This particular post tries to look at the prehistory and protohistory of Luxembourg through the archaeological collection of the Nationalmusée um Fëschmaart.

Luxembourg’s national archeological collection was started in 1845, but it was only in 1939 that it found itself as part of a larger museum collection in the Maison Collart-de Scherff, situated in the Marché-aux-Poissons (the local fish market). Space was limited, but during the 1960s the museum grew substantially with the purchase of a series of houses in the neighbourhood. In 1996 it was decided to reorganise completely the museum, both in terms of space available and the need to give priority to the archaeological collection.

In 1997 a competition for the new museum was won by Christian Bauer et Associés, and the new building was inaugurated on 28 November 2002.

Until recently the Musée national d’histoire et d’art (MNHA) actually referred to both a cultural institute and a specific museum building. Recently, to give greater visibility to its substantial archaeological collection, the institute was ‘rebranding’ as the Musée national d’archéologie, d’histoire et d’art (MNAHA).

The MNAHA manages three museum sites and two research centres. The three museums are the Nationalmusée um Fëschmaart, the Musée Dräi Eechelen and the Villa romaine Echternach. The two research centres are the Centre de documentation sur la forteresse de Luxembourg and the Lëtzebuerger Konschtarchiv.

The building seen above is the Nationalmusée um Fëschmaart, which now explicitly refers to the original location of the fish market or marché-aux-poissons.

The archeological collection

The museum building actually consists of five floors underground and four additional floors above ground. The prehistory collection is on floor -5, and the protohistory collection on floor -4.

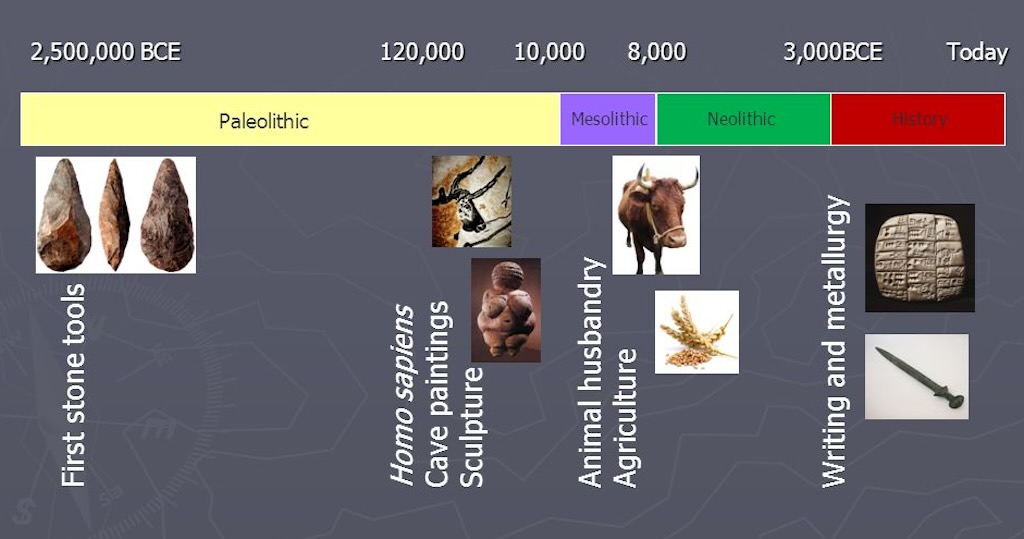

Prehistory is usually defined as the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins about 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. In the museum presentation they define prehistory as covering Paleolithic (1 million years ago through to 10,000 BC), Mesolithic (10,000 to 5,000 BC) and Neolithic (5,000 to 2,500 BC) periods. The periods are often called the early, middle and late Stone Ages, i.e. until the advent of metalworking.

Protohistory is the period between prehistory and written history, during which a culture or civilisation has not yet developed writing, but other cultures that had developed writing had noted the existence of those pre-literate groups in their own writings. For example, in Europe, the Celts and the Germanic tribes are considered to have been protohistoric when they began appearing in Greek and Roman sources.

