In late 2024 I went on an explorer cruise to the Antarctic. And going to the Antarctic meant going through Buenos Aires. I had never been to South America, so I decided to include some days before and after the cruise to do some sightseeing.

This post is Part II, describing (or more truthfully, inspired by) my visit to Buenos Aires in November-December 2024.

Visiting Buenos Aires (Part I)

Visiting Buenos Aires (Part II) including:-

- La Boca – A Historical Perspective

- Buenos Aires – from Failure to Foundation

- Silver, Smuggling and Slaves

- Was Potosí the Richest Strike in History?

- Tell Me More about Life in the Potosí Mines

- How Did the Silver Get from Potosí to Spain?

- The Spanish Treasure Fleets (Flotas)

- The Feria de Portobelo

- Why Was a 400 Ton Galleon Only Carrying Around 6 Tons of Silver?

- A Galleon – A Floating Fortress

- What About the Silver Route Through Buenos Aires?

- What Did Galleons Carry From Spain to South America?

- Where Did All the Silver Go?

- How Did Spain Spend Its Silver in Europe?

- Did the Silver Make Spain the Richest Country in the World?

- And Argentinian Independence?

In addition check out my visit to the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

This post is also one of a series describing my entire trip, including:-

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 1-7)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 8-11)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 12-17)

- Planning a Cruise to the Antarctic

- My Antarctic Packing List

- Le Lyrial – A Luxury Expedition Cruise Ship

- Le Lyrial – Exploring Hidden Engineering

- Air Dolomiti Embraer E195

- Lufthansa Business Class Lounge, Frankfurt

- Lufthansa Boeing 747-8 – Business Class

- Ministro Pistarini International Airport, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Meliã Recoleta, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Sofitel Recoleta, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Palladio, Buenos Aires

- Lufthansa Boeing 747-8 – First Class

- Lufthansa First Class Lounge, Frankfurt

La Boca - A Historical Perspective

The first thing to note is that even the most simplistic history of La Boca can’t be described by just looking at the perimeter of the barrio as defined today. It must include the role played by the entire Río Matanza-Riachuelo.

As a reminder with Río Matanza-Riachuelo, the Río Matanza refers to the entire river and Río Riachuelo is the name used for the last stretch that flows into the Río de la Plata at the La Boca.

Until May 1786, the Riachuelo had a single outlet that emptied up near barrio Puerto Madero. In fact after the meander known as the Rocha bend, when it reached its current mouth, the Riachuelo actually turned north almost at a right angle. It ran parallel to the coast until it opened somewhere in the present-day Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur. It’s been suggested that it might have been more or less in line with the present day Calle Humberto 1º. It would appear that around 1600 there were three natural “pozos“, a kind of sheltered water. One of which was very near the original mouth of the Riachuelo “where ships wintered”. The three natural shelters were connected by a channel that began in the Retiro or Palermo shore, and continued to the mouth of the Riachuelo.

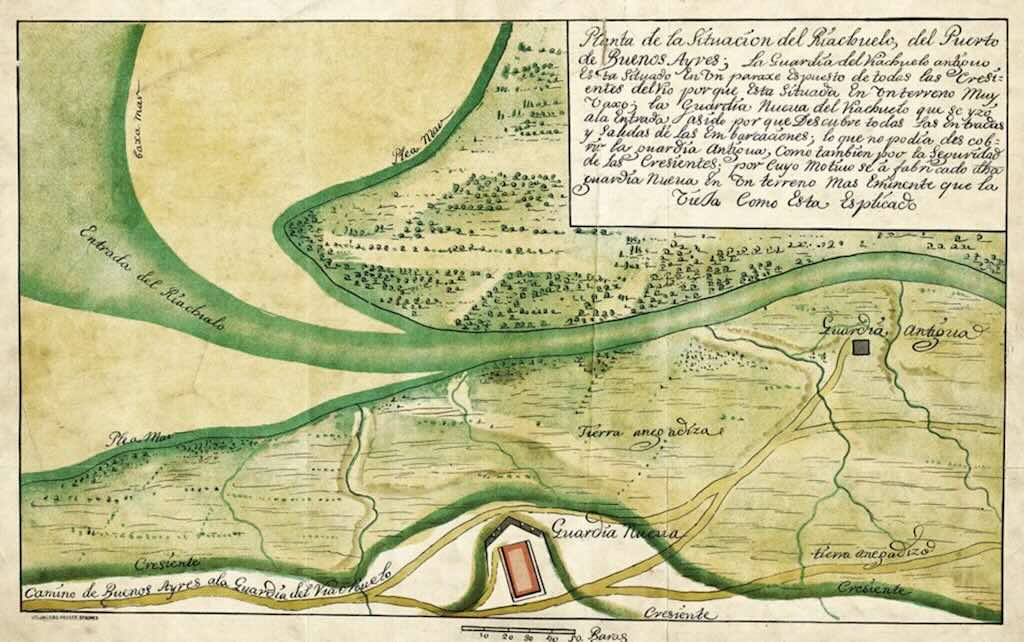

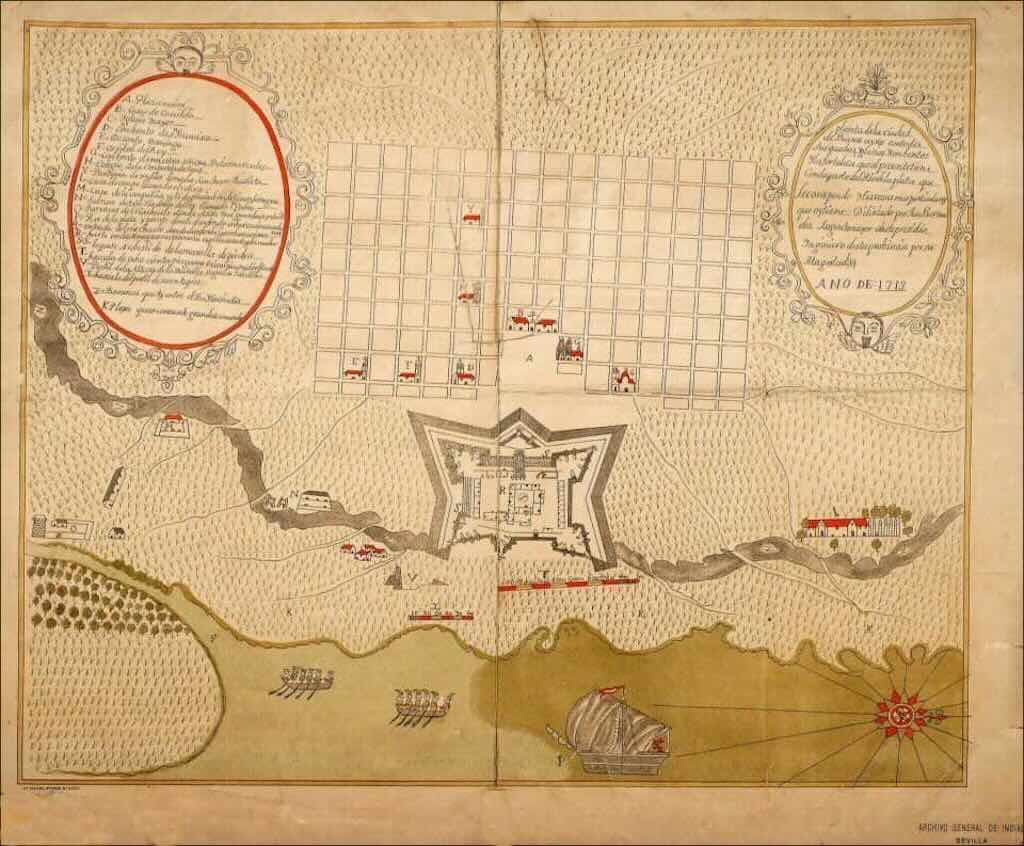

The above drawing is not dated, and the below map dates from 1718. Both clearly show the Riachuelo turning and exiting in front of the city.

In another map dated 1709, it shows “the Riachuelo channel with 3 feet of water” with dotted lines. It also showed that the channel opened at the level of the current Plaza de Mayo. So the idea is that ships arriving had to stop at the convent of Las Mercedes, then proceed through the channel to the mouth of the Riachuelo. Once in the Riachuelo they could go upstream to the place that in the 18th century was called Las Barracas (today a barrio of the city).

In fact in 1575 the Riachuelo was so important it was called Río de Buenos Aires, and only later took the name Riachuelo. However, ships had to stop in a different natural harbour, anchor, and wait for the tide, to then take the channel to Riachuelo. It was said that “they enter a river so narrow that only two ships fit in its width”, but the river “has so much depth that ships of a thousand tons could be in it, although no ship that requires more than eleven palms of water (about 220 cm) can enter through its mouth, and even that must be done by swelling the sea…”.

Already during the 15th and 16th centuries many types of ships were being built – namely three- or four-masted carracks, caravels with both lateen and square sails, pinnaces, the small oared șaicas and the multi-decked galleons. The use of the compass became widespread and made longer and longer voyages possible (e.g. Columbus’s expedition is considered the first recorded transatlantic voyage where the compass played a crucial role). Ships of up to a thousand tons were already being built, e.g. the Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai (built ~1520s) was one of the earliest confirmed 1,000+ ton European ships.

So it would appear that the Riachuelo was from the beginning the most comfortable port and refuge that Buenos Aires could offer to ships.

The area at the mouth of the Riachuelo was originally marshland, periodically flooded by the river’s tides. During the colonial period, it was uninhabited, and the meadows only exploited by small groups of ranchers and workers. Some documents mention that one of the first settlers in La Boca was the English soldier James Brittain, who in 1817 bought the so-called “Juncales de La Boca” from the Dominican friars. And there is apparently even the mention that in the Juncales de Brittain, the first cricket match in Buenos Aires was played in 1819. For completeness, Juncales comes from junco, meaning reed, a common plant in wetlands. The suffix -al in Spanish often forms collective nouns indicating a place full of something, so juncal means a place full of reeds. Juncales (plural) = places where reeds grow abundantly, often used to describe marshy or riverside zones.

We mentioned above the Rocha bend, well this is in fact what today is known as the small bay in front of Calle Caminito. And still in 1882 it had not changed much from 1536. It was just a long, narrow bend in the river. It was only in 1882 that work started to make the bend into a safe anchorage (seguro fondeadero). As far as I understand things, no one knows when this Rocha bend first appeared. Some very early plans show it, others don’t.

The reality is that the northern access channel to the Riachuelo ceased to be navigable in the first decade of the 18th century and completely disappeared a century later.

However, in May 1786, or perhaps a little earlier, an event occurred on the southern coast of the Riachuelo that greatly attracted the attention of all the inhabitants of the city.

The waters of the Riachuelo opened a “hole” (boquete) in the strip of land that separated it from the Río de la Plata and established a new outlet letting in water “with great ease”. The first person who discovered this new mouth was a boatman who was working in that part of the Riachuelo and who was known to the people by the name of the Trajinista. For this reason the new eastern mouth of the Riachuelo was called the mouth of the Trajinista.

