We all know what a match, matchstick and matchbox are, but what is a matchbook (or matchcover)?

Wikipedia tells us that the Chinese had little sticks of pinewood impregnating with sulphur and stored ready for use. The earliest American patent for the phosphorus friction match was granted in 1836, but the first improved safety match was not introduced until around 1850–55, and millions of matchboxes were sold.

In 1892 a lawyer and inventor Joshua Pusey submits a patent for a folded piece of cardboard, carrying matches and a striker inside. Fed up with carrying bulky boxes of wooden matches, he set to work to invent paper matches that would be lighter and smaller. He called his invention ‘flexibles’ due to the fact they could easily slide into a suit pocket with little evidence of their presence. By the late 1890’s, Pusey’s patent had been sold and matchbooks increasingly became a cost-effective advertising method.

Why do I have some old matchbooks?

Travelling around for work and pleasure I picked up a variety of matchbooks and brought them home. We used them to light the open fire in the living room, and we collected the matchbooks in a small bowl. I guess we gave up collecting them when the bowl was full. Very recently in the back of a cupboard I found that bowl, still full of old matchbooks (and a few mini-matchboxes).

Because they were collected in hotels and restaurants, each brought back a specific memory, and each related to a specific place and date.

I don’t consider them a collection, but I couldn’t just throw them away. So I decided to keep them, scan the matchcovers, and put a place and date on them.

What exactly is a match?

By the 1940s, over a million Americans had become collectors of matches, or ‘phillumenists‘. This is a word that uses a combination of the Greek ‘phil’ (loving) and Latin ‘lumen’ (light). Today matchcovers have almost disappeared as an advertising tool, but there are still collectors for them. In some ways, as the modern-day matchbook disappeared, they have become more collectable.

As one collector wrote “And that, my dear friends, is why matchbooks are my muse, the ultimate ode to memory, Alzheimer’s, and art”.

And as someone else wrote “the true beauty of the match collecting hobby lies not only with their practical use around the home but also in the way that they can act as a memento of unique experiences as well those personal stories surrounding those experiences“.

The first matches had heads composed of white phosphorus, potassium chlorate, and glue, but the presence of white phosphorus made them highly poisonous. The discovery ca. 1844 of the way to produce red or amorphous phosphorus, which is less poisonous than white phosphorus and does not give rise to harmful emissions, marked an important innovation in the methods of manufacturing matches. The practical application was called Swedish matches. The head of the match was made of potassium chlorate, glue, sulphide of antimony and oxygen-developing substances. The amorphous phosphorus was contained in a mixture that was spread on the sides of the box, and the matches worked only if rubbed on this mixture. These were the first safety matches, often called simply amorphous matches.

Numerous reports mention the importance of the ‘Congreves’ match, named in honour of William Congreve, inventor of rocket artillery. They were first manufactured and sold in England (1827) by John Walker, a grocer from Stockton-on-Tees. They were made of a stem impregnated with sulfur and provided with a head containing antimony sulphide, potassium chlorate and rubber, and were ignited by rubbing on a strip of sandpaper.

It would appear that in 1829 a young chemist named Samual Jones imitated the match originally developed by John Walker, and called them ‘Lucifers’. Jones was the first to sell matches in a small rectangular cardboard box. I remember in the 1960’s some people still calling matches ‘Lucifers’. Check out “Phosphorus and the history of the match“.

White phosphorus matches continued to be manufactured and used especially in southern Europe, but around 1900, several other compositions without white phosphorus were studied and patented, including industrially important compositions based on phosphorus-sesquisulphide, a non-poisonous product first adopted in France in 1897.

Since the use of similar compositions were struggling to become widespread, an international agreement was advocated to combat phosphorism and phosphorus necrosis. Two international conferences followed in Bern in 1905 and 1906, the result of which was the Bern Convention (26 September 1906). With it, France, Germany, Denmark, Holland, Switzerland and Luxembourg committed themselves to ban white phosphorus from 1 January 1912. Other nations then followed, i.e. England in 1908, Sweden in 1920, Czechoslovakia and Austria in 1921, Belgium in 1922. Italy joined the Berne Convention on 6 July 1910, but due to WW I the ban was only sanctioned on 31 December 1920, effective from 1 January 1921.

