I was in Turin Airport picking up a friend, and we decided to visit Lingotto, before driving up through Val d’Aosta.

We have to first understand that there are two sides to the “Lingotto”, which actually translate to “Ingot” in English. The first side is the history of the original building, and the second side is what it has become today.

We can “jump-start” our visit with the video “The Last Surviving Factory Rooftop Racetrack“. Or if you prefer an English commentary with an Italian accent, check out “A Test Track In The Sky: The Story Of Fiat’s Lingotto Factory“.

A little history

After several trips to the USA and much debate, in 1915 FIAT decided to build a new ‘American’-style plant in the Lingotto area in Turin, and construction began in July 1916. The design and the direction of the works were entrusted to the FIAT’s in-house engineer Giacomo Matté-Trucco.

The building was intended as a direct physical manifestation of its manufacturing concept. So a continuous production line received raw materials on the ground level and conveyed the gradually assembling chassis from floor to floor, with the completed vehicle undergoing a final test lap of the roof top circuit.

This concept was at odds with the typical multi-storey factories of Ford, whose automobile ‘gravity-flow’ production lines descended through the floors, until the completed models drove directly out onto the forecourt.

We should not forget that the Lingotto factory measured 507.3 metres in length and 80.5 metres wide, and consisted of two parallel five storey structures 27 metres high. The total area was around 250,000 square metres.

Work on the test track, perhaps the most famous symbol of the factory, was completed in 1921. The factory was ceremoniously opened on the 22nd May 1923 by the king of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele III.

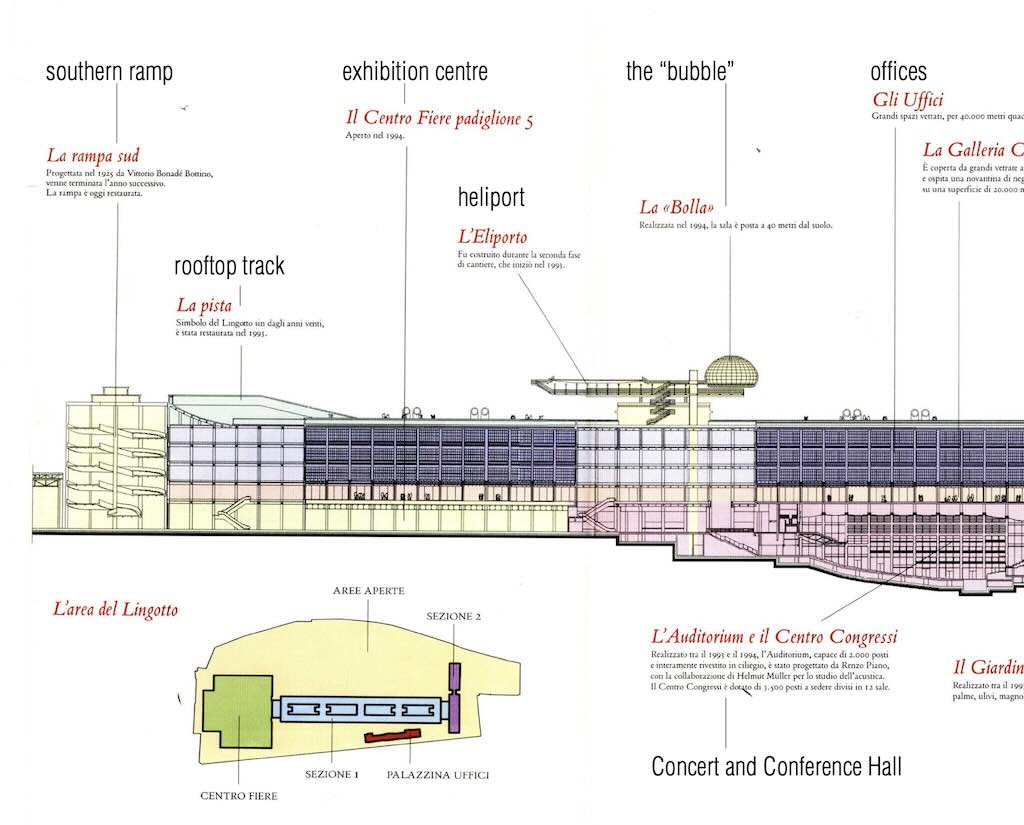

The North and South Ramps, the other two symbols of the Lingotto, were completed in 1925 and 1926, when the office building, home to the company’s Board of Directors, was also inaugurated.

