My beloved wife Monique passed away on 23 December 2023. So I was now faced with making “our” Spring Roadtrip 2024 south to Andalusia by myself.

My third stop was at the La Galiana Golf Resort in Barraca de Aigües Vives, about 55 km south of Valencia in Spain.

As usual when making a long trip north or south, my choices are largely determined by location, i.e. in the right place to spend a night as I drive to southern Spain or return north. I always look for free secure private parking, free wifi, a shower (not a bath) and an evening meal.

Booking gave this hotel an 9.4/10 (Fantastic) from 300 reviews, and Tripadvisor gave it a 4.5 from 21 reviews.

I very much enjoyed my stay, and I expect to use this hotel in the future because it’s ideally located about a 6-7 hour drive (approx. 700 km) from my base in southern Andalusia.

In fact during my Summer Roadtrip 2024 I did again spend one night in this hotel, and my comments are included at the end of this first review.

Finding the hotel

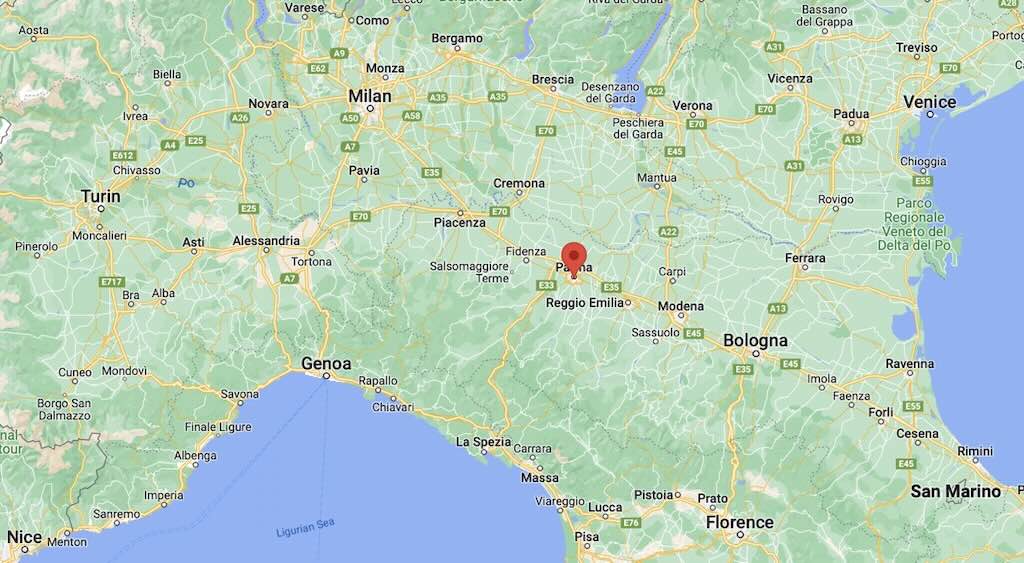

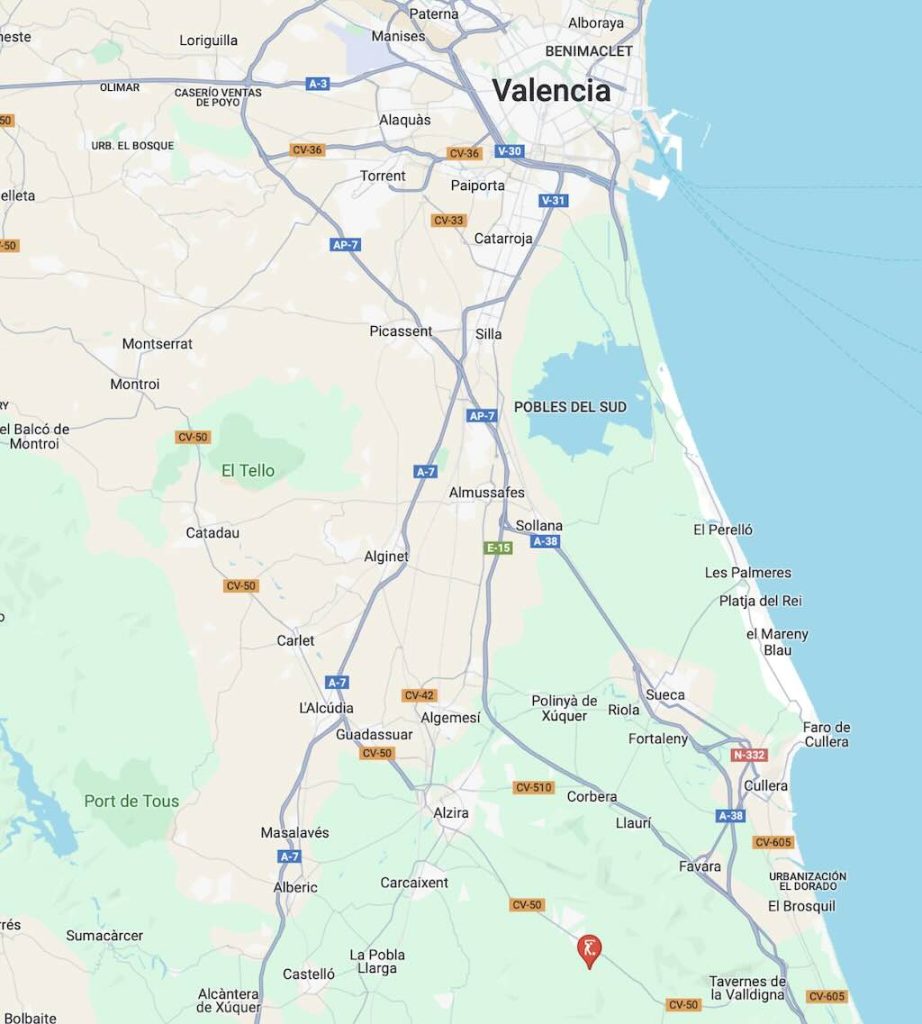

Above we can see that the La Galiana Golf Resort is inland, about 55 km south of Valencia. My GPS took me on to the CV 50, a Valencian regional highway that goes from Tabernes de Valldigna to Liria, both in the province of Valencia. It is a comfortable route but you have to have confidence in the GPS otherwise you begin to think you have missed a turn. The golf course and hotel are set behind a residential area that surrounds the Hospital Vithas Aigüas Vives.

The Galiana Golf Resort is signposted, but again you have to have confidence. The signposts will eventually bring you to the main entrance of the resort, with one road to the golf club and another to the hotel.

The geography is interesting

The Aigües Vives valley is located in the Ribera Alta region, province of Valencia, bordering the La Valldigna subregion. La Valldigna is a horseshoe shape valley bordered by mountain ranges (Baetic System and the Sistema Ibérco) on the west and the Mediterranean Sea to the east.

