In late 2024 I went on an explorer cruise to the Antarctic. And going to the Antarctic meant going through Buenos Aires. I had never been to South America, so I decided to include some days before and after the cruise to do some sightseeing.

This post is Part III, describing (or more truthfully, inspired by) my visit to Buenos Aires in November-December 2024.

Visiting Buenos Aires (Part I)

Visiting Buenos Aires (Part II)

Visiting Buenos Aires (Part III) including:-

- What About the Silver Route Through Buenos Aires? (a repeat from Part II for context)

- Buenos Aires and the Silver Trade (official & smuggling) in the 17th Century

- The Role of Buenos Aires in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- Buenos Aires – from Colonial Port to Cosmopolitan Capital

- La Boca – Buenos Aires’ First Gateway to the World

- Las Cantinas in La Boca

- Caminito – what was, what is…

- A Dialogue Between Puntín and Caminito, Like Two Old Friends

- Caminito – A Manufactured Attraction

- Parque El Rosedal

- El Ateneo Grand Splendid

- San Telmo Market

- The History of Puerto Madero

- Puerto Madero Today

- Parque Thays

- Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo

- Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

- Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

I have a separate blog post for my visit to the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

This post is also one of a series describing my entire trip, including:-

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 1-7)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 8-11)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 12-17)

- Planning a Cruise to the Antarctic

- My Antarctic Packing List

- Le Lyrial – A Luxury Expedition Cruise Ship

- Le Lyrial – Exploring Hidden Engineering

I have also reviews about my travel arrangements:-

- Air Dolomiti Embraer E195

- Lufthansa Business Class Lounge, Frankfurt

- Lufthansa Boeing 747-8 – Business Class

- Ministro Pistarini International Airport, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Meliã Recoleta, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Sofitel Recoleta, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Palladio, Buenos Aires

- Lufthansa Boeing 747-8 – First Class

- Lufthansa First Class Lounge, Frankfurt

What About the Silver Route Through Buenos Aires?

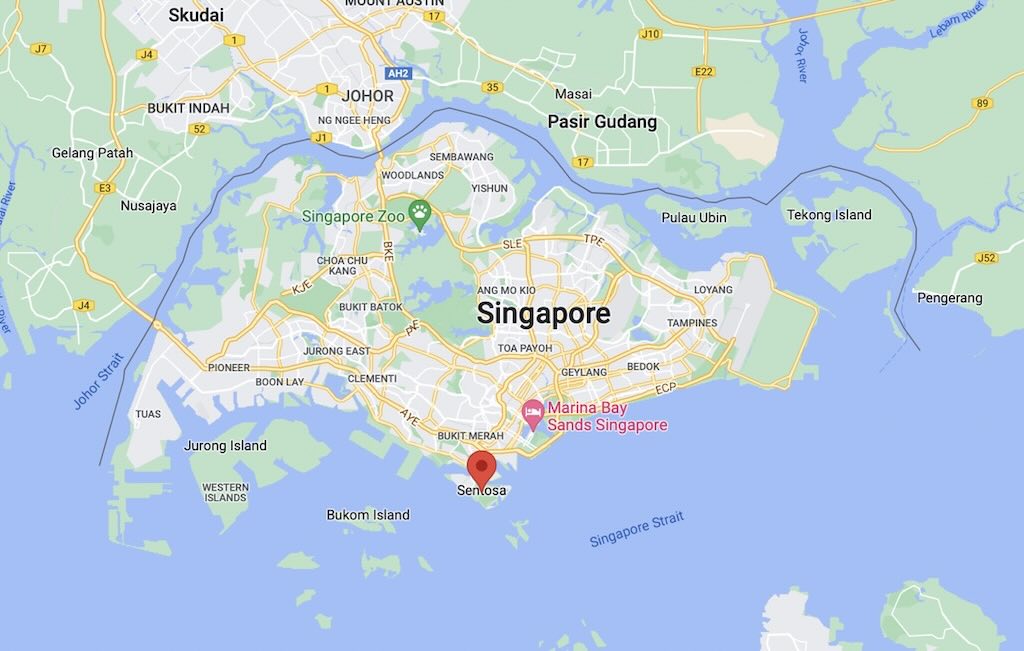

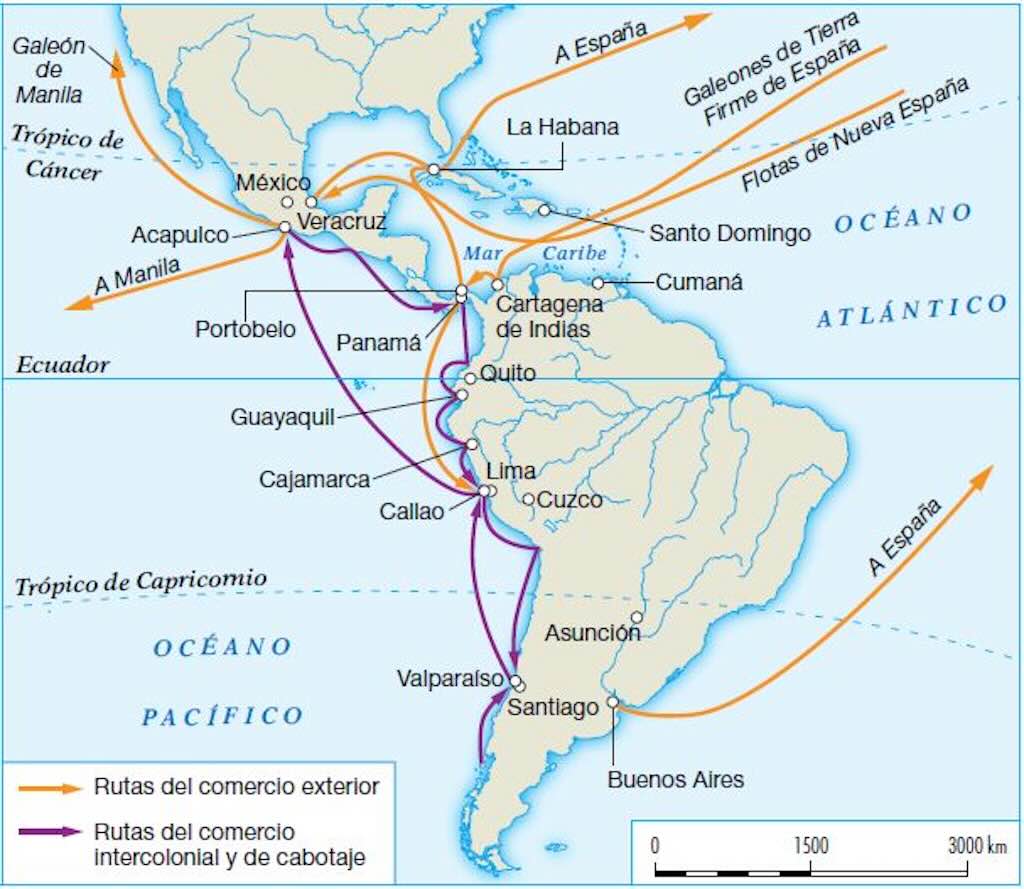

Overland from Potosí to Buenos Aires

- Silver extracted from Potosí was first carried across the Andes by caravans of 10,000-15,000 mules and llamas.

- The silver travelled to Salta and Tucumán, passing through modern-day Bolivia and northern Argentina.

- From there, it continued southeast via Córdoba and then reached Buenos Aires, the main Atlantic port of the Río de la Plata region.

- Potosí to Buenos Aires (overland) ≈2,700 km, and took 3-4 months.

Shipment from Buenos Aires to Spain

- Silver was loaded onto ships that sailed along the South American coast northward toward Brazil.

- Ships either sailed directly to Spain or made stops in Portuguese-controlled Salvador (Bahia) or Rio de Janeiro to resupply.

- From there, they crossed the Atlantic, often passing the Azores Islands, before reaching Cádiz or Seville.

- The ships themselves were usually medium-sized galleons (200-400 tons), and fleets were also smaller than the Caribbean treasure convoys (5-15 ships).

- A ship would carry between 2-8 tons of silver, in the form of bars, ingots, and coin.

- Convoys from Buenos Aires could leave twice a year, but departures were irregular.

- Silver quantities were less than through the Caribbean, but could still add up to 100s of tons per year.

- This trip was ≈10,000 km, and took 60–120 days, depending on weather conditions.

- The total trip from Potosí could take ≈6-12 months, so potentially a little longer than via Havana.

Via Cape Horn

- Some sources mention a southern route around Cape Horn to Buenos Aires.

- This would have been extremely dangerous, and I’ve found no data on its use in real life.

Risks and contraband trade

Initially the Buenos Aires route was less secure than the Caribbean route, making it more vulnerable to smugglers and illegal traders (especially British and Portuguese). The Portuguese in Brazil often facilitated silver smuggling via their colony, allowing silver to be traded illegally in Europe and Africa. British merchants also traded with Buenos Aires, despite Spanish efforts to control commerce.

Initially, the Spanish Crown preferred the Lima–Panama–Havana route because it was easier to control. However, by the late 17th and 18th centuries, the Buenos Aires route became officially sanctioned, as Spain tried to reinforce its presence in the region. In 1776, Spain created the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, which gave Buenos Aires more commercial power and legitimised silver shipments via the Atlantic.

We have to remember that before the Bourbon Reforms Spain restricted direct trade from Buenos Aires to Spain, forcing silver to go via Lima and Panama. The reforms allowed Buenos Aires to legally export silver, and the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata made Buenos Aires an administrative centre for silver trade.

Piracy and wars in and around the Caribbean often made the route through Havana more dangerous, so shipping silver thought Buenos Aires might have been slower, but sometimes it was a safer option.

This silver shipments remained the backbone of the Spanish Empire’s wealth until the early 19th century, when revolutions and British naval dominance broke Spanish control over the silver trade.

Buenos Aires and the Silver Trade (official & smuggling) in the 17th Century

Buenos Aires was a relatively small and remote outpost of the Spanish Empire in the 17th century, but it would play an increasingly important role in both the official and contraband silver trade. Due to strict Spanish mercantile policies, the Buenos Aires’s economic survival often depended on illicit trade.

The Spanish commercial system & Buenos Aires’ position

- Spain controlled its American trade through a monopoly system, with all legal silver shipments required to pass through the Viceroyalty of Peru (Lima) and the Casa de Contratación in Seville, via the Spanish Treasure Fleet.

- Buenos Aires was part of the Viceroyalty of Peru but was marginalised in this system, as trade was meant to flow through Lima and then via Panama to Spain.

- Officially, Buenos Aires was meant to be a minor port that exported local goods like hides and imported basic supplies.

The Camino Real and silver flow

- Silver from Potosí travelled primarily westward to Lima, where it was shipped to Spain.

- However, some silver was transported eastward overland to Buenos Aires, via Córdoba and Santa Fe, as part of a secondary trade route.

Buenos Aires became a smuggling hub

- Spain’s monopoly on trade forced Buenos Aires into an economic crisis, as legal commerce was severely restricted.

- Since it was much cheaper and faster to send silver eastward from Potosí to Buenos Aires than westward to Lima, smugglers exploited this alternative route.

- Instead of following the official route westward to Lima, silver was illegally transported eastward by mule caravans across present-day Bolivia and Argentina to Buenos Aires.

- The contraband silver was smuggled via ships leaving Buenos Aires.

- The primary recipients of smuggled silver were Portuguese traders in Colônia do Sacramento (across the Río de la Plata in present-day Uruguay), Dutch & English merchants, who operated illegal trade networks, and Brazil, where Portuguese traders funnelled silver into the Atlantic trade system.

Scale of smuggling

- It is estimated that a third or more of Potosí’s silver may have avoided official Spanish taxation by travelling east instead of west.

- By some accounts, millions of pesos worth of silver illegally passed through Buenos Aires annually.

