At 17:00 on 23 December 2023 the light of my life, Monique, passed away. It was the most traumatic experience of my life, but I had to try to find a way to build a new “life view” for myself. Not a “new life” for that would be impossible, just a patchwork view of my future, until my wife and I are united again.

And one small facet of that was to continue to travel, but only to places where my beloved wife would never have want to go. So my first decision was to book an explorer cruise to the Antarctic. My wife hated the cold, and was not particularly attracted to the idea of long-distance flying nor life on a cruise ship.

And going to the Antarctic meant going through Buenos Aires. I had never been to South America, so I decided to include some days before and after the cruise to do some sightseeing.

This post is one of three parts,

Visiting Buenos Aires (Part I), including:

- The “Paris of the South”

- Where is Buanos Aries?

- Why compare Buenos Aires to Paris?

- La Boca – the odd one out

- Plaza de Mayo – Resistance and Memory

- Plaza de Mayo: A Symbol of Death? Or of Rebirth?

- La Boca – a barrio of resilience and identity

La Boca is not just Calle Caminito - The bridges over the Riachuelo

- Argentina’s “crisol de razas“

- Argentina and colonial capitalism

- Buenos Aires and the world of the working woman

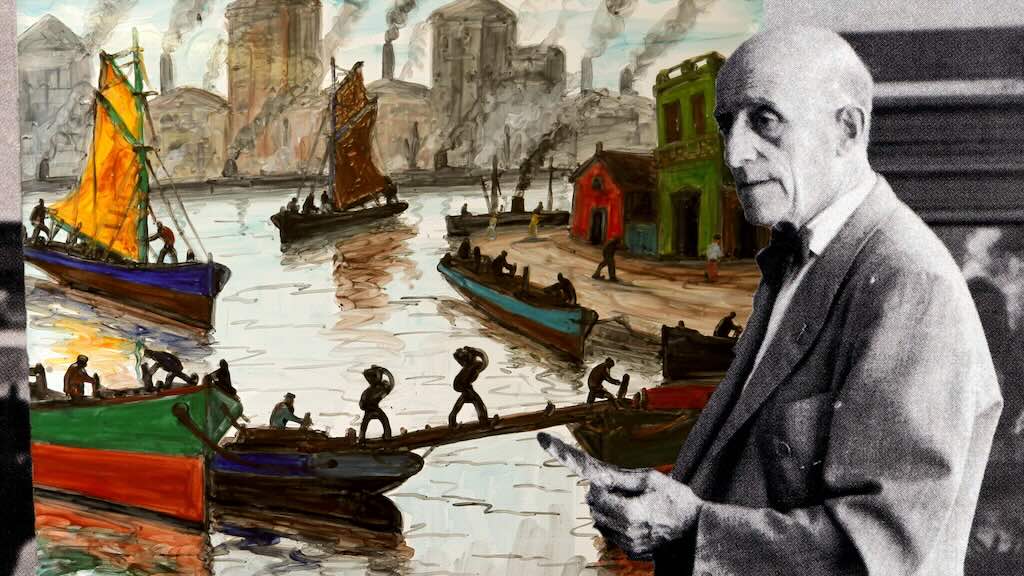

- The artist who painted the soul of La Boca

Visiting Buenos Aires (Part II)

Visiting Buenos Aires (Part III)

In addition check out my visit to the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

This post is also one of a series describing my entire trip, including:-

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 1-7)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 8-11)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 12-17)

- Planning a Cruise to the Antarctic

- My Antarctic Packing List

- Le Lyrial – A Luxury Expedition Cruise Ship

- Le Lyrial – Exploring Hidden Engineering

- Air Dolomiti Embraer E195

- Lufthansa Business Class Lounge, Frankfurt

- Lufthansa Boeing 747-8 – Business Class

- Ministro Pistarini International Airport, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Meliã Recoleta, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Sofitel Recoleta, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Palladio, Buenos Aires

- Lufthansa Boeing 747-8 – First Class

- Lufthansa First Class Lounge, Frankfurt

The "Paris of the South"

This post is about my visit to the charismatic “Paris of the South“

This website produced the above comparison between Buenos Aires and Paris.

Of course I expected to see only a small part of this famous city. However, driving into the city from the airport, I realised that Buenos Aires was not Paris! And it did not help that the 45 km taxi ride from the airport to the city centre took 90 minutes because of the traffic (OK, so it’s a bit like Paris).

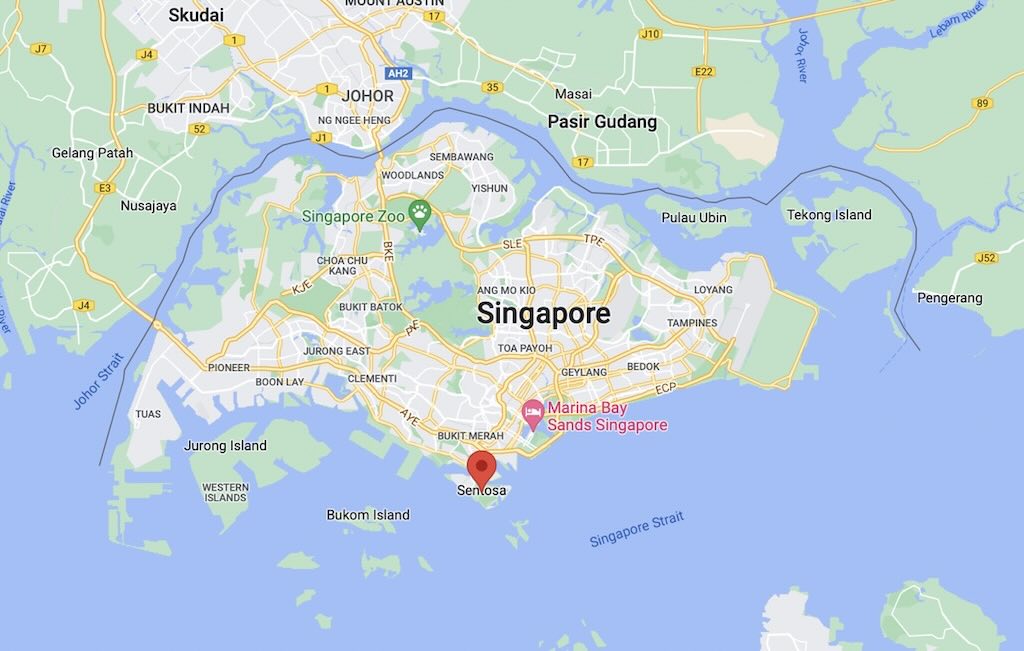

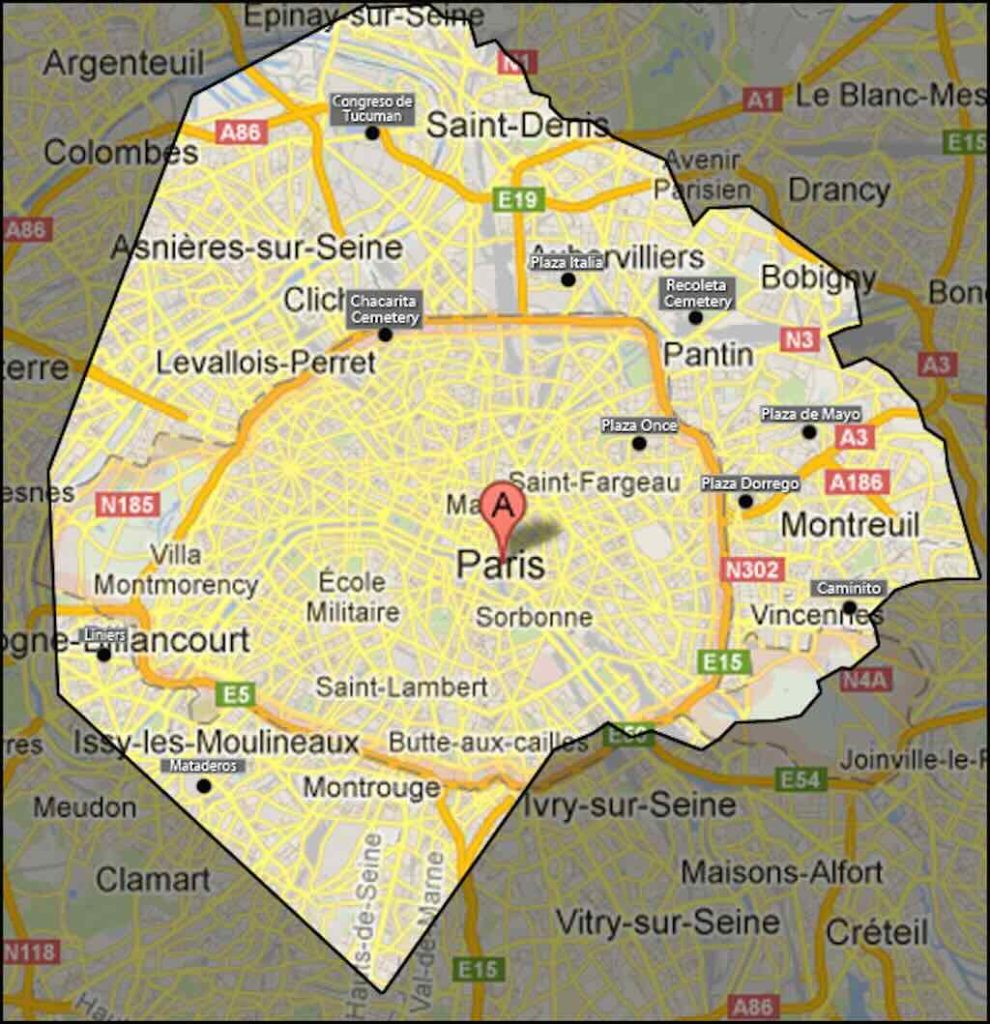

The key difference is that the centre of Paris is quite concentrated (around 100 square kilometres for a population of around 2.1 million), whereas Buenos Aires is spread over 200 square kilometres (with a population of around 3.1 million).

So Notre-Dame cathedral to the Eiffel Tower is about 4.5 km, whereas the distance from San Telmo Market to the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano is nearly 7 km. The first example is quite representative of Paris, whereas the second example only scratches the surface of the city of Buenos Aires. The reality is that the city of Buenos Aires is spread over an area that is twice the size of Paris.

Figures and comparisons vary but Buenos Aires has an average temperature of about 6°C above Paris, a population density around 25% lower than Paris, and a younger population with a slightly lower unemployment rate. Obviously the cost of living is higher in Paris, but so are wages. Most people think that money goes further in Buenos Aires than in Paris, despite rampant inflation.

At the end of the day, the people are different, they live in different places, have different visions of what life is all about, etc.

Someone once said that they came to Buenos Aires with an open mind and left with a full heart.

Yet someone else said visiting Paris was like falling in love with an older woman.

Getting Around the City

As mentioned above, Buenos Aires is a big city, and distances can be deceptive. Let’s take an example. I stayed in the hotel Palladio in an area called Recoleta, a well know barrio or neighbourhood located in the northern part of the city. This is in many ways considered quite “central”, yet the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes was a 25 minute walk in one direction, and the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires was a 40 minute walk in the opposite direction. Not forgetting that walking to museums such as the Museo Histórico Nacional would take more than 70 minutes, and to the Museo Moderno just under 60 minutes.

Of course a taxi/uber is the best option, and as of mid-December 2024 they were 10 time cheaper than the same trip in Paris or New York. In Buenos Aires a 15-minute cab ride cost at worst $3.50 (on a Sunday in light traffic with an ‘F1’ cab driver). Worth every penny. Not sure how an uber could beat that.

I didn’t use public transport, so I can’t comment on that.

Where is Buanos Aries?

Buenos Aires is situated in the southeastern region of South America. It lies on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, an estuary formed by the confluence of the Paraná and Uruguay Rivers. The city faces the Atlantic Ocean to the east and serves as a major port, connecting Argentina to international maritime routes.

The city has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa under the Köppen climate classification), with mild winters and hot, humid summers. Its proximity to the ocean and the vast Pampas plains to the west influences its moderate temperature variations and frequent rainfall.

