Our visit was for just one night in late November 2018. I must say that at the moment of our visit the château was not as ‘manicured’ as seen above. The central gardens had lost their hedges and looked like they had been the recent home to a herd of sheep. But this in no way detracted from a pleasant stay in a nice room, topped with an excellent dinner.

Even a simple overnight stay can inspire a visitor to ask numerous questions. Firstly, what about the history of the château? Secondly, what about the history of the village, Clessé? Who was behind all this? What about the region le vignoble du Mâconnaise, and more specifically the Viré-Clessé?

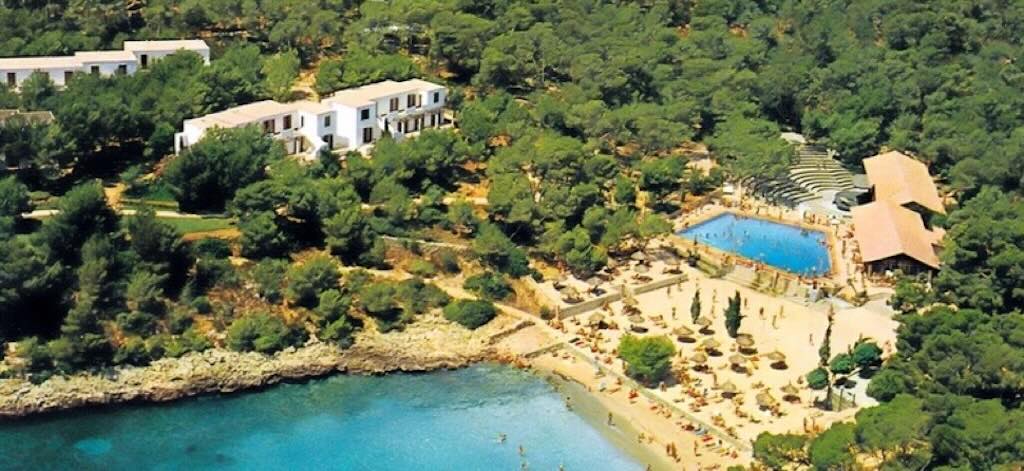

Château de Besseuil, Clessé

The Château de Besseuil in its present form probably dates from ca. 1657. It is situated in the village of Clessé in the region of Saône-et-Loire.

Below we can see the château and its out-buildings surrounding a central courtyard. We can see the restored château, home to a large period sitting room and a small number of suites. The date of 1657 is carved into the convex entablature on the period chimney.

Looking at the site we can see to the left and right of the main entrance a series of ‘out-buildings’. On each side there are a few modern style bedrooms, and on the ground floor of the left-hand building there is the modern style reception, bar and restaurant.

The food was excellent in both quality and presentation.

The modernist style continued in the bedrooms placed to the left and right of the central courtyard.

One of the key ‘selling points’ for us was the secure parking. Frankly I would not have been convinced by the parking area in front of the main entrance, however we found inside the gates a covered parking under the roof of the out-building on the right-hand side of the main entrance.

Viré-Clessé

Perhaps we can better understand the present village of Clessé through an understanding of the white wine called Viré-Clessé. But what is Viré-Clessé?

The château, and the village of Clessé, is surrounded by vines. As they say, growing grapes and making wine is in their DNA.

But let’s start at the beginning. We are in the region of Bourgogne (Burgundy), one of the main wine producing areas of France (60% of the surface area of Bourgogne is devoted to agriculture). Wine has always been part of the cultural heritage of the region. For example, the Cretère de Vix is a vase for wine dating from ca. 510 BC. And not just any vase, since it can hold 1,100 litres of wine!

