This post is about the odd topic of “Mattering“, and derives from a podcast I heard in early 2026 with Rebecca Goldstein.

I had never heard the word before, but Wikipedia tells us that “mattering” is a psychological human need. A person matters when they are not only contributing to others, but also feels valued for that contribution. The sense of mattering can be considered in terms of mattering to a specific person, and to other individuals, and also to society at large.

Mattering is related to, but distinct from, belongingness, self-esteem, and social connection. It is a core component of each person’s self-concept. A person’s well-being depends in part upon a sense that they matter to someone. People who feel like they matter have more psychological resilience.

The podcast covered a vast area, and I can’t promise I captured the real meaning. But it argued that mattering was a necessary component for someone to feel well about themselves. It more than just being in a group, “it being missed if you weren’t there”. When it comes to self-esteem, you can like yourself and feel capable, “will people notices you when you enter a room”?

Some people see mattering as being valued, appreciated and cared for, others see it as feeling capable, important and trusted.

The French have the expression “être bien dans sa peau“, meaning to feel comfortable in one’s own skin, being at ease with oneself, or feeling good about who they are.

I didn’t really buy into that at a personal level. I felt my wife mattered to me. I might even define love as the many ways of mattering to someone. And I knew that I matter to her.

Wikipedia defines Love as an emotion involving strong attraction, affection, emotional attachment or concern for a person, animal, or thing.

The Psychology of Mattering

In psychology, mattering refers to the perception that one is noticed, important, and has an impact on others. Whereas love is seen as a bond involving attachment, care, and attention to the well-being of another. Aristotle went on to apply his theory of hylomorphism to living things, saying that a soul is related to its body as form to matter.

I liked the idea that mattering is a tangible expression of love, and creates a feeling of safety and belonging. If you love someone, you must show them they matter. And if you are loved, you must feel that you matter to them.

Matter - The Mother of Invention

In the podcast the origin of the word “matter” was discussed. Wikipedia has a short entry on the philosophy of matter as the branch of philosophy concerned with issues surrounding the ontology, epistemology and character of matter and the material world. It mentions that Aristotle developed a theory of matter and form, which was known as Hylomorphism, which argued that every physical entity or being (ousia) is a compound of matter (potency) and immaterial form (act). The word is a 19th-century term formed from the Greek words ὕλη (hyle: “wood, matter”) and μορφή (morphē: “form”). In fact the Ancient Greek language originally had no word for matter in general, as opposed to raw material suitable for some specific purpose or other, so Aristotle adapted the word for “wood” to this purpose. Aristotle defined matter as “that out of which” something is made. For example, letters are the matter of syllables, clay is matter relative to a brick because a brick is made of clay, whereas bricks are matter relative to a brick house. Equally bronze is matter, and can lose one form (morphe) (that of a lump) and gains a new form (that of a statue).

Latin thinkers opted for a word that had a technical sense (rather than literal meaning). In Latin materia was “wood”, not metaphorically but literally, as in the physical wood used for building. And the word materia was chosen to indicate a meaning not just in handicraft, but in the passive role that mother (mater) plays in conception.

There was also a mention of the pre-latin roots, where its suggested that in a proto-Italic reconstruction, *materjā- or *materjām (forms vary depending on reconstruction tradition) relate to a proto-Indo-European root *mater- (“mother”). So very simplistically “mother” was the biological origin/source of Man, wood/timber the origin of a constructed object, and material/substance the origin of a thing’s form or function. So materia was “the mothering stuff,” i.e., that-from-which-a-thing-is-made.

The Verb “to matter”

Turning to matter as “to be of importance” or “to be relevant”. Historically (1225-1300), “to matter” originated from the idea of having substance, having content, or being the stuff a thing is made of. As a verb, matter appeared in English in the 1420-1450, in the sense of “to be of consequence” or “to be important”. An example is how matter (noun) meant “subject or issue” (e.g. “a matter of law”), to matter (verb) meaning “to have significance” (e.g. “it matters to me”).

The Podcast

I’ve listened to the podcast twice, and I fell that there is something worthwhile in it, but I could not isolate what it was.

So I gave the transcript to ChatGPT, and asked for a summary (shown below unedited). Sometimes ChatGPT can be really stupid, but this time, good or bad, its summary is far better than i could have produced (and it took 5 seconds).

1. Context: Naturalism and “Mattering”

Sean Carroll (the podcast host) starts by situating the conversation in his long-standing interest in philosophical naturalism:

-

Naturalism = the view that the universe is just physical stuff obeying laws, with no supernatural beings guiding or valuing us.

-

He notes that earlier public debates (around 2012) focused on “religion is wrong / harmful”, but that’s the “easy part.”

-

The harder, more interesting part is: given naturalism, how do we deal with questions of meaning, morality, purpose, and value?

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein has been thinking about one central piece of this puzzle for years: mattering – what it means to say that something (or someone) “matters”.

Her new book is The Mattering Instinct: How What We Have in Common Drives Us and Divides Us.