The Rio de la Plata is one of the widest estuaries in the world, if not the widest, and it’s width (up to 220 km across) creates the illusion of an ocean horizon from the city’s shore, though it’s entirely composed of river (non saline) water.

Buenos Aires has an average elevation of only 25 meters above sea level, making it one of the flattest cities in the world. This also means that it has an extensive navigable river system. For example, the Paraná, one of the longest rivers in South America, is navigable for more than 2,000 km upstream, well into Brazil. On the other hand the Río de la Plata is prone to sudestadas, a unique weather phenomenon involving strong southeast winds that cause the river to swell, resulting in localised flooding in parts of the city.

Buenos Aires is also one of the largest cities in the Southern Hemisphere, and its dense urban environment amplifies the heat retention during the summer months, creating a localised “urban heat island” effect. This contrasts sharply with the cooler, greener surroundings of the Pampas.

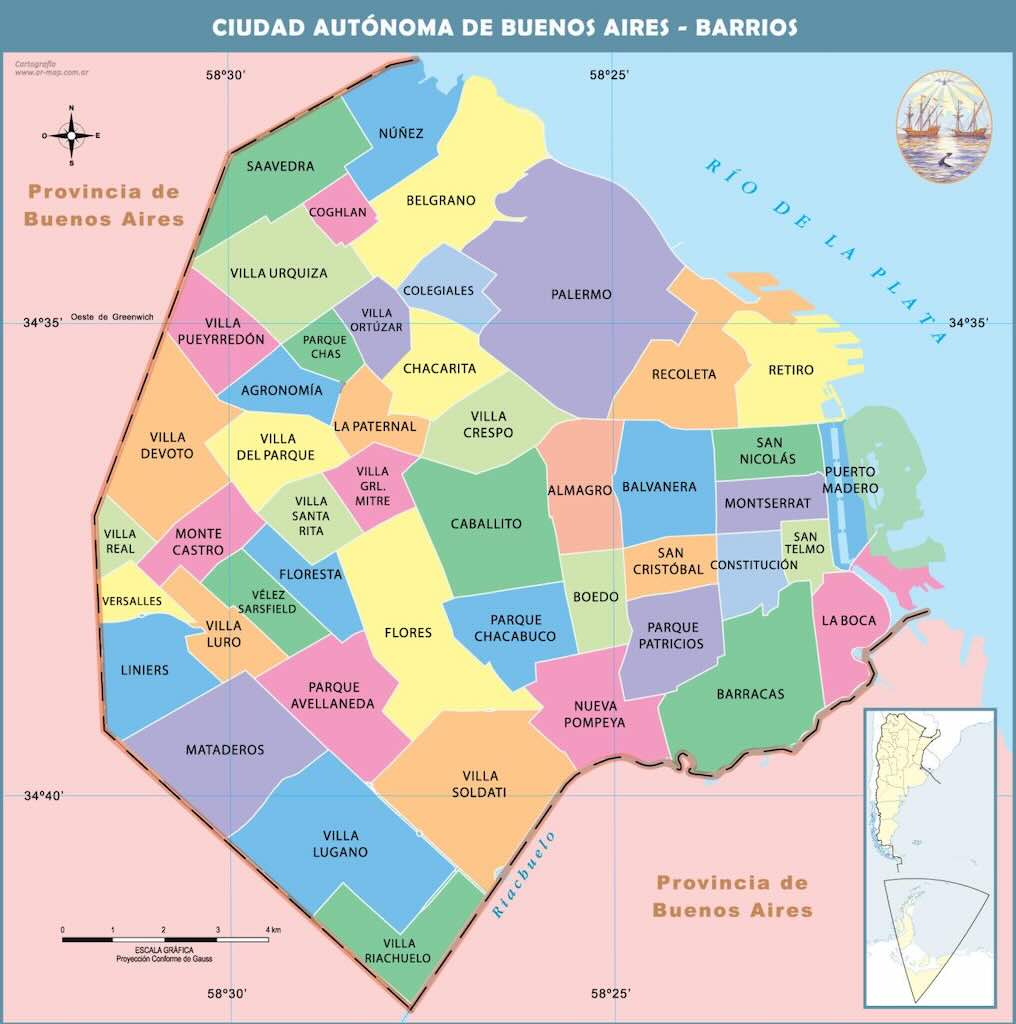

Barrios in Buenos Aires

The City of Buenos Aires (Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, or CABA) is divided into 48 barrios (neighbourhoods). These barrios collectively cover an area of approximately 200 square kilometres and are home to about 3 million residents (that’s around 15,000 people per square kilometre).

The population density of London is only around 6,000 people per square kilometre, Singapore is around 8,500 people per square kilometre, whereas Paris is over 20,000 people per square kilometre, but Manila has the worlds highest population density for a capital city with around 43,000 people per square kilometre.

Do You Know Your Barrios?

Here are a few quiz questions, with the answers at the end of this blog post.

Was barrio Palermo named after a person or place?

Which barrio was named after a railway engineer?

Which barrio was named after the author of the Argentine Civil Code?

Why is there a barrio named Lugano?

Was the barrio Soldati named after soldiers?

Why is there a barrio called Puerto Madero?

and How many barrios are named after someone who donated the land?

Why Compare Buenos Aires to Paris?

The vision to make Buenos Aires the “Paris of South America”, was not just about architecture. In fact, the layout of Buenos Aires was directly shaped by Baron Haussmann’s Parisian urban reforms.

Argentine urban planners literally copied entire sections of the Paris’ street network. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Buenos Aires underwent a massive transformation inspired by Paris. The Diagonal Norte and Diagonal Sur avenues, cutting through the city’s historic center, were designed to mimic Haussmann’s grand diagonal boulevards in Paris.

However unlike Paris, which fully executed Haussmann’s plans, Buenos Aires never completed its diagonal grid. The Argentine government ran out of money and political will, so the city remains a fascinating half-finished version of Haussmann’s Paris.

Urban planning records in Paris’ city archives reference a network of tunnels extending beneath the Louvre, the Palais-Royal, and key government offices, allowing safe evacuation or discreet movement. Other tunnels were built to allow VIPs to move between palaces, government buildings, and private residences without mingling with commoners. Sections of these passages still exist under the Louvre, Palais Royal, and Opéra Garnier, though many have been sealed off.

Buenos Aires, influenced by Parisian urbanism, had its own elite underground tunnel network, built between the 17th and 19th centuries, but actively used until the early 20th century. Under Plaza de Mayo and the Cabildo, there are tunnels once used by Spanish colonial elites to move between government buildings without crossing dangerous streets. And wealthy families in Buenos Aires’ aristocratic neighbourhoods, like San Telmo and Montserrat, built private tunnels to connect their homes to churches, embassies, and government offices. The tunnels under Manzana de las Luces, the Cabildo, and parts of San Telmo have been partially excavated, confirming their existence (see this report).

It’s known that VIP & Government Tunnels in Paris represent 15-30 km, whereas in Buenos Aires they represent 8-15 km. Including total underground infrastructure (catacombs, quarries, and historical tunnels), Paris surpasses 300 km, while Buenos Aires may have 20-30 km of known passages.

But the link between Buenos Aires and Paris goes even deeper.

In the early 20th century, France was Argentina’s second-largest foreign investor (after Great Britain), and many major Argentine banks, railways, and industries were financed by Parisian capital. Business records from French-Argentine banks (like Société Générale’s Argentine branch) reveal concerns about time zone synchronisation in financial transactions. So in 1920, Argentina quietly adjusted its official time zone to GMT-4, which was unnaturally ahead of its solar time. This made Buenos Aires’ clocks run almost exactly in sync with Paris (GMT+1) during parts of the year, despite the cities being on nearly opposite sides of the Atlantic. The time change was never officially described as a Parisian alignment, but Argentine intellectuals at the time openly debated the idea that Buenos Aires should run “on European time” rather than its natural solar time.

Historical newspaper debates from La Nación and La Prensa discussed the cultural and financial motivations behind Buenos Aires keeping “European” hours. Argentina’s Boletín Oficial recorded the time zone decrees from the 1920s and 1930s. By the late 1930s, global standardisation of time zones forced Argentina to gradually shift to GMT-3 and later GMT-3:30 (which persisted until 1969). Today Buenos Aires operates on Argentina Time (ART, UTC-3) year-round and does not observe daylight saving time.

It is said that, as a result of this time zone synchronisation, “porteños“ traditionally ate dinner at Parisian hours (21:00 or later), unlike other Latin American capitals.

Argentina’s elite saw their country as the “Europe of South America” and sought to align Buenos Aires with Paris rather than New York or London. Newspapers, fashion, and even theatrical schedules in Buenos Aires were set to match Parisian norms, reinforcing the city’s European self-image.

For example, in the early 1900s, Buenos Aires’ Teatro Colón was designed to rival the world’s greatest opera houses, including the Palais Garnier in Paris. But what almost no one knows is that the stage machinery of Teatro Colón was built as an almost exact replica of the Paris Opera’s stage system, complete with its trapdoors, rotating platforms, and counterweight mechanisms. The reason was simple, Argentina wanted to attract the biggest European productions, and they copied the Paris Opera’s technology to ensure that entire French and Italian opera sets could be shipped to Buenos Aires and reconstructed seamlessly.

Teatro Colón’s backstage still retains elements of this original 1908 system, and records from its original architects, Francesco Tamburini and Víctor Meano, confirm the Parisian inspiration. Additionally, stage designers who have worked in both the Palais Garnier and Teatro Colón have remarked on their strikingly similar backstage mechanics.

First Impressions

First impressions are important, but they can also be deceiving. No more so as a tourist, given that I spent most of my time in just a few barrios near the river.

Check out the Casa Chorizo, a popular type of dwelling from the late 19th to early 20th century Buenos Aires.

In many neighbourhoods, you’ll find Propiedad Horizontal houses, which are low-rise, shared-lot houses hidden behind unassuming street doors. Behind what looks like a single-family home or a blank wall is often a maze of patios, passageways, and multiple small dwellings.

As with most big cities, they can be very pleasant for those who are wealthy and a nightmare for those who are poor. It’s also true that some places can be great to live in, but not particularly interesting to visit as a tourist.

