This post is first and foremost a review of a hotel, but it also looks at the country estate of a very powerful local family, the noble Golfin family.

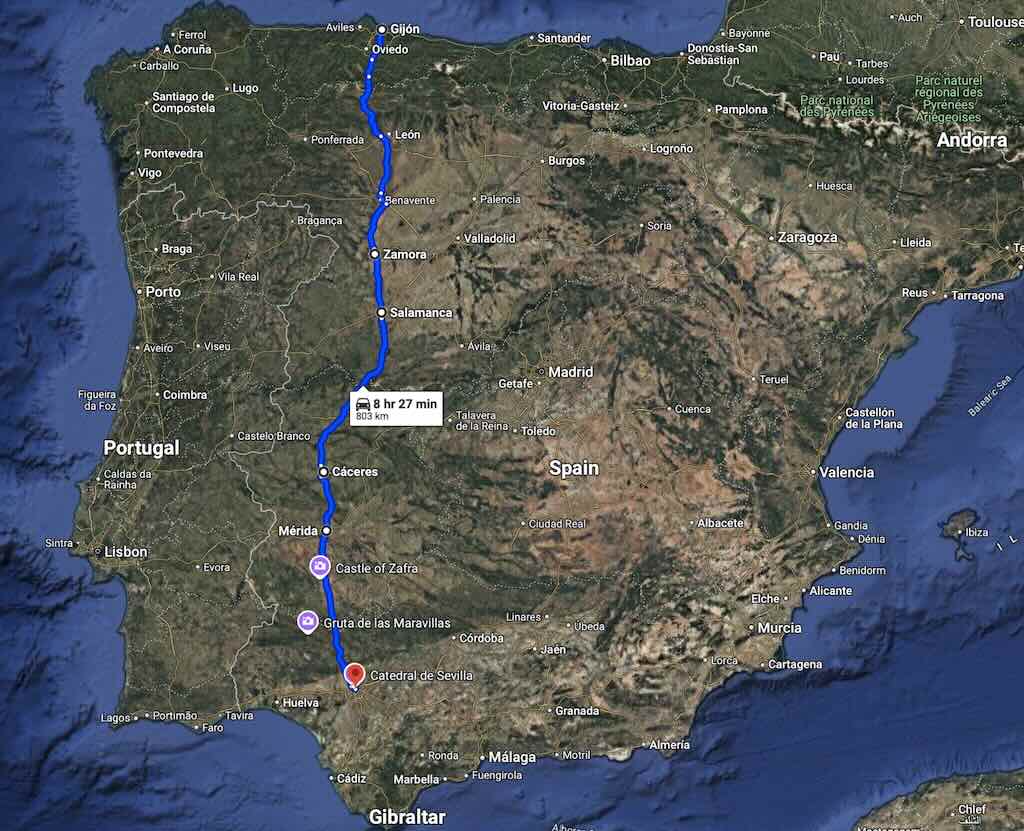

We were driving up through Spain on the Ruta de la Plata (Silver Route), which is the name given to the Spanish motorway A-66 that runs from Seville to Gijón (although we left it to continue to San Sebastián).

And we stayed 2 nights in Hospes Palacio de Arenales & Spa, very near Cáceres. This is one of nine Spanish hotels grouped under the title Hospes Hotels (a small chain run by a son of Alicia Koplowitz).

The Latin origin of hospes was simply “host” or guest”, but could just as easily be stranger or foreigner. It appears to be at the origin of hospital, hostel, hospitality, etc., or a place in which a relationship was established and developed between individuals. It certainly also took on the meaning for a place of refuge for weary or sick travellers seeking a moment of rest on life’s journey.

In fact the original Ruta de la Plata ran from Mérida to Astorga, and as Wikipedia points out the name does not derive from ‘silver’ but from an Arab word al-balat, meaning ‘cobbled paving’, and referencing an old Roman road.