I’m not 100% convinced about the formality of the name Trajinista, although it is certainly used in many references, official and otherwise. However, trajín is the act of bustling about, going back and forth, carrying loads, or doing repetitive work or errands, especially related to trade, transport, or logistics. And a trajista or trajinista is a person who carries goods, moves cargo, or is constantly busy transporting or trading, often informally or without being part of an official system. So the word has many means, from a small-scale trader or peddler, through to a day labourer involved in transporting goods between towns, farms, or markets, and someone who manages or organises the movement of goods in a port or inland transport hub. However, in Río de la Plata and colonial contexts, trajinistas were the small traders or boatmen who used small, flat-bottomed boats or canoas chatas (flat canoes) to carry goods along rivers, streams, and wetlands where larger vessels could not navigate. These boats were ideal for the low waters, reed beds (juncales), and muddy channels around the Río de la Plata. So trajinista was just a name for a small-boat operator who fed the cities from the rivers, working the wetlands and estuaries with their small flat-bottomed craft.

In 1790 some thought the channel would open, but then later would also become blocked. However, with the southeasterly storms of the preceding year and successive efforts at drainages, the gap enlarged considerably and boats could again wait for the tides and enter the river.

In fact the first proposal was to close the gap. But since no one took on the task, in 1791, with great wisdom, it was decided that the “Trajinista gap” had taken a lot of “growth” and that “since it had not occurred to them at the beginning to close it” any work that was done in this direction would demand “great expenses… with a burden on the public and commerce”, so the most convenient thing was to leave it as it was. From that moment on, they never again thought of closing the new mouth of the Trajinista.

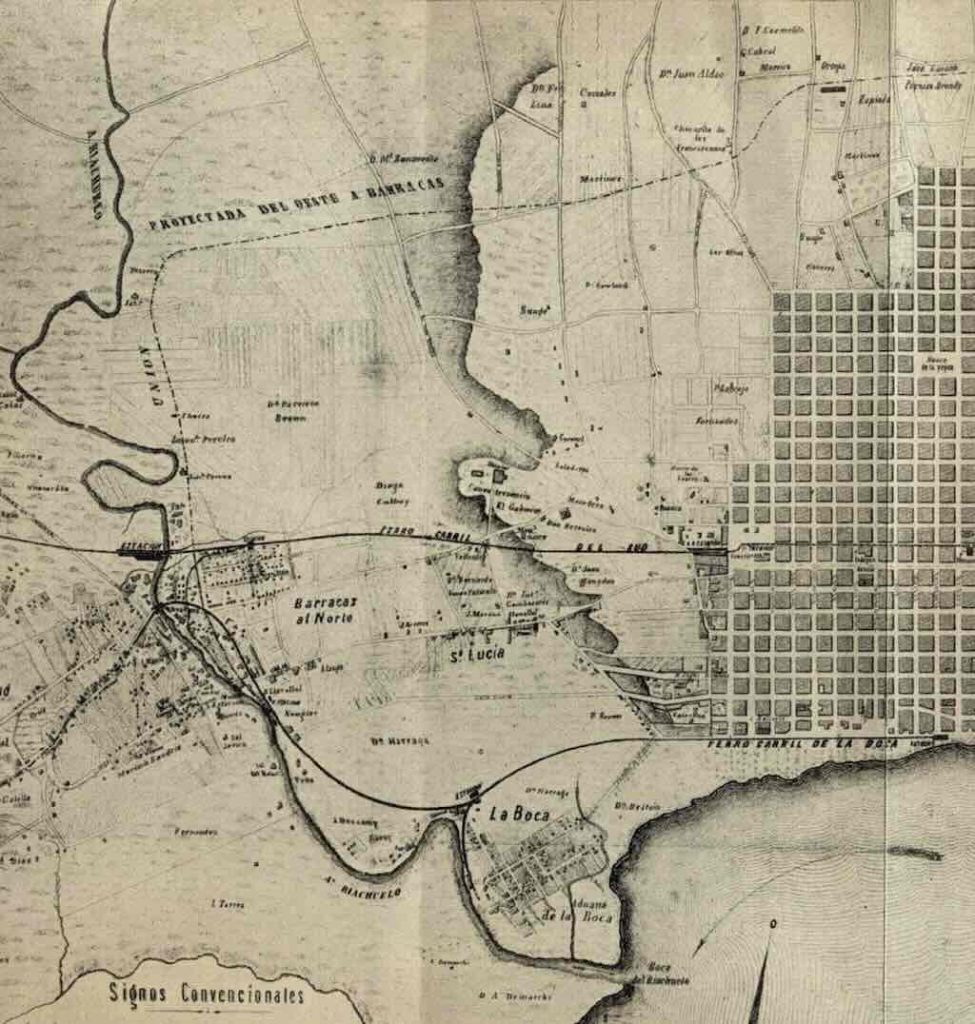

Above we have a detail from a plan of 1866. We can see the ‘new’ Riachuelo exits directly to the sea, and the ‘old’ channel has completely disappeared (replaced by a railway line). We can also see that the Rocha bend ‘near’ La Boca, is still just a bend.

My guess is that La Boca was originally built on the banks of the old channel, and when the old channel started to close up, it was simply built over as La Boca expanded.

Buenos Aires - from Failure to Foundation

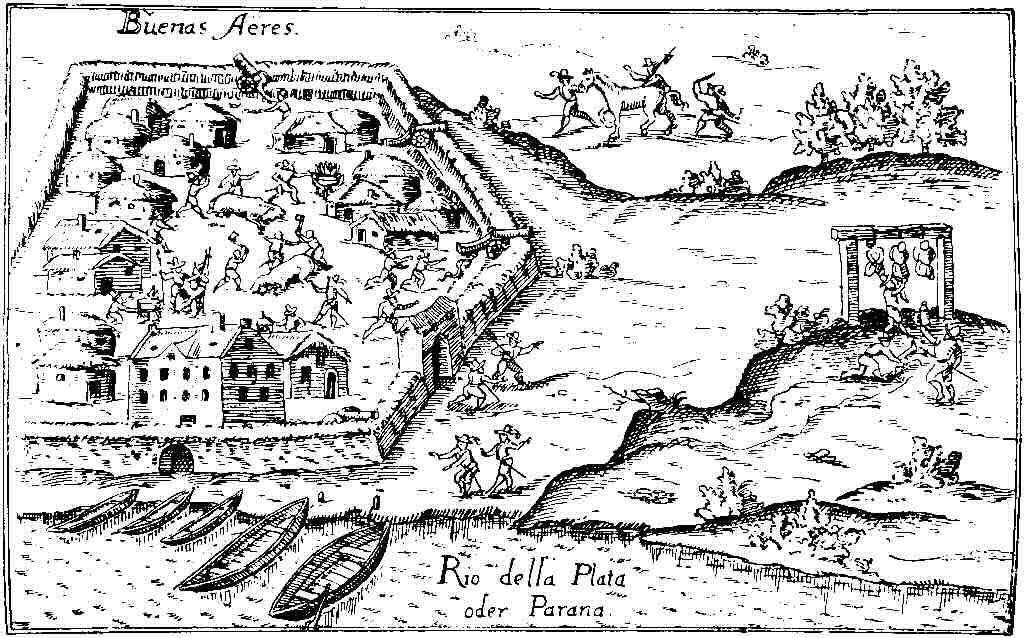

So Buenos Aires was first founded on February 3, 1536, by Pedro de Mendoza, a Spanish conquistador, in an area called “alto de San Pedro” (today San Telmo). And the settlement was called Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Ayre, in honour of the Virgin of Bonaria, patron of sailboats.

It was built on the “río pequeño” (little river), the original mouth of the Riachuelo, a natural harbour where all ships could take refuge and be safe. In February 1542, a certain Pedro Estopiñan Cabeza de Vaca saw a mast “en la entrada del puerto, junto donde estaba asentado el pueblo” (at the entrance to the port, next to where the town was settled).

Early settlers cultivated the land nearby, and marvelling at that river’s periodic flooding “todo lo riega” (irrigates everything). Initially, the Spanish, led by Pedro de Mendoza, established cordial relations with the local Querandí who supplied them with food. But these peoples were nomads and led a subsistence economy, so relations soon became tense, because the Spanish demanded what they did not have to give (“no tenían para dar“). When the indigenous people stopped supplying food, the Spanish reacted with force, sparking the conflict.

I’m not sure what the general historical consensus really is, but the story goes that the Querandí warriors ambushed a Spanish force near Buenos Aires, possibly on or around June 15, 1536, during the Feast of Corpus Christi, hence the name “Batalla de Corpus Christi“. The indigenous fighters used bows, spears, and fire arrows, while the Spanish had horses, swords, and firearms. Despite Spanish military technology, the indigenous forces overwhelmed and defeated the Spanish troops.

It was said that many conquerors (or invaders) succumbed and Don Diego de Mendoza, Don Pedro’s brother, also lost his life. The Spanish were defeated, and this battle was part of a broader siege of Buenos Aires that eventually led to the abandonment of the city around 1542.

As with many places in the world, facts are often linked with myths. On April 28, 1538, the Genoese León Pancaldo’s expedition arrived at the settlement of the “first Buenos Aires”. His ship ran aground in the Riachuelo with a pile of merchandise. He had to sell it all by force, receiving only a few bills of exchange that he was never able to collect. They say, however, that he buried a treasure before the first European inhabitants of this land saw it. He never returned to unearth it. Some maintain that it is buried in the La Boca neighbourhood.

The second and permanent foundation of Buenos Aires happened on June 11, 1580, by Juan de Garay. This time, the settlement survived and developed into the city we know today. So while the first foundation was in 1536, Buenos Aires as a lasting city really dates from 1580.

On October 24, 1580, Juan de Garay distributed the lands on the outskirts of the new city. He granted ownership of the lands situated on the right bank of the Riachuelo to the Adelantado Juan de Torres de Vera y Aragón, and the lands on the left bank, up to the city limits, to Captain Alonso de Vera. These lands, on both sides of the Riachuelo, were swampy and floodable on their banks, but fertile and with excellent pastures inland.

Silver, Smuggling and Slaves

Don Diego Rodríguez Valdéz y de la Banda was the first governor who suggested building some kind of defence to guard the Riachuelo. Finally some kind of fort was built. It was said to have prevented smuggling, but otherwise to have been “una construcción miserable“. Still it survived until 1674. Later the fort was converted into a customs house and was used for unloading ships. But as a reminder, the fort and harbour on Riachuelo were outside the city of Buenos Aires, and there were continuous complaints about the condition of the road linking them. Even the 900 inhabitants of “Alto de San Telmo” were isolated and left without food when rain destroyed the local roads.

Even as we read through the early history of Buenos Aires, the Riachuelo, and La Boca, we have forgotten to ask “Why?”.

Why did the Spanish establish Buenos Aires? What was so important about the ships that arrived and left Buenos Aires? And what about those smugglers, operating in the middle of nowhere?

Let’s start with some one-liners to set the scene:-

- 1492: Christopher Columbus, sailing for Spain, reaches the Caribbean, marking Europe’s first contact with the Americas.

- 1498: Columbus glimpses South America, but 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral claims Brazil for Portugal.

