Contact with Daniel Christanens

In publishing this post on the Château des Vigiers, I was contacted by Daniel Christanens (daniel.rl.christiaens@wanadoo.fr), who has regularly published in the Revue de l’Agenais, of the Société Académique d’Agen.

Mr. Christanens honoured me with his contact, and mentioned that his interests often led him to see old family documents that were not in the official archives. And he was trying to give them a “virtual presence” through his publications.

His knowledge went much deeper into the local history surrounding not only this chateau, but more generally the region of Agen. I was just a casual passer-by, but I’m sure he would welcome contact with anyone who wanted to delver deeper into the history of the region.

Introduction

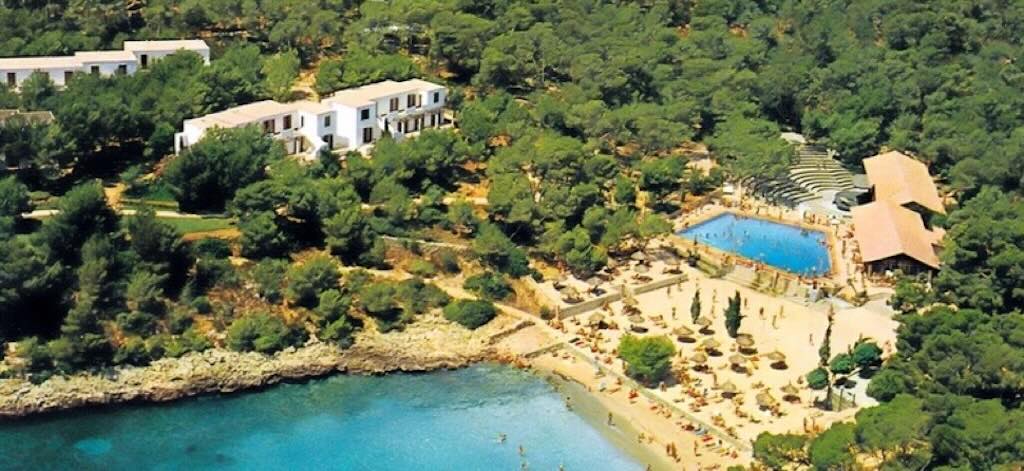

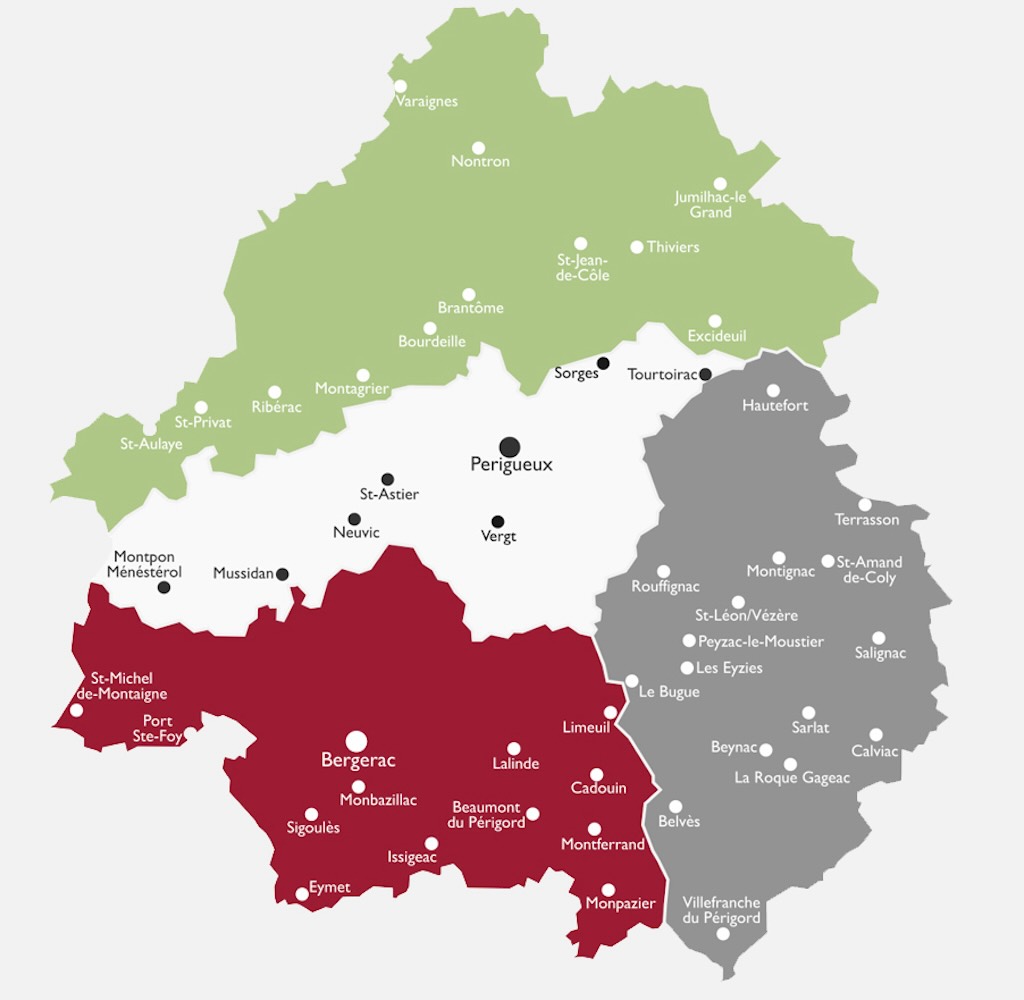

As we were travelling through France, we stopped in the secluded 150 hectare 4-star Château des Vigiers, situated in what is called the Périgord Pourpre. The château is near the village of Monestier, which is about 20 km south-west of Bergerac, or about 80 km directly east of Bordeaux.

The Périgord has been divided into four regions, pourpre (purple) named after the colour of the vine leaf in autumn, noir (black) named after the dark shade created by the chêne vert (Quercus ilex), blanc (white) named after the calcaire blanc (white limestone found in the region), and vert (green) names after the regions forests.

The hotels consists of 25 rooms in the fully restored 16th century château, and 40 rooms in a separate modern building called Le Relais. In addition there is a Donald Steel 27-hole golf course, an outdoor pool, a beauty treatment centre, sauna, steam room and gym.