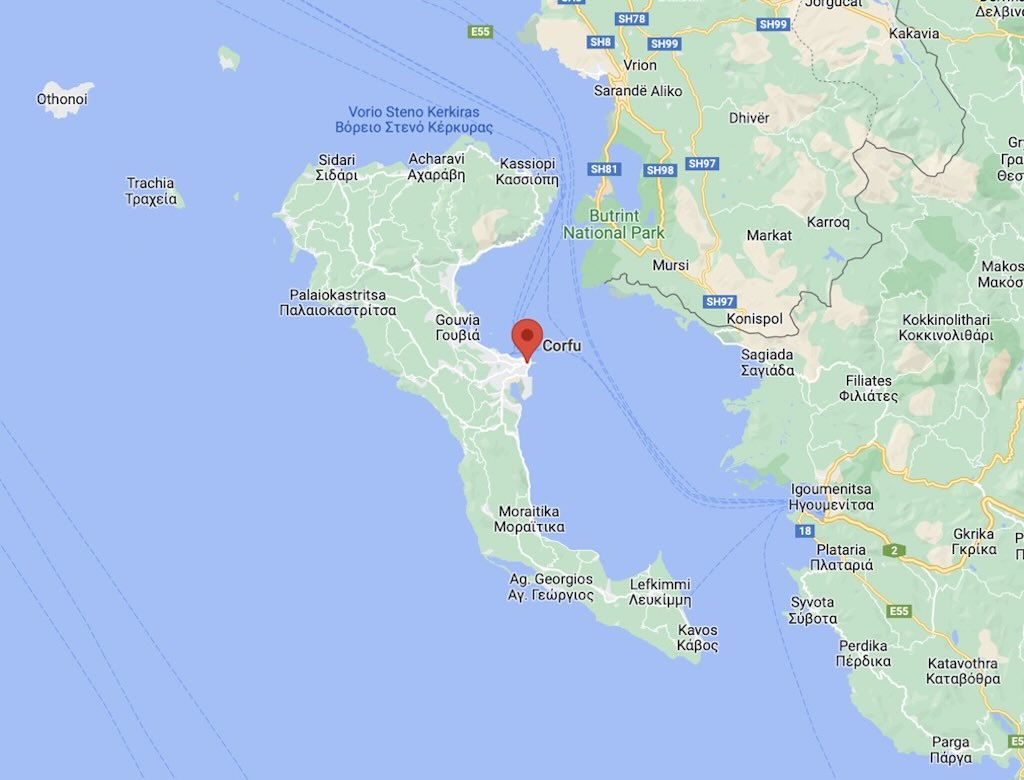

The medieval walled centre of Cáceres was declared a World Heritage Site in 1983. The municipality is in fact the largest by land area in Spain, and has the largest population in the autonomous community of Extremadura. However Cáceres is only the second largest city in Extremadura (the largest is Badajoz), and the capital of Extremadura is in fact Mérida (which has the third largest population in the region).

The name Extremadura appears to derive from the Latin Extrēma Dūriī, alluding to the fact that the province is located beyond the Douro river (modern Extremadura is not located north of the Douro). However, numerous sources mention that the name simply came from the fact that it was land outside the Moorish territories.

The hotel

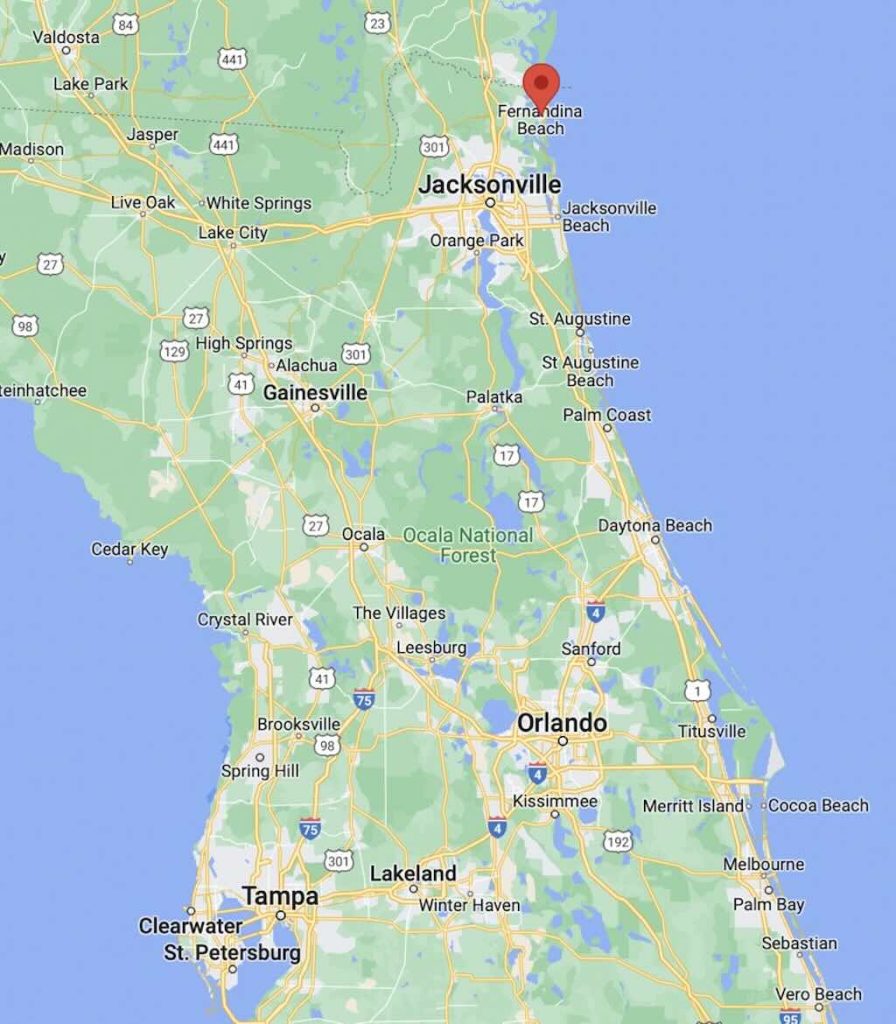

Finding a 5-star hotel in Extremadura is worth noting and visiting, and it was conveniently located on our drive north.

The hotel does not appear to claim a star-rating on its website, but there was a 5-star plaque next to the main entrance. Booking mentioned 5-stars and rated it 8.9 (Fabulous) based upon over 1,700 reviews, and Tripadvisor also mentioned 5-stars, and gave it 4.5 out of 5 (Excellent) based upon nearly 500 reviews.