The United States of America did not immediately adopted laws prohibiting the use of white phosphorus for matches. However, in practice they achieved their aim by applying a very high tax on the type of matches (sulphurised) for which white phosphorus was mostly used, and by granting imports (always with a very high duty) only to safety matches.

The types of matches in use today can be classified, as far as the head is concerned, into matches with phosphoric heads, which light up by rubbing on any rough surface, and matches with phosphorus-free heads (amorphous) which light up only if rubbed on a surface smeared with a phosphoric mixture.

In terms of consumption, the most widespread in the world are safety or amorphous matches, small paraffined sticks without phosphorus. They are often contained in boxes, sometimes made of cardboard, but more commonly a very thin sheet of wood, covered with paper. They represent the most current genre in northern, central and eastern Europe (England, Scandinavia, Holland, the Baltic States, Russia, the Balkan Peninsula, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Switzerland) in North America, in Asia, in almost all of Africa.

The so-called paraffin matches are also still used. These are paraffined sticks with phosphoric heads and sold in boxes, generally made of wood, sometimes made of cardboard. Since they can be ignited by rubbing on any rough surface, they are sometimes referred to with greater precision as ‘anystrike’ matches.

Finally, in some countries, matches made of paraffined cardboard (“Minerva“) with heads without phosphorus. You find them in sachets made of a strip of thin cardboard, which, folded and sewn in the middle, holds the thick cardboard sheet, also folded in two, in which the matches are cut, without being completely separated. These are arranged in two rows, and carry the flammable head at the free end. These sachets, although representing a type of secondary consumption, are widely used, especially in Germany and North America, for advertising purposes.

Collecting matchbooks

There is a webpage on collecting basics, which noted that almost all collectors carefully strip the matches out and collect the covers (but never remove the strikers).

However I also found some advice about storing old matches in a aluminium container with a screw-on cap. This type of storage keeps out moisture which will otherwise ruin the matches.

I stripped out the matches, separating them from the covers, but what to do with the unused matches? The first thing is not to underestimate the danger of a collection of matches sitting in a corner or in the back of a cupboard (something I had not thought about in the past). There is a lot of advice about how to safely deal with both used and unused matches. Suffice to say that I soaked them in water for several hours, then placed them in a sealed plastic bag containing more water. Later I removed them from the bag and threw them soaking wet in the waste. As far I know matches are biodegradable, and perfectly safe after being soaked for several hours.

Normally, the only “full-books” (intact matchbooks) collected are those wherein the matches, themselves, have art work on them (called “features” if the matchsticks have detailed pictures on them, and “printed sticks” if the matchsticks just have text on them).

Otherwise the stripped covers are then pressed flat in a variety of ways in preparation for mounting in albums.

The main rules to keep in mind are not to damage or deface covers in any way. Never cut, glue, or staple covers. Never write on the outside of covers, and don’t wrap them tightly in rubber banded stacks. Don’t store them in damp areas or areas where they will be directly exposed to sunlight for extended periods.

Factors like condition, age, and rarity determine the value of a vintage matchbook.

For collectors, the value of a vintage matchbook depends largely on its condition. Unstruck covers, which have not been used to strike matches, are considered the most desirable, followed by those with only minor damage.

The value of a matchbook is also determined by its age, with older matchbooks being more valuable than newer ones.

My own little collection shown below is probably not worth more than a few $’s, but to me they were a surprise find in the back of a cupboard, and they brought back many fine memories.

Imposta Fiammiferi 'Minerva' - a special case

Two of my matchbooks were still sealed, one with a yellow Italian ‘Imposta Fiammiferi – Minerva‘, and the other with the green tax seal.

