Expedition to Southern Lands

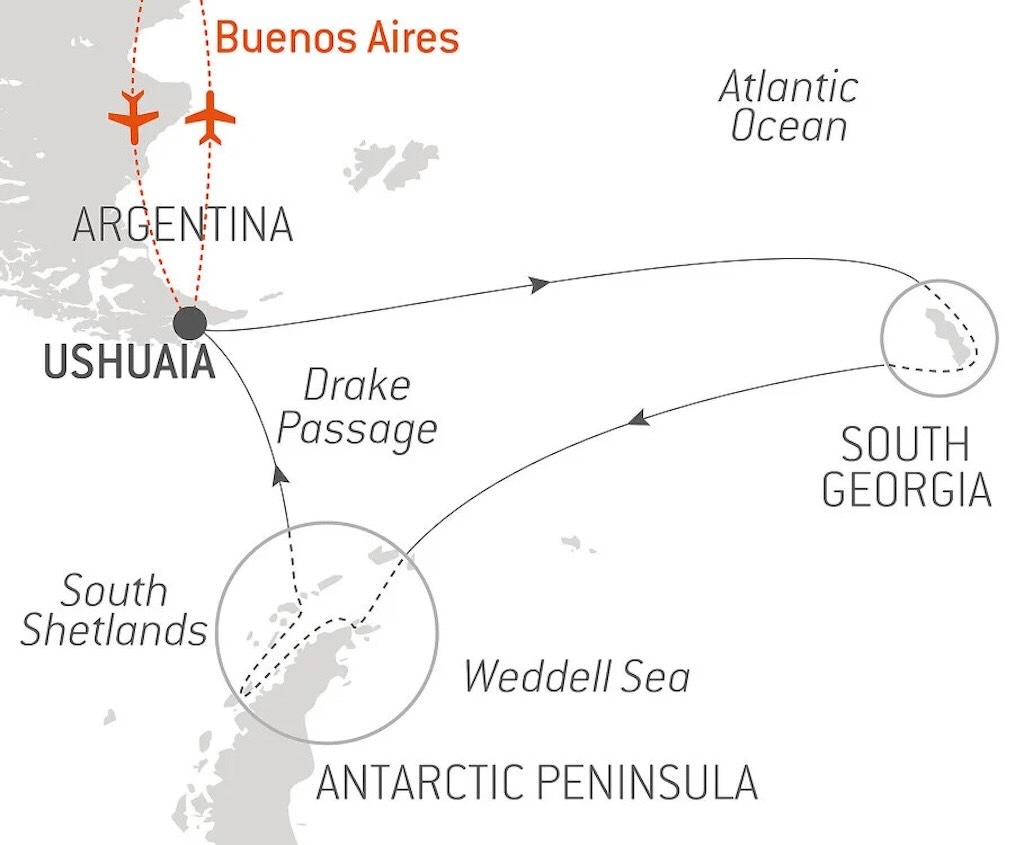

This post is a day-by-day travel itinerary of the initial part of the expedition cruise to the “Southern Lands”. It included the visit to South Georgia Island, so this means from Day 1 and my pick-up in Buenos Aires through to sailing away from South Georgia and towards the South Shetland Islands and the Antarctic Peninsula on Day 7.

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 1-7)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 8-11)

- Antarctic on Le Lyrial (Days 12-17)

In February 2025 this particular itinerary no longer appeared on the Ponant website.

This blog posting tries to touch on a number of specific questions, namely:-

- Where Is Ushuaia?

- How Has Ushuaia Evolved Over the Last 50 Years?

- How Are Waves Defined, and How Do They Affect a Ship?

- Why Is the Antarctic a Continent?

- What Is South Georgia, and Where Is It?

- What is the Scotia Sea and the Antarctic Convergence?

- How to Prepare for My First Excursion?

- How to Get In and Out of a Zodiac?

- What Do We Know About the Elephant Seal?

- What Is the Shackleton Walk?

- What’s Life Like as a King Penguin?

And the visits to Rosita Harbour, Salisbury Plain, Fortuna Bay, Grytviken, Saint Andrews and Gold Harbour.

There is a YouTube video summary of this particular trip.

The best travel summary I’ve seen is the 11-part Quest for the Antarctic Circle. The photos are superb.

I have numerous other blog pages covering other aspects of this exploration itinerary:-

- Planning a Cruise to the Antarctic

- My Antarctic Packing List

- Le Lyrial – A Luxury Expedition Cruise Ship

- Le Lyrial – Exploring Hidden Engineering

- Air Dolomiti Embraer E195

- Lufthansa Business Class Lounge, Frankfurt

- Lufthansa Boeing 747-8 – Business Class

- Ministro Pistarini International Airport, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Meliã Recoleta, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Sofitel Recoleta, Buenos Aires

- Hotel Palladio, Buenos Aires

- Lufthansa Boeing 747-8 – First Class

- Lufthansa First Class Lounge, Frankfurt

And my visit to Buenos Aires:-

I also have a separate blog post for my visit to the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

The cruise was on the expedition ship Le Lyrial.

It’s worth mentioning the difference between boat and ship. A boat is a watercraft with a wide range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size or capacity, its shape, etc. Ships are typically larger than boats, but there is no universally accepted distinction between the two. Ships generally can remain at sea for longer periods of time than boats. A ship is likely to have a full-time crew assigned. But just to confuse things, some vessels are traditionally called boats, notably submarines, riverboats, ferryboats, etc.

25 November 2024 - Starting in Buenos Aires

This was the pre-cruise day. Passengers were booked into hotels in Buenos Aires, and my booking included an overnight in the Sofitel Recoleta.

I had arrived in Buenos Aires a few days earlier, and had purely by chance booked a hotel in the same road as the Sofitel. So I took a short uber ride, around all the one-way streets, to the Sofitel, costing around $3, and arrived late morning.

The welcome process was quite simple, and well organised. It involved checking-in to the cruise, and understanding the agenda for the rest of the day and for the flight the next morning to Ushuaia.

In addition to collecting the room key, I was given a tag for my suitcase, including my name and future cabin number. I had to leave the suitcase outside my room before 22:00.

That evening there was a buffet dinner included, which I must admit was less than impressive.

26 November 2024 - Welcome aboard (Day 1)

Still in Buenos Aires, there was a wake-up call at 04:00, and a breakfast buffet was served from 04:30.

My coach left at 05:30 and was the first of five that took everyone to the airport. I did not see my luggage again until we arrived in Ushuaia.

In the early morning the 32 km trip to the airport took about 40 minutes, and during the trip we were all issued boarding passes. Airport security was relatively simple (boarding pass and passport check, and hand luggage scan), and then we all had to wait until our flight at 08:50.

As far as I know there were eight scheduled flights per day from Buenos Aires to Ushuaia, seven with Aerolineas Argentinas, and one with the ultra low-cost Flybondi. There are scheduled flights at 08:30 and 09:50, so my guess is that our flight at 08:50 was a charter with Aerolineas Argentinas.

The aircraft itself was a B737-800 of which Aerolineas Argentinas owns 31.

It was a 3½ hour flight, the breakfast was not bad (I’ve had worse, often), and my choice of music was Billie Eilish, Dua Lipa, Doja Cat, London Grammar, Stromae, Miley Cyrus, Charli XCX, etc., and no Taylor Swift (thank God). I also listened to a couple of podcasts about penguins. In any case the breakfast was a lot better than the inedible thing (possible dead chicken) we had on the return flight.

I can truly recommend SONY Noise Cancelling WH-1000XM4.

Disclaimer: I’m not paid for this plug, but they almost made me forget I was flying in a ticking time-bomb (a Boeing).

Landing was fine, but we had to wait a while to collect our luggage from the arrival area. Leaving the luggage collection area, the tag was checked, and the next time I saw my suitcase was in my cabin.

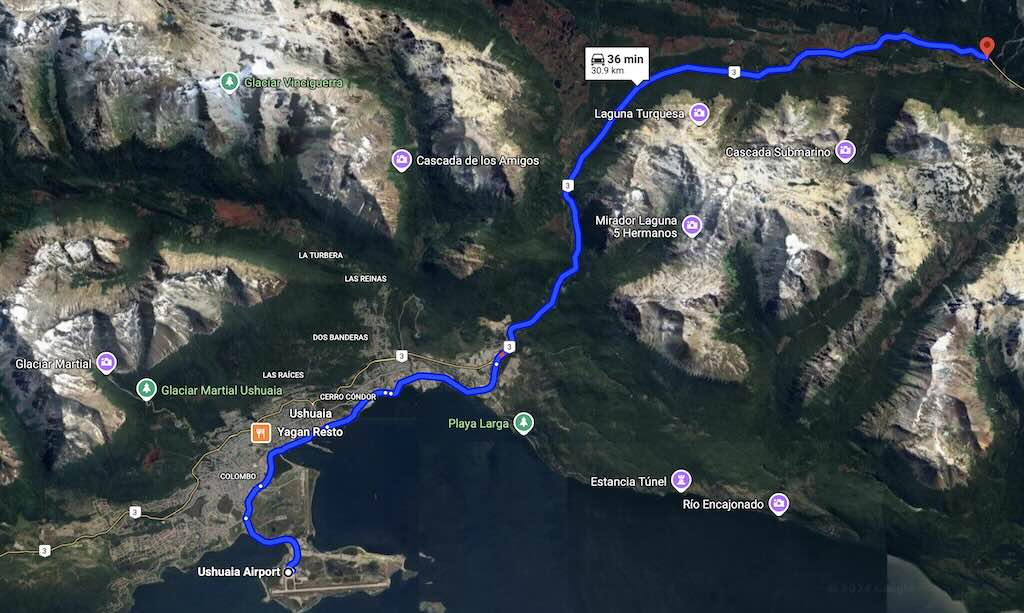

Coaches from the airport were labelled French or English, and they took everyone on a trip through Ushuaia to have lunch at Las Cotorra, address RN3 km 3025, V9410 Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina.

Before I continue with our day in Ushuaia, I would like to make a comment about the luggage. We received very clear instructions, even a kind of warning, concerning check-in and carry-on luggage. The warning was very clear, maximum 23 kg for one piece check-in and maximum 5 kg for one piece carry-on. It was clearly stated that excess luggage charges might be applied, etc., etc. Firstly, the check-in luggage left my hands at 22:00 in Buenos Aires and reappeared in my cabin on the ship. My luggage was around 20 kg, but I’m sure that some peoples’ luggage exceeded the 23 kg limit, and nothing happened. I do know that some people “declared” an addition suitcase and pre-paid excess luggage fees. In addition, whilst I respected the 5 kg carry-on limit, many people appeared to have ignored it. On the flight the overhead lockers were full with carry-on suitcases, bags, backpacks, etc., and people had trouble finding space.

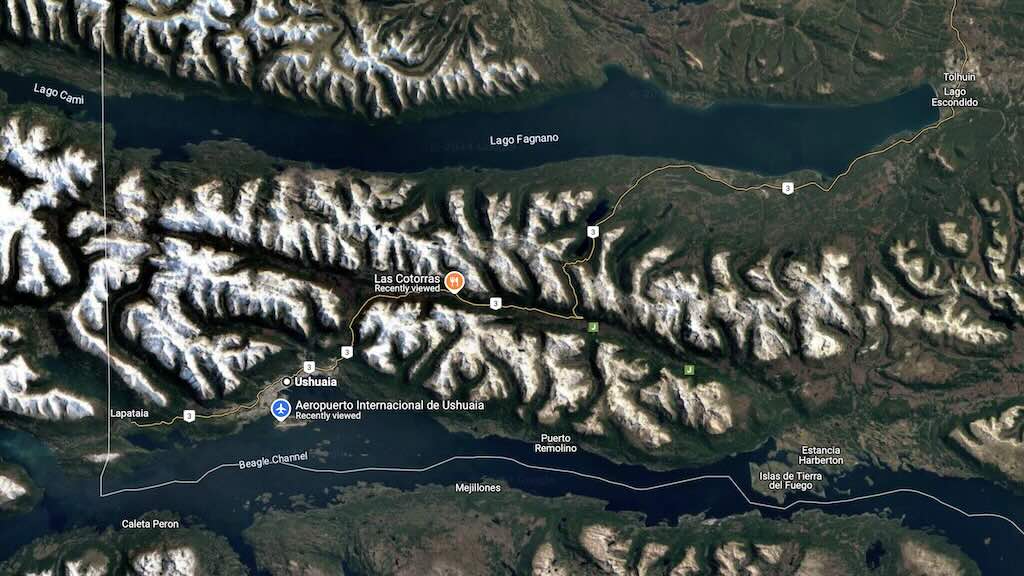

Where is Ushuaia?