As you arrive, the first entrance leads to an open car-park, which is not the most attractive view of the hotel. We arrived on a May Saturday, with nearly 30°C and the parking was full (Saturdays are very popular, above is a photograph from Sunday).

This open ‘public’ parking is actually in front of the hotel spa, which is in a separate building from the hotel itself. If you park there you will have to carry your own bags up the stairs to the main entrance of the hotel. Luckily, the parking being full, we looked for an alternative entrance, and in fact the next exit from the side road is the hotels main entrance.

The barrier was raised, so we were able to drive straight up to the main entrance.

What we see above is the entrance to the restaurant, and the hotel entrance is in the courtyard to the right. In fact this courtyard is now called Plaza de la Fuente, because today it’s home to a fountain instead of a lamppost.

Before checking-in, let’s look at the site.

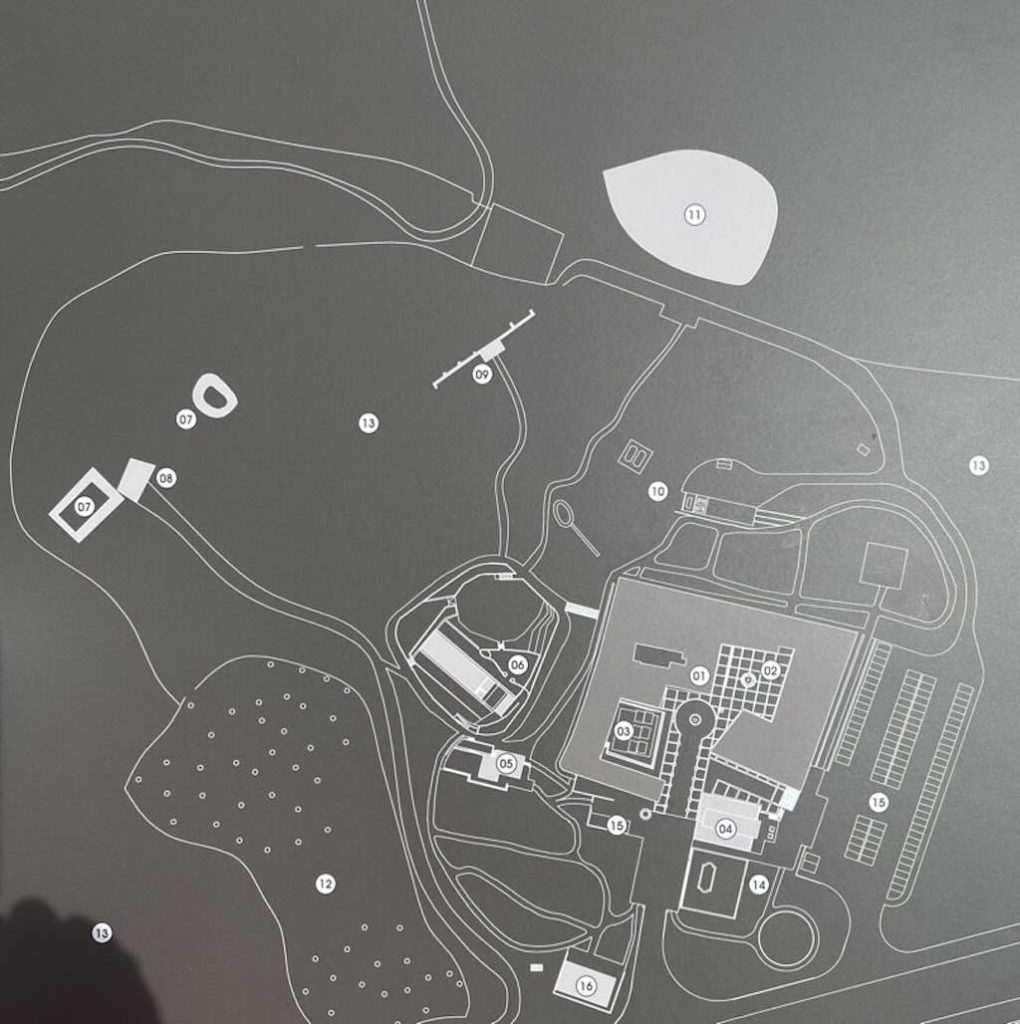

01 – Palacio de Arenales – Arenales Palace

02 – Plaza de la Fuente – Fountain Square

03 – El Pizarral – The Blackboard

04 – Spa

05 – Restaurante Atalaya – Watchtower Restaurant

06 – Piscina – Pool

07 – Cochiqueras – Pigsties

08 – Casita del Mayoral – House of Mayoral

09 – Ermita – Shrine

10 – Huerta – Orchard

11 – Humedal – Wetland

12 – Nidificación de cigüeñas – Stork nesting

13 – Olivar – Olive Grove

14 – Zona infantil – Children’s area

15 – Aparcamiento – Parking (including the underground parking)

16 – Carpa de celebraciones – Celebration tent (e.g. for weddings, etc.)

