In my first post I looked at why I started again to try to organise my postage stamps. After 50 years I had to learn a new vocabulary, and understand how to judge the quality of each of my postage stamps. In this post I try to apply everything I’ve learned to arranging my boxes of old stamps.

Introduction

As a kid I had a collection of postage stamps. I had my album with a country and/or year on each page, and I carefully displayed my stamps each with its stamp hinge (I’ve read recently that hinges are a bad thing). Today I’m certainly not a philatelist, nor even a stamp collector, but I still remember enjoying myself sifting through an old shoebox of used stamps looking for the best ones to display in my stamp album.

Fast forward more than 50 years, my wife and I finally decided on a “clean up or throw out”. I almost threw out those old stamps, but finally they were promoted to the “clean up” list. Looking back the logic escapes me, but those stamps represented different periods of our lives, in the UK, then Italy, Germany and France, before landing in Luxembourg, and more recently wintering in Spain.

And there is something rather compelling about handling a small piece of colour paper that was purchased more than 100 years ago, was attached to an envelope, did its job and travelled to a far-away destination, was cancelled and declared useless, and yet somehow survived until today.

My plan was to go through the boxes of stamps (when needed, soaking the stamps off the old bits of envelopes, etc.) and arrange them in a couple of albums. Not collecting, just organising and arranging what was in the boxes. My idea was that once I could isolate the decent looking stamps, they would just fit in one or two albums (I would bin the rest). As they say “done and dusted”.

Adding some old stamp collections gifted from friends, plus mistakenly buying a job lot of a few kg’s of world stamps for less than €100, my imaginary shoebox of old stamps rapidly grew to weigh about 25 kg, fortunately with a lot of sheets, folders, albums, envelopes, etc.

Enough to keep me going, until I got bored.

Since I knew I would eventually get bored, the challenge was to at least focus on arranging some of the stamps in a coherent and interesting way. Leaving the rest for the next rainy day.

First steps in the long road to arranging my postage stamps

In my first post I tried to understand how to assess my postage stamps. The next question was how to organise them?

Despite the fact that I’m not really collecting stamps (just arranging some of those I had accumulated over the years), here are a few points I picked up quickly:-

- By default I had accumulated both mint and cancelled postage stamps, so I would need to organise both.

- There was no focus on any particular country or any particular topic (although I had a lot of stamps from the United Kingdom, Italy and France).

- I quickly learned that I should never permanently affix stamps to a page, and I should remove any hinges still stuck to stamps (some were easy, some less so).

- I needed to buy something to keep the stamps nicely organised and protect them from damage (e.g. are stock-books the best option, and if so which ones?).

- I learned that all materials that comes into direct contact with stamps and covers etc. should be made of archival quality materials. For album pages and mounts this meant alkaline buffered paper, free of lignin and ground wood, and protectors (pockets, sleeves or envelopes for album pages etc.) of chemically inert polyester, e.g. Melinex®, Mylar™ without surface coatings or plasticisers. At the same time I learned that good quality stock book pages and binders, etc., are incredibly expensive.

- “Sort before soaking”, because bit of envelopes are easier to sort, and it avoids soaking stamp I don’t want to keep.

- I also bought a stamp drying book, a small magnifying glass, and a pair of tweezers. Initially I through this was a bit “over the top”, but they all turned out to be fantastically useful.

How should I organise my stamps?

What to keep and what to throw?

But if a single used Italian definitive has a catalogue value of say 30 cents, then 50 of them are worth €15. So is it logical to throw away maybe €10-12 worth of stamps? Of course, they only have that value if put on the market, and a buyer is found. And it might cost someone too much in time and effort to advertise and sell one stamp for 30 cents, plus postage. The potential seller might have more interesting and useful things to do than try to sell cheap stamps individually.