Although parts of the building had actually been in use since 1917 to assemble airplane motors during WWI (Italy entered the war on the side of the Allied Powers).

At that time, Turin was going through its first industrial revolution. Having started out with largely textile industries in the northern part of the city, it developed mostly mechanical production to the south, beginning with Borgo San Paolo, where Lancia was also based, continuing with the Lingotto area, and a few years later, reaching Mirafiori. The FIAT production plant in Mirafiori, designed from 1933 onwards, was inaugurated on 1 May 1939 and doubled in size in 1956 (from 2016 this is also where Maserati are based).

Even before it was finished, the Lingotto building had become part of the popular Italian imagination created through the images of famous photographers, as well as the many visits to the factory by almost every major delegation visiting Italy. A place of work, it also almost immediately became the symbol of an industrial Italy that was trying its best to take off.

The poet and founder of Italian Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, famously described the Lingotto as “the first invention of Futurist construction” in his Aerial Architecture manifesto of 1934, shortly after a visit to the plant.

Le Corbusier was the most notable commentator in praise of Lingotto. In the second edition of his widely published “Vers Une Architecture”, he used a series of photographs of the factory to accompany the final essay “Architecture or Revolution”, where he questioned why advances in mechanised and efficient industrial processes of the era had not been applied to the architecture of the home.

The Italian journalist and art critic Edoardo Persico had a more personal reading of the Lingotto factory, having been employed on the assembly line in 1927. In his essay “Fiat: Le Operai” (Fiat: the Workers), first published in L’Esprit Nouveau Magazine, Persico begins in praise of the Lingotto factory, comparing the rationality and culmination of its design with the holy order and grandeur of a cathedral, and drawing a comparison between the roof top test track and the crown of a king. But gradually the metaphor took on a more negative complexion, as the factory’s architect came to be accused of formulating a design that embedded a dictatorial hierarchy and rigid system of laws over the workers, and he wrote “Only the track is free beneath the heavens and before God”.

A more technology-oriented analysis of Lingotto, starts with the work of Frank Bunker Gilbreth, and later his wife Lillian Moller Gilbreth, that would lead to the analysis and implementation of motion studies in the industrial workplace (early time and motion studies).

Gilbreth’s work into “motion-studies” would soon be coupled with the “time-studies” of manufacturing efficiency conducted by Frederick Winslow Talyor, which in turn would lead to substantial changes in the industrial workplace.

This work was controversial in its treatment of employees and standardisation of the working procedure, but its results and impact were undeniable, and we all remember Charlie Chaplain’s “Modern Times” (1936).

It was Henry Ford, that saw that the process of manufacturing could be made more efficient and further quantifiable with a more automated and mechanised approach, relying on further advancements in machine technology but also the realisation of a continuous assembly line, unforeseen by Taylor at the time.

The assembly process and its arrangement throughout the Lingotto’s departments demonstrate a number of principles of both Taylor and Ford. The factory followed the logic of breaking down the automobile into its smallest constitute parts, creating specialised departments with carefully structured hierarchies, and employing staff trained for that specialism. These departments, down to their machinery and workforce, were treated like components themselves, positioned precisely at fixed locations and arranged consecutively throughout the ascending shop-floors of the factory, ensuring only parts and materials were the moving elements within the system.

The ambition to systematise these processes and create a vertical sequential production line was undermined however by a number of problems where material or components had to bypass whole sections of the factory (pressed metals, engine parts), or elements had to travel back against the directional flow of assembly (engine testing, finished car). The continuous assembly line was described by Mussolini’s scribe during his visit in 1923 as “a long intestinal cord, grabbing, refining and digesting its continuous nourishment”.

