This is a description of my visit to MUDAM, the Musée d’art moderne Grand-Duc Jean, in Luxembourg (Feb. 2026). It is a museum of modern art, that stands on the site of the old Fort Thüngen, on the southwestern edge of the Kirchberg-plateau.

I had visited it in the past, but never wrote up my impressions. This time I decided to write a visit report, and naturally, I found that a large part of the museum was closed, preparing for a new exhibition. This did not stop me from visiting the impressive architecture, and the temporary exhibitions on show (on floor +1).

The name tells us that this is a museum of Modern Art, which should mean covering the period ca. 1860 to 1970, i.e. Impressionism through Abstract Expressionism to early Minimalism. But in practice, my impression (sorry) is that it’s more a stage for Contemporary Art, i.e. art of the current world.

The reality is that for a museum that opened in 2006 its impossible to create a modern art collection, or to enhance an existing collection. There are very few works in circulate, the competition for them is too intense, and state budgets just cannot keep up. And provenance and ownership is increasingly a minefield.

So MUDAM does what most new museums do. It collects and/or presents what is still possible, namely, local artists, living artists (also becoming too expensive), Installation Art, Commissions, and New Media Art.

The History of a Modern Art Museum

I think that in the late 80s Luxembourg started to think about investing heavily in its cultural infrastructure, to align itself with other European capitals. MUDAM opened in 2006, but there was also Nationalmusée um Fëschmaart (renovated 2002-2014), the Philharmonie (2005), Villa Vauban (renovated 2010), Musée Dräi Eechelen (2012) and NaturMuseé (reopened 2017).

The Luxembourg government decided in 1989 to establish a modern and contemporary art museum. The story goes that the government identified a short list of international architects, and I. M. Pei was chosen from that list, largely on reputation and relevant experience (remembering that he had been the architect for the glass-and-steel pyramid for the Louvre in Paris, and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha).