Visiting the two lowest floors in the museum I was impressed with the overall presentation and the effort taken in describing the artefacts and how some of them fitted into the life of people living at that time. But I also found it a little too easy just to walk around looking at one or other object, and then leave without having a clear idea of how it all fitted into Luxembourg history. A problem of too much history concentrated into a small space.

Below I’ve tried to somehow fold what I saw into a story, illustrated with a few artefacts that caught my imagination.

If you get confused by some of the dates, period names, etc. here are a couple of graphics that can help.

Palaeolithic Luxembourg

Paleolithic Luxembourg (through to about 10,000 years ago) is less well understood than other more recent periods of Luxembourg history, but this may simply be due to the absence of any major excavations.

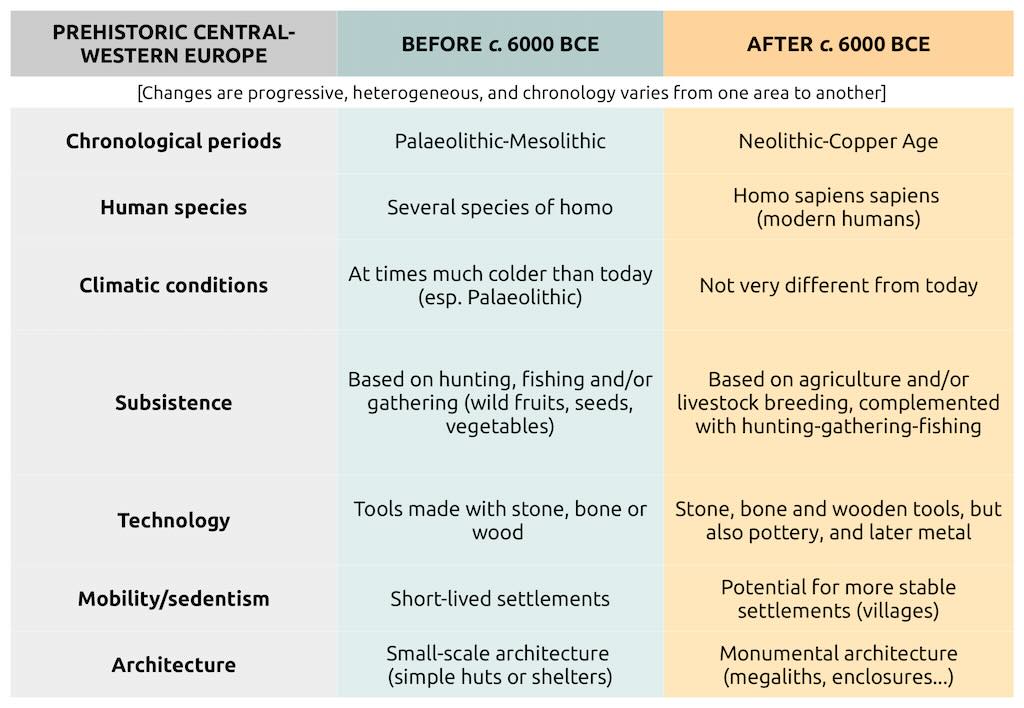

However, the rivers Moselle and Sauer (especially between Remich and Grevenmacher and around Diekirch) have yielded some pebbles with choppers, chopping-tools and the rare bifaces (or hand-axes). The problem here is that the lower slopes and alluvial upper terraces overlooking the valleys of the Moselle and Sauer have been subject to quite extensive erosion over time. The first ‘industries‘ in the region that can be really qualified as such are attributed to the penultimate glacial period, the Saalian (ca. 200,000-170,000 BC), a late phase of the Acheulean (ca. 1.7 million BC to 100,000 BC) culture.

Above we have the “Biface de Remich”, which is the most archaic tool discovered in the Grand Duchy. It was found by F. Schons in a place called Buschland, near Remich (which is in the Moselle valley). It is an amygdaloid (almond shaped) biface cut with large flakes. It is a reddish carmine quartzite sandstone, quite thin, and the distal end is broken.