The direct translation of el pizarral is blackboard, but more generally it could be slate, or even notice-, bulletin- or score-board. Interesting, south of Cáceres, the Guadiana draws the line between Extremadura and Andalusia, and between southern Portugal and Spain. It is region where slate abounds (terreno en el que abunda la pizarra). And it is often said that “el Guadiana discurre lentamente entre los pizarrales y las dehesas de ambos lados de la frontera entre España y Portugal” (the Guadiana flows slowly through the slate groves and meadows on both sides of the border between Spain and Portugal).

Atalaya is often used to define a hotel, restaurant, etc. and in fact it means watchtower, look-out, or more or less any elevated place.

We will visit later on this webpage some of the other specific areas mentioned above, but first we need to check in…

Reception and Check-In

Check-in was easy, and they did offer to help with the bags (which we declined). We were told where the underground parking was (cost €10/night), but they did not offer to park the car, clean the windscreen, etc. The single electric car charging point (type Tesla) is in the underground garage. In addition the garage is not linked directly to the hotel, but it is closed, and you need to buzz through to the reception to open the garage door.

They showed us to our room, which was past the restaurant, down a few steps, and along a downward sloping corridor (pasillo), to our room at the end.

Our room

Staying two night, we had booked a Junior Suite with spa access. On the hotel website these are described as “two independent interconnecting spaces”, and it mentions that four of them have two floors (which they call duplex style).

We were shown one of the duplex suites. When checking in, it was obvious that my wife would have some mobility problems, she was walking with a crutch. In addition we had asked for, and the hotel had confirmed, a walk-in shower. When questioned, they said the hotel was full. In addition, on the check-in form a different room had been allocated to us, but then cancelled out.

I would have been more careful had a photograph of the ‘duplex suites’ been shown on the hotel website, and surely asking for a walk-in shower, might have triggered an additional query about mobility. Also we received several emails from the hotel, none mentioning a duplex suite.

However, my wife was able to negotiate the stairs, even if the risks were increased, particularly going down the stairs at night (the bathroom was downstairs).

So there was a sitting area, and then a wide staircase leading up to the ‘bedroom floor’. The bed was a big, very comfortable, but we are not fans of bed throws (they are useless and collect dust, and worse…). You can see on the wall a controller for the air-conditioning. This system allowed you to switch it on or off, and to raise or lower the temperature by up to 5 °C. We just switched it off.

In addition to the bed, etc. there was ‘upstairs’ also a second TV, a dressing table, and an occasional chair.

Then it was back down, to the sitting area where the wardrobe, coffee machine, and bathroom were situated.

The bathroom was large, well equipped, etc. The only comments might be that there was no window, and the glass shower wall could have been an extra 10-15 cm wide, because it was easy for my wife when using the hand shower to ‘leak’ water on to the bathroom floor.

Before moving on, I felt that for a 5-star room, it missed something. The upstairs bed area was nicely decorated and welcoming, however, the rest of the furniture was too bland and the limited window light didn’t help. I just wonder what the ‘statement piece’ below is trying to tell us,… time to leave and find somewhere more interesting perhaps?

On a practical level I would have three comments:-

Firstly, the only place to plug in things upstairs was by the bed, such a waste of a dressing table. And in the sitting area all the sockets, etc. were at floor level under the desk. So you were always on your knees plugging in and unplugging stuff.

Secondly, we had a problem with the wall safe. They had to replace the batteries, you kind of expect room-checking and routine maintenance to work better in a 5-star hotel. However, the most interesting thing is the idea that a wall safe is fixed to a wall, whereas here it wasn’t. You could lift the safe and take it with you without any problems!

Thirdly, on leaving the room, in the corridor there were a number of seats (as seen in the above photos). For most of Sunday morning each seat was covered in fresh sheets and towels waiting to be laid out in the rooms. For me, this just didn’t rhyme with 5-star comfort.

In addition, we have a pet-hate for those coat hangers that detach from the rail, using a silly hook and ring design. Given that no one is going to steal them, they could have added more than seven coat hangers.

As a final comment we ordered room service, which was delivered on the usual table with wheels, and that can be opened up to create a round dinner table. But in the main (downstairs) room there is only one chair, the second was on the upstairs balcony. There is always a risk in carrying a chair back and forth on stairs, so we ended up transferring the food and drink to the coffee table. Which, if anything, was more comfortable and less formal than sitting face-to-face at a dinning table.

Restaurant and room service

When we arrived on the Saturday at about 16:30, the restaurants were still full (as was the parking). We had received an email from the hotel telling us that “the restaurant, it is open until 23h, otherwise we have a cafeteria until midnight or if you prefer, we also offer room service”.

Now we learned that the restaurant closed at 16:00, and that the full room service menu was from the cafetería, Las Corchuelas, and only when it was open, i.e. the kitchens had closed at 16:00 and would open again at 20:00. I guess Las Corchuelas refers the Sierra de las Corchuelas which is a mountain range with pointed peaks more or less covered by the Parque Nacional Monfragüe, and situated about 40km north-east of Cáceres.