Often Ushuaia is mentioned as a town, but it is in fact the capital and the largest city in the Argentine province of Tierra del Fuego.

In the above map we can see Ushuaia and the Ushuaia–Malvinas International Airport. We can also see the Beagle Channel, a strait in the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago.

The channel was named after the ship HMS Beagle during its first hydrographic survey of the coasts of the southern part of South America which lasted from 1826 to 1830.

What is interesting is the frontier (white line) between Argentina and Chile, a peaceful frontier that was the result of numerous past conflicts between the two countries.

The Beagle Channel, the Straits of Magellan to the north, and the open-ocean Drake Passage to the south are the three navigable passages around South America between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

How Has Ushuaia Evolved Over the Last 50 Years?

Over the last 50 years Ushuaia has evolved, due in part to its role in the ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom (the 1982 Malvinas War), and in part due to the important increase in Antarctic tourism.

The term Islas Malvinas (Falkland Islands) derived from the French “Îles Malouines”, a name given by French explorers in the mid‑18th century who hailed from the port of Saint‑Malo in Brittany. Over time, as Spanish influence grew in the region, the name was Hispanicised to “Malvinas,” and it has since become a powerful symbol of Argentina’s longstanding claim over the islands.

Ushuaia is around 2,400 kilometres from Buenos Aires, and typically today a commercial flight takes around 3½ hours. However, when driving, the distance is over 3,000 kilometres. Today’s drive along the well-maintained National Route 3 would take about 37 hours of pure driving time (roughly 3–4 days when rest and stops are factored in).

Fifty years ago, much of the route (especially in the rugged Patagonian stretches) was unpaved and far more challenging. There is the crossing from Argentina into Chile, and then back into Argentina, and still today, you have to take the ferry across the Strait of Magellan. With lower average speeds and less continuous infrastructure, the same journey would likely have taken around 60–70 hours of driving time, meaning a trip of roughly 5–6 days in a real-world setting.

In the early‐to‐mid‑1970s it is estimated that the city had roughly 5,000 residents, with perhaps another 7,000 people living in the region around the city. A guesstimate for Tierra del Fuego for 1970, is about 20,000 to 30,000 inhabitants.

So Ushuaia was small and remote, but it was an important outpost and gateway to the Antarctic and southern Atlantic regions. As the southernmost city in Argentina (and in the world), it served as a physical reminder and assertion of Argentine presence in the far south, a critical part of Argentina’s claim over territories like the Islas Malvinas (Falkland Islands).

Before the outbreak of the Falklands War, Argentina maintained a modest but significant joint military outpost in Ushuaia. This facility was primarily a combined Naval and Army base whose key roles were to assert sovereignty in a region close to its disputed territories and to provide logistic and maritime support. Historical records indicate that although the pre-war garrison was limited in size (roughly 100 personnel), its location made it one of Argentina’s most important southern outposts.

Although not a full airbase, there were basic facilities used for communications and occasional air reconnaissance, but it did not host permanent fighter or transport squadrons. However, the original airstrip did also serve some small regional flights. The base coordinated the transit of supplies and personnel that kept Argentina’s network of Antarctic bases operational. So the base also hosted more than one hundred civilian logistics staff who managed cargo handling, air traffic control, maritime safety, and communications.

Ushuaia’s port began as a small, multipurpose harbour supporting local fishing, basic cargo imports (including fuel and food for a sparse population), and small passenger vessels.

During the 1982 Malvinas War, Ushuaia functioned as a logistical hub. It was used to mobilise, equip, and support Argentine forces heading toward the contested islands. In addition, the city’s symbolic value was heightened. It became a rallying point for national pride, with public displays and media coverage emphasising the Argentine claim. This buildup increased the base’s strength from its pre-war level of about 100 to an estimated 300–400 personnel.

During the conflict, temporary military maintenance and logistic facilities were installed at the airport.

There are no records or reports that the city itself was directly attacked during the Falklands War. However, Ushuaia’s naval facilities were active during the conflict, for example, the ARA General Belgrano sailed from Ushuaia before being sunk.

After the conflict, Ushuaia has continued to serve as a centre of remembrance and political expression. Monuments, murals, and public events in the city commemorate the struggle over the Malvinas and keep the debate alive in the national consciousness. At the same time, Ushuaia’s role as a key logistical and tourist gateway to Antarctica reinforces its enduring importance in the region.

These layers of historical, logistical, and symbolic significance mean that in Ushuaia the Malvinas is not only seen in words and monuments but is woven into the local identity and the broader narrative of Argentine sovereignty over its southern territories.

After the cessation of hostilities, the wartime military buildup was scaled back as part of normal post-war restructuring. Before 1982 the term “Malvinas” was certainly used in official language and national discourse to refer to the Falkland Islands, but its presence in the everyday urban landscape of Ushuaia was relatively muted. For example, while government publications and media in Argentina consistently referred to the islands as “Malvinas,” local public spaces and infrastructure in Ushuaia, such as road names and even the airport, had not been widely rebranded with that term.

However, as the 1982 Falklands War (Guerra de las Malvinas) unfolded, a surge of nationalistic sentiment led to a series of deliberate changes in public nomenclature to reinforce Argentina’s claim over the islands. Shortly after the conflict, the main airport in Ushuaia was renamed to Aeropuerto Internacional Malvinas Argentinas. This change, implemented in the mid‑1980s, was intended to serve as a permanent reminder of the dispute and to emphasise the country’s sovereignty claim. The renaming was accompanied by improvements and expansions that further linked the facility’s identity to Argentina’s strategic interests in the southern region.

In the years following the conflict, several streets, avenues, and plazas in Ushuaia were renamed or newly dedicated with names referencing “Malvinas Argentinas”. These changes were part of a broader national campaign to memorialise the conflict, support public sentiment, and ensure that the legacy of the struggle for the islands remained visible in daily life. Beyond just renaming, the post-war period saw a marked increase in the presence of monuments, commemorative plaques, and public art projects in Ushuaia that highlight the “Malvinas” theme.

After the war, the large wartime reinforcement was scaled back as Argentina returned to peacetime operations (today around 150–200 personnel).

A recent census shows Ushuaia’s city population is now approximately 80,000 inhabitants, and Ushuaia’s role as Argentina’s principal gateway to Antarctica has been reinforced.

Ushuaia’s port is the departure point for Argentina’s icebreaker and research vessels, such as the ARA Almirante Irízar, that transport supplies, equipment, and personnel to Antarctic research stations (e.g. Marambio, Esperanza, and Carlini Bases).

In the decades after the war, the port underwent a series of modernisation programmes. Investment figures for the port’s upgrade have exceeded $50 million over the past 20 years. Today, the port now accommodates over 100 cruise ship calls per year, with annual tourist passenger figures estimated at around 200,000. Remembering that in the off-season (May-September) there are almost no cruises due to the harsh Antarctic winter. In addition, the port remains a major hub for importing goods and for the export of seafood (notably lobster and other cold‑water seafood).

Ushuaia’s international airport is used for both military and civilian flights that carry personnel and critical cargo to Antarctic bases. These flights often include elements of the Argentine Air Force that support long‑range operations. The airport was substantially upgraded in the late 1970s (partly in anticipation of increased strategic needs) and then further modernised after 1982. Major renovation and expansion phases took place in 2008 and again in 2015. Recent investments in the airport have been in the range of $20–30 million to expand the runway, improve terminal facilities, and enhance navigation and security systems.

Today, the airport handles roughly 250,000 passengers per year. There are typically 10–15 daily flights from Buenos Aires and other Argentine cities, with about 85% of flights domestic and 15% international (including seasonal routes to Chile).

Argentine fixed‑wing aircraft regularly land at their Antarctic bases. For example, Marambio Base, one of Argentina’s key installations in Antarctica, is equipped with an all‑weather runway (about 2,450 meters long) built on compacted snow and ice. This runway is designed to accommodate aircraft like the C‑130 Hercules, enabling the regular transit of supplies, personnel, and scientific equipment.

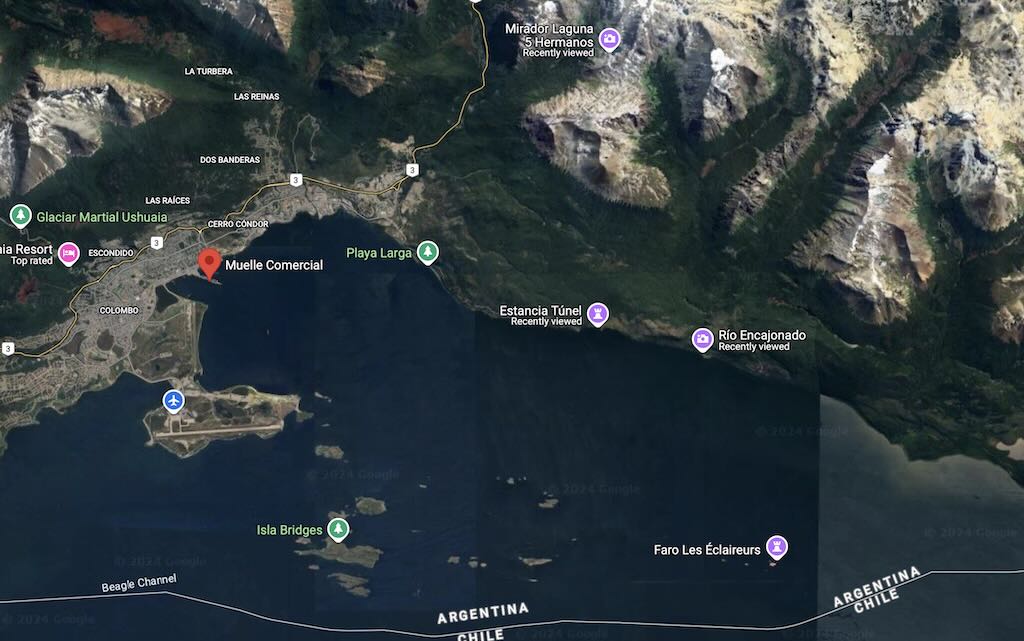

We arrive in Ushuaia

Above we can see the Muelle Comercial, the dock where Le Lyrial was moored. And below we can see the route taken for lunch.

On the coach we had a fantastic guide who explained a lot about the history of Ushuaia, and life there today.

The meal in the restaurant was barbecued lamb. Many people were very complimentary, others less so. I found it a bit dry and average. However, the atmosphere was very friendly.

The next step was to drive back to the port, and board Le Lyrial.

Returning to the port there was considerable traffic because the main street through the city, Héroes de Malvinas, was closed for some repair work.

Our ship Le Lyrial was moored along with Le Boreal (another Ponant ship), the Fridtjof Nansen (Hurtigruten), the Seabourn Pursuit, and the fantastic private megayacht Octopus (check out this YouTube review).

Above we have a short video of the dock, and below we have view from our ship of Ushuaia and the mountains in the background (ending with the famous Octopus).

Boarding was very simple. There were a number of cruise liners docked, but only ours was boarding. Once on board we were offered Champagne and a snack, and asked to “check-in”.

This involved firstly handing over our passports in exchange for our cabin access card.

- A very useful “Daily Program“, which was issued in the evening preceding each day

- Information on connecting to the onboard wifi

- A welcome from the “Travel Ambassador”

- A 5% discount on booking a future cruise

- An invitation to use the onboard “beauty area”.

