During my visit to Buenos Aires in November-December 2024, I visited the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.

As I usually do, I tried to find a theme or topic that would help me focus, and at the same time define my pathway through the different rooms, etc.

Quite rapidly I decided to focus on the “gaze from the canvas”, and in particular what I could read into a few of the women’s faces depicted in the paintings on show. Even if my first example is actually not a canvas, but a wooden statuette of the Virgin Mary.

Today I zoom-in and focus on the face alone, the soul’s frontispiece.

Virgen con el Niño

A serene embodiment of medieval devotion

This is a detail of a polychromed sculpture depicting the Virgin Mary seated in a frontal, hieratic pose, holding the Christ Child on her lap.

The artist is unknown, but experts have attributed the sculpture to a workshop based in the province of Álava (Basque Country), probably in the capital, Vitoria. There are obvious marking on the Virgin’s waist which places the work in the first third of the 14th-century. It is common for medieval artworks, especially religious sculptures, to be unattributed. Many artists of that era worked collectively in workshops or under monastic orders, focusing on spiritual devotion rather than personal recognition. The emphasis in the full statue is on the theological concept of the Sedes Sapientiae (Throne of Wisdom), where Mary is seen as the throne upon which Christ, embodying divine wisdom, is seated.

A ‘hieratic pose’ refers to a formal, rigid, and often frontal posture used in art, especially designed to convey power, divinity, or authority. The term hieratic comes from the Greek hieratikos, meaning “priestly”, and is associated with sacred or ceremonial contexts.

This composition is characteristic of the transition between Gothic art and Romanesque art. What attracted me was firstly the delicate symmetry of the face, the almond-shaped eyes, the arched brows, the relaxed, gentle smile. And then the overall impression of calm and serene dignity. It’s not natural, not ordinary, it has something that goes beyond everyday life.

If you met someone in real life who looked like that, would you consider her beautiful? I’m not sure.

I think much would depend upon her voice. Which I imagine would be low, warm, and whisper-soft, perhaps with a maternal gravity, a quiet strength, like a flame that does not flicker, only glows.

In Spanish, she might say:

“Ven. No temas. Ya he visto muchas penas, y aún así, sostengo esperanza.”

(Come. Do not fear. I have seen much sorrow, and still, I carry hope.)

I can understand how many might take strength from praying to her.

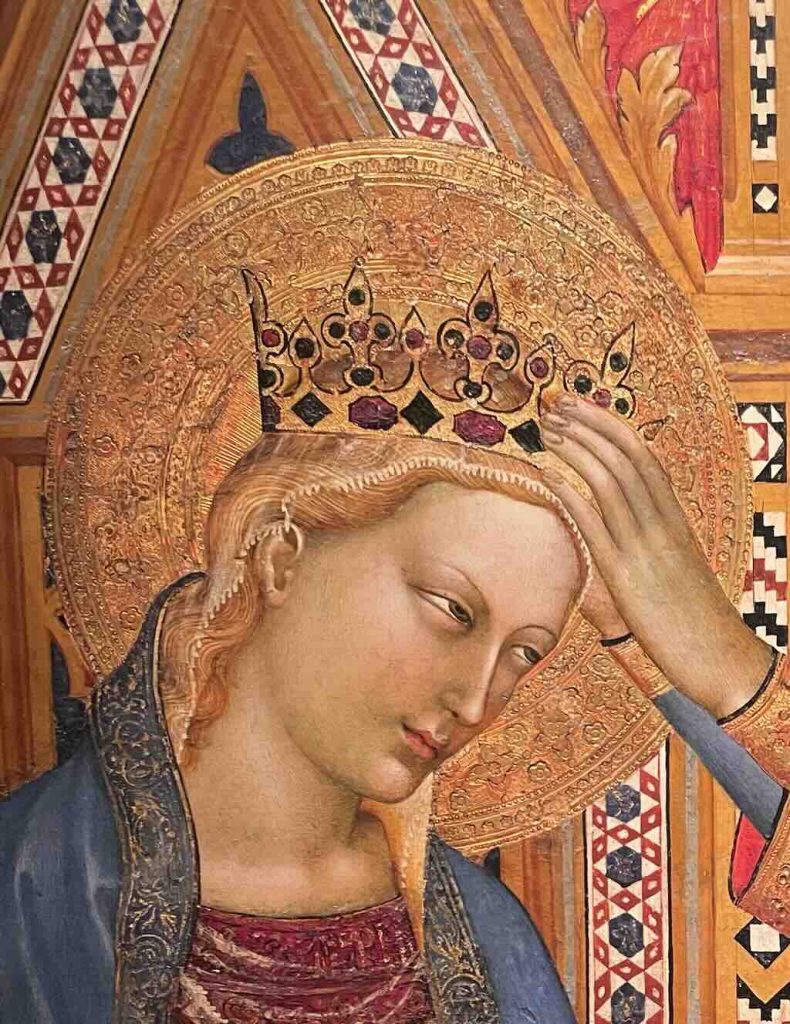

Coronación de la Virgen

The gilded splendour of the Virgin Mary’s celestial coronation

Art historians attribute this work to Giovanni da Milano (active between 1346 and 1369) based on stylistic analysis. Characteristics such as the use of tempera and gold on the panel, the depiction of delicate facial features, and the expressive gestures align with Giovanni’s known works, like the Polyptych of Ognissanti. Additionally, the painting’s dimensions and technique are consistent with his oeuvre.

The full painting portrays the Virgin Mary being crowned by Christ, a common theme in Gothic art and symbolising her exaltation (as Queen of Heaven). The composition is characterised by its use of gold leaf, which adds a radiant quality, and the figures are depicted with elongated forms and delicate features typical of the Gothic style. The background is richly gilded, emphasizing the heavenly setting of the scene.

During the 14th century, this type of artwork served both a devotional and didactic purpose. The Virgin’s coronation as Queen of Heaven, reinforcing the idea that she would pray for the salvation of Man’s soul from sin. The trend was towards a more accessible portrayal of Mary with tender more natural human-like facial features.

I looked at this painting several times, trying to decide if the smile was one of quiet self-satisfied at being crowned Queen of Heaven, or if is was one of resignation at having to accept a heavy burden. Which do you see?

How does this Virgin Mary compare to the previous wooden statuette of “Virgen María con Niño“?

Looking at the faces side-by-side, what is each trying to say?

With our wooden statuette, the Virgin Mary looks directly outward, not at the child on her knee. Her gaze is calm, reserved, maybe a little detached. It might even be something that would have been approached, even touched (probably only by the clergy and the elite). Was it meant to inspire a certain otherworld awe. Probably.

In the painting the features are a bit softer, slightly more natural, designed to connect more at a human level. Does it do that?

Both faces of Mary are doorways to a religious moment. For different people, in a different moment in time.