Reading through the blogs, etc. it is evident that catalogue prices are almost always inflated. Many experts suggest that the real value of a stamp worth 30 cents in a catalogue is significantly less than 10 cents in the open market. It really only has a value when sold in a packet of 100 Italian stamps (mixed with a few duplicates) for offers of between €5 to €10. And remembering that in online sales, generic worldwide stamp collections can sell for 1-2 cents a stamp. I recently bought more than 2,000 ill-defined worldwide stamps in a ‘collection’ for well under €100, including postage and import duty. But a well-curated pre-1900 album can still sell for a €1,000 or more.

Another aspect of online postage stamp catalogue prices is that they are less ‘retail prices’ based upon market values (sales, auctions, etc.), than ‘perceived value’ (sometimes called ‘reference value‘). A private individual won’t get the retail value from a retailer. The retailer will expect a profit, and factor in how long they have to hold the stamp before finding a customer. Many catalogues will not drop below 20 cents for a stamp, based simply upon the time it would take a dealer to assess the condition and value of a given stamp. Also catalogue prices are based upon undamaged stamps in VF condition, anything less will sell at a discount (or not at all).

A ‘reference value’ is higher than the retail value, sometime even the double, and quite often 50% more. Some catalogues are owned by auction houses, who have an interest in stabilising prices to ensure that the buyer and seller arrive at a decent (possibly predictable) price. Other catalogue providers actually sell stamps, and provide guarantees that the stamps are in very fine (VF) condition. Yet other catalogues offer an expertising service with a certificate, and the fee is based upon a percentage of the list price of a stamp in their catalogue. Finally some people suggest that lowering prices in catalogues will negatively impact catalogue sales.

So what do I do with those one hundred Italian definitives? One collector wrote that he would throw away stamps that were torn, badly creased or thinned. But even that decisive statement leaves a lot unsaid. What was “badly”? What if only part of the stamp was thinning? anyway, what exactly is ‘thinned”? What about colour fading, or spots? What about centring, or the quality of the perforations? Did they have different criteria for stamps that were 100 years old, and for others that were 10 years old? What if it was their only example?

I’ve seen people who inherit stamp collections wanting to bin anything that is not valuable. Many collectors protest, suggesting that the stamps should be given to stamp clubs. Collectors often note that “making money” is not their objective, stamp collecting is a hobby, sometimes a passion, and almost never an investment.

Another collector would throw away stamps with heave cancellations. But what about those who collect cancellations, light or heavy? In fact Wikipedia has a page on cancellations, and mentions that bullseye cancellations are popular with some stamp collectors because of their neatness and the fact that the time, date, and location where the stamp was postmarked may be readily seen. However, modern machine cancellations are normally arranged so that the wavy lines, slogans, or other killers are applied to the stamp, leaving the postmark clear on the envelop.

And what about precancelled stamps? This is a postage stamp that has been legitimately cancelled before being affixed to mail. An approach typically used by mass mailers, who can save the postal system time and effort by prearranging to use the precancels. In fact there are collectors of precancelled stamps, and at least in the US there is even a precanceled society (see the spelling difference). Personally I don’t like the rather brutal precancellation marks left on the stamp.

Then there are watermarks, with visually identical stamps having different watermarks, and possibly quite different values.

OK, once I’ve purged my collection of one hundred Italian definitives, I might still have 30-40 of them that look more or less the same. What to do with duplicates? Of course much depends on how many duplicates. Some collector look to donate them, swap them, or trade them. Other collectors sort them and store them in stock-books. As one collector asked just how much time people were willing to spend to organised worthless duplicates?

One collector mentioned having over half-million duplicates, so I don’t think a few hundred duplicates in a stock-book is going to pose a problem. Of course, another collector rightly noted that the only stamps he wanted duplicate of, were too expensive for him anyway.

Back to the real world

I need to focus on arranging the stamps in my shoeboxes…

I will arrange my stamps, by nation, and chronologically. I will include both mint and cancelled stamps, and include space for interesting duplicates. I will leave a limited number of spaces for missing stamps within sets, in part because I don’t yet know what else is in my shoeboxes. I will also leave a limited number of spaces for missing sets, etc.