There are two restaurants, the 1-star Michelin “Les Fresques“, and a brasserie “Le Chai“, and in addition there is a bar called “le 19“.

It would appear that they have now launched the Résidences de la Vallée, with 1, 2 and 3 bedroom detached houses for sale.

A bit of history

I’ve collected some information on the château from the usual blurb available, and in italics I’ve tried to fill in a few more details where possible.

It was Jean Vigiers, Royal Judge of Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, who bought the land from the Duchess of La Rochefoucauld (Dame de Saussignac), and built a château on it between 1597 and 1621.

Since the Middle Ages (10th to 15th centuries), the French kingdom was parcelled out into thousands of distinct jurisdictions and courts of varying size and influence. This chaotic situation was inherited directly from the Middle Ages where the King was theoretically the only source of judicial authority in his kingdom, but a multitude of “seigneurs” held the right to maintain a tribunal and nominate local judges. This was a right that they commonly and lawfully gained from the crown in the Middle Ages largely because it was impossible for the King to mete out justice in person.

The “justice seigneuriale“, therefore, belonged to those seigneurs that owned a distinct territory, but was attached to the territory and not the person. There were three levels of seigneurial justice, “basse, moyenne, et haute justice”, all with different competencies and usually based on the nature and resulting fine of the prejudice as well as the social status of the litigants. Seigneurs with the right of “haute justice”, for instance, had the right to judge criminal cases and to set up gallows on their territory.