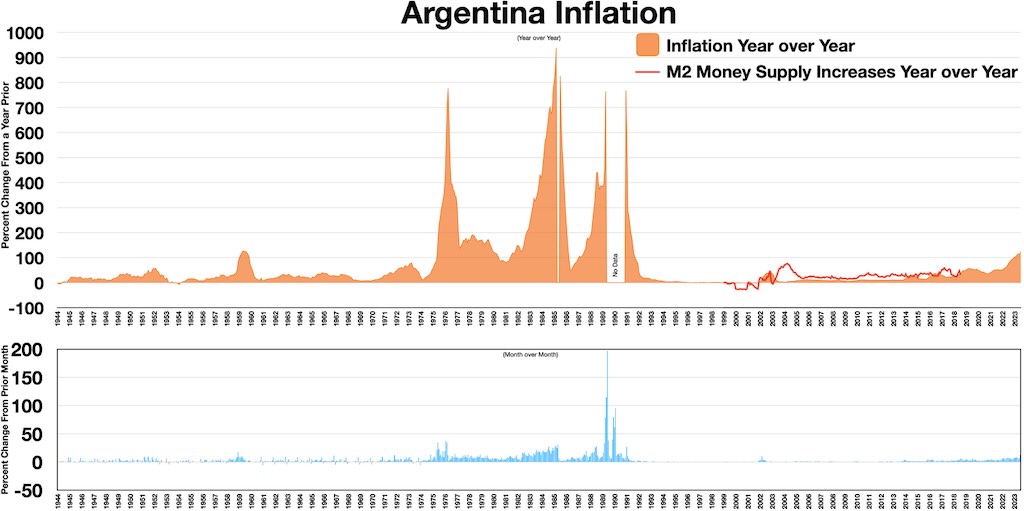

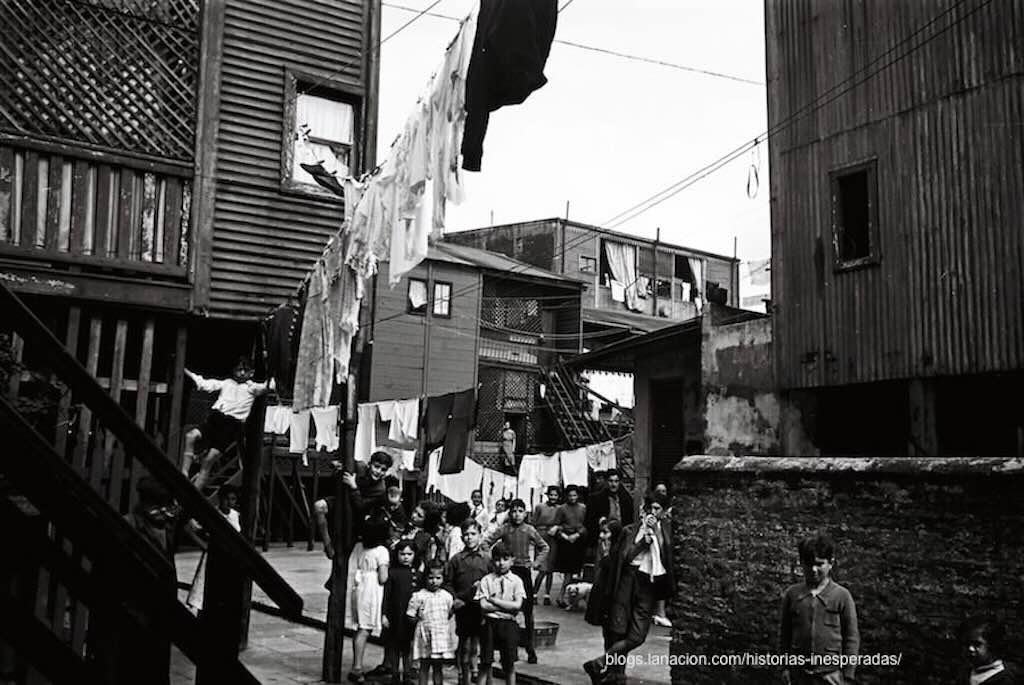

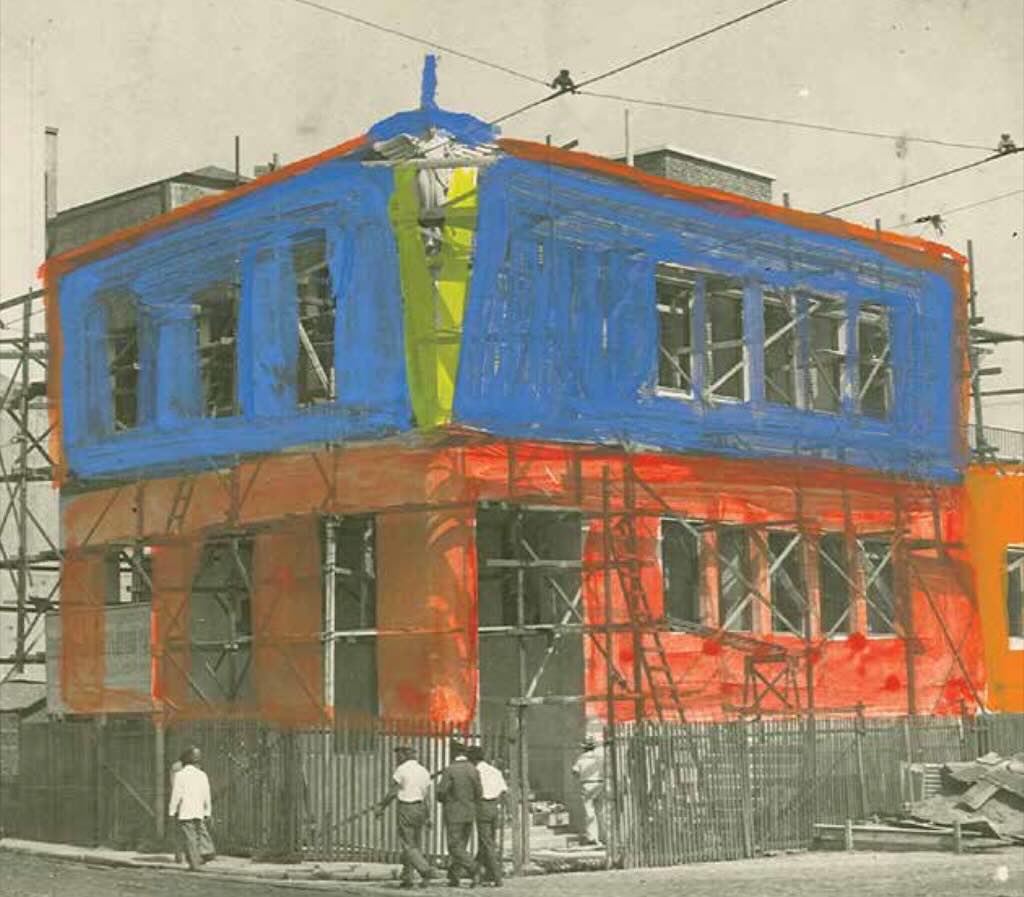

Above we have four different views of Buenos Aires, from the 50s, 70s, 80s, and 2000s. Each represents one facet of present-day life in a big city that has lived through economic crises after crises (see below the inflation statistic for 1944-2023).

But its often wrong to stop with an overly simplistic analysis.

My straw poll was that most people in Buenos Aires were not prepared to comment on the political situation over the last year (2024), but everyone was happy that inflation had gone down.

As of mid-December 2024, the French President Emmanuel Macron’s approval rating was at 22–26%, US President Joe Biden had an approval rating of 37%, and Argentina’s President Javier Milei’s official approval rating was significantly higher, ranging from 61–68% (some people suggested that it was more likely around 50%).

The unemployment rate in Buenos Aires was approximately 7.6% in the second quarter of 2024, the French unemployment rate in late 2024 was 7.1%, and in the US it was around 4.1%. However Buenos Aires has a younger demographic compared to Paris and New York. Approximately 27% of Buenos Aires’ population is under 30, whereas Paris has a slightly older population, with about 21% under 30, and New York in between, with around 23% under 30. Youth unemployment in both Buenos Aires and Paris are a bit over 20%, whereas in New York it’s just under 10%.

Traffic congestion is a problem in New York, Paris and Buenos Aires, but the average traffic congestion index in New York recently stood at nearly 48%, placing it second worst in global rankings, Paris was about the same as Buenos Aires at around 37%. This reflects a number of issues, including the number of hours lost per year in traffic.

According to the 2024 World Happiness Report, France ranked 21st, the US ranked 23rd, and Argentina ranks 56th. However, the French report highlighted urban pressures like cost of living, work stress, and social issues. In the US the report highlighted issues such as economic inequality, mental health issues, and political division that had affected the overall well-being, especially in major urban centers like New York. While for Buenos Aires, the challenges were inflation and economic instability, but despite these issues, Argentinians still reported a sense of community and belonging.

Turning to parks and green spaces, about 16–20% of the total area of Buenos Aires is dedicated to parks, green spaces, and public squares. The equivalent figure for Paris is about 20%, and for New York 14-16%.

Finally if we ask what the man-in-the-street wants, in New York its better law enforcement strategies, expanded shelter programs, and solutions to the root causes of homelessness. In Paris its reforms to reduce rents, more affordable housing, and reducing gentrification. In Buenos Aires its better economic policies, wage stabilisation, and stronger social support systems.

My own personal impressions of Buenos Aires, as a tourist staying in a 5-star hotel and walking around the city centre visiting museums, etc., were quite positive.

Initially I was surprised to see street markets everywhere. Markets that have become “institutionalised”. I spoke to one store holder who said that it would be impossible for them to pay the rent on a shop front, and together with the other stalls in the market they felt that they were an important part of everyday life in the city. I was also surprised in the variety of good quality merchandise on offer, and that there were more Argentines buying, than tourists. The store holder said that she was able to live correctly because her husband worked, but some of the others were living in their cars parked next to the stalls.

Another thing that surprised me was that Buenos Aires still has a “third-world” electrical network even in quite expensive barrios. One taxi drive said he did not care about the power cables, but he didn’t want people digging up the roads.

Argentina drivers appeared disciplined (all except one taxi driver I met who was certain related to Ayrton Senna), and I felt safe on both the roads and pavements. Streets and pavements were very clean (no dog poop), even if some pavement repairs would not go amiss. The parks are beautiful and very well maintained. In my whole stay in the city I only saw litter once, near one of the local hospitals. There were some people sleeping in the parks, etc., but unfortunately this is a truth in every big, and not so big, city. I felt perfectly safe (I did not go out at night), and I found porteños more friendly than New Yorkers or Parisians.

If I had to pick one thing that impressed me the most, it’s the streets lined with beautifully mature trees. Just seeing these shaded streets incited me to walk as much as possible. Despite its size, Buenos Aires is a city that can only really be appreciated when walking.

Barrios - Highs and Lows

The above list more or less defines what are the most expensive barrios. Recoleta costs around $US 2,800–4,000 per square metre, Palermo Solo and Palermo Chico about $US 2,500–3,800, and Belgrano about $US 2,200–3,200. However the most expensive barrio of Buenos Aires is probably Puerto Madero, known for its luxury high-rises, waterfront views, and exclusivity. Prices can range from $US 4,000–6,000 per square metre (or even up to $US 10,000 per square metre).

La Boca - the Odd One Out

Boca Juniors supporters are called los Xeneizes because the name comes from the club’s Genoese immigrant origins in the early 20th century. Boca Juniors was founded in 1905 in the La Boca neighbourhood, an area heavily populated by Italian immigrants, especially from Genoa, Italy. The word Xeneize is a phonetic adaptation of Zeneize, which means “Genoese” in the Ligurian dialect spoken by the immigrants. Boca’s fans continued using Xeneize to emphasise their immigrant, hardworking, and streetwise character.

To be “abonos” to Boca Juniors you need “socio” status (club membership), and they have a waiting list. Or better still a family member could leave their season ticket to you in their will. For non-members or visitors, the most reliable way to see a game is through hospitality packages or guided matchday experiences, that can easily cost between €200–€350 depending on seating, etc.

La Bombonera, officially known as Estadio Alberto J. Armando, is painted in Boca Juniors’ blue and yellow colours, inspired by the Swedish flag. The stadium is squashed into a small space in La Boca, and this has conditioned its unique “D”-like shape. It has three very steep stands surrounding the pitch and a fourth stand that is almost vertical. The capacity is 54,000 and spectators are almost sitting on top of the players, creating a kind of immersive experience.

When architect Viktor Sulčič designed La Bombonera in the late 1930s, he faced a serious space problem. Boca’s land for the stadium was too small to fit a traditional four-sided stadium. To solve this, Sulčič adapted an unusual concept, he borrowed elements from a Croatian theatre he had studied in Europe. The unique vertical grandstands and compact design of La Bombonera were influenced by the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb (Hrvatsko Narodno Kazalište). Both structures share a near-vertical seating arrangement, maximising audience capacity while maintaining an intimate atmosphere. Sulčič, who was of Slovenian-Croatian origin, knew about theatre acoustics and how sound reverberated in small, enclosed spaces, and this helped create La Bombonera’s famous “heartbeat” effect when fans jump in unison.

Why did Boca Juniors adopt the colours on the Swedish flag?

In 1905, Boca Juniors initially wore several different kits. They started with a white jersey with black or blue details, but soon found themselves in a dispute with another local team, Nottingham de Almagro, which also used similar colours. To settle the matter, they agreed that the team that won a match between them would keep the colours, and Boca lost.

Rather than arguing further, Boca decided to adopt new colours in a creative way. Club member Juan Brichetto, who worked at the Buenos Aires port, suggested that they take inspiration from the flag of the first ship that arrived in port the following morning. The next ship that came in was Swedish, so Boca adopted Sweden’s blue and yellow as their official colours. The first blue and yellow kit was introduced in 1907, with a diagonal yellow stripe, but later it was changed to the horizontal band seen today.

And What About River Plate?

