superficial, but on other occasions, the consequences of storms or earthquakes, not to mention the effects of epidemics, constituted the greatest problem. These problems could not be adequately addressed because the population started to decline. In fact records show that the Mudejar tower that formed the bell tower was struck by lightening in 1523 and later in 1605. Torrential rains and an earthquake shook the foundations of the church in 1680. This required a complete reconstruction which dragged on until the second half of the 18th century.

It was Charles V who complied with the papal bull of Leo X of January 28, 1520, and granted the church in Ronda the privilege of being a “Iglesia Mayor ad instar Catedralis hispalensis“, with the obligation to observe all canonical hours of day and night. This was later confirmed in 1545 by Philip II. What this meant was that the Ronda church was a principal or “major” church in a city, and “ad instar Catedralis Hispalensis” actually meant “in the manner of the Cathedral of Seville”. The meant that it was not an episcopal see, but could function with the prestige, ceremonial dignity, and administrative structure similar to that of the Cathedral of Seville.

In the concordat signed in 1851 between Pius IX and Queen Isabella I, the canonical reduction of the church to the status of a suppressed Collegiate Church or Major Church was agreed upon, which it retains today. That meant that the church remained active as a parish church, but no longer had a chapter.

The 18th century

Ronda was one of the most important cities in the province of Málaga, but it remained an isolated mountainous location. However, as in many other Spanish cities, the 18th century was a great time for Ronda, reflected, above all, in the significant building activity during those years. In this context, the renovations carried out on Santa María de la Encarnación must be included.

By 1680, the church was severely damaged as a result of the earthquake that devastated the town, and from that date on, its reconstruction and expansion were planned, lasting until the end of the 18th century.

Today we see the blending of different construction styles, from late Gothic, through to Baroque when the new church was built.

Below I have included one of the most compact description I have ever read on the interior of a church. It described Santa María de la Encarnación in Ronda, and its almost totally incompressible. A true work of art!

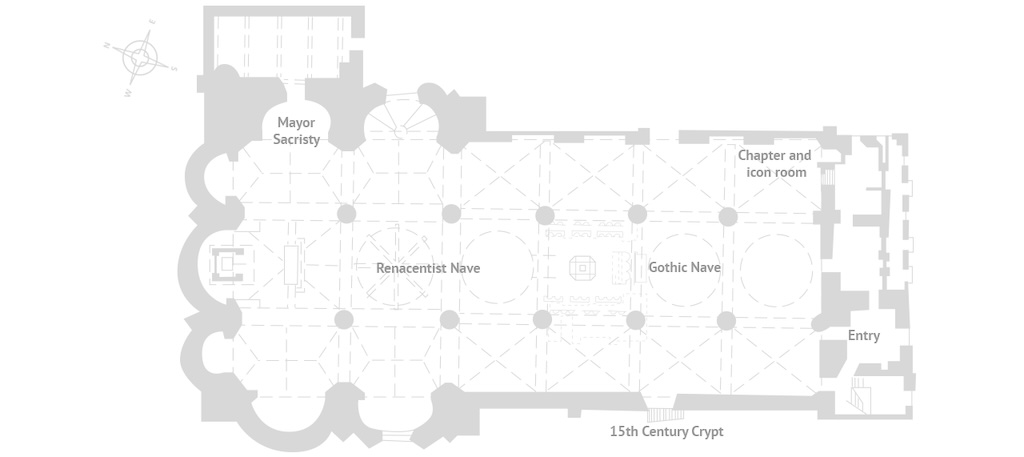

The first period includes the three naves into which the church is divided, separated by pointed arches on pillars covered with baquetones and continuous capitals decorated with cardina. Added to this is the transept and the chancel, which display a Mannerist style, more grandiose than the main body of the church, reminiscent of Málaga Cathedral. The Gothic pillars are connected by adding fluted columns with high bases that support a triumphal arch. Above this, and to give greater height to the new space, the columns project upwards, topped with Corinthian capitals supported by a large entablature. The chancel is also divided into three chapels ending in an exedra shape, the central one being the most substantial. The Baroque renovations can be seen in the plasterwork decoration that adorns the vaults of the three naves. This decoration forms quadrangular sections with hemispherical vaults on pendentives in the central nave and groin vaults in the lateral ones.