“What one Mary sees in the other”

Here is a little experiment…

The Wooden Virgin speaks about our gilded Mary:

I see you, Sister, bathed in tender gold.

Your head bends down, not in shame, but in grace.

There is softness in your brow, a quiet that calms.Yet you carry sadness. Like silk, weightless but deep.

You do not wear time, you wear feeling.

I see that your face was made to inspire faith, not fear.I wonder…

Is your warmth a kind of courage I never knew?

The Gilded Virgin replies:

You, hewn from pure nature and silence.

Your face does not move, yet it commands.

Your eyes hold strong, echoing what will not be said.I see no yielding in you, only resolve.

No smile, but no absence either.

You are the mountain of faith, not the garden.I wonder…

Is your stillness a form of love I never learned?

Princesa Margarita Gonzaga

A vision of austere, jewel-encrusted stillness

Frans Pourbus the Younger (1569-1622), sometimes presented as Frans Pourbus II, (El Joven), was a prominent portraitist during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, known for his detailed and realistic depictions of European nobility. In particular he was official court painter to Marie de Medici (1575-1642), Queen of France and Navarre, and the second wife of King Henry IV. We can see in this portrait that his work is characterised by meticulous attention to the textures of fabrics and the intricate detailing of jewellery.

This portrait depicts Margarita Gonzaga (1591-1632), daughter of Vincenzo I, Duke of Mantua (1562-1612), and Eleonora de Medici (1567-1611). She is portrayed in a richly embroidered brocade gown with an intricately adorned corset, complemented by shoulder pieces and half-sleeves. A lace-trimmed open neckline frames her face, which is topped with a pearl and gemstone diadem accompanied by an aigrette.

Margarita Gonzaga’s composed demeanour and direct gaze convey a sense of confidence and nobility. The elaborate attire and sumptuous accessories not only highlight her high social standing but also reflect the fashion and cultural values of the European courts during the early 17th century. The inclusion of luxurious textiles and intricate jewellery serves to emphasise her wealth and status, while the serene expression suggests poise and dignity.

If you are reading this, then stop, and take a long hard look at our Margarita. What do you see?

I see power dressing pushed to its highest, most ceremonial extreme. Forget the 1970s and 1980s, this is where fabric and jewellery don’t just ornament the body, they replace it. Her dress doesn’t merely signify wealth, it is a fortress, a manifesto. It casts a spell of sovereign stillness.

And it’s not just power dressing, it’s power looking. Her expression is composed, nearly severe, betraying neither warmth nor vulnerability. The expression “frozen dignity” comes to mind. There’s a controlled vigilance in her eyes, she knows she is being watched by us, but more important she knows she is being watched by history itself. Everything about her tells us we are looking at dynastic power, and a fortress of courtly discipline.

Remember, this portrait was probably painted when she was 16, possibly just after her marriage. She married Henry II, Duke of Lorraine 1606, at the age of 15 (he was 43). This was his second marriage, and it was clearly a political marriage meant to cement alliances between Mantua and Lorraine. He had previously been married to Catherine of Navarre, sister of King Henry IV of France, but the marriage was childless. This time his plans were different, even if finally they only had two daughters.

It’s interesting that the Metropolitan Museum of Art has a painting of the same person by the same artist, but dating to around 1605. So at the age of 14, and before her marriage. In this earlier portrait, Margherita is presented with youthful features, including flushed cheeks, but still with the elaborate attire characteristic of the period.

The portrait we have here is not Margarita the young woman, this is a person shaped by duty and ceremonial rituals, it is Margarita the symbol.

I can imagine myself walking at her side, equal to equal. She tilts just slightly her head in my direction. I sense the importance of the moment. She has been painted to embody dynastic duty, elegance, and wealth. A pearl among royal alliances. The tilt of the head has meaning. This moment is not mere ceremony. She wants to tell me something.

She does not do whispers, she speaks clearly and with poise, every syllable measured like a step on the polished marble floor. Her voice is bright but firm, trained in etiquette, and yet… it contains something that goes beyond mere pageantry.

She wouldn’t lower her voice, nor would she raise it, neither would it be soft. That would be for other moments. Now her voice would carry. It is a palace voice, trained to be heard, but not questioned. What she says is not a confession. It is a controlled revelation, one that she knows will be heard by those who are always watching.

“Creen que estoy vestida para complacer. No. Estoy vestida para esconder la espada que afilo en el alma.”

(They think I am dressed to please. No. I am dressed to conceal the sword I sharpen in my soul.)

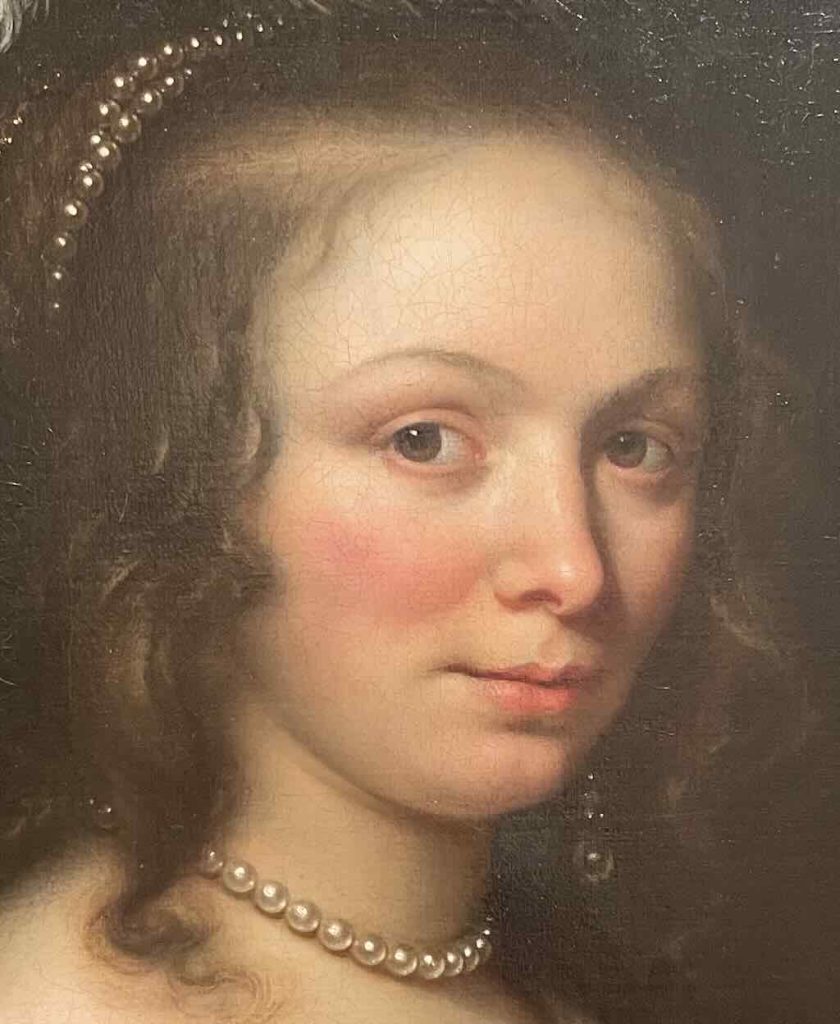

Retrato de joven con sombrero con plumas

Not a name, but a unforgettable presence

Govaert Flinck (1615-1660) was a prominent Dutch painter who initially trained under Lambert Jacobsz in Leeuwarden. He later became a pupil of Rembrandt van Rijn in Amsterdam, absorbing much of his master’s style. Over time, Flinck developed his own artistic voice, becoming a sought-after painter of portraits and historical scenes.