- Buenos Aires, despite its small size, became a major hub for pirate and contraband silver trade, indirectly linking South America to global markets.

- The Spanish crown’s officials in Buenos Aires were often underpaid and corrupt, leading many to turn a blind eye to smuggling in exchange for bribes.

- Local merchants, lacking access to legal Spanish imports, depended on contraband silver to purchase goods from foreign traders.

Impact of smuggling on Buenos Aires

- Economic Growth: While officially ignored, silver smuggling enriched Buenos Aires, allowing it to grow beyond its role as a minor outpost.

- Conflict with Lima & Madrid: Smuggling weakened Peru’s economy and reduced royal tax revenue, leading to periodic crackdowns from Spanish authorities.

- Foundation for Future Autonomy: The city’s strong ties to illegal trade and financial independence laid the groundwork for Buenos Aires’ later push for autonomy, culminating in the Argentine independence movement in the 19th century.

Buenos Aires’ role in the silver trade was far greater in smuggling than in official commerce. While legally sidelined by Spain’s mercantile policies, its strategic location made it a major conduit for illegal silver flows from Potosí to Europe and Asia. Over time, this smuggling activity enriched the local economy, connected it to global markets, and contributed to its growing independence from Lima and Madrid.

Estimated quantities and value

Alexander von Humboldt, a prominent naturalist and explorer, estimated in the late 18th century that precious metals lost to contraband represented approximately 17-20% of the total volume ever mined. If we consider that the Spanish treasure fleet legally transported an average of 9 million pesos per year in silver during the 17th century, a 17-20% contraband rate would imply that approximately 1.5 to 1.8 million pesos’ worth of silver were smuggled annually.

In today’s terms, considering that one peso contained approximately 27 grams of silver, the total annual smuggled silver would be around 38 to 45 metric tons. With current silver prices at approximately $33.20 per ounce (as of March 12, 2025), and considering there are about 32.15 troy ounces in a kilogram, the modern value of the smuggled silver would be approximately $40 to $50 million annually.

$40 to $50 million does not appear much by todays standard. However, in the 17th century, silver had vastly greater purchasing power due to its role as the global currency.

What could silver coin buy in the 17th century?

With one peso (~27g of silver):

- A basic workhorse or mule might cost around 20-30 pesos

- A tiny, marginal plot (uncultivated or difficult terrain) might cost 1-3 pesos

- Fertile or irrigated land could cost 5–50 pesos

- A little more than 1 pesos was a weekly wage for skilled labourer’s (carpenters, masons, etc.)

- 50 litres of wine bought bulk in a local market

- 100 kilograms of wheat (average harvest)

- A musket could cost 8–12 pesos, depending on region and quality.

Annual official silver trade (9 million pesos) could buy:

- 300+ fully equipped warships for the Spanish navy

- Quarter-to-half of Spain’s entire military budget, depending upon wars, conflicts, etc.

- Enough food to sustain 1 million people for a year (subsistence levels).

Clearly, the official silver trade alone was enough to finance empires, armies, and global commerce.

The role of smuggled silver

Smuggled silver accounted for 1.5-1.8 million pesos annually (based on the conservative 17-20% estimate). That might not seem much compared to official trade, but it bypassed Spanish taxation and control, enriching individuals and foreign powers.

Where did smuggled silver go?

In Europe the silver funded wars & trade

- Dutch & English traders used it to:

- Fund wars against Spain (e.g. the Eighty Years’ War).

- Finance the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and British East India Company.

- Expand Atlantic trade, including the slave trade.

In Asia it fed the Chinese silver market

- China had a high demand for silver because:

In Brazil & Portugal the silver financed sugar and gold

- Smugglers exchanged silver in Brazil for:

- African slaves, needed for plantations in the Caribbean & Brazil.

- Portuguese goods illegally brought into Spanish territories.

- Financing Portugal’s gold rush in the late 1600s.

And in the Río de la Plata it produced a local wealth boom

- Buenos Aires elites hoarded silver, built estancias (large ranches), and controlled trade networks.

- Created an early economic elite, laying the foundation for Argentina’s later independence movement.

Even though smuggled silver was “only” $40-50 million annually in modern terms, in the 17th century, that was enough to equip armies, fund conflicts, and influence global trade.

The Role of Buenos Aires in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Buenos Aires’ role in the transatlantic slave trade was far from peripheral. As a key node in the Spanish Empire’s economic system, the city facilitated both the legal and illicit movement of enslaved Africans, linking human trafficking to silver smuggling and contraband trade. While not as prominent as other ports in the Americas, Buenos Aires served as a crucial entry point for African slaves into the Río de la Plata region, functioning as both a legal and illicit trading hub. The city’s involvement in human trafficking was intricately tied to its economic reliance on silver, the commercial networks of the Spanish Empire, and widespread smuggling operations.

The evolution of slave trading in Buenos Aires

The first recorded African slaves arrived in the Río de la Plata region in 1588. Spain’s mercantile policies limited direct trade with Buenos Aires, forcing local elites to seek alternative sources of labour, including illicit slave trafficking. The Crown initially attempted to regulate this trade through the Asiento system, contracts awarded to foreign merchants to supply enslaved Africans to Spanish territories. Notably, the British South Sea Company gained control of the Asiento in 1713, intensifying the influx of slaves into Buenos Aires.

Between 1714 and 1739, the South Sea Company transported approximately 34,000 enslaved Africans to Spanish America, with Buenos Aires serving as a redistribution center. The mortality rate during transatlantic voyages ranged between 10-15%, with additional losses occurring during inland transport and forced labour assignments. For instance, the Prince, a British slave ship, arrived in Buenos Aires in 1788 with 355 slaves, having lost 17% of its human cargo during the journey from Bonny, West Africa.

Origins of the enslaved population

The majority of enslaved Africans arriving in Buenos Aires originated from West and Central Africa, primarily from present-day Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the Congo. The Portuguese controlled much of this trade, using their colonies in Angola as key supply points. Unlike the influx of Yoruba and Ewe ethnic groups into Brazil, Argentina received a higher proportion of Bantu-speaking Africans.

Upon arrival, enslaved individuals were auctioned in Buenos Aires and then transported to interior regions such as Córdoba, Mendoza, and Tucumán, where they worked in agriculture, domestic service, and artisanal trades. The 1778 census provides a striking picture of the demographic impact of this forced migration, where Afro-descendants composed over 50% of the population in some provinces. This demonstrates how slavery permeated regional economies far beyond Buenos Aires itself.

The nexus between slave trade, silver, and smuggling

Buenos Aires’ slave trade cannot be separated from its role in the global silver economy. Officially, Spanish colonial trade was highly regulated, with silver from Potosí (in modern-day Bolivia) required to pass through Lima before reaching Spain. However, Buenos Aires emerged as a significant center for the contraband silver trade, circumventing official routes and allowing local merchants to profit from illicit exchanges with Portuguese, British, and Dutch traders.

The demand for labour in silver mines and urban economies fueled the demand for enslaved Africans. At the same time, European merchants sought to acquire silver outside of the heavily taxed Spanish commercial system. Buenos Aires became a vital link in these underground networks, functioning as both an entry point for enslaved Africans and a conduit for smuggled silver destined for Europe and the Atlantic economy. The interdependence between slave labour and silver smuggling highlights the degree to which Buenos Aires operated outside formal Spanish economic controls, reinforcing its role as a semi-autonomous commercial center.

Mortality and living conditions

While specific records on death rates in Buenos Aires remain incomplete, maritime records suggest that 10-15% of captives perished during the Middle Passage. However, broader estimates including pre-embarkation and post-arrival conditions suggest that up to 40% of Africans intended for sale in the Americas died before reaching their final destinations. Once in Buenos Aires, many enslaved individuals faced further hardships, with urban and rural labour conditions often leading to high mortality rates due to disease, malnutrition, and harsh treatment.

Urban slavery in Buenos Aires presented a different but equally brutal reality. Enslaved individuals worked in households, tanneries, and artisan trades, with some allowed to hire themselves out for wages, a practice that occasionally led to manumission. However, their legal and social status remained precarious, and by the late colonial period, a significant portion of Buenos Aires’ labour force was composed of enslaved or free Afro-descendants who still faced systemic discrimination.

The decline of the slave trade and legacy

The transatlantic slave trade to Buenos Aires gradually declined in the early 19th century, partly due to Spanish-American independence movements and shifting economic priorities. Argentina formally abolished slavery in 1813 with the Ley de la Libertad de Vientres, which granted freedom to children born to enslaved mothers, although full abolition did not occur until the mid-19th century. Despite this legal shift, Afro-Argentine communities continued to face systemic marginalization, and their historical contributions remain underrepresented in mainstream narratives.

By the 19th century, the Afro-Argentine population had declined significantly due to forced military conscription, high mortality rates, and social policies aimed at erasing African heritage. This demographic shift, coupled with waves of European immigration, led to the misconception that Argentina was a country with little African influence.

Buenos Aires - from Colonial Port to Cosmopolitan Capital

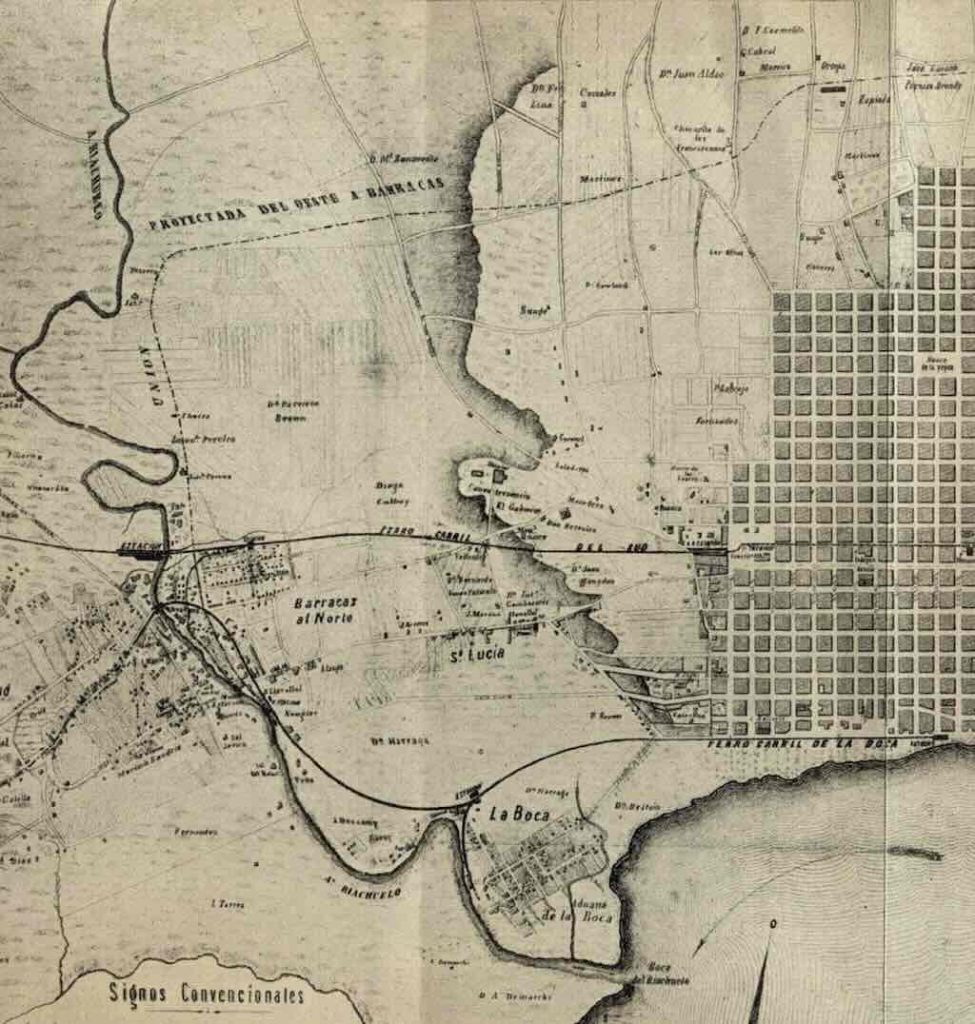

It is known that the streets of Buenos Aires did not begin to be paved until the end of the 18th century. And at the same time accessing the channel leading to the Riachuelo was increasingly difficult due in part to its narrowness, and in part the need to wait for the high tide and right wind. Yet, throughout the 18th century most of the river trade of Buenos Aires was concentrated in the port of the Riachuelo.