- 1519: Hernán Cortés, a Spanish conquistador, lands in Mexico, and by 1532, Francisco Pizarro, another Spanish conquistador, invades the Inca Empire.

- 1545: Silver is found at Potosí (modern Bolivia), the richest strike in history.

- By 1560: Spain controls the world’s largest silver supply, fueling its empire and Europe’s economy.

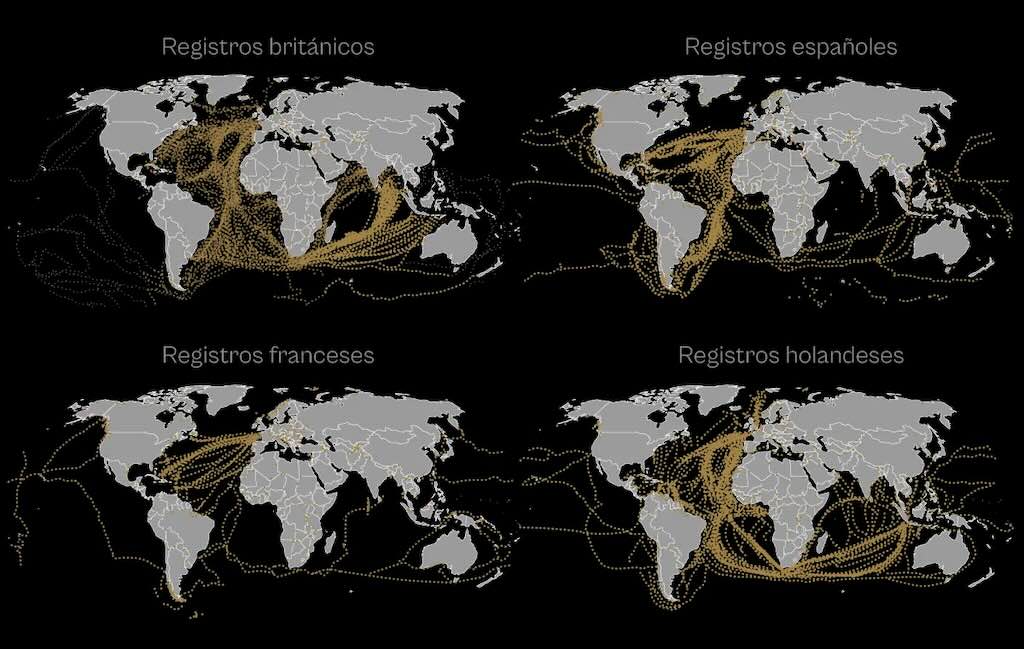

- The Ships: Spanish galleons formed treasure fleets sailing across the Atlantic.

- Annual convoys: 30–50 heavily guarded ships moved silver from the Americas to Seville.

- Buenos Aires (founded 1580): A backdoor for silver, bypassing Spanish control via smuggling.

- Contraband thrives: Silver leaks through Portuguese Brazil and British, Dutch, and French pirates.

- By the 17th century: More silver left the Americas unofficially than through Spanish ports.

It was Lima that served as the administrative and commercial hub of Spanish South America, enforcing the imperial trade monopoly by controlling legal exports of Potosí’s silver and regulating commerce with Spain.

Lima’s role as the administrative and commercial hub of Spanish South America was firmly established by the late 16th century, particularly after it became the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1542 and the seat of the Real Audiencia of Lima in 1543.

The reality is that the Spanish established and maintained Buenos Aires primarily as a strategic outpost to block Portuguese expansion and secure an Atlantic access point for their South American territories.

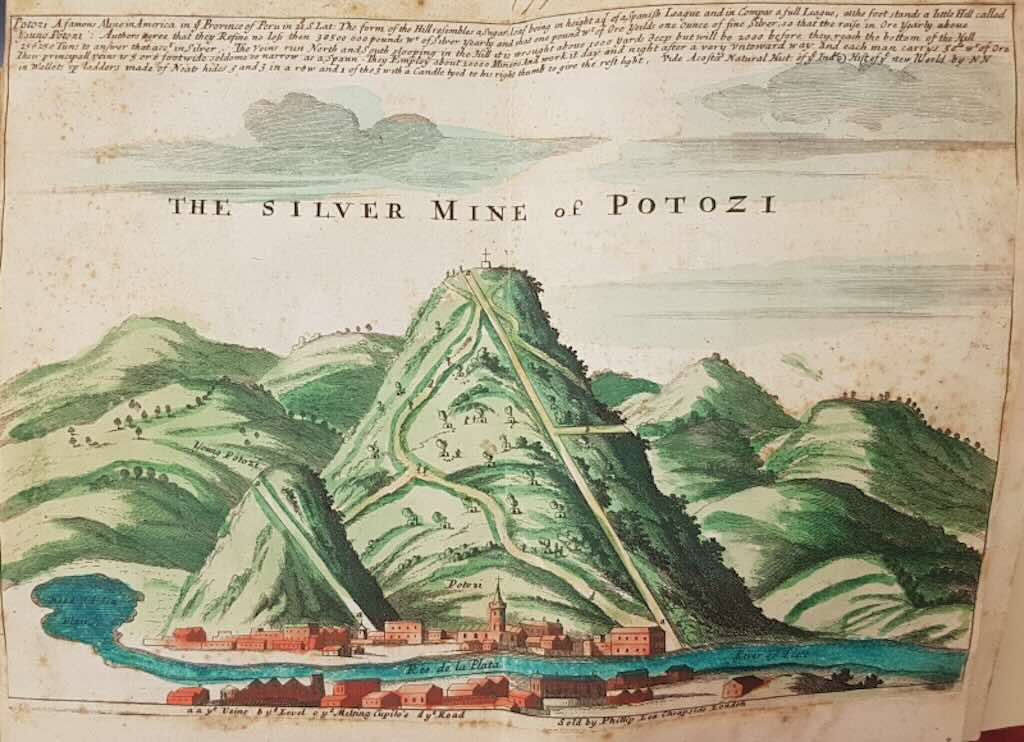

Was Potosí the Richest Strike in History?

Arguably Potosí was the richest silver strike in history, but more important it changed world history.