In this portrait, a young woman is depicted from the waist up, adorned in luxurious attire. She wears a richly coloured gown with intricate detailing, complemented by a velvet cloak draped over her shoulders. Her elaborate hat, decorated with red and white ostrich feathers, adds a sense of elegance and sophistication. The inclusion of pearl jewellery, both in her necklace and hair, further emphasises her high social standing.

The identity of the young woman remains unknown, leading to various interpretations of the painting’s purpose. Some art historians suggest that it might be a “tronie“, a study of a character or type rather than a specific individual. The luxurious attire and accessories could symbolise virtues such as beauty and wealth, aligning with contemporary ideals of femininity.

Flinck’s technique in this work shows a departure from the heavy brushstrokes characteristic of Rembrandt’s influence. Instead, he employs a smoother, more refined application of paint, resulting in a polished surface that highlights the softness of the subject’s complexion. The lighting is carefully controlled, with illumination coming from the left, casting delicate shadows that enhance the three-dimensionality of the figure. This approach reflects the influence of Anthony van Dyck, whose elegant portrait style became fashionable in Amsterdam during the 1640s.

However, Flinck used the same female figure in another painting, where she is portrayed as Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, complete with helmet and spear. This repetition indicates that the artist may have been exploring different thematic representations using the same model, a practice not uncommon in the 17th century.

Let’s assume it is a tronie, and that Flinck is wondering to himself, just how effective is his effort to capture the “Van Dyck effect”.

“Yes, I saw it. Just before she settled into pose. That flash. Not mischief, exactly. Something subtler, a delight in being seen. I tried to catch it, not too much. Just enough that if I watch her long enough, I begin to feel she is watching me back, amused.”

And if she could speak for herself, maybe, just maybe, she’d break character for a beat:

“You think I’m being serious. But I’m only holding still so you’ll wonder why.”

What attracted me in this face, was just that sense of fun, hidden, but …

I sometimes think that if I had lived in Amsterdam, circa 1645, I might have met her. Not as a portrait, not in a salon, but quietly, by chance, in a dim alcove of a tavern where the fire crackled and with the noise of the city dulled behind heavy shutters.

She’d be in her wide-brimmed hat, the plumes slightly softened by the heat, her face looking a little tired.

We might have shared some food. Cheese, dark bread, slices of pear, something pickled neither of us quite committed to. It wouldn’t have been a love story. Just a brief, comfortable moment with someone interesting, someone alert. She’d tear a piece of bread and hand it over without ceremony, eyes sharp, mouth composed, never quite smiling but never cold.

There would be a sense that she saw through things but didn’t feel the need to say so. The kind of woman who understands performance and doesn’t need to abandon it to be genuine. I’d be glad to have met her. Not to understand her, but simply to sit across from her while the firelight caught in her eyes, and to know that for a little while, the painting had let her step down from the wall.

Retrato de Mademoiselle Henault (Comtesse d' Aubeterre)

A poised noblewoman embodying 18th-century grace and refinement

Jean-Marc Nattier (1685-1786) was a French painter renowned for his portraits of the French nobility during the Rococo period, an aesthetic movement that flourished in Europe between the early and late 18th century. It was characterised by a certain lightness, elegance, and an exuberant use of curving natural forms in ornamentation. Nattier’s portraits often portrayed his sitters in an idealised manner, emphasising grace and sophistication. He was particularly skilled in showcasing the opulence and refinement of his patrons.

Portraits were vital in 18th-century France because they were visual expressions of power, identity, and refinement in a world where appearance was everything. In a society ruled by aristocratic privilege and courtly etiquette, especially under Louis XV (1710-1774), status wasn’t just assumed as a privilege of birth, it had to be constantly seen and performed.

Rococo portraits weren’t just likenesses as seen in a mirror, they were carefully staged social performances. This was a self-presentation, part reality, part fantasy. Through this painting, she becomes a kind of icon of noble femininity, poised, virtuous, and tastefully seductive. In a culture obsessed with elegance, wit, and lineage, a portrait by a fashionable a royal court painter like Nattier was both a personal brand and a public statement. It was a declaration of who you were, who you knew, and your ‘rank’ in society.

This is portrait of a woman telling her world, “This is how I wish to be seen. This is who I am. This is the role I command”. It was like a passport announcing “I am an aristocrat, I belong here“.

Above we see only the face of “Mademoiselle Henault”, but the full painting sees her seated, her body angled slightly, in a luxurious gown with intricate lace and satin details, and a subtle, pale background, ensuring the focus remains on the subject.

So who was Mademoiselle Henault?

The first thing to note is that portraits were often exchanged or displayed to reinforce family alliances, commemorate marriages, or attract advantageous matches. If she was recently married, this could be a portrait commemorating that shift in status. If unmarried (or betrothed), it might have played a role in signalling her desirability, and not just her physical beauty, but also her virtue, grace, and wealth.

The title “Mademoiselle Henault, Comtesse d’Aubeterre” is a challenge. “Mademoiselle” usually suggests an unmarried woman, but the title “Comtesse d’Aubeterre” is a noble title typically acquired through marriage. In some cases, French custom allowed for noblewomen to retain the “Mlle” honorific while being addressed by their family or inherited titles, especially in formal portrait captions that tried to balance status with lineage.

She is believed to be Catherine Le Bas de Montargis (1695–1728). She married Charles-Jean-François Hénault (1685-1770), a notable French historian, member of the Academy, and President of the First Chamber of Inquiries (Chambre des Enquêtes). I think they married in 1714, so this portrait dating from 1727, clearly was designed to express the poise, intelligence, and confidence of a woman deeply aware of her social role, but perhaps also enjoying its theatricality. In the 18th-century French aristocratic context, this expression of serene poise was part of the visual language of virtue and nobility. She knows her worth and expects it to be recognised, but she does not seem to flaunt it.