Technically the Riachuelo was outside the boundaries of Buenos Aires, but in practice it gradually came to define part of the perimeter of the city. So it’s no surprise that when the definitive limits of Buenos Aires were established, the Riachuelo was taken as a natural division between the city and the province.

The area of La Matanza began to be inhabited by some cattlemen and farmers at the beginning of the 17th century, and through the 18th century its populated grew more and more rapidly. In practice, La Matanza area became a true suburb of Buenos Aires. Today La Matanza is a partido (department) in the Buenos Aires Province, forming part of the Greater Buenos Aires metropolitan area. It is the most populous partido in Argentina, with over 1.8 million inhabitants, making it one of the largest urban areas outside the capital. It represents Buenos Aires, and Argentina, in that it has some middle-class areas and is a major industrial hub, yet it is also home to La Salada, one of Latin America’s largest informal markets (located today in Ingeniero Budge, Lomas de Zamora), and extensive working-class neighbourhoods including informal settlements (villas miseria).

The name “La Matanza” means “The Slaughter”, possibly referring to a 16th-century massacre of indigenous people by Spanish forces. And today it’s often called “the mother of all battles” in Argentine elections due to its massive voter base.

It’s obvious that the “barracas” were already being built at beginning of the 17th century, and they are mentioned throughout the 18th century. In Spanish barraca means hut, shack, or barrack (a place to live in). Historically, it referred to simple wooden or metal structures used for housing soldiers, workers, or storing goods. In some contexts, barracas also meant warehouses or riverside storage facilities for commercial goods. In Buenos Aires Barracas is a traditional neighbourhood (barrio) in Buenos Aires, south of the city centre. Originally a working-class area linked to immigrants (especially Spanish and Italian), it was known for its tanneries, textile factories, and warehouses. Already in 1719, the governor ordered that people “continúen y fenezcan el hacer los cueros que a cada uno se les repartió y los entreguen en las barracas a la persona que su señoría señalare” (continue and finish making the leather that was distributed to each one and deliver them in the barracas to the person that his Lordship designates).

The reason its mentioned here is that Las Barracas took on an increased importance when in 1785-86 the “boquete” (hole) opening in the Riachuelo coast, forming a new mouth and blocking the old channel access. Already in 1788 we learn that “the bustle of the ships and boats that navigate in the Riachuelo” was now located in “the place called Las Barracas“.

From a map of 1805, it showed two roads leading to Las Barracas (the map shown above dates from 1866 and also shows the rail links). At a discrete distance from these roads was the “la vuelta de Rocha” (Rocha bend or turn), a name that began to appear at the end of the 19th century. This area was completely uninhabited. The land was exposed to continuous flooding, and it was very difficult to build houses and a stable settlement. The ships sailed past until they could reach the “dry” land, where Las Barracas began.

This is the place which later would become La Boca.

Despite being a difficult area a few ‘grocery stores’ were established and some shacks and cabins for the inhabitants were also built. In 1836 a famous painter, C. E.Pellegrini, painted “El puerto de los tachos“, the name given at that time to the Rocha bend. A ship is seen at anchor, and on the low and narrow banks to the left there is a primitive peña hut. A peña is a rural or traditional shelters in the countryside, possibly a simple stone or wood hut used by shepherds. Another painting by Pellegrini showed the same place from another point of view. In it there are seven huts, a ship and a dock.

The first settlers on the banks of the Riachuelo were the owners of the land. Early maps bear the name of Riachuelo de Barracas, and the Río de la Plata also bore the name of “great Paraná“. The lands on the left bank, were marked as “Barracas lands”, which at the time extended equally from the coast of the Río de la Plata to “the land of the Abellanedas” a huge expanse on both banks of the Riachuelo that would become Avellaneda.

The history of the first settlers of La Boca is lost, possibly it was never truly known. They were families who lived in small wooden houses, of two or three rooms, “held high by strong piles firmly secured in the ground”. Often the piles would remain, but the houses were transported on carts from one place to another. The Riachuelo did not have the embankments to prevent the continuous flooding. These floods were very frequent, as reported in a travel book from the mid-19th century, “All the houses had the indispensable canoe tied to one of the piles by a strong chain rope. It was a very light, flat-bottomed boat, because at that time the Boca flooded at every moment and the inhabitants, sometimes to travel through the streets that had become canals, or to get to safety when the flooding was terrible, used their little boats”.

When the waters did not rise too much, it was common to see a woman or a child go in a canoe to the store or the butcher shop. When the waters rose, they could enter the city, and on at least one occasion the Plaza de la Victoria (today’s Plaza de Mayo) was flooded.

At the Rocha bend, it is known that Admiral Brown prepared the squadron with which he had so many successes.

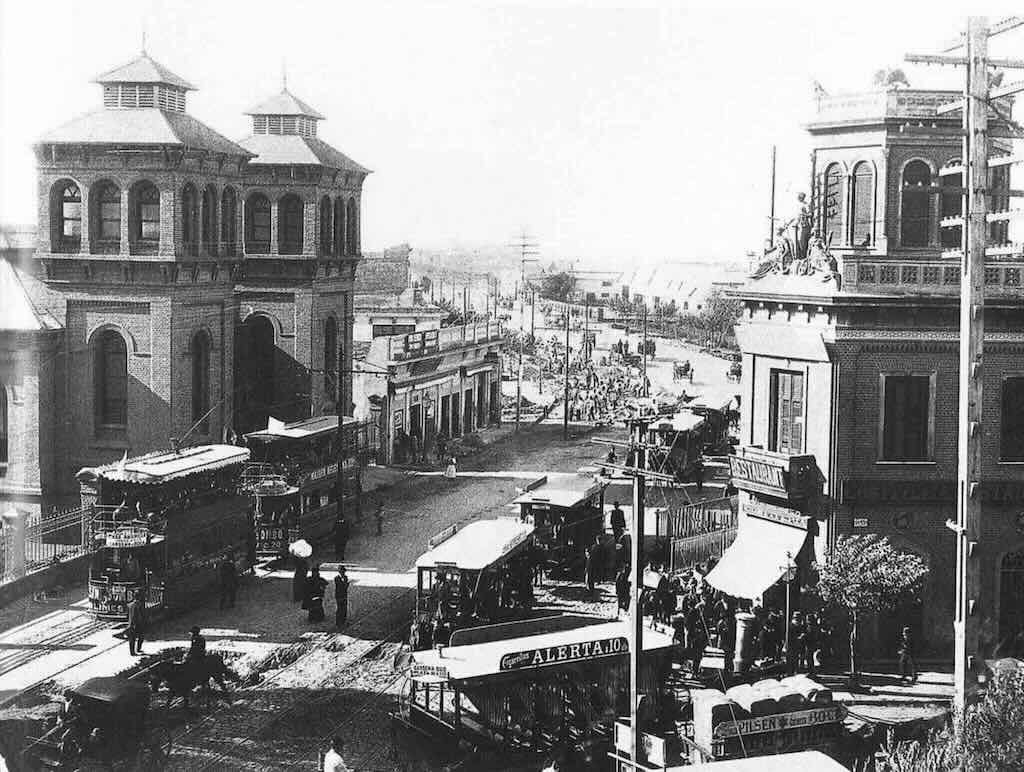

The area around the mouth of the Riachuelo began to develop around that time and still today it can be considered as one of the most densely populated neighbourhoods of the capital. In 1868, when the Argentine nation was emerging, the Boca neighbourhood was described as…

“The banks are populated with warehouses, workshops and salting houses, where all the country’s export products are prepared for shipment, wool, leather, tallow, etc. There is also no lack of taverns and all kinds of establishments related to seafarers. This represents a maritime neighbourhood of importance… There has been a project for many years, to convert the Riachuelo into a true port, channeling it to admit all kinds of ships, and embanking its swampy banks, in order to convert them into beautiful and comfortable docks… however the vicissitudes that this beautiful country has gone through and is still going through, will not allow his government to carry out this great project”.

However in 1881, Eduardo Madero began the construction of the great port of Buenos Aires. The work was directed by the engineers Thomas A. Walker, James Murray Dobson, Joseph Talbot and John Hawkshaw. The meander of the Rocha bend was cut to make way for a comfortable anchorage. Where the northern channel of the Riachuelo had previously run, the dikes were excavated, and the mouth of the “Trajinista” was cleared and opened.

La Boca - Buenos Aires’ First Gateway to the World

The development of the port in La Boca, Buenos Aires, played a pivotal role in Argentina’s economic expansion during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Design and construction

In the late 19th century, Buenos Aires faced significant challenges with its existing port facilities, which were inadequate for the increasing maritime traffic. To address this, the government sought proposals for modernizing the port infrastructure.

Luis Augusto Huergo, Argentina’s first civil engineer, proposed an ambitious plan to develop a new port in the La Boca area. His design included constructing a breakwater and dredging the Riachuelo river’s mouth to a depth of 6.5 meters to accommodate larger vessels. The port’s opening in 1880 coincided with a sudden economic boom in Argentina. The Provincial Legislature awarded him a generous budget for improvements, including a breakwater and the dredging of the silty Riachuelo mouth to 6.5 metres.

Completion and costs

The port’s initial phase was completed and inaugurated in 1880. While specific financial details from that period are scarce, it’s documented that the Provincial Legislature allocated a substantial budget for the project’s completion. Huergo’s design focused on creating a functional and efficient port to boost the nation’s trade capabilities.

Ships and goods in La Boca port

Due to the shallow depth of the Riachuelo, La Boca’s port primarily accommodated small ships. The mouth of the Riachuelo has always been the natural port of Buenos Aires, but allowed only small ships to anchor due to its limited depth. This limitation meant that larger vessels had to anchor offshore, with passengers and cargo transferred via smaller boats to the port. The port primarily handled goods such as meat, dairy products, wool, leather, grain, and tobacco, reflecting Argentina’s agricultural and livestock production during that era.

Evolution over time

Following its inauguration, the Port of La Boca underwent several transformations:

Puente Transbordador: In 1914, the transporter bridge was inaugurated, connecting Buenos Aires with the outskirts across the Riachuelo. This bridge facilitated the movement of pedestrians, carts, cars, and trams, enhancing connectivity in the port area.

Puerto Madero Development: By the late 19th century, the limitations of the existing port facilities led to the development of Puerto Madero. However, as shipping technology evolved, Puerto Madero’s docks became obsolete, prompting the construction of a new port north of the original facilities. This new port, based on Huergo’s earlier designs, addressed the growing demands of maritime trade.

Relationship with Puerto Madero

Puerto Madero was developed as a modern port facility to address the inadequacies of existing ports like La Boca. Inaugurated in 1897, Puerto Madero featured docks designed to accommodate larger ships. However, due to rapid advancements in shipping technology and the increasing size of vessels, Puerto Madero’s docks became obsolete within a few decades. This obsolescence led to the development of a new port, Puerto Nuevo, which continues to serve as Buenos Aires’ main port today.

Goods handled at Puerto Madero

Puerto Madero included warehouses for imported goods and silos for grain destined for export. The docks were equipped with facilities to handle various cargo types, reflecting the diverse trade activities of Buenos Aires during that period.

Differences between the original and contemporary Puerto Madero

Original Puerto Madero (Late 19th to Early 20th Century): Designed by British engineer Sir John Hawkshaw and inaugurated in 1897, the original Puerto Madero consisted of a series of docks intended to modernize Buenos Aires’ port facilities. Despite being an engineering achievement of its time, the port became obsolete within a decade due to the increasing size of ships, leading to its gradual abandonment.