But what exactly were these “Minerva” matches and what did the tax seal mean?

The first match factory in Italy probably dates from 1831, but by 1845 there were at least 10 factories. Soon there was a consortium with around fifty large and small factories, employing around 6,000 workers. I saw mention of a factory in 1871 producing annually 35-40 billion matches.

In Italy, safety matches came in wooden boxes and even matches in cardboard boxes were seen as ‘fine articles’. A coarser and cheaper item was the zolfanelli or zolfini (also sulfonelli or solfini), which were sulphur-coated sticks with phosphorus-sesquisulphide heads, and were often sold in straw bags.

The luxury item, with limited consumption, was the “Minerva” match. In some countries, matches made of paraffined cardboard (“Minerva”) with heads without phosphorus were used. This was a strip of thin cardboard, which, folded and sewn in the middle, held a thick cardboard sheet, also folded in two, in which the matches were cut. The individual matches were not completely separated. They were arranged in two rows, and the flammable head was at the free end. These were ‘matchcovers’ (matchbooks) and were widely used, especially in Germany and North America, for advertising purposes.

I certainly don’t understand fully the history of Italian taxation on matches, but …

Originally the match represents a kind of basic necessity and being very widely consumed immediately attracted the taxation authorities in many countries. In may cases the state exercised both manufacturing and sales monopolies (on both tobacco and matches). Manufacturing could be through state factories or through concessions (coupled with a manufacturing tax), and sales through licensed outlets.

In Italy a manufacturing tax was applied in 1896, and collected through stamps applied to the boxes. In 1914 the tax represented approximately 35% of the prices for matches, but up to 50% for the imported ‘Swedes’ match. Importation was theoretically permitted, but the manufacturing tax stamps had to be applied to the boxes to be imported, and this operation had to be carried out at the Italian customs posts. So in practice the importation was almost impossible, as the goods could not withstand the increase in unpacking and reconditioning, and not forgetting the high tax and customs duties.

This system lasted until the end of 1916. On January 1, 1917, a sales monopoly came into force, enforced directly by the Italian state. The factories were no longer able to sell their product for internal consumption except to the state, which provided retail sales through the same organisation that handled the sale of salt and tobacco (the famous tabaccaio). Importation continued to be substantially prohibited, also because the state would have to be the buyer. Not surprisingly this buyer found domestic production superior and more conveniently priced than with foreign producers.

The Italian state monopoly lasted until 1923. From 1 June 1923 a manufacturing tax was reinstated. A consortium was set up, which included all the Italian match manufacturers. The Italian state then granted it the exclusive right to sell matches in the kingdom and in the Mediterranean colonies. The consortium provided for distribution and sale to the public, and the tax represented approximately 63% of the price paid by consumers, 69% for Swedish matches, 57% for sulphur matches, and 74% for “Minerva” type matches.

The Italian state also guaranteed a minimum price for lighters, so that the market for matches remained viable. It was in 1930 that the consortium took over also the monopoly on the fabrication, importing and sale of lighters. In 1956 the manufacturing tax for matches was transformed into a consumer tax (the monopoly on lighters remained intact). As one might have guessed, with the emergence of the European Economic Community it wasn’t long before such a monopoly had to be dismantled (by 1969).

Many countries around the world saw the convenience of charging a small excise tax on a box of matches. Usually the amount of tax was set in accordance with the number of matches per box, and in many cases even differentiating between local manufactured and imported matches. Most of the tax stamps were attached to the box by the manufacturers themselves, who generally did so by a manual process. There are collectors of match tax stamps, which represents a connection between phillumeny and philately. Revenue stamp collecting, especially of excise tax stamps, is one of the least known and studied fields of philately, which has traditionally focused on postage stamps. Regarding phillumeny, match tax stamps are included as the last on the list of “match-related collectables”.