But in reality it was a more dislocated network than had been portrayed. This was in part due to the lack of mechanised means of internal transportation or machine-led conveyance between processes, the continuous assembly line could never be fully realised due to the breakage created through its changes in level. As opposed to Ford’s gravity flow system, which took advantage of changes in level as a means to aid assembly, the Lingotto factory relied solely on its industrial lift shafts, located on each side of its five service blocks, to transport all elements of the automobile vertically through its shop floors. This break in the line of continuous production would dramatically increase the manufacturing time, and inevitably significantly reduce the number of cars produced. The demand for transport throughout the factory floors, reliant as it was on just the service lifts, caused long delays and areas of congestion around the elevator blocks, as cars and materials awaited delivery to the next stage of assembly. The delays were most evident on the roof top track, where lines of waiting cars frequently obstructed vehicles in the course of their own test laps.

So despite initial aims to produce 200 cars per day, the Lingotto factory at the beginning was achieving only 60-80. Although this was double the production of the year before, a vehicle was taking 29 hours and 14 minutes to assembly, whereas the best American manufacturer was achieving a completed vehicle in a mere 6 hours 15 minutes. At the outset, therefore, the performance of FIAT’s plant, as initially arranged and organised, was already eclipsed by its American competitors. This is why the spiral ramps were built in each end of the building.

When Fiat eventually committed to more significant investments in machinery between 1925-1926, the beneits in terms of output were immediately noticeable, but subsequently so were the limitations of the building itself. By 1930, Lingotto had reached the limit of its development potential, with the physical confines of the site simply leaving no room for further extension or modification.

Even the famous roof-top test track, the crown of Fiat’s facility, began facing its own troubles. By the late 1930’s testing was relocated because the frequency and speeds of tested cars generated vibrations which triggered structural deterioration throughout the factory. In addition the short 27° banked curves, dictated by the structural bay widths below, were unsuitable to negotiate at the speeds that FIAT’s vehicles were increasingly capable of achieving.

In April 1937, the first foundations were dug for FIAT’s new factory, on a large expansive site to the southwest of Lingotto in an area known as Mirafiori.

In May 1939, the consensus was to demolish Lingotto, but this plan had to be put on hold with the outbreak of WWII. And after the war, FIAT decided to retain the Lingotto factory, using it as a subsidiary facility to its Miraiori complex. The plant focussed on the production of smaller car models and engine parts, with areas rented out to other manufacturers, and it would continue operating in this guise until its eventual closure in 1982.

The slow death of Lingotto

The reality was that already In 1915, Henry Ford was looking beyond his Highland Park Plant to a new 2,000 acre Eagle Plant on the banks of the River Rouge in Dearborn, Michigan.

Ford had realised the inadequacies of vertically organised assembly during his years at Highland Park. The changing in levels through ramped conveyors and especially elevators, although attempted, could never meaningfully contribute to an efficient assembly process. This resulted in a waste of time, energy and ultimately profit. Ford’s new ‘Eagle Plant’ building opened in River Rouge in 1918, and was built around five large assembly aisles 15 metres wide and over 500 metres long. These vast production corridors were large enough for the construction of anti-submarine boats used in WWI. Crucially the building was focused upon a single ground storey shop-floor. This negated the need for the concrete structural system required in order to dampen vibrations through multi-storey factories. Instead it allowed a thinner steel framed construction that could provide wider spans, thus increasing flexibility and shop-floor capacity.

Ford meticulously arranged all elements of River Rouge Plant along a north-south axis. This provided clear circulation routes and parallel lines of assembly, integrating road, rail-track, and the river. It thereby avoided any junctions that could lead to congestion. The new optimum configuration removed all downtime in the transportation of materials. Ford also ensured enough space was left around each building for future expansion.