Contemporary Puerto Madero (Late 20th Century to Present): Starting in the 1990s, Puerto Madero underwent a significant transformation from a derelict port area to one of Buenos Aires’ most upscale neighborhoods. The revitalization involved converting old warehouses into lofts, offices, restaurants, and cultural spaces. The area now features modern high-rise buildings, luxurious hotels, and extensive parks, making it a prime example of successful urban redevelopment.

We will return later to visit the modern Puerto Madero.

Las Cantinas in La Boca

Most visitors to Buenos Aires, and in particular to La Boca, will mention the Tango, Caminito, and Boca Juniors as “cultural institutions”.

I want to focus on a different, but equally important institution, La Cantina.

The institution of the cantina in Buenos Aires, particularly in the La Boca neighbourhood, is deeply intertwined with the area’s rich history of Italian immigration and its working-class roots.

Originating in Italy but adopted in La Boca

The Italian immigrants who settled in Buenos Aires in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many from Genoa, adapted to their new surroundings, creating the cantinas of La Boca. These establishments served as communal gathering places where traditional Italian dishes were prepared and shared. The cantinas became integral to the social fabric of La Boca, offering familiar tastes and a sense of community to the immigrant population.

One of the most notable events in La Boca’s history occurred in 1882, when a group of Italian immigrants, led by Genoese activist Juan Bautista Caffarena, declared La Boca’s secession from Argentina, pledging allegiance to the Kingdom of Italy. The rebellion was short-lived, as then-President Julio Argentino Roca swiftly intervened, but it underscored the neighborhood’s strong Genoese identity.

Along with the cantina we also have the mensa, but what is the difference?

The original Italian word mensa comes directly from Latin mensa, which primarily meant table in ancient Rome, especially a table for meals, dining table, or meal itself by extension. Over time mensa came to mean canteen, refectory, or mess hall, so a place where meals were/are served, especially in institutions like schools, factories, barracks, or universities. In medieval texts mensa still carried the double meaning of both table and feast.

I’m not sure the word mensa ever found its way to Buenos Aires, but the concept certain did. The idea and function of communal eating linked to religious or charitable institutions did exist in early Buenos Aires, especially through the Church and religious orders. These were probably called refectorios (refectories) in convents and monasteries. We know that men (Jesuits, Franciscans, Mercedarians) and women (Clarissas, Dominicans) adopted organised communal dining following strict timetables (horario de mesa, etc.). The meals were simple, regulated, and spiritually framed, much like the mensa tradition in monastic Italy.

Hospitals and hospices often included communal dining rooms for the poor or sick. These were sometimes called comedores, but the model was inherited directly from Spanish and Italian Catholic practices, which were themselves heirs of the Roman mensa tradition.

In the inventories of the early Cabildo and religious orders of Buenos Aires, tables are sometimes referred to in old Spanish as mesa or mensa, reflecting this older Latin term surviving in official or ecclesiastical language. For example, some convent accounts or wills mention mensa conventualis or mensa de los pobres.

Unlike the mensa, which came from ecclesiastical or institutional contexts, the cantina is a much more popular, everyday, and even bohemian institution. In the 17th and 18th centuries there were pulperías, tabernas, and chicherías (chicha taverns) functioning more as taverns or general stores, sometimes offering a bite to eat and, crucially, drinks. These were ancestors or functional cousins to cantinas. They were social hubs where workers and sailors mixed with locals, trading goods and stories. There is little direct evidence that they were called cantinas yet, but the concept was there.

The cantina as such was imported more explicitly with the arrival of Italian immigrants. By mid-to-late 19th century, cantinas in Buenos Aires became working-class eateries combining simple meals, vino de la casa, and a social space with games (cards, dice), music, etc. In neighborhoods like La Boca, Barracas, and later San Telmo, cantinas were essential to the Italian-Argentine identity. In the 20th century they became part of the Buenos Aires mythos, family run with dim lighting, long wooden tables, homemade wine, and unpretentious food. You find cantinas referenced in tango lyrics, costumbrista literature, and oral tradition. The typical cantina porteña was a place where food and conversation mattered equally.

It’s interesting, that there are suggestions that the cantinas in the different barrios, were subtly different. In La Boca the cantinas were for dock workers and the dishes were Ligurian-porteño hybrids, e.g. calamares a la provenzal, fainá, pasta con tuco, buñuelos, cheap and abundant. In Barracas, the neighbourhood was dominated by meat processing (saladeros) and railway industries, and the cantinas were more rustic, and served guisos, locros, and mondongo. Here the cantinas also served as places for union groups and political discussion, particularly with the rise of anarchist and socialist ideas among immigrant workers. In San Telmo, the cantinas served small artisans, musicians, and mixed families, so offering Spanish, Italian, and Criollo dishes. By the early 20th century, some cantinas even had small performance spaces (salones), hosting early tango musicians, poets, and payadores.

Present-day cantinas in La Boca

While many traditional cantinas have disappeared, some remain, preserving the old flavours and atmosphere. Notable cantinas still in operation include El Obrero, a beloved working-class institution serving classic Argentine and Italian dishes, Il Materello, known for its homemade pasta, and Don Carlos, located near the Boca Juniors stadium.

I didn’t mention tango, but…

In the late 19th century, the word tango in Buenos Aires did not yet refer to a fully formed dance, nor to a fully structured musical genre. Instead, it was a term of African and Afro-Argentine origin likely linked to tam-tam, meaning drum, gathering, or festivity. It is said to have derived from the milonga, an earlier sung form, itself a creole blend of payada (rural sung poetry) and African rhythms.

In the early arrabales (poor outskirts), tango was often first a storytelling verse, a romanza, often melancholic, ironic, or picaresque. And only later sung or recited in bars, conventillos, and in cantinas. Later still, as these milongas and early tangos were played by small ensembles (guitar, flute, violin), did they stabilise musically. The dance emerged gradually, not fully crystallised until about 1900-1910. Only around 1905-1910 in the Buenos Aires suburbs, and even more in Paris, did tango become the sensual, codified dance we now recognise.

As I returned to Spain for the winter 2024-25, some people suggested that there was a link between tango and flamenco and Andalusian folk dances (like fandangos, malagueñas, seguiriyas, soleares). My understanding is that they were certainly known in Buenos Aires through Spanish immigrants and touring performers. The dramatic gestures, sharp footwork, and passionate expressiveness of these dances (and music) did seep into the early development of tango, especially into the tango andaluz, an early form related to Spanish theatre (but culturally quite different. Also it is said that the Cuban habanera rhythm actually reached Buenos Aires largely via Spanish sailors and Spanish theatres. The habanera was foundational in the rhythmic structure of early tango. However, tango is more of a port city fusion which mixed almost every influence that arrived on its docks, e.g. Italian, African, Afro-Argentine (candombe, milonga), Italian canzonettas and even Eastern European folk melodies.

It is also true that the posture, intensity, and attitude you see in flamenco and tango have a kinship. Both are proud, confrontational, and intimate at the same time. And the theatricality and duende (flamenco’s emotional depth) are reflected in tango’s search for sentimiento (feeling).

But none of this should detract from tango’s cultural uniqueness.

Caminito - what was, what is...

Caminto que el tiempo ha borrado,

que juntos un día nos viste pasar,

he venido por última vez,

he venido a contarte mi mal.

Translation:

Little path that time has erased,

you who once saw us pass by together,

I’ve come for the last time,

I’ve come to tell you of my sorrow.

This is the first verse, and it is very famous among tango lovers. It sets the nostalgic and melancholy tone of the entire piece, where the narrator returns to a path (caminito) that once witnessed love, but now only serves as a silent witness to sorrow and loss.

The tango continues with similar heartfelt lines about absence, memory, and the passing of time, typical of tango canción of that period.

Here, caminito is more than just a physical place. It’s a witness to a past love, a symbol of memory and loss. The diminutive adds tenderness, as if the speaker is addressing an old friend. The tango became an anthem of Buenos Aires’ La Boca neighbourhood.

However, the reality is that the little side street was originally called “Puntín” a term derived from the Genoese dialect meaning “small bridge”. This name referred to a small bridge that once crossed a stream flowing into the Riachuelo along the path’s course. After the stream dried up, the little path was used for railway tracks until their removal in 1928.

The lyrics, penned by Gabino Coria Peñaloza, actually refer to a different “Caminito“. This one is located in the village of Olta, in the province of La Rioja, where Peñaloza had a romantic connection. In the 1950s, the street in La Boca had fallen into neglect. Local artist Benito Quinquela Martín led efforts to revitalize the area, transforming it into an open-air museum. In homage to his friend Filiberto and the tango that had brought fame to the name, Quinquela Martín named the street “Caminito“. So as a best guess the small side street got its name on October 18, 1959, the official inauguration of the street as an open-air museum.

There is an additional story, although I don’t know how true it is. The small side street was also once called “La Curva”, due to the shape of the section of rail laid in 1865. The track was used to transport freight between Garibaldi and Olavarría (stations that no longer exist) and the pier next to the Riachuelo. It was closed in 1928, and in 1954, when the tracks were removed, it was about to become a garbage dump. Apparently one night in front of the current corner someone dump a pile of spoiled cheese. Everyone smelt it. And it led the locals to put up posts to block the passage of trucks and cars, converting “La Curva” into an early pedestrian zone.

Above we can see the same building today. It is now a distinctive, brightly coloured building often adorned with life-sized figures of Argentine icons on its balcony. I think the building now houses souvenir shops and a café.

We can see Messi on the balcony. Previous occupants of the balcony, like Carlos Gardel, Diego Maradona, and Pope Francis, have been relegated to the side streets.

A Dialogue Between Puntín and Caminito, Like Two Old Friends

This is my little attempt at writing a dialogue between the past and the present in the form of a two-verse tango, with a refrain…

Puntín is the grey, useful, but silent, past, and Caminito is rebirth, vibrant, memory turned art.

Yo fui puente y sombra en la bruma,

de barriales y barcos sin ley,

y en mi lecho creciste, pintura,

con un color que no supe qué fue.

Ay, Puntín, viejo tronco del puerto,

tu recuerdo me anuda la voz,

pero yo, de tu barro despierto,

soy un canto que nunca murió.

Y en la ronda de viento y de tango,

entre el puerto, la pena y el sol,

somos huellas que el tiempo ha cruzado,

dos caminos trenzados.

Translation:

I was a bridge and shadow in the mist,

of mudflats and lawless ships,

and on my bed you grew, painted one,

with a colour I could never know.

Oh, Puntín, old trunk of the port,

your memory chokes my voice,

but I, awakened from your mud,

am a song that never died.

And in the round of wind and tango,

between the port, the sorrow, and sun,

we are traces the years have crossed,

two paths entwined.

Sorry for the Spanish, and the poorly versed translation.

Caminito - A Manufactured Attraction

It’s important to realise that the tourist spaces in the city centre largely overlaps with the daily life of residents. However, in La Boca, Caminito is just a tourist space (just restaurants, cafes, souvenir shops, etc.). All of these tourist-related spaces close at dusk, and the police are only present in the area during the opening hours.

I have thought long and hard about what I saw in La Boca, or more precisely, what Caiminito is.

Caminito is no longer a street. It’s a product. A narrow, colourful corridor designed to deliver a version of Buenos Aires that can be consumed quickly, photographed, and ticked off the must visit list. The original La Boca, working-class, immigrant, rough, has been reduced to decoration.

The dancers, the facades, the souvenir stalls, all play into the performance. It’s a loop. Tourists photograph other tourists, performers do what’s expected, everyone participates. It functions. It sells.

But this isn’t unique. Every big city has places like this. Former neighbourhoods turned into open-air stages. La Boca did what others have done. It packaged a version of itself before someone else tried and failed. If it hadn’t, it might’ve disappeared entirely.