For River Plate, the club operates a membership system called Somos River, which is required to access season tickets and attend matches at their stadium, El Monumental. Membership fees for Somos River start at about $US 14 per month. Being a member gives you priority access to purchase tickets, but it does not guarantee a season ticket due to high demand. It’s possible to find seats, but prices depend on the seating section and the match, and can range from €50 minimum to €500 for VIP seating.

When River Plate built El Monumental in the 1930s, the original architectural plans included a full roof covering the entire stadium. The idea was to create a European-style covered stadium, similar to those seen in Italy’s Mussolini-era sports infrastructure, which was a major influence on the architects. However, only three-quarters of the stadium were completed in 1938 due to a lack of funds, and the missing fourth stand (the current Sívori Stand) was delayed indefinitely.

To finance the stadium, River Plate took out a massive loan from the Argentine government, which was backed by European steel imports. However, when World War II broke out in 1939, international trade collapsed, and the European suppliers defaulted, meaning the materials for the roof structure were never delivered. River Plate could not repay the full loan, and the government froze further funding, leaving the stadium unfinished for decades. Most fans assume the stadium was always meant to be open-air.

El Monumental, officially known as Estadio Más Monumental, is located in the barrio Núñez, one of the better areas of Buenos Aires. The stadium is the traditional oval shape with four stands surrounding the pitch, and has a capacity of over 83,000, making it the largest stadium in South America.

River Plate supporters are called Los Millonarios (The Millionaires), not because they come from the richer barrios of the city. Unlike many football club nicknames that come from their playing style or colours, River Plate earned the nickname due to a controversial record-breaking transfer in the 1930s. In 1931, River Plate made a huge, unprecedented transfer by signing Carlos Peucelle from Sportivo Buenos Aires for 10,000 pesos, an astronomical amount at the time (remembering that at that time most players were part-timers). This was one of the first massive transfers in Argentine football history, marking River as a club with financial power. A year later, in 1932, River Plate shattered records again, signing Bernabé Ferreyra from Tigre for 35,000 pesos, an unheard-of sum in world football at the time. Ferreyra’s salary was higher than that of some government ministers, leading rival fans and the media to mock River Plate as los Millonarios.

What would 10,000 pesos be today? You will be surprised. We need to factor in historical inflation within Argentina and the exchange rate between the Argentine peso and the US dollar over time. But there is a problem, tracking the Argentine peso through numerous devaluations and currency changes means that it would today be worth literally nothing. However, at the time 10,000 pesos would have brought someone a nice house in a decent barrio.

Reality check

Both clubs are almost like national institutions, each dominating Argentine and South American football in different ways. Their Superclásico rivalry is one of the most intense in world football, and debates over who is superior will always remain.

Boca has had more international success, and has a passionate fanbase and an intimidating stadium. River Plate has won more league titles (marginally), and has a larger stadium and probably slightly better finances. But they are both “small fry” with annual revenues (2023) of ~$120 to ~$130 million, compared to my team (Spurs) who’s revenue in 2023 was ~£500 million.

Just to complete the history of these two clubs, La Boca was the birthplace of both River Plate (1901) and Boca Juniors (1905). At that time, there was a boom in associationism in the city, from which many football clubs emerged. And membership grew rapidly when Manuel Quintana’s government (1904-1906), violently suppressed several workers’ demonstrations.

The Tragedy of River Plate vs. Boca Juniors – June 23, 1968

On June 23, 1968, during a Superclásico between Boca Juniors and River Plate at the El Monumental, 71 people were killed and over 60 injured in what remains Argentina’s deadliest stadium disaster.

After the match, which ended in a 0-0 draw, a human crush occurred at Gate 12 (Puerta 12) of the stadium. This gate was an exit point used by Boca Juniors fans. As fans tried to leave, they found the exit either closed or partially obstructed. People continued pressing forward, unaware of the blockage. The result was a human pile-up, as those at the front were crushed or suffocated by the weight of the crowd behind them. Most of the victims were teenagers and young adults.

The authorities suggested that fans had been running and crashed into the gate. However, many survivors claimed the gate was locked or partially closed. The reality was that there was no adequate evacuation plan, and many died due to asphyxiation.

The case was never fully resolved, and no one was held criminally responsible.

My thoughts also go out to those killed in the Estadio Nacional Disaster (Peru, 1964), the Hillsborough Disaster (England, 1989), the Ibrox Disaster (Scotland, 1971), and the Luzhniki Disaster (Russia, 1982).

These disasters share common themes of poor stadium infrastructure, inadequate exits, lack of crowd control, and official negligence, often compounded by authorities trying to deflect responsibility.

What to See in Buenos Aires?

Just as important as what to see, is how to see it. I decided to try a typical city but tour, to add two days with a private guide, and finally to focus on some key monuments and a couple of museums.

My private guide was Carlos (carlopezbello@gmail.com) and he was great. What I wanted was to see some sights, but slowly, chatting, taking a coffee, and learning a little about life in Buenos Aires.

I’ve compressed all this into a few photos with comments.

Plaza de Mayo - Resistance and Memory

Let’s start in Plaza de Mayo. The above photo might not be perfect, but it does show the important institutions found in the Plaza. We are looking into the Plaza over the top of the white tower on the Museo Nacional del Cabildo de Buenos Aires y de la Revolución de Mayo. The building with the classical looking twelve columns and the triangular pediment on top is the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Cathedral. It is home to the Mausoleum of General San Martín, nicknamed “the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru”. It was also the place where Jorge Bergoglio (now known as Pope Francis) led mass as Archbishop of Buenos Aires until 2013. In the far corner of the Plaza there is the Banco de la Nación Argentina, and at the far end is the Casa Rosada, the presidents official workplace (its really called Casa de Gobierno).

The Plaza de Mayo was created in 1884, as a result of the union of the Plaza de la Victoria and Plaza del Fuerte, and the demolition of a construction called Recova Vieja. The Recova was called in its time Recova de la Carne (or Meat Market), and was a kind of covered market arcade, composed of two long aligned galleries, symmetrical, compartmentalised, without floors, connected to each other by a monumental central arch. Building began in 1802, and it served, until its demolition in 1883, as the main market of the city. Some experts suggest that the authorisation was for a provisional building, which ended up being built in stone, and lasting 82 years.

In 1880 Buenos Aires was declared the capital city of Argentina, and Torcuato de Alvear served as the first mayor of the city. He had a clear mission to modernise Buenos Aires, and the Recova was the first victim. By 1884 the local press announced “Muere la Recova, nace la Buenos Aires Moderna“.

The Plaza has been the epicentre of Argentine history and politics since its creation in 1580. It was central to the May 1810 events, which led to Argentina’s independence from Spanish rule. On May 25, 1810, residents gathered in front of the Cabildo (the colonial town hall) to demand the resignation of the Spanish viceroy and the establishment of a local government, marking the start of the independence movement.

In October 1945, massive demonstrations in Plaza de Mayo demanded the release of Juan Domingo Perón, then vice president, laying the foundation for his political ascent (17 October was later commemorated as Loyalty Day). Later, Evita Perón (Evita) delivered her famous speeches from the balcony of the Casa Rosada (Presidential Palace), rallying the working classes and advocating for social justice. Evita spoke a heavy populist rhetoric but in a language everyone could understand, always urging the poor to align themselves with Perón’s movement, and in her “Renunciation”, she came across as a selfless woman in line with the Hispanic myth of marianismo.

On June 16, 1955, the Plaza was the site of a violent aerial bombing by sectors of the Argentine military attempting to overthrow Perón. The attack was carried out without warning in the crowded city centre on Thursday, during working hours. Over 300 civilians were killed (including a trolleybus packed with children), marking one of the most tragic events in Argentina’s history.

During the military dictatorship (1976-1983), the Plaza became a symbol of resistance. This period was called the Guerra Sucia (The Dirty War) a name used by the military junta or civic-military dictatorship for its period of state terrorism. The Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, wearing white headscarves, began weekly marches around the Plaza, demanding information about their children who had “disappeared”. This movement remains one of Argentina’s most poignant symbols of human rights advocacy.

More recently the Plaza has hosted numerous protests, including the December 2001 uprising during Argentina’s severe economic crisis. Protesters clashed with police, leading to dozens of deaths and the resignation of President Fernando de la Rúa.

But Plaza de Mayo has also been a site of joy, hosting celebrations for national victories, such as Argentina’s FIFA World Cup wins (1986 and 2022, and not forgetting 1978), where millions gathered to celebrate. And today, Plaza de Mayo remains a key space for political expression, protests, and public events, embodying Argentina’s turbulent history.

Plaza de Mayo has a touch of the Plaza Mayor. Built to reinforce the sense of royal power, Catholic tradition, and civic engagement, today its more to do with political activism, national celebrations, and a bit of cultural heritage. I see this transition as a positive.

Talking with locals its clear that Plaza de Mayo plays an important role in both their personal and collective memories. Which is more than can be said for major squares in London, Paris or New York. Londoners, Parisians and New Yorkers opinions and memories will be less about political protest and more about traffic chaos in Trafalgar Square, Place de l’Étoile, or Time Square.

In Plaza de Mayo there is an equestrian monument to General Manuel Belgrano in front of the Casa Rosada. It depicts General Manuel Belgrano holding the Flag of Argentina, and it is made of bronze over a pedestal of granite.

When I visited Plaza de Mayo on the 23 November 2024 there were a multitude of stones, etc. all marked with the name of someone who died of COVID, often with dates. I understand that Argentina lost more than 100,000 people to COVID. In August 2021, hundreds of their family members and friends marched to protest against the government’s handling of the pandemic. They placed the stones around the statue, creating a new memorial that’s was later protected by a glass barrier.

Also in Plaza de Mayo there is another recent memorial. It’s to the mothers who led a peaceful resistance movement against the military dictatorship that “disappeared” their children. The memorial is centred on the Pirámide de Mayo now located at the hub of the Plaza de Mayo. The pyramid dates from sometime shortly after 1811 and is the oldest national monument in the city, but no one knows why they decided for a pyramid. In 2005 it was declared a “Historic Site”, and currently on the radial lines there are stylised images of the white scarves that the mothers of the victims wore on their heads to identify themselves.

The Casa Rosada was originally a Spanish fort built in 1580. After Argentina gained independence, the building was used as a customs house. In 1862, President Bartolomé Mitre chose it to be the seat of the Argentine government, and he expanded the building and added gardens and wrought-iron grillwork.

There are a few suggestions as to why it is pink, firstly its possible that the colour symbolised peace between the country’s two opposing political parties, the Federals and the Unitarians (the Federals used red, while the Unitarians used white). Another suggestion is that the building may have been painted with a mixture of white paint and cow’s blood to prevent the paint from peeling in the humidity (this was a common practice in the late 19th century).

The Casa Rosada, has gone through a number of transformations reflecting the evolving political and social landscape of Argentina.

In 1594 the site originally was home to the Fort of Juan Baltazar of Austria, constructed by Captain Juan de Garay. In 1713 the Castle of San Miguel replaced the original fort. Then in 1859 the building became a Customs House designed by British Argentine architect Edward Taylor. At the time this Italianate customs building became Buenos Aires’ largest building. In 1873 a Post Office Building was commissioned by President Domingo Sarmiento on the land next to the existing Custom House. It was designed by Swedish Argentine architect Carl Kihlberg. With this change of function, the site acquired French Second Empire architectural elements.

During the period 1882–1898, President Julio Roca initiated the integration of the existing buildings. Architect Enrique Aberg designed a new government house mirroring the post office, and Francesco Tamburini unified the structures with a central Italianate archway, completing the Casa Rosada as known today.

The above view is in fact the “back side” of Casa Rosada dating to 1910, with steps and gardens that are now occupied by Av. La Rábida and Av. Ing. Huergo.

The last change dates from 1938, and was the demolition of the south wing, resulting in the building’s current asymmetrical appearance.

Every day seven grenadiers leave the Casa Rosada and march 284 metres to the Cathedral, where they relieve two grenadiers and return to the seat of Government (no one knows why seven and not six or eight).