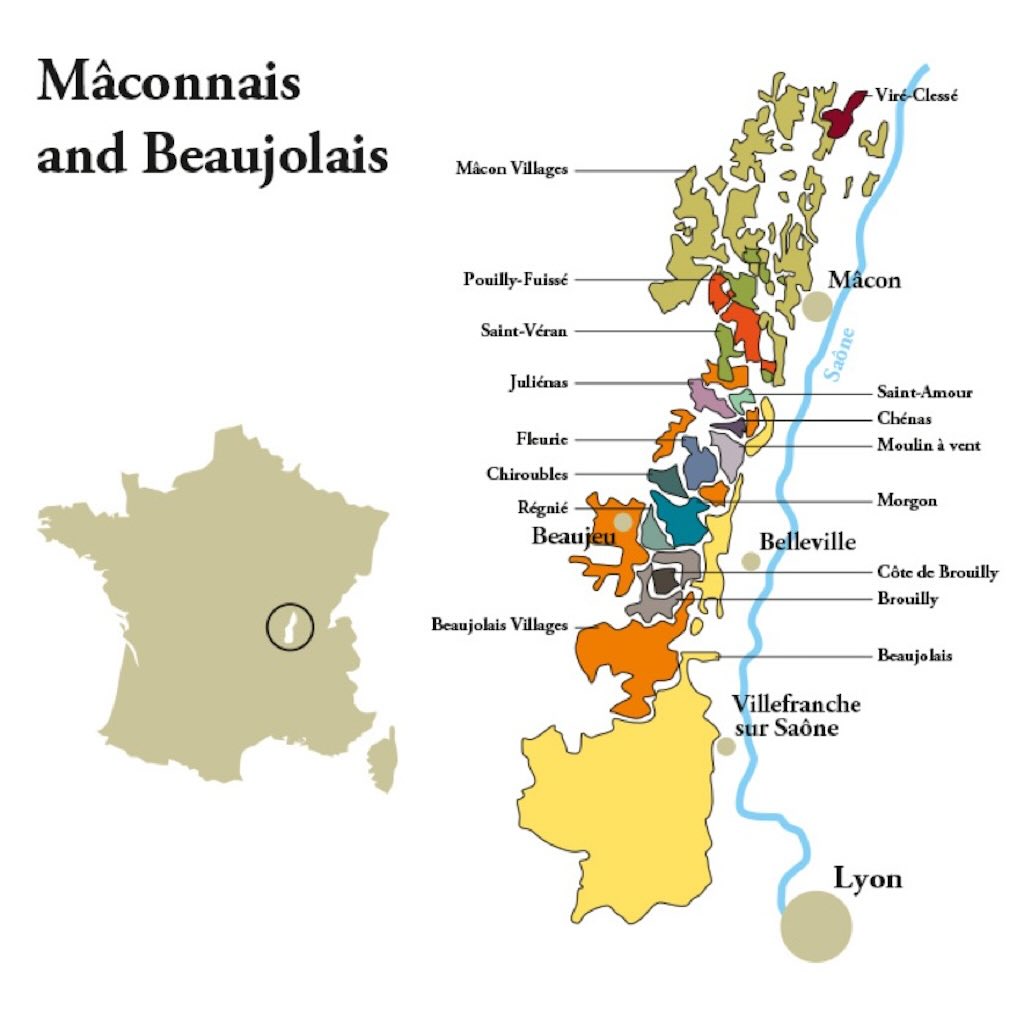

The Bourgogne is famous for its côte de Nuits, côte de Beaune, côte Chalonnaise, Mâconnais, Beaujolais and Chablisien.

In visiting Clessé we are in the area now often called Bourgogne-du-Sud, and even more precisely in the Haut-Mâconnais.