The Aigües Vives valley is part of a series of parallel valleys, along with those of La Casella and La Murta, with a northwest-southeast orientation that are part of the last foothills of the Sistema Ibérco.

This area, little known to tourists, is one of the emblematic enclaves of Valencian geography. It is subject to a very favourable microclimate, with mild temperatures and a high degree of humidity. In these conditions, plants develop and mature quickly. We find flowering ash trees, holm oaks, hawthorn, laurel groves, strawberry trees, durillos and myrtle trees, a species that gives its name to one of its valleys.

The Aigües Vives valley is the largest of them, delimited by the Sierra de las Agujas, with steep slopes and a maximum height of 553 meters, and the relief of the Realenc-Falzia, much gentler. The Barranc de l’Estret marks the valleys lowest point. It collects groundwater and numerous springs from the Barranc de la Falzia and the slopes of the valley.

Today the valley is often seen as a green space, the “lung” of Alzira. It is of great ecological value since it still maintains important forests of pine and scrubland.

One increasingly popular tourist attraction in the region is trekking, with at least seven different walks ranging between 3 km and 26 km (an easy 90 minutes up to a hard 7 hours).

Agriculture is important, especially citrus, which is practically a monoculture. Small properties predominate (minifundismo), which are plots exploited by the same person responsible for the management, whether or not its owner. The exceptions are the old family estates, some of which are devoted to rice-growing. Livestock farming is practically non-existent, and there are no industries in the valley.

The orange

The orange is the fruit of the citrus sinensis or aurantium, a tree that first appeared in China and other southern areas of the Asian continent. The fruit made its way from the Far East to the European continent, reaching Spain, through Valencia, and then spread throughout the rest of the world. When Arabs brought orange farming to the Iberian Peninsula, they called the fruits naranjah.