This change of the guard takes place at odd hours between 07:00 and 17:00. These grenadiers belong to the two foot squadrons, Chacabuco and Ayacucho, which provide the presidential security at Government House, the custody of the remains of the ‘Liberator’ (General José de San Martín) in the mausoleum at the Metropolitan Cathedral, and the hoisting and lowering of the National Flag at the Plaza de Mayo. In addition they participate in all ceremonial acts carried out at the Casa Rosada and the Cathedral.

Chacabuco and Ayacucho are named after famous battles, and victories. The first was the Battle of Chacabuco (February 12, 1817), a key victory of San Martín’s Army of the Andes over Spanish royalist forces in Chile. A battle that marked the beginning of the liberation of Chile from Spanish rule. The second was the Battle of Ayacucho (December 9, 1824) that took place in Peru. This battle sealed the independence of South America from Spanish rule.

I personally was very disappointed in the lack of respect give to the mausoleum of General José de San Martín. Rather than stop for a moment to look at the black sarcophagus guarded by three life-size female figures that represent Argentina, Chile and Peru, and contemplate the blood shed in freeing those regions from Spains rule, tourists just spent 10 seconds to posed and take selfies.

I was struck by the symbolism of one small plaque, with Maipú on it. What caught my attention was that “mai più” in Italian means “never again”, a very poignant reminder of the stupidity of war. Maipú actually refers to a battle fought near Santiago, Chile on 1818, between South American rebels and Spanish royalists, during the Chilean War of Independence.

In the modern-day photo of Plaza de Mayo we were looking over the top of El Cabildo, which after the May Revolution in 1810, served as seat for the congressmen that established the first Argentine government. Here above, we are looking at the Cabildo, before it was dramatically modified and almost totally rebuilt.

We tend to forget that the term Cabildo comes from the Latin “Capitulum” meaning heads. And the word was adopted by the medieval town halls that existed in Spain, and which took the form of the “Cathedral Councils” that still exist today in some cathedrals. It was the municipal body through which the residents watched over the judicial, administrative, economic and military problems of the municipality.

The Cabildo was not unique, the viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata had cabildos in the cities of Buenos Aires, Salta, Santa Fe, San Luis, Canelones (currently in Uruguay), Corrientes, Luján, Humahuaca, Tilcara, Mendoza, Tucumán, Córdoba, Jujuy, Tarija, Sucre and Potosí (the last three currently in Bolivia). They were composed of councillors, mayors, chief constable, executors of royal orders, procurators, royal scribes, a treasurer, accountant and, of course, a doorman. So what you would not call normal “residents” in today’s sense of the word.

The problem is that what we see today has little to do with the frst historic building finished in 1610. The building also served as a prison, and as has always been the case with prisons, it rapidly became too small. A new building was needed, but only in 1764 did they managed to finish it, and this building then served as the first home for the Argentina government (1810).

I’m not sure about the symbolism of Argentina’s first independent government sitting in a new prison. Perhaps it was used because it was easier to defend from the “will of the people”.

After 1821 the building became a set of offices, and by 1880 the architect Pedro Benoit had completed another total renovation that included the elevation of a tower (ten meters) and the construction of a tiled dome (it was the clock tower that gave the official time in Argentina). Colonial red tiles were removed from the roof while the balconies were decorated with balustrades. The entire facade was refurbished to copy an Italian style. It’s more or less what we see in the above photo.

Then in 1889, with the opening of Avenida de Mayo, three arches on the north side of the building were demolished, and the tower built by Benoit was also demolished alleging that its excessive weight endangered the stability of the construction. This was a period when Buenos Aires, the “big village”, saw itself as the new Paris, and everything had to look French or Italian. Everywhere in South America traditional buildings were too simple and didn’t correspond to the national ambitions of the new world.

In this way the building lost its frontal symmetry, until 1931, when the other three arches on the south side were demolished to harmonise the symmetry of the building. So only five of the original arches remained. In 1933 the Cabildo was declared National Historic Monument. Between 1939 and 1940, the architect Mario Buschiazzo reconstructed the colonial features of the Cabildo using various original documents. The tower, the red tiles, the iron bars on the windows and the wooden windows and doors were all reinstalled, using replicas. And since 1940 the building is often presented as original, when in fact the only thing original is its location (see below).

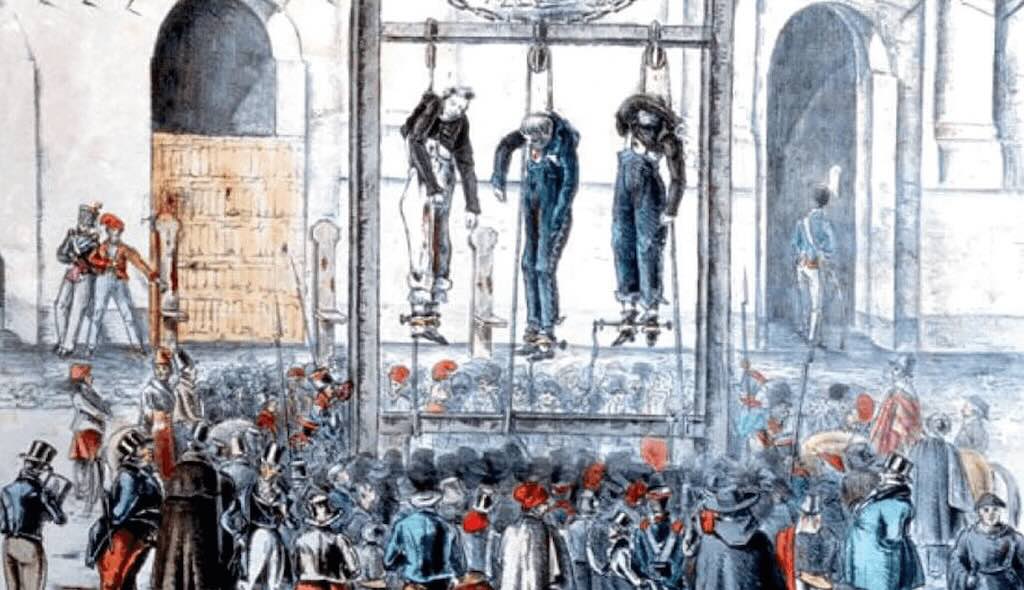

Public plazas, squares, etc. appear to be places that mix public protest with public executions. In Buenos Aires they followed Spanish colonial practices, and public executions served as both punishment and deterrence. The Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata sanctioned capital punishment for severe offences such as murder, heresy, and rebellion, but equally for some important cases of robbery. Executions were often public events intended to reinforce social order and deter criminal behaviour.

From the 1600s it would appear that there were several public executions in Plaza de Mayo (previously just called Plaza Mayor and for a period Plaza de la Victoria). Criminals could be hanged, decapitated, burnt at the stake, garrotted, dismembered, and their bodies displayed as a warning or to deter future dissent.

The first robbery by burglars recorded in Buenos Aires dates back to September 16, 1631. It was at the Casa Rosada, which was the fort of Buenos Aires at that time. One morning they discovered that a cedar chest containing the fort’s funds had been stolen. The search for the culprits did not last long, and soon after, the absence of a certain Pedro Cajal, a 22-year-old Chilean who lived near the Santo Domingo convent, was detected. Days later he was arrested, hidden among bales in a cart with part of the loot.

He was taken to Buenos Aires where he was sentenced to hanging. Cajal protested and asked to die from a blow to the neck with a club and then be decapitated. He could ask for this since he was the natural son of an official in Chile and his request was accepted. On September 30, 1631, he was taken with his servant in shackles to the area of the fort wall so that the people could see his execution. Cajal was killed by a blow from a club and Juan Puma, his servant, was hanged. Their heads were then cut off and displayed on pikes on one of the walls.

Naturally there were other executions in Buenos Aires, but the evidence that they occurred in public in Plaza de Mayo is often circumstantial.

It is my understanding that the axe and the guillotine were never used, and initially the most frequent method was the gallows.

At the end of 1754 the Buenos Aires City Council acquired the so-called “lathe device”, made by the master blacksmith Juan Bautista Dumison, in the hope of alleviating the unnecessary prolongation of suffering for the hanged. But the reality was that any type of garrote caused tremendous suffering to the condemned. The minutes of the City Council said that the instrument existing at that time was “defective” because it was too “narrow” for necks in general, and could not be “accommodated” without causing “serious discomfort”. I’m not sure how you can avoid serious discomfort when garrotting someone!

In Spain, from 1832 onwards, the garrote replaced the gallows as the usual form of execution. King Ferdinand VII had decreed the abolition of hanging and the uniform adoption of the garrote procedure for reasons of “humanity” and “decency”. He added at the time that his “munificent decision” coincided with the “happy birthday of my very beloved wife the queen”. A curious way to celebrate a birthday.

As for the word “garrote”, it literally alluded at first to the wooden stick with which low-class convicts were beaten, that is, to “garrotazos”. Over time, the word persisted in the designation of the new lethal instrument, which should rather be called a lathe or screw.

There were three types of punishment by garrote, depending on the seriousness of the crime. First, the ordinary garrote for the common people, then the noble garrote for the nobles, and finally the vile garrote for infamous crimes. In this last type, as a very visible mockery, the condemned man was dragged to the scaffold or arrived mounted on a donkey, but facing its tail.

It’s worth remembering that the last Viceroy of the Río de la Plata (1810–1811), General Francisco Javier de Elío, was later accused of being an absolutist, and was executed by this means in Valencia, in 1822.

In Buenos Aires, executions were carried out according to a precise and very visible ceremony. They were well staged in specific places in the city where crowds could gather. It was a form of performative spectacle, as morbid as the Roman circus and, at the same time, explicitly disciplinary.

The Mutiny of the Braids (El Motín de las Trenzas) was a military uprising that took place in Buenos Aires on December 6-7, 1811, in which the soldiers and non-commissioned officers of the Regimiento de Patricios refused to obey some orders of the government at that time exercised by the First Triumvirate. Among these was the order to cut the troops’ ponytails-braids (cortar las coletas de las tropas), a sign of distinction and autonomy of the members of that regiment.

On 11 December 1811, a few days after the mutiny was over, four sergeants, two corporals and four soldiers of the Regiment of Patricios were sentenced to death as its ringleaders, shot and hanged in public.

On July 6, 1812, Martín de Álzaga, and more than 30 of his co-conspirators, were executed for mutiny, and their bodies were displayed publicly in Plaza de la Victoria for three days as a deterrent to others. They had been accused of, and condemned for, conspiring to overthrow the First Triumvirate (1811-1812).

In the early hours of April 9, 1814, after a process that lasted barely 30 hours, a certain Captain Marcos Ubeda was summarily executed, and his corpse, in accordance with custom, was exhibited in the Plaza de la Victoria.

Carlos María de Alvear had been a leader of the constituent Assembly of the year 1813 and, goaded by political ambition, succeeded in establishing a Unitarian (centralising) form of government. He would become the Supreme Director of the Second Triumvirate (1812-1814). His form of military dictatorship inevitably included censorship, espionage, denunciation, interception of correspondence, elimination of opponents, etc.

The end of Ubeda, although he was not a high-ranking officer or an influential soldier, brought unsuspected political consequences. He was appreciated by the people, and might one day have caused the collapse of the government. So Alvear thought to take advantage of the quietness of Easter Sunday. However the gallows had been erected almost in front of the cathedral, and the devout people of Buenos Aires could not repress their horror at the spectacle. Even the priest Julián Navarro, who served as curate of San Isidro, was arrested during lunch by order of Alvear, for having expressed his rejection of the arbitrary execution. Inevitably Alvear would later resign, and go into exile in Rio de Janeiro until 1818.

On September 20, 1828, the Buenos Aires newspaper British Packet reported in detail the execution of Jaime Marcet and Juan Pablo Arriaga, carried out in the Plazoleta del Fuerte (part of the future Plaza de Mayo) four days earlier. They were accused of murdering Francisco Álvarez. They were allowed to say goodbye to family, then seated and shot. As required by the punitive protocol, the bodies were taken to the gallows that were erected on a scaffold in front of the house where the murder victim lived. They were held up with ropes passed under their armpits, and remained there like pendulums in the sun for an hour.