I must be careful about mint-looking stamps that are not really mint (for the collector) because a mark from a hinge can be seen, or its possible to see that the gum has been washed off.

I will keep all old stamps, mint or cancelled, which are sound, appealing to the eye, and well centred. But if they are really old, I might just keep them all!

Getting my hands dirty

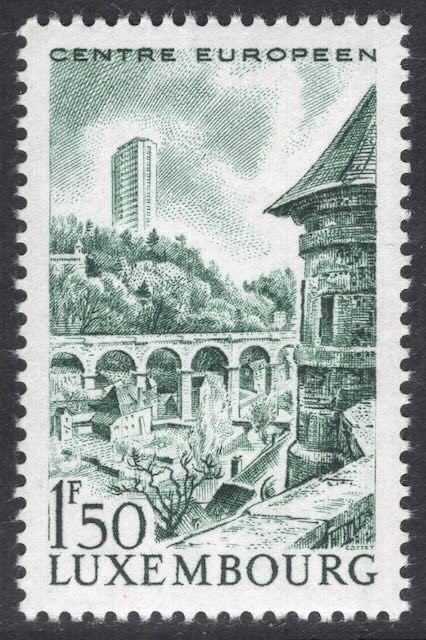

The real test of what is written above is to actually sit down and do it. I decided to apply “my rules” to build a collection of stamps for Luxembourg. The reason was simple, I’ve been a resident there for some years, and I had seen quite a number of Luxembourg stamps scattered through my 25 kg of albums, stock-books, pages, envelopes, etc. I knew there was quite a variety of stamps in my ‘collection’ dating from the late 19th century, through the occupation of Luxembourg during WW II, and including the move from the Luxembourg Franc to the €. I also had two semi-populated Lindner albums to start me going (but only with mint stamps for a limited number of years).

The first problem was simply to finds all my Luxembourg stamps hidden within a ‘collection’ of 25 kg of stamps. At this moment neither my Lindner albums nor online catalogues helped. I just had to scan through all the old albums, pages, stock-books, etc. trying to spot the word Luxembourg.

Finding the odd 19th century or early 20th century Luxembourg stamp was problematic, simply because they are small, delicate, look similar to many other postage stamps of the period, and the word ‘Luxembourg’ is quite small and often partially hidden under the cancellation.

Finding more modern Luxembourg stamps was easier because the font use was larger, and the name being long, it occupied more space on the stamp making it easier to see.

However, scanning through 1,000's of stamps, etc. got me thinking!

Was the ‘Penny Black‘ really the first postage stamp? Issued in the United Kingdom on 1 May 1840, it was the world’s first adhesive postage stamp used in a public postal system. In fact an affordable postal service in England started back in 1680, initiated by an entrepreneur in London named William Dockwra. He established the Penny Post, which delivered letters within London and a 10-mile radius around the city. People paid a penny when they received the letter. The Penny Post offered collections at nearly 600 locations within London, and attempted delivery several times a day. The idea proved popular, but not foolproof.

It was not until 1635 that a general or public post was properly established, an event which “may properly be regarded as the origin of the British post-office”. As a result, the Penny Post was taken over by royal authorities in 1682 and became part of the existing General Post Office (already created in 1660). From that point on, the postal rates gradually increased as the monarchy used the profits from the Government Post Office and the London Penny Post to pay for several wars with France. At one point, it cost what many would have considered a day’s wages to send a letter across London.

You had to be rich and patient to use the Royal Mail. Delivery was charged according to the miles travelled and the number of sheets of paper used. A 2-page letter sent from Edinburgh to London, for example, would have cost 2 shillings, or nearly £10 in today’s money. And when the top-hatted letter carrier came to deliver it, it was the recipient who had to pay for the postage. Letter writers employed various ruses to reduce the cost, doing everything possible to cram more words onto a page. Nobody bothered with heavy envelopes, instead, letters would be folded and sealed with wax. The sender then had to find a post office, because there were no nice red pillar boxes. And the sender had to hope the recipient didn’t live in one of the several rural areas which were not served by the system. The letter would arrive after several days, and might well have been read or censored.