And that’s the uncomfortable truth. Without Caminito as a product, La Boca might be dead, or buried under a building site. At least this way, some version remains. It’s thin, but visible.

I went once. Had an empanada, a beer, and left. I won’t go back. Why should I.

Nearby, the Monumento a Guillermo Brown stands almost unnoticed. There are no cameras, no tango, no tour guides pointing at it. It doesn’t sell. But it has more history than anything on that painted street.

Boca Juniors is still real. That stadium still has its heartbeat. That identity still breathes. But Caminito is different. It’s a simulation — Disney in Rags. The story plays out like one of their recycled plots – from nothing, to spectacle, to something that looks like poverty but is actually just set dressing. The rags are curated. The struggle is now aesthetic.

Would Benito Quinquela Martín be proud of what Caminito is now? Maybe. Maybe not. He wanted life, colour, pride. He didn’t want silence. But it’s not clear he would’ve wanted what La Boca has become — a neighbourhood preserved in form, but hollowed in purpose.

The tourists aren’t wrong. They come looking for something. But what they’re given is a version of La Boca that’s been polished, fenced off, and priced.

Caminito works. But it’s not alive.

Parque El Rosedal

So we drove to El Rosedal in Palermo. This is not just another city park. It is designed to be looked at, not just walked through.

The roses are the obvious draw. Over 18,000 of them, from more than a thousand varieties. Does anyone count them? The park was created in 1914, designed by agronomist Benito Javier Carrasco, under the influence of Carlos Thays, the man behind much of Buenos Aires’ public green space. The land it sits on once belonged to Juan Manuel de Rosas, until it was taken and turned into Parque Tres de Febrero after his fall.

I was drawn most to the lake and the ducks. Maybe it was the contrast, the calm water in a chaotic city. There’s also the Poet’s Garden, a series of busts arranged among the trees and beds, with names like Shakespeare, Dante, Borges. No plaques with poems, no quotes, just a quiet nod to past wordsmiths.

The Andalusian Patio, a gift from Seville in 1929, was quieter still. Tiled, shaded, almost easy to miss if you’re not looking. That’s part of the park’s character, it doesn’t advertise itself. It waits to be discovered.

What sets El Rosedal apart is that it doesn’t try to be wild or modern or trendy. It offers calm, structure, and space to slow down. I didn’t leave feeling amazed, but I left refreshed.

It’s also a garden of legends. There was talk of a mysterious rose thief in the 1930s and 1940s, who in the early morning, before the gates opened, would cut some roses. No one could catch the culprit. Whether true or not, to this day some park workers are said to leave a single rose near the Poets’ Garden as a nod to this story.

Then there are the gardeners who work there (called rosaleros) who have their own oral lore about which varieties “behave” and which are caprichosas (capricious). Some roses are said to “resist” transplantation or pruning unless treated with a special touch. The gardeners claim they can “feel” which bushes are sensitive.

Also before modern restrictions, El Rosedal was a popular meeting point for clandestine full-moon poetry readings, especially during the turbulent 1960s and 70s. Small groups would gather at night around the Poets’ Garden, reading works of banned authors or reciting improvised verses. It was considered both an act of cultural rebellion and a romantic gesture.

Finally, there is the story of the “sad rose”. There is one rose variety planted near the Patio Andaluz which never blooms properly. Gardeners have replaced it multiple times, but it keeps struggling. The story goes that the original plant was dedicated to a young woman who passed away shortly before her wedding, and that the rose “mourns” her loss. Gardeners today don’t give much credit to the story, but still, no one dares remove that spot from the garden design.

El Ateneo Grand Splendid

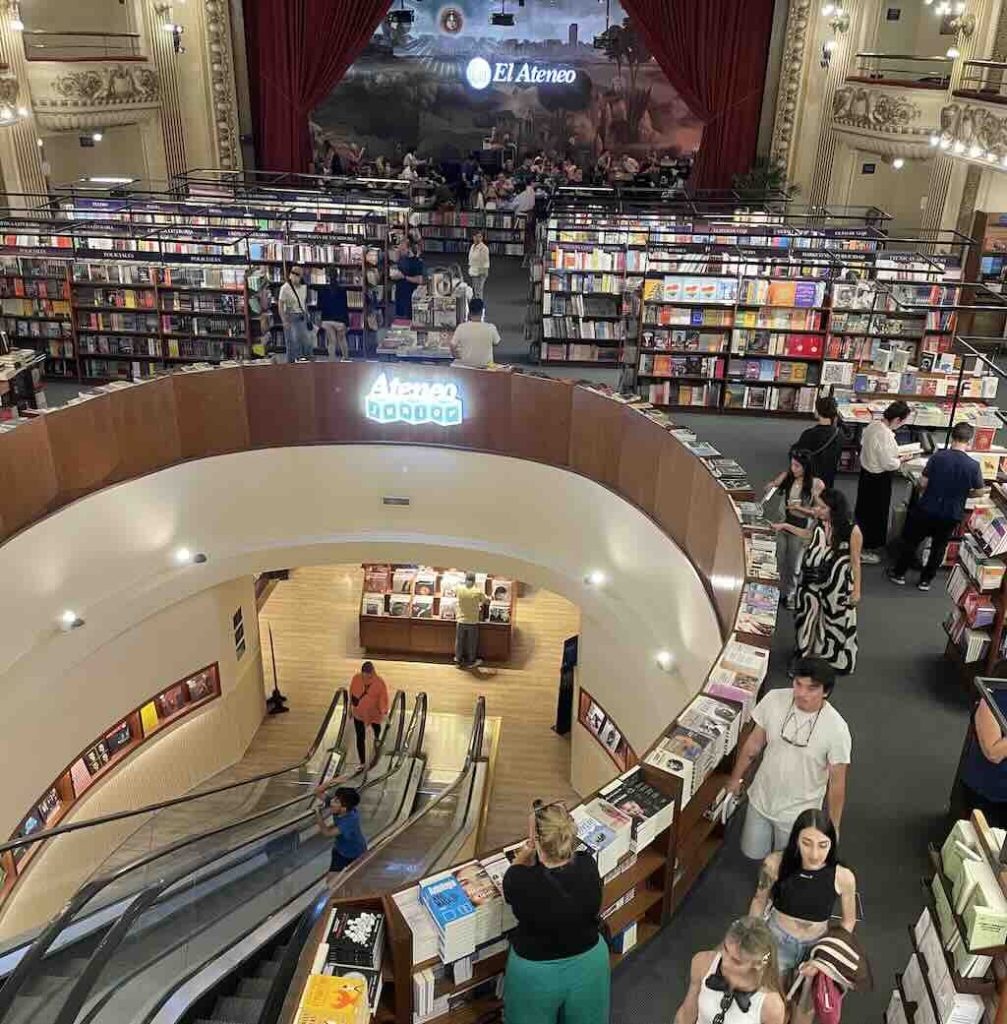

A short walk from my second hotel was El Ateneo Grand Splendid. It is the flagship bookstore of the El Ateneo chain, and is located at 1860 Avenida Santa Fe, in Buenos Aires. What unique about it is that it occupies approximately 2,000 square meters inside the former Teatro Grand Splendid, a theatre originally opened in 1919.

The theatre was originally commissioned by entrepreneur Max Glücksmann, a pioneer in the Argentine music and film industry, and designed by architects Peró and Torres Armengol. As a theatre it could seat more than 1,000 spectators and was a key venue for tango performances, theater plays, and later, early Argentine cinema.

After its conversion into a bookstore in 2000 the building still retains the original balconies, now filled with bookshelves. It still has the painted cupola (dome) by Italian artist Nazzareno Orlandi, and the red velvet stage curtains. Several original theatre boxes (palcos) are now intimate reading corners.

Today, El Ateneo Grand Splendid stocks around 120,000 books, receives around 1 million visitors per year, and sells about 700,000 books annually.

And the former stage is now a café, which overlooks the entire hall.

In 2019, National Geographic named it the “most beautiful bookstore in the world“, and it’s one of the top non-museum attractions in the city.

San Telmo Market

Another place I visited, with my guide Carlos, was the San Telmo Market. It was inaugurated in 1897, acceding to the designs of Juan Antonio Buschiazzo. The market preserves its original cast iron skeleton and about 5,000 square-meters of glass, typical of European-inspired markets of the time.

It is a public market with about 180 to 200 active stalls selling everything, from meat, fish, fruit & vegetable stalls, etc, through to antiques and collectibles, old books, vinyl records, etc.

In addition it hosts about 20+ food stalls and small restaurants. It has maybe around 10,000 visitors a day, probably more on weekends.

I took 2 empanadas and a local tap beer, costing around €8. This might be a little high, and we ate in “the best” casa de empanadas in the market. You can certain find lower prices elsewhere, but then you are not eating in the San Telmo market.

The History of Puerto Madero

The reality is that the need for a port structure dates back to the founding of the city. In fact Juan de Garay reserved a strip for port services opposite the site designated as the city’s fortress. But it would another 300 years before a port would be built at that location. During that time the banks of the Riachuelo had become an industrial zone. They were the seat of the shipping industry, the location of the first shipyards, and home to the meat packing industry.

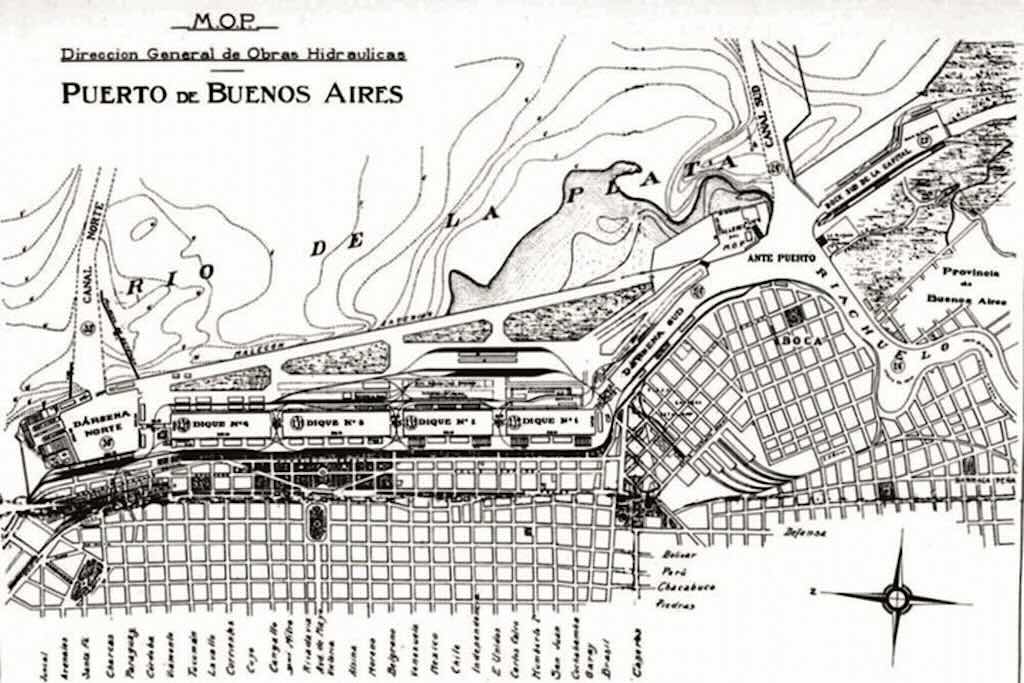

There were numerous plans for the waterfront, but most were never started until the end of the 19th century, with the inauguration of the old Puerto Madero in 1889. As early as 1771, a certain Francisco Rodríguez y Cerdoso planned a large rectangular basin. In 1782 and 1784, two more port projects were presented. In 1802, work began on the so-called Cerviño project, which called for the construction of a docking pier and a coastal canal connecting the pier to the Riachuelo. In 1805 another project consisting of a large canal parallel to the coast, along whose shores docks would be built, along with defensive structures and a coastal road on an embankment to prevent flooding. After the declaration of independence in 1816, several other projects were promoted, but they also failed to materialise. Finally, when the agricultural exports to Europe became important, Luis Huergo won the 1879 competition for a Riachuelo canalisation project. And there quickly emerged a dispute between the Huergo project and the Madero project.