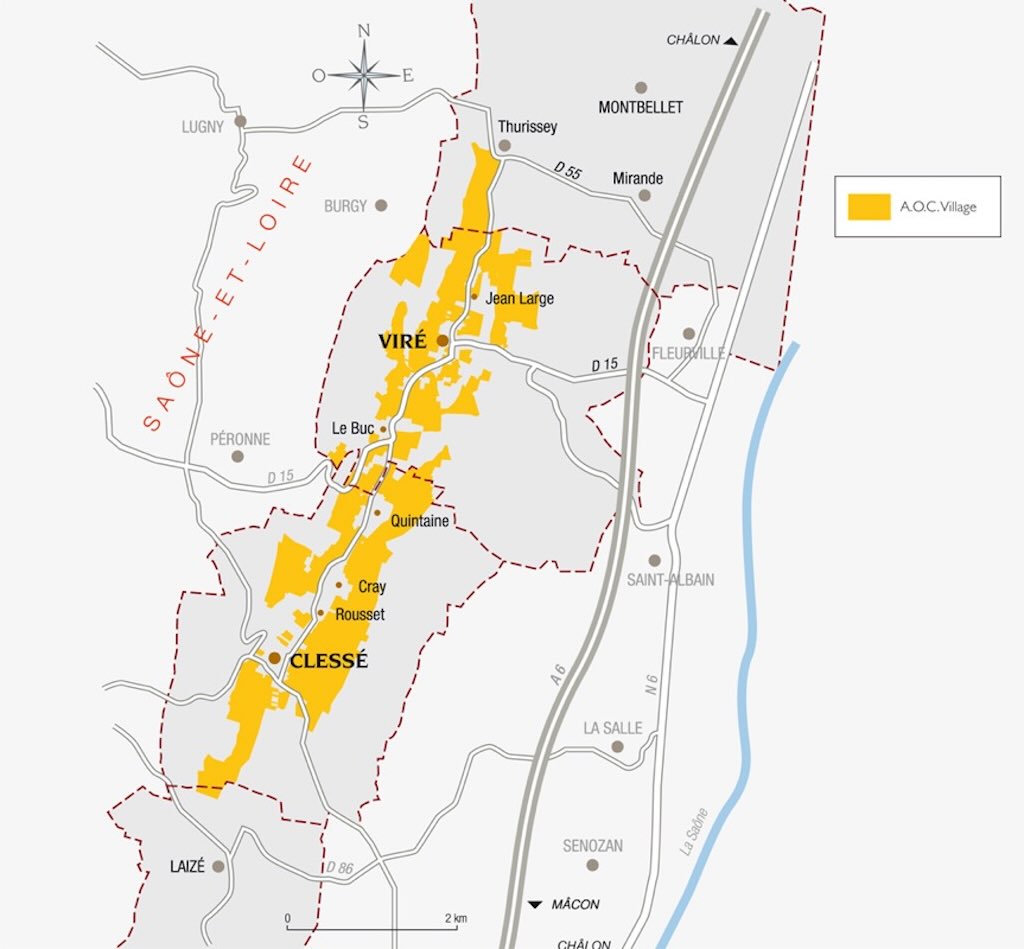

And, finally we can just see at the top of the above map a small deep red area called Viré-Classé. In fact on most maps of the Mâcon region Viré-Classé does not appear.

The reason is simple, but involves a little known fact. In the above map we can see Clessé and Viré sat right next to each other. But if we drive north another 4-5 kms, we will find a village called Chardonnay (about 200 inhabitants). In fact Chardonnay is a place, a type of grape (Chardonnay cépage or more precisely Chardonnay B), and a type of wine sold all over the world. Tradition has it that the village is the birthplace of the Chardonnay but there is no proof as such. And in fact the village only became known as Chardonnay in the 18th century. What we know today is that Chardonnay is a cross between the Pinot Noir N grape and the Gouais B. As such, today Chardonnay is now seen as a shared heritage of all the vinegrowing villages in the region.

Mâcon is best known for a variety of white wines made from the Chardonnay grape, and this grape represents about 70% of the regions production. However they do also grow Gamay and Pinot Noir and make red and rosé Mâcon wines as well.

The Chardonnay grape is grown all over the world from California to New Zealand, but it is certainly best known as the grape used for Chablis and Champagne.

The villages of Clessé and Viré have always produced wines under the Mâcon, Bourgogne and Mâcon-Villages appellations, as well as Mâcon-Viré and Mâcon-Clessé. Under these appellations there were no ‘named plots’, or Premier Cru “climat”. In both villages, and more generally in the region, wine production was concentrated in the mid-1920’s in a winemaking cooperative movement.

Because Mâcon-Viré and Mâcon-Clessé closely resembled each other it was decided to replace them in 1998 with a single appellation called Viré-Clessé (the original two appellations were abandoned in 2002). Production remains in the local cooperative, but it is also permitted in around 50 independent vinegrowers-winemakers using traditional methods as well as the so-called ‘biodynamic‘ viticulture techniques. As such Viré-Clessé is the only communal appellation in the Haut-Mâconnais.