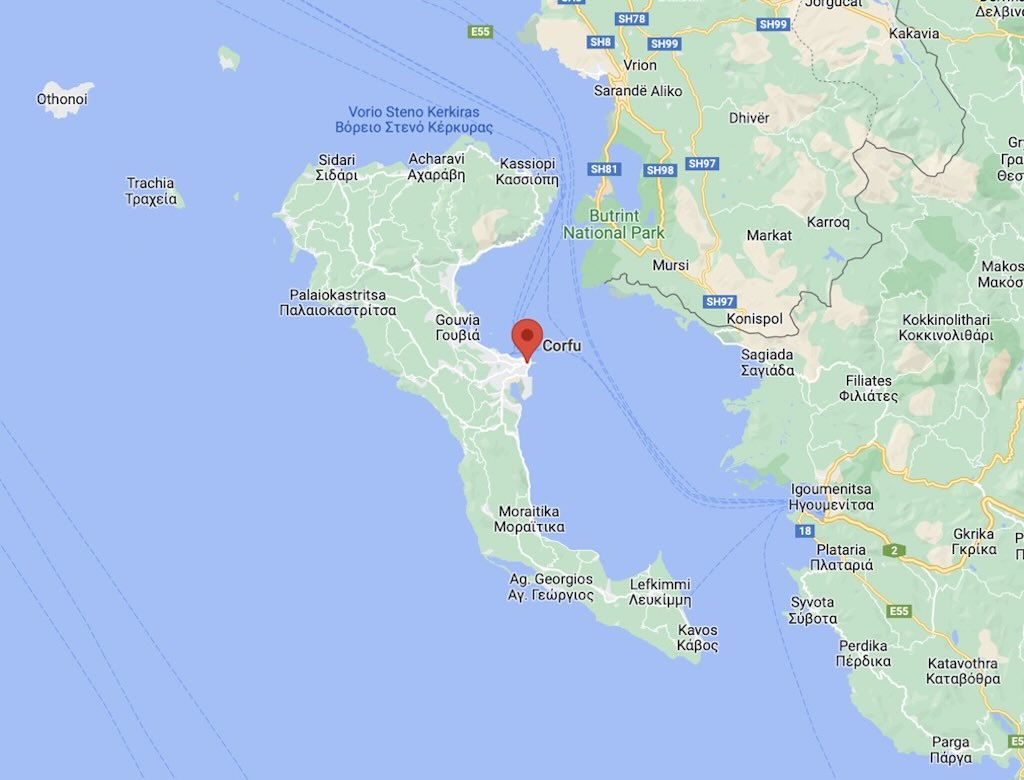

Multiple locations were considered, including a site at the Saint-Esprit plateau sandwiched between the Alzette and the Pétrusse, and very close to the centre of Luxembourg City. Pei was asked to assess options and, according to planning discussions, he expressed a preference for the site near the remains of Fort Thüngen (“Dräi Eechelen”). The site offered a strong visual and symbolic link between Luxembourg’s historical past and its European future (near European institutions), and a generous green setting with views over the old city. It was controversial at the time, partly due to heritage preservation concerns. But it was argued that the investment would ensure that the dramatic historic site of Fort Thüngen would be preserved and enhanced.

An official Luxembourg government infrastructure planning document from 2005 noted that the MUDAM was expected to open end of 2005. This was in the context of a series of major cultural infrastructure investments tied to Luxembourg’s 2005 EU Presidency. But MUDAMs opening in mid-2006 coincided nicely with Luxembourg being 2007 European Capital of Culture (along with Sibiu in Romania).

In its first full year (2007) it attracted around 90,000 visitors, and since then appears to attract a constant 100,000 to 130,000 visitors per year. It’s pointless comparing this with the ~3,000,000 for Centre Pompidou (Paris) or the ~4,700,000 for Tate Modern (London), or even the ~870,000 for Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). But it can be compared with ≈ 308,000 that visit Centre Pompidou-Metz, or the ≈ 147,000 for M HKA Antwerp, or the ≈ 110,000 for MACA (Alicante).

It’s often the case that any large new “modernist” building on a heritage site will be challenged, and this was also the case for MUDAM. Some critics thought the museum too large and too expensive for the historic site. Others feared the design would damage or overwhelm the remains of the historic fortress. The architect I. M. Pei did revise plans after these public and professional objections.

The construction was formally delayed by a Gerichtsprozess (court case). Firstly, heritage advocates argued that the museum’s footprint and construction methods would hurt the historical remnants they were meant to preserve. The courts had to consider whether the plans legally respected the protection of the old fort site. Then there was a legal dispute over the building stone used. Pei specified a “magny doré” limestone for the Mudam façade, the same type used on parts of the Louvre. At one point, the tribunal had to investigated whether the delivered stone actually met those specifications. That led to litigation over contract compliance and whether suppliers and builders had met the legally required material standards. Then there were allegations of irregular public tendering. Parts of the public procurement process were challenged (how construction contracts were awarded). Some competitors argued that bids were not transparently or fairly managed. That allegation itself became the subject of legal challenge and review. This kind of procurement litigation was enough to halt/delay public works until the courts decide. These court proceedings did not permanently stop the project, but they delayed the completion until mid-2006.

And of course, there were cost over-runs, and design changes, etc. The design was revised during planning, mainly because the site was not neutral ground. There were negotiations over how much of the historical fort could be touched, revealed, or built over.

The original legal spending cap (1997) was 2,780,000,000 Luxembourg francs for the construction project as authorised by law. That’s about €68.9m. A later official government communication (June 2006) states that construction began in January 1999 with a budget of €88 million. It’s also stated that for the Parc Dräi Eechelen (the environment around MUDAM) the authorised budget was €16.4m, but only ~74% was used. However, a pedestrian bridge was not built (it was finally built and opened in 2025).

MUDAM Technical Information

Architect – Ieoh Ming Pei, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners

Lead Architect – Tim Culbert

Associate Architect (local) – Georges Reuter Architectes

Landscape Architect – Michel Desvigne

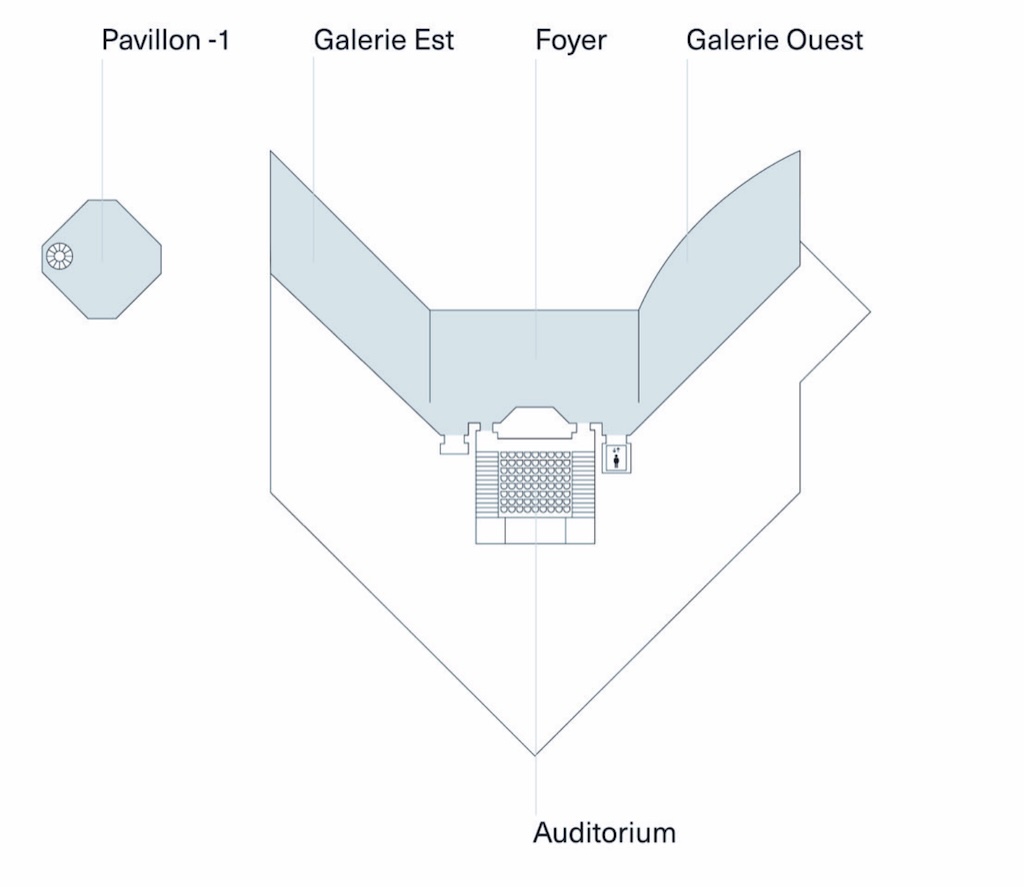

Total built-up area – 10.500 square-metres

Public space – 6.000 square-metres on three levels

Exhibition space – 4,000 square-metres on three levels

Budget – €88 million (2006)

The Exterior

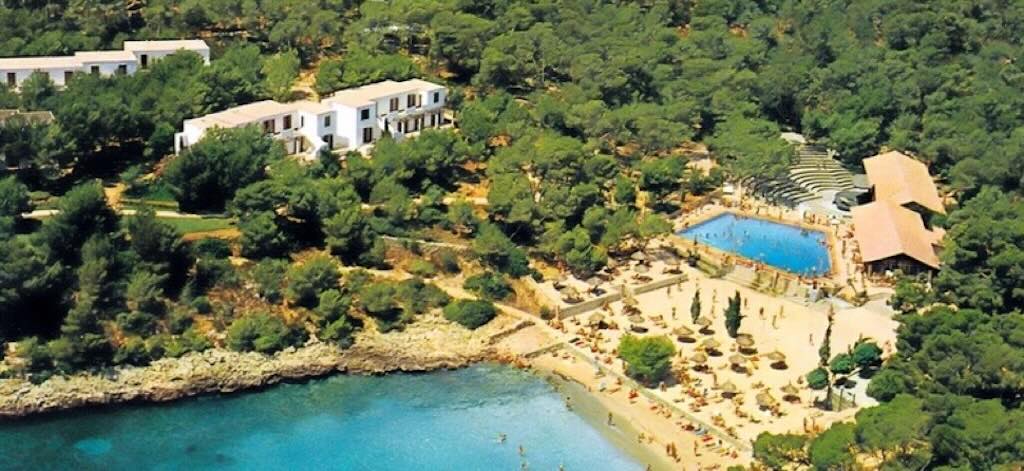

The V-shaped building is built in a cantilever over the ruins of Fort Thüngen, in the Dräi Eechelen Park, in the Kirchberg district, northeast of Luxembourg City. The fort was part of the defensive system that once marked Luxembourg as one of the most fortified cities in Europe.

The arrow-shaped museum building is externally superimposed on the embankment and walls of the 18th century, protecting its interior. The old walls merge with the new building, recognising and continuing the history of the place.

There are texts that try to highlight how the museum “extends its artistic influence to the outdoor areas surrounding Fort Thüngen”. They talk of “beautifully landscaped gardens, creating an inviting environment for visitors to relax and appreciate the surrounding natural beauty”.