They did mention that we could snack at the pools-side coffee shop, or take room service from a limited selection of the cafetería menu (available 24h/day). We went for room service and picked Jamón Ibérico de Extremadura, a Sándwich Club, a Surtido de quesos extremeños, followed by a Semifrió de arroz con leche y crocanti de Baileys and a Mousse de tres chocolates con coulis de fresa, all washed down with a couple of beers.

My wife found the Jamón Ibérico de Extremadura a bit dry. I found the slices cut a bit thick, but I guess it’s the local habit because the same thick cut slices were available on the breakfast buffet. The Sándwich Club was slightly better than what you might find on a motorway, but just slightly. The Surtido de quesos extremeños was excellent, and came with a very tasty local jam. The Semifrió de arroz didn’t look like anything to do with rice pudding, but the Mousse de tres chocolates looked the part. However, as is often the case, the two desserts tasted the same, as did the ‘three chocolates’, as if they came out of the same packet.

The next morning we took breakfast in the main breakfast room. Breakfast had all the usual options, included egg-based options that could be ordered. I took a tortilla francesa, which is a normal omelette. I ordered it with chorizo and cheese, and it came without the chorizo. The coffee was that intense black variety that is best mixed 50-50 with hot milk. I like this type of breakfast coffee, the only problem was that the container of coffee kept running out and needed to be refilled, and the containers of hot water and hot milk were both too small and unmarked. But overall a good breakfast, with fresh orange juice, fresh cut fruit, the omelette, and strong coffee.

On the second day, early-evening, we decided to try the full room service menu, and ordered around 15:30 two Ensaladas de jamón y queso de cabra con vinagreta de yogur y mostaza, along with one helado (ice cream), and two beers.

The ensalada consisted of a bowl of green salad, covered in a layer of sliced tomatoes, a layer of (overly thick cut) jamón and a layer of cheese. Ignoring the queso de cabra which had no taste, I found the salad quite tasty, but my wife was decidedly less impressed.

The next morning we wanted to leave early, so we ordered room service breakfast. We hung the ordering slip outside our room door, and sure enough breakfast arrived the next morning at 07:30. I had asked for 2 orange juices, one fruit salad, a yogurt, toast with butter and orange marmalade, one green tea, two coffees, and some hot milk. We got two jugs of orange juice (much appreciated), two fruit salads (likewise appreciated), the yogurt, a selection of bolleterias with butter and orange marmalade (no toast, but that was fine), tea, two jugs of coffee and a jug of hot milk.

Spa

I booked a Spa for 18:00 on the Sunday of our stay. The hotel (and parking) was certainly far less crowded on Sunday. But this was not true for the Spa. When I arrived the pool was full of people, the jacuzzi full, the sauna full, and so I was left with the hammam. Surprisingly the hammam was empty, and, unusual for Spain, the temperature was set high (just the way I like it).

Conclusion

This is not a cheap hotel (in particular Saturday night), the room didn’t have the wow-factor, and the room service food was below-par for a 5-star hotel. Would we go back? Despite its limitations, we might use it again as an over-night stop, but we will certainly look at alternatives before deciding.

The country estate of the noble Golfín family

At the entrance to the hotel, there is an explanation concerning the buildings origins. It was a country estate, built in the 16th century by the noble Golfín family, and remained in the family until it was converted into a hotel in 2002. The reference of the ‘arenales‘ simply means ‘sandy areas’ (although it can also refer to quicksands and even golf bunkers).

It’s easy enough to stroll around the site and see the usual features you would expect to see, as well as a few less obvious features.

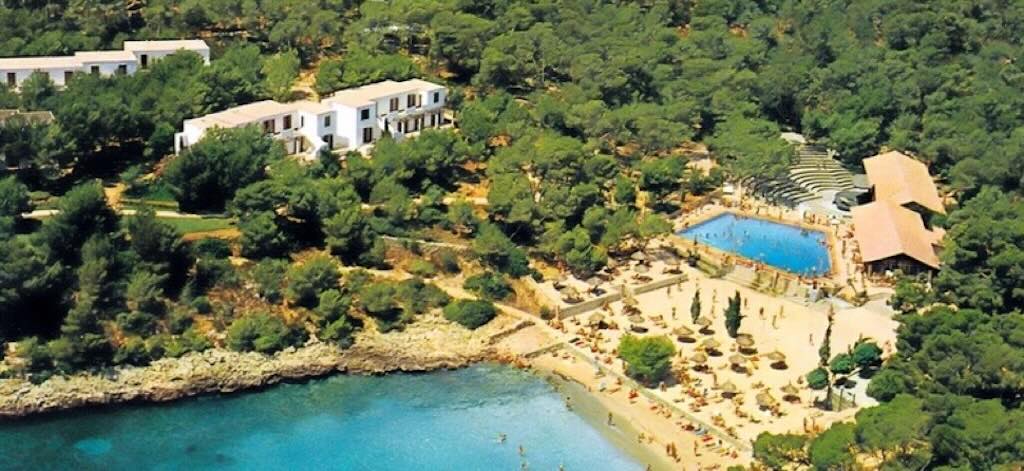

Let’s start with the obvious features. Firstly, the Restaurante Atalaya appeared closed when we were there, but the outdoor pool was fully operational with its poolside bar.

Then there was the shrine (ermita) to the Virgin de la Montaña, patron saint of the city of Cáceres since 1906.