This went on for more than a century, before an educator and inventor named Rowland Hill came forward with the “preposterous” idea of a prepaid stamp that cost only a penny (per half ounce or 14 grams, without regard to distance). It would constitute a sizeable drop in the cost of postage, but Hill argued that if common people were given the means to use the postal system, the increased volume would more than offset the slash in price. He was only partially correct. Over the next year, 70 million letters were sent. Two years later, the number of letters sent with a penny stamp had more than tripled. However, despite its popularity, it took decades for the new postal system to make as much money for the government as it had before it had decreased the price of postage to a penny.

On 10 January 1840 the Uniform Penny Post started, charging only 1d for prepaid letters and 2d if the fee was collected from the recipient. Fixed rates meant that it was possible to avoid handling money to send a letter by using an “adhesive label”, and accordingly, on 6 May 1840, the Penny Black became the world’s first postage stamp in use. Adhesive stamps had already long been in use to show payment of taxes.

Here is a very interesting Penny Black guide.

The penny post changed the nature of the letter. Weight-saving tricks such as cross-writing began to die out, while the arrival of envelopes built confidence among correspondents that mail would not be stolen or read. And so people wrote more private things, for example, politically or commercially sensitive information or love letters.

Why did the Penny Black have the Queen’s portrait on it? Hill immediately held a competition to design the first stamp. There were some 2,600 entries, but none was considered suitable. Finally Hill endorsed a depiction of Queen Victoria’s profile based on a design that William Wyon had created for a medal to celebrate her first visit to London earlier that year.

Who decided that the Penny Black should be that particular size? Initially, Hill specified that the stamps should be 3/4-inch square, but he altered the dimensions to 3/4-inch wide by 7/8-inch tall to accommodate the writing at the bottom. The word “POSTAGE” at the top of the design distinguished it from a revenue stamp. “ONE PENNY” at the bottom showed the amount prepaid for postage.

The two lower corners showed the position of the stamp in the printed sheet, from “A A” being to top left position to “T L” being the bottom right. The sheets consisted of 240 stamps in 20 rows of 12 columns. This meant that one full sheet cost 240 pence or 1 pound, and one row of 12 stamps cost a shilling. Eleven printing plates were made for the stamp. Each of them were slightly different in terms of the lettering used and the insignia on the stamp. Experts can tell exactly which plate each stamp came from, but it is a laborious process.

Why was the Penny Black just black? I guess black was the obviously “printing press” colour, but in fact despite the Penny Black’s popularity, it lasted less than a year. At the time, cancellation marks were in red and difficult to see on the black design. Because the red ink was easy to remove, it was possible to re-use canceled stamps. In February 1841, the Penny Red was introduced, with the same design printed in brick-red ink. The post then began using black ink for cancellations, which was more effective and harder to remove. The Penny Reds continued in use for decades with about 21 billion being produced.

Why is the stamp placed in the top right-hand corner of the envelope? The decision was made because more than 80% of London’s male population was right-handed, and it was believed this would help expedite the cancellation process.

Why didn’t the Penny Black have the country on it? The stamp was originally for use only within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and as such was, in effect, a local stamp. For this reason the name of the country was not included within the design, a situation which continued by agreement with foreign post offices, provided the sovereign’s effigy appeared on the stamp.

What about the quality of the Penny Black perforations? Each Penny Black stamp came embossed with a small crown watermark, but they were ‘imperforated‘, with each Penny Black cut from the sheet with scissors. This was time-consuming and error-prone.

So the Penny Black is incredibly valuable? Not so quick. There were more than 68 million produced during the one-year print run. It’s iconic, but not exactly a rare stamp because around 1.3 million are estimated to still exist. This 2% survival rate is probably higher than would be expected because the use of envelopes was unusual in the 1840s. Consequently, the stamp and the address could be found on the obverse of a letter, which was folded and sealed with wax after being written (so-called letter sheets). People kept the letters, and thus kept the stamps.