On March 6, 1830, the British Packet again reported on the execution, three days earlier, in the same square, of a prisoner named Henri Fleury, accused of forging bank notes in complicity with others. Since ancient times, counterfeiters of currency were executed with great rigour. It was said that in the Middle Ages, in some countries, forgers were boiled alive or had molten lead poured down their throats. Dante Alighieri placed them in one of the pits of the eighth infernal circle, condemned to dropsy that monstrously deformed their bodies.

A wooden scaffold was erected early in the morning in front of the Fort to stage the execution and subsequent hanging of the corpse on the gallows. Before the execution a bonfire was lit in front of the scaffold. It was a substantial part of the ritual, because in that fire, one by one, the counterfeit banknotes were burned. When the fire was consumed, he sat on a wooden bench near the pit, and as he was shot a band began to play. He was then hung on the gallows already prepared.

On October 25, 1837, the death sentence was carried out on two of the four brothers originally called Queenfaith, but renamed in Spanish as Reinafé (a third had already died in prison and the fourth had escaped arrest by crossing to the other side of the Plata). José Vicente Reynafé was an Argentine military man and politician, who served as governor of Córdoba between 1831 and 1835. He was accused and condemned, along with his brothers Francisco, Guillermo and José Antonio Reynafé, for the murder of Facundo Quiroga. A certain Captain Santos Pérez was also accused, and finally the three were shot.

Their bodies hung from a gallows in front of the Cabildo for several hours, as depicted in a striking lithograph of the time (seen above).

On August 18, 1848, Camila O’Gorman, a 23-year-old socialite, and Father Ladislao Gutiérrez were executed by firing squad for their illicit relationship, which was considered scandalous at the time. For the government, the crime was extremely serious in the light of civil and ecclesiastical laws (seduction of a maiden in the case of the priest, and sacrilegious union by both). A commission of jurists issued a categorical ruling in favour of the most severe punishment. Despite O’Gorman being eight months pregnant, Governor Juan Manuel de Rosas ordered their execution to uphold moral standards.

More generally, once the bodies were no longer on display, they were taken to their burial place. Some were even dragged by horses. As there were no public cemeteries yet, the upper class were buried in churches, and the poor in vacant lots. One of the lots was called Rincón de Ánimas, and it’s where the Banco Nación currently stands on the Plaza. Over time it became known as the “Hueco de las Ánimas” or “Hole of the Souls”. This area became associated with local superstitions and ghost stories, and people believed it to be a gathering place for supernatural spirits. The site remained infamous until the construction of the first Teatro Colón in 1857-1888, which led to the disappearance of the “Hueco“.

Plaza de Mayo: A Symbol of Death? Or of Rebirth?

Plaza de Mayo is soaked in history, its cobblestones echo with the footsteps of revolutionaries, dictators, mothers in mourning, and the restless pulse of a nation. It is a place where power is challenged, blood has been spilled, and ghosts linger in the shadow of the Casa Rosada. Death is woven into its fabric, but so is something else, something more enduring.

A stage for tragedy

Death has visited Plaza de Mayo many times. In 1955, the Argentine Air Force dropped bombs on its own people, trying to erase Juan Perón with fire and shrapnel. Over 300 lay dead, their bodies scattered among the wreckage of cars and torn-up pavement. Decades later, in 2001, economic collapse drove the desperate into the streets, and government forces opened fire once more. Again, death marked the Plaza.

And then there are the “disappeared”, the 30,000 souls lost to the military dictatorship (1976–1983). Their names were never written on graves, their bodies never returned to their mothers. But every Thursday, exactly at 15:30, those mothers still march in silent defiance, their white headscarves a living memorial. The Plaza carries their grief, but also their resistance.

A place where death fails to win

If Plaza de Mayo were only a tomb, it would be a cautionary tale. But it is also a cradle of revolution. It was here, in 1810, that Argentina first declared its independence, breaking away from Spain’s grip. It was here that Juan and Eva Perón stood before a sea of people, promising a new Argentina. It was here that the people, time and again, have torn down governments, marched for justice, and demanded to be heard.

Death may stain the Plaza, but it has never silenced it. Instead, the dead become part of its story, their memory fueling the next uprising, the next cry for justice. The Plaza is both a cemetery and a birthplace, a place where history is buried and reborn, over and over again.

A symbol of death? No. A symbol of immortality.

To call Plaza de Mayo a symbol of death is only half the truth. Yes, it has witnessed slaughter, loss, and betrayal. But it has also been the backdrop for resistance, rebirth, and revolution. The dead are not forgotten here, they whisper in the chants of protestors, in the white scarves of the mothers, in the thunder of marching feet.

Death comes to Plaza de Mayo, but it never stays.

La Boca - a Barrio of Resilience and Identity

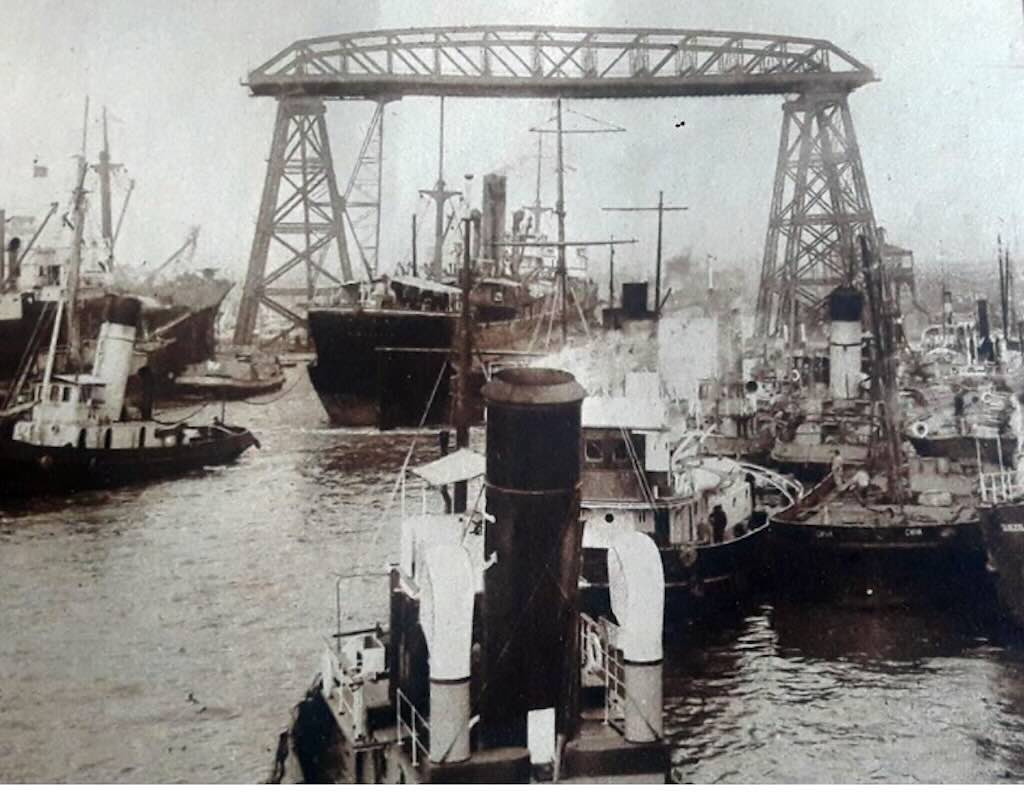

Above we are standing near Calle Caminito, looking over a small bay on the Matanza River, and towards the Puente Transbordador Nicolás Avellaneda. This small bay is probably at the origin of the name La Boca which simply means “the Mouth”.

However, some sources mention that in 1635 a certain Antonio Rocha was listed as the owner of the Riachuelo bend, which later bears his name. In any case La Boca was officially established as its name with the creation of the Justice of the Peace Court (Juzgado de Paz) on August 23, 1870.

Just behind we can see the red bridge Puente Nicolás Avellaneda, which is a unique combination of a drawbridge and a transporter bridge (un tablero levadizo y un puente transbordador). It was designed to replace the older grey Nicolás Avellaneda Transporter Bridge (Nicolás Avellaneda was President of Argentina from 1874 to 1880).

In the photo, we can’t really see it, but just behind is the road bridge Puente del Riachuelo of the Autopista Doctor Ricardo Balbín. This is the official name for the Ruta Nacional 1, which links Buenos Aires with the city of La Plata, capital of the Buenos Aires province.

This oldest grey bridge is one of the most important icons of the La Boca neighbourhood. Built entirely of bolted iron it was inaugurated in 1913, and transported people from one bank of the Matanza-Riachuelo River to the other. At the same time the meandering of the river was altered by a series of dredging and channeling works improving the navigation on the river by large vessels. This extended the port operations area beyond the mouth of the Riachuelo, and into the city. This meant that the existing bridges had to be removed and replaced by other bridges equipped with mobile mechanisms to allow both people to cross and the passage of larger ships.

Originally they thought of a drawbridge, but that meant putting a pillar in the middle of the river, so they acquired a metal superstructure from an English company. What emerged was a 77.5 meter long bridge that could be lifted up to about 43 meters to allow ships to pass. It looks quite massive because being made of low-resistant iron, a high safety coefficient was needed. On the other hand it was particularly modern for the time since it used a 50 HP electric motor to lift the bridge.

It was deactivated in 1947, and there was a plan to dismantle it, but today it is a Argentinian National Monument and one of the last eight transporter bridges still standing in the world, as well as the only one on the American continent. Originally it helped 17,000 workers move from one side of the river to the other side, and since 2017 it has been restored and I think it’s open again as a tourist attraction.