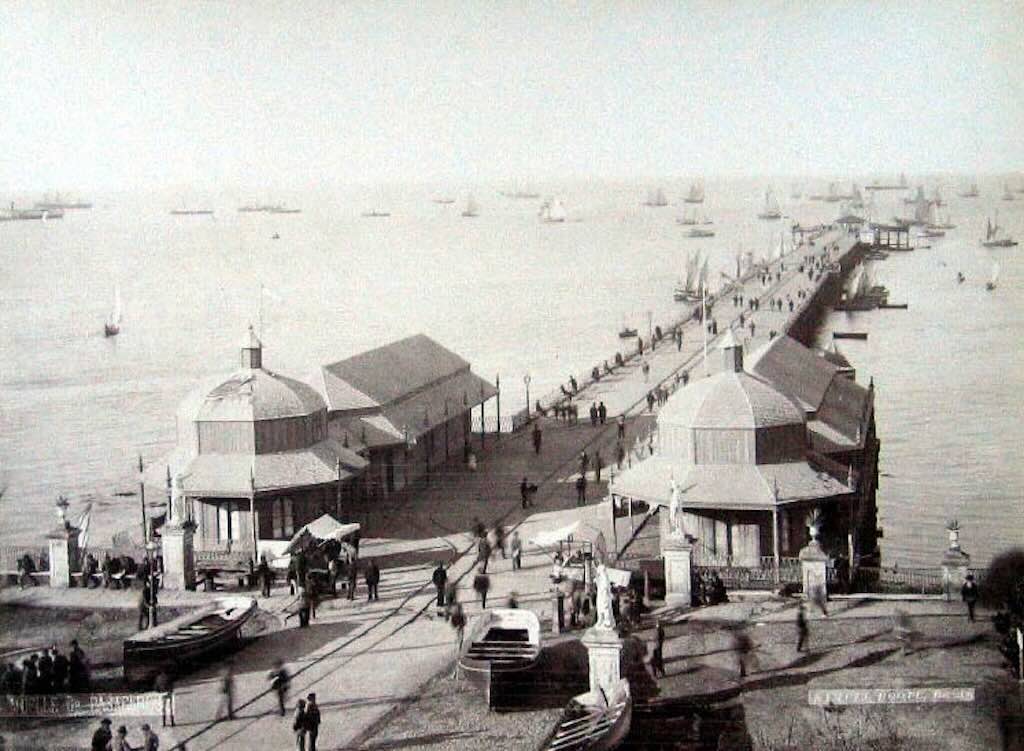

However, already in the 1840s Edward Taylor, a British merchant and entrepreneur, was commissioned by the Buenos Aires government to construct what became the first proper pier of the city, known as Muelle de Taylor (see the below photo). Construction started in 1845 and was completed around 1855. At the time, Buenos Aires suffered from a significant logistical problem, namely, that the Río de la Plata has a shallow and muddy shoreline, preventing large ships from docking directly at the coast. Passengers and cargo had to be transferred by small boats (lanchas) through a dangerous and inefficient process known as “transbordo en rada” (offshore transfer).

Taylor’s Pier was intended to partially solve this problem by extending into the river to allow medium-sized ships to dock more directly. However, due to the persistent problem of sedimentation and limited length (about 350 meters), it only marginally improved the situation. Still, it became the main docking structure for decades and was the central logistical hub of Buenos Aires during the mid-19th century.

Huergo’s proposal aimed at normal access for overseas vessels in to the Riachuelo. The aim was improving existing facilities by constructing indented basins open to the Río de la Plata. On the other hand, Madero’s project focused on the development of new infrastructure on the low-lying shores east of Plaza de Mayo. He proposed the construction of two access basins and four closed intermediate breakwaters, constructing an artificial island, and ignored the possibilities offered by the Riachuelo. Madero’s plan was wet docks enclosed by docks and locks, common in Britain, and specifically influenced by London (Royal Victoria Dock) and Liverpool.

Finally it was decided to go ahead with Madero’s proposal, and construction work started in 1887. Construction was contracted to the British firm Walker & Co. with engineering assistance from Sir John Hawkshaw. The project’s financing was secured via a British loan.

However, Puerto Madero did not constitute a technical innovation, nor did it manage to accommodate large vessels. About ten years after its completion, due to the increase in vessel size, Puerto Madero had become completely obsolete.

The construction of a new port was not long in coming. This time, following Huergo’s ideas, a series of open, comb-shaped basins was built. Puerto Nuevo was inaugurated in 1919.

In the above photo we can see Puerto Nuevo. The runway is not the Aeroparque Internacional Jorge Newbery, but the original Aeródromo de Palermo. It was the first organised aviation facility in Buenos Aires, and was established in 1910 to coincide with the Centenario de la Revolución de Mayo. Originally with a grass runway, it was paved in the late 1920s, but it was decommissioned between 1932 and 1934, and by 1940 it had fully disappeared. The land became part of the Parque Tres de Febrero expansion, and later parts of it were used for the Jardín Japonés, and the Planetario Galileo Galilei.

But as the decades passed, “the semi-abandoned facilities of Puerto Madero […] formed a barrier that had to be crossed to access the Costanera Sur, and this difficultly was compounded by the limited public transportation available to the area. Despite the difficulties in accessing it, the water pollution, and the ban on swimming, the Costanera Sur, with its beach resort and sports complex, remained a very popular and crowded public space until early 1976, when the military dictatorship began”. Between its inauguration and the late 1970s, the Costanera Sur began to decline, its restaurants and breweries closing. By 1979, the sports complex had fallen into disuse, and with it, the Costanera Sur. The whole area was hidden behind the 15,000 square-metres of rubble dumped during the building of a new highway network.

The reality is that Buenos Aires pushed its industrial activities and the settlement of the working population to the Riachuelo. They used the water and discharged their waste. They built bridges and the railroad in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which allowed the towns of Avellaneda (originally called Barracas al sur) and Quilmes to grow. In addition the Buenos Aires authorities located the municipal slaughterhouse in Parque Patricios and discharging untreated water in Nueva Pompeya. It is not surprising that “black belts” began to form, meaning housing without water, sewage, or lighting services, in flood-prone areas, and surrounded by garbage dumps. The topography of the area (flood-prone due to its marshland), the predominantly industrial land use, and the development of multiple (and precarious) forms of popular housing kept the southern bank safe from real estate speculation. Years later (beginning in the 1950s), another brake on speculation was imposed by the decision of the municipal authorities to locate significant social housing in the area.

This was the fate of the Riachuelo, dumping of industrial waste, a lack of urban infrastructure, landfills, and a population settled in undeveloped and flood-prone areas. Inevitably this resulted in the contamination of water and groundwater in the basin. This ‘snapshot’ of the southern bank remained more or less unchanged until the late 1980s, when the area’s transformation began.

The Military Dictatorship (1976-1983) did intervene with a new urban highway network, and the eradication of shantytowns. They changed the Building Code, proposed the construction of a park system, banned garbage incineration and cattle slaughter in the city.

The old Puerto Madero became obsolete, the warehouses and loading cranes abandoned. The Riachuelo (La Boca and Barracas) were deeply affected by de-industrialisation. The closure of workshops, factories, and warehouses, freed up both a large amount of land, and buildings suitable for reuse and/or demolition.

The old port might have been obsolete, but the above photo from 1990 clearly demonstrates that it was still in use.

During the first years of democratic government (1983-1987), they failed to end the acute crisis in the manufacturing industry, nor improve the conditions of the working classes. However, the reduction in interest rates in the local financial market, the opening of credit lines for home purchases, and the incorporation into the real estate market of state-owned land and buildings (e.g. Puerto Madero) created a construction boom. More building permits granted, property and land sales prices evolved positively, and there was a proliferation of new residential real estate offerings, geared toward upper- and upper-middle-class sectors, in “high-rise condos”. This boom was interrupted between 1998 and 2001, years in which one of the deepest social, economic, and institutional crises Argentina experienced in the 20th century erupted. In this context, the average purchase price per square meter hit rock bottom (average $US 600 per square-metre). However, starting in 2002, the renewal of old Puerto Madero and the Southern Riverbank started. The transformations enabled the development of new commercial, service, and residential uses for high-income sectors. But at the same time there were companies and agents who made enormous profits speculating on urban land development. And the government did nothing to stop it.

With the floods from the southeastern winds that repeatedly hit the Costanera Sur, the abandoned landfills filled with sediment, and vegetation began to grow spontaneously, forming the current Costanera Sur Ecological Reserve. Since then, despite its ups and downs, the re-generation project has continued and currently appears to be enjoying a positive public opinion.

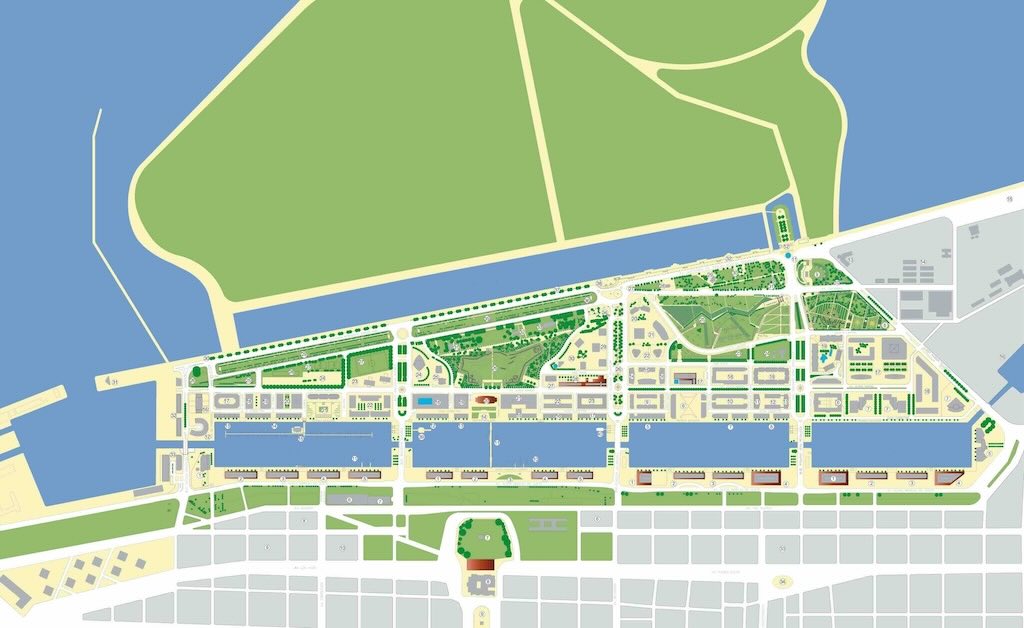

Puerto Madero Today

Above we have two photos of Puerto Madero, and it’s surrounding, dating from 1964 and 1998. In the 1964 photo what we see are earthen ridges (albardónes), originally created and filled-in when the docks were dug, and then built over. In the photo from 1998, again we can see some human reshaping, exploiting the continuing depositions of fluvial-marine sediments, which became grown-over naturally.

The Costanera Sur and the Reserva Ecológica stand today on reclaimed and filled land beyond the original albardón line.

So the barrio Puerto Madero, as seen above, is in many ways a relatively new area to the east of the city. We can see the Casa Rosata (in red) backs onto one of the series of four short docks (darsenas) separated by locks.

Experts have concluded that the revitalisation of Puerto Madero district has been both successful and unsuccessful. From an economic point of view, the intervention has been successful. What was an abandoned industrial area has become the most fashionable and expensive district of the city. It’s now open to residents and visitors who enjoy the promenade along the docks, parks, and coffee shops and restaurants. In many ways it has created a new relationship between the city and the river, something that was lost when Puerto Madero was originally constructed.