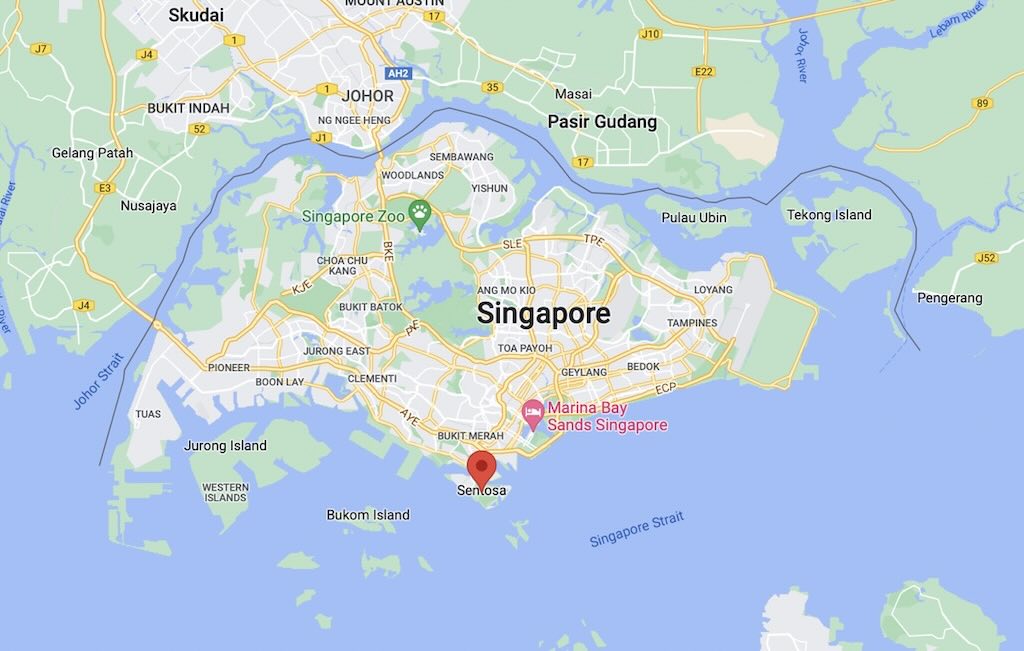

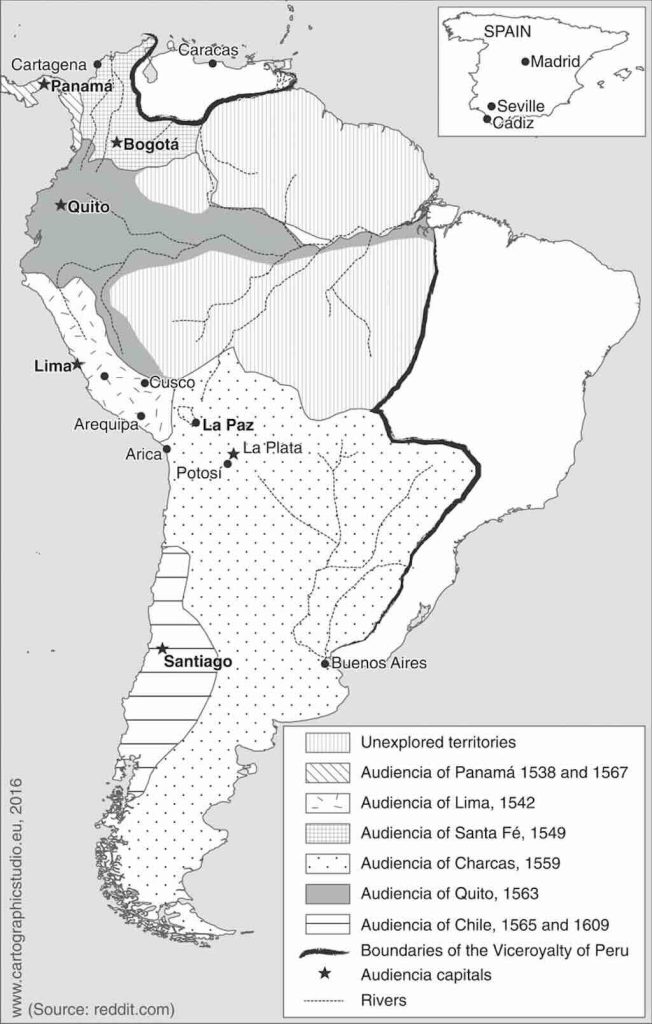

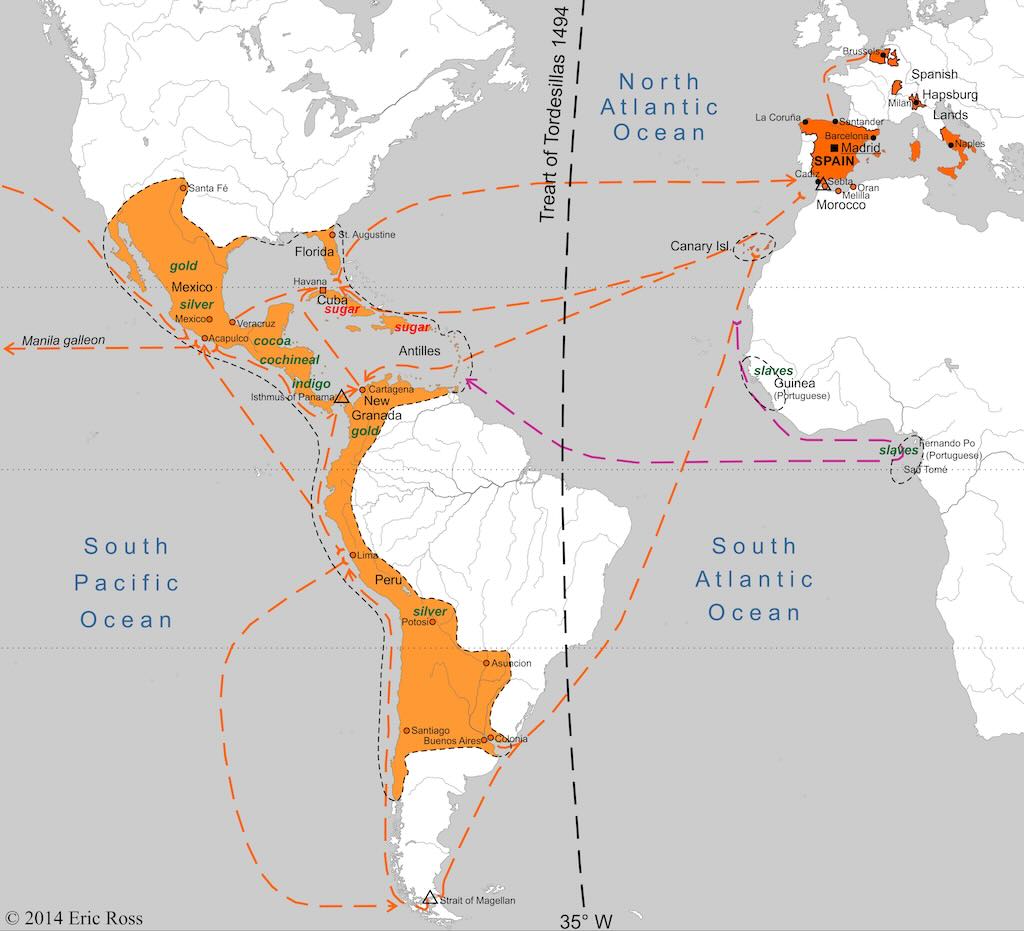

It’s actually quite difficult to find a decent map showing the location of Potosí in a historical context. We can see clearly where the silver mine is, and immediately see the obvious logistic difficulties that had to be overcome in moving from mining a mountain in the middle of nowhere to holding a silver coin in Madrid. We can also see how Buenos Aires is clearly still a peripheral city in the 1500s, so another challenge is also see what role it will play in the coming centuries.

In Spanish America, an Audiencia was a high court (Real Audiencia) and a key institution of Spanish colonial administration. But it wasn’t just a court, it actually functioned like a regional government combining judicial, administrative, and sometimes legislative and even military authority. Each Audiencia presided over a large district called an audiencia district.

When the Spanish discovered silver at Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain) in 1545, it became the largest single source of silver the world had ever seen. By the late 16th and 17th centuries, Potosí was producing over half of the world’s silver supply, fuelling the global economy and fundamentally shaping world history.

How big was Potosí’s silver output?

The total production of silver (16th–18th centuries) was over 60,000 metric tons, with an annual peak production (c. 1600) of 150-200 metric tons per year. Given that a peso was around 27g of silver, that’s equivalent to 1.5-2 million pesos annually. Potosí alone supplied 60%+ of Spain’s colonial silver.

Silver production varied, in the early 1500s it was less than 200 tons per year, but in the 1600s it peaked at ~500+ tons per year, and by the late 1700s it declined as mines were exhausted.

By comparison:

- California Gold Rush (1848-1855) produced ~3,800 metric tons of gold.

- Klondike Gold Rush (1896-1899) produced ~1,250 metric tons of gold.

Potosí outproduced all of these by a huge margin, making it the most significant single silver deposit ever exploited.

What did Potosí’s wealth mean?

The discovery and exploitation of Potosí transformed global trade, geopolitics, and economies in ways no other single mining strike ever had.

Spain became a global superpower

Potosí funded the Spanish Empire, making Spain the wealthiest and most powerful European nation of the 16th-17th centuries. Spanish kings used Potosí silver to wage wars across Europe (e.g., against the Dutch, English, and Ottomans). The silver paid for the Spanish Armada (1588) and decades of military expansion.

Silver became the first global currency

Potosí’s silver flooded global markets, creating the first true global trade network. In Europe it funded military campaigns and fuelled the rise of capitalism. In China, the Ming and Qing Dynasties demanded silver as tax payments, making Spanish pesos the dominant trade currency. In India & Middle East it paid for textiles and spices. In Africa it helped finance the transatlantic slave trade. And in Japan they had to increased their own silver mining to compete.

How did the Spanish discover Cerro Rico?

Pedro Cieza de León, a Spanish conquistador and chronicler, provided one of the earliest European descriptions of Cerro Rico in his work “Crónica del Perú” published in 1553 (part one, part two). He included a woodcut illustration of the mountain, depicting access paths to the initial veins discovered, along with two indigenous workers. Cieza de León noted the immense wealth extracted from the mountain, stating that such riches of silver had never been seen or heard of before. He also described how the indigenous people used wind-powered furnaces, known as “guayras“, to extract the metal.

Antonio de Herrera, another Spanish historian, recounted the discovery of Cerro Rico in his “Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las islas y tierra firme del mar océano,” published in 1601. He attributed the discovery to an indigenous man named Gualca (also spelled Huallpa), who was of Chumbivilca origin from a province near Cusco. According to Herrera, while Gualca was chasing llamas that had strayed, he grabbed onto a tussock of grass to prevent a fall, inadvertently exposing a rich silver vein. Recognising the mineral due to his familiarity with mining, Gualca reported his find, leading to the exploitation of the mountain’s resources.

Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, a mestizo historian born to a Spanish conquistador and an Incan noblewoman, offered a different perspective in his “Comentarios Reales de los Incas“, published in 1609. He recounted that during the reign of Inca Huayna Cápac, around 1462, the Inca visited the region near present-day Potosí. Upon observing the mountain, then called Sumac Orcko, Huayna Cápac speculated that it contained abundant silver. He ordered his subjects from Colque Porco to mine the mountain. However, as they prepared to begin work, they reportedly heard a thunderous noise and a voice declaring that the mountain was reserved for others who would come later. This event led the Inca to abandon the mining endeavour, and the mountain became known as “Potojsi” a term believed to mean “great thunder” or “bubbling up” in the indigenous languages.

So the Incas already knew about the mountain, but for religious or logistical reasons, they had not fully exploited it. Silver was considered sacred, associated with the moon (quilla), and their mining efforts had focused more on gold and easier-to-access silver in places like Porco.

The Spanish had already established silver mining in Porco, just 30-40 km away. This means that they were actively scouting nearby hills, valleys, and mountains when Cerro Rico was stumbled upon.

Finding Potosí had nothing to do with luck. Indigenous guides, porters, and miners had centuries of localised mining experience, which the Spaniards exploited systematically after conquest.

Of course, this begs the question, how did the Spanish discover the earlier Porco silver mines.

In fact, Porco was already known and mined by the Inca Empire long before the Spanish arrived. The Incas operated Porco using local mit’a labour to extract silver, which was then used for rituals, decoration, and state wealth, but not for monetary circulation. Around 1538, during the first campaigns led by Diego de Almagro and later by Pedro de Candia and Gonzalo Pizarro, the Spanish were told by local chiefs (curacas) of the region about the rich silver mines at Porco. So the Spaniards did not “discover” Porco, they “inherited” it. And it was the first major silver supplier for the Spanish in the southern Andes before the discovery of Potosí in 1545.

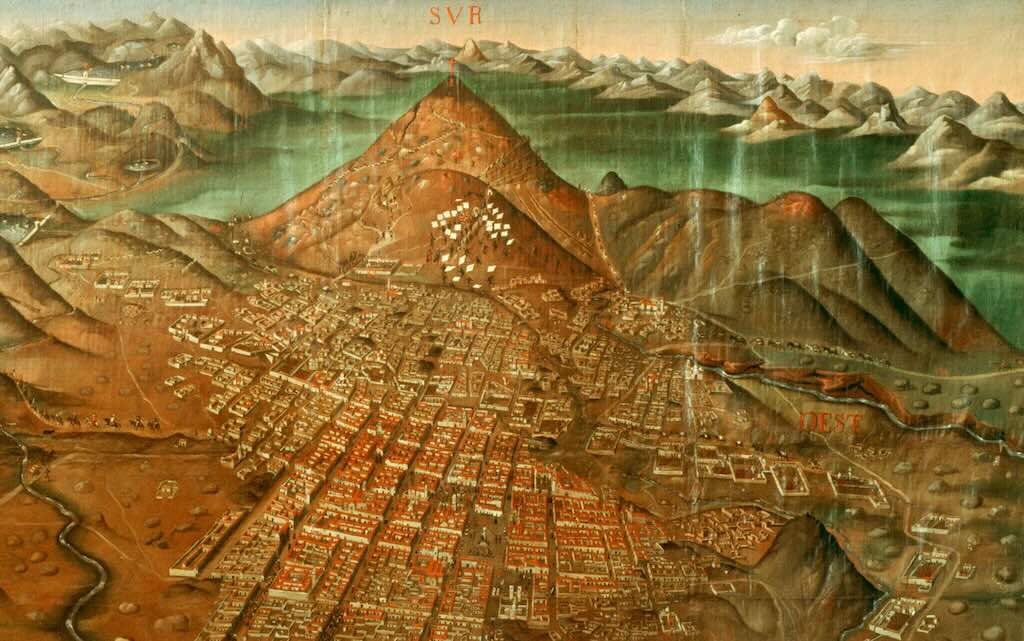

Potosí became a boomtown

By 1650, Potosí had 160,000+ residents, making it not only the largest city in the Americas, but also one of the largest cities in the world at the time (rivalling London & Paris). The silver reinforced the divide between the Spanish elites and the indigenous labourers, a divide that increased almost exponentially. There was a famous saying, “Worth a Potosí” (meaning unimaginably rich), used in Don Quixote (1605).

Unimaginable riches with an unimaginable human cost

The mit’a system forced tens of thousands of Andean workers into the mines, with many dying from exhaustion, mercury poisoning (from refining silver with mercury), and cave-ins. African slaves were also brought in when indigenous labour collapsed.

Some estimates suggest 8 million people may have died from mining-related causes over the centuries.

Why did Potosí decline?

By the 18th century, silver production declined as the richest veins were exhausted. More silver strikes in Mexico & Peru reduced Potosí’s dominance.

The Spanish Empire declined due to overspending, wars, and inflation, and the global economy shifted as Spain lost its economic primacy.

Remember silver was more important than gold

Silver and gold were not treated the same in the 16th and 17th centuries, though both were highly valued. Silver was the backbone of global trade and everyday transactions, while gold was used for high-value reserves (royal treasuries), elite wealth, and prestige (gold was too valuable for most types of transactions). The two metals had different roles due to their availability, economic functions, and demand across different regions. The biggest driver was when the Ming Dynasty adopted a silver-based tax system, and were prepared to pay a premium for it (see the Manila Galleon trade).