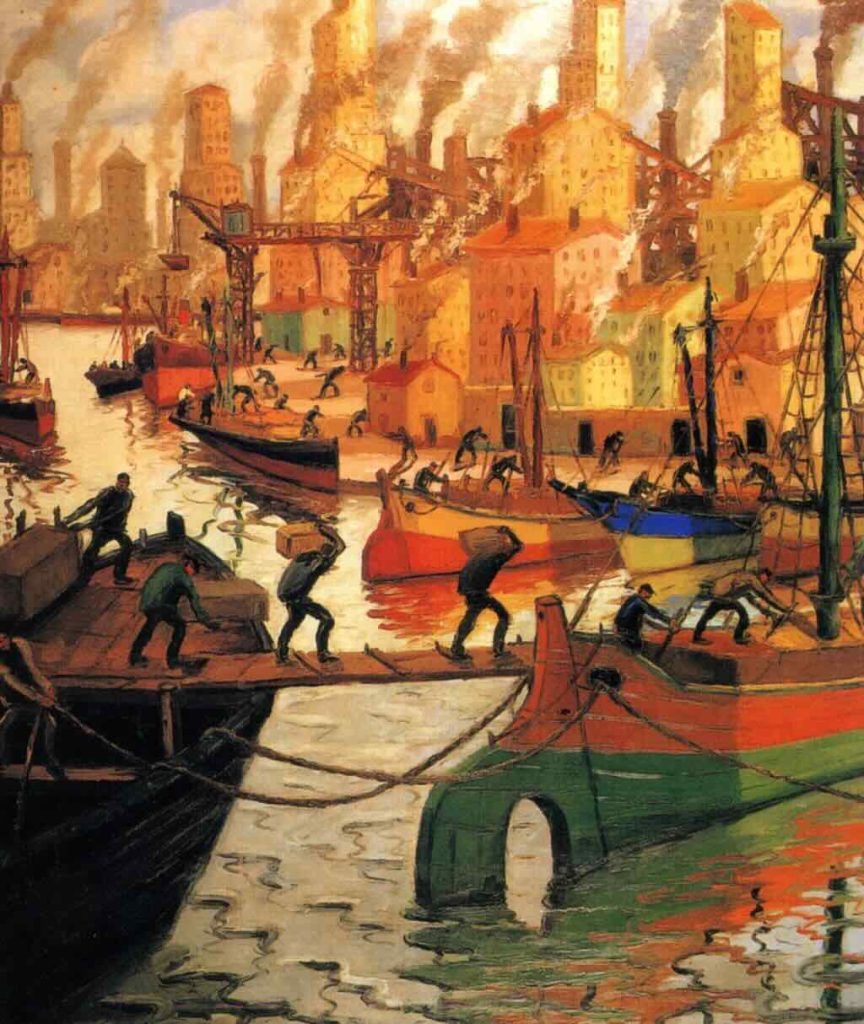

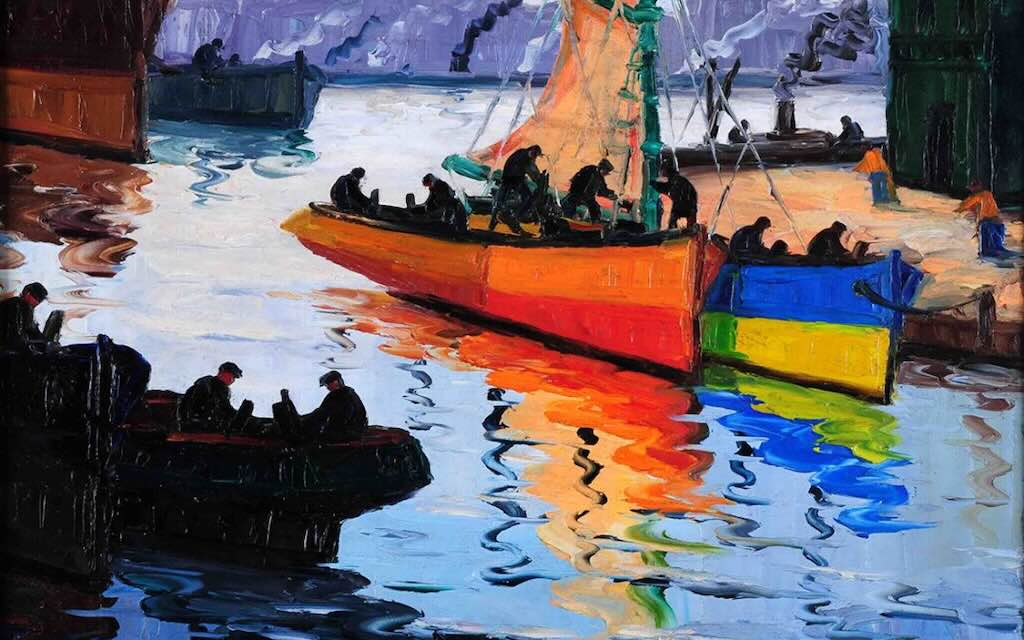

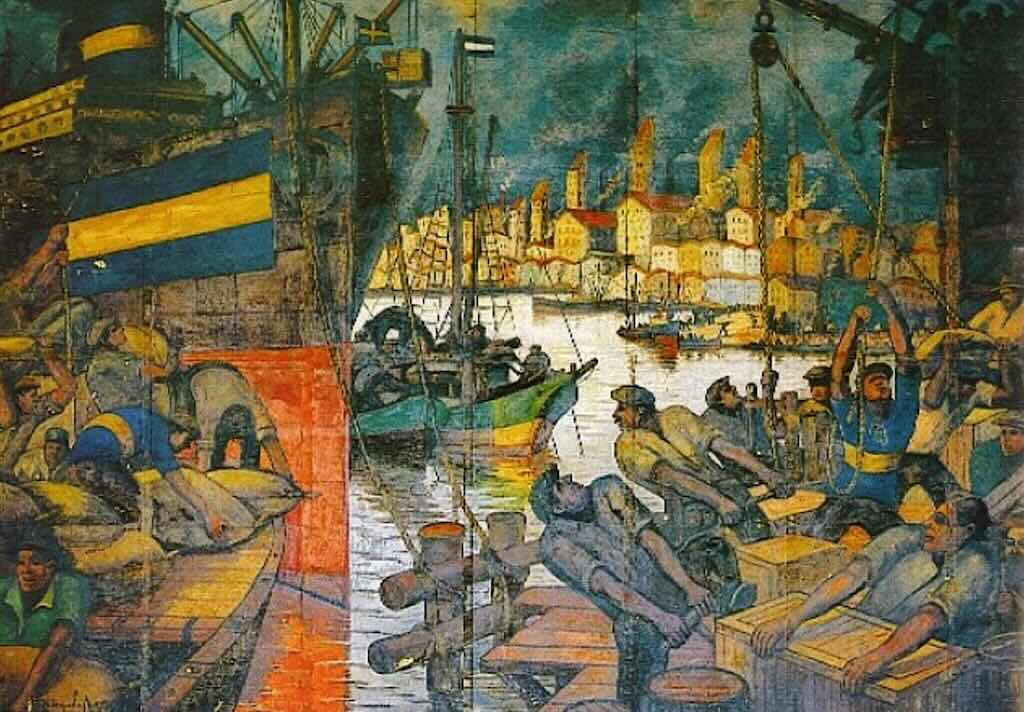

It can’t be considered an aesthetic construction, but as the area became populated with Italian immigrants, many from Genova, the Puente Transbordador was adopted by local painters and engravers because it provided “perspective informations”. The bridge and the landscape of the port became the protagonists of a school of painting arising from those Italian workers living in the neighbourhood of La Boca. Throughout the first decades of the 20th century it was the only tradition of painters focussed on the City of Buenos Aires. Benito Quinquela Martín’s landscapes were full of boats, saturated with colour and populated by countless workers.

La Boca is Not Just Calle Caminito

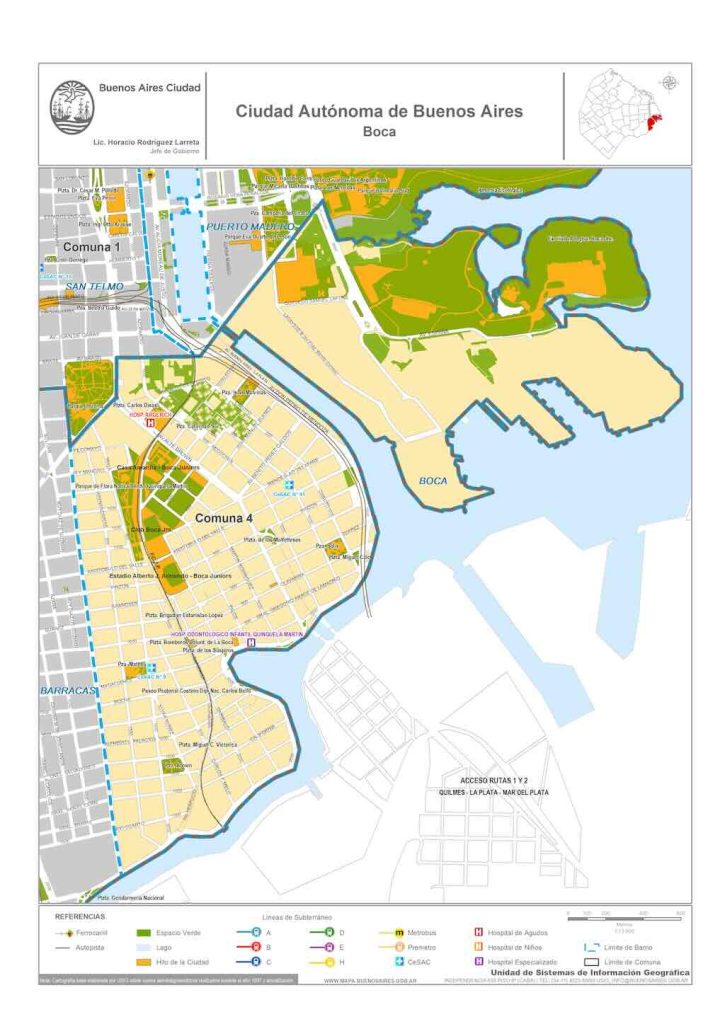

La Boca covers an area of approximately 3.3 square kilometres, and is home to about 43,000 residents, making it one of the smaller yet densely populated barrios in Buenos Aires.

It’s bordered by the Riachuelo River (South & East, separating it from Dock Sud and Avellaneda), by Av. Regimiento de Patricios (West, separating it from Barracas), and by railway tracks & Av. Brasil (North, marking its boundary with San Telmo and Puerto Madero).

As a reminder with Río Matanza-Riachuelo, the Río Matanza refers to the entire river from its source in the Buenos Aires Province to its mouth at the Río de la Plata. However, Río Riachuelo is the name used for the lower section of the river, particularly the last stretch that runs through Buenos Aires and flows into the Río de la Plata at the La Boca.

While Caminito and the Boca Juniors stadium (La Bombonera) attract visitors, the rest of La Boca is largely working-class with high-density poor-quality housing, warehouses, and industrial remnants. Housing is mostly ‘informal’ or old tenement-style dwellings (conventillos), and coloured paint can’t hide the barrios poverty and social issues. The barrios industrial legacy is everywhere, with the former dockyards, metalworking shops, and small factories, many now abandoned or in decline. And the moment you step away from the tourist areas and go further south or west the crime rate increases.

To the east, Av. España which runs parallel to the Riachuelo, separates the urban core of La Boca from the old port and industrial areas. This is an area that mixes storage depots and abandoned industrial lots with a small reclaimed wetland area on the riverbank. The southern part of Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur is actually in La Boca, but access is usually in the barrio Puerto Madero.

Across the Matanza River, south of La Boca, is Puerto Piojo an informal fishing and boating area, used by locals. And the industrial hub Dock Sud, part of Avellaneda, is home to refineries, shipping yards, and container terminals.

The Matanza River (part of the Matanza-Riachuelo system) flows through Buenos Aires Province, passing high-density industrial zones (e.g. Avellaneda, Lanús, and La Matanza) and informal settlements. It is heavily polluted from tanneries, metalworks, and chemical plants. The river has high toxicity, with heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and organic waste, making it one of the most polluted urban waterways in the world. This has created in the river valley severe socio-environmental issues, including poverty, disease, and lack of clean water access. There is an agency trying to manage cleanup and regeneration, but everyone I talked to said it was corrupt and inefficient. One person said that that they were “polishing the doorknobs, whilst the roof was falling in”. In some areas of La Boca residents gave up polishing doorknobs years ago.

The Matanza-Riachuelo River is a 80 km long watercourse that originates in the province of Buenos Aires, forms the southern boundary of the city of Buenos Aires and flows into the Río de la Plata. It is known as Matanza for most of its length and as Riachuelo after crossing General Paz Avenue. It is often designated by both names.

What’s so important about a small river just 80 km long?

Well, its catchment area of over 2,000 square-kilometres is home to about 6 million people, or around 7% of the Argentinian population. And today it’s still treated like a sewer and open-air dump. Comparisons are made between the regulations applied in Argentina against those in Brazil and Uruguay. Either Argentina has no limits to certain discharge activities, or the limits are significantly higher than their neighbours. And this is for discharging ammoniacal nitrogen (animal waste), phosphorus, detergents, phenols (different types of acids), mercury, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, cyanide and lead – just to name a few. Cleanup has being on-going for years, but with limited or no progress given that regulations are poor and often not enforced. Let’s be kind and say “work in progress”.

The Bridges Over the Río Riachuelo

Defining the Río Matanza-Riachuelo as part of the city limit, implied that it was a significant natural barrier. And this is still the case today. The history of each bridge over the Riachuelo, is really a socio-economic history of Argentina.

The Gálvez Bridge, inaugurated on December 1, 1791, was the first to span the river. Constructed primarily of wood due to material shortages, it was overseen by a certain Juan Gutiérrez Gálvez and facilitated vital transportation along the Camino Real al Sud (connecting Buenos Aires to modern-day Bolivia and Peru during the colonial era). Over time, it earned various names, including “Puente de Madera” and “Puente de Barracas“. The bridge suffered damage during the British invasions of 1806 and after numerous and expensive repairs, was ultimately destroyed by a flood in 1858.

Following the destruction of the Gálvez Bridge, Prilidiano Pueyrredón, an accomplished artist and engineer, proposed constructing an iron swing bridge to replace it. Despite initial setbacks, including a collapse during the inaugural attempt in 1867, a new bridge was successfully completed in 1871 and named in Pueyrredón’s honour. This bridge, however, was destroyed by a flood in 1884. Subsequent iterations included a provisional wooden bridge and an iron bascule bridge inaugurated in 1903, which operated until 1931.