Still in 1969 Italy received substantial income (manufacturer taxes) from profitable State monopolies on tobacco, salt, matches and cigarette paper. This was in addition to collecting sales taxes on everything from playing cards, spirits, beer, oil and gas, bananas, coffee, salt, sugar, margarine, olive oil, textiles and yarns, and of course including tobacco and matches.

With the introduction of the euro in 2001, a new decreto recorded the new prices for a total of 36 different types of matches and presentations. The lowest price was 0.15€ for 40 amorphous paraffined wooden matches in a cardboard mini-matchbox, and 0.20€ for 40 amorphous phosphorus paraffined wooden matches of the “Minerva” type. The most expensive was a cardboard box with 100 amorphous phosphorus waxed wooden matches called “Caminetto” costing €5.50 (these were matches used to light open fires).

From 2015 matches were no longer subject to a manufacturers tax, but immediately fell under the “Imposta sul valore aggiunto” (IVA), the Italian Value Added Tax. The tax, set at 15% at the time, had to appear on any payment receipt, invoice, etc. (today the IVA standard rate is 22% although I’m not sure what IVA rate is applied for matches). The legislation also removed the manufactures tax on tobacco, and was applied to both ordinary match products and those that were distributed free as advertising material.

Los Alamos and Las Vegas, May 1985

One of our first trips to the US was in May 1985. We arrived in Albuquerque, rented a car a drove up through Santa Fe to Los Alamos. It was a working trip, but we were also able to add a few days and visit Las Vegas.

Los Alamos is best known for its role as the site for the development of the world’s first atomic bombs, known as the Manhattan Project.

After the war the laboratory continued it work throughout the Cold War Era. The military base slowly turned into a town, with homes sold to private ownership. Finally, the gates to the Secret City came down in 1957, and the town was open to the public.

Still in 1985 Los Alamos was not well known, and the Los Alamos Inn was more or less the only hotel in the town centre. I still remember thinking that our compact rental car had some problems, but it was just losing power because the town is situated at about 2,200 metres.

I also remember having another problem with the rental car. When we arrived at the Los Alamos Inn, which really was a kind of motel, I couldn’t switch off the ignition and remove the key. I had to ask at the reception, and they showed me that to remove the key I needed to put the automatic in Park, and also press a special release button under the steering wheel (who would have known that). This was the first automatic I had driven, and the first sign that the US was (and still is) subtly different from the UK, and even more so from the rest of Europe.

Today, the location of the hotel is just a vacant building site. However Trinity Drive dates from the original military site, and at the time it was home to rows of barracks and dormitories, and yet at the same time some of the most “luxurious” living spaces on the Project. The Fermis, Bethes, Tellers, Allisons and other leading scientists lived in houses along Trinity Drive.

After our stay in Los Alamos we drove back down to Albuquerque, and flew to Las Vegas. The flight took around 100 minutes and was (and probably still is) a very cheap flight. At the time many people suggested driving, but despite being less than 700 miles, it would have been more like a 10-12 hour drive.

We stayed for 3 nights at Caesars Palace, and took a day trip to fly down into the Grand Canyon. I remember we had dinner in Caesars Palace, with staff dressed as Romans in short toga’s. I even had a neck and back massage given to me in the restaurant by a ‘buxom wench’, or the Roman equivalent. Monique was quite shocked.

We didn’t gamble, but Monique did play a slot machine. The ‘bet’ was a $1 bill and she immediately won $70, which we later lost playing red on one of the roulette tables. Nothing won, nothing lost.

Dallas, Chicago, New Orleans, and Washington, July 1991

This was a extended visit to the US covering several weeks, and the only free time was a couple of days we spent in Dallas (our return flight destination from Frankfurt). We stayed for a couple of days in the Fairmont in Dallas and visited the site of the assassination of JFK.

We also attended a conference (I was presenting several technical papers) and we stayed in the conference hotel, the Fairmont in New Orleans. This was one of the most tiring weeks I ever spent travelling. The conference was a full-on event, but in addition we played tennis on the hotel roof during the lunchtimes (in full July), and went out to Bourbon Street every night.