The Spanish peso de ocho (pieces of eight) became the first world currency, used in Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Gold was the “Metal of Kings and Empires”. It was hoarded and used in diplomatic gifts, religious artefacts, and elite jewellery, but the economies of Spain, France, and England relied on silver. And remember gold was not standardises like the Spanish silver peso.

Tell Me More about Life in the Potosí Mines

The Cerro Rico de Potosí, towering over the Bolivian altiplano at around 4,750 meters above sea level, was once the richest source of silver in the world.

Labour force

At its peak in the early 17th century, Potosí hosted a population of approximately 160,000. The labour force came from a vast area and was made up of:

- Indigenous Mitayos: Under the colonial mit’a labour system (instituted in 1573 by Viceroy Francisco de Toledo), about 13,000 indigenous men were conscripted each year from 16 Andean provinces. This labour draft affected a territory over 500,000 square-kilometres. Workers served for a year, then waited another six years before potentially being called again.

- African Slaves: An estimated 30,000 Africans were imported to compensate for the declining indigenous population. These workers often perished within months due to the high altitude, poor working conditions, and exposure to toxic substances.

Free Labourers, Mestizos, and Spaniards: Managed operations, refined silver, and operated the mint. These skilled workers oversaw technical aspects of mining and processing, including furnace operation and coin stamping.

Labour was distributed across stages of production:

- Extraction: ~60% of the workforce was dedicated to subterranean mining, working in dark, humid shafts with minimal ventilation and illumination.

- Ore Crushing and Amalgamation: ~25% of the labour force processed ore using quimbaletes and arrastras.

- Smelting and Casting: ~10% of workers were specialised in metallurgy.

- Minting: ~5% worked at the Casa de la Moneda.

The quimbalete was a traditional Andean ore-crushing device. It was a type of manual grinding mill, basically a primitive, human-powered ore crusher. The mechanism consisted of a large, seesaw-like wooden beam, balanced on a central pivot or stone. On one end of the beam, workers would sit or jump up and down, using their weight to lift and then drop the other end of the beam, which held a heavy metal or stone crushing plate. This repetitive movement would pulverise silver-bearing ore, breaking it down into fine particles before it went into the next stage of processing. The quimbalete became a symbol of the brutal mix of forced labour and manual ingenuity in the early years of colonial mining, before water-powered stamp mills (ingenios) became dominant.

- Tunnel Dimensions: Main adits were approximately 1.8 meters high and 2.5 meters wide. Secondary tunnels were often less than 1 meter wide. Some vertical shafts descended over 200 metres.

- Total Tunnel Length: The cumulative tunnel network is estimated to have exceeded 500 kilometres.

- Ventilation: None in most mines, so oxygen deficiency and heat accumulation were severe issues. Carbon dioxide and methane buildup were common.

Lighting: Tallow lamps or candles provided minimal illumination, contributing to fires and accidents.

Ore was carried out by hand in leather sacks weighing 25–45 kg, often by boys aged 10–14, or in woven baskets slung across the backs of Indigenous workers. Animal-powered winches (malacates) were eventually introduced in larger mines.

Extraction tools, included iron pickaxes, chisels, sledgehammers, and gunpowder (charcoal, sulphur, and saltpetre) used from the mid-17th century. Blasting required hand-drilled boreholes ~30–50 cm deep.

Grinding tools, included quimbalete and arrastra.

Ore washing, involved lavaderos, channels and vats used to separate heavier ore particles using hydraulic sorting. They were clay-lined, often 1.5–2 metres wide and 10+ metres long.

Smelting furnaces, guayras, were clay towers ~0.5–1 meter wide, 1–2 meters high, open at the top, wind-assisted. And were used for direct smelting of high-grade ore. In addition “hornos de fundición“, blast furnaces with forced air via bellows, were. introduced later. Fuelled by llama dung (caloric value ~6,000 kcal/kg), as wood was scarce.

Casting involved using clay or sand ingot molds. Standard ingots weighed ~25–30 kg. Marked with royal insignia, assayer’s marks, serial numbers, and sometimes owner’s marks.

Introduced to Potosí in 1572 by Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, the Patio Process enabled extraction from lower-grade argentiferous ores (particularly chlorargyrite and native silver in quartz matrices). It consisted of several detailed steps:

Ore Grinding: Ore was reduced to <0.5 mm particle size using arrastras or quimbaletes to increase surface area.

Slurry Formation: The ore dust was mixed with water, ~6–8% by weight sodium chloride (NaCl), and trace amounts of copper sulfate (CuSO₄) as a catalytic oxidizer.

Amalgamation with Mercury (Hg):

~0.3–0.5 kg of mercury was added per kg of silver.

The mixture was spread 20–30 cm thick on open-air patios (typically 50 x 100 meters).

Mules or workers trampled the mixture for 20–30 days, allowing mercury to chemically bind with silver (forming Ag-Hg amalgam).

Washing and Separation: The slurry was transferred to wooden troughs. Lighter waste rock floated off, and the heavier amalgam was collected.

The amalgam was placed in closed ceramic retorts and heated to ~357°C (boiling point of mercury).

Mercury vapour was condensed and reused, and the remaining silver was ~99% pure.

Historical studies estimate over 8 million deaths at Potosí (including indirect deaths) from the 16th to 18th century, with mercury poisoning a leading contributor.

Ingots: Typically 25–30 kg silver bricks. Sometimes converted into piñas, disk-shaped silver masses.

Coin Production at Casa de la Moneda:

Macuquinas (Cobs): Irregular hammered coins, with common denominations including 1, 2, 4, and 8 reales.

Columnarios (from 1767): Milled, machine-struck coins. The “pillar dollar” became the prototype for later currencies, including the US dollar.

The coins bore the mintmark “PTS” or “P” (for Potosí), assayer initials, and the Pillars of Hercules design. Coins from Potosí were accepted globally, particularly in Asia where they were traded for silk and spices.

How Did the Silver Get from Potosí to Spain?

The silver from Potosí followed a well-established route to Spain, known as the Spanish Treasure Fleet system, which was designed to transport vast amounts of wealth while minimising the risk of piracy and shipwrecks.

Firstly, historians estimate that between 1500 and 1800, Spanish America (mostly Potosí and Mexico) produced around 150,000 to 180,000 tons of silver. As already mentioned Potosí alone is believed to have yielded ~60,000–80,000 tons of silver from the 16th to 18th centuries. In addition Mexican mines (Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Taxco) produced a comparable amount, if not more. Remembering that Potosí was the largest single silver mine, but Mexican mines probably produced more silver collectively than Potosí, at least 70,000–90,000 tons. In any case this means a rough average of 500–1,000 tons of silver was mined per year over 300 years.

Not all the silver was officially shipped to Spain, some was smuggled, some was shipped to China, and some remained in South America. I’ve not seen a really comprehensive analysis but my guess is that around ⅔ (67%) went to Spain through official channels, about 35,000 tons (21%) went to China and India (some went through Spain before reaching Asia), around 15,000 tons (9%) stayed in South America (local trade, mining costs, salaries, corruption, and infrastructure), and probably around 5,000 tons (3%) was smuggled (mostly through Buenos Aires).

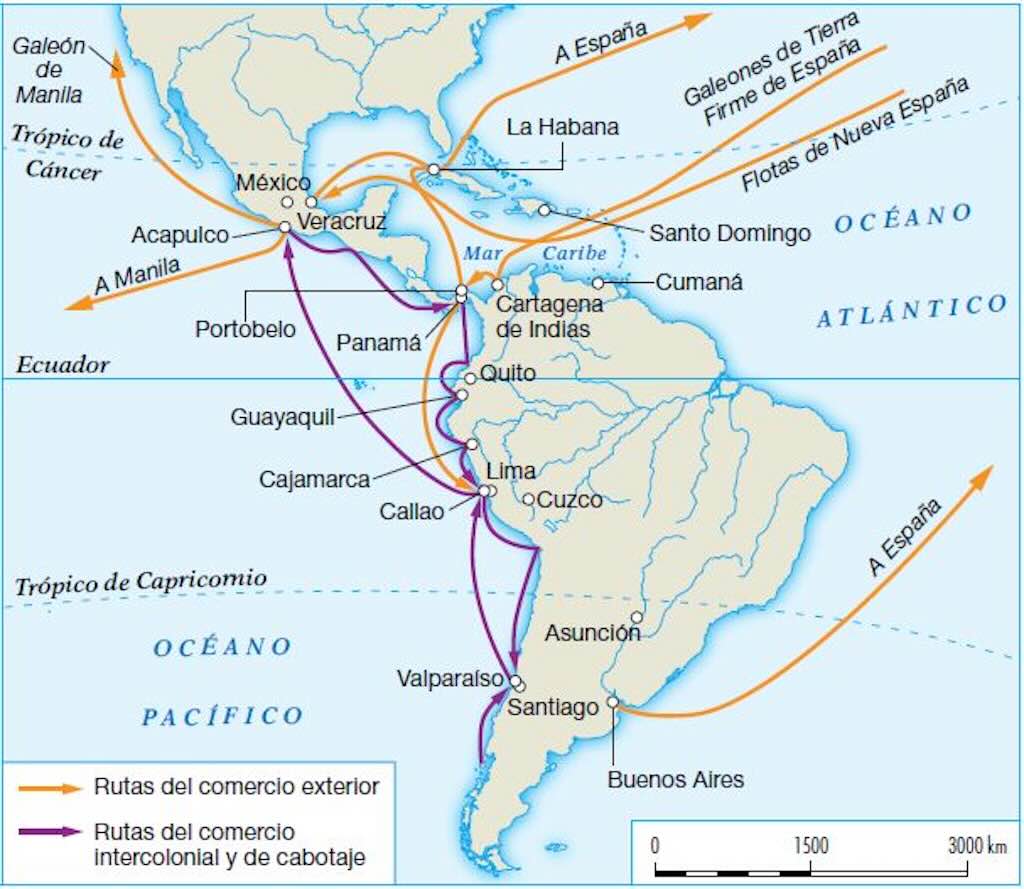

Lima–Panama–Seville

This was the primary route used from the mid-16th to the 18th century. It started overland across the Andes from Potosí to Arica on the coast (now in northern Chile). This was about 800-900 km and the silver was transported by mule caravans. This journey took 20–30 days. Each mule carried 2–4 silver bars (each bar weighing ~25 kg). A large shipment used 3,000–8,000 mules.

At Arica the silver was loaded on to ships for a trip of ≈1,500 km to Callao (Peru), taking 10–20 days, depending on the winds.

Why stop in Callao?

Callao was the main Spanish Pacific hub and the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Silver from Potosí was either stored temporarily in warehouses before being loaded onto ships heading to Panama City, or coined into pieces of eight before export. Callao was also a commercial hub, so goods from all over Peru, Chile, and Ecuador were consolidated there.

From Callao the silver was taken to Panama City again by ship. A trip of ≈2,600 km, taking another 30–40 days.