What does this mean in practice? There is now a place for both types of wine producers in the region. The ‘cave coopérative‘ groups together more than a 100 vinegrowers covering a wide geographic area. They use traditional winemaking techniques coupled with a vatroom equipped with temperature regulated stainless steel vats able to make white, red and rosé AOC wines. They are able to allocate a part of their production to mature in oak barrels make a ‘top of the range’ wine.

Other individual producers might prefer to adopt a totally different approach. This could involve shallow ploughing between the vines to try to optimise the micro-organic life in the soil. The idea is to avoid synthetic fertilisers. Leaf-thinning and harvesting could be done by hand. Each plot could be vinified in separate temperature controlled vats with a natural fermentation and no yeast seeding. This permits producers to focus on more complex white wines and to allow the red’s a longer vatting giving them more structural characteristics of the local ‘terroir‘. Some small producers claim that their production is totally organic, untouched by chemical fertilisers, herbicides, or pesticides. Yet other producers focus on avoiding chaptalisation and only using native yeasting. Some producers delve into the world of agroforestry, mixing vines, orchards, and hedges.

We can close this little visit to the Viré-Clessé wine by noting that the Château de Besseuil also has 3 hectares dedicated to Viré-Clessé.

Early History

Many of our more ‘profound’ questions can be answered by looking at the early history of the village.

According to Wikipedia, the area around Clessé was certainly inhabited by a prehistoric man related to the Solutrean industry, an advance flint tool-maker from around 20,000-15,000 BC. It has been said that the region provided an excellent type of silex used by tool-makers of the period, and still today worked silex chips are occasionally found by local wine producers.

Wikipedia goes on to note that there are a few megaliths (e.g. menhir or ‘standing stones’) that might be associated with the druids from pre-Roman times. In fact there is a large megalith in Clessé which has a series of 9 notches cut into its surface. Interpretations vary from a Neolithic polishing stone to a druid ceremonial stone (the first suggestion is more likely). Pagan artefacts integrated into early Roman buildings could suggest that the region was originally occupied by earlier Celtic peoples.

Wikipedia stresses that we are certain that Clessé derives from the latin ‘Classiacus‘, which itself will have derived from the first owner of the region, ‘Classius‘. There is an additional reference suggesting ‘Classius‘ built a villa at a place called Rousset, and his name was later carried over to the small hamlet. We are talking about the so-called Gallo-Roman period, the Romanised culture of Gaul that occurred in the 3rd C to 5th C AD. There is mention of the importance of Roman roads and Wikipedia notes that there are remnants of a Roman road in Clessé at a place called ‘les Justices‘.

We can perhaps delve a little deeper into the history of this Roman road. We have already noted that Clessé is situated about 15 km from Mâcon, which itself is situated about 65 km north of Lyon. Already in 27 BC Lyon, known then as Colonia Copia Lugdunum, was the capital of the province of the Gaule Lyonnaise (Gallia Lugdunensis) and the seat of the Caput Galliarum, or ‘Capital of Gaul’. Lugdunum was strategically important to the Romans and was the hub of a network of Roman roads collectively called Via Agrippa. Experts suggest that originally this network was built for military purposes (viae militaries), but later also became an administrative and civil network as well (viae publicae, consulares and praetoriae). One of these roads went north to the Rhine River and Germany, and as was normal practice this road would connect to a network of secondary roads, some paved and some left unpaved. As far I understand it one of these secondary roads connected Autun to Mâcon, and passed through Clessé. As mentioned above some the paving stones are still visible in Clessé in a place called ‘les Justices’. Some texts suggest that this road was just a ‘viae compendium’ or connecting roadway, but the roads construction might suggest otherwise. It was about 5½ metre wide, consisting of blocks, pounded layers of dirt, and large paving stones, all lined with flagstones standing on edge. There are suggestions that some of these ‘secondary’ roads followed the crests of the hills and provided a fast alternative to taking a longer route on the main road. In fact many experts believe that these secondary routes were built over older Gallo-Roman routes or even earlier Celtic routes.

There is a strong suggestion that the Roman road that passed through Clessé was damaged during the invasion (or migration) of the Germanic tribes (ca. 300-500 AD). We know that the region hosted the Burgondes in the 5th century, but they did not mix with the local population. Each applied their customs and laws until the fall of the Burgondes capital Autun to the Méeovingiens in 534 AD. It would appear that the road through Clessé was later restored and became known as the ‘Chemin de Brunehaut’ (via ‘Brunichildis’), presumably after the Frankish Queen Brunehaut (ca. 547-613).