My understanding is that the artefacts found on the middle terrace of the Moselle at Buschland point to a late phase of the Acheulean culture (so sometime between 300,000 to 130,000 years ago). Most of the pieces found there were made from slabs of purplish Devonian quartzite known as ‘Taunus‘, a siliceous rock outcropping in a primary position in the South-East of the Grand Duchy. What were found were poorly standardised flake tools and a few rare bifaces, most attesting to the use of the Levallois technique (peak usage ~200,000–40,000 years ago), which involved the striking of lithic flakes from a prepared lithic core, and usually associated with the Middle Palaeolithic.

There is quite some evidence that the nomadic hunter-gatherer Neanderthals (not yet modern man, but living between ca. 600,000-30,000 BC including proto-Neanderthals) spent sometime in Luxembourg.

They left traces, ‘industries’, throughout the entire territory of Gutland (southern and central part of Luxembourg) and on the steps of the Ösling (northern part of Luxembourg), near the Ardennes. The kinds of artifacts found are worked pebbles of quartz and quartzite, similar to what have been found in the French Lorraine and the Palatinate, Hesse and the Middle Rhine in Germany.

Stones were selected because of their flat or circular form, and were knapped using the Levallois technique (an early sign of mass-production of standardised tools). There were flint Mousterian tools (e.g. points and scrappers dating from ca. 300,000 to 30,000 BC) favoured by ‘Homo neanderthalensis‘. Evidence found in France indicates that Neanderthals were also making the lissoir from bone some 50,000 years ago. This was a kind of ‘smoothing’ scrapper used for cleaning skins and making them leather-like. It would appear that Neanderthals developed their own technologies, and may even have passed this particular one on to the modern man. Anyway given the erosion in the river basins it has been very difficult to put an exact date on many of the artefacts found on the terraces.

There are some traces in Luxembourg of a Middle Paleolithic industry (ca. 300,000-30,000 BC), the Micoquian (ca. 130,000 to 70,000 BC), characterized by small lanceolate (leaf-shaped) bifaces or hand-axes, found in Altwies, Bourglinster, Gonderange, and Remich.

Also flat, heart-shaped hand axes, probably Mousterian, have been found in places such as Altwies, Bettendorf, Christnach, Echternach, Hesperange and Lellig. And finally Charentian (a Mousterian variant or sub-division) side scrapers and Quina-type hand tools that had both undergone many alterations, some denticulated, and even some stone knives, have been found in Frisange, Hellange, and Manternach.

The oldest artifacts from this period are decorated bones found at Oetrange, important in that they demonstrate that man started to have spiritual and artistic interests that would eventually lead to burial rituals.

Moving into the Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 10,000 years ago), or late stone age, the Luxembourg region would have witnessed the emergence of Cro-Magnon (an early modern human from perhaps 43,000 years ago), the arrival of early modern man Homo sapiens in Europe (ca. 30,000 years ago), the extinction of the Neanderthals (c. 30,000-22,000 years ago), the emergence of organised settlements or campsites, and the appearance of flint tools for hunting, fishing and processing prey.

In addition, of course, there was the Ice Age, or more specifically the last glacial period lasting from ca. 110,000 to 10,000 years ago. Luxembourg would certainly have been affected by both the so-called Weichsel (Weichselian) glaciation and the Würm glaciation in the Alps. The weichsel glaciation was at its most intense some 23,000 to 13,000 years ago, and may well have also seen as many as 8 interstadial periods (a warmer period between a stadial or period of lower temperatures). The Würm glaciation was also at its most intense between ca. 24,000 to 10,000 years ago.