Types of ships used

Two primary ship types were used in the Pacific silver route:

Galleons (Galeones)

- Larger, heavily armed ships, typically 400–800 tons.

- Carried silver, gold, and other valuables.

- Sometimes also transported high-status passengers, officials, and clergy.

Urcas (a local type of cargo ship) or Mercantile Galleons

- Typically smaller than galleons, they could carry silver plus other trade goods (cacao, cochineal, wool, and textiles).

- Often used for shorter routes, like Arica to Callao and Callao to Panama.

Smaller ships (brigantines, barques, and chalupas) were sometimes used to shuttle silver from minor ports to Callao before transshipment.

How much silver was shipped?

The volume of silver transported from Callao to Panama varied by year but generally included 2 to 5 million pesos (pieces of eight) per year (≈50–125 tons of silver).

Each galleon could carry several hundred thousand pesos’ worth of silver, and typically, 2 to 6 ships per convoy transported the silver. Some years, over 200 tons of silver were shipped from Callao.

What other goods did these ships carry?

While silver was the most important cargo, Callao–Panama ships also carried gold (smaller volume but more valuable). In addition the ships carried cacao from Ecuador (highly demanded in Spain), Cochineal (used for red dye, from Oaxaca and Peru), and quinine (Jesuit bark), a key medicine from Peru. Then there was wool and textiles (llama/alpaca wool, Peruvian cotton), and Chinese silk, porcelain, spices from Manila.

How many ships carried silver?

Typically, 2 to 6 ships per convoy carried silver from Callao to Panama. On rare occasions, a single large galleon carried the bulk of the silver, but this was risky due to storms and pirates. Some ships carried mixed cargo (silver + textiles + cacao). Other ships in the convoy might escort or carry secondary cargoes.

Dangers and risks

The Callao–Panama route was notoriously dangerous:

- Storms along the Pacific made the journey unpredictable.

- English & Dutch privateers (Francis Drake, Thomas Cavendish, later Henry Morgan) tried to intercept the treasure.

- Delays in Callao sometimes led to stockpiling of silver, attracting piracy, and so the fortress at Callao was crucial for defence.

Panama City to Portobelo was an isthmus crossing of ≈80 km, again via mule train. It took 4–7 days, and again with 3,000–8,000 mules.

To understand what happened in Portobelo, we must first understand that there were a variety of different Spanish treasure fleets.

The Spanish Treasure Fleets (Flotas)

The Spanish Empire operated a highly organised convoy system known as the Flota de Indias (Fleet of the Indies). These fleets transported silver, gold, and goods between Spain and its American colonies. Several distinct fleets operated within this system, each covering a specific route.

We are going to need terms such as “Flota de Tierra Firme“ which were not commonly used as official names in Spanish records, though they accurately describes specific treasure fleets. Spanish sources typically referred to it simply as “La Flota de los Galeones“ (The Fleet of the Galleons) or “Flota de Indias“ in general terms. However, historians and maritime scholars use the term “Flota de Tierra Firme“ to describe the fleet that serviced South America, as distinct from the “Flota de Nueva España“ (which went to Mexico). While this distinction is modern, it reflects the practical division in Spanish maritime logistics.

Official records from Seville’s Casa de Contratación refer to “la flota que va a Tierra Firme“ or simply “los galeones“. The Viceroyalty of Peru sometimes referred to it as “los galeones del Perú” or “los galeones de Portobelo“.

Flota de Nueva España (Fleet of New Spain)

- Route: Seville → Veracruz (Mexico) → Havana → Spain

- Purpose: Transported silver from Mexico (Zacatecas, Taxco, Guanajuato) and Asian goods from the Manila Galleons.

- Cargo from Spain: Manufactured goods, wine, weapons, paper, textiles.

- Return cargo: Mexican silver, cochineal, cacao, sugar, and Chinese silk from Acapulco (where the Manila galleons offloaded).

- Fleet composition: 20–50 ships, heavily escorted.

- Main stopovers: Santo Domingo, Havana, Veracruz.

- Final leg: Havana to Seville (later Cádiz after 1717).

Flota de Tierra Firme (Fleet of the Spanish Main)

- Route: Seville → Cartagena (Colombia) → Portobelo (Panama) → Havana → Spain.

- Purpose: Transported Peruvian silver from Potosí (Bolivia) via Panama.

- Cargo from Spain: Textiles, iron tools, wine, books, arms.

- Return cargo: South American silver, gold, emeralds, and tobacco.

- Main stopovers: Cartagena, Portobelo, Havana.

- Final leg: Havana to Spain.

Flota del Mar del Sur (South Sea Fleet)

- Route: Callao (Peru) → Panama → Acapulco (Mexico) → back to Callao.

- Purpose: Managed Pacific trade between Peru, Panama, and Mexico.

- Cargo from Peru: Silver, gold, Peruvian textiles, and coca leaves.

- Cargo from Mexico: Goods from the Manila Galleon (Chinese silk, porcelain, spices).

- Connected with: The Tierra Firme Fleet at Panama.

Galeón de Manila (Manila Galleon)

- Route: Manila (Philippines) → Acapulco (Mexico) → Mexico City → Veracruz → Spain.

- Purpose: Connected Spanish America with Asia, bringing goods from China, India, and Japan.

- Cargo from Asia: Silk, spices, porcelain, ivory, and jewels.

- Cargo from Mexico: Silver (to pay China), cochineal, cacao.

- Fleet size: Usually one or two large galleons per year.

- Final leg: Goods transferred to the Flota de Nueva España, then shipped to Spain.

Flota de Buenos Aires

- Route: Cádiz → Buenos Aires → Lima (overland).

- Purpose: Established later (18th century) as an alternative to the Panama route.

- Cargo from Spain: European goods.

- Return cargo: Silver from Potosí, hides, and yerba mate.

Flota de Galeones (Galleon Fleet)

- Route: Seville → Americas → Havana → Spain.

- Purpose: This was the main armed escort fleet, responsible for protecting treasure convoys.

- Ships: Heavily armed war galleons protecting merchant ships.

- Final leg: Havana to Spain.

Flota de la Habana (Havana Fleet)

- Route: Local fleet defending Havana and the Caribbean trade.

- Purpose: Protected shipping lanes around Cuba and escorted silver fleets.

The Feria de Portobelo

The Spanish treasure fleets (Flota de Indias) did not depart from Portobelo. They left from Havana, Cuba, but first there was the Feria de Portobelo.

The treasure fair of the Spanish Empire

The Feria de Portobelo was one of the most important commercial events in the Spanish colonial system. It was an annual or biennial trade fair where silver from Peru and Bolivia (Potosí mines) was exchanged for European and colonial goods before being shipped to Spain.

Why Portobelo?

Portobelo (modern-day Panama) was a natural deep-water port on the Caribbean side of the isthmus. It was the endpoint of the overland route from Panama City, where silver from Callao (Peru) arrived. The Spanish built forts and batteries to protect the port from pirates.

What happened at the Fair?

The Feria de Portobelo was a massive commercial event, lasting from one to two months. The Flota de Tierra Firme (the South American treasure fleet) arrived from Spain, carrying manufactured goods (weapons, textiles, ceramics, paper, books, furniture, glassware), wine, olive oil, and other Iberian products. In addition there were some Asian goods (silks, spices, porcelain) that had arrived via Manila galleons to Acapulco, then overland to Veracruz and Havana. And at the same time, smaller ships from Cartagena, Veracruz, and Santo Domingo also arrived.

Silver from Potosí mines (Bolivia) was transported by mules from Panama City. The silver was in the form of ingots, coins (pieces of eight), and bars.

Merchants from Spain, Mexico, and the Caribbean gathered to bid on Peruvian silver. Prices for Spanish goods were artificially high, and many colonists complained about monopolistic pricing. Officials and merchants often engaged in bribery and fraud to secure the best deals. African slaves were also traded, as Portobelo was part of the Spanish Atlantic slave trade.

Departure of the fleet

Once the fair ended, silver and goods were loaded onto the Tierra Firme Fleet, which then sailed to Havana. From there, the Flota de Indias took the treasure back to Spain.

The scale of the silver trade

The Feria de Portobelo handled massive amounts of silver, sometimes 50–100 tons in a single fair. In peak years, silver exports from Portobelo reached 4–5 million pesos (pieces of eight).

Naturally, Portobelo was attacked multiple times. In 1596 Francis Drake sacked the town and looted warehouses, but there was not much to steal at the time. Shortly after the disappointed raid Drake died near Portobelo, and his body was buried at sea in a lead coffin, reportedly near the entrance to Portobelo harbour.

In 1688 Henry Morgan serving as Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica, also sacked Portobelo and held it for ransom. The Spanish authorities paid 100,000 pesos (pieces of eight), a huge amount at the time. Morgan left after looting the city and burning the fort.

The reality was that Portobelo was a small town, but during the fair, it became overcrowded. The result was that many Spanish merchants died there of tropical diseases (yellow fever, malaria).

Decline of the Feria de Portobelo

The fair declined in the 18th century when Spain introduced direct trade routes, bypassing Portobelo. Also by the late 18th century, silver trade shifted to Buenos Aires, avoiding the long Panama route. By 1789, the Feria de Portobelo was officially abolished.

Portobelo to Havana

Ships did not sail directly from Portobelo to Spain. They had to first join the main treasure fleet.

Havana as the main departure port

After the Portobelo fair, the silver was loaded onto convoys heading to Havana, the final assembly point for all treasure fleets before sailing back to Spain.

The Tierra Firme Fleet (Flota de Tierra Firme) carried silver from Portobelo to Havana.

The New Spain Fleet (Flota de Nueva España) brought silver from Mexico to Havana.

Once both fleets arrived in Havana, they merged into a single convoy escorted by war galleons.

Why Havana?

Havana was the key strategic port for Spain because it had a large, well-protected harbour. It ment that the fleet could group together for safety (against pirates and storms), and it was a good place to repair ships before the Atlantic crossing. Finally, it was the last point where Spanish garrisons, supplies, and naval forces could provide protection for large treasure fleets (flotas).

Havana to Seville

So the Flota de Nueva España (from Veracruz, Mexico) would join the Galeónes de Tierra Firme (from Cartagena & Portobelo) in Havana before sailing together to Spain.

They would plan to leave once per year between late July to early September, thus avoid the worst of the Caribbean hurricane season (which peaks in September–October), and aimed to arrive in Spain before winter storms hit the Atlantic.

The total convoy would usually consists of 20–50 ships, with 10–25 galleons carrying treasure and the rest as smaller escorts/supply vessels. The convoy could also include other somewhat smaller merchant ships as well.

A galleons would weight 300–500 tons (some could weight up to 1,000 tons by the late 17th century). Give that a a single galleon would carry 4–10 tons of silver, a single fleet could carry 200–400 tons of silver.

Havana to Seville was ≈7,000 km, and took 50–80 days, depending on weather.