Jurisdiction could vary greatly from one village to another, and seigneurial courts continued to proliferated across France during the early modern period (ca. 1500-1800). There could have been as many as 30,000 courts, most of them located in rural areas. Seigneurial justice was the most popular legal tool for litigation over property, inheritance and debt repayments, but many people considered it slow, costly and general ineffective. During the Carolingian Dynasty (613-1124) the Viguerie was the seat of criminal and civil justice. As feudal power declined the Viguerie became the lowest court of Royal jurisdiction. I wonder about the name Vigier because a Viguier was the name given in Southern France to someone who administered justice on behalf of the King, e.g. House of Capet (987-1328). So does Vigier originally derive from Viguier?

Now if we jump forward to the period 1597 and 1621, where we find a Jean du Vigier (?-1634) who was a écuyer (squire), sieur d’Ossi, seigneur (Lord) de Bessé and du Moustier, baron of Saint-Laurent. An écuyer, or squire, was a gentilhomme or anobli, so of noble birth or ennobled by the King. Originally a squire would carry the écu (shield) for a chevalier (knight), and in this period it was still seen as a honourable title. In fact écuyer or noble could be used to signify as belonging to the nobility in official documents, and someone illicitly using either title could be fined 2,000 livres. Sieur is at the origin of mon sieur (my lord), and from the 13th century sieur was reserved for “men of quality” and monsieur for non-nobles. There was also a subtile difference between sieur and seigneur. A seigneur held a seigneury, a fief or lands to which was attached seigneurial rights such as the right of justice. Normally a seigneur would have been vassal to a suzerain (a seigneur holding a fief, or even the King of France). A sieur owned land, but not seigneurial rights. Those who possessed the seigneury of a place (“de” or “du”) meant that they held the totality of the seigneurial rights of that place (otherwise they would simply be named “seigneur à …” meaning that they shared the seigneury with others). The title of baron was associated with a type of fief called a baronnie, which traditionally dated back to those who held fiefs received directly from the King.

It is also noted that Jean du Vigier was adviser to the King, on the appointment of Henri IV (1553-1610), in “la chambre de l’Edit à Agen”. Usually the role of “conseiller du roi” was better defined, either as “conseiller du roi en son conseil” or “conseiller du roi en sa cour de …” for those members of the judiciary institutions. When simply expressed as “conseiller du roi” it meant a public prosecutor. “La chambre de l’Edit à Agen” was in the 16th century a court composed of an equal number of protestant and catholic magistrates sitting on judgement of cases involving protestants (these were often called “chambre mi-parties”). This court was linked to the ambiguous status granted protestants (e.g. Huguenots) by the edict of Nantes in 1598, and the desire to ensure peace and social order by offering them special treatment.

Jean du Vigier was the son of Frémont du Vigier, écuyer, sieur du Moustier, Ministre du Saint-Evanglie, and Antoinette de Cladech. He had one brother Jean Jacques du Vigier (?-1689) chevalier, baron de Saint-Martin, and “conseiller du roi au parlement de Bordeaux”.

Jean du Vigier married Léa Gombault in 1611, and it is known that she died before 1624. They had two children Jean du Vigier and Marguerite du Vigier (ca. 1620-?). Jean du Vigier, the older, then married again to Louise de Lafont, who had also been married before and already had two children, a son and a daughter. With Jean du Vigier she would have one child, Louise du Vigier.

It is very probable that in the past a fortified castle stood on the present site of the château. Today, the round tower to the north-east, which appears much older than the rest of the building, may date from the 12th century.

The blurb from the château tells us that the architectural style chosen by Jean Vigier recalled the classic trend of the time. The nickname “Petit Versailles” has been given to it because of its similarities to one of the pavilions of the Palace of Versailles.