This trip included a visit to a major US equipment manufacturer near Chicago. They had their annual technical conference, which included a golf tournament. We stayed in the Nordic Hills resort, and played what is today called the Eaglewood golf course. We also had a separate round of golf at the Medinah Country Club, just next door. This club hosted the 2012 Ryder Cup.

I still remember being impressed with the John Hancock tower in downtown Chicago, and having a drink in the bar on the 96th floor.

Monique was struck by the very hot-humid conditions outside and the freezing air-conditioning in all the shops, etc.

This trip to the US also included a short hop to Washington (before returning to Dallas). It was quite a formal meeting, but it lasted only a few hours. We had dinner in our hotel, the Hyatt Regency Capital Hill, and ate a fantastic blackened steak in the foyer restaurant. This was our first visit to Washington, and would be the first of many. And we always stayed in the same hotel, and ordered the same dinner.

One of the tricks I used occasionally was to book a room using a conference rate, even if I wasn’t attending the conference. Unfortunately, on one occasion we turned up in this hotel, and found that the conference was of Black Methodist Ministers. This taught me to check what the conference was about before booking, but fortunately the hotel staff thought it was quite funny. Monique was less than amused.

Santa Fe and Kauai, November 1991

This was an official trip again to Los Alamos, but this time we decided to stay in the Eldorado Hotel down in Santa Fe.

We had also decided to try to add a ‘local’ golfing holiday to our trip. This was in the days before websites and review sites, etc. The reality was that planning an ‘add-on’ was complicated and expensive, but there was a way to arrange things differently. I contacted a local travel agent in Santa Fe and asked them about holiday trips that locals might take in November 1991. The two most popular options were Hawaii and Cancún in Mexico.

So we bought a local golfing package to Kauai Lagoons. Despite needed a connecting flight and taking 10-12 hours, it was still a US domestic package holiday. The whole week with the hotel, half-board, golf every day with buggy, etc. was very reasonably priced (by European standards), and the travel agent simply delivered our tickets, etc. to our hotel in Santa Fe.

When we arrived at the hotel we saw lots of publicity for something called the PGA Grand Slam of Golf. This was an invitational event contested by the year’s winners of the four major championships of regular men’s golf, which are the Masters Tournament, the U.S. Open, The Open Championship (British Open), and the PGA Championship. They played a kind of skins format with a total of $1 million on the table. The four golfers were Ian Woosnam (winner of the Masters), Ian Baker-Finch (British Open), Payne Stewart (U.S. Open), John Daly (PGA). Woosnam was the winner with $400,000, Baker-Finch came second with $250,000, while $200,000 went to Payne Stewart, and John Daly picked up $150,000.

With the competition running over two days, one of the courses was closed for a few days, but we had preferred tee times on the other course, so we had a very enjoyable golfing holiday. We also had access to the clubhouse, and saw John Daly at the bar, and Payne Stewart in the pro-shop. They were often joking about each other’s dress sense. We didn’t see Woosnam, who it was said arrived in his private jet and left immediately afterwards with his winnings. However, we did chat with Baker-Finch whom we found on the local beach with his family.

Amazing how a small piece of cardboard can bring back pleasant memories.

Later when travelling to New Zealand, we used the same idea and booked a ‘local’ holiday package for a week half-board on the island of Fiji. Trying to book this kind of add-on trip from Europe would have cost an arm-and-a-leg, but for a New Zealander it was a just a standard holiday package (other package options were the Cook Islands or the Australian Gold Coast) .

Washington and Hot Springs, May 1992

This was a one-week official trip to Washington, and we flew business class with Icelandair. There were very competitive prices offered for flights to the US, but with an obligatory stop-over in Reykjavík.

The business class trip included an all-paid two night stop-over with food (which was and still is very, very expensive), and a full-day visit to the island. Icelandair prices were very competitive, but if I remember rightly they flew in to Baltimore and not Dulles. In Washington we stayed (as usual) at the Hyatt Regency Capital Hill.