We will try to elucidate what this describes by outlining how the work on the church actually evolved (helped with a few photos).

In 17th-century Spain, “master”, when used in titles like “maestro carpintero” (master carpenter) or “maestro cantero” (master stonemason), had a specific and formal meaning within the guild system. They were craftsmen who had completed formal training and demonstrated a recognised level of technical skill, knowledge, and experience.

In the last decade of the 17th century, work began on the church’s roof, and work continued into the following century. In the early 18th century, the Granada-born master Francisco Gutiérrez Sanguino, who had also been commissioned to lay the church’s flooring, was working on the main chapel. Soon after, the chapels started leaking rainwater, so in 1710, Sanguino himself brought in the architect Laureano Iglesias from Seville, who, together with a master builder from the city, attempted to correct the defect, paid for by Master Sanguino. Later it was reported that the problem was resolved, with Sanguino himself paying the Sevillian master the sum of 7,000 reales. However, the roof continued to leak.

In fact, the ecclesiastical and secular councils of the city of Ronda filed a lawsuit against Francisco Gutiérrez Sanguino, master carpenter, his wife, who had acted as guarantor, and Francisco del Castillo, master stonemason. They had agreed to carry out the work for a price of 7,700 ducats (1 ducat ≈ 11 reales), but the work had not been satisfactory. So it was decided to call in Leonardo de Figueroa, a resident of Seville, and Don Felipe de Unzurrúnzaga, a resident of Málaga, both master architects. It’s interesting that Ronda (annexed to the Bishopric of Málaga) always turned to Sevillian architects for help.

They found the roofing work insufficient and that its timbers lacked the required support, so it was in danger of collapsing. This was because the braces and quadrants were not properly constructed and because they were formed with only two rows of ribs, joined only by brick pillars. Finally, the brick pillars were not vertical and the ribs did not sit properly “according to good architecture”. In other words, the roof was not sufficiently strong in terms of its supports and was moving, thus leaking.

The conclusion was that most of the past work had to be removed and rebuilt, including also the flooring. For his part, master architect Francisco Gutiérrez Sanguino had requested a review of the lawsuit from the Granada chancellery. However, the latter decided to return the matter to the courts of the city of Ronda. They sided with the declaration made by master architects Leonardo de Figueroa and Felipe Unzurrunzaga, and offers were requested for the repair work.

It was also true that Francisco Gutiérrez was also participating in the construction of one of the city’s bridges, so the court asked the master builder if he wanted to continue with that work, despite his suspension as master builder of the church. He was given eight days to reply, and it would appear that the work to complete the bridge was also put out for offers.

In this regard, different bids and offers were submitted, one of which was made by Francisco de Castillo and the other by Sebastián de Espada and Bartolomé Pérez, on behalf of José Páez de Carmona.

The first offer was made in Ronda on October 31, 1710, before the Marquis of Casa Pabón, the city’s mayor, and the public notary. Francisco de Castillo, a master architect, was a resident of the city of Ronda, under whose responsibility and direction the jasper flooring of the main chapel was being laid. The master architect undertook to carry out the alterations, reconstruction, and repairs of the works as planned by the architects Leonardo de Figueroa and Don Felipe de Unzurrunzaga, “without missing anything, nor changing it or altering it in any way, using quality materials”. Likewise, he committed to repairing and finishing the two main doors of the church, including the bronze nailing and decoration that Francisco Gutiérrez had also agreed to do. This also included the sacristy doors, bolts, keys, and locks for all of them, in compliance with the master builder’s obligation. Finally, he stated that he would inspect and clean all the structural elements (transverse arches, capitals, architrave, frieze, cornice, etc.) that might have been damaged during the work, to leave the chapel perfectly finished at a total cost of 5,500 ducats.