On September 20, 1931, a new bascule bridge, also named Pueyrredón, was inaugurated to accommodate increasing traffic. Due to the growing volume of vehicles, the bascule mechanism was decommissioned in 1969. That same year, on December 19, the New Pueyrredón Bridge was opened, featuring a reinforced concrete structure and spanning 1,200 meters, with a main section of 185 meters. This modern bridge is a crucial link between the city and its southern suburbs (and the old bridge is still in use).

The bridges that cross the Riachuelo have always been more than just infrastructure. They have been vital economic, political, and social connectors, shaping Buenos Aires and Argentina as a whole. Their importance, both in the past and today, reflects deeper themes of Argentina’s history – a cycle of expansion and modernisation followed by crisis, and then persistence to enter a new cycle.

Historical importance of the Riachuelo bridges

Early Economic Gateway – The Riachuelo was historically a natural boundary separating Buenos Aires from its southern suburbs, particularly Avellaneda. In the colonial era, bridges like Puente Gálvez (1791) and later the Pueyrredón bridges were essential for transporting goods and people between the city and productive agricultural and industrial zones to the south.

Industrial and Immigration Boom (19th-20th Century) – As Buenos Aires expanded, the Riachuelo crossings became even more critical. By the late 19th century, Avellaneda had transformed into an industrial powerhouse, filled with factories, slaughterhouses, and workers. Many of those workers were European immigrants, and the bridges connected them to the city, fuelling economic growth but also highlighting social inequalities.

Political and Social Divide – The Riachuelo crossings have often symbolised the divide between Buenos Aires’ wealthier northern neighbourhoods and its working-class southern areas. Historically, the Pueyrredón bridges linked the country’s industrial workforce (and politically active unions) to the centre of power in the capital. Many labour strikes and political demonstrations have literally “crossed the bridge” over the years.

Modern-day importance

Massive Urban Congestion & Infrastructure Challenges – Today, bridges like the New Pueyrredón Bridge (1969) are among the busiest in Buenos Aires, handling thousands of vehicles hourly. However, they are also plagued by traffic congestion, pollution, and aging infrastructure.

Environmental Concerns – The Riachuelo remains one of the most polluted rivers in the world, and the bridges symbolize not just connection, but also Argentina’s ongoing struggle with urban environmental issues. Efforts to clean the river have been slow and “politically complicated” (which translated means “totally ineffective”).

A Social and Economic Fault Line – The Riachuelo bridges still reflect economic and social divisions in Argentina. Buenos Aires remains the country’s political and economic heart, but areas across the Riachuelo, such as Avellaneda and Lanús, have higher poverty rates and infrastructure deficits compared to the capital. This divide echoes broader national disparities between urban centers and neglected provinces.

Are the bridges a metaphor for Argentina’s history?

The Riachuelo bridges serve as a powerful metaphor for Argentina’s trajectory. It starts with promises and expansion (colonial trade routes, economic growth through industry). Then come the cycles of crisis and rebuilding (bridges collapsing, economic downturns, failed reforms). This inevitably fuels social divisions and political struggles (unions, protests, elite vs. working class). But a sense of national resilience emerges, and a cycle of modernisation re-starts (continued efforts to improve infrastructure, economic survival).

The fact that Buenos Aires has constantly had to rebuild and upgrade these bridges mirrors Argentina’s broader pattern of economic booms, collapses, and reinventions. They are a physical reminder of both Argentina’s potential and its persistent challenges. A potential never met, and challenges never beaten. Still, who knows, maybe next time.

These bridges are an integral part of La Boca

The bridges over the Riachuelo are deeply tied to the identity and history of La Boca. While La Boca is often associated with colourful houses, tango, and Boca Juniors, the bridges played a crucial role in shaping the neighbourhood’s economy, demographics, and culture.

La Boca as a Port and Industrial Hub

- In the 19th and early 20th centuries, La Boca was Buenos Aires’ main port before Puerto Madero and Puerto Nuevo took over.

- The bridges over the Riachuelo connected La Boca to Avellaneda, which was a major industrial and working-class district.

- Goods, especially wool, hides, and meat, were transported across the bridges, fueling both La Boca’s economy and Argentina’s export boom.

Bridges and Immigration

- La Boca was heavily populated by Italian immigrants, particularly from Genoa, many of whom worked in shipyards, docks, and factories.

- The bridges were their lifelines, connecting them to work, markets, and the wider city.

- The Pueyrredón Bridge and the Nicolás Avellaneda Bridge (a famous transporter bridge built in 1914) were especially key to linking the neighbourhood to industrial centres.

Protests and Political Symbolism

- La Boca has a strong history of labour activism, and many strikes and marches started in the factories of Avellaneda, then crossed the bridges into Buenos Aires proper.

- The bridges have witnessed many moments of social unrest, from workers’ demonstrations in the early 20th century to protests against economic crises.

Decline and Cultural Symbolism

- When Buenos Aires’ port activities shifted away from La Boca and industries in Avellaneda declined, the bridges became symbols of economic decay.

- The Nicolás Avellaneda transporter bridge was abandoned in 1960 and left inoperative for decades, serving as a metaphor for La Boca’s struggles with poverty, neglect, and marginalisation.

- However, in 2017, the transporter bridge was restored, signaling efforts to preserve the area’s heritage.

While modern bridges like the New Pueyrredón Bridge are crucial for daily transport, the old iron transporter bridge has become a historic landmark. The bridges still physically and symbolically link La Boca to Avellaneda, showing both the neighbourhood’s past dependence on industry and its modern role as a cultural and tourist hub.

Argentina's "Crisol de Razas" (melting pot)

So far I’ve mentioned the passion surrounding La Bombonera, the importance of the bridges that cross the Riachuelo, and the fact that La Boca is more than just a few painted houses in Calle Caminito.

But La Boca was created by immigration (from Latin: migrare, ‘wanderer’), which could be defined, at least in the Argentinian context, as “the engine of necessity — driven by survival”.

Between 1870 and 1930, Argentina experienced a massive wave of immigration, with approximately 2 million Italians settling in the country, making it one of the largest Italian diasporas in the world. Many of these immigrants came from regions like Liguria, Campania, and Sicily. They primarily settled in urban areas, with Buenos Aires and its neighborhoods, such as La Boca, becoming prominent Italian enclaves. This influx played a pivotal role in shaping Argentina’s cultural, social, and economic landscape.

Alongside Italians, Argentina welcomed a diverse array of European immigrants:-

Spanish: Spaniards were among the earliest and most numerous immigrants, significantly influencing Argentina’s language, culture, and traditions.

Germans: German immigrants established communities in various provinces, contributing to agriculture, brewing, and education.

Poles: Polish immigration began in 1897, with significant numbers arriving between the two World Wars, settling in areas like Llavallol, San Justo, and Quilmes.

Welsh: Starting in 1865, Welsh settlers established colonies in Patagonia, notably in Chubut province.

Argentina also became home to immigrants from other regions:-

Arabs and Levantines: Between 1891 and 1920, nearly 400,000 people came from the Levant, primarily from present-day Lebanon and Syria.

Jewish: Argentina hosts the largest Jewish population in Latin America, with communities established primarily by Ashkenazi Jews from Europe.

East Asians: The late 20th century saw an increase in immigrants from China, Korea, and Japan.

Argentina is often referred to as a “crisol de razas” (melting pot) due to its rich history of immigration. Genetic studies indicate that the average Argentine has approximately 79% European ancestry, primarily from Italian and Spanish immigrants, 18% indigenous ancestry, and 4.3% African ancestry. Furthermore, about 63.6% of Argentines have at least one ancestor of indigenous origin.

Between 2004 and 2023, Argentina processed nearly 4 million residency applications from foreign nationals, mostly from Paraguay (about 500,000 individuals), Bolivia (more than 330,000), Venezuela (160,000), Peru (150,000), and Uruguay (nearly 100,000). That’s more than 7% of the Paraguay population that emigrated to Argentina, and nearly 3% for Bolivia and Uruguay.

Argentina and Colonial Capitalism

Modern Argentina in the second half of the 19th century Argentina turned to a form of colonial capitalism targeted to entering the European market. It was driven by landowners and commercial oligarchies that held economic, social, and political power. Resident in the city of Buenos Aires, they owned large tracts of land in the Pampas plains. They saw the British Empire demanding sheep, cattle, grain and oilseed. Their territorial dominance next to the city’s port allowed them to acquire extraordinary geopolitical power, as compared to other producers in the country’s interior. The natural fertility of the Pampas plains meant they could raise and fatten cattle in conditions competitive with other regions around the world. With the introduction of wire fencing, breed improvements, and the railroad, this dominance was consolidated, positioning Buenos Aires as a major commercial metropolis.

At the same time, a powerful wave of migration from Mediterranean Europe (the weakest area in industrial Europe) entered through the port, settling densely in the city centre. This area covered several dozen blocks around the port (La Boca) and Plaza de la Victoria, today Plaza de Mayo. In just a few decades from its colonial urban structure, the “Great Village” (Gran Aldea) evolved into a large city with strong contrasts between immigrants and a rich and powerful land-owning elite.

The “migrant world” was one of discrimination, overcrowding, poverty, and exploitation, which fed, and to some degree still feeds, today’s social conflicts and class struggles.

La Boca and Barracas were two flood-prone districts, filled with warehouses and leather industries, breweries, distilleries, and wool washeries, with low, precarious houses made of sheet metal and wood, without drinking water or sewage systems, and with dirt streets, presenting an unpleasant view of life in Buenos Aires. Here were located the slaughterhouse, garbage dumps, and also the lowest-priced lots.

The city centre probably encompassed around 250 blocks around the Plaza de Mayo, where the public administration, finance, commerce, performance halls, and important schools were located. It was the wealthiest part of the city, where the elite resided, traditionally building their large mansions of up to three stories facing the plazas. However, around 1870, and continuing into the first decade of the new century, wealthy families began to move to the northern part of the Plaza and later to the Barrio Norte, where they had their summer homes. The yellow fever plagues of 1852, 1858, 1870 and 1871, were certainly one reason for moving out of the city centre.

This shift, combined with the arrival of immigrants, meant that the oldest and most dilapidated residences of the elite were converted into tenements. Rental housing, and multi-room apartments could accommodate more than 50 people. The first ones date back to 1850, and generated high rents. This spurred both building remodelling for tenements, and the specific construction of this type of multi-family structure by local entrepreneurs and a few wealthy immigrants. By 1880, 300 of the city’s 2,000 tenements were new.

With narrow courtyards, two or three stories high, and windowless rooms measuring 4 by 4 meters, a latrine at the back and only one door at the front, each could housed nearly 350 people. They had no shared kitchen, and each room cooked with a brazier at its door. Originally the same house would have been inhabited by at most 25 family members with their domestic staff.

Another characteristic was that families of the same origin and from the same village generally lived together in one building. After the yellow fever outbreak of 1871, which left these homes in jeopardy, the state once again ignored sanitation and building conditions, while the persistent arrival of foreigners and the growing demand for housing increased rents and overcrowding.

For workers, the tenement was a precarious solution, and for owners, a huge source of profit. At the beginning of the 20th century, running water reached the city center and some improvements began to appear, although in 1904 municipal reports indicated that every 60 people had one shower and one bathroom. These improvements did not immediately reach the suburbs, so rents remained high in the city centre, which led to the first major conflict in 1907, the Tenants’ Strike.

Downtown overcrowding became even more of a problem with the arrival of the tram and rail network. The high price of tram tickets made it impossible to travel far from work, except for state workers and those who were better off. They had already abandoned the city centre and had moved to middle-class barrios such as Flores or Palermo. But with the ‘federalisation’ of the city in 1880, which allowed the annexation of the San José de Flores, La Boca, and Barracas neighbourhoods, around 1900 there was a trend toward moving out of the downtown area, forcing the state to extend the railways. Between 1905 and 1912, the electrification of the tramway led to a drop in fares, and new immigrants and second-generation foreigners pushed an urban expansion, mainly towards the west and southwest.