More unusual are the Cochiqueras (two pigsties), which are 17th century enclosures for raising pigs. It is said that they were still used into the early 19th century.

Finally, the most unusual feature must be the nidificación de cigüeñas, or nesting poles for storks.

The Golfín family

We have mentioned the Golfin family, but who were they? There was a hint in the hotel, with a free entrance offered for a visit to the Palacio de los Golfines de Abajo in the historic centre of Cáceres. This site is considered one of the 10 most important historical places to visit in Extremadura, along with the Museo de Cáceres, the Concatedral de Santa María de Cáceres, and more generally the casco antiguo (old town) de Cáceres.

It was Tatiana Pérez de Guzmán el Bueno y Seebacher (1923-2012), VIII Countess of Torre Arias, who being the last of the line, established the “Fundación Tatiana Pérez de Guzmán el Bueno“. Tatiana left a fortune valued at €500 million to be managed by the foundation, a fortune including properties in Ávila, Cáceres, Córdoba and Madrid. One of the things the foundation has done is to open the Palacio de los Golfines de Abajo as a museum to show “the sobriety and elegance of the Spanish nobility that evolved over five centuries“. The palace was built between the 15th and 16th centuries. Construction began by Alfonso Golfín and was completed by his son, Sancho de Paredes Golfín, camarero to Isabel la Católica (1451-1504). The jewel of the palace is said to be its weapons room, which preserves original paintings from the 16th century. The Countess also owned 4,500 hectares of rural land around the city, including the ‘summer palace’ (country estate) now converted into the Hospes Palacio de Arenales.

This is the legend of the surname Golfín, as provided by Jesús Sierra Bolaños on his website. He suggests that the name may be of Gallic origin, or possibly of old Saxon extraction.

The more credible option is that the surname Golfín seems to come from Flanders or France, however there is no unanimity among historians who have studied the subject. It is believed that they arrived in Catalonia and from there they moved to Cáceres. Originally they were called Holken, which in French was Holquin and in Spain it was latinised in Holguin, which later producing a phonetic deviation in Golfín.

The story of Bolaños is that after the crusade against the Moors promoted by King Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1212 AD, many foreign warriors from central Europe decided to stay and settle on the peninsula. Some of these warriors, lacking a trade and without means of support, took advantage of this time of insecurity caused by the disputes over the succession to the throne, to pillage roads and steal cattle, and especially merino sheep, sowing terror over lands between the Tagus and Sierra Morena. These gentlemen, skilled in arms, became immensely rich and founded numerous strong houses, which were called ‘golfínes‘ and came to have their own king “Carchena”.

At that time, the Town Council, the main governing body of the town of Cáceres, met after morning mass, in Plaza de Santa María, at the doors of the church, where it resolved lawsuits and daily disputes in the town. It also treated matters concerning the Honourable Council of the Mesta, a very powerful organisation of ranchers at that time. They defended their members when cattle was moved through the royal lands to the pastures around Cáceres.

In one of those meetings to try to remedy the continuous pillaging of merino sheep, Mr. Gómez Tello, Mayor of Cáceres and one of the twelve Good Men who made up the Town Council, was present and said:

“Faced with so many actions by the so-called golfines, disturbing order on our roads, fields and mountains, looting and stealing the cattle of our shepherds and migratory herds, we must therefore mobilise and prosecute these crimes and with the help of the Brotherhood of the Mountains (Hermandad de los Montes) give them capture and worthy justice according to ancient custom”

However, one of the captains of the so-called golfínes, named Alfón Pérez, spied on the open meeting, and after the meeting followed Don Gómez Tello. He saw Gómez Tello speak with his daughter María, and was captivated by her beauty. The thief and highway robber continued to return frequently to the village, and through chance encounters he courted the beautiful maiden with large eyes and black hair. Little by little, love blossomed between the bandit captain and the mayor’s daughter. Until one day Maria confesses to her father, “Father, it is a joy for me to give you the news that I am in love, but I feel sadness for you because that young gentleman is called Alfón Pérez”.

The father, realising he was a golfín, went into a rage, and replied “My daughter, I forbid you to see this golfín again, that man you say you love is a thief and a ruffian and he only seeks your downfall, your dishonour”.

The bandit captain promised María that he would never give up on her, and showed up one morning at the mayor’s house ready to ask for her beloved’s hand. “Before you I present myself with my hands open and my heart as the only weapon, I hope not to offend or overwhelm you by my audacity, especially when I come sincerely and pure to ask you for the hand of your daughter, and if you did not give her to me, dead or imprisoned, I have to lie down, God willing”.

Faced with such an unpredictable event, Gómez Tello, as a sensible person and out of love for his daughter María, although believing that the bandit would not comply, he blurted out “I give you my consent and blessing to court my daughter, but first you must clear your name, recognise authority and ennoble your blood, earning the respect of the king, the nobility and the people. For this, she has my prestige and social rank, and once those requirements have been met, you will become part of my family through said betrothal”.

So the story goes, the captain of bandits became Alfón Pérez Golfín, a respected man, an honourable fighter who won for his courage on the battlefield many titles and goods.