Fiat would of course follow suit in favouring a single storey horizontal organisation through the development of its Mirafiori production facility in 1939.

What to do with the old Lingotto?

So with the opening of the Mirafiori plant, the Lingotto was made to look obsolete. Its multi-storey production line seemed anti-economical. Even prior to WWII, discussions began about its possible reuse. Nevertheless, the plant remained in production, employing thousands of factory workers, until 1982. In actual fact, discussions on possible new uses began in earnest at the end of the 1970s, and intensified in the wake of the 1980 crisis. These were interesting moments of confrontation in which companies, administrations, trade unions, intellectuals and technicians all took part. However, almost nobody questioned the need to preserve the plant building.

Still at the beginning of 1970s, nearly 80% of industrial workers in Turin were involved in car manufacturing. But the introduction of automation technologies contributed to cutting 38,000 workers between 1980 and 1982. In 2002, the crisis of car manufacturing was blatant as FIAT announced the closure of 18 production plants all over the world.

A key event in shaping Turin’s new economic basis was hosting the 2006 Winter Olympics. When the Games were awarded in 1998, Turin’s policy-makers launched an intensive branding campaign to change the city’s industrial image into a vibrant, cosmopolitan and cultural city.

While the 2006 Winter Olympics supported a general idea of Turin’s global importance, the 2009 agreement between FIAT and Chrysler further emphasised the international visibility of the city. But FIAT is obviously no longer a “local” company and Turin is no longer a one-company town. Ultimately, in 2014, the headquarter of the FIAT-Chrysler group was moved to London and Amsterdam.

So what to do with Lingotto? It was the FIAT company that took the initiative. Above all, Giovanni Agnelli and Cesare Romiti wanted to keep the building in use while opening it up to new opportunities.

Twenty architects, chosen from among the most famous in the world, were invited to present their projects on the possible new lease of life for the Lingotto building. The projects were presented in an exhibition organised in 1984 and discussed at various conferences and meetings. The following years were full of proposals, culminating in Turin City Council’s official commission in March 1985 awarded to Giuseppe de Rita, Roberto Guiducci and Renzo Piano to draw up a feasibility plan for its reuse. The ensuing plan was finally approved in November 1987. The city and the region approved the new executive plan, which foresaw changes to the allocation of purpose, in 1990.

Around that time, Turin experienced a deep economic crisis resulting in a wide-ranging process of industrial reorganisation. The most visible consequence was the dismissal of industrial areas and the creation of new social and urban planning options in the city. The study for the new urban regulatory plan was entrusted to the Vittorio Gregotti studio in 1986, the same year that FIAT commissioned the Piano studio to design the new Lingotto.

In the years between 1986 and 1991, when the construction work got underway, the Lingotto went through a phase of intense cultural activity. In the former press room, now the Congress Centre, concerts were held under the baton of Luciano Berio and Claudio Abbado, and plays directed by Luca Ronconi were performed. In June 1989, the exhibition on Russian and Soviet Art, 1870–1930 opened in the workshops, followed in 1992 by the exhibition on American Art, 1930–1970. The building also housed exhibitions on the architecture and urban planning of Turin as well as on Andy Warhol.

The construction site of Renzo Piano’s Lingotto began Phase 1 in 1991, with the reorganisation and completion of the metal press building, intended for use to host trade fairs and major cultural events (from the Turin Auto Show to the Turin International Book Fair). The renovation process was completed in March 1992. What had appeared to be a challenge that few believed in was beginning to take shape, and it took 11 years to create a reborn Lingotto.

Work on the shop floors, the actual production line area, began in 1993, with a project covering two thirds of the factory (Phase 2) to be completed in three years. The third and final phase, which ended in September 2002, was undertaken in November 1999.

The iconic race track is still there, even if a little different from the original. The second photo is the latest version with the integrated garden areas.