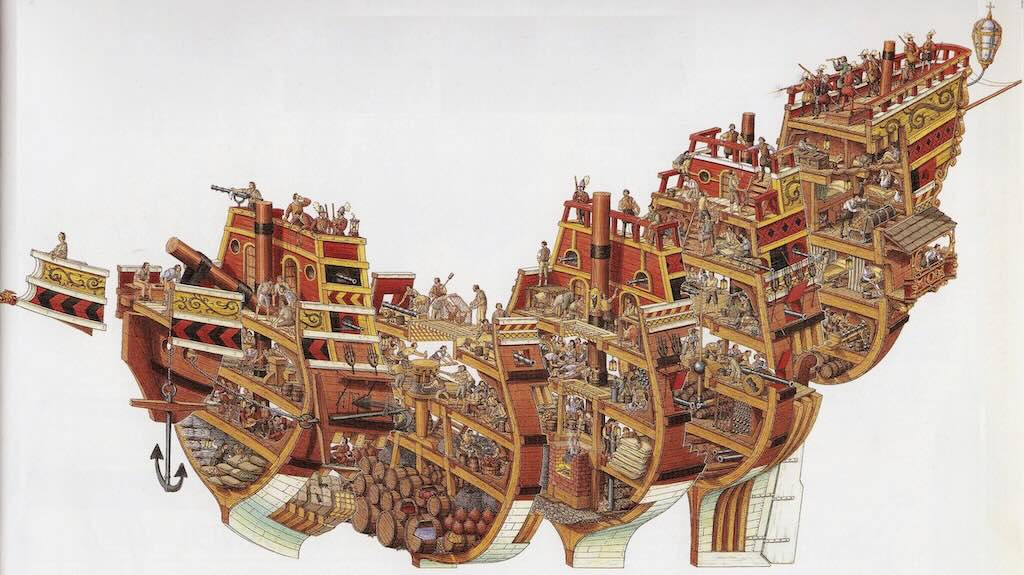

Why Was a 400 Ton Galleon Only Carrying Around 6 Tons of Silver?

We need to breakdown what made up a 400-ton galleon. Firstly, the ships hull, masts, rigging, cannons, and basic fitting took up 200–240 tons (~50–60%), including at least in part about 30-40 tons ship stores & equipment. A fully armed galleon carried 10–30 different types of cannons (average 20 cannons). A 400-ton galleon could carry up to 200+ people, including sailors, soldiers, merchants, priests, and sometimes slaves. Total crew/passenger weighted, including possessions, about 10–16 tons (~5–10%). Food & water for 6 months would weight about 80-120 tons (~20–30%). Livestock would weight 5-15 tons, and the cargo would weight about 80-120 tons. We can see that a 6 month trip would involve a complex balancing act of crew, food & water, and cargo.

Gold and silver were the most valuable parts of the cargo, but they were not the only goods transported. Galleons also carried a variety of luxury goods (silk, porcelain, spices from Asia via the Manila Galleon), dyes and cochineal (used in European textile production), tobacco, cacao, and sugar (profitable colonial products in their own right), and finally weapons, wine, and textiles (sent from Spain to the colonies). Apart from silver and gold, Spanish treasure fleets often carried:

- Precious gems and pearls from Peru.

- Dyewood (e.g. cochineal, indigo) from Mexico.

- Exotic spices, cacao, and tobacco from the Caribbean.

- Fine textiles and ceramics from Asia (via the Manila Galleon).

- Emeralds from Colombia (especially the famous Muzo emeralds).

Another risk with high-density cargo is the free surface effect, when liquid cargo (like barrels of water or rum) or loosely packed cargo (like silver bars or gold dust in chests) shifts in the hold, causing an internal weight imbalance. If silver was packed too loosely or unevenly, sudden shifts could destabilise the ship. Treasure was often placed in well-secured compartments to prevent unexpected movement, often secured within ballast storage areas.

Of course a storm might be the immediate cause of a disaster, but an overloaded hull would have made the ships slower and less manoeuvrable in rough seas.

It’s true that Spanish authorities conducted strict inspections in ports and sealed cargo holds before departure. However, corrupt officials often accepted bribes to look the other way. In the 17th century, Spain imposed a legal cargo limit of 300 tons per ship to prevent overloading. However, many ships ignored this limit and smuggled extra cargo. If caught, smugglers, including captains, could face confiscation, imprisonment, or even execution. Yet, despite the risks, smuggling continued because profit margins were so massive.

A Galleon - A Floating Fortress

A Spanish treasure galleon was at times a floating fortress and at times a floating village.

A Spanish treasure galleon could carried anything between 200-400+ people, depending on the ship’s size and mission. Larger galleons, such as those in the Manila Galleon trade or the Spanish treasure fleet, could carry even more people.

As an example, our 400-ton galleon would have a captain (capitán), a first mate (piloto mayor) 2-4 experienced ocean navigators (pilotos y contramaestres), between 5-20 merchants & crown officials, 50-100 sailors (marineros), 20-50 soldiers (infantería de marina), 10-20 gunners (artilleros), 5-10 carpenters and caulkers (calafates), 1-2 surgeons & medical staff (cirujanos y barberos), 5-15 cooks and stewards (cocineros y mayordomos), 5-10 valet & cabin boys (grumetes y mozos), and a chaplain (capellán), and possibly 0-10 slaves or indigenous labourers, and 0-2 clerks or scribes (escribano). There would also have been a captain of the fleet.

Remember that even a well maintained galleon would take-on several hundred litres of water per day through small gaps, sweating wood, and minor leaks. An old or lightly damaged galleon might take on several thousands of litres per day. Most Spanish galleons had two to four hand-operated bilge pumps. Each pump could remove about 5–10 litres per stroke, with a trained crew working continuously. Caulkers would fill the gaps between planks with oakum (fibres from hemp rope) soaked in tar to close smaller leaks.

Food and supplies needed

A galleon voyage from Havana to Spain or from Manila to Acapulco could last 3–6 months, so provisions had to be rationed carefully.

For everyone onboard there were daily rations.

- Water: 1–2 litres per day at the start of the voyage, but supplies would dwindle over time. Water often became rancid, slimy, and undrinkable due to algae and bacteria growth. By the end of long voyages, daily rations could drop to 0.5 liters per person.

- Hardtack (bizcocho): 0.5–1 kg per day, but it was often infested with weevils and maggots over time.

- Salted Meat: 200–400 g, but fresh meat was mostly eaten at the beginning of the voyage. Later, only salted beef, pork, or fish remained.

- Dried Legumes (chickpeas, Beans, Lentils): were standard Spanish rations.

- Cheese & Olive Oil: 50–100 g per day, though cheese was often rock-hard aged sheep/goat cheese.

- Rice & Maize: More common on Manila Galleons, but in the Atlantic, maize was less common compared to wheat biscuits or dried fava beans.

- Wine & Aguardiente: 250 ml per day of wine, stored in large wooden barrels. Officers got higher-quality Spanish wine (from Jerez, Málaga, or Rioja). Sailors often received cheaper, watered-down wine to stretch supplies (1 part wine to 3 parts water). Wine could also be mixed with stale or rancid water to make it drinkable. Wine turned sour (vinegar) but could still be used for cooking and food preservation. Aguardiente (strong alcohol) and vinegar were added to water to kill bacteria. Aguardiente was issued in small amounts (not a daily ration like wine), as a morale boost after surviving a storm, or on special occasions.

Galleons would also carry livestock, e.g. 100-300 chickens (initially for the eggs), 10-30 goats, 20-50 pigs, and on the larger galleons, even 1-5 cattle. Chickens would be fed scraps from the ship’s rations (biscuit crumbs, maize, old bread), and occasionally fish guts or dried grains. They would be given water-soaked grains or stale water, and were often eaten early in the voyage. Goats ate dried straw, ship’s vegetable scraps, and soaked biscuit, and even dried seaweed. The milk was for the officers and elite crew members, and later the goats were eaten. Pigs ate scraps from crew meals (mostly maize, dried peas, and biscuit dust), and given the bare minimum water. They were eaten progressively during the voyage, and the fat rendered for cooking or preserving meat. Cattle ate hay stored in barrels or packed in a dry compartment, and occasionally soaked hardtack or maize. They were given more water than other animals, but still heavily rationed. Primarily slaughtered for special occasions, and fresh cows milk was highly prized. They didn’t survive the journey, and the meat could be salted and bones used in soups. Salted beef was usually preferred over live cattle.

Weapons

A treasure or merchant galleon might only carry 10–20 cannons, whereas a war galleon escorting the treasure fleets could easily carry 20–40 cannons, or more. A 400-ton treasure/merchant galleon’s cannons varied in size and purpose. It might have 4-8 demi-culverins firing 8–12 lbs shot, 4-10 sakers (5–7 lbs shot) and 4-10 falconets & swivel guns (1–3 lbs shot). The larger cannons (4-10) would be on the lower gun deck able to fire broadside. The other cannons would be on the upper deck, and there would also be stern and bow ‘chasers’ (for retreat & pursuit).

There would be 1.2-2 tons of gunpowder stored in a secure, dry, well-ventilated magazine deep in the ship’s hold (usually near the stern). The gunpowder would be kept in wooden barrels lined with wax or leather to prevent moisture damage. The magazine was kept dark (to prevent accidental sparks), and the crew wore felt-soled shoes when handling powder (to avoid static discharge). Around 200-600 cannonballs and shot (round, chain and bar, grapeshot, canister shot) could weight anything up to 5 tons. They were kept in wooden racks or barrels near the gun decks for quick access.

The crew would also have a stock of small arms, including 50-150 muskets and arquebuses, 20-50 flintlock pistols, 100-300 swords and cutlasses, and 50-100 boarding pikes and halberds.

Mortality rates were high due to disease, malnutrition, storms, and conflicts.

Anything from 15-25% of the crew would die on an Atlantic crossing, mostly from scurvy, dysentery and infections, followed by storms and shipwrecks, and finally from naval battles, etc. Up to 50% died on Manila Galleon voyages (due to extreme hunger, scurvy, and shipwrecks).

What About the Silver Route Through Buenos Aires?

Overland from Potosí to Buenos Aires

- Silver extracted from Potosí was first carried across the Andes by caravans of 10,000-15,000 mules and llamas.

- The silver travelled to Salta and Tucumán, passing through modern-day Bolivia and northern Argentina.

- From there, it continued southeast via Córdoba and then reached Buenos Aires, the main Atlantic port of the Río de la Plata region.

- Potosí to Buenos Aires (overland) ≈2,700 km, and took 3-4 months.

Shipment from Buenos Aires to Spain

- Silver was loaded onto ships that sailed along the South American coast northward toward Brazil.

- Ships either sailed directly to Spain or made stops in Portuguese-controlled Salvador (Bahia) or Rio de Janeiro to resupply.

- From there, they crossed the Atlantic, often passing the Azores Islands, before reaching Cádiz or Seville.

- The ships themselves were usually medium-sized galleons (200-400 tons), and fleets were also smaller than the Caribbean treasure convoys (5-15 ships).

- A ship would carry between 2-8 tons of silver, in the form of bars, ingots, and coin.

- Convoys from Buenos Aires could leave twice a year, but departures were irregular.

- Silver quantities were less than through the Caribbean, but could still add up to 100s of tons per year.

- This trip was ≈10,000 km, and took 60–120 days, depending on weather conditions.

- The total trip from Potosí could take ≈6-12 months, so potentially a little longer than via Havana.