I have now moved from a tavern in Amsterdam in the year 1645, to a private salon in a hôtel particulier just off the Faubourg Saint-Germain. It is the year of our lord 1743.

Mademoiselle Henault is seated at a small round table sipping Champagne. She lifts her glass with a studied delicacy. Not to drink, but to be seen drinking. I’ve been placed near her because someone assumed conversation might be pleasant. But it isn’t.

There’s nothing in her I’d want to sit across from. Everything about her presence, her polished posture, her practiced half-smile, the smooth porcelain of her expression, signals someone absorbed entirely in her own importance. Not cruel, just incurious. The kind of person who’s been admired so long she no longer feels the need to offer anything back.

She doesn’t meet me in conversation, only tolerates me, if that. I don’t interest her, and she doesn’t pretend otherwise. She’d want someone of her own class, someone to mirror back the assurance that she belongs precisely where she is. Above everyone else.

It’s not just that she’s boring. It’s that she’s probably bored too. Bored with everything that doesn’t flatter or elevate her. A portrait of elegance, yes, but also of elegance without meaning. Her painting holds no secret. There’s nothing beneath the surface, because the surface is the only reason it exists.

Retrato de Manuelita Rosas

The dress projects power, and paints her into history

- The painting depicts Manuela “Manuelita” Rosas, daughter of Juan Manuel de Rosas, a dominant and polarising political figure in 19th-century Argentina. She is painted as a young woman of influence, poised, composed, and yet carefully managed in her visual narrative. Manuelita is shown in a frontal three-quarter pose, her upper body turned slightly while her gaze meets the viewer directly. The posture is elegant suggesting command without aggression, and presence without ostentation. This is a delicate balance likely shaped by her role as la Primera Dama no oficial, the unofficial First Lady during her father’s rule. Her head is elevated, suggesting her moral or political stature. Her right arm rests on a table, grounding her in a tangible world. This is a compositional anchor common in official portraiture, subtly denoting stability and control.

- In fact the commission defined the colour of the dress and the position “most analogous to morality and rank”. The dress, then, should be the “red of the federal homeland” and the sitter “with a smiling expression” in the “act of placing a request addressed to her grandmother on her desk. In this way, the young woman’s kindness was represented in her smile, and her role as intermediary between the people and the Supreme Leader, in the request she placed on the table”.

- Before looking at this portrait, we need to understand the woman it was intended to hide.

Manuela “Manuelita” Rosas was not merely the daughter of a dictator. She was the regime’s most refined weapon in the violent, absolutist order forged by Juan Manuel de Rosas, the Restaurador de las Leyes (see Pedro de Ángelis). When he crushed dissent in the name of Federalism, she was the regime’s soft edge, the red-velvet façade of a government built on fear. Her charm was not innocent. It was political currency. Her presence was not incidental. It was strategic. She was not on the margins of power. She was one of its enforcers.

In an era when opposition meant prison, exile, or death, Manuelita served as the image that softened the brutality. While men were shot in the back for uttering Unitario sympathies, she smiled at foreign emissaries, wrote graceful letters to the families of the fallen, and attended state receptions in Rosas-red dresses. She hosted diplomatic salons where she charmed European powers and painted the regime in colours they could stomach. All while her father’s Mazorca (secret police) soaked the streets in blood.

This was not a contradiction. It was a division of labour.

She was the embodiment of the Federalist state in its most seductive form. With a soft voice, and an unbreakable message. Her femininity was political theatre.

Federalism didn’t just need soldiers. It needed symbols. Manuelita became one. The propaganda apparatus cast her as the “Mother of the People,” a Madonna in red, the emotional conscience of a ruthless state. Her every appearance at hospitals, schools, funerals, …, was choreographed to reinforce the Rosas cult. She was an active agent in shaping a new national identity, not based on dialogue or pluralism, but on loyalty, ritual, and submission to the Father-State.

In that Argentina, to be a good citizen was to wear red, speak carefully, and revere the Restorer. Manuelita didn’t just embody that order, she helped write its script.

Historians who paint her as a proto-feminist miss the point. She did not seize power in defiance of men. She was given power to help them maintain their rule. Her diplomacy served the sword. Her letters covered the screams. She was the mirror in which Federalism admired itself, an impenetrable image of serenity and civility.

Even in exile, she did not break. When Rosas was deposed in 1852, she followed him into darkness without protest, cared for him in England, and protected his image until his death. She died in 1898, long after his downfall, but never once betrayed the red creed.

We are going to need the full portrait to understand what that face is telling us.

What remains of Manuelita Rosas today is a portrait, literally and metaphorically. In Prilidiano Pueyrredón’s famous canvas, she stands, poised and composed, the embodiment of grace. But behind the silk and velvet lies steel. Behind the smile lies silence, the kind that knows where the bodies are buried.

She is not a tragic figure. She is a victorious one. Not in the name of freedom, but in the name of order. The regime fell. Its myths endured. And Manuelita Rosas remains one of the most effective political operatives in Argentine history. Not despite being a woman, but because she weaponised the role perfectly, in red on red.

In this large portrait, red is used in different variations to define most of the objects depicted, from the recently fashionable velvet dress, the carpet, the curtain, the armchair, even the bouquet in the vase. The sitter, then 34 years old, is slightly profiled to the right, contrasting little with the greenish background. The white lace of the skirt, discussed by the artist to enhance the visual effect, lends luminosity to the chromatic uniformity. She wears a striking array of diamond jewellery – a diadem over her bandeau hairstyle that complements the red chignon, a necklace highlighted by the open space of the “berthe” neckline, earrings and a brooch, as well as gold bracelets with precious stones and rings on both hands. The commission was intended for exhibition at the gala ball in her honour. Lithographs of the ball were also planned for distribution to attendees.

After the Pronunciamiento against Rosas in May 1851, the Buenos Aires federalists were obliged to strengthen their usual “federal expressions” in the functioning of the regime. The portrait of Manuelita, although belonging to the universe of these political practices, nevertheless expresses a change in the use of images, which until then had been dominated by the omnipresent effigy of Rosas. The image of Manuelita, a person esteemed even by the Unitarians themselves, was presented as the intermediary between the people and the government. Pueyrredón’s portrait affirmed Manuelita as a federal example of filial love and piety, private virtues that were never more necessary than in the face of the imminent end of the regime.

Manuelita wears an off-the-shoulder dress designed to reinforce the sense of restrained refinement, femininity, and wealth, contrasting with the more formal or matronly high-necked fashions of the time. The aim may have been to emphasise her youth and perhaps her political role as a more accessible, modern figure.

The face is evenly lit, highlighting a rational presence, a key Enlightenment virtue for a politically engaged woman in the public eye. Her face is calm, closed-lipped, and self-possessed. There’s no overt smile, but neither is it cold. This is the carefully curated expression of a woman aware of her public function.