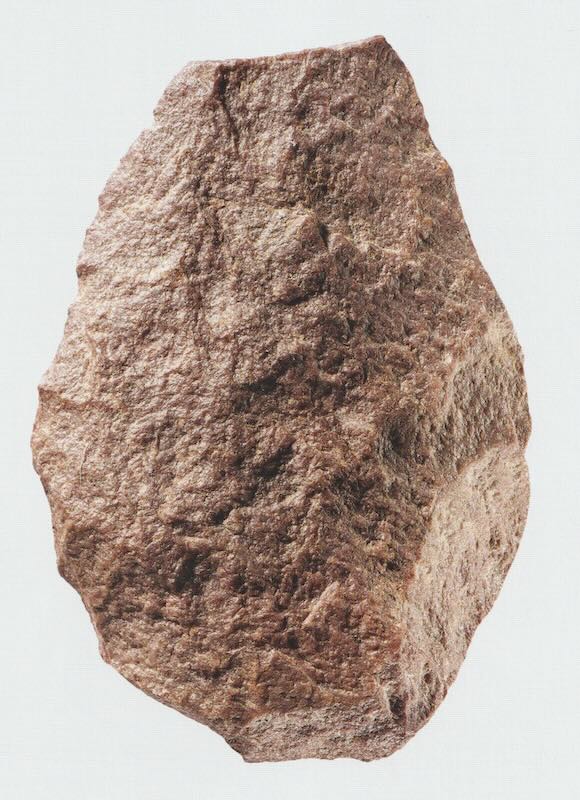

These massive ice fields ‘trapped’ a large area of south-west France, northern Germany and central Europe, including Luxembourg, turning it into an open steppe–tundra. The herbaceous vegetation typical of this very cold, dry climate provided good feeding for mammoths, horses, bison, giant deer, aurochs (a type of extinct cattle) and reindeer.

Above we have a casting of a woolly rhinoceros head found in Mertert-Wasserbillig, a small town in eastern Luxembourg.

Herds would have been mobile and early man, the hunter-gatherer, would have followed them. He would have had to develop some type of clothing from pelts, find or construct shelters with hearths to cook meat (started to appear 250,000 years ago), and learn how to dig ‘ice cellars’ for storing meat.

Modern man would also have started to have aesthetic concerns, creating sculptures, engravings, paintings and even rudimentary musical instruments. Below we have the earliest “artistic” work found in Luxembourg, the polished and incised bone fragment of a deer and an incised bears tooth found in Oetrange “Kakert”.

In fact numerous bones belonging to cold fauna have been discovered on the lower terrace of the Moselle between Mertert and Wasserbillig. In addition several flint tools characteristic of various Upper Paleolithic cultures have been found on the tops of the sandstone plateau’s of Luxembourg.

These natural promontories would have offered excellent lookout positions to monitor the movement of game in the valleys. However, it’s not clear that there would have been any permanent occupation of the Luxembourg region at that time. Firstly there were major temperature oscillations (check out the Allerød oscillation between ca. 14,000-13,000 years ago and the following Younger Dryas period between 12,800 and 11,500 years ago). This period even saw the resurgence of reindeer in the Ardennes and Eifel (ca. 11,800-10,200 years ago). In addition there was the eruption of Laacher See (ca. 12,900 years ago) in the German Eifel which is said to have killed all plants and animals in a region of 40-60 kilometres, and affected an area of perhaps as much as 300,000 square kilometres, including Luxembourg.

It’s nice to imagine large herbivores such as the Wolly Mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), Steppe Bison (Bison priscus) and the Woolly Rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) roamed the Luxembourgish open steppe-tundra, feeding on grasses and shrubs. Rubbing shoulders with large carnivores such as the Cave Lion (Panthera spelaea), Grey Wolf (Canis lupus), and Cave Bear (Ursus spelaeus).

As the climate started to warm up (ca. 12,000 years ago), several competing groups would probably have passed through the Luxembourg region. We know of at least two groups that were active in the Eifel region, the Federmesser (ca. 12,000-10,800 BC) with their arrow heads, and the Ahrensburgian (ca. 11,000-10,000 BC), nomadic hunters who are said to have been the first to use the bow and arrow rather than the javelin because of their improved accuracy.

If we would have stood and watched we would have seen “modern man” start to use tools and technology such as the microlith, small flint tools often used with throwing weapons such as spears and arrows. And we would have seen his natural pray, the reindeer and bison, withdrawing to the north, leaving him with non-migratory wildlife such as deer, boar and aurochs. Finally we would also have seen the extinction of the Ice Age mega-fauna such as the woolly rhinoceros, the Irish elk, the cave bear, the cave lion, and the mammoth.

With climate stability, the growth of natural woodland and a non-migratory wildlife, man would have been forced to adopt new weapons and hunting strategies. Rock shelters became the ideal, groups and clans could grow more numerous, and coded funeral rites and practices appeared.