The reason it’s important to turn on Airplane Mode is that in or near a port, there can be a roaming signal. However international roaming and data fees can add up to a substantial bill. In addition, some service providers also have “Maritime Services”, which can also be very expensive. This cruise ship provided free wifi access, but on many cruise ship passengers are expected to purchase a block of time/data.

Given that ships are mostly made of metal, signal attenuation is a major concern. The whole ship is festooned with access points, often hidden behind the TV is each room. These access points are tied into an onboard data centre, usually through several remote data points placed throughout the ship. In addition each cabin had an IP-based phone and TV. There was also a warning that at times there would not be TV services available (I never switched on the TV).

The “Daily Program” was vital since it set the daily agenda for each and everyone.

At 17:30 there was the welcome by Captain Michel Quioc. The family name Quioc is rather unusual but can be found in Canada, the Philippines and France, and in particular in the region of Brittany.

This welcome was followed by the mandatory life boat drill.

Everyone had to know how to don their life jacket (stored in each cabin), proceed to the muster station (the Theatre), and then proceed from there to the life boats.

We would later be given a separate life jacket to be worn when leaving the ship on the various excursions.

The day ended with dinner in one of the two onboard restaurants.

I took 50 mg dimenhydrinate just before bed. The advice was to take seasickness medication preventatively, before it might be needed.

How Waves are Defined, and How Do they Affect a Ship?

During the welcome the captain mentioned a “calm” sea with a swell/houle of between 3-4 m.

So we need first to understand better how waves in the sea are defined, and then how those waves affects a ship.

Let’s start with how we define waves as disturbances on the surface of a large body of water such as an ocean. The rising and falling of waves can be created by a variety of factors, including wind, gravity, and the displacement of water elsewhere.

- Wind waves (often just called sea waves) are created by wind blowing over the surface of the water. The size of wind waves is determined by the wind’s strength, duration, and fetch, which is the distance the wind blows without changing direction.

- Tsunami are giant waves that are actually the displacement of a large volume (and mass) of water caused by something like an earthquake or volcanic eruption under the ocean.

- Tidal waves are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

- Swells are a series of wind-generated waves that are not significantly affected by the local wind. Swells are often characterised by a long wavelength.

- Capillary waves, also known as ripples, are small waves whose dynamics and phase velocity are dominated by the effects of surface tension.

- Roll is a tilting (or swaying or rocking) motion from side to side, usually when the ship is pushed by wind and waves. The angle of list is the degree to which a vessel heels (leans or tilts) to either port or starboard at equilibrium, but with no external forces acting upon it. When “heel” is used it normally means that a boat leans over to one side in reaction to wind forces on the sails.

- Pitch is the up/down movement of a vessel along its longitudinal axis, so in simple terms it’s the front/back bobbing up and down. An offset or deviation from normal (i.e. the front or back (bow/stern) is too high or too low) is referred to as trim or being “out of trim”.

- Yaw is a rotation around the vertical, and can affect the heading or bearing.

- Surge is just a forward and backward motion when a ship is following a large swell.

- Sway is a side-to-side or port-starboard motion, often caused by lateral wave motion.

- Heave is an up and down motion, such as when a large swell pushes the ship vertically.

Pitch and roll tend to have the greatest impact on a ship’s comfort and safety, and a ship such as Le Lyrial will use its stabilisers to try to limit the impact on passengers.

Does a “calm” sea have a specific meaning?

- Sea state which is the general condition of the free surface on a large body of water, with respect to wind waves and swell, at a certain location and moment in time. A sea state is characterised by statistics, including the wave height, period, and spectrum. In fact ocean waves can be classified based on the disturbing force that creates them, i.e. the extent to which the disturbing force continues to influence them after formation, the extent to which the restoring force weakens or flattens them, and their wavelength or period. What this means is that waves will be different if caused by the sun or moon, storms, earthquakes, or different types of wind. There are codes that define the sea state, ranging from 0 (Absolute or glassy Calm so with no wave height), through 4 (Moderate with waves of 1.25 to 2.5 metres), then up to 7 (High with waves of 6 to 9 metres). There is also an 8 (Very High) and 9 (Phenomenal).

- Sea conditions can also be defined for water activities, which can be all clear (SC-AC), caution (SC-C), or danger (SC-D).

- Combined seas where the interaction of wind waves and swells means that the separate components are not distinguished.

- Swell is just waves that have travelled into an area after being generated by winds in other areas.

- Sea level is the height of seawater relative to a fixed datum or point on land. There are several types of sea level, including global, local, and mean sea level.

Why is the Antarctic a Continent?

We are on a cruise to visit the Antarctic, or is it Antarctica? What the difference?

The first thing to note is that the question “Why is the Antarctic a continent?” is wrong, and should be “Why is Antarctica a continent?“.

Antarctica

- Antarctica is the continent. It’s a large landmass (about 14 million square kilometres) covered by ice, sitting on its own independent tectonic plate (the Antarctic Plate). The Antarctic Plate moves independently from other continents, confirming its status as a separate landmass.

- It is defined geologically, politically (Antarctic Treaty System), and cartographically (on maps) as a distinct continent.

- Beneath the thick ice sheets, there is a continental crust (typically 35–40 km) with mountains (Transantarctic Mountains), valleys, and even subglacial lakes (e.g. Lake Vostok) and a subglacial mountain (Gamburtsev Mountain Range).

- Antarctica contains igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks, with some formations over 3 billion years old (Precambrian). This is the hallmark of an ancient continental crust.

- Antarctica has a completely unique climate. Its cold, dry, and windy environment makes it the driest, coldest, and windiest continent.

The Antarctic

- The Antarctic refers to a broader region that includes Antarctica but also surrounding areas that are influenced by Antarctica, including:

- Sub-Antarctic islands (like South Georgia, the South Sandwich Islands, and the Kerguelen Islands).

- The Southern Ocean.

- Any area south of 60°S latitude, which falls under the Antarctic Treaty System.

- It is an ecological and climatic term referring to everything within the Antarctic climate zone, not just the physical landmass of the continent.

What is South Georgia, and Where is It?

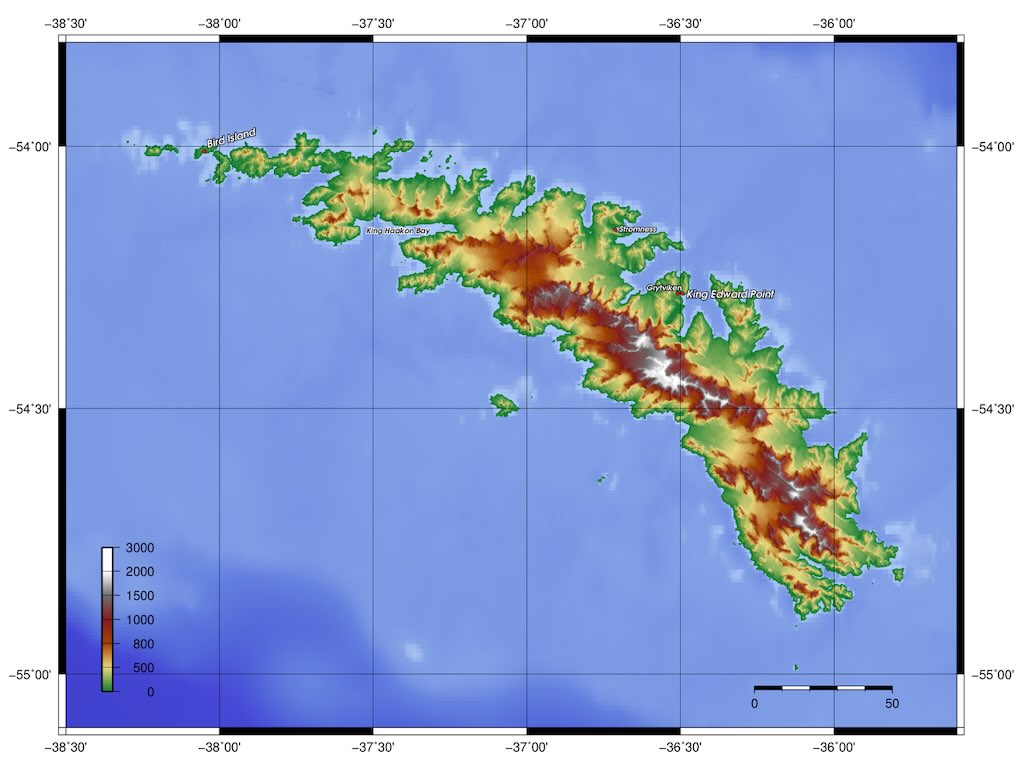

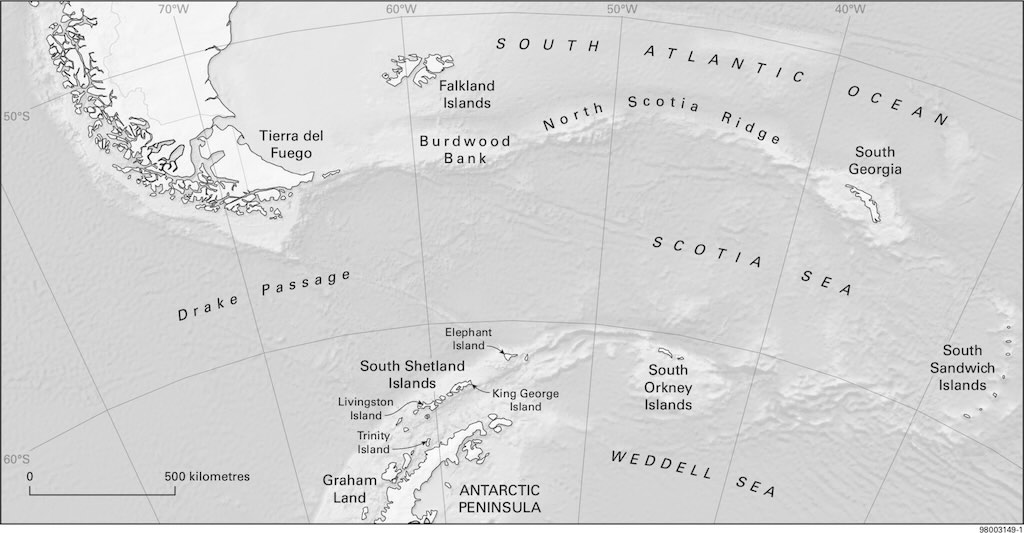

This is easy, because Wikipedia tells us that South Georgia (the little white area on the right) is an island in the South Atlantic Ocean that is part of the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. It’s just over 2,400-2,600 km from Ushuaia, and about 1,400 km from the Falkland Islands.

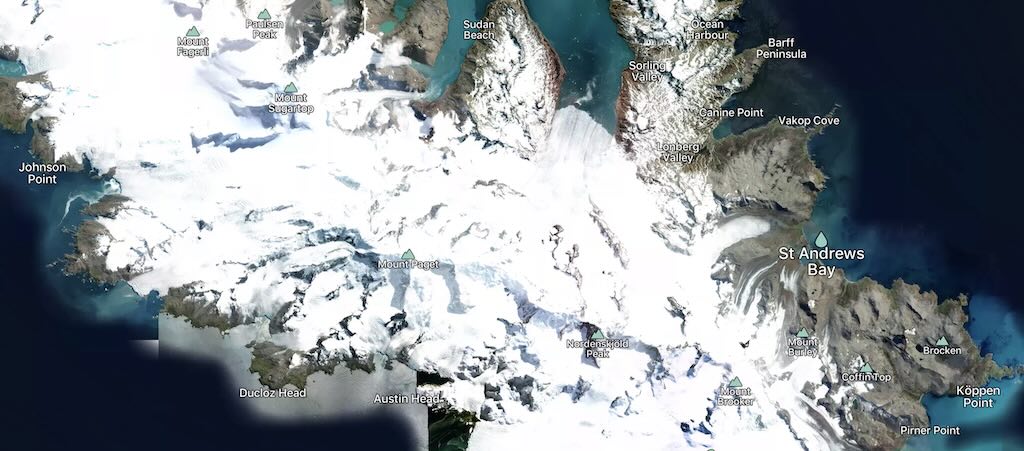

South Georgia is around 170 kilometres long and has a maximum width of 35 kilometres. The terrain is mountainous, with the central ridge rising to 2,935 metres at Mount Paget. The northern coast is indented with numerous bays and fjords, serving as good harbours. We will see that these harbours are our destination.