The Region of Valencia maintained the orange-farming tradition after the Arabic period, with references to orange trees in the city of Valencia dating back to the 14th century. In fact, there is an Orange Courtyard inside Valencia’s 15th century Silk Exchange market (La Llotja de la Seda), a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

At present, there are approximately 150,000 hectares of orange groves in the region around Valencia producing orange and mandarin varieties including satsumas, clementines, navel oranges, blood oranges, and a variety of hybrids.

The area has quite a history, but its origins are a little uncertain

The first reliable document show James I of Aragon (Jaime I 1208-1276) granting a certain García de Massa the farmhouse of “AquaViva”. which stood at the same place where the urban centre of ‘La Barraca’ is today.

A barraca is a traditional Valencian gable–thatched farmhouse, and along with the paella and horchata, constitutes one of the symbols of the city of Valencia.

The presumption is that this farmhouse was located in part of the valley where the vegetation would have been the most exuberant and where a large number of springs converged. In 1329 the farmhouse and associated land became the property of the nearby convent of the Augustinians.

Naturally there are also undocumented stories that in the year 826 the Moors desecrated a convent of the order of Saint Augustine. Some monks took refuge on the island of Formentera, but others hid in the mountains and deserts of Aguas de Busot Vives until 1239, when Jaime I founded the convent with the title of Monasterio de Agua Viva (Monastery of Living Water).

In 1450, King Alfonso the Magnanimous, from Naples, granted a privilege to the convent creating a “Dehesa”.

A “dehesa” is a type of agroforestry, or land that was fenced and usually destined for pasture. Used primarily for grazing, they produce non-timber forest products such as wild game, mushrooms, honey, cork, and firewood. They were also used to raise the Spanish fighting bulls and the source of jamón ibérico, the Iberian pig.

In 1595 Philip II granted a royal privilege that ratified what had been granted by Alfonso V.

Eventually the Augustinians of Valencia would built a new farmhouse, but the place would keep the name La Barraca. However, the valley continued to suffer from a shortage of labour, so around 1701 it was decided to encourage new settlers by offering a little land on which to build a house. But the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) would later devastate the entire valley.

The Convent d’Aigües Vives (in Valencian) is also known as the Royal Monastery of Santa María de Aguas Vivas (Reial Monestir de Santa Maria d’Aigües Vives). It is a religious building whose origins date back to the 13th century, but the current building was built during the 16th and 17th centuries, although the north wing was completed only in the 18th century. The monastery belonged to the Augustinian order, but in the mid-19th century, as a result of the confiscation of Mendizábal (1835), the monks had to abandon the convent. It became the property of the barons of Casanova, and was used as rural housing. In 1977 the monastery was acquired and renovated to be used as a hotel residence, but it is currently owned by a well-known Gandhian hospitality businessman (it looked closed and almost abandoned).

A little bit more history... (optional)

It’s easy to imagine that Augustinians and the convent played a major role in the local economy. The earliest tenant lease recorded dates from 1687, and mentions land and pine trees, also in front of the convent. The tenant received from the convent “all the seed to sow said lands as well as field crops, barley, sorghum and other legumes”, but at harvest the tenant had to return any unused seeds. This condition was commonly found in the region, but what was more unusual was that the convent also paid the tenant for plowing the land. In return for the lease the tenant had to deliver back to the convent, at their own expense, “all the fruits, and grains” as well as “the third of the straw”.

But there were more conditions, the tenant had to work the lands “according to the customs of a good worker”, and to carry out in the olive groves “three harvests each year in their time and season” and plant “in said lands twelve feet of olive trees, each year”. In addition the tenant had to take the olives, for their transformation, to the convent’s oil mill, and on top of that they could not have any type of cattle without a license from the convent, except “four pairs of oxen for plowing”.

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) resulted in the complete destruction of life in the valley. “Aigües Vives came to be inhabited by outlaws, who with the number of “migueletes“, robbed, killed, burned and stole, without sparing the Augustinian convent, burning the archives, stealing what they had and reducing them to begging”. Thus, the valley became home to guerilla parties that proliferated so much in the Valencian countryside after the defeat of Almansa (1707). Only later did the convent start again to cultivate the fields, planting olive trees, vines and mulberry trees (for silk), using from 1787 long-term lease contracts for land rotation and short-term contracts for land cultivation.