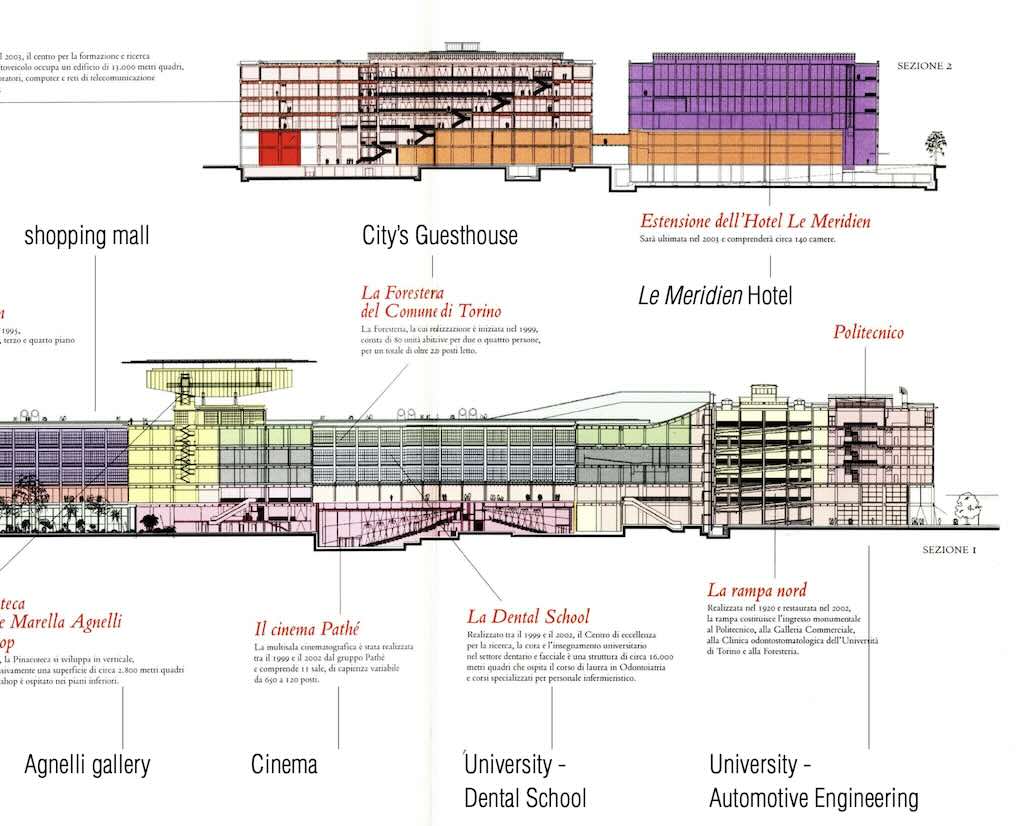

Renzo Piano’s design retained the 6×6 framework that had characterised Matté-Trucco’s design, while also managing to preserve the two façades and their reliefs linked to that framework. The new projects, the Auditorium, the Bolla (‘Bubble’), the Pinacoteca, the new Polytechnic, the Giardino delle Meraviglie (‘Garden of Wonders’) were carried out in the inner yards, carving out a new space above the building’s skyline.

The Lingotto today stands as a multi-faceted and complex structure. It integrates culture (the polytechnic, the university, and the auditorium), hospitality (the hotel and guesthouse), services (the congress centre and the exhibition area), and entertainment (the shopping centre with the cinemas).

The most prominent of Piano’s additions are on the rootop. Seen in the distance is the glass-bubble corporate meeting room and accompanying helipad, cantilevered at either end of two 42 tonne girders upon Lingotto’s southernmost service tower.

On the opposite northern tower seen above, sits the “Scrigno” or ‘treasure chest’. A giant top-lit steel structure that houses a permanent collection of paintings owned by Giovanni and Marella Agnelli. This structure forms the top floor of the art gallery, housing temporary exhibitions, library and bookshop below. It is also the main access to the rooftop.

La baigneuse blonde, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1882)

Nu couché, Amedeo Modigliani (1917-18)

References

John Cook, “Lingotto – Myths, Mechanisation and Automobiles“