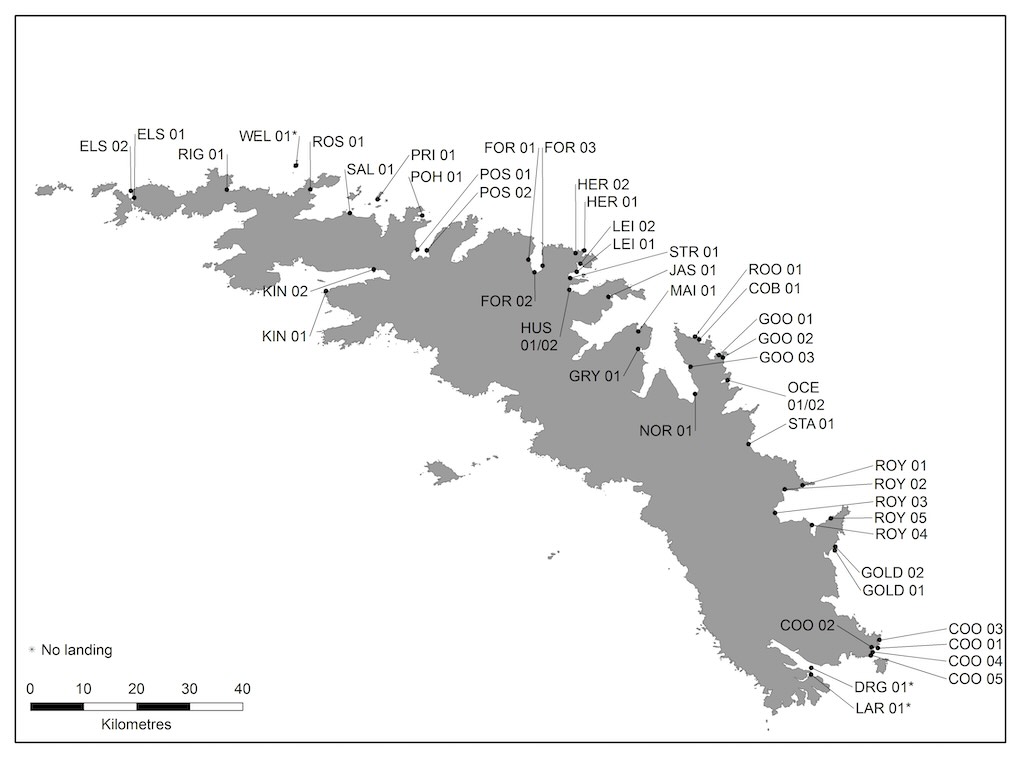

As seen above and below, it’s difficult to find an informative and reasonably detailed map of the island, but the below map is the most useful to see the different sites that were visited during this cruise, namely in order:-

- Rosita Harbour (ROS01)

- Salisbury Plain (SAL01)

- Fortuna Bay (FOR02)

- Grytviken (GRY01)

- Saint Andrews (STA01)

- Gold Harbour (GOL01)

The above map is from the official site of the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. The codes are the 49 approved visitor sites, but some approved sites are only suitable for Zodiac cruising (i.e. no landing).

South Georgia is home to over 160 glaciers cover about 56% of the island’s surface (e.g. Nordenskjöld Glacier, Neumayer Glacier). It has a subpolar maritime climate with temperatures rarely exceeding 10°C in summer, and winter temperatures averaging around -1°C. In addition the island is located in the Southern Hemisphere’s “Roaring Forties“.

South Georgia is an excellent example of an accretionary complex, containing metamorphic rocks, sedimentary rocks and volcanic rocks.

South Georgia’s wildlife is extraordinarily diverse and abundant, thriving in the nutrient-rich waters and harsh terrestrial environments of the island. Its ecosystems are among the most biologically productive on Earth, making the island a critical site for breeding, feeding, and resting for seals (Southern Elephant Seals, Antarctic Fur Seals, Leopard Seals and occasionally Weddell and Crabeater Seals), whales (Humpback, Southern Right, Blue, Fin and Orcas), penguins (King, Macaroni, Gentoo and Chinstrap), Albatrosses, Petrels, and the South Georgia Pipit.

As a first destination in this cruise, a mix of luxury and soft-expedition, it’s worth remembering the comments of Pete and Annie Hill who in 1995 cruised to South Georgia in their junk rigged yacht ‘Badger’. They wrote “Any yachtsmen sailing in these waters must be totally self-sufficient and prepared to extricate themselves from any eventuality. There are no rescue services and help should neither be sought nor expected from any of the few scientific bases. It should be remembered that it is impossible to replenish either stores or fuel”. And “hurricane force winds in apparently sheltered anchorages are not uncommon”, “weather conditions can change with extreme rapidity”, and “the accuracy of available charts should not be relied upon”.

Sub-zero temperatures are recorded every month of the year. The yearly average wind speed is around 5 m/s, so noticeable, but moderate. But it can occasionally rise to 50 m/s, which is equivalent to a category 3 hurricane.

What is the Scotia Sea and the Antarctic Convergence?

As a passing comment, we still say “setting sail” or being “under sail” or even “sailing the Seven Seas”, even when modern ships don’t have sails. This is just the same as saying a phone is “ringing” when modern phones no longer ring, and we even say someone has “dialled a wrong number” when we no long dial phone numbers. We might have said that a ship “oared out of port”, but we didn’t, however we did say a ship “steamed” out to sea, when steam engines became commonplace. Once the steam engine was replaced by diesel engines, it sounded a bit odd to say a ship “dieseled” out to sea, so the sail reappeared (we also avoided “turbining” out to sea and “fissioning” out to sea). So “sailing” has come to encompass the broader concept of maritime navigation, regardless of the specific means of propulsion. Some people might argue that the correct expression is that a ship is “under way”, and that “boating” and not “sailing” should be used for boats propelled primarily by a motor.

Starting in Ushuaia, we first sailed through the Beagle Channel, the strait between Chile and Argentina. The Beagle Channel is approximately 240 km from its western entrance near the Pacific Ocean to its eastern exit into the Atlantic Ocean. However, the portion navigated during a typical departure from Ushuaia toward the open ocean is about 70–80 km.

The channel was named after the ship HMS Beagle during its first hydrographic survey of the coasts of the southern part of South America which lasted from 1826 to 1830.

The route to South Georgia, including a small detour to the Shag Rocks, is around 2,600 km.

Although the Drake Passage is more commonly associated with trips to Antarctica, the route to South Georgia passes through a portion of it. The Drake Passage is infamous for rough seas, strong winds, and large swells, which is called the “Drake Shake” (stormy seas). However, our passage through this small portion of the Drake Passage was very calm, and this is called the “Drake Lake”.

The YouTube video “Drake Passage: The World’s Most Dangerous Sea Route” provides an accessible and interesting overview of the importance of the Drake Passage.

The distance covered in the Drake Passage before entering the Scotia Sea is about 500–600 km, depending on sea conditions and the ship’s navigation path. The Scotia Sea covers an area of approximately 900,000 square kilometres, and its average depth is about 3,000 meters. As a point of comparison, the Mediterranean Sea covers an area of approximately 2.5 million square kilometres, but only has an average depth of about 1,500 meters.

The Scotia Sea is a sea located at the northern edge of the Southern Ocean at its boundary with the South Atlantic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Drake Passage and on the north, east, and south by the Scotia Arc, an undersea ridge and an island arc system supporting various islands.

The Scotia Sea sits atop the Scotia Plate, which is a minor tectonic plate on the edge of the South Atlantic and Southern oceans. It’s thought to have formed during the early Eocene (around 40 million years ago) with the opening of the Drake Passage that separates Antarctica and South America. It is a minor plate whose movement is largely controlled by the two major plates that surround it, namely the Antarctic plate and the South American plate. Before the formation of the plate began 40 million years ago, these fragments formed a continuous landmass from Patagonia to the Antarctic Peninsula. At present, the plate is almost completely submerged, with only the small exceptions of South Georgia on its northeastern edge and the southern tip of South America.

It’s worthwhile stopping for a moment to remember that the archipelago of South Georgia represents one of the largest, most isolated land masses and continental shelf areas in the Southern Ocean, yet it was once situated adjacent to the Terra del Fuego region of South America. It probably migrated to its current position 45–20 million years ago.

The Scotia plate takes its name from the steam yacht Scotia of the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (1902–04), the expedition that made the first bathymetric study of the region.

The Scotia Sea is a critical part of the route and lies south of the Antarctic Convergence, where cold Antarctic waters meet warmer sub-Antarctic waters, creating one of the richest marine ecosystems on Earth. We can see that the sea is bounded by the North Scotia Ridge, an underwater mountain chain that influences ocean currents and marine life distribution. The ridge lies at depths typically ranging from 200 to 1000 meters below sea level.

The Antarctic Convergence is a marine belt encircling Antarctica, varying in latitude seasonally, where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the sub-Antarctic. And South Georgia is located in this sub-Antarctic region which encompasses islands and waters that lie north of the Antarctic Convergence. It is this convergence that creates nutrient-rich waters that support significant and diverse marine ecosystems on South Georgia.

The flow of water in the Antarctic Convergence is driven by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), which is the most significant current in the Southern Ocean and the strongest ocean current in the world. The result is that the total volume of water moving across the Antarctic Convergence is estimated to be around 130 million cubic meters per second. The press love to talk in terms of equivalent Olympic swimming pools, so this translates into 52 million Olympic pools per second!

Le Lyrial made a small detour to the dramatic looking Shag Rocks with are approximately 240 km west of South Georgia and stand isolated in the vast expanse of the Scotia Sea. These are six jagged islets that rise steeply from the ocean, and they were named after the Imperial shag (a type of cormorant).

South Georgia is an essential part of the cruise because its position in the sub-Antarctic zone, combined with its proximity to Antarctic waters, gives it a unique and rich biodiversity, making it a prime destination for scientific research and ecotourism. In addition it is not always accessible because recently there was an outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI, or bird flu) which led to concerns about environmental and biosecurity management.

Initially the highly pathogenic strain H5N1 was found in migratory bird species. Then it was detected in Gentoo and King Penguins. While the immediate impact during the current breeding season was limited, the virus posed a potential long-term threat to the dense penguin colonies. Later H5N1 was also detected in both elephant seals and fur seals.

It is for this reason that the South Georgia Government put in place strict biosecurity measures to protect its environment. We will describe how we had to comply with these checks to prevent the introduction of non-native species and diseases.

Calm night, woke around 04:00 local time.

Temperature 4°C and a 30km/h wind during the day.

Sunrise was at 03:34 and sunset at 20:46.

Yesterday the captain had mentioned a “calm” sea with a swell/houle of between 3-4 meters, however into the morning, the sea appeared even calmer. The expedition leader mentioned that it was possible that our trip to South Georgia would be particularly calm. We were following bad weather, and being followed by bad weather, but we had a particularly calm sea around us. Of course he warned that this could change.

The captain also mentioned that we were making good time, at around 13-14 knots (24-26 km/h). One knot (kn) is one nautical mile per hour.

Wikipedia tells us that until the mid-19th century, vessel speed at sea was measured using a chip log. This consisted of a wooden panel, attached by line to a reel, and weighted on one edge to float perpendicularly to the water surface and thus present substantial resistance to the water moving around it. The chip log was cast over the stern of the moving vessel and the line allowed to pay out. Knots tied at a distance of 47 feet 3 inches (14.4018 m) from each other, passed through a sailor’s fingers, while another sailor used a 30-second sand-glass (28-second sand-glass is the currently accepted timing) to time the operation. The knot count would be reported and used in the sailing master‘s dead reckoning and navigation. Although the unit knot does not fit within the SI system, its retention for nautical and aviation use is important because the length of a nautical mile, upon which the knot is based, is closely related to the longitude/latitude geographic coordinate system.