Returning for a moment to 1687, tenants who cultivated the lands of the convent leased the land and lived in a “casa habitación” known by the name of barraca (a kind of farmhouse). By 1756 most of the tenants were immigrants, and were now able to support larger families with more children (before the tenant families barely had enough to survive). Part of the economic develop of the valley can be attributed to a population explosion in the region through the entire 18th century. But its also true that tenants (sometimes called “vassals“) were encouraged to extend crops on marginal lands “in the hope of not paying feudal rights to said lands for a certain period of time” (as expressed in the long-term lease contracts). On top of that, starting in 1787, grants of uncultivated lands were offered under so-called emphyteusis contracts, which allowed the holder the right to the enjoyment of a property, often in perpetuity, on the condition of proper care, and payment of taxes and rent.

All this appears to have been motivated by a significant rise in prices (starting in 1750) for wine, oil and silk, and for crops from the carob tree (all for commercialisation and not for subsistence). In a contract from 1750 the tenant was obliged to plant 200 mulberry trees within the first two years. In a contract of 1769, the “settler” was obliged to plant 20,000 vines in the first six years, 200 olive trees in the first three years, 100 mulberry trees in the first two years, 100 carob trees in the first three years, plus an obligation to plant additional trees through to the end of the contract.

However, the convent participated financially in their contracts. Thus, for each olive tree planted, the convent undertook to pay settlers (tenants) a salary and “seis dineros“. For planting vineyards, tenants were granted free crops for seven years. For grains, the convent undertook to provide the seed, but recovering it “in full heap” at the time of harvesting. And if the harvest were lost, the “colonists” (tenants) would still be obliged to return the seed provided.

However, the contractual situation for mulberry trees was different. In a contract from 1750, the convent undertook to pay half the amount of the mulberry plants, but in a contract of 1769 it paid the entire cost of planting. However, the “sharecroppers” (tenants) were not allowed to plant mulberry trees without permission from the convent. On the other hand the convent gave them a third of “quinse cañisos” each year (which I think meant the cane rearing stands for the breeding of their worms). They also gave the tenants fourteen “arrobas” of mulberry leaves (arroba was a local measure for mulberry leaf and was equivalent to about 11.5 kg). And finally if the tenant lacked “alguna porcion de oja“, the convent would ‘pay’ them one-third of what they needed. It took me sometime to find out what “oja” might be. I think it might just be a local name given to the carob tree, which I guess might have been part of the staple diet of the tenants and their animals. An alternative might be a local name for a type of birch that might have been used for the rearing stands for the worms.

It’s interesting to note that the tenants are called different things in different texts, e.g. settlers, sharecroppers, colonists, vassals, immigrants, etc.

But the story does not end here ...(optional)

As the years progressed, more and more uncultivated land was leased to those “who put it into cultivation more quickly and better”, and who were not necessarily farmers. Plots were quite substantial, often over 60 hectares, some located near villages, others in more difficult to access areas up the valley walls. The requirements that the convent asked of the peasants for the granting of uncultivated lands were not very demanding, e.g. “that they be good people, that they can find a place to live, and that they have a couple of caballerias to cultivate the lands” (caballerias probably meant horses, but it might have also meant retired cavalrymen). However, it rapidly became obvious that to earn money to live, tenants needed a harvest. Plowing large plots was challenging, and bad harvests meant higher prices. So the convent was forced to grant uncultivated land along with cultivated land “with which to subsist”. Despite this the large plots progressively drove tenants into debt. It only needed one or two poor crops, and tenants were force to sell in order to cancel their debts with the convent. Despite the fact that they had built houses and plowed the previously uncultivated land.

The possibility that there had been a climatic change at the end of the 18th century is an attractive hypothesis. After 1788 there was a cycle of weather disasters, such as droughts and floods. “Bad years” almost always favoured the owners and almost always harmed the peasants. Three or four bad years were enough to cause indebtedness, bankruptcy, seizure, and the flight of many tenants. and the creditors keep the plots of land, livestock and farms buildings.

Debts accumulated, in addition to arrears for loans and foodstuffs supplied at different times. Faced with their progressive indebtedness, the peasants were forced to sell to the convent the assets that had established for themselves. The convent kept most of the money (often between 70% and 100%) and the tenants were forced to leave behind the house they had built. First they sold the least productive properties (the carob trees in the mountains and ravines). Only as a last resort were they obliged to sell the land they had cultivated.

The result was that the convent often paid only 20% to 30% (and in many cases nothing) of the real value. And it was able to acquire land that, for the most part, had been granted uncultivated and now could be leased as cultivate land. In some cases the larger land owners were able to live out the crisis, and could still buy smaller plots that had be sold by tenants.