For example, Johannes Steiniger (1792-1874) found in a naturally formed cave called “Buchenloch“, near Gerolstein in the Eifel, stone tools and animal bones of the mammoth, cave bear, wild horse and reindeer. Other caves, such as the “Kakushöhle” near Eiserfey a district of Mechernich, and the “Genova-Höhle” in the region of Kordel confirmed these findings. There are clear indications that these naturally formed caves were visited by both Neanderthals and “modern” reindeer hunters ca. 12,000 years ago.

Below we have a reconstruction of the “Loschbour” burial.

For Luxembourg the excavations performed in the 1930’s concerned only rock-shelters located in the immediate vicinity of the Black Ernz in Gutland, and the site Reuland “Loschbour” in the municipality of Heffingen.

An almost fully-formed human skeleton was unearthed by Nicolas Thill, native of Heffingen, on October 7, 1935. This is so far the oldest known prehistoric tomb in Luxembourg. In fact there was both a burial (Loschbour I), and a cremation nearby (Loschbour II). The skeleton was buried in an extended position, lying on his back, forearms folded and crossed over the chest. Two fragments of an aurochs’ ribs were placed next to the thorax (meat offerings?), and a small round flint was found inside the skull (Viaticum?). It looks to have been a voluntary burial. The deceased was a strong adult man with strong muscles and 160 cm in height.

Nearby some fragments of another single individual human were also found. The burn marks and traces of flint marks on the bones suggest a cremation. Among the remains was an item of adornment, a drilled fossil shell. “Loschbour” is commonly known as the oldest Luxembourger!

As one expert noted, Loschbour Man lived on the cusp of the Neolithic age, which had begun in the Middle East with the development of agriculture around 10,000 BC.

Recently the skeleton has been dated to between 6220 and 5990 BC (e.g. some 8,000 years ago). He almost certainly had dark hair and blue eyes, and his skin was darker than the average present-day Northern European. He was around 160cm tall, he weighed about 60kg, and he died between the ages of 34 and 47.

Buried alongside Loschbour Man were a number of flint weapons that would have been used to kill deer and wild boar, and this information pointed to his method of subsistence, he was a hunter-gatherer, not a farmer. This hypothesis was confirmed by analysis of Loschbour’s DNA, he had a low-carb diet and was lactose-intolerant, unlike 90% of modern Europeans. So he had a meat diet based on terrestrial game (mainly wild boar and deer), and we also know that he suffered from mild osteoarthritis.

The DNA from his upper molar also confirmed that he descended from hunter-gatherers of central and eastern Europe (who spread throughout Russia, Germany, Sweden, England, Spain, and Luxembourg during the period ca. 9,500-5,000 BC).

He probably did not know it but his days were numbered. His haplogroup was U5a, which can still be found today in about 10%-11% of Europeans, but he was nevertheless destined to be replaced by the people of the Linear Pottery Culture (ca. 5500-4500 BC), a culture strongly linked to the spread of agriculture (often also called the Danubian culture). It is possible that these early farmers were of the haplogroup N1a with its origins in the near east. They might well have pushed our early Luxembourger into extinction (he had more or less disappeared by ca. 4500 BC), but these early farmers were also destined to disappear, because their haplogroup currently appears in only 0.2% of European populations. Tracking Neolithic and Bronze Age migrations through Europe is a fascinating topic, that is worth checking out in this series of maps running from 8,000 to 3,000 years ago.

In fact the Late Mesolithic genome from the Loschbour skeleton remains a benchmark for ancient DNA studies, and serves as a high-quality reference genome (approximately 22× sequencing depth) for the Western Hunter-Gatherer population that lived in Europe before the arrival of the first farmers. Genetic studies in the Blätterhöhle in Germany, roughly 200km from Luxembourg, indicate that farmers and foragers would later live side-by-side for centuries.