The Penny Black had to be cut out of sheets, and some were badly cut whilst others had four large margins. A penny black in fine condition with four margins, will be worth £200 or £300. Stamps with one or two good margins will probably be as little as £30. What collectors want are exceptionally good looking Penny Black’s from particularly rare plates.

What is the world’s second oldest postage stamp? Perhaps not so surprising is that the next oldest stamp is the Two Penny Blue. What’s more surprising is that it was issued only 48 hours after the famous Penny Black. And because only about 6.5 million of them were printed it is in fact rarer than the Penny Black.

Which was the second country to issue postage stamps valid within the entire country (as opposed to a local issue)? Surprisingly it was Brazil, who issued the “Bull’s Eyes” stamp in 1843 (the name comes from its distinctive appearance). And, like Great Britain’s first stamps, the design did not include the country name. The third country to issue postage stamps was Mauritius, a small island in the southwest Indian Ocean. Its first two postage stamps issued in 1847, called the “Post Office” stamps, are of legendary rarity and value. The unique cover bearing both “Post Office” stamps has been called “the greatest item in all philately”. Then came France, Bavaria, and Belgium in 1849.

Did they all copy the design of the Penny Black? No, the Brazilian “Bull’s Eyes” looked nothing like the Penny Black, whilst the Mauritius stamps looked like copies of the Penny Black (but were orange and dark blue), which is not surprising because it was a Crown colony at the time. France first used the head of Cérès, Bavaria a simple quadrangular design, and Belgium a frontal view of King Leopard I.

Who issued the first bi-coloured stamp? This looks like a simple question, but it opens up the much more complex question about the colour of postage stamps. Initially, countries typically made a random choice of colours for denominations. In 1896, the members of the Universal Postal Union agreed on green, red, and blue as the standard colours for standard printed matter, postcard, and letter rates, respectively, when sent abroad. This convention was gradually abandoned as inflation created too many exceptions from the 1930s and onwards. Stamps with two colours (“bi-coloured”) began to appear very early, although typically reserved for higher values, due to the added expense of multiple print runs.

Several of the essays for the first postage stamp (the Penny black) were for a bi-coloured stamp, but they were rejected as too expensive to produce and too hard to print. Postage stamps are essentially small scale bearer bonds or pieces of currency. Anyone who had one was entitled to the value of the service that it represented. The earliest objections to issuing stamps centred on counterfeiting and cleaning and re-usage of stamps. Because of this concern, early stamps were engraved, which was the printing process of two centuries ago that was hardest to reproduce illegally. Intaglio (engraving) printing presses were expensive and the creation of stamp dies was artisan’s work. The raised ink on the stamps from engraved printing meant that even casual stamp users could know if they were handling the genuine article.

Engraving meant that the additional expense of bi-coloured stamps was not necessary from a security standpoint, and for the first seventy years, it was largely souvenir stamps that were printed in more than one colour.

I’ve not found the first bi-colour postage stamp, but the Indian 4-anna stamp of 1854 was the first bi-colour stamp produced and sold in the British Empire.

And now... back to Luxembourg

After wandering off with questions about the Penny Black, its time to get back to deciding about my early Luxembourg stamps. Above is a selection scraped from the Web, but mine were just as bad, if not worse.

There appears to be at least three different ways to view a collection of old stamps. There are the two extremes, and a more technically oriented middle-way.

One extreme is to keep almost everything, except for the occasional really, really poor example, that is in any case just a duplicate. This type of collector might be interested in stamps through to the 1950s because there were many variations, some of which are yet to be discovered. They view damage as being part of the life of stamp, it did its job (one collector called them “wounded warriors“). And another collector pointed out that “one man’s trash can be another man’s treasure”.