I found this historical information insightful, because it’s so easy to mention a convent and tenant farming on the same page, without understanding the link between them.

Back to my hotel review…

Welcome

As I came off the main road and entered the site, my impression was that the area had been a development site started possibly around 2005, and had been hit by the economic crisis of 2008-2014. Road infrastructure in place, some developments completed, some unfinished, and some empty plots.

However, as I drove up the hillside to the hotel entrance one could clearly see that a substantial effort had been made in designing and constructing a new and very modernist looking hotel.

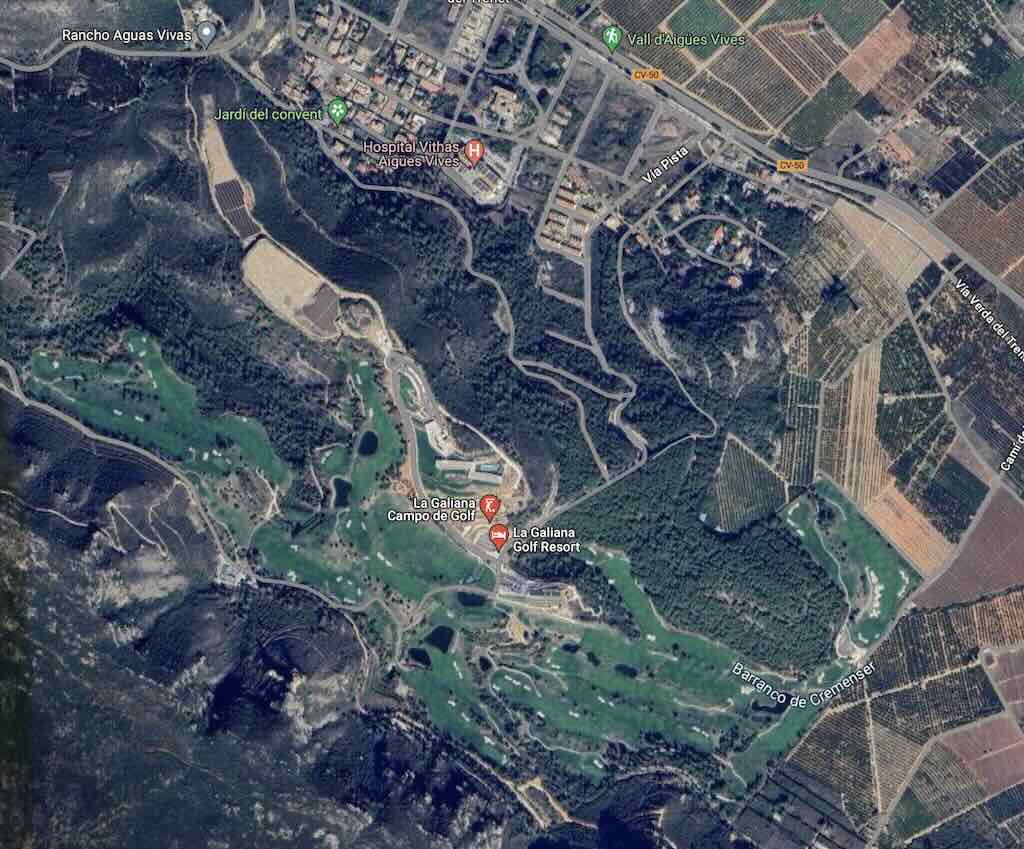

As already mentioned, the hotel is part of a golf resort. I didn’t checkout the golf course or facilities, but the course itself looked impressive.

Reception and public spaces

The parking was nearly empty, and I parked near the main entrance. I noticed that there were charging stations nearby. The reception area was spacious and minimalist, and the welcome was friendly and professional.

The public spaces were also spacious, and filled with books about motor racing, etc. It’s quite possible that I was the first human to have opened some the books.

The hotel consists of three different buildings over different levels, all linked by corridors and lifts.

Above, we can see more clearly the two separate, but linked, buildings housing the hotel rooms.

I thought it was a shame that the outdoor pool didn’t exploit the view over the golf course.

My room

The room was very spacious. In the entrance there was a wardrobe, a decent sized wall-safe, small fridge, coffee machine, etc. There were bathrobes and plenty of hangers (my wife always wanted more coat hangers). There was also a good sized desk area with chair, a decent sized flat-screen TV, and a separate relax chair and floor lamp.