Francisco de Castillo then presented a list of the quality of the materials and the discount he would have to make from the material left by the previous master. He agreed to complete the work within six months, starting with the first payment, corresponding to one-third of the total cost. The report presented by the master is very exhaustive, indicating that the work should not be carried out between November and March, as this was not a suitable time for work due to the harsh weather and rains of those months in Ronda. He proposed the months between April and October for the project. It was also noted that if the work did not begin until the summer, it would be damaged by winter rains, and that any costs incurred by this should not be borne by the grantor, and that additional funds would have to be provided to resolve the problem. Payments would be made, as was customary, in three installments. Three months after the first payment was made, the next payment would be due, while the final payment would be made upon completion of the work. It also stated that even if the payments were made in instalments, the money had to be released in advance to avoid delays in collection. Regarding the church and sacristy doors, once examined and appraised by a competent master carpenter, they were to be delivered to Francisco de Castillo to complete any work left unfinished by Master Carpenter Francisco Gutiérrez. The nailing and bronze ornamentation on the doors would also be assessed and deducted from the final payment. If the master carpenters appointed to inspect the work already begun reported that Gutiérrez’s execution was not of quality, nothing would be deducted. Likewise, Castillo promised that if the work, once completed, was not to the liking of the masters appointed to inspect it, it would be improved at his expense.

On February 19, 1711, an improved and new bid for the tendered work was presented to the Marquis of Casa Pabón, mayor of the city, and the public notary. This was the one submitted by Sebastián de Espada and Bartolomé Pérez, on behalf of and by virtue of a power of attorney from José Páez de Carmona, all masters and residents of Écija. The former represented himself, while the latter represented José Páez de Carmona, under a power of attorney that had been granted in Osuna on February 2 of that year before the town notary Andrés de Tejada. They set the cost at 58,000 reales de vellón (reales made of billon, or less than half silver), all with the same qualities, conditions, and obligations as Francisco de Castillo had set, without any variation, obligating themselves to carry it out and promising to provide guarantees to the city. The magistrate accepted the offer and ordered it to be announced. It was customary that when important works were carried out, they were announced in the most important cities in the surrounding area. What is truly striking in this case is the distance between Ronda and Écija (more than 100 km). It is probable someone close to the circle of master builders from Écija was in Ronda and informed them about the work that was going to be undertaken. The three master builders from Écija were people of recognised reputation, and holders of public offices.

Given the prestige of the bidders and the reduced cost of the work, the auction fell to the Ecija master builders. The notification took place in Ronda, where the master builders appeared before the mayor. The new, lower bid was announced, repeated several times, but no one appeared who could make a proposal other than the one raised by the Ecija master builders. For this reason, the auction was held with the aforementioned master builders, for the agreed-upon amount and with the qualities and conditions set forth.

The contracting process was very slow, as the necessary guarantees and mortgages for the execution of the project were not provided until 1718. Although the bid for the construction had been submitted in 1711, the work did not have to begin immediately, having to be delayed, perhaps because the craftsmen were foreigners and had to provide guarantees.

The work on the church must have been definitively completed in the 1720s, since in 1723 the decorative work was carried out by Esteban de Salas, according to the plans of Fray Miguel de los Santos. He had been responsible for carving the presbytery and the main altar, so his work seems to have been limited to finishing the decoration once the structural repairs were completed.

The intervention of the Ecija masters was therefore limited to resolving the structural problems. Extensive documentation exists about the methods of work, materials, and contracting in the 18th century.

What can we see today?