For me, her face is one of tight-lipped control, her eyes look straight past the viewer. This is not a portrait designed to charm, or offer intimacy, at best it’s a resigned performance. At worst, it’s more like a clinical documentary, promoting the colour red.

During my visit to the museum, I picked this face because I felt it was of someone I would want to avoid at all costs. And I was right.

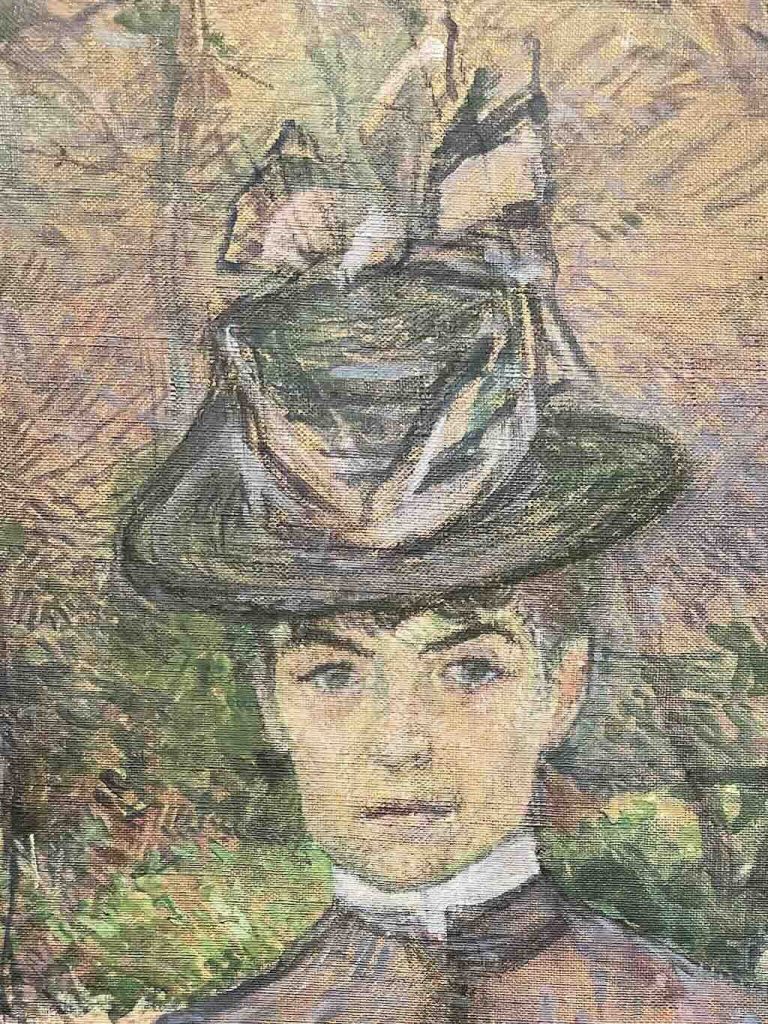

Retrato de Suzanne Valadon

Capturing the strength and complexity of a pioneering female artist

This is an oil-on-canvas by Comte Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (1864-1901), date to 1885. It is a portrait of Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938), an artist and model in her own right.

While Toulouse-Lautrec did use oil on canvas, he is far more famously associated with lithography, posters, and mixed-media works on cardboard or board, often using oils thinned with turpentine, or combining oil and gouache. These quicker, looser formats suited his fast, observational style and were also linked to his immersion in nightlife, cabaret culture, and ephemeral performance.

Oil on canvas demands more intention, more commitment. For Toulouse-Lautrec it was a more intimate, serious, or emotionally-investment. He wanted to respect the classical tradition of portraiture, and to give durability and weight to his subject. It might be considered a mark of deep personal respect.

So, who was Suzanne Valadon?

Born Marie-Clémentine Valade, she began her career as a circus acrobat before an injury led her to modelling for artists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec. Encouraged by Degas, she developed her own artistic career, becoming the first woman admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

The portrait of Valadon (above we only see her face) is depicted in a three-quarter view, standing against a backdrop of autumnal foliage. Her direct gaze and upright posture convey confidence, assertiveness and individuality, qualities that would define her later success as an artist.

Looking back at my visit, why did I take a photo of her? Firstly, I’ve always liked the way Toulouse-Lautrec appears to “catch the moment”. Secondly, I imagined taking some photos of her, just as I would take some of my wife. My wife would pull faces, then try to hold a pose for a moment, before laughing. I could imagine Valadon doing the same, and what we see here is the pose, before she burst out laughing.

Just as my wife trusted me, so Valadon trusts Toulouse-Lautrec to capture her truth. A frank, open gaze, no coyness, no evasion, no attempt at seduction, she’s present, alert, composed (for a second).

Let us just imaging for a moment. Toulouse-Lautrec pulls back, cleaning his brush with an old, stained cloth. He is still looking at the canvas, and suddenly Valadon is standing beside him.

The artist in her speaks…

Eh bien… me voilà.

(une pause)

T’as mis le doigt sur un truc… j’sais pas comment. Mais c’est là.

“So that’s me, is it?”

(pause)

“Not bad. You’ve caught something… I don’t know how.”

Then as a friend, with just a trace of suppressed mischief…

Tu m’as faite presque respectable.

Faudra pas que ça devienne une manie.

“You’ve made me look almost respectable.

Let’s not make a habit of it.”

Joven Oriental

She stares with sphinx-like calm

Juana Romani was born Carolina Giovanna Carlesimo (1867–1923) and after moving to Paris at the age of 10, later transitioned from modelling for renowned artists to establishing herself as a distinguished painter. As an Italian immigrant and working-class woman in Paris, she could easily have been marginalised, both socially and artistically. Working first as a model gave her access to the art world, but also risked her being trapped in a sexualised or subordinate role. She escaped that through sheer talent and stylistic force, but the tension always hovered in her work. She often featured enigmatic female figures, leading to speculation about their autobiographical nature.

Several portraits of Juana Romani exist, painted by contemporaries such as Ferdinand Roybet and Jean-Jacques Henner, showcasing her distinctive features and the artistic circles she frequented.

Romani’s frequent portrayal of solitary, introspective women has led art historians to consider these pieces as veiled self-portraits. Her ability to capture the nuanced expressions and moods of her subjects suggests a deep personal connection, possibly reflecting her own experiences and emotions. Remember this as you read on.

Joven oriental belongs to the late 19th-century European Orientalism, a movement marked by imagined, often exoticised depictions of Eastern subjects, styles, or attire. Here, Romani draws on that tradition but re-centres it around the female subject herself, not the context. She had an academic precision in using chiaroscuro, dramatic light-dark contrasts to create depth and emotion. But she then used a looser, almost impressionistic texture in areas like the hair and robe. The style blends an academic Realism with hints of Symbolism. For example, this portrait is some ways is less a real person, and more an embodiment of beauty and mystery.