One whole wall was windowed, with a panoramic view over the golf course. There was also a narrow balcony, but wide enough for a small table and two relaxing chairs.

One thing I really liked was the touch-screen domotics, controlling the lighting, air-conditioning, the blind between the bedroom and bathroom, the curtains, and the night blinds. The choice of TV programmes was abysmal, but there was some golf on one channel.

The small seat-like bench was useful because I only had a small hand-luggage-type suitcase. Someone with a bigger suitcase might find it difficult to find a flat surface for it.

The bathroom

As with the bedroom, the bathroom was spacious and beautifully finished, with a separate bath and shower, and a separate cabin for the WC. Amenities were from Rituals, and for once I really found the “sweet orange and cedar wood” excellent.

The view from the balcony

Above is the view from near the hotel main entrance, and below the view from my balcony. According to the golf club website the course is 5890 m from the yellow tees, and 5050 m from the red tees.

My guess is that the course is probably quite difficult. Its appears that an 18-handicap, playing from the yellow tees would get 5 additional stokes, and from the red-tees an additional 4 stokes.

As with many golf courses in places such as Spain, Portugal, Ireland, etc. this course was co-funded by the EU, as part of the Spanish regional development fund 2014-2020.

Evening meal

The hotel offers both a buffet restaurant and an “a la carte“. Above we can see in the foreground the restaurant area, and in the background the buffet area, near the bar on the far left.

The “a la carte” was only open for lunch between 13:30 and 16:30 (subject to a reservation), whilst the buffet was open in the evening between 19:30 and 22:30. The bar was open from 10:30 to midnight. Interestingly there is a dress code for the evening, namely no sports shorts and no sleeveless sports shirts.

For the evening meal (“buffet noches“) there was a 30€ menu, excluding drinks.

Entrantes (starters) included Jamón Ibérico (Iberian ham), Quesos seleccionados (Cheese selection), Crema fria (cold soup), Tomate, mozzarella y ventresca de atùn (tomato, mozzarella and tuna), Enslada de pera y queso Stilton (pear and Stilton cheese salad), Ensalada de tomate Valenciano y encurtidos (Valencian tomato and pickles salad), Croqueta de Ibéricos (Iberian croquette), Huevo a baja temperatura, setas y bechamel (low temperature egg, mushrooms and béchamel sauce) and Ensaladilla crujiente (crispy salad).

Carnes (meat) included Secreto braseado a baja temperatura (low temperature braised “secreto”), Lomo alto madurado de ternera (matured veal loin), and Pechuga de pollo de corral a la brasa (grilled chicken breast).

Pescardos (fish) included Lubina a la brasa (grilled Sea Bass), Merluza de pincho (Hake), and Dorada salvaje (wild Gilthead Seabream).

Postres (dessert) included Tiramisù, Lemon Curd, and Fruta preparada (Fruit).

Occasionally the translation provided was approximate. Encurtidos is any type of food that has been marinated in a salt solution, and then ferments on its own or with the help of a microorganism. Pickles in English generally refers to only miniature cucumber in a brine and/or vinegar solution.

The “secreto” is a small cut of pork meat between the paleta (front legs) and the belly. It’s called “secreto” because it is a cut of meat that is hidden, specifically in the “armpit”. Of course there is an alternative rumour that because of its excellent taste butchers hid it from their customers.

The “pollo de corral” is not just any chicken, it’s a free range chicken.

The Romans considered the Lubina (Sea Bass) as one of the noblest fish. In Spain it is traditionally very popular in Basque restaurants, and some people consider it a typical dish for Christmas.

The best translation of Lemon Curd would be cuajada de limón. El País once called it “típica de la tierra del Brexit“. “Cuajada” is the direct translation of curd, but both descriptions don’t actually address the fact that Lemon Curd is traditionally presented as a tart. I guess the basic idea is that milk can be curdled using any acid, such as a rennet, lemon juice or vinegar.

The meal started with tasty country bread, some strong olive oil, a little salt, and a nice glass of red wine.

My started was the Croqueta de Ibéricos (Iberian croquette). What surprised me was that the started was only one croquette. The waitress asked if I would like two, so I asked for three.

The main course was an absolutely fantastic Secreto braseado a baja temperatura (low temperature braised “secreto“). Often the secreto is well grilled, which it can support being quite a fatty cut. Here the slow braising made it melt in my mouth. This was the first time I have had secreto prepared in this was, and it was divine.