Clearly much depended on the seasons, and our own interpretation of “natural beauty”, but above we have the view I saw when approaching the museum. I was not impressed, but accepted it for what it is. The nice thing is that the museum is set in a natural environment, which is increasingly rare these days. But an inviting “designer forest” it wasn’t!

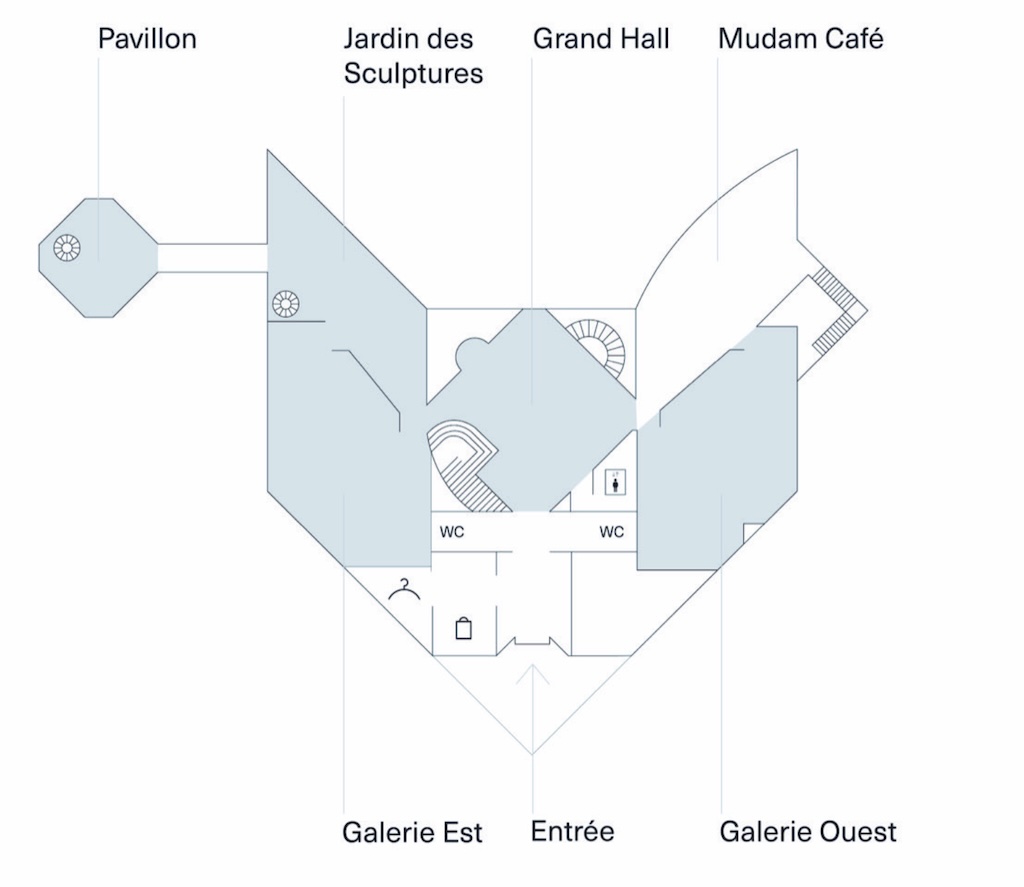

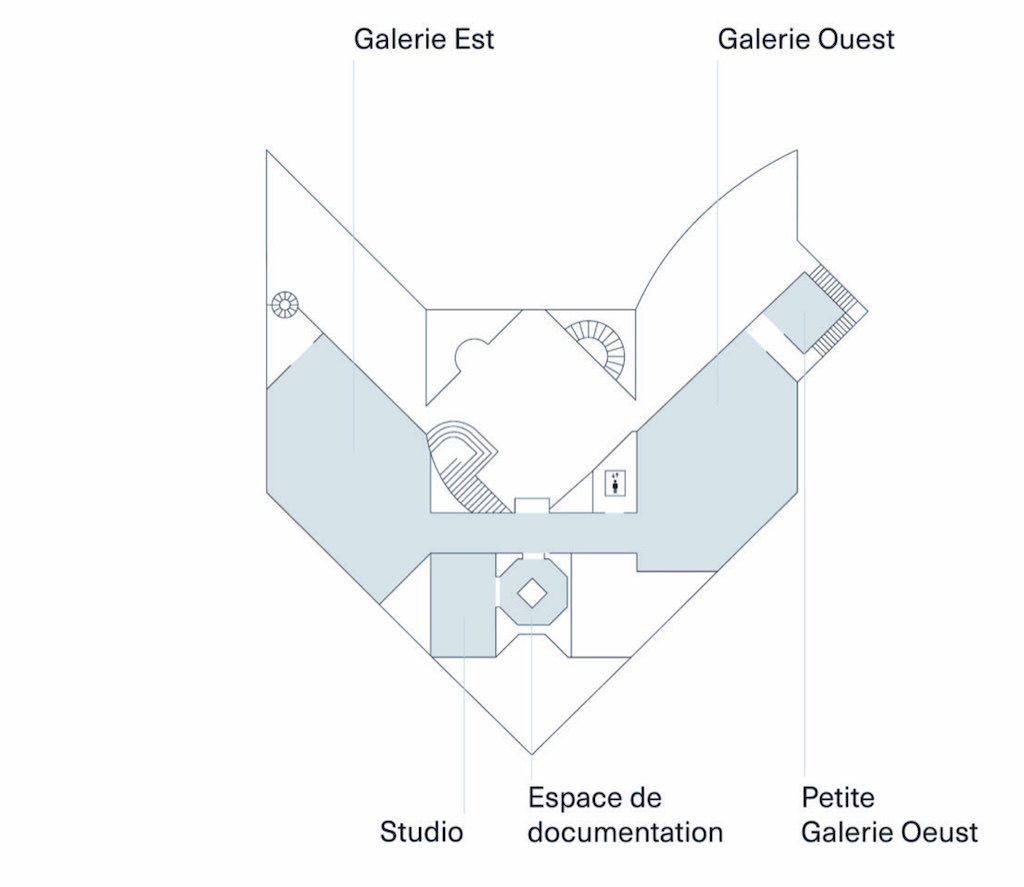

Floor Plans

The Interior