The day could have started with a morning stretching at 08:00, but instead I started the day with a light buffet breakfast on Deck 6.

At 09:30 to 10:00 the Ponant Parkas were distributed to Decks 3&4. It became evident that the daily agenda was already separated into two groups, French speaking and English speaking. And each language group was separated into two sub-groups, Decks 3&4 and Decks 5&6. My cabin was on Deck 4.

These Ponant Parkas are a “gift” from the company, and can be kept and taken home. My “status symbol” is now hanging proudly in Southern Andalusia.

So it appeared that I was de facto put in the English-speaking Deck 3&4 group.

At 11:00 there was a general presentation on the itinerary, and the presentation of the expedition team. The expedition leader, John Frick, discussed the weather for the next four days, and indicated a possible itinerary for the time in South Georgia.

This presentation was repeated in French at 11:30.

At 12:00 I received a lunch invitation for “singles” in the a la carte restaurant “Le Celeste” on Deck 2. There were five elderly men (including me), and Tino Carrillo, the “Directeur de Croisière“. Conversation was interesting with two New Zealanders, an Australian, and an Englishman who was now South African after spending 50 years there as a mining engineer. He had also lost his wife last year, so we had much in common.

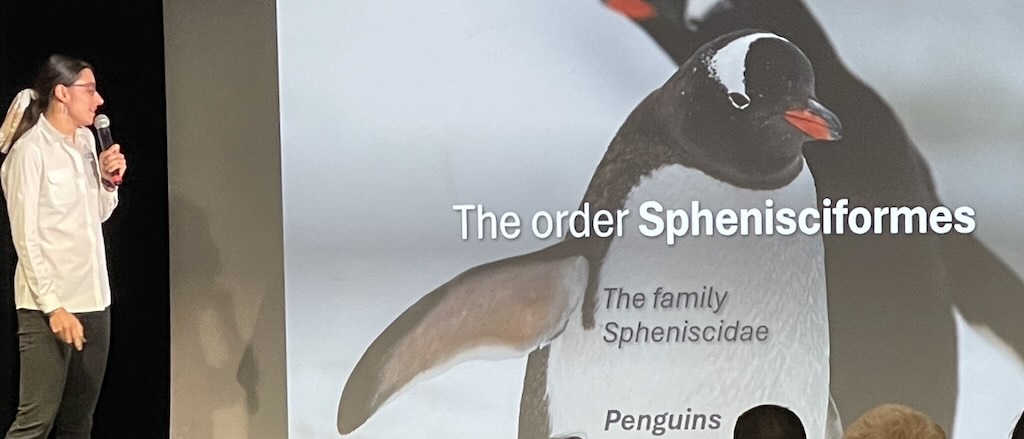

At 15:00 there was a presentation entitled “Seabirds, between sky and sea“, which was more interesting than I had anticipated.

It’s worthwhile mentioning here that seabirds are specifically birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. Seabirds generally live longer, breed later and have fewer young than other birds, and they invest a great deal of time in their young. Most species nest in colonies, varying in size from a few dozen birds to millions. Many species are famous for undertaking long annual migrations, crossing the equator or circumnavigating the Earth in some cases. They feed both at the ocean’s surface and below it, and even on each other. Seabirds can be highly pelagic, coastal, or in some cases spend a part of the year away from the sea entirely.

At 16:40 English speakers on Decks 3&4 were invited to a “Boot Camp” to collect their boots. We all turned up with our warm socks on, and tried on a couple of sizes. The advice was to go for a boot that was not too tight, because the trapped air around the foot helps keep in the heat.

Unlike the Ponant Parkes, the boots must be given back at the end of the trip. Outside each cabin a small mat appeared for everyone’s boots. Most people put the boots on the mat, but here and there some people decided to put their boots next to the mat.

At 16:00 to 17:00 there was tea-time served with classic French pastries and music. I managed a small cake as I was trying on my boots. Every day there was some kind of afternoon tea-coffee-cake moment (e.g. crêpe suzette, éclair, etc.), so I won’t be mentioning them again.

The high-point of the day was the Captain’s Gala Evening. English speakers from Decks 3&4 were expected at 18:45.

The first challenge was to decided what to wear. This Gala Evening was the high point of the cruise, and thus the suggestion was “smart with jacket and tie”. But there were also suggestions that it was not “so” formal, and the rule could be bent or even ignored. Some people chose just a white shirt, others smart casual, etc.

First we all had to queue up to have a photo taken with the captain. I didn’t keep my example, and I doubt he kept his. Then there was a glass of Champagne (which was constantly available at every instance during the cruise), with some canapés.

We were then all herded into the Theatre, accompanied by some (boring, middle-age) live music. I shouldn’t complain about middle-age, it only gets worse with time. But it was boring.

The Captain welcomed “his guests” and introduced key members of the equip, e.g. expeditions, food, engineering, etc.

Then we all headed into the a la carte restaurant Le Celeste for a “gala menu” served to all the passengers at the same time. I was fortunate to have found a place with some English speakers, i.e. two Australian couples, the South African mining engineer, and a younger couple from Wiltshire. It was a good evening.

I did not go to see the “Tribute to Frank Sinatra” at 21:30, nor did I listen to the live music from 22:15 to 23:15. Each evening there was some kind of entertainment programme from 21:00 to 23:00. I did not attend them, and won’t mention them again.

I took 50 mg dimenhydrinate just before bed. I didn’t feel any sea sickness the previous night, but it was better to be on the safe side. However despite the sea being “calm”, there were a few people who felt ill.

Calm night, woke around 06:00 local time.

Temperature 4°C and between 32-35km/h wind during the day.

Sunrise was at 03:44 and sunset at 20:09.

Again the day could have started with a morning stretching at 08:00, but I decided to started the day with a light buffet breakfast on Deck 6.

At 09:00 there was a mandatary briefing on the code of conduct ashore, including Zodiac instructions.

IAATO is the International Association of Antarctic Travellers (of which Ponant is a member). All members provide a mandatory briefing starting with the Antarctic Treaty, and going through to how to embark and disembark on the Zodiacs, a form of rigid inflatable boat.

The briefing was very well presented, and I think everyone started to realise that this trip was not a pleasure cruise, that there were lots of rules to be respected, and that it would be both a challenge (not impossible) and a unique experience.

Entering the Theatre we had to sign-in to show that we had attended the mandatory briefing, and leaving we were given our excursion life vests.

The excursion life vests were different from the on-ship life vests stored in the cabins. The expedition life vests went over the parkas, and were to always be worn on all excursions.

Tradition appeared to be that the expedition life vests were left outside the cabin with the boots.

At 10:15 there was a general knowledge quiz. I participated with three other passengers, and we tied top with 12/20 correct answers. The decider question was “how many US states have at least a portion of their area above the lowest latitude of the Canadian border”. We decided on 9 (I preferred 13), and our opponents decided on 7. How many do you think?

The answer was 24, so we all won a Ponant keyring.

At 14:45 there was a mandatory biosecurity session, where we ensured that our clothes and boots were really, REALLY clean (not necessary for any newly purchased clothes).

This involved removing any dirt, dust, etc. from all clothes to be worn on the excursions, including cleaning all velcro, turn-ups, etc.

At 15:45 there was an Introduction to South Georgia.

I took 50 mg dimenhydrinate just before bed.

Calm night, woke around 08:00 local time.

Temperature 3°C and between 16-19km/h wind during the day.

Sunrise was at 03:17 and sunset at 20:38.

I slept more than 8 hours, which had not happened since my wife had her minor stroke in June 2023. It would be the only night I slept anything close to 8 hours.

We were still sailing to South Georgia, and again, no morning stretching before breakfast.

This was the third day sailing from Ushuaia to the island of South Georgia, a total straight line distance of just over 2,400 km. However, with a small detour to see the Shag Rocks, the total distance was more likely to have been nearer 2,600 km. For context, the distance from Ushuaia to the Falkland Islands is about 890-930 km, and the distance between the Falkland Islands and South Georgia is 1390-1480 km.

At 11:15 there was a presentation on “Seals in Antarctica“.

At around 14:00 passengers were informed that the ship had taken a small deviation to see the Shag Rocks. Whilst often referred to as small rock islands, they are in fact six small islets.

They are small rock outcrops situated on the South Georgia Ridge, and they only have a peak elevation above sea level of about 75 metres (but stand in water more than 300 metres deep). There is no significant vegetation, but the rocks are covered by the guano of seabirds. The main wildlife found on the rocks are prions, wandering albatrosses and South Georgia shags.

At 15:30 there was a lecture “Sir Ernest Shackleton: the greatest survival history“.

At 17:45 there was a daily recap & briefing, about what had happened during the day, and what was planned for the next day.

I took 50 mg dimenhydrinate just before bed.

30 November 2024 - Rosita Harbour and Salisbury Plain (Day 5)

Calm night, woke around 05:00 local time.

Temperature between 0-2°C and between 6-9km/h wind during the day.

Sunrise was at 03:59 and sunset at 20:38.

Finally Le Lyrial had arrived at Rosita Harbour at about 07:45, and the first excursion could be organised.

Previously four different “colour” groups had been formed, based largely on language:-

Pink – Taiwan Chinese speaking (group of around 45 people)

Green – English speaking (group with around 40 people)

Yellow & Blue – French speaking

Colour groups were paired “Pink & Green” and “Yellow & Blue”. These groups would be used to programme landings, on one day “Pink & Green” would go first, then on the second day it would be first “Yellow & Blue” followed by “Pink & Green”.

Occasionally my group “Green” would be partnered with “Blue”.

The various briefings had explained how boarding would taken place, and how decontamination would proceed upon returning to the ship.

The idea was that as the second “colour pairs” embarked on their trip to the beach, the first “colour pairs” would be returning to the ship.

Each person had been reminded to wear warm, waterproof clothes, including the Ponant Parka, and the expedition life vest. I had naturally tried on and adjusted the life vest, immediately I received it.

Generally an excursion would last around 1 to 1½ hours, so with the Zodiac trips around 2 hours, more or less.

The excursions were more or less organised according to the same basic plan. Each group from a Zodiac, so 10 people, were “lead” by one of the expedition team. There was always a path (or target) outlined, and obviously a preset time to get back to the Zodiac for the return trip to Le Lyrial.

In some cases paths were indicated using sticks with small red flags. In other situations the flags were used to indicate areas where not to go, i.e. not too near elephant seals or to avoid the paths used by penguins.

Some leaders were more strict about keeping the group together, others less so. On this first excursion we all learnt that male elephant seals can be quite aggressive in defending their territory and mates. So it was important to take a path of “least aggression”, and the group leaders, equipped with simple wooden battens, were able to fend off the occasional signs of aggression. However we were warned that they could bite, and that due to the types of bacteria involved, it could be very serious.

For this first excursion to South Georgia I wore merino wool underpants, a merino wool set of underclothes (base layer), and a pair of inner socks. The mid-layer was a Mizuno polo-neck long-sleeve shirt and a pair of long merino wool socks. My outer-layer was a pair of waterproof trousers and the Ponant Parka. I also had a pair of warm, watertight gloves, a pair of inner lightweight gloves, and a hat. I took with me my iPhone and a pair of sunglasses.

Throughout the cruise and all the excursions I never had to add an additional layer. The weather was never too extreme, and on two occasions I left off the mid-layer because the sun was out and it was warm. I did find that the hat did not fit perfectly, it was originally my wife’s, so I changed it for my balaclava. I only wore my sunglasses on three excursions, and I never needed the goggles I had bought specifically for the trip.