Via Cape Horn

- Some sources mention a southern route around Cape Horn to Buenos Aires.

- This would have been extremely dangerous, and I’ve found no data on its use in real life.

Risks and contraband trade

Initially the Buenos Aires route was less secure than the Caribbean route, making it more vulnerable to smugglers and illegal traders (especially British and Portuguese). The Portuguese in Brazil often facilitated silver smuggling via their colony, allowing silver to be traded illegally in Europe and Africa. British merchants also traded with Buenos Aires, despite Spanish efforts to control commerce.

Initially, the Spanish Crown preferred the Lima–Panama–Havana route because it was easier to control. However, by the late 17th and 18th centuries, the Buenos Aires route became officially sanctioned, as Spain tried to reinforce its presence in the region. In 1776, Spain created the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, which gave Buenos Aires more commercial power and legitimised silver shipments via the Atlantic.

We have to remember that before the Bourbon Reforms Spain restricted direct trade from Buenos Aires to Spain, forcing silver to go via Lima and Panama. The reforms allowed Buenos Aires to legally export silver, and the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata made Buenos Aires an administrative centre for silver trade.

Piracy and wars in and around the Caribbean often made the route through Havana more dangerous, so shipping silver thought Buenos Aires might have been slower, but sometimes it was a safer option.

This silver shipments remained the backbone of the Spanish Empire’s wealth until the early 19th century, when revolutions and British naval dominance broke Spanish control over the silver trade.

What Did Galleons Carry From Spain to South America?

Main cargo from Spain to America:

- Weapons & Ammunition – Muskets, cannons, gunpowder for defence and conquest.

- Iron Tools & Horseshoes – Used for mining, agriculture, and ranching.

- Textiles & Clothing – Fine wool and linen fabrics (especially from Seville and Flanders).

- Luxury Goods – Mirrors, ceramics, cutlery, and glassware.

- Wine & Olive Oil – Essential for Spanish settlers, especially in religious services.

- Paper & Books – Rare and expensive but crucial for the Church and administration.

- Mercury (Quicksilver) – Vital for silver refining in mines (shipped from Almadén, Spain).

- Agricultural Seeds & Livestock – Horses, cattle, pigs, and sheep for expanding colonial farms.

The Lima-Panama route was the most profitable but riskier due to pirates. The Buenos Aires route was smaller but became crucial in the 18th century and fostered black-market trade with Britain and Portugal. Spanish treasure fleets carried much more than just silver, making them the lifeline of the empire. These maritime trade routes fuelled Spanish dominance for nearly 300 years, but by the early 19th century, independence movements and British naval superiority brought them to an end.

Where Did All the Silver Go?

The total silver mined from Spanish America (mainly Potosí and Mexico) between 1500 and 1800 is estimated to be 150,000–180,000 tons. Most of the silver went to Spain, but a significant portion stayed in the Americas or flowed to Asia.

Silver sent to Spain via the treasure fleets

Officially about 100,000–130,000 tons of silver was transported through the Lima–Panama–Seville and Buenos Aires routes. It peaked at 500+ tons per year in the 17th century, and this silver financed Spain’s wars, its empire, and European trade.

Silver that stayed in the Americas

Roughly 20–30% of all mined silver never left Spanish America. This silver circulated within the colonies for trade, infrastructure, and local economies. Silver was coined in New Spain (Mexico), Peru, and the Río de la Plata. Silver was used to pay for work in the mines, mule trains, tools, and mercury (used in refining). Some silver never entered Spanish tax records. By the late 18th century, Buenos Aires had become a major silver smuggling hub due to its connection with British and Portuguese traders.

Silver flowed to Asia via the Manila Galleon

A substantial portion of the silver financed trade with China through the Manila Galleon (1570–1815). Probably 50,000+ tons of silver (about ⅓ of all mined silver) ended up in China and India. Some estimates say more than half of Mexico’s silver was sent to Manila instead of Spain.

The Ming and Qing Dynasties used silver as official currency. China had silk, porcelain, and spices, but only wanted silver in return. The Spanish silver peso (piece of eight) became a global currency, used widely in Asia. And by 1700, China held nearly 50% of the world’s silver reserves, mostly from Spanish mines. Silver also flowed through Mughal India, often traded for Indian cotton and opium.

How Did Spain Spend Its Silver in Europe?

The massive flow of silver from the Americas (100,000–130,000 tons officially) had an enormous impact on Spain, Europe, and global trade. However, much of this silver didn’t stay in Spain for long. The silver quickly spread across Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and Asia due to war debts, trade imbalances, and economic mismanagement.

For example, Spain’s military spending in Flanders alone (for the war against the Dutch) consumed 1.5 million ducats (≈20 tons of silver) annually. The Armada (1588) cost 10 million ducats (~150 tons of silver) but was ultimately a disastrous failure. And the Spanish Crown defaulted on its debts at least four times (1557, 1575, 1596, 1627), unable to sustain its war expenses.

Spain was a consumer economy, importing luxury goods (silk, spices, coffee, etc.) rather than developing its own industries. It borrowed heavily from European bankers and merchants, meaning much of the silver never truly stayed in Spain. Genoese bankers financed Spain’s wars in return for silver payments. Dutch and English merchants often received silver indirectly as war payments. And German and Italian mercenaries were paid in Spanish silver.

Spain could have become a dominant economic power in Europe, but instead it was more like a revolving door, silver in, silver out. By the 17th century, Spain produced little of its own goods, leading to a reliance on foreign merchants. One of the biggest unintended effects of Spain’s silver influx was inflation across Europe, known as the Price Revolution (linked to the high rate of inflation). As silver flooded Spain and Europe, prices for goods skyrocketed, especially food, textiles, and land. Between 1500 and 1650, prices in Spain increased by 400–500%, leading to widespread economic hardship. The poor and fixed-income workers were hit hardest, as wages could not keep up with inflation. Nobles, landowners, and merchants lived comfortably by. simply raising prices.

By 1700, Spain was no longer Europe’s dominant power. Spain’s military losses mounted up (especially against France and England). By the 18th century, Spain was no longer Europe’s financial powerhouse. The British and Dutch had developed capitalist economies, while Spain remained a military empire without an industrial base.

Did the Silver Make Spain the Richest Country in the World?

To compare Spain’s wealth (15th–18th century) with other major powers of the time, we need to use economic indicators that allow meaningful cross-country comparisons. The best available metrics include:

- GDP Estimates – How much each country produced in goods and services.

- Silver & Gold Inflows – Spain’s bullion income compared to total wealth.

- State Revenues – Government income from taxation and trade.

- Purchasing Power & Inflation – The real economic effect of Spain’s silver wealth.

- Relative Economic & Military Power – Spain’s position compared to rival states.

GDP Spain vs. other major powers

Historians have provided rough GDP estimates for early modern economies. While GDP data for 1500–1800 is imprecise, the following estimates (in billions of 1990 international dollars) give a relative sense of Spain’s economic weight.

Over the whole period Spain’s GDP was far smaller than France, China, and India throughout the period. France (18 growing to 24 billion) had between 2 and 3 times the GDP of Spain. The Ming/Qing China (≈100 billion) and Mughal India (≈90–110 billion) were the largest economies during that period. In 1500 Spain’s economy was around twice that of England and the Dutch Republic, but by 1700 their economics were more or less the same as Spain. So Spain never had the largest economy, but its bullion wealth from America did give it disproportionate financial power.

Between 1500 and 1700, Spain received an estimated 150,000–180,000 tons of silver and 16,000–20,000 tons of gold from its American colonies. By 1600, Spain controlled about 80% of the world’s silver supply. The problem was that Dutch, Genoese, and Italian bankers absorbed much of Spain’s silver. Spain spent heavily on wars (vs. Ottomans, Dutch, French, and English). And Spain’s high inflation (the Price Revolution, 16th–17th century) reduced silver’s purchasing power.

Even though Spain had vast silver inflows, its state revenues (tax income) were often smaller than those of its rivals. In 1550 Spain’s government income was less than half of that of France and less than 20% of the Ottoman Empire. Tax income in England and the Dutch Republic was lower, but grew to be about the same by 1700. Spain relied heavily on silver instead of a strong domestic tax system.

Spain suffered from high inflation due to silver imports (“Price Revolution,” 16th–17th century). Silver devalued over time, increasing the cost of military spending. Spain imported most of its goods from Flanders, Italy, and the Dutch Republic, sending silver abroad. By 1650, Spain had spent most of its American silver on wars and debts.

So Spain was not the “richest country” in total wealth, but it was the strongest military power in the 16th century. However, this power declined by the 17th and 18th centuries.

So experts have suggested that Spain was like a “petrostate”, wealthy in bullion but lacking a sustainable economic system. Other countries such as England, by contrast, developed diverse economies that overtook Spain in the long run.

And Argentinian Independence?

The Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata was created to reinforce Spain’s control over its southern frontier and to formalise Buenos Aires’ role in transatlantic trade. However, smuggling remained widespread, and Spain’s attempt to impose a closed market for its own manufactured goods severely damaged local artisanal industries, especially in the interior provinces. This shift disproportionately empowered Buenos Aires’ merchant class, who would control both legal and illicit commerce.

For the leaders of the independence movement, primarily Creole elites, military officers, and liberal reformers based in Buenos Aires, the goal was not only political separation from Spain, but also economic control over the entire viceroyalty. They sought to inherit its full territorial and commercial reach, linking the Atlantic port to the mineral wealth of Upper Peru, especially the silver in Potosí. This vision promised to preserve historical trade circuits while expanding them under the logic of “free trade,” now open to British and other global markets.

But that vision unraveled on the battlefield. The Army of the North, formed in 1810 by the Primera Junta in Buenos Aires, was the main military force tasked with securing Upper Peru from royalist control and incorporating it into the revolutionary project. It was composed largely of Buenos Aires militias, supplemented by recruits and supplies from interior provinces like Tucumán and Salta. Its commanders included Juan José Castelli, who led the first campaign after the May Revolution, and Manuel Belgrano, whose leadership brought both early victories and subsequent setbacks. Between 1811 and 1817, the army suffered a series of decisive defeats, at Huaqui, Vilcapugio, Ayohuma, and finally Sipe-Sipe, each weakening the revolutionary hold over Upper Peru. These losses crushed any realistic hope of reintegrating the Andean mining economy and permanently severed the historic link between Buenos Aires and Potosí.

Even had the territory remained intact, the Spanish imperial trade system faced structural disadvantages. Spanish shipping tonnage lagged far behind its rivals. By the late 18th century, Britain’s merchant fleet displaced over 1.5 million tons, while Spain’s barely exceeded 300,000. British and Dutch vessels were faster, better armed, and more cost-efficient, allowing them to deliver goods more reliably and at lower prices. Spanish manufactures, protected by monopoly, could not compete with the volume or quality of British textiles or Dutch finished goods. By the time independence loomed, the legal Spanish trade routes had become a historical fiction, while contraband and foreign merchants defined the region’s real economic lifelines.

The result was a fractured legacy. Buenos Aires remained commercially ascendant, but the broader promise of a unified, integrated successor to the viceroyalty was lost. It would take another 70 years before Argentina could successfully reintegrate into global capitalism on its own terms.