It may seen very presumptuous to call Château des Vigiers a “Petit Versailles” given that in the period 1597-1621 the Palace of Versailles did not exist. It was Louis XIII who had a game reserve created in 1623, where he decided to also build a simple hunting lodge with gardens near a windmill and a miller’s house. It was master mason Nicolas Huau who constructed a single body 25 meters long and 6 meters wide, with the King’s apartments on the first floor. The King’s travelling companions were lodged in the roof. Two wings were attached for the services, on the right the kitchens and the concierge’s accommodation, and on the left the store rooms and the latrines. There would have been numerous outbuildings for staff, horses, etc. The courtyard was closed by a wall with a portal carved with the royal arms. Around the building there was terracing and a stone-faced ditch (moat) with a drawbridge. It was only in 1661 that the King decided to transform the hunting pavillon in to a modest château. At this point the building would have lost any resemblance to the Château des Vigiers, and to my knowledge there are no buildings on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles that resemble the Château des Vigiers.

The Church of Sainte-Croix, located to the south of the château, dates from the 12th century, and it contains catacombs and a tunnel that would have led to the château.

I presume that they are writing about the church that is in the hamlet called Sainte-Croix, about 1 km from the château. I would be interested to know why someone might need a 1 km tunnel to link the local church with the château.

The blurb tells us that the most beautiful building on the property is the 17th century dovecote. It was the daughter of Jean Vigier, Marguerite, who took advantage of the absence of the Lord of Saussignac to order its construction without prior authorisation. On his return, the Lord, very displeased, took the matter to justice. Fortunately, Marguerite won her case and the dovecote remained intact.

Marguerite du Vigier was born in 1620 and was the second child of Jean du Vigier and Léa Gombault. In 1640 she married François de Gervain, sieur du Ralle, seigneur de Roquepiquet, and they would have three children. It is said that François de Gervain (1610-1692) died at the age of 82, and lived in Vigiers, Saussignac.

In French a dovecote is “pigeonnier” or “colombier”, the second name comes from the original Roman “colombarium”. Some could be small additions to a tower or separate outbuilding, or built into a roof apex, but others could be free-standing circular, square and occasionally octagonal stone structures. In the Château des Vigiers we can see that it was a substantial construction built outside the moat and walls of the château. Dovecotes were built as a way to breed pigeons for their meat and eggs, but equally pigeons produced an excellent fertiliser. However, pigeons wrought havoc among the crops in the region, in particular during seeding.

In France the right to erect and maintain a colombier was rigidly restricted, and was the exclusive right of three different types of land owner, i.e. “grand justiciers” (essentially a lord judge), “seigneurs de fief” (land held by a noble or lord), and “seigneurs de censive” (someone who had given homage to a lord and who was paying a rent for the land he occupied). As I understand things this only applied to a “colombier à pied”, that is a substantial building with foundations firmly planted in the ground and with nests covering the interior of the walls from floor to roof. It did not apply to the smaller wooden structures that might be attached to walls or set in gable-ends. From the blurb of the château we learnt that Marguerite Vigier was taken to court by the local lord, but she won her case. However, we don’t know on what grounds she won.

We can see that Marguerite had had built an unusual large six-sided stone colombier “sur piliers” (on pillars). These structures were held to be exempt from the regulation, and in particular if the land owned was in excess of a certain size (usually > 25 hectares) and that the colombier was placed in the centre of that land, so that the owner’s crops would feel first the pinch. In the design we see today there is a narrow central access pillar, and the lower storey might have been left as an open shed, or closed in as a fowl house. In the main body of the colombier there would usually have been a rotating ladder giving access to the different nests.

As you might imagine such a rich source of food will have attracted all sorts of vermin and pests. The first step would be to prepare the pillars and walls with a fine smooth stone and flat joints. In addition in the pillars a “larmier” (so-called hood mounding) or overhang would make it almost impossible for rats, etc. to climb the walls. We can see a second “larmier” set into the body of the colombier. In addition these “larmier” were normally specially shaped and made of a hard and very smooth stone, making it almost impossible for claws to find a grip. It’s not clear in the photograph but the entry points in the roof were often set so as not to be exposed to the strong local winds.