It’s important to understand that in the 19th century, and especially in Parisian salons, female subjects were often objectified. Whether as odalisques, courtesans, allegories of “virtue” or “vice”, or simply idealised nudes, they were frequently presented “ready made” for the male gaze, i.e. beautiful, passive, consumable. Their bodies were on display, and their identities were often secondary, or even irrelevant. They were, in a way, metaphorically and sometimes quite literally for sale in the art world, echoing broader social roles assigned to women at the time.

Romani disrupted that. She painted women with psychological weight, interiority, presence. Her portraits often featured women who stared back, self-possessed, assertive, sometimes enigmatic, sometimes defiant. They weren’t anonymous muses or abstract ideals, they were real people. They weren’t there to seduce the viewer or to embody male fantasies.

Romani gave dignity and complexity to her subjects, which in itself was a radical act for a female painter in a patriarchal art world.

I took this photo because it’s a striking portrait, defiant, but somehow fragile.

If you have read this far, I would suggest you read again my text, let it sink in, before reading on…

Romani’s career ended tragically when she was institutionalised in 1904. The last two decades of her life were spent in silence. The societal context here is cruel and poignant. Women who did not conform, who were too eccentric, too independent, or too difficult, were often pathologised and removed from view.

Knowing this, her earlier portraits take on a prescient quality. Many show women alone, lost in thought, resisting easy interpretation. They are not just decorative.

Romani deserved a better fate.

Los ópalos

A jewelled procession of mystery and decadence

This is actually just one face taken from several in a larger painting called Los Ópalos meaning “The Opals”, the iridescent, semi-precious stones known for their shifting colours and ethereal, inner glow.

Los Ópalos is a work by Spanish painter Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa (1871–1959), created around 1904. He was a prominent Spanish painter associated with the Catalan Modernisme movement and Symbolism. He studied in Barcelona and later moved to Paris where he was influenced by the Nabis group, e.g. art as a synthesis of metaphors and symbols. His work is characterised by vibrant colours, decorative elements, and a focus on modern society’s decadent aspects.

In Los Ópalos Anglada Camarasa presents a frieze-like arrangement of sensual, elegant women standing closely together. The figures are depicted with undulating, sinuous lines, emphasising their graceful forms. I was attracted to just one of the faces, but I will admit it lost something in being removed from its context.

It’s interesting, because I liked the overall impression of this painting, but at the time I just focused on one face. Now I’m just as interested, perhaps even more interested, in why the artist created this unusual composition.

It’s also interesting in that historians and art experts always want to give everything a deep sense. Either it must be part of a past movement, or set in a present movement, or pointing to a future movement. Here the preferred view is fin-de-siècle (French for “end of the century”) referring to the cultural mood in Europe, especially in France and Spain, at the end of the 19th century. It was a time marked by a sense of decadence, and an excessive obsession with beauty, luxury, and artifice. The experts say they detected a certain spiritual fatigue, boredom, even cynicism with the concept of romantic idealism. And there was an emerging anxiety about the coming century that would be brutal, mechanised, and modern in a stark new way.

Remember, we are in 1904 and the Eiffel Tower had been lit with electricity since 1900. The Paris Métro had opened in 1900, fostering anxiety about speed, crowds, and anonymity. The automobile was no longer a toy of the rich. The wireless telegraph was connecting continents without wires. Still very few people understood how these things worked.

Also Sigmund Freud had published “The Interpretation of Dreams” in 1900, and by 1904, his ideas were spreading in salons and among intellectuals. Artists and writers began to depict figures in states of trance, reverie, or ambiguity, exactly the tone in Los Ópalos.

The dominant aesthetic trend in 1904 was still Art Nouveau, very ornamental, organic, and sensual. Symbolism, though waning, was still deeply influential as can be seen in copious surface decoration in Los Ópalos. But Fauvism was about to explode (Matisse would show his bold colour works in 1905).

And we should never forget that the Russo-Japanese War began in 1904, which was a major shock to European powers, especially when Japan would later win. France and Britain signed the Entente Cordiale in April 1904, formalising cooperation after centuries of rivalry.

Los Ópalos was on the way out, and the “New Woman” was emerging. Women who were educated, independent, artistic. This both thrilled and threatened male society. Female figures in art would become autonomous, even dangerous.

These figures and faces in Los Ópalos are more than women, they are symbols.

I’m going to challenge whoever is reading this post. Los Ópalos are a transition from the past to the future. I’ve described some images of women from the past, and I will now continue to describe some from the future (post 1904).

Will you recognise that the women of Los Ópalos stood on a threshold. They were gorgeous and ghostly, seductive and decadent, passive and remote.

By 1917, and beyond, all that will be forgotten, never to return.