The other extreme is to bin almost everything, on the basis that most are worthless. There are few rare exceptions, but it’s not certain that an amateur collector would recognise them anyway. This type of collector would only keep one or two examples of a “fine” stamp (e.g. without noticeable flaws, have average centring, light hinge marks, etc.), or those with interesting cancellations, or any poor quality rare examples. They would bin all additional “fine” examples of common stamps, on the basis that they are worth next to nothing. Old does not mean valuable, and they would certainly bin any old stamp that was ugly or faulty. Ugly or faulty means tears, perf trims, thins or scuff marks. This type of collector would probably bin almost every damaged or common post-war stamp. One collector mentioned only keeping stamps that had a catalogue value of $50 or more, and he would bin the rest (bit dramatic for me). He appeared to also focus on damaged high-value stamps that could be sold at a discount.

The reality is that collectors must always face the question what to do with a “damaged” stamp. Let’s first use three working definitions, namely:

- Superb – These stamps are of the finest quality. They have near-perfect centring, brilliant colour, and perfect gum.

- Fine – These stamps are without noticeable flaws, have average centring, light hinge marks, yet aren’t quite as fresh as those defined as superb.

- Good – These stamps are noticeably off-center, but still fairly attractive with minor defects, thin ares, and heavy hinge marks.

The middle-way is to look at the centring, the condition, the gum, and the rareness.

If we look carefully at the above stamps, none are “Superb” and none are rare. Of the 30 stamps, there are at least 6 stamps that are damaged, and could be binned immediately. Maybe 7-8 are reasonably well centred with decent margins, and 7-8 stamps have acceptable perforations, but they are not the same stamps. The colour on 4 or 5 stamps looks reasonably fresh, the rest look faded. More than half of the stamps have unpleasant looking cancellation marks, and none of the cancellation marks are worth keeping.

The reality is that none of the above stamps are “Fine”, and my guess is that between 5 and 7 are “Good”, and anything below “Good” isn’t worth keeping. At one end of the spectrum a collector might decide to keep around 20 of the above 30 stamps, whereas at the other extreme, none would avoid being binned. The middle-of-the-road collector would probably keep around 10-15 of the stamps, but hope to replace all of them with better examples.

In the above photo, the one thing that is hidden from our view is the condition of the reverse, the quality of the gum, any hinge marks, and thinning. This page on Gum Basics is worth a read, as is “Grading Guide – Determining Soundness“.

Another topic that is rarely discussed is foxing or rusting on stamps, and here is a very useful discussion on the topic.

So do I keep a grotty stamp, because it’s the only example I have? The simple answer is probably yes, but maybe not! Depends on the day! Remember I’m arranging my stamps, not collecting, so I don’t need to think too much about the finer points of stamp collecting philosophy.

Let’s look at the problem of duplicates again. I guess this follows on from having gone through all the stamps of one particular type and denomination. All the ‘rubbish’ has been binned, and the best example(s) have been isolated. What was left were decent-looking duplicates, with little or no real street value. The question was, do I keep some of these ‘extra’ decent-looking duplicates, or none of them, or all of them?

In fact I had decided that lower quality duplicates of older stamps (say pre-WW II), along with decent-quality duplicates of modern commemoratives, would go in a stock-book.

There may be a logic to keeping duplicates. That is the intention to study them for flaws or even the possibility to discover unexpected value.

The World Stamps Project has a very interesting page on “Postage stamp flaws, errors and types“. It divided variations into those reoccurring, those coincidental, and those that derived from changes in materials or in the ways the materials were used in production (colour, paper, gum, perforation, typography, etc.). Herein lies the challenge. Checking the whole collection of duplicates of a particular stamp for variations that might prove interesting, or even valuable.

Wikipedia has a page entitled “Errors, freaks and oddities“, and Find Your Stamps Value has a very useful page on Stamp Errors, with lots of detailed examples. The page “Errors freaks, oddities and blunders” from Linn’s, goes one step further in listing examples “from the sublime to the ridiculous”.

But perhaps the best type is discussion is outlined in “When expertizing high-value damaged stamps makes sense” which takes a sensible view on old but damaged stamps. The same site hosts a page “The possible problems lurking in your stamp collection“, also about how to evaluate stamps that have sat in a collection for sometime.