Don Alfón Pérez Golfín, the first Golfín from Cáceres, and Doña María Gómez Tello married in the town of Cáceres, established their residence on the former home of the Gómez Tello family, today the Palacio de los Golfines de Abajo, and had several children, thus beginning one of the most illustrious lineages of the Cáceres nobility.

Experts have suggested that there is no documentation that supports this legend.

It would appear that Spanish kings would grant favours to those who made war on the Golfínes. Based on this, Alfonso X the Wise (1221-1284) granted certain privileges to the Order of Calatrava (an order that would be strongly related to the House of Guzmán). With the same condition, Sancho IV the Brave (1258-1295) authorised a certain Fernán Pérez de Bati, a knight of Plasencia (Cáceres), to build, with thirty vassals, strong houses to defend themselves against the Golfínes and wage war on them. Kings continued to grant privileges on the condition that war was waged on the Golfínes. In 1293 Sancho IV stated “that they should not be afraid of the damages that the shepherds inflicted on the Golfínes when they passed by with their cattle”. The old chronicles also record that the Golfínes were powerful and had castles and strong houses throughout the region.

One record makes it clear that that at one time golfín was the equivalent of thief or highwayman, as in rustler and cattle thief, and medieval legislation equated the golfínes with the Castilian malandrín (miscreant) and the Aragonese malsín (unhealthy, evil). All agree that the golfínes were a social plague of those times, against which cities armed themselves, and created brotherhoods (hermandades) and council militias (milicias concejiles). There are strong suggestions that the Golfín’s of Cáceres, were in the beginning if not bandits, still acquired power in the region through violence and fear. What appears equally true is that the Alfonso X did reward the family, granting them the local pastures of Torres Arias in Madrid.

There are also two documents related to pasture concessions made by Alfonso X and Sancho IV in favour of Alfón Pérez Golfín and his son, his namesake. They were respectively, Torre Arias and Fuente de la Higuera in 1261, and to his son the Casa Corchada, in 1291. However, some experts see these documents as 16th century fakes, useful for justifying the family possessions. The problem is that the original form of land ownership came from an initial distribution by the king to settlers (a form of repartimientos), and the books justifying that distribution no longer exist. Purchase and inheritance came later, but already in 1289 estates were being bought and sold. What was distributed were properties, farm land for crops, but not the resources to exploit them. Grasslands remained subject to communal usufruct rights, but cattle ranching was on private property.

By the first half of the 14th century powerful families emerged holding well defended estates and pastures. Initially (ca. 1300) land dedicated to livestock could be passed from father to son, but such lands were simply defined by paths, streams, geographical features or the allusions to surrounding vegetation. It looks as if some people had land for cultivation whilst others had pastures for livestock grazing, but there would have also been vacant spaces left for collective exploitation. By 1341, some local mayors demanded that residents show what pastures they held and what was the legal basis. Most of the letters from kings concerned land dedicated to cattle raising, but often the terminology used was confusing, but it was usually possible to deduce the exploration rights, e.g. usufruct rights or private property. One family declared that they had rights to enjoy 1,320 houses, estates, pastures, orchards and meadows, and it is thought that to acquire such assets must have involved purchases made from small owners disposing of their assets.

There was the additional problem that some grasslands had to be shared with foreigners during the winter season (often justified by contradictory privileges). It was the Mesta that defended the right to exploit pastures, and fought against grazing rights of foreigners. The way forward was to change the rules of land ownership, only allowing grassland grazing to owners of land. This essentially sanctioned the privatisation of pastures, leaving mountains, streams, and cattle routes (entry and exist paths) as common rights. From as early as 1279 there were protests logged with kings complaining about the intrusion of foreign cattle on to local grazing pastures, but the real conflicts started to increase in the 16th century, when fencing became common.

It’s noted that in the Cáceres region, conflicts were limited because from the 13th century communal and private meadows were well defined. This did not stop boundaries being abused, and conflicts occurring about grazing and watering of cattle. This was particular true in places distant from towns and villages, whereas in population centres, land occupation was higher, and residents exercised more effectively their usufruct rights. In the case of Cáceres there were complaints about people usurping land using fake support documents, or in some cases the simple justification that the settlers had occupied the land peacefully for a ‘long time’. It was equally true that those living in small hamlets found it difficult to oppose urban gentlemen (caballeros urbanos) taking over communal land. At the time the king confirmed the communal nature of the grazing land, but did nothing to stop those gentlemen from Cáceres doing as they wished. It did not help that local and municipal councils were usually controlled by those who had usurped the most land.

One might have expected the Catholic Monarchs (los Reyes Católicos) to do more to protect ordinary people, and they did order town mayors to investigate cases where knights, aldermen, etc. had usurped common land. But few actions were actually recorded. According to the testimonies found, land usurpations were detected throughout the 14th, 15th and early 16th centuries. Although the documentation is sporadic, it looks as if usurping local land was not anecdotal, but rather a constant policy carried out by the big families that often occupied positions as aldermen in the local councils. By the 16th century the usurped lands were being leased to others, who then sublet the farms to landless men.