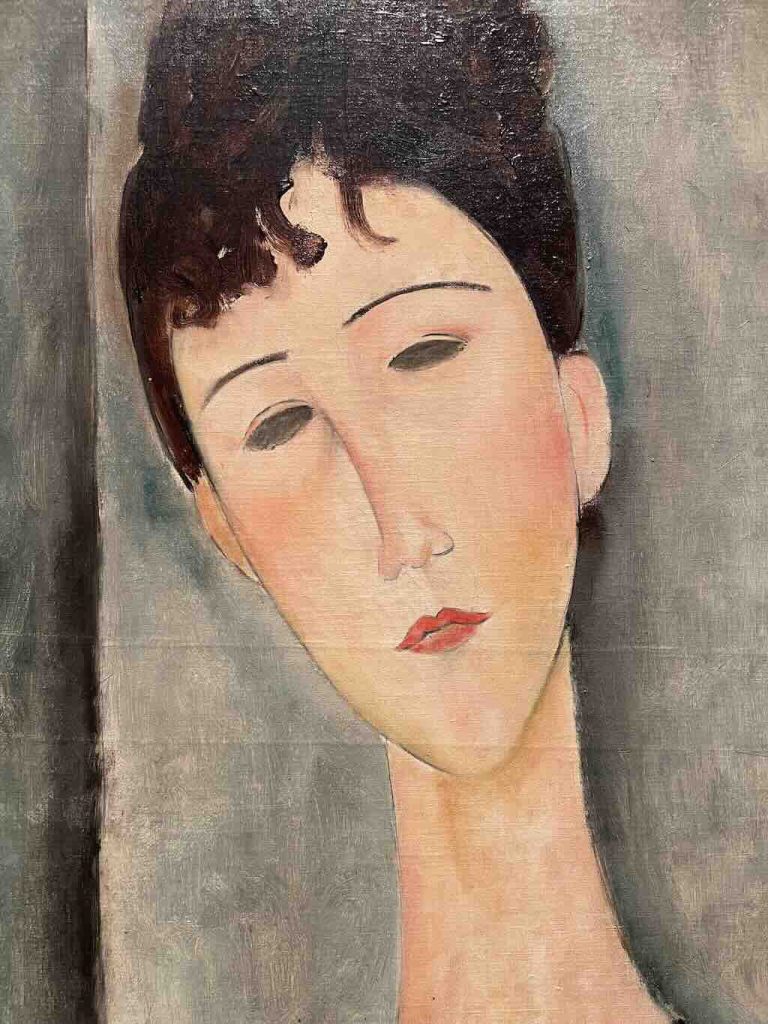

Figura de mujer

Her face reveals nothing, yet suggests everything

Amedeo Modigliani’s (1884-1920) portraits from this period (1917-20) often feature stylised elongation swan-like necks and oval faces, influenced by African masks and sculptures, reflecting his interest in non-Western art forms. The omission of pupils in the almond-shaped eyes directs focus to the form and composition rather than individual identity, inviting viewers to engage with the universal aspects of human expression. The simplified lines and harmonious curves contribute to a sense of elegance and timelessness, aligning with the aesthetics of the École de Paris (1900-1940), of which Modigliani was a part.

Modigliani’s brushwork here is smooth, almost sculptural in its restraint. The background is non-descriptive and flat, serving to isolate and elevate the subject. The lines are clean, soft, and almost calligraphic. There is little texture, so volume is suggested more by hue and shape than chiaroscuro.

Figura de mujer belongs to Modigliani’s mature portraiture phase, closely tied to the École de Paris movement, but he resisted complete abstraction. His work walks a tightrope between modern stylisation and classical poise.

I wonder why I took this photo. Did I see something interesting, or was it simply because of the artists name? Perhaps it was just the shocking difference with what I had seen so far in my walk through the museum.

I like the palette of soft, earthy tones and the colour balance. I like the sense of quiet serenity and elegance. Do I care that Modigliani was deeply influenced by African art, particularly masks? Not really. The large, almond-shaped eyes and simplified facial expressions reminds of the stylised features in Japanese mangas. But, so what.

Who was she? In many of Modigliani’s works, particularly his portraits of women, the identity of the subject can be a point of intrigue (not for me, I don’t care). For Figura de Mujer, though, there’s no definitive, widely known answer about who the woman was, as Modigliani often painted people from his circle. It could have be a friend, lover, or just a model.

If you are looking for an abstraction of a face, a woman’s face, then this maybe a good starting point. Perhaps the real purpose of this portrait is as a reminder that faces can be so different. How do we compare this portrait with that by Juana Romani, or with the face painted by Anglada Camarasa?

They do have one thing in common, they are portraits of no-one, and therefore of everyone.

A cynic might say “fame fades — mystery sells”, which is certainly not the case for Modigliani, who died of tubercular meningitis, destitute and largely unrecognised by the mainstream art world.

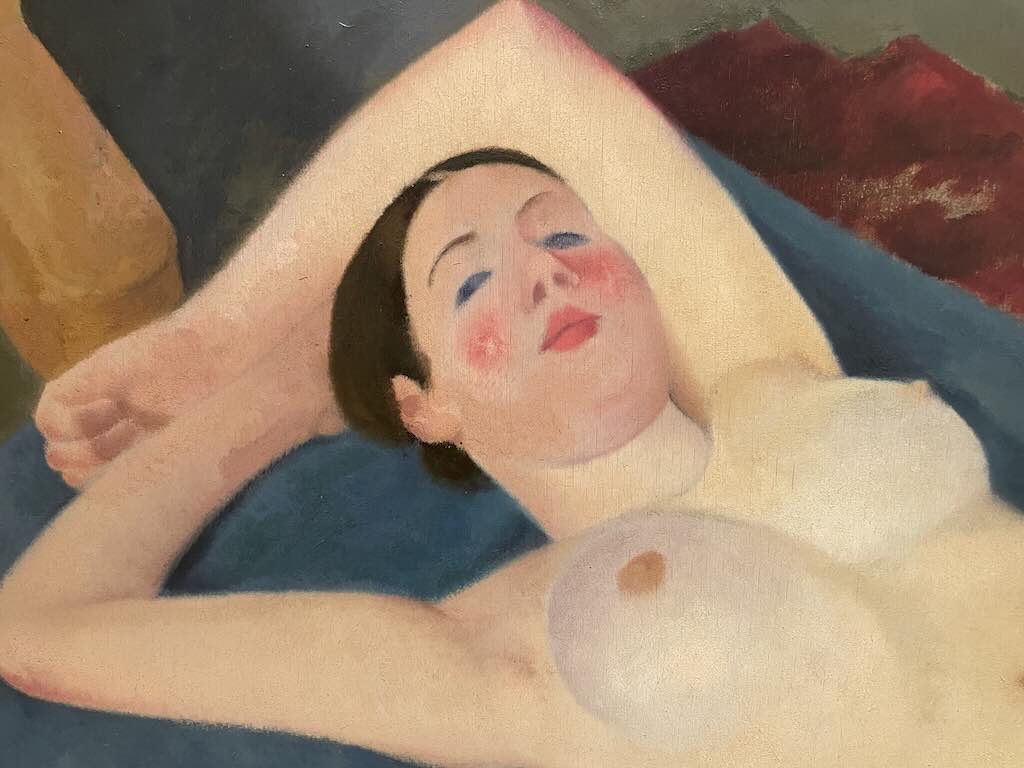

Rosanna

She lies as if sculpted from pure thought

There’s a sculptural stillness to the body. A sense of being rather than doing. Felice Casorati’s (1883-1963) application of paint is tight and measured, avoiding visible brushstrokes. The geometry of the composition is carefully calibrated. The figure doesn’t recline but floats in an abstracted realm of presence and form.

Rosanna was painted in 1929, during a period often called the “Return to Order” (retour à l’ordre), a European reaction in the 1920s to the chaos of World War I and the radical fragmentation of Cubism and Futurism. Artists, including Casorati, began looking back to classical symmetry, Renaissance poise, and metaphysical silence.

Casorati was associated with the Italian Novecento movement, which sought to reconnect modern Italian art with its Roman and Renaissance roots, filtered through a modernist clarity. In Rosanna, the influence of Piero della Francesca and Mantegna is seen in the volumetric clarity and “harmonic proportions”. Yet the metaphysical tone, where the real becomes surreal through stillness, connects him with contemporaries like de Chirico.

This painting lives in the borderland between Magic Realism and Neoclassical Modernism. The figure is entirely believable, but the context around her is not.

At least that’s what the experts write!

Rosanna herself may have been a specific model or simply a perfect example of metaphysical stillness. The idea is that there is no story, no past, no future, just being present. Maybe, that’s why I took the photo.

The still face doesn’t tell us what happened. It tells us that something is.