From a heritage point of view, Puerto Madero is an example of a partial preservation of architectural components and part of the remaining infrastructure, like the cranes, etc. However, in the eyes of the experts the redevelopment of the eastern bank makes the old warehouses, although properly preserved, appear a little anecdotal in a completely new district. Although Puerto Madero is considered an example of urban restructuring, pressure coming from real estate builder was (and still is) more powerful than the heritage vision. In the minds of those experts this may, or may not, prove expensive in the long-term.

The tourist visits…

I was with my excellent guide (Carlos carlopezbello@gmail.com). We had visited Plaza de Mayo, and went for a coffee in the renovated dock area Puerto Madero. Not the barrio, but the 21st century renovation of the old port area.

We took a quiet morning walk. This is not a place of leafy parks, but one of upscale waterfront restaurants, hotels and apartment blocks. But here and there, the old industrial bones of the city still show through.

It’s a curious blend, with the original historical warehouses, now repurposed, along with the old port cranes, all sitting alongside a striking display of 21st-century ambition.

The redevelopment involved repurposing historical warehouses into upscale offices, restaurants, and hotels, while also introducing modern residential and commercial structures. Notable developments include the residential El Faro Towers and Renoir Towers, and the corporate Repsol-YPF Tower. The area also features landmarks like the Puente de la Mujer, a pedestrian bridge designed by Santiago Calatrava.

As of recent data, property prices in Puerto Madero range from $6,000 to $10,000 per square meter, positioning it as the most expensive real estate in Argentina.

Future plans for Puerto Madero are “more of the same”, residential and commercial projects. Public opinion is mixed, with many locals appreciating the modernisation of the area. However, there are concerns about affordability and the area’s exclusivity. Many older residents have nostalgic sentiments for the port’s historical character, and think that it’s gone “too modern”.

There’s a certain calmness to the area. Perhaps a little over-curated, but not sterile. I liked the vibe, but I do think that putting up more nondescript office and residential buildings would be a mistake. They should really only accept iconic architecture from now on, and they should focus on more greening of the open spaces.

We found a terrace café near the water. But this is no longer a place of cargo and tides. The water is calm, with small pleasure yachts in one of the docks. The only large ship is the ARA Presidente Sarmiento, a handsome old training ship turned museum, permanently moored.

On the other side of the dock rises some of the most expensive apartments in Buenos Aires. Glass towers with river views and tight security. It’s a place popular with the trendy middle class and tourists, perhaps with a touch too much glass.

But there’s the Puente de la Mujer, the modernist pedestrian bridge designed by Santiago Calatrava. It cuts across the dock like a sculpture in motion, sleek and white, rotating to let boats pass. It’s hard to miss and easy to admire. Both a literal and symbolic bridge between the city’s past and its present reinvention.

There’s no salt in the air, no scent of timber, no cargo being loaded, but that’s fine. What the city has in this renovated area really adds value. Buenos Aires needs to look to the future, whilst keeping one eye on its past.

The Puente de la Mujer (Spanish for “Woman’s Bridge”) was built between 1998 and December 2001, at a cost of about $US 6 million. It was funded through a donation by a certain Alberto L. González.

It is a steel and reinforced concrete pedestrian bridge, 170 metres long, wide 6.20 metres, and the height of the pylon is 39 metres. It weighs approximately 800 tonnes. Structurally, it is a cantilever spar cable-stayed bridge combined with a swing bridge mechanism. Apparently the 102 metres long central rotating span is powered by a system of 20 electric motors controlled by a computer system located at the eastern end of the bridge. This mechanism enables the bridge to rotate 90° in about two minutes.

The bridge features a unique asymmetrical design, symbolising a couple dancing the tango. The white inclined pylon represents the male dancer, while the curved deck signifies the female dancer.

In its early years, the bridge faced maintenance challenges. By 2004, just three years after its inauguration, the bridge was temporarily closed due to missing screws and wooden slats, rendering it unsafe for pedestrians. The responsibility for maintenance was a point of contention, as the city of Buenos Aires did not assume responsibility, leaving it to the Gonzales family, who had donated the bridge. However, in 2022, the bridge underwent a significant renovation, during which its flooring was replaced using plastic wood made from recycled bottles collected at the city’s green points.

I guess it’s now owned by the city, since they were involved in the 2022 renovation.

Parque Thays

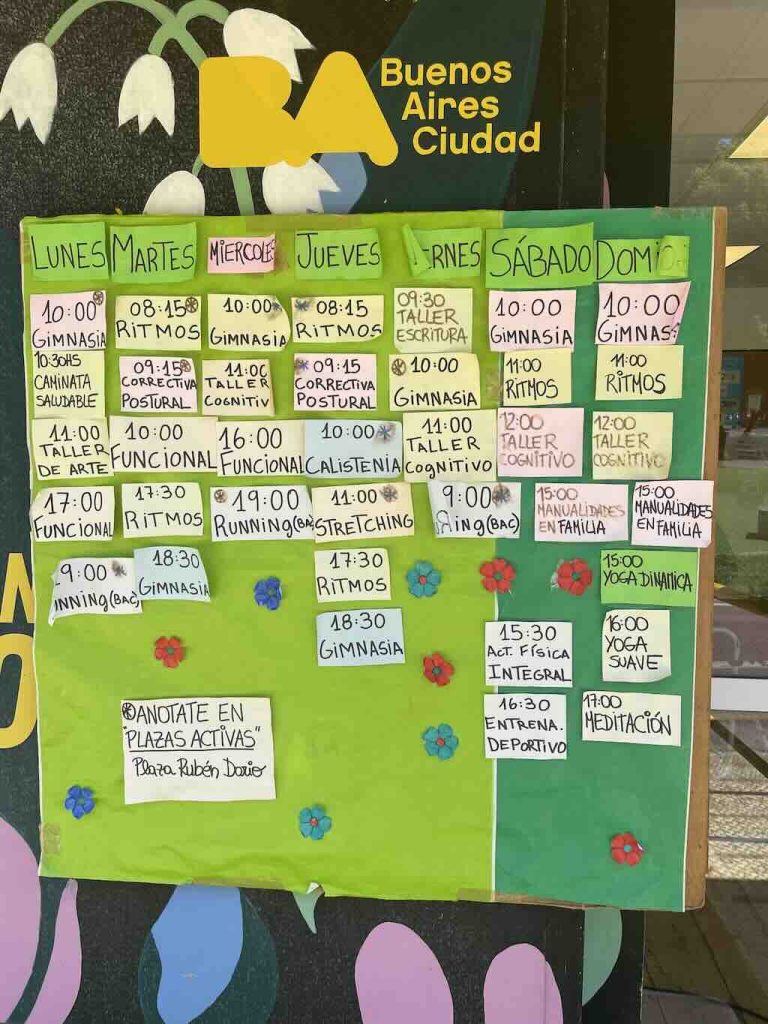

Buenos Aires is a big city, but it’s also a great place to walk. I walked to the museums, and one of those walks was through Parque Thays. It was a Sunday, the joggers were out, lots of people were doing gymnastics in the open park, and I even had my pulse and blood pressure checked at a stand set up on the promenade. Luckily they said I would probably make it back to Europe, if I stopped smoking (I don’t), didn’t take drugs (I don’t), and do more exercise (I try).

And the famous Jacarandá trees were in bloom, with their striking purple flowers.

The park is named after Carlos Thays, the French-Argentine landscape architect responsible for designing many of Buenos Aires’ iconic parks. The park was established on the site of former amusement park, which closed in 1990 after a fatal accident. The land was later turned into a public green space.

The only blot on an otherwise very pleasant public park, is the above building. The building is Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de Buenos Aires.

This is what architectural historians call Stripped Classicism, a trend where classical forms were retained but stripped of ornamentation, producing an austere, imposing, authoritarian feel. This was common in both US governmental buildings and in the Fascist and Stalinist architectures of the same era. In the US, this style was used to project federal authority without the “European baroque” exuberance, keeping buildings sober but grand. The use of enormous fluted columns without bases (columnas dóriques sin basa), massive podiums, and symmetrical facades is reminiscent of buildings like the Lincoln Memorial (1922), the US National Archives (1935), and even certain Federal Courthouses built between the 1920s and 1940s in Washington, D.C.

In Buenos Aires, this style translated into this hybrid of Beaux-Arts orchestrated massiveness but without the delicate ornamentation of, say, French-inspired Buenos Aires buildings from the early 20th century (layered façades, domes, and lavish sculptural decorations). The Facultad de Derecho was commissioned and its construction started under populist and nationalist Juan Domingo Perón, during his first presidency (1946–1955). The original plan was to make this part of a grand Civic Center (Centro Cívico), consolidating state power on the banks of the Río de la Plata. However, most of that plan was never executed. It is clear that the authorities wanted a classical, monumental, hieratic, and elitist building, something that mirrored Mussolini’s and Stalin’s neoclassical tendencies.

The intent is clear. The classical orders (columns, symmetry, stone, repetition) tell you that the law is not something you can shape, it is immutable. The facade is closed, hermetic, impenetrable, it suggests order, not discussion. The raised podium forces you to ascend, giving reverence to the building and those who occupy it.

But it is not a government building, it is a building for students learning law. It shouts solemnity, formality, and exclusivity, a world apart from everyday life. It tells students that if they master the codes of law, they will become elite guardians of a sacred knowledge. The law is not presented as a tool for the people, but as a profession you must qualify for, prove yourself worthy of, and access through difficult, exclusive rituals. The architecture mirrors this by making the building physically unwelcoming and emotionally distant.

I hate this type of building, it is designed to filter and transform law students into an elite class of priests of a civic religion. One that is supposed to serve people, but whose architecture reveals its true bias – to dominate, to formalise, to separate the judged from their justice.

Justice deserves a better building, and perhaps better occupants.

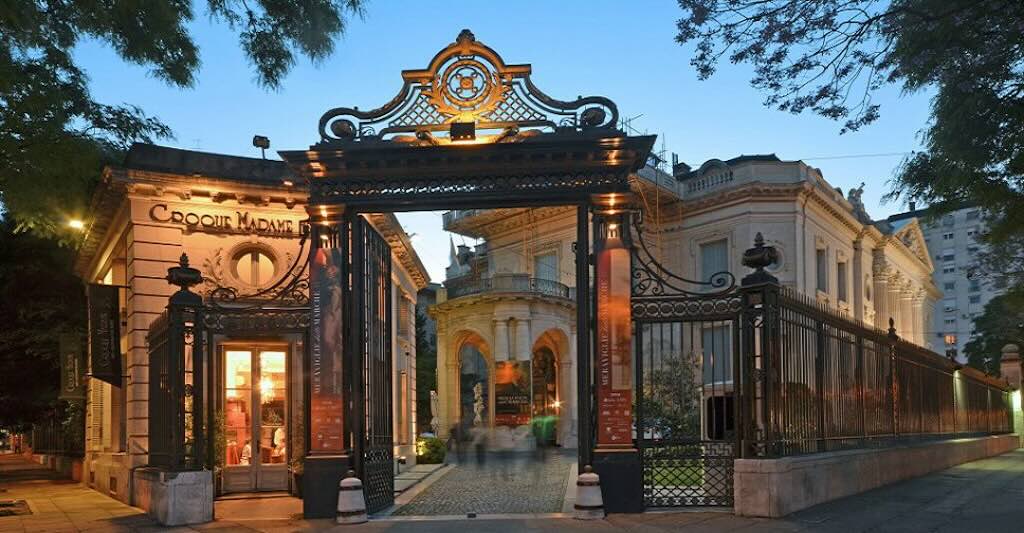

Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo

The Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo (National Museum of Decorative Arts) is housed in the elegant Palacio Errázuriz-Alvear, a Beaux-Arts mansion built between 1911 and 1917 by French architect René Sergent. Inspired by 18th-century French architecture, the building boasts intricate woodwork and gilded salons, reflecting the opulence of the Belle Époque in Buenos Aires.