This time we had decided to make a major holiday of our trip. We visited many of the most important sights in Washington DC, and we had planned (but had not yet booked) to spend a week driving to and visiting Philadelphia (a 2-3 hour drive away). However the weather forecast was cold and rain.

In the Washington Post there was an ad for a full-board golf hotel in Hot Springs, with a daily round of golf included. The weather forecast for going south was much better than going north.

Prices were very competitive, and one of my contacts in Washington was a golfer and highly recommended the hotel. He went to the trouble of booking a full week for us through official channels (it was the US DoD). We didn’t have golf clubs, but the hotel confirmed that they would make available sets free of charge for us both (left-handed for me), and would include a buggy full time for our stay.

We had no idea what was waiting for us. Remember in 1992 there were no websites and online reviews, etc. All we had was a few people saying that it would be a great holiday, even if no one had actually ever visited Hot Springs, the hotel, or played the golf courses.

The drive of about 230 miles should have taken 3-4 hours, but it took 6 hours. We finally drove up at about 15:30-16:00, and saw a couple of grooms holding horses in front of the main entrance.

The hotel was The Homestead (now called The Omni Homestead Resort). Just finding a little collection of matchbooks from this hotel brought back a flood of memories. Many of them truly remarkable, and in many ways this hotel ignited our taste for the occasional luxury ‘experience’.

As we parked, staff came rushing out to welcome us. They knew our names, and we were expected. Everything had stopped for tea in the main lobby, a massive double-hight space full of columns. We spent an hour in the lobby having tea, sandwiches and cakes. People came and went to ensure that our golf tee times were correctly booked, that our spa visits were arranged, that dinner bookings were made, that our needs for breakfast were known, etc., etc.

Nothing so working class as passports and credit cards were needed, we were simply shown to our room. A very comfortable room but more low-key than over-the-top, true unobtrusive comfort. We found that our bags had been removed from our rental car, and everything had been unpacked and hung, etc. Everything dirty was sent for washing, and my suits (I had been attending formal meetings in Washington) would be cleaned and pressed for 18:00. Monique wore dress suits, and likewise her’s were also cleaned and pressed.

I did not see our rental car again until it was loaded with our baggage for our departure. They had also washed and cleaned the car.

We had a dinner reservation at 18:30 every evening in the main restaurant. Dress was formal, suit and tie. They made it clear, in a very friendly and discrete way, that we were expected to be punctual. Even Monique understood that!

I still remember being welcomed by name as if we were regulars. We had ‘our’ table, and Monique had a glass of champagne, naturally, being French. I was allowed to pick a drink, but it was assumed that I would, naturally, accompany my wife and drink champagne. I concurred. Deciding on what to eat was a leisurely experience, and at 19:00 the band started and we were expected to dance. They even had someone who would dance with my wife if I was ‘infirm’.

Dinner was served at 19:30, and it was perfect. Coffee and drinks were served in the lobby. Staff were quite shocked when I asked for a Italian-style expresso, but they managed a very credible offering, and there was a longish discussion on which bourbon would be best suited after such a strong coffee.

Our days passed in a pleasant haze of luxury. The type of luxury that is not asked for, but simple assumed. We played the Old Course because the first tee is the oldest in continuous use in the US. But we were also informed that they knew we would, naturally, prefer to play the more challenging course, The Cascades, for the rest of our stay. We had our buggy permanently available for us, with two complete sets of clubs, and including shoes, balls, tees, etc. In the afternoon Monique was whisked off for her massage, and I was shown the spa, sauna, etc. Clothes would disappear from our room and reappear cleaned and pressed, without us asking.

Hot Springs had been home to Sam Snead, and the hotels second restaurant was a more informal ranch-style restaurant with his name on it. I was informed that it was much frequented by groups of men playing the golf courses, but that it could be a bit ‘loud’ for the ladies.