Two specific recommendations. I would bring a set of inner soles for the boots, and I would bring a larger pair of gloves. The boots are like (not particularly) glorified wellingtons, and do little to protect the feet against the variable surfaces encounters on the excursions. The gloves were fine, but were a bit too tight when wearing thin inner gloves. Also I found that my finger tips got cold, and I would aim to have either a better inner glove plus a slightly bigger outer waterproof glove, and/or an even bigger outer glover allowing for a two pairs of thin inner glove liners.

We all had to carry our boots with us to the Main Lounge on Deck 3. There we put on the boots, and ensured that the waterproof trousers were outside the boots and as tight a fit as possible. It was also there that most people would “zip-up”, get ready, and put on their life vest.

The room key card (with name and unique ID code) now had a green circular tag on it, and had to be placed in a small closed pocket in the left sleeve of the Parka. There was a small transparent window which allowed the card to be scanned when leaving and returning to the ship. This way they knew who had gone ashore, and that everyone had returned safe and sound. Above we can see the scanning station.

Outside, behind the Main Lounge on Deck 3 there was an exterior deck. From there our ID was scanned and we went down to the Marina, the exterior Deck 2. It was from this deck that we embarked on the Zodiacs.

The Zodiacs used were a simple design, no wheelhouse, no benches, and no Bimini top. They were the basic model fitted with a simple outboard motor. There were a couple of Zodiacs with a steering column, there was one with two fitted outboard motors, and all the Zodiacs had Search and Rescue Radar Transponders (SARTs) fitted.

On Deck 2 we then had to walk through a disinfectant foot-bath, and climb one after another in to the Zodiac in groups of ten. The routine was “well-oiled”. A foot-box was placed in the Zodiac and people entered one-by-one. There were two people on the deck (in blue) and one person (white trousers) in the Zodiac to help. Any poles, bags, etc. had to be handed over separately, keeping hands free. Immediately each person had to sit on the topsides of the rigid air-filled side-tubes. Everyone was to slide along the tube, take their place, and hold on to the hand-rope. The pilot would then leave with their 10 passengers and the group leader.

We were very fortunate that conditions were almost perfect. There was almost no swell and the Zodiacs were very stable. However it was possible that the levels of the Zodiac and of the deck could change very brusquely. Passengers not immediately sitting, could be thrown on the floor and hurt, or worse. In the Zodiac it was important for passengers to sit, hold on, and then slide to their place on the side-tubes. Also it was important to continue to hold on tight, because the trip could be quite bumpy (or very bumpy).

How to Get In and Out of a Zodiac?

Some people are apprehensive about getting in and out (on and off) a Zodiac. There is quite a discussion on the Web, and there are videos. It looks as if the routine is more or less standard, but with small variations.

Above I’ve described the procedure for getting in to a Zodiac from the deck of a cruise ship, albeit with perfect weather. Now we will look at the “wet landing” on a beach.

The person steering the Zodiac drove front first up to the beach, where a team was there to stabilise the Zodiac and help each passenger disembark. There is a specific way to disembark and embark with a Zodiac.

The side-tubes are shaped and rise up at the front. So the technique is to slide (don’t stand) as far as possible up the side-tube to the front. Then looking back towards the sea, swing one leg over, find a good footing, then swing the other over, and stand. The reason you face the sea is that you can wait, if necessary, until the waves are calmer, before disembarking. Getting back in the Zodiac is basically the same. Stand next to the side-tube, looking out to sea, then swing one leg over, straddle the side-tube, hold on to the rope, and swing the other leg over. Then slide, don’t stand, to your place sitting on the side-tube. Always hold on. This routine implies that each side disembarks and embarks separately.

It might appear a bit complicated, but it’s an easy movement, and you learn it quickly. And there is always a helping hand from the crew when needed. However, we were also lucky with the weather, with calm seas, etc.

Returning to Le Lyrial

Returning onboard was not just the same routine done backwards. Disembarking from the Zodiac was more or less the same as embarking. One crew member boarded the Zodiac with a step, and helped each passenger climb out of the Zodiac. And there were two crew on the deck to “pull” the passenger onboard. If there was a noticeable swell, the Zodiac would bob up and down, so it was necessary to wait until it levelled with the deck.

The next steps were decontamination on the same deck (Deck 2). Just as it was important not to carry any invasive species on to the beach, it was also important to throughly wash the boots and waterproof leggings (and any walking poles, etc.). There were troughs with pre-installed brushes, and it was necessary to fully brush and clean off any waste picked up from the beach, etc. Then before returning to Deck 3, we had to again walk through a tray with disinfectant.

Climbing back up to Deck 3, we were scanned again onboard, and then staying outside, we removed our boots. After that it was possible to go back into the Main Lounge and back to the cabins. Boots were carried, and placed on the mat outside the cabin.

On the 30th November the first excursion was to Rosita Harbour, at 08:45 for Pink & Green Groups (followed by the Yellow & Blue Groups).

The Expedition Leader mentioned that the wildlife would be scarce on Rosita Harbour, so everyone was surprised to find the place teaming with both seals and penguins.

Rosita Harbour (Puerto Rosita) is a small sheltered bay 1.6 km on the west side of the Bay of Isles. Known for its stunning natural beauty, it is surrounded by rugged mountains, glaciers, and abundant wildlife. The area is a haven for seabirds, seals, and penguins, offering visitors a glimpse into the pristine Antarctic ecosystem. Its calm waters and scenic vistas make it a popular stop for expedition cruises exploring South Georgia.

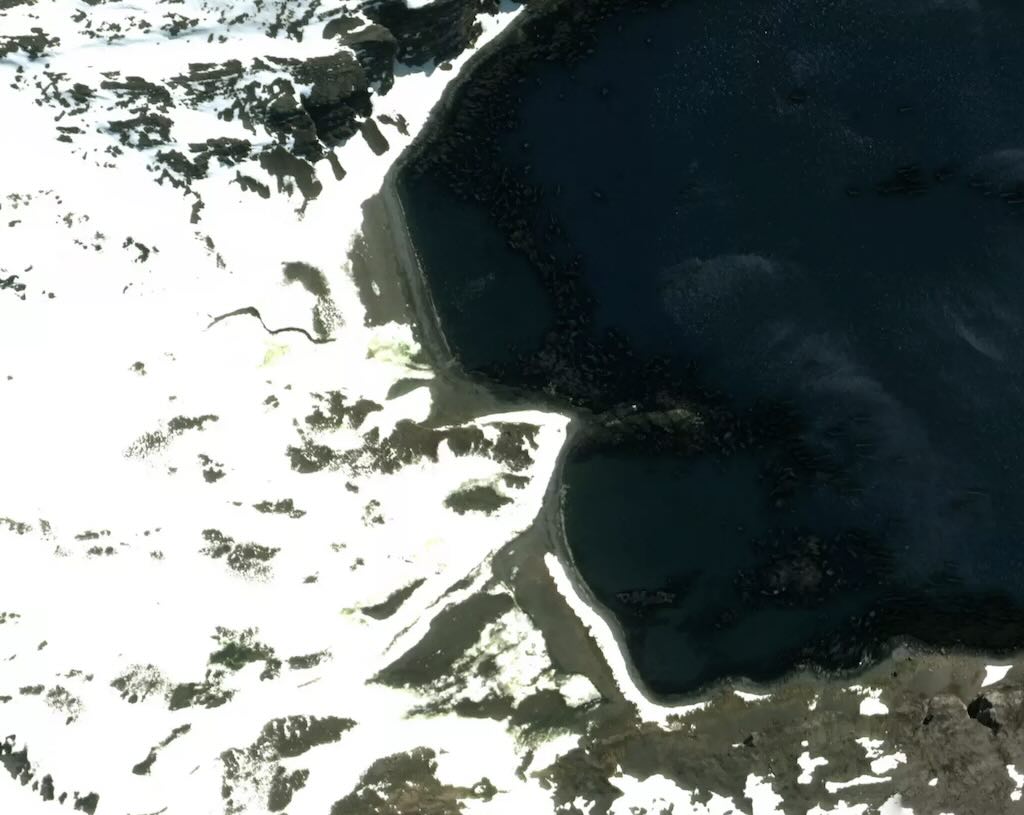

Below we have a satellite image for the Bay of Isles. The first excursion was in Rosita Harbour, which is the bay just above Ram Head on the left. The second excursion was in Salisbury Plain, just 4-5 km across the bay.

The Bay of Isles was discovered by Captain James Cook during his second voyage in 1775. Cook explored and charted much of South Georgia, making detailed observations of its coastline. This discovery was part of Cook’s broader mission to search for Terra Australis and expand geographical knowledge, which also included confirming the existence of South Georgia and claiming it for Britain. It is said that Cook named the Bay of Isles because of the numerous small islands scattered across the bay. However there is also a mention that the name was given by the Discovery Investigations, a British scientific research program in the early 1920s and 1930s. In this case the name also was to reflect the numerous islands scattered across the bay, but also emphasising its geographic and navigational significance. The Discovery Investigations named many features on South Georgia during their mapping and biological surveys.

Rosita Harbour is said to have been first charted during the early period of South Georgia’s exploration. It is believed to have been discovered and named by Carl Anton Larsen, a Norwegian explorer, whaler, and captain of the ship Jason. Larsen extensively explored South Georgia during his 1893–1894 expedition, mapping significant parts of the coastline and naming various geographical features. However, specific historical details about the name’s origin are not well-documented, and it’s possible that the name was given by British whalers or surveyors during earlier exploration or whaling activities in the region.

The terrain was quite difficult. One part of the walk was covered by what looked like between 10 cm and 20 cm of fresh snow, covering an uneven ground including small hidden streams. Plenty of opportunity to sprain an ankle or twist a knee. Fortunately there were no accidents, but we all “got the message” to be careful.

Naturally there were no paths, etc., and we had to watch where we put our feet. Secondly, we had to avoid aggravating the elephant seals. Thirdly, we had to keep our distance from the wildlife, despite some of the penguins being quite inquisitive. This meant keeping about 5 meters from the penguins, and around 10-15 meters from the more aggressive male elephant seals.

The second excursion, to Salisbury Plain, was at 14:30 for Pink & Green Groups (followed by the Yellow & Blue Groups).

Just as a word of warning. The satellite images are taken at different times and don’t always show the exact physical conditions found on the day of the excursion.

Salisbury Plain, sits on the northern coast of South Georgia within the Bay of Isles, and is one of the island’s most remarkable wildlife viewing spots. It is a broad coastal plain framed by the Grace Glacier to the west, Lucas Glacier to the east, and overlooked by Mount Ashley to the south. The plain itself consists of tussock grasslands, which create an ideal habitat for the region’s abundant wildlife.

In late November, which corresponded to spring in the Southern Hemisphere, Salisbury Plain was teeming with life as the breeding season was in full swing. Salisbury Plain hosts one of the largest King Penguin colonies in the world, with over 100,000 birds. At this time of year, the adults were actively incubating eggs or caring for newly hatched chicks. Large harems of female Southern Elephant Seals were on the beaches, with their pups born earlier in the season now becoming more independent. Dominant males (known as “beachmasters“) sat guarding their harems, often engaged in dramatic, loud displays. There were also Fur Seals on the beaches, preparing for their own pupping season.

Salisbury Plain was probably discovered during the detailed mapping of South Georgia during the 19th century as sealers and whalers began visiting the island. The name was probably first used by British explorers or whalers, drawing a parallel to the Salisbury Plain in England, known for its flat and open landscape. However, specific records detailing who named it and why are rare and imprecise.

I’ve no doubt that there is a link between this place name and Salisbury Plain in England, but Salisbury has been used numerous time to name ships, already in 1781, and there have been seven naval ships named HMS Salisbury. And not forgetting that there are Salisbury Island’s in Russia, Canada and Australia.

Today the name Salisbury Plain has since become iconic due to its extraordinary wildlife and its role as a prominent breeding ground for king penguins and seals.

At 18:30 there was a daily recap & briefing, about what had happened during the day, and what was planned for the next day.

I took 50 mg dimenhydrinate just before bed.

What Do We Know About the Elephant Seal?

