Ceramics are probably the oldest form of technology, and it probably didn’t take long for someone to suggest that we were all born of a primeval clay and created by a “divine potter”.

Some people might express a passion for pottery, or a desire to become a potter, but we all appear to accumulate far more pottery and porcelain than we plan for or need. A small part of our collection of pottery and porcelain is used daily, but the vast majority, valuable or not, is stacked away in draws and cupboards, or very occasionally hung on walls or given pride of place on a sideboard or mantlepiece. Almost all pottery and porcelain is ignored, until it breaks.

My wife Monique, the love of my life, left this world on the 23 December 2023. One way to deal with my loss was to focus on what we had planned to do. And that was to down-size, rationalise, redecorate, and that meant making explicit decisions to keep, or not keep, things, including the pottery and porcelain accumulated over near 50 years of living together.

This post is about the pottery and porcelain items that I decided to keep.

Check out my little posting on Beer Steins.

And I also have recently added a few new plates to Monique’s little collection of Niderviller Pottery.

Arzberg porcelain

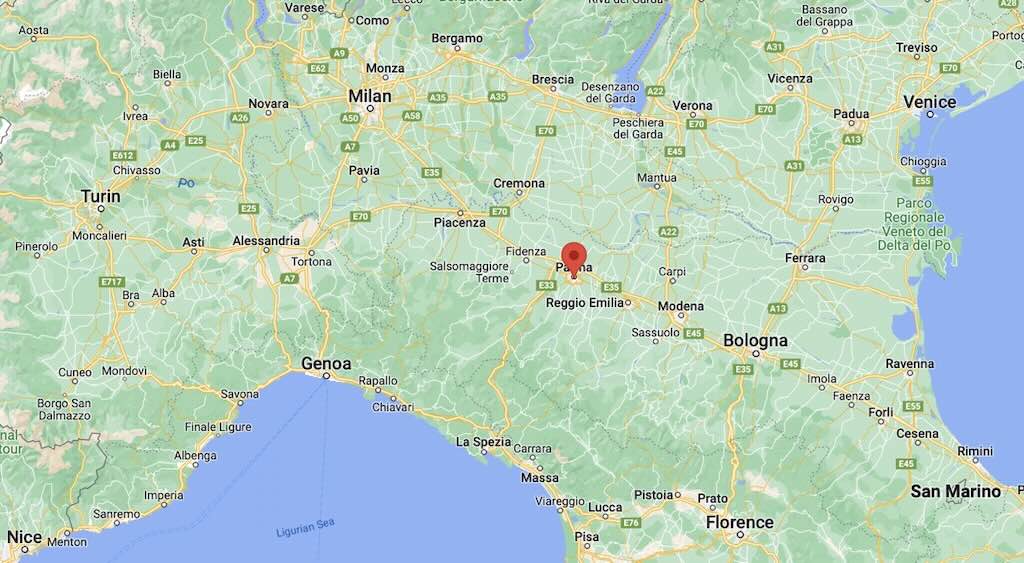

In 1976 my wife, as a mark of our decision to live together, bought a small ski apartment in the Val d’Aosta. The fun part, besides skiing every weekend, was looking for discount deals on the furniture and fittings. And this including buying a collection of kitchen porcelain, etc.

This collection of plates, servicing dishes, cups, saucers, tea and coffee pots, etc. has survived almost intact. Only the breakfast-style flat plates have taken a major hit (down to 5 from 12).

We bought an entire set (in the new-year sales) of simple German Arzberg porcelain with Hutschenreuther Group stamped on the base (now owned by Rosenthal). On the base there are two numbers, always a “6” to the right of the makers mark, and a number 2, or 3, or 4 on the left. The “6” might be the pattern “Cruppe 6”, which might have been produced between 1970-79.

There is an arzberg-porcelian website, indicating that it has been integrated into the Rosenthal and Thomas ranges. But our particular model appears to have disappeared.

Arzberg was recognised for its simple design free of unnecessary frills. And I think that the design has remained very contemporary.

I’ve not been able to find on the auction sites this exact model with its unique style of handles.

Raphael's Putti

In Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, there hangs the famous Sistine Madonna, an oil painting by the Italian artist Raphael. Sitting on the bottom of this painting, one of the last Madonnas painted by Raphael, are two winged angels. They are usually known as putti, and are commonly conflated with cherubim.

This is not the topic of this post, but not all putti have wings, and equally putti are not angels.

Let’s now turn our attention to the Martciä di Barradzüe (in the local patoué Valdôtain) a flea and antiques market that takes place every year after mid-August in the centre of Morgex.

Sometime in the early 1980s we saw a pair of small painted plaster panels cast in relief. The two panels together were a copy of Raphael’s putti.

We fell in love with them, bought them, and they have hung in pride of place over the chimney in our mountain apartment ever since. They have no monetary value, but Monique loved them, and they will stay with me until I die.

Pot aux rugbymen

I have no idea how this reasonably sized, but boring grey, pot came to be on our shelves. I can only assume that it was once owned by my wife’s parents, or more likely grand-parents. It has lived with us for certainly 40 or more years, and its sole purpose was to store stuff that we never needed. To do this it hid away on a back shelf, led a very discrete life, and survived (with its contents intact).

Before deciding to downsize it, and its contents, I did a quick search on what this simple looking pot might celebrate.

Surprise, surprise, it turned out to have a brother in a museum. Albeit not a premium museum, but our pot is nevertheless one item in the “Arts Décoratifs” collection of the museums of Boulogne-Billancourt, a wealthy and prestigious commune in the western suburbs of Paris.