Most of the surviving altarpieces and sculptures date from the 18th century, as well as the magnificent choir stalls, completed in 1736, although by an unknown artist. These stalls, made entirely of walnut, originally featured twelve seats in the lower part decorated with litany of symbols and twenty-four in the upper part with various figures of saints and hagiographic stories. The organ, up on the left, was built in 1710 by Juan Félix Maureau from Granada and paid by a certain Francisco Martel Guerrero.

There are notes indicating that Felipe de Unzurrúnzaga also executed the carved plaster decorations, the altars of the chapel of the Virgen de los Angeles, and the choir stalls. This same report mentions the work of the architect José Martín de Aldehuela’s on the tower’s top, completed around 1793.

The lower part of the tower retains elements from the original mosque’s minaret, showcasing Islamic architectural influences. The middle section was reconstructed in the 16th century after the original tower was destroyed by a lightning strike in 1523. The upper section, added in the 18th century, is Baroque with its ornate decoration and a “cupulín“. This is a very small dome or lantern rather than a prominent cupola, which really can only be seen when visiting the roof of the church.

Entering through the small door in the back wall its a good idea to stop and turn around.

Above the entrance door, is a large mural of San Cristobalón (Saint Christopher), the patron saint of the city until 1954. The fresco is the work of the Ronda painter José Ramos. We have “Big Saint Christopher”, a common depiction as a giant figure carrying the Christ Child across a river. Christ is holding the “globus cruciger“ (cross-bearing orb), a Christian symbol of authority and cosmic dominion.

The above photo, and others later on this page, is taken from the excellent blog “Santa María la Mayor’s Islamic Roots and Catholic Grandeur“.

In 1954 a rare event occurred, Ronda changed its patron saint. In a formally declared act, involving both civil and ecclesiastical authorities, the city adopted “Nuestra Señora de la Paz” (Our Lady of Peace). It is said that this was part of a broader postwar Spanish religious revival, where Marian devotion, especially under titles like “La Paz” (Peace), was strongly promoted both liturgically and politically under Francoist Spain. This reflected a deliberate shift from a male, apotropaic saint to a Marian, civic figurehead, and her title carried symbolic national weight (peace, motherhood, unity).

It should be remembered that the devotion to Our Lady of Peace in Ronda dates back several centuries, though the exact origins and authorship of the image are unknown. According to local tradition, the statue may have been brought to Ronda by King Alfonso XI during his military campaigns in Andalusia in the 14th century.

In any case Our Lady was canonically crowned on May 15, 1947, in a large public ceremony in the Alameda del Tajo, attended by church and civic authorities. The coronation was approved by Pope Pius XII. In 1953, the city council of Ronda formally named her Honorary Mayoress for Life, and in 2003 she was symbolically given the keys to the city.

It’s worth noting that the canonical image of Nuestra Señora de la Paz (seen above), is not housed in the Iglesia de Santa María la Mayor. Instead, Our Lady is enshrined in Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de la Paz, located near Plaza de la Merced in Ronda’s historic centre.

Inside, the old basilica’s structure the floor plan consists of three naves separated by pointed stone arches on pillars with fascicled capitals decorated with cardina-shaped arches.

What we see above is the composite structure of the two columns, one Gothic and the other Baroque. We can’t see fully the Gothic pointed stone arches, but we can see the “fascicled capitals”, which just means a type of architectural capital (the topmost part of a column) found atop grouped or bundled columns. They were often richly ornamented with foliage, figures, or geometric motifs, and in Ronda reference to “cardina-shaped arches” has no sensible meaning, but might refer to the stylised acanthus leaves found on the capitals.

While the Gothic side naves are covered with ribbed vaults, the central one features hemispherical vaults on 18th-century pendentives, which are said to conceal the original Mudejar framework. These are just triangular segments of a sphere, which we can see in the above photo. They fill the gap between the arches and a circular dome placed over a square or rectangular space.