One additional amusement, was that I was approached by a staff member wondering if I played tennis. They were over the moon when I said yes, more or less. A guest had asked if there was someone willing to play with him. They kitted me out with full tennis gear and equipment. In fact we had a great time since we were evenly matched. We dined together that evening, but they left the next day.

One final point, was something it took some days to ‘discover’. Firstly, not one guest was anything but a white American (except Monique and myself). No blacks, Asians,…, nothing, and no children. All the staff were African-Americans, and I never saw one of the staff sitting down. Still today I remember the two black grooms standing holding the horses when we drove up on our first day.

Some seven years later, August 1999, we would holiday in The Tides on Chesapeake Bay, and we would encounter almost the same situation. But this time with children, all dressed in jacket and tie, or dresses for the girls. The children were allowed to sit on the floor, and play with the hotels wooden toys, provided they did not make too much noise. In August most of the guests were from the New England states, and many had been coming to the same hotel since they were children themselves.

Amazing what memories a simple matchbook can re-kindle.

And back in Europe...

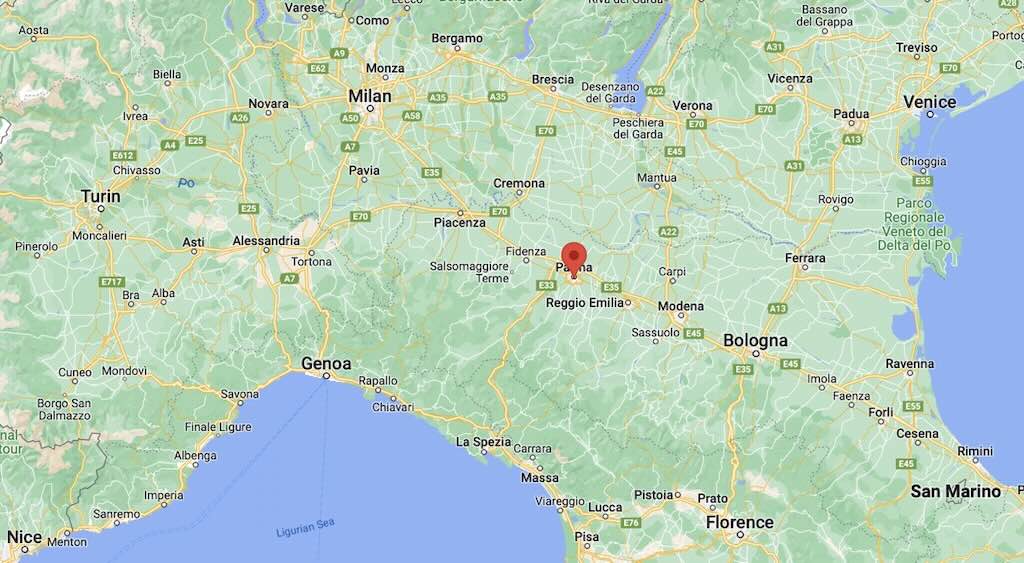

Just to show that matchbooks were not just a US advertising tool, here are a few matchbooks I picked up in Europe. Travelling around Europe during the period 1981 through to about 1995 I picked up numerous matchbooks, but I stopped when we had enough to light our open fireplace back at home. In 2007 when we moved house, the collection of matchbooks was relegated to the back of a cupboard in our new apartment (which didn’t have an open fire). It’s only in 2023 that I discovered our little collection, and decided to use them as a way to ‘re-kindle’ memories.

My impression was that advertising matchbooks were very popular with the smaller hotels in Germany, but it was also true that you could find them in the most out-of-the-way places, e.g. Crete, Burgos, Saint-Cyr-sur-Mer, and even Warrington.

Each of these places bring back memories. Jet skiing on Elounda Beach in November. Driving through Spain for the first time and visiting Burgos cathedral. Playing golf on the French south coast after visiting Monique’s mother in Nice. And having a safe and comfortable stop-over if I missed my flight out of Manchester (something that occurred more frequently than I would care to admit).