It is from this museum that we learned that it’s called “Pot aux rugbymen” (a Rugby-men’s Pot), dating from the 1927-1930. It was created by Émile-Just Bachelet (1892-1981), a French sculptor and ceramist. According to the museum Bachelet worked in the ceramic workshops in Boulogne of the well known French post-Cubist ceramist André Fau (1896-1982) and the artist Marcel Guillard. The museum website mentioned that Marcel Guillard died in 1983, however other websites mention that he died young in 1932.

The museum description stresses that Bachelet tried to celebrate the collective effort and athleticism associated with rugby, which quickly became popular after its introduction in France in the 1870s. The description goes on “Its stylised and powerful forms unfold in a frieze marked by modernity the action of the scrum which animates the players in search of the ball”.

On the base there are some incised markings, namely Bechelet Se, Boulogne (and possibly the numbers 3/6), and finally a rectangular “MADE IN FRANCE”.

Perhaps the most intriguing thing is that the museum presents the “pot” without its lid, whereas we have the lid as well. I actually contacted the museum and sent them a photo, and they were pleased to learn that this pot actually once had a lid.

Keller et Guérin à Lunéville

A few years ago whilst again strolling through the Martciä di Barradzüe in Morgex, my wife spotted two small decorative plates. Not my “cup of tea” but when Monique wanted something she usually got it. Not a mega-purchase at €5/plate, they finally found a place hanging in a small alcove.

Now that Monique is no longer at my side, everything she liked now takes on a new sentimental value. Faced with the decision “keep, don’t keep” I decided to do a little detective work.

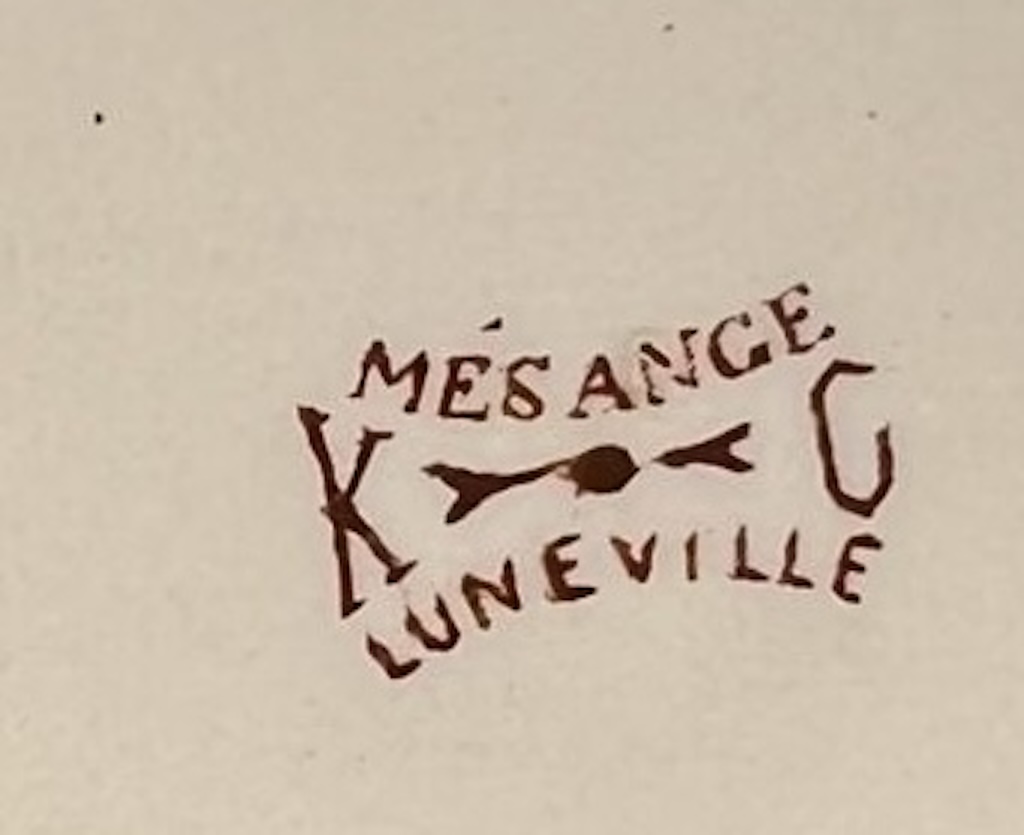

One of the plates had a makers mark, along with a coloured artists mark and an incised mark. The other plate also had the same coloured artists mark and an incised mark, but no makers mark. As seen above the two plates were clearly a pair.

Above we can see the makers mark for “Keller et Guérin” (K-G) from Lunéville, a commune in the French department of Meurthe-et-Moselle. Lunéville is now little known, but once was the capital of Lorraine, and for a period was known as the “Versailles of Lorraine”. Just to stress the resorts past glory, the Treaty of Lunéville was signed there in 1801 between the French Republic and the Austrian Empire by Joseph Bonaparte and Count Ludwig von Cobenzl.

Lunéville faience, a kind of unglazed faience produced from 1723 at Lunéville by Jacques Chambrette, became the Manufacture Royale du Roi de Pologne (“Royal Factory of the King of Poland”) in 1749. The earthenware first became famous for its detailed figurines and in the 20th century for its art deco designs, and it still exists today as “Terres d’Est“.

We can also see that the model was Mésange, which is the vernacular name in French designating different groups of passerines (the direct translation of Mésange is Tit).

The artists mark is a small painted sign that looks somewhat like an arrow-head, and the incised mark is difficult to decode but included the number “6” or “9”. Several sources date the Mésange model to the late 19th century.

The two examples shown above are taken from a catalogue, and in fact some variations can be seen with our examples (seen below). Our plates have significantly less intense, more natural colours, for example, the tail feathers are a light grey, and most of the foliage is green rather than brown. On one plate there is an additional branch with flowers, so some quite distinct design differences.

Not my favourite style, but they are growing on me, even if they are still hanging in the same small alcove.