Elephant Seals are large, highly adapted pinnipeds (a type of marine mammal) in the family Phocidae (Earless Seals). They belong to the genus Mirounga, which today comprises two extant species:-

Southern Elephant Seal (Mirounga leonina):

The larger of the two species, with extreme sexual dimorphism. Adult males can exceed 5 meters in length and weigh up to 4 tons, whereas females are considerably smaller (generally under 1,000 kg).Northern Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris):

Found primarily along the eastern Pacific coasts of North America, these are smaller than their southern relatives.

The current Southern Elephant Seal evolved from ancestors that lived in warmer, temperate marine environments during the Miocene (23 to 5.3 million years ago). Fossil evidence suggests that these ancestral forms were relatively smaller, with body plans similar to other pinnipeds adapted to moderate climates. Over time, as the global climate cooled and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current was established, the Southern Ocean underwent dramatic cooling (from roughly 15–20°C to around 0–2°C today). This climatic shift imposed new selective pressures that led to several key adaptations:

Increased body size

Following Bergmann’s rule, larger body sizes evolved in cold climates because a lower surface area-to-volume ratio reduces heat loss. Modern Southern Elephant Seals are among the largest pinnipeds, which helps them conserve body heat in frigid waters.

Enhanced insulation

Their thick, multi-layered blubber provides critical insulation against cold water. Genetic changes related to lipid metabolism and adipogenesis (formation of fat cells from stem cells) likely promoted the development of this extensive fat layer, ensuring efficient thermal regulation during long, deep dives.

Improved diving physiology

Adaptations in muscle composition, such as high concentrations of myoglobin (an iron– and oxygen-binding protein), allow for extended dive durations. These physiological modifications not only support foraging in deep, cold waters but also assist in maintaining core body temperature during prolonged submersion.

Behavioural and reproductive adjustments

Changes in migratory and haul-out behaviour allowed them to exploit optimal breeding and foraging grounds. Hauling-out means temporarily leaving the water between periods of foraging. For example, the shift to breeding on subantarctic islands like South Georgia minimised exposure to harsh open-ocean conditions and maximised access to productive feeding areas.

These changes, occurring over millions of years, transformed an ancestral pinniped lineage into the highly specialised, ice-adapted Southern Elephant Seal we see today.

Southern Elephant Seals can dive to depths exceeding 1,500 meters and remain submerged for over two hours, an adaptation that enables them to exploit deep-ocean prey (especially squid and lanternfish). Their physiology is tailored for prolonged apnea, with high myoglobin concentrations in their muscles and efficient oxygen storage mechanisms. As a point of comparison, Sperm Whales can routinely dive for 45–90 minutes (at depths of around 800–1,200 meters), however many other species of whales (such as Blue Whales or Humpbacks) typically dive for shorter periods, usually around 10–15 minutes, though they can sometimes stay submerged for 30 minutes or more when necessary (and only go down a few hundred meters).

We only see elephant seals on the beach, but a male makes extended at‐sea foraging trips, which can last several weeks to months. They typically spend about 75–85% of their time underwater. In practical terms, that means they may be actively diving for roughly 18–20 hours per day, interspersed with relatively brief surface intervals for recovery. The females typically spend about 70–80% of their time underwater actively foraging, which works out to roughly 16–19 hours per day of diving with only short surface intervals between dives. Studies suggest that on average a female may need to consume roughly 7–8 kilograms of prey per day whereas male are much larger and, as a result, have substantially higher energy requirements compared to females. Estimates indicate that an adult male may need to consume roughly 20–30 kilograms of prey per day.

Elephant Seals are highly polygynous. Males establish territories on sandy beaches or rocky outcrops, where they gather harems of females during the breeding season (they are often informally referred to as “beachmasters”). The remarkable sexual dimorphism seen in the species is linked to this competitive breeding strategy.

Southern Elephant Seals are not “Antarctic” in the sense of exclusively breeding on the icy mainland, they are widely distributed in the Southern Ocean and are particularly associated with subantarctic islands and coastal areas of Antarctica.

South Georgia hosts the largest and most important breeding aggregations of Southern Elephant Seals. One of the reasons is that the rich upwelling systems and productive shelf waters surrounding South Georgia support abundant prey, which in turn sustains these large populations.

Although smaller in scale than South Georgia, several of the South Shetland Islands have been recorded as seasonal haul-out sites. Some islands may host transient breeding aggregations, but overall, the primary breeding sites remain on larger subantarctic islands like South Georgia.

The Antarctic Peninsula is an important haul-out areas, especially during the austral summer. While robust, long-term breeding colonies are less common than on South Georgia, many Southern Elephant Seals use the peninsula’s coastal regions as resting areas during their extensive foraging migrations.

Along sections of the Antarctic mainland, particularly where the coast is not perpetually covered by fast ice, Southern Elephant Seals have been observed hauling out. These occurrences tend to be opportunistic, associated with foraging trips and the dynamic nature of the pack-ice edge.

1 December 2024 - Fortuna Bay and Grytviken (Day 6)

Calm night, woke around 04:00 local time.

Temperature around 1-2°C and around 8km/h wind during the day.

Sunrise was at 03:54 and sunset at 20:38.

Excursion - Whistle Cove, Fortuna Bay

The third excursion, to Whistle Cove in Fortuna Bay, was at 08:00 for Pink & Green Groups (the Yellow & Blue Groups had left at 06:40).

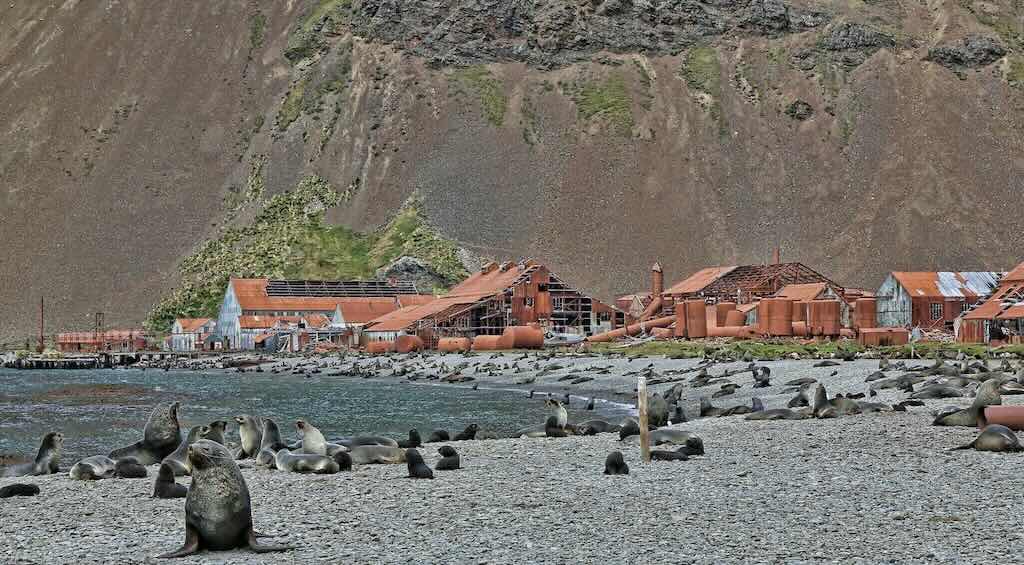

Fortuna Bay is about 5 km long and about 1.6 km wide, and is situated on the north coast of South Georgia. It was named after the Fortuna, one of the ships of the Norwegian–Argentine whaling expedition under C.A. Larsen which participated in establishing the first permanent whaling station at Grytviken, South Georgia, in 1904–05. The bay is surrounded by dramatic mountains and glaciers, and is known for its abundant wildlife and historical significance.

Whistle Cove is nestled in the southeastern corner of Fortuna Bay. It offers a more sheltered environment compared to the wider bay, making it a haven for wildlife and a favourite spot for expedition landings. The cove is home to part of Fortuna Bay’s massive king penguin colony. Both fur seals and elephant seals are abundant on the shores, particularly during the breeding season.

It is widely accepted that the name Whistle Cove is connected to the wind. Natural acoustic phenomena are common in polar and sub-polar regions, where the combination of wind, ice, and rocky landscapes produces unique soundscapes. It is believed that the name derives from the whistling sounds produced by strong winds funnelling through the surrounding cliffs and mountains, and was probably coined by early explorers, sealers, or whalers.

There was an optional “Shackleton Walk“, a 6 km walk over an uneven and slippery route, that left at 07:15.

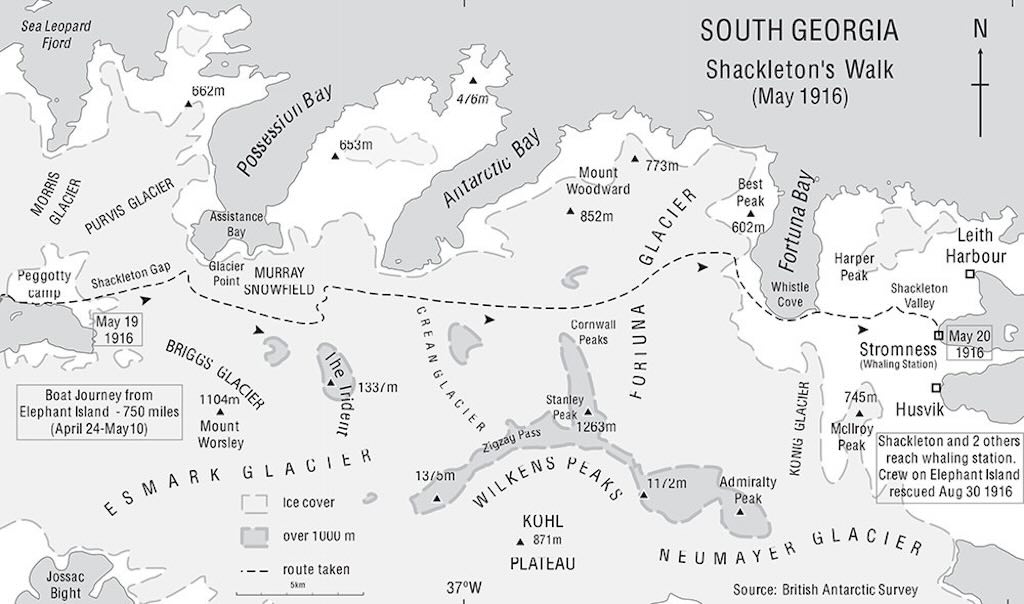

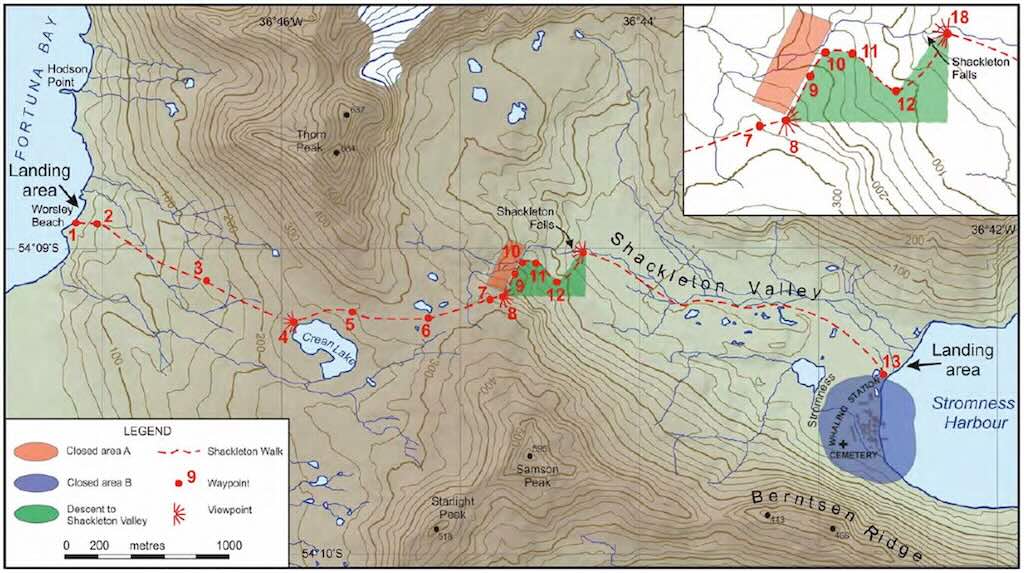

The Shackleton Walk, also known as the Shackleton Hike, is an iconic trek on South Georgia Island, retracing part of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s epic journey during the 1916 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. This runs approximately 6 km from Whistle Cove to Stromness in Stromness Bay and typically takes around 4 hours to complete, depending on conditions. This trek marks the final leg of Shackleton’s 36-hour journey (see above) over the island after his open-boat voyage from Elephant Island. Reaching Stromness marked the beginning of the rescue of his stranded crew.