Cerril

She stands as the quiet axis of tradition, a vivid portrayal of rural Argentine life

Mario Nicolás Irineo Anganuzzi (1888–1975) was an Argentine painter born in Buenos Aires. A self-taught artist, he is known for his works depicting regional and traditional themes, often focusing on rural life and landscapes.

After the last few portraits, its nice to get back to someone who actually looks human!

Cerril dates from 1929 (the same year as Rosanna seen above) and the entire painting presents a scene of rural life, focusing on traditional Argentine customs.

I have zoomed-in on the face of a woman, making it a portrait, when it fact the painting is more like a landscape of Argentine country life.

Though the scene is populated by rural life, with gauchos and local villagers, the female figure commands particular attention. She is not placed at the periphery. She is central, both compositionally and emotionally. Her stance is upright, while others bend, toil, or move, she stands.

Anganuzzi does not highlight her with artificial glamour, she blends into the land. Her gaze is reserved, honest, a little fragile. You feel you could speak to her.

Among the often grand, mythic representations of women in European art, this Argentine woman is a portrait of the everyday. She has presence.

I remember spending sometime looking at her, and I somehow linked her with the next face. I couldn’t just move on and take my next photo of another painting, I needed something more solid.

Desesperación II

A silent cry capturing the profound depths of human despair

Luis Falcini (1889-1973) was a seminal Argentine sculptor known for bringing psychological depth to figural sculpture. A student of Lucio Correa Morales, Falcini absorbed classical technique but quickly veered toward expressive realism. He often focused on the inner life of his subjects, with themes exploring labour, struggle, motherhood, and existential suffering. His works reside in a specific form of Argentine social realism.

This bronze figure, dated 1961, manifests emotional agony, the silence after a piercing scream. We see that there is nothing romantic about despair. Falcini has retained the tactile marks of creation, lending immediacy to the emotion. If we look carefully he sculpts ‘absence’ to help evoke emotion. We can see that the absence of detail actually adds to the sense of total despair. As if true despair, removes unnecessary detail.

Desesperación II makes no concessions. There is dignity, but no beauty. I felt it aligned well with the last face of Anganuzzi. But in my mind, after such a cry of despair can only come death.

I couldn’t leave the museum with that thought, so I walked back to find this final example, of a nice friendly female face.

Looking back now, perhaps, “not unfriendly”, is a better definition.

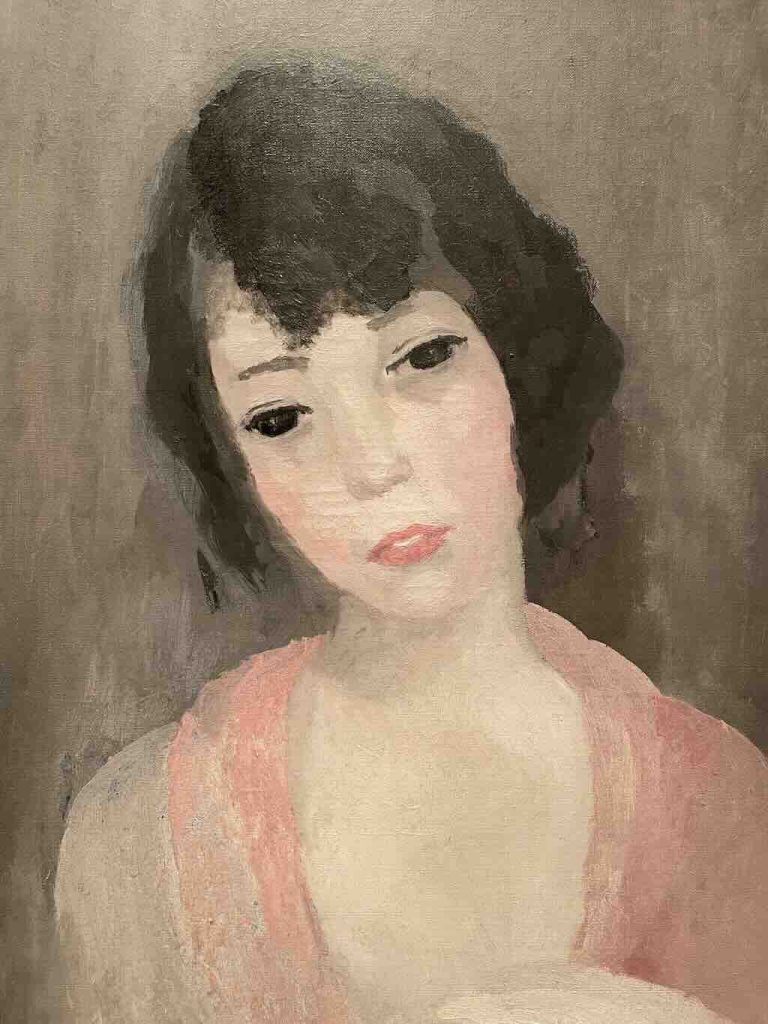

A self-portrait that floats rather than declares

In this self-portrait, Marie Laurencin (1883-1956) presents herself with elongated facial features and large, almond-shaped eyes. She was associated with the Cubist movement through her connections with artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, yet her work maintained a distinct softness and femininity. Her style is often described as lyrical, decorative, dreamlike and quite feminine.

It’s difficult not to see a touch, or perhaps a nod, to Modigliani. Both active in the early 20th-century Parisian art scene and they certainly shared mutual acquaintances.

Both appear to have adopted a certain degree of stylisation and abstraction, yet have arrived at different artistic destinations. Laurencin is certainly more dreamy, graceful, decorative, more feminine. Modigliani is more detached, abstract, withdrawn, more primitive. In a word, she is “warm”, he is “cold”.

Not Friends. Not Even Close.

Marie Laurencin and Amedeo Modigliani in Opposition

If Marie Laurencin’s self-portrait and a Modigliani woman ever found themselves sharing a gallery wall, it wouldn’t be a friendly reunion. It wouldn’t be a reunion at all.

Laurencin paints herself with care. She wants to be soft, poised, elusive, yet seductive. She constructs femininity as a stylised language of delicate reserve. This is a woman aware of how she is seen, and in full control of the image she offers.

Across the room, Modigliani’s woman doesn’t offer anything. She gives nothing away. Her expression unreadable, her gaze at times vacant, at times defiant. She isn’t performing. She’s enduring.

These two don’t speak the same artistic language, or even breathe the same air. You can almost taste the perfume in Laurencin’s world. Modigliani’s world is raw and unadorned, it doesn’t lack perfume, it refuses it.

One was a self-fashioning woman. The other, a figure fashioned by a man.

They don’t dislike each other. That would be too easy.

They simply belong to different planets, orbiting incompatible truths about what it means to be seen. No, what it means to exist.

I left the museum refreshed.