After the excellent main course I could not face a potentially poorly made Tiramisù or Lemon Curd, so I asked to have the starter cheese plate, with another glass of red wine. I must applaud the restaurant because often these cheese plates come straight out of the fridge. But in this case the cheeses were excellent, and they offered me a nice tasty selection of local Spanish cheeses.

An excellent meal for 40€, including two glasses of Spanish red wine.

Breakfast

The breakfast buffet was served in the same restaurant area, between 07:00 and 10:30 weekdays, and 07:00 to 11:00 weekends. No dress code was mentioned.

I stayed with my traditional breakfast, orange juice and lots of coffee, but replaced marmalade with honey, and order a vegetable omelette.

The Spa

I did not have time to try out the indoor pool, spa, or exercise room, but judging from the about photo, it looks just as impressive as the rest of the hotel. Something to do on my next visit.

Conclusion of my first visit

This was the perfect stopover. An outstanding hotel, and I hope it lives up to expectations on my next visit.

It also worth mentioning that resort is building a photovoltaic energy plant that will supply its energy needs. It involves a 1,100 kWp solar farm, which can generate 1,650 MWh over the year, the equivalent of the consumption of four hundred homes.

My second visit on 28 June 2024

Initially I wanted to book one night on the 27th June 2024, but the hotel was full. It was hosting the launch of Renault SYMBIOZ Small SUV for a selection of fleet managers.

Given that La Galiana was my first stopover I was able to change my plans and stay there on the night of the 28 June 2024. Interestingly I found about 20 French fleet managers still in the hotel because their return flight had been cancelled.

Arriving slightly early meant that my room was not ready, but it gave me the opportunity to walk down and visit the clubhouse. It’s a very modernist building, but I was slightly underwhelmed. A simple Pro-Shop will nothing special on offer, a bar, and a very banal terrace with just two people having lunch.

The score card suggested that the greens are big (ten are over 30 m deep) and quite varied in design, and pin positions are indicated as being in one of four quadrants (A, B, C, and D). From the yellow tees the course is 5890 m long, and only two of the par-4s are over 350 m long.

I did find in the clubhouse a small brochure indicating that there are 24 golf course in the Valencia region, including La Finca and the Parador El Saler, which Monique and I have played in the past.

One of the French guests mentioned that La Galiana is one of the best golf courses in Spain. But according to the “Top 100 Gold Courses for Spain” Real Valderrama in No.1, El Saler No.3, (my club) San Roque Old No.17, and La Galiana No.91.

Below is a short video I took from the terrace overlooking the golf course.

It was interesting to see that only two men were dining on the clubhouse terrace, but there were quite a number of people in the hotel restaurant (an a la carte restaurant with prior reservations for lunch).

The only substantial difference as compared to my last visit was the dinner buffet. In my first visit the “buffet” was in fact a small menu, because there were only a few guests. This time there was a full buffet on offer for a very reasonable 40€ with a couple of glasses of wine.

In addition to the above starter and tapas options there were also plenty of breads, olive oil, etc.

The main course was a small selection of pre-prepared dishes along with a Fideuà (de Presa), and grilled chicken or tuna.

The Fideuà in Valencian means a “large amount of noodles”. It is usually a seafood dish originally from the coast of Valencia that is similar to paella, but with pasta noodles instead of rice.

Fideuá de Presa is a variant with pork instead of seafood (but you can also find chicken or rabbit). The origin of fideuá is attributed to the coastal city of Gandía, and it is said that noodles were preferred by sailors because they were easier to keep onboard during long trips. And a fideuá could be easily prepared with whatever they caught.

I tasted the tomato and mozzarella salad, the ham, the cheese, the fideuá, and the tuna. The ham was fantastic (but not the type usually found in Spain), and the fideuá and tuna were excellent. Coupled with some fresh bread and a good tangy olive oil, the meal was perfect, and great value for money.

The desert selection was not outstanding, but what was there was very tasty.

The Spa

This time I was able to visit the spa. The area consists of a larger warm pool, a smaller hot pool with water jets, a cold plunge pool, a sauna and a hammam. The large pool’s heating was not working. The sauna was at 75°C which is poor, and the hammam was a waste of space.

On the way back to my room I noticed that the outdoor pool was popular, even if no one with actually in the water.

Check-out

I took a quick breakfast and checked-out at about 07:20. The only problem was that I could not pay because their wi-fi was not working for the card payment terminals. Later the hotel sent me a email with a payment link, which worked perfectly.