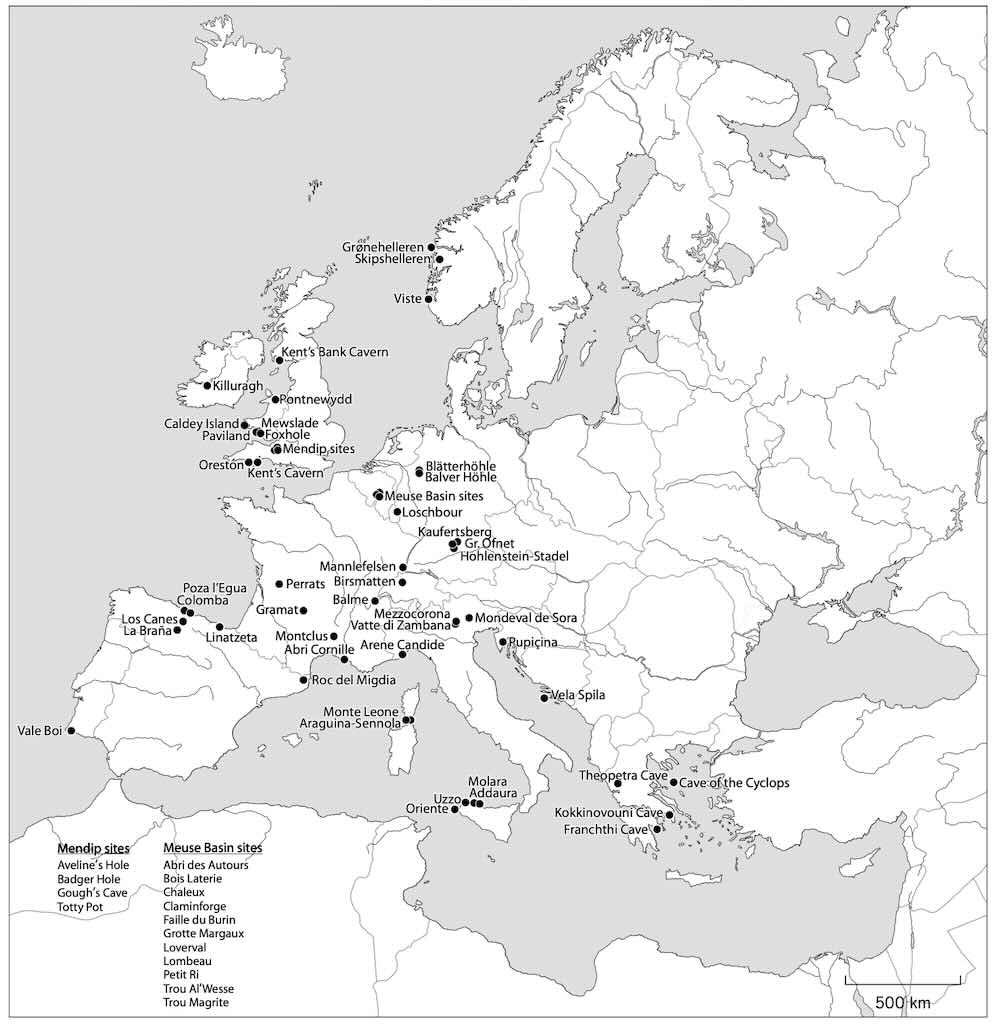

Above we can see a selection of cave sites with Mesolithic human remains that have been directly dated or were found in a secure context (including Loschbour).

Of course this cave burial practice does not begin in the Mesolithic, but extends back into the Upper and Middle Palaeolithic, however, only in a very small number of caves is there even the suggestion of continuity in their use from the Late Pleistocene into the Holocene (the somewhat arbitrary division between Palaeolithic and Mesolithic). In fact it is by no means clear that people in the Mesolithic were aware that the cave had been previously used for burial, and so the presence of human remains from both periods may be entirely coincidental.

It’s also worth noting that caves often preserve archaeological material, including burials, better than open-air sites, and have received more attention, not only from archaeologists, but also from recreational cavers who have been responsible for many discoveries.

Finally it’s interesting to note that most human remains of whatever period tend to be found either not far from the entrances of large caves, or in small, shallow caves and rock shelters. Placing burials near the entrance might have emphasised the transitional nature of the entrances, and so can metaphorically speak of the transition from life to death. Where bodies were left on cave floors, the place in the cave might have been a compromise between the cooler temperatures and protection from the elements, and yet still having enough light (and air given the smell) to see the remains.