The blurb tells us that the Château des Vigiers belonged to the Vigier family until the French Revolution. Then, many owners followed one another until it was bought to be converted into a hotel and golf course.

The modern-day story is that in 1989, whilst on holiday in the area from Sweden, Elisabeth and Lars Urban Petersson fell in love with the Périgord region and purchased a property, destined to become their second home, near Mussidan (or Lèches). In their house search they had visited the Château des Vigiers, which was at the time a domaine viticole et horticole (wine and horticultural estate). The domain was too big for a second home, but with two friends they bought the château, and then attracted other investors to inject $12 million to create an up market country estate with a hotel and golf course. In 1991 they called upon a certain Bernard Pétine, who over the years expanded the château from a 25-room hotel to a country club style location with golf course, spa, restaurants and 80 rooms (he was succeeded by Niels Koetsier in 2017). Donald Steel, an architect of natural-style golf courses, was chosen to create the golf course, and the first 18-holes opened in 1992 (an additional 9-holes was added in 2008). The château was transformed into a 4-star hotel with 25 rooms and opened its doors in May 1993. Lars Urban Petersson, the founder, died in 2004 after a long illness.

In 2017 it was reported that the total investment had been €30 million, but it was now employing the equivalent of 62 people full time, and had an annual turnover of €5 million before tax.

They have also added a wine estate of 16.5 hectares, producing 100,000 bottles of Bergerac and Saussignac. The report also mentioned that the golf represented 40% of the turnover, and that they commercialised 12,000 nights annually, but only 7 months were profitable. Another report mentioned that the main investor had changed in 2017-18, and an addition €3 million had been invested in a beauty centre, spa and indoor pool in order to attract off-peak visitors.

Arriving at the château

We drove up from Spain and arrived in mid-afternoon. We used the postcode, and then just followed the signs to Golf des Vigiers. We past the dovecote but you can’t actually drive up to the entrance of the château.

We checked in at the main building, and were shown to our room which was also in the main building of the château.

Then we were left to bring our own bags up to the room and then park the car under the trees on the right. I found that the château entrance just lacked that wow factor.

We stopped at the terrace bar called “le 19“, but were told that they did not serve anything to eat, only drinks. Which was a real shame since the view over the lake and golf course could have been a perfect backdrop to a cold beer and a small snack.

We moved over to the terrace of the brasserie “Le Chai” where we were told that they did not serve snacks only full dishes, so we ended up ordering a croque monsieur which arrived with a salad and chips. It was a shame that there was no snacking option available, even if the croque monsieur was very tasty.

COVID rules and restrictions

All the usual restrictions appeared to be applied, e.g. social distancing, masks, hand sanitisers, etc., but there was no attempt to underline their importance. There was some COVID-related information in the room, but we were not informed about what the rules might be in the public areas, and tables on the terraces looked to be distributed as per normal.

The room

The hotel noted that 12 of its rooms were located in the châteaux main building, and that they measured between 30 and 40 square metres. In addition they “are individually decorated in a distinctive French country house style, complemented by period furniture and adorned with objets d’art”. In fact on the web you can find some impressive photographs of their rooms, however our room lacked the wow factor.

Our room was more quaint cottage than château, but I must say that it had been perfectly restored and appointed as such. Setting aside the lack of the wow factor, the room was very comfortable. However there were a couple of negative points. Firstly we had asked for a shower, but they had informed us that we would have had to move to a room in the Relais. So we decided to stay in the château, and use the shower in the bath. The bathroom was perfectly appointed, and there was a separate WC with it’s own handbasin. However the bath itself was quite narrow, and raised slightly above the floor level. This meant that my wife had some difficulty getting in and out of the bath, whilst for me it did not represent a problem. However, in the bath she had plenty of room, whereas for me it was very narrow. And we both don’t like plastic shower curtains.

The other factual criticism would be that the wall safe was too small, and would not take my iPad and portable computers. And the wi-fi was quite variable depending on where you were in the room.