I’ve tried to describe the walk below, based on documents of the South Georgia Government.

The hike started with a Zodiac landing at Whistle Cove, and the trail crosses snowfields and rocky outcrops (the landing area was slightly different from the above). The different numbers in red are waypoints to help guide the route.

The final descent is one of the most famous sections, offering stunning views of Stromness Bay and the abandoned whaling station.

The hike is considered moderate to challenging due to uneven terrain, potential snow, and steep sections. The key feature (and problem) was that it was not possible to go back, since the ship would move to pick everyone up in Stromness Bay.

For some people the Shackleton Walk is more than just a hike, it’s a step back into history.

The fourth excursion, to Grytviken, was at around 16:00 for Pink & Green Groups (the Yellow & Blue Groups had left at around 14:30).

I have posted a separate description of Grytviken, but I will describe here the decontamination session that took place before this excursion.

The Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands has established a severe (some would say draconian) bio-decontamination control on all people visiting the islands.

At 13:45 Pink & Green Groups (Yellow & Blue Groups were first at 13:00) started a complete bio-decontamination session, checking boots, all external clothing’s, etc. for any possible bio-contaminants.

Around 14:30 the Yellow & Blue Groups were first checked before going down to the Zodiacs. There the South Georgia authorities performed another control, one-by-one. Unfortunately this meant that more or less all the French-speaking contingent were controlled. I understood that the rule was that 75 from 90 controls had to be negative, otherwise the ship and passengers would not be allowed to disembark and the ship would have to leave the islands waters. I also understood, that from the first 90 controls 79 passed, so we were all allowed to disembark and visit the only partially-inhabited site on South Georgia.

At 18:45 there was a daily recap & briefing, about what had happened during the day, and what was planned for the next day.

I took 50 mg dimenhydrinate just before bed.

2 December 2024 - Saint Andrews and Gold Harbour (Day 7)

Calm night, woke around 03:30 local time.

Temperature around 2°C and between 3-6km/h wind during the day.

Sunrise was at 03:49 and sunset at 21:32.

The fifth excursion, to Saint Andrews Bay, was at 08:10 for Pink & Green Groups (the Yellow & Blue Groups left at 09:50).

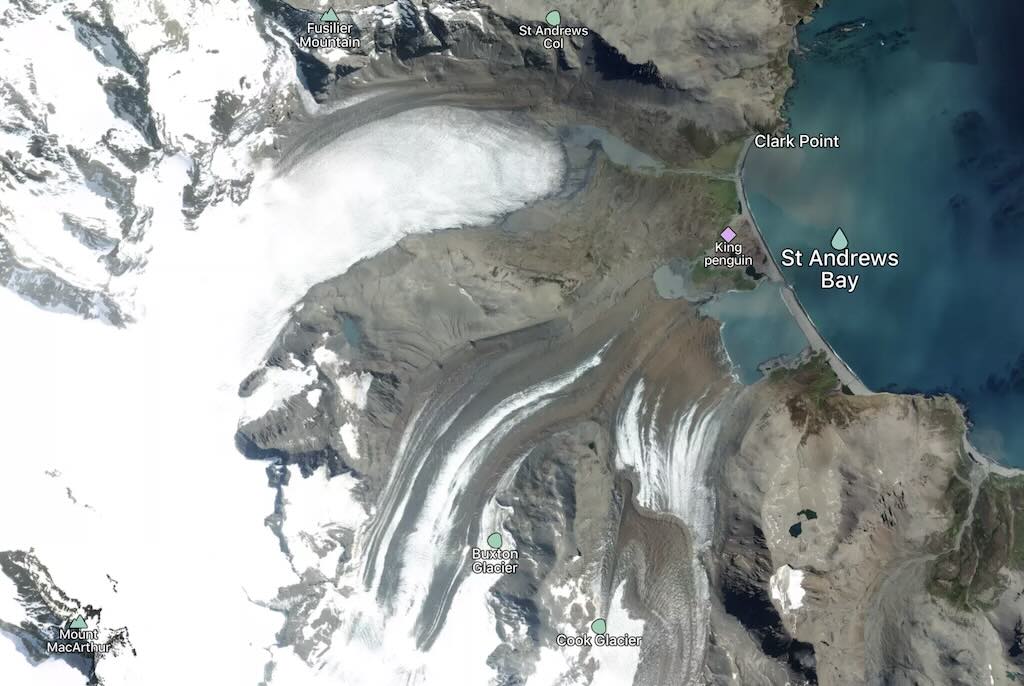

Saint Andrews Bay is flanked by steep mountains and hills, with peaks reaching several hundred meters. It is bordered by glaciers, including the Cook Glacier, which historically fed into the bay but has retreated due to climate change. The bay provides a good example of glacial geomorphology.

Several meltwater streams and rivers flow into Saint Andrews Bay from surrounding glaciers, contributing to a mix of fresh and saltwater in the intertidal zone. It is these water sources that create a rich mix of nutrients that support an abundant marine life, including krill, which is a key food source for many species in the region.

The Bay is a biodiversity hotspot. It hosts one of the largest king penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus) colonies in the world, with numbers exceeding 100,000 breeding pairs. Other notable species include fur seals, elephant seals, and a variety of seabirds such as albatrosses and skuas.

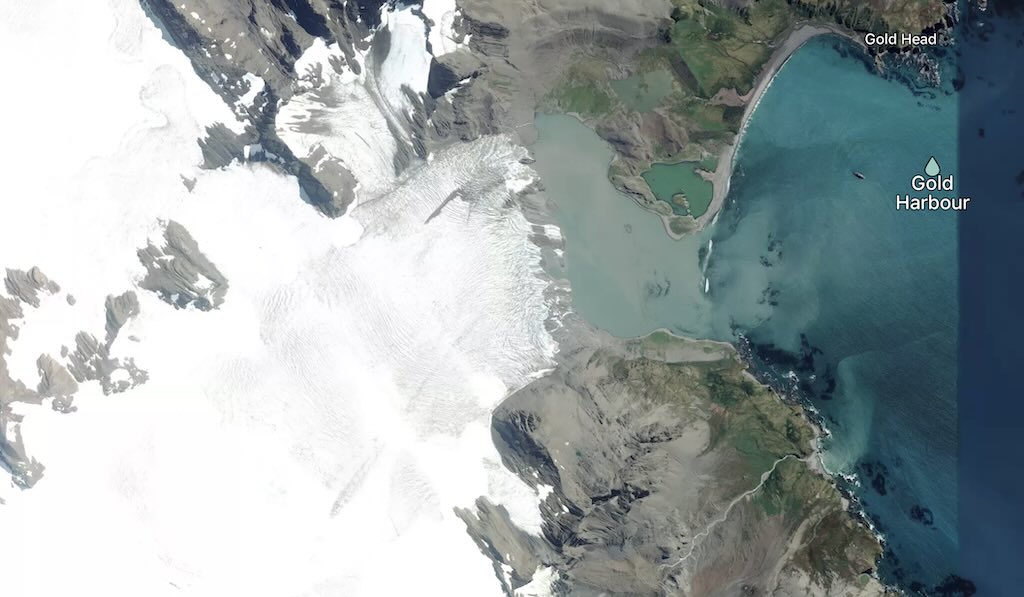

The sixth excursion, to Gold Harbour, was at around 14:30 for Pink & Green Groups (the Yellow & Blue Groups left later).

The harbour is a semi-circular bay, framed by steep cliffs, coastal plains, and glacial deposits. The area is dominated by the Beresford Glacier (a so-called tidewater glacier), which terminates close to the shoreline.

The glacier stretches approximately 3–5 km in length, and its surface is characterised by crevassing, particularly near its terminus, due to the steep gradient and ice flow dynamics. We can see on the left the waterfall that is a feature of the glacier.

The name Gold Harbour is not about gold deposits, but is probably linked to the striking golden light that bathes the area during certain times of the day, particularly at sunrise. This effect occurs because the bay is oriented to face the southeast, allowing the low-angle rays of the rising sun to illuminate the cliffs, glaciers, and surrounding landscape. The combination of light reflecting off the ice and water enhances the warm golden hues.

The Beresford Glacier was named after Lord Charles Beresford (1846–1919), a prominent British admiral and politician. The naming of geographical features like the Beresford Glacier reflects the British heritage of South Georgia, as the island was explored and mapped extensively by British expeditions during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

At 18:00 there was a daily recap & briefing, about what had happened during the day, and what was planned for the next day.

Around 18:00 Le Lyrial set sail for Penguin Island, one of the smaller of the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica

I took 50 mg dimenhydrinate just before bed.

What's Life Like as a King Penguin?

I am going to try to create a first-person perspective, or more precisely a first-penguin perspective, of the life of a King Penguin in a colony such as the one on Salisbury Plain.

But first, let us set the scene. King Penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) are renowned for forming some of the largest and most densely populated breeding colonies among avian species. These colonies, such as the one on South Georgia Island’s Salisbury Plain, can host over 100,000 breeding pairs, creating a dynamic and complex social environment.

Colony structure and social behaviour

King penguin colonies are typically established on large, sparsely vegetated coastal plains, which provide ample space for the dense congregation of birds. The social structure within these colonies is intricate, with individuals engaging in various behaviors to maintain their territories and social bonds. Despite the absence of physical nests, king penguins exhibit strong territorial instincts, maintaining a pecking distance from their neighbours to reduce conflicts.

Communication is vital in these bustling colonies. King penguins utilize a unique two-voice system produced by their syrinx, allowing them to emit complex vocalizations. These calls are essential for individual recognition between mates and between parents and chicks amidst the cacophony of the colony. Visual displays, such as stretching to full height and trumpeting calls, are also employed during courtship and territorial disputes.

Breeding cycle

The breeding cycle of king penguins is notably prolonged, spanning approximately 14 to 16 months from egg-laying to the fledging of the chick. This extended period means that, typically, a pair can only successfully rear two chicks every three years. Breeding is not strictly seasonal, resulting in colonies being occupied year-round with adults at various stages of the breeding process.

After courtship, which involves mutual displays and vocalisations, the female lays a single egg. Both parents share the responsibility of incubation, taking turns holding the egg on their feet under a skin flap for about 55 days. Upon hatching, the chick remains on the parents’ feet for warmth and protection for the first 30 to 40 days. As the chick grows, it joins a crèche, a group of young penguins, that provides communal warmth and protection, allowing both parents to forage simultaneously.

Foraging and diet

King penguins are exceptional divers, capable of reaching depths exceeding 300 meters and staying submerged for up to 10 minutes, though typical dives are shallower and shorter. Their diet primarily consists of small fish, particularly lanternfish, supplemented by squid and krill. Foraging trips can extend up to 500 kilometers from the colony, especially during chick-rearing periods when the demand for food is high.

Predation and challenges

Within the colony, eggs and chicks are vulnerable to predation by birds such as skuas and giant petrels. Adults face threats at sea from leopard seals and orcas. Despite these natural challenges, many king penguin populations are currently stable or increasing. However, environmental changes and human activities continue to pose potential risks to their habitats and food sources.

Understanding the intricate social structures, breeding behaviors, and ecological challenges of king penguin colonies provides valuable insights into their resilience and the delicate balance of their sub-Antarctic ecosystems.

I am King