The later Baroque extension followed the design of the previous one, although with a notable difference in height. It’s divided into three separate naves, in this case, by slender pillars with juxtaposed Corinthian column segments. The walls have attached half-columns with prominent bases, between which open semicircular niches. It is said that the niches are divided by recessed ribs and a type of Mannerist-style keystone that replicates those already installed in Málaga Cathedral. This is only really visible if you look for it, and it doesn’t add much to the over impact of the interior architecture.

From the central vault hangs a wrought iron chandelier, with 34 lights, distributed in three levels of 18, 12, and 4 bulbs, respectively, with double garlands of 24,700 diamond-point crystals.

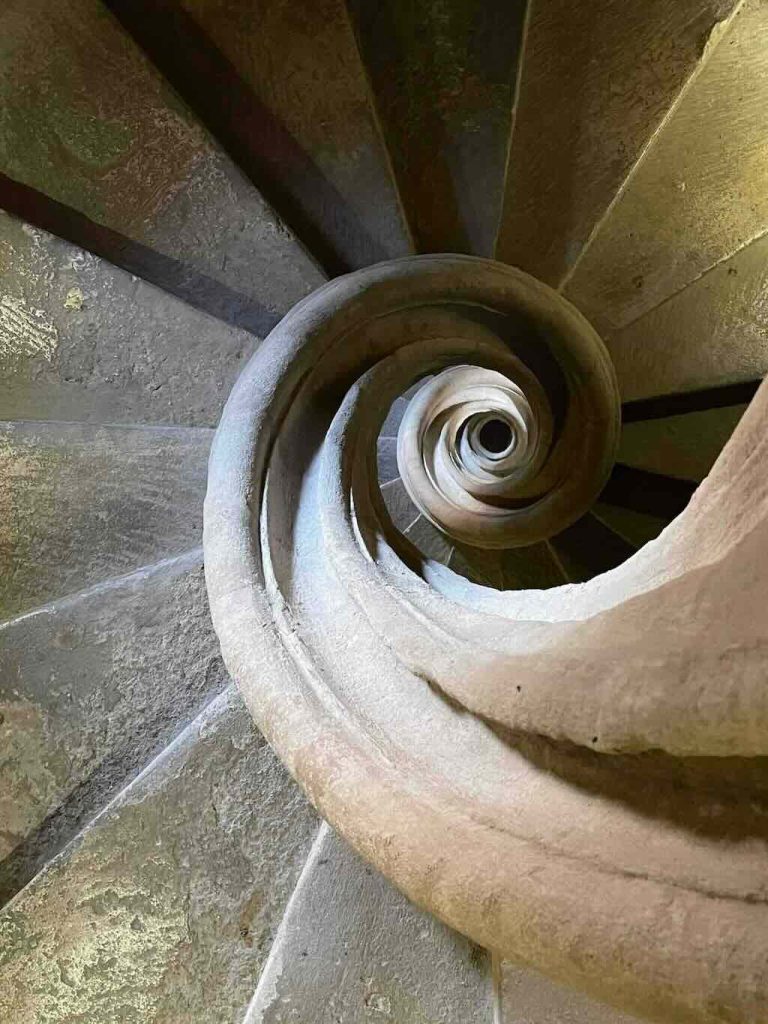

What is far more interesting is the following. It’s possible to climb up a spiral staircase and walk out on the roof. From there there is a small door leading to a narrow interior balcony (see the view below).

From this narrow interior balcony, you can see a wide entablature (the upper moldings around the wall), and below it a frieze. The central nave is covered with ribbed vaults flanking a central spherical cap on pendentives with eight ribs and a central medallion. The side naves, for their part, feature transverse barrel vaults accompanied by their corresponding lunettes.

It only remains for us to close the visit with a last view of the countryside taken from the roof terrace. We can see below us the Ayuntamiento de Ronda (Ronda Town Hall), and just behind the façade of the Santuario de María Auxiliadora.

In the distance we can see the hills of the Parque Nacional Sierra de las Nieves. and the fresh white houses nearer to the city is the modern residential area Urbanización Las Quinientas.