Evening meal

The hotel had kindly booked a table for us at 20:15 in the brasserie “Le Chai“, but we were able to change it to 19:00 and take in the evening sun on the comfortable terrace.

My wife took the “tranche de salmon fumée, avocat et pommes vertes“, and I took the “terrine de foie gras compotée d’oignons et pruneaux au vin rouge“. We both decided to stick with two starters, and we both took for our second course a “velouté de cèpes perlé à l’huile de noix, tartine de foie gras“. My wife finished off with an ice cream and I took a café gourmand.

A very nice meal, sitting on a very nice terrace, all delivered with a friendly service. What more can you ask for!

The brasserie also had an interesting 3-course set menu for €36, which changed every day.

Breakfast

The weather was just perfect, so breakfast was served on the château terrace. Again very enjoyable, and a nice way to start the next leg of our trip.

Conclusion

We only stayed for one night during a trip out of Spain and through France, so we did not try out the golf course, pool and spa, or the 1-star Michelin restaurant.

There are two aspects to our conclusions. Firstly, we should have gone for the shower in a room in the Relais, because we found the arrangement of bath-shower a bit impractical, and the room did not have a wow factor that compensated for the narrow bathtub. The problem is that the Relais is a bit further away from both the château and the brasserie, and the breakfast has been criticised by other visitors. The reality is that the room we had, setting aside the issue of the bath-shower, was perfectly prepared and totally suitable, but didn’t have the wow factor. Both dinner on the terrace of the brasserie, and breakfast on the terrace of the château were very pleasant.

The second part of my conclusion is to project ourselves into a off-season visit, when taking breakfast on the château terrace might not be an option. Booking a room with a shower in the Relais would mean having to walk outside to get to the brasserie or the spa area. In addition the château then just becomes a place to pickup and drop-off your keys. So an off-season visit to Château des Vigiers looks like a less attractive option than this visit made in the summer 2021.

The total cost of our stay was €285 for the room, and another €196.40 for the food, etc., for a total of €481.40. The château did provide me a voucher for €50 to €75 for a future visit.

However the cost of visit was the same as the cost of our previous nights stay in the 5-star Hotel Marqués de Riscal in Spain, which had the wow factor with bells on!

Would we stay in the Château des Vigiers again? I would not definitively rule it out, but I suspect, and sincerely hope, that better alternatives exist in the region, and I would not exclude stopping in Bordeaux as an alternative. What is sure is that I would not make a detour to stay at this hotel, and I would avoid an off-season stay.

During July 2021 we stayed in five different hotels, some reservations made directly with the hotel and some through a booking agency. I’m not sure if it is a post-COVID characteristic, but my impression is that they now send out more contact emails than in the past.

We booked this hotel with Booking, but not using their app. Naturally we received an email confirming our booking, which had included a couple of additional requests concerning the room and parking. Nine day after our booking, and 10 days before our visit we received (via Booking) first an email confirming the king-sized bed, and secondly another email confirming the parking and informing us that the room we had booked had a bath, but we could change to a different room with a separate shower. In fact, we received two copies of each of these emails. The château phoned us and then, 8 days before our visit, sent us an email confirming our room for €285, with breakfast costing an additional €26 each. Two days later we received via Booking a “préparation de votre arrivée à l’hôtel” with a questionnaire. At the same time we received another email via Booking repeating the previous email about the parking and the lack of a shower in the room we had booked. And in addition this email also included a copy of the questionnaire email we had received 15 minutes earlier. Later that day we received directly from the château a thank-you for answering the questionnaire. Two days before our arrival we received directly from the château an email with the exact details on how to find the hotel. On the day we left we received from Booking a “Few hours left in Monestier?” email. The day after our visit we received an email from Booking asking us to rate our visit, and a day later we received an email from the château asking us to rate our visit. Four days after a visit we received again an email from Booking asking us to rate our visit. So that’s a total of 14 emails, excluding my replies.