2. What Is “Mattering”?

Goldstein distinguishes between:

-

What matters – things, projects, values.

-

Who matters – persons, groups, beings.

Her core definition:

To matter is to be deserving of attention.

That definition already contains something “normative”:

-

“Deserving” implies justification, reasons, standards.

-

So human beings are not just physical systems; we are normative creatures who worry about whether we oughtto pay attention to ourselves and others, not just whether we in fact do.

This concept of mattering isn’t tied to any particular moral theory (objectivism vs subjectivism); it’s a descriptive starting point:

-

Humans everywhere try to justify their lives to themselves.

-

We construct “mattering projects” that support the sense: “I’m justified in paying so much attention to my own life.”

3. Two Fundamental Human Needs

She refines Freud’s “love and work” into two more specific needs:

-

Belonging / Connectedness

-

We are gregarious and altricial (helpless for a long time after birth).

-

We need others who will give us special attention whether we “deserve” it or not: parents, family, friends, lovers, colleagues, community.

-

This is a form of social mattering – mattering to others.

-

-

Self-Mattering / Justifying Ourselves

-

We are stuck living inside one mind that pays an enormous amount of attention to itself.

-

Depression, she says, often feels like a “psychic autoimmune disease”: you can’t stand living with yourself; you feel you don’t deserve your own attention.

-

The central existential question becomes:

“Am I worthy of all this attention I cannot help but pay to myself?”

-

Both needs are distinct but deeply entangled:

-

We can have social bonds yet still feel existentially empty (e.g., William James; his sister Alice).

-

Or we can be successful, admired, even famous, and still feel we don’t matter in the way that matters to us.

4. From Physics and Biology to Mattering

Goldstein ties mattering to entropy and evolution:

-

Second law of thermodynamics: closed systems tend toward increasing disorder (entropy).

-

Life is defined by resistance to entropy: organisms use external free energy (food, sunlight, etc.) to maintain and increase internal order.

From that:

-

Every living being has a basic conatus (Spinoza’s term): a drive to persist and flourish in its own being.

-

With evolution of attention and theory of mind, humans became capable of:

-

Tracking what in the environment affects their survival and flourishing.

-

Recognizing that others have minds, beliefs, desires.

-

Turning that same capacity back on themselves: self-reflection.

-

Self-reflection plus self-concern gives rise to the mattering instinct:

-

We see the huge gap between how much we naturally matter to ourselves (we’re our own central project) and how much we think we objectively deserve to matter.

-

We respond to that gap by building mattering projects to make the two more commensurate.

5. Four Main “Mattering Strategies”

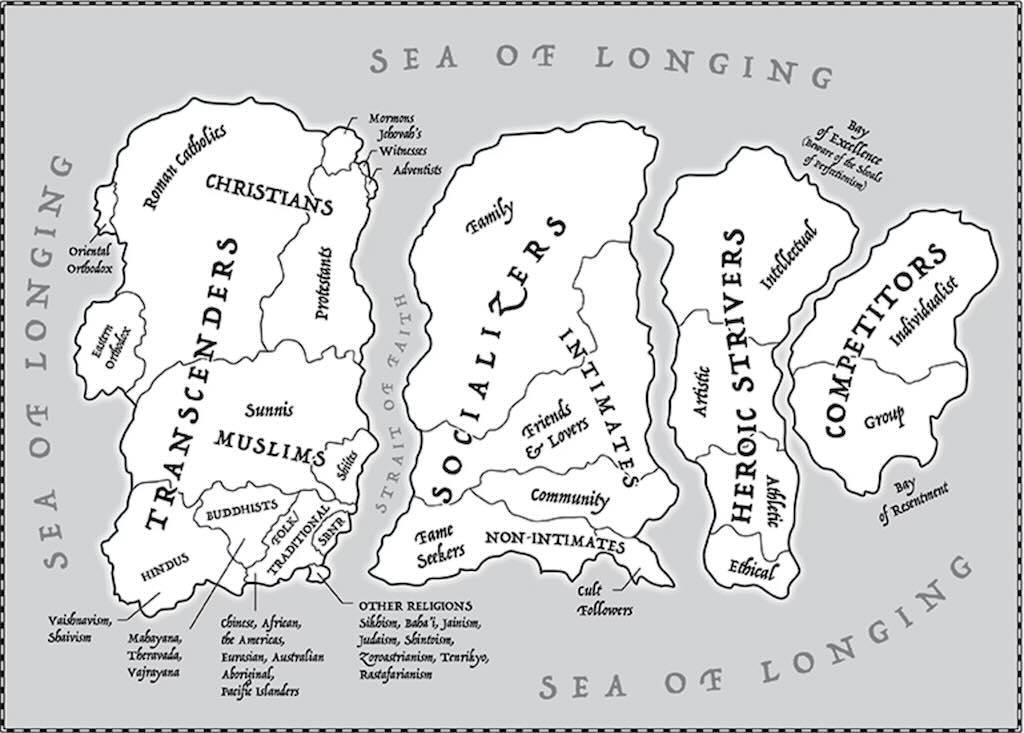

From talking to many people (from pickup artists to ex-Nazis), Goldstein identifies four broad strategies or “continents” on the “mattering map” – the landscape of human ways of mattering:

-

Transcendent / Cosmic Mattering (Transcenders)

-

We matter because a higher being (God, etc.) created us with a purpose.