So Cáceres defended the exercise of communal rights when they were threatened by people outside the community, but favoured the violation of those rights by residents of the town. This attitude of the council clearly supported the control of power by local knights, based largely on the expansion of their privately owned pasture space. That ownership allowed them to participate in the benefits derived from the livestock development of the Castilian kingdom, but they did so by renting out land rather than as livestock owners themselves. This is how the important families in Cáceres came to own vast estates of grazing land, that had once been communal land.

Setting aside legendary origins and looking to what is documented with certainty since the 14th century, the Golfínes definitely gained considerable power thanks to the charismatic figure of Sancho de Paredes, camarero (waiter) of Isabel la Católica (1451-1504). Sancho de Paredes belonged to the illustrious family of the Golfínes, as he was the son of Alonso Golfín, an outstanding member of Cáceres life and a loyal servant of the Catholic Monarchs (Isabel and Fernando stayed with them when they were visiting the town). The last name Paredes came from his mother and was the result of a deception. His father, Alonso Golfín, married Mencía de Tapia, daughter of the Trujillo gentleman Sancho de Paredes. He promised to make Mencía’s son heir, and for this reason they gave him the name of Sancho and the surname of Paredes, in honour of his maternal grandfather. But he remarried again, and from this marriage the famous Diego García de Paredes was born, whom Cervantes called the Hercules and Samson of Spain.

Sancho de Paredes Golfín was first a councillor of Cáceres and later, through his father, he entered the service of the Catholic Monarchs. His closeness to the monarchs, his fidelity and his great qualities made them notice him and entrust him with positions of responsibility. Thus, in 1498 he was appointed lieutenant of waiters (“teniente de camarero“), and later he was given the tenure of several castles with the task to administering justice for them. Yet later he was the personal waiter to Isabel la Católica and was one of those who signed as witness her famous last testament, where he appeared as Sancho de Paredes.

With the death of Isabel la Católica, her husband Fernando el Católico was forced to raise and educate alone the future Ferdinand I (1503-1564). Golfín was also appointed waiter for the infante, and later senior butler (mayordomo mayor). In the same way, almost all Golfín’s sons and daughters were raised as pages and ladies of Isabel la Católica. In particular she left endowments to the Golfín’s daughters, ensuring for them good marriages.

What is also certain is that there are more than fifty examples of the Golfín shields that appear on buildings, tombs, tombstones or altarpieces. In addition the Golfín family possessed two palaces in Cáceres, and the name is mentioned on tombs and in the lauds in both Concatedral de Santa María de Cáceres and the local Monasterio de San Francisco el Real (indicating a real patronage at the time of building, i.e. 15th century). There are even suggestions that some signs and writings were made by Sánchez de Paredes Golfín, and date to ca. 1530.

One event that occurred between 1743 and 1744 highlights the well-founded history of the Golfín family in Cáceres. It was a lawsuit between Don García Golfín y Carvajal and the Prioress of the nuns of the convent of Santa María de Jesús (la Priora de las monjas del convento de Santa María de Jesús). The convent was located next to the main house of Golfín, between the house and the Church of Santa María. The different buildings were separated by Callejón de Jesús and from and Calle del Rey (callejón means alley whereas calle means street). These streets and what was once the convent are today included in what is now called the Provincial Council Palace (palacio de la diputación provincial). The convent was founded around the middle of the 15th century, but was so poor that they could only build a chapel three meters wide. At the end of the 15th century Alonso Golfín agreed with the prioress to reform the church, and also agreed to exercise patronage over the chapel to be built (i.e. they were to be buried there). The work was paid by Don Alonso Golfín, and started in 1493. As far as I understand things, part of Calle del Rey was included, as was a house that the nuns owned adjoining Alonso Golfín’s house. The works was finished in 1503 or 1504, with emblazoned shields placed in the family chapels, and the altarpiece stamped with the same coats of arms. In fact the family coat of arms appeared on the vaults, the interior arches and even the exterior façade. The patronage of the the Golfín family was clear and evident.

In 1743 the nuns decided to replace the altarpiece originally paid for by Don Alonso Golfín. A nun in the convent was willing to pay for a new altarpiece on which the coat of arms of Bartolomé Xerez would appear. Don García Golfín y Carvajal opposed it, bringing a lawsuit, whereas the nuns denied the patronage. Mr. García Golfín, presented so much well-documented evidence that they could not fail to recognised the right of the Golfín family. However, in 1870 in order to build the Provincial Council Palace, the church and the convent were demolished. The Golfines remains were discarded, and all the shields from the altarpiece and walls were ripped off. However, the arms and lineage of the family can still be seen in the Palacio de los Golfines de Abajo.

Through the 18th century, different local families merged, bringing together stately homes scattered throughout the province of Cáceres, Castilla la Vieja and Andalusia, which made it possible for them to rise to titled nobility. The Counts of Torre Arias and Marquises of Santa Marta, at the dawn of the 19th century became one of the richest families in Extremadura. However, the last Golfín died in Madrid in 1829, and her only daughter (María de los Dolores de Salabert y Arteaga) took her immense wealth to her marriage with Don Ildefonso Pérez de Guzmán el Bueno y Gordon. They were the great-grandparents of Doña Tatiana Pérez de Guzmán el Bueno y Seebacher (1923-2012), legatee of all this lineage.