The architect visualised an arrow-shaped museum sheltered between the walls of an old fortress, a museum whose geometry was somehow an extension of it and whose interior allowed the public to move freely while enjoying a pleasant visit. I think he succeeded.

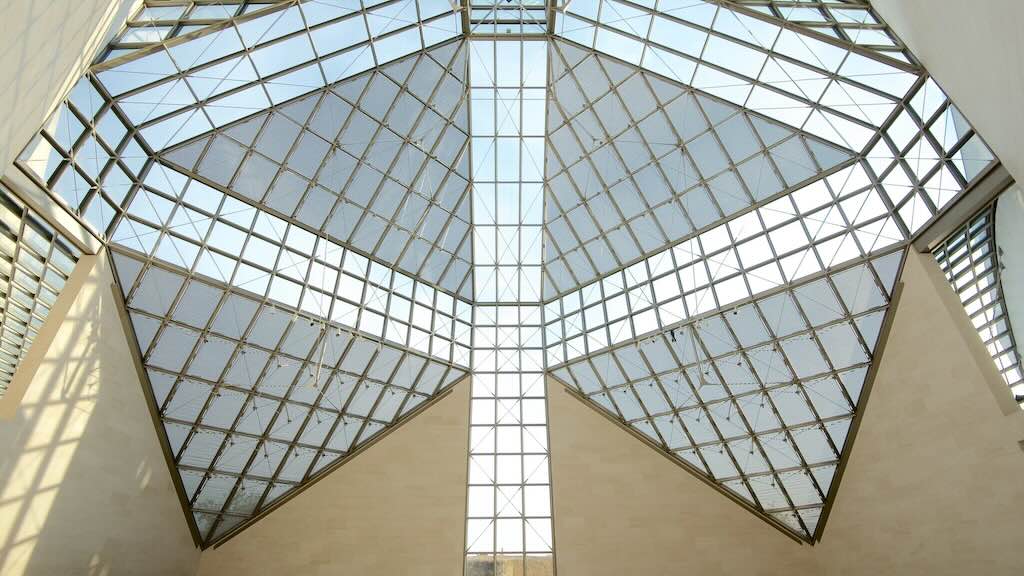

The lobby that opens to a voluminous central space, the Great Hall, a 33-metre high structure made with a metal frame topped by a bell turret with a square top.

We can see above the Great Hall being prepared for the next exhibition.

To the right of the Great Hall there is a winter garden, with its cafe.