The perforations themselves can also be flawed, but frankly it’s a very complicated topic. This discussion on “Irregular Compound Perfs” highlights just how complicated collectors can make it. At times it reads as if they are discussing the number of feather on the wings of a particular angel. However, it is one of the most information pages I’ve seen in a long time.

To close off this discussion on examining all duplicates, check out this page “The Rare Stamps Error Collection“, looks at stamps that should never have existed.

Once I had ‘decided’ on what to keep and what bin, I then had to look at the problem of fakes. This fantastic webpage summarises in some detail the types of forgeries that are seen on the early Luxembourg “coat of arms” stamps.

Not specifically to Luxembourg stamps, but just to make things even more interesting, there are some excellent forgeries out there. In fact forgeries by Jean de Sperati are collectable in themselves because of the high quality craftsmanship employed.

I will, one day, come back to my Luxembourg stamps in a separate post. But for completeness I want to register here links to Luxembourg Philately by Gary Little and Luxembourgian Philately.

Last word - a final example

I have more than 100 examples of this particular denomination. It is the Italian 25 Lira Siracusana, introduced in 1953 and only replaced in 1980.

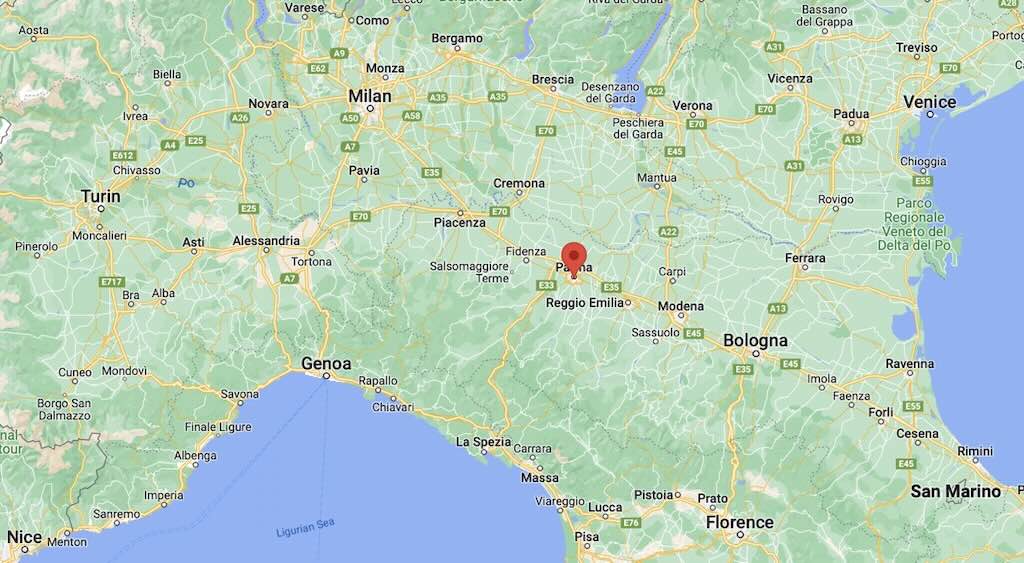

I’m guessing, but one of the postmarks is surely worth keeping, because it’s clearly from Occimiano, a comune (municipality) in the Province of Alessandria in the Italy.

With the three cancellations, the right-hand example is very light and worth keeping, whilst on the left it’s heavy and not worth keeping. I would also not keep the middle example, because the franking is across an important part of the image on the stamp (across the eye), despite the origin and denomination of the stamp being clearly visible.

But … and there is always a but.

There are some variations associated with the watermarks. For example, it’s possible to find a 100 lire stamp with a rare type of watermark, with a catalogue value €6,500 mint and €110 used. The same denomination with another watermark, and the catalogue value would be about €0.25, either mint or used.

For a beginner like me, I might never have thought about watermarks. Or I might have checked them, but not seen the odd-one-out. I probably wouldn’t have found the difference in a catalogue, and I might not have thought to check with an expert on one of the specialist websites.