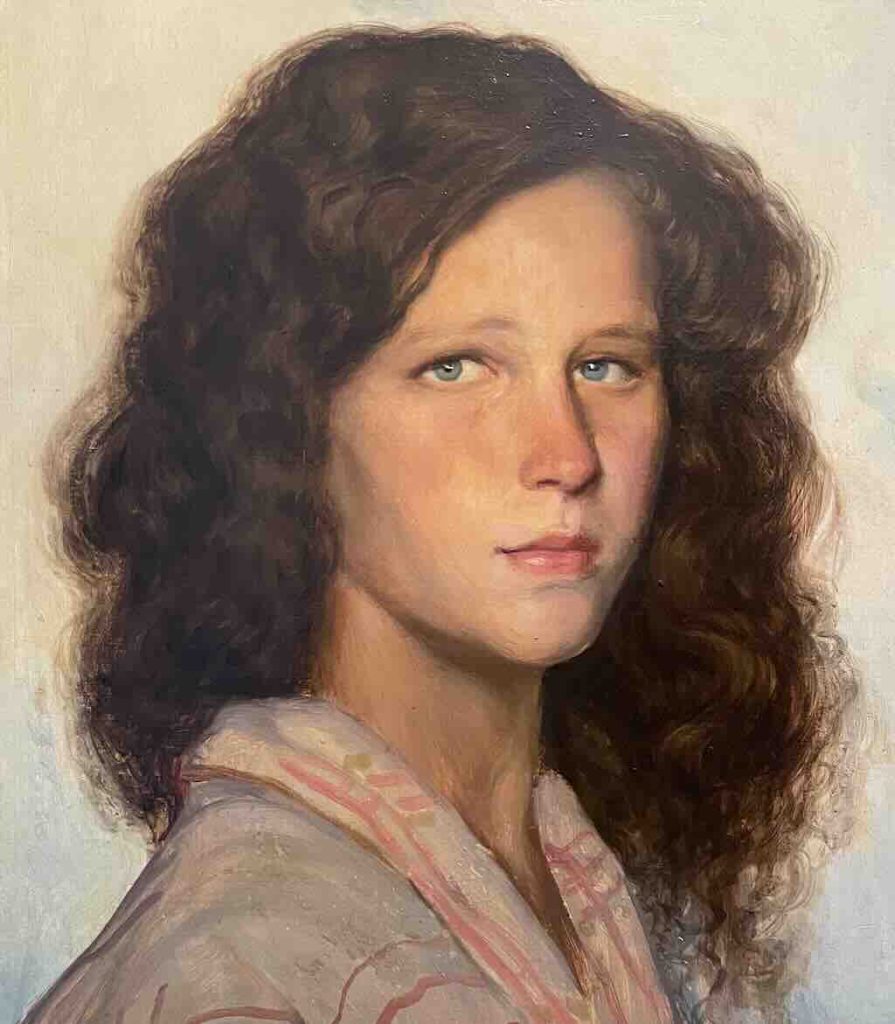

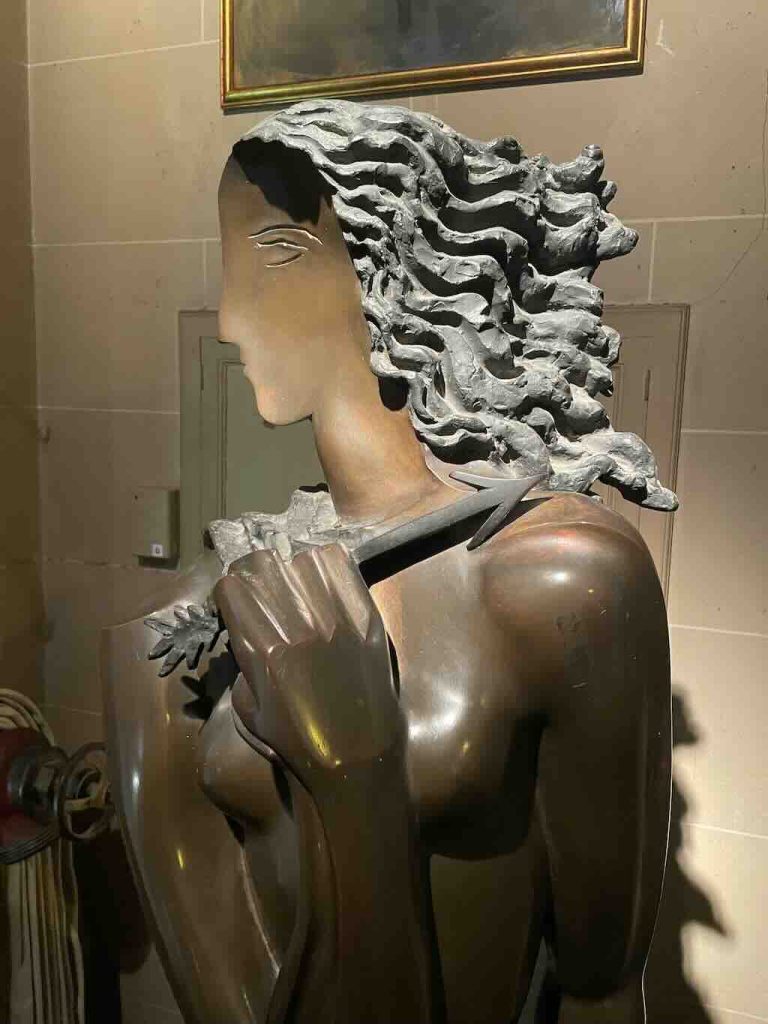

Inside, the museum presents a collection of European decorative arts, including French and Spanish furniture, tapestries, porcelain, silverware, and Oriental art, alongside notable paintings and sculptures.

It’s a small museum, easy to visit, and “easy on the eye”. I have selected just a few items that I found particularly attractive, starting with…

Both are Chinese “famille rose“, and both are pairs from different periods. On the left we have a vase from the Kang-Hi epoch (1662-1723), and on the right, a vase from the Chien-Lung epoch (1736-1796).

“Famille rose” refers to a specific type of Chinese porcelain decoration characterised by the use of enamel colours dominated by pink (rose) tones, derived from colloidal gold. The term was coined by French collectors in the 19th century.

People look and read the tag, but never ask how do you get pink from gold, and what’s so special about pink anyway.

Firstly, the imperial workshops were actively experimenting with new enamel colours, having already mastered underglaze blue, celadon (jade green), copper reds, and famille verte greens. Pink is a soft, delicate, colour neither bold like red nor sharp like blue. So it opened a new visual language that allowed them to mimic peonies, lotus, peaches, and human complexions more realistically. This was essential in Chinese symbolism, where flowers and fruits carried coded meanings of longevity, wealth, fertility, and harmony. Pink could now be used to represent these motifs with subtlety.

Secondly, in Chinese aesthetic philosophy, pink (a softened red) was seen as balancing. Red is associated with life, luck, joy, and fire, so yang. Pink softened it into a gentler, more yin-friendly tone, suitable for domestic settings, intimate gifts, or refined court use, rather than public display.

Thirdly, the production of gold-pink enamel was difficult and costly. Not every kiln could master it. The preparation of colloidal gold, firing without discoloration, and achieving an even surface required immense skill. Its rarity naturally elevated its status. Anything difficult to make becomes precious. This was an early example of the luxury through scarcity principle.

Finally, when famille rose reached Europe it surprised collectors, merchants, and royal courts. European porcelain factories had just begun experiments with enamel colours, and suddenly there was a delicate, soft, glowing pink and pastel palettes unknown in Europe. The famille rose became one of the most prized categories of export porcelain in the 18th century.

The pink colour in famille rose enamels comes from gold nanoparticles suspended in a glassy enamel matrix. At the time the word nanoparticle did not exist.

When pure gold is ground extremely finely and dispersed into tiny particles (colloidal form) within the enamel, it exhibits a phenomenon called surface plasmon resonance. This is a property where the free electrons on the surface of the gold nanoparticles resonate with certain wavelengths of light.

For gold particles of the right size (typically around 20 to 100 nanometers) this resonance selectively absorbs part of the visible spectrum and reflects a soft pink to ruby-red hue.

So the colour is not the result of a dye or a pigment in the traditional sense. It’s an optical effect caused by the interaction of light with nano-sized gold. The finer the dispersion, the subtler and softer the pink. The slightly milky, tender quality of famille rose pink comes from this gold-glass interaction.

Therefore the famille rose is not so much defined by the colour, as by the use of opaque overglaze enamels applied after the porcelain is fired and glazed.

What we see here are some of the classical motifs used, including flowers, birds, courtly scenes, and auspicious symbols (e.g. bats, dragons, the phoenix, cranes peaches, the lotus, even elephants and cats in some regions).

When we look at the two vases from different periods, what do we see? In the later period, Chien-Lung, we see creamier white, a softer luster, a larger and richer palette of more vivid colours, and a flatter looking surface. The vases are also more highly decorated, with phoenixes, dragons, peonies, and some European-looking floral scrolls. Designs are more crowded, showing a greater control over what must go where.

Joseph Pollet (1814–1870)

La Noche (The Night)

ca. 1848–1855

White Carrara marble, life-size

Trained in the neoclassical studios of Bertel Thorvaldsen and Pietro Tenerani, Joseph-Michel-Ange Pollet (1814–1870) developed a sculptural language marked by purity of form and emotional subtlety. La Noche presents a striking and tender allegory of Night (Nix).

Commonly known as Joseph Pollet, he was born in Palermo, Italy, but I think he was of French nationality. He practised and exhibited in Paris, earning the prestigious Legion d’honneur for his work in 1856. His subjects ranged broadly from the historical, ecclesiastical, classical, and allegorical.

The present model, with the full title “Une heure de la nuit”, gained Pollet wide recognition when he exhibited it in plaster in the Paris Salon in 1848. While it was on display he was quickly approached for the rights to edit it, and both Empress Eugenie and the Ministry of the Interior requested a version of it. Since this exhibition, the composition has been reproduced in several sizes and in different materials. A marble version was exhibited at the Louvre and is now in the Museum of the Second Empire at Chateau de Compiègne, a French royal residence built for Louis XV. The first bronze version of the model was exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in 1855, which was edited in various sizes by the foundry of E.Colin & Cie.

The marble version of the plaster original was ordered on the 12 June 1848, for 12,000 francs. The block of Carrare marble was delivered to Pollet on 23 June 1848. However, Pollet judged that it would be difficult to create the same composition in marble, and demanded and received an extra 3,000 franc for a different marble block. This allowed him to include a second figure at the base in addition to the original drapery, stabilising the whole. The completed statue is known to have been shown at another Salon in 1850.

The female figure rises gently, in a composition marked by subtle movement and quiet introspection. Her head is held high, yet her eyes are closed, creating a fascinating duality between movement and sleep.

Both arms are raised, but rather than reaching out, they are bent at the elbows, with the hands delicately resting behind her head, as if adjusting or cradling her elaborate hair. This gesture is neither theatrical nor monumental, it is soft, reflective, and deeply human. Her hair is entwined with flowers, each petal treated with care.

The figure’s body is lightly draped. A cloth cascades from her right hip, balancing the upward movement of the composition. It does not obstruct her form but rather reinforces the vertical movement, suggesting an effortless ascent. The composition is designed so that all visual lines subtly lead upwards, from the small child at her feet, through the flow of the drapery, and ultimately to the figure’s poised head and raised arms.

At her feet, partially emerging from the base itself, is a small winged child. The child holds a small bouquet of flowers and has tiny wings folded against his back, unmistakably recalling the traditional representations of Sleep (Hypnos). His gaze is directed gently upwards towards the rising figure of Night, reinforcing the connection between the two.