Between Then and Now

I think almost all of the first floor was dedicated to “Between Then and Now” by Igshaan Adams (b. 1982, Cape Town), as almost a retrospective of his work.

I quote from the museum website…

Igshaan Adams’ (1982, Cape Town) practice coalesces performance, weaving, sculpture and installation. Born in Bonteheuwel, a suburb in Cape Town, South Africa, Adams draws upon his background to contest racial, sexual and religious boundaries. This intersectional topography remains visible throughout his practice and serves as a palimpsest upon which traces of personal histories are inscribed and reinscribed. Adams approaches materiality through his own subjectivity, often using cultural and religious references in conjunction with surfaces that have always been present throughout his life. His interest in material oscillates between the intuitive process of handling different substances and a formal inquiry into how various materials behave in different contexts and how they transfigure or evolve.

Between Then and Now is conceived as a woven timeline of the artist’s work, embedded with residues of history and echoes of his past. Raised in Bonteheuwel, a racially segregated suburb of Cape Town during apartheid, Adams navigated the tensions of a deeply divided society and grew up at the intersection of conflicting identities. These experiences inform his practice, which often explores the spiritual dimensions of healing and transformation.

The exhibition begins with an expansive installation of textile swatches, which visitors are invited to touch, immersing them into Adams’ studio environment. His signature tapestries and ‘cloud’ sculptures are presented alongside his dance prints, shown here for the first time as a large-scale environment. Together, they form a silent choreography that turns movement into a language of liberation.

Naturally being left handed, I turned left on the first floor and saw the tapestries and “cloud” sculptures before the textile swatches. Don’t think it made any difference.

Below we have examples of what was in one of the large display galleries on the first-floor. I must admit the distribution of descriptions around the room was not perfect. Sometimes I was not sure what the description was referring to.

This description was on the wall…

Weerhoud – ‘withheld’ in Afrikaans – is a large-scale installation composed of suspended wires and beads intertwined with found objects such as candle holders, chairs and cast-iron security bars. These materials, often second-hand and sourced from Cape Town flea markets, bear traces of personal and collective memories. The work permeates the gallery like a cloud of dust, subtle yet assertive in its presence. The notion of dust is a recurring figure in Adams’ practice. It functions as a metaphor for residue or fragment of a larger story.

The installation takes inspiration from communal rieldans – one of the oldest indigenous dances performed by the Khoisan and Nama people, In this traditional performance, the dancers quickly stomp and kick up the dry earth from the ground, fully immersing their bodies within the dust cloud that is formed. For Adams, the ephemeral movement of dust in the dance foregrounds the body’s role in shaping space and memory. The dust becomes the material trace of that gesture, acting as a physical and visual archive of the self.

I guess this refers to the cotton twine, polypropylene and polyester rope, plastic, glass, wooden and stone beads, cotton fabric, mohair, silver and nickel chain and tiger tail wire, that was hanging from the ceiling.

Courtesy of ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Aarhus, Denmark

Untitled, 2019 – with woven nylon rope, string, fabric and beads

Collection privée de Renato Ferri Pacini

I must admit that the wall panels did capture something (not sure what), and clearly represented a considerable amount of work.

Would I want to hang one in my home? No. I suspect that it says more to the person who made it, than to some alien (me) who just looks at it.

Residues of Togetherness: Athens (2024)

From the description on the wall…

Once a gardener and a painter, Adams presents his dance prints on canvas as a vibrant field of colour and gestural energy, opening a new path beyond his emblematic tapestries. These large-scale prints were created in collaboration with dancers from the Garage Dance Ensemble based in O’okiep in South Africa’s Northern Cape province. The works emerged from a workshop during which Adams rendered his installation onto an ink pad. The process involved laying down linoleum sheets and fresh paint beneath a layer of canvas. The dancers moved freely atop the surface, their movements transferring the paint to the canvas.

The chromatic layers create a dynamic rhythm, with each footprint, smear and gesture capturing an intuitive, expressive moment in time. Used as templates for tapestries, these prints function as embodied records and physical imprints of lived experience.

As Adams explains, Through movement, through dance, one is able to dislodge and release, to let go. For him, movement becomes a way to access and expel the echoes of trauma embedded in the body.

For Adams, movement and dance help to release hidden echoes of trauma stored within the body. Movement serves as a medium for healing. By recording the remnants of the dancers’ movements, this work becomes a delicate map of the past, while healing takes place in the present.