-

We have a role in an eternal narrative.

-

This is common in religious and spiritual worldviews.

-

It seems less plausible under naturalism, but it is a very powerful way of satisfying the longing to matter.

-

-

Social Mattering (Socializers)

-

Intimate socializers:

-

Mattering = mattering to close others (family, friends, partners, community).

-

Belonging and mattering are essentially the same thing.

-

-

Non-intimate socializers:

-

Mattering = mattering to crowds or strangers (fame, followers, being admired).

-

Example: celebrities, cult leaders, those who want “everyone to know who I am”.

-

-

-

Heroic Striving (Heroic Strivers)

-

Mattering = living up to a standard of excellence:

-

Intellectual, artistic, athletic, moral, etc.

-

-

The aim often isn’t primarily to be admired; it’s to be worth admiring by one’s own lights.

-

You can be famous and still feel you’ve failed; fame alone doesn’t secure mattering.

-

Many scientists, artists, writers—and Goldstein herself—see themselves here.

-

-

Competitive Mattering (Competitors)

-

Mattering = mattering more than others; a zero-sum view.

-

For me to matter more, others must matter less (individually or by group).

-

This fuels power-seeking, status struggles, and some forms of bigotry.

-

Her ex-Nazi friend originally grounded his mattering in being a white American male whose status he felt was being “stolen” by others; later he transformed into an ethical heroic striver.

-

People often mix these strategies, but usually one or two dominate.

6. The “Mattering Map”

To make this more concrete, Goldstein introduces the metaphor of a mattering map:

-

A conceptual map with four main continents:

Transcenders, Socializers, Heroic Strivers, Competitors. -

Within each continent are many regions:

-

The “pickup artist” region, the “Tupperware enthusiast” region, the “fashion as salvation” region, etc.

-

-

Each of us lives in some region of this map:

-

Our co-inhabitants share similar views of what counts as a life that truly matters.

-

Conflicts often arise when people from different regions universalize their own way of mattering.

-

The map idea originally came from one of her fictional characters (a Princeton philosophy grad student) who says, “I don’t matter in the way that matters to me” — and that line helped Goldstein crystallize this whole framework.

7. The Urge to Universalize (And Why It’s Dangerous)

Across all four strategies, humans tend to universalize their own standard:

-

“This is what makes my life matter; therefore this is what a meaningful life is.”

-

Religious transcenders universalize theological standards.

-

Heroic strivers (academics, artists, etc.) often assume everyone ought to be creative, original, productive, etc.

-

Socializers may assume everyone should prioritize family or community.

-

Competitors universalize rankings and dominance.

Goldstein’s key point:

-

There is not one single right way to matter.

-

However, that does not imply moral nihilism or “anything goes.”

8. Right vs Wrong Ways of Mattering (Back to Entropy)

She proposes a principled distinction:

-

Life itself is a counter-entropic process: it maintains and builds order.

-

Some mattering projects are aligned with this:

-

Creating and sustaining knowledge, justice, beauty, fairness, community, care.

-

These projects build structures of order and value that are hard to create and easy to destroy.

-

-

Other projects are misaligned:

-

Aggression, conquest, domination, cruelty, exploitation, destructive narcissism.

-

These increase disorder, suffering, and breakdown—often on a large scale (Hitler, Putin, Leopold, Trump as examples).

-

So:

-

There are many legitimate, diverse ways of mattering.

-

But some ways are objectively bad because they attack the very counter-entropic, life-promoting order that makes any mattering possible.

9. Psychological Robustness and Fragility

Among heroic strivers especially, she notes a difference:

-

Some people find a mattering project that just carries them: they rarely question their worth; they just keep going.

-

Others (like William James, and Goldstein herself) repeatedly face crises of mattering:

-

When a project falters, their sense of worth falters with it.

-

This can drive depression, but also ambition and creativity, as they search again for a way to matter.

-

This variability—how robust or fragile our mattering is—shapes the trajectory of lives.

10. Political and Ethical Stakes

Goldstein closes on the political implications:

-

One of the deepest problems of our time:

“How can we recognize that we are not all alike without wanting to wring each other’s neck?”

-

Liberal democracy presupposes exactly that:

-

Different ways of living and mattering must coexist.

-

We need to respect that diversity without collapsing into “everything is equally fine” or into “only my way counts.”

-

So her conclusion:

-

There are many right ways to matter; no one has a monopoly.

-

But there are also wrong ways—those that harm others, destroy order, and treat mattering as purely zero-sum.

-

Understanding the mattering instinct, the mattering map, and our own particular location on it can:

-

Help us navigate our personal lives (what really matters to me),

-

And help us understand others with less contempt, more clarity, and better ethical judgment.

-