One interesting comment mentioned that the Roman road Mâcon-Autun crossed the route between the Jura and the Atlantic coast (Mediolanum Santonum) that was used by monks from Baume Abbey and the Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Gigny who founded the Abbey of Cluny.

A partial inventory of historic buildings in the Saône-et-Loire region shows that there is a unique concentration of Roman style constructions. Buildings in the region are almost impossible to identify until the 8th century (except for canalisation and sarcophagi). However we do know that artisans in the region had mastered the extraction, cutting and transport of sizeable stone blocks, and experts presume that church building would certainly have started in the 6th century. Some buildings can be dated back to the 9th century. For example, the Abbey of Charlieu dates from ca. 872 and there is a crypt in Tournus that was completed before 980. And some part of the Abbey of Cluny date to 960-980. A small inventory made in 920 mentioned a number of modest buildings in numerous places throughout the region. At this time building progressed in and around monasteries, in particular at Tournus and Cluny. It was during the period 980-1040 that Cluny extended its influence, and that the bishops of Mâcon and Chalon fought to control ecclesiastical buildings (and revenues).

At this point it is difficult to focus just on the village of Clessé, but we do know that after 534 AD the Franks mixed with the local Gallo-Roman and Burgundian nobility. According to many experts the power through the 7th century was held by the local Bishop (Évêque) and an increasingly important feudal nobility. With the Carolingian Empire (ca. 800) regional conflicts intensified, and ‘châteaux forts‘ and defensive towers became common landscape features. From about 1060 violent conflicts occurred more and more frequently between the ‘Clunisiens‘ (Cluniac movement) and the bishops and priest of Chalon and Mâcon. In fact by the 11th century the Abbey of Cluny had become the acknowledged leader of Western monasticism (by the 12th century the Abbey had nearly 10,000 monks). Throughout the 11th and 12th centuries the regional population grew, along with new villages and new areas allocated to agriculture. Into the 12th century land was increasingly concentrated in the hands of the Ducs de Bourgogne.

From 1060 the rivalry between Cluny and Chalon and Mâcon was the principle motive for building. To manifest their power and reinforce their spiritual control over the region each side extended their existing churches and monasteries, and each went for increasingly rich decoration. As an almost natural extension, the development of agriculture in the region centred on the village centre with its local church (for this reason power was increasingly concentrated around the parish church).

We know that by 1080 the bishops of Mâcon had in Clessé a seigniory with two castles, those of Chavanne and of Germolles (later sold after the French Revolution). We also know that Clessé was home to a manoir and a large farm (‘Quintaine’), whereas Viré was home to a manoir (Château de Viré-Châtillon) and a fortified church (Château de Vérizet), and Chardonnay was home to a manoir. In 1221-1241 the bishops of Mâcon built a new church, and by 1260 the imposing rectangular bell tower was integrated into the fortifications of a château-fort also belonging to the bishops of Mâcon. At this time both Clessé and Lugny (a village about 3-4 km from Clessé) were attached to the powerful ‘châtellenie‘ of Verizet in Viré, which played the role of a kind of administrative centre of the canton. Later this château-fortress would become an important royal ‘châtellenie‘ which would later be destroyed during the French Revolution (some parts of the tower, etc. are still visible but much was re-built at the end of the 19th century).

Today Clessé is proud of its church (Notre-Dame de Clessé) whose facade and octagonal bell tower are characteristic of Romanesque art in the region (some experts detect a certain ‘Clunisian inspiration’). Built in limestone at the end of the 11th century and in the first part of the 12th century, there is a decoration of Lombard arches on the gable of the facade and on the first level of the octagonal belfry. The upper level of the belfry, of later appearance, is perforated with twin bays with small columns, capitals and archivolts under Lombard arches. It is capped by a modern roof in glazed tiles.

An important question for the region concerns the first planting of vines for wine production. We know that the major Roman roads were important for the traffic of amphora of wine from Italy. The preference of the Celts was for barley beer, but there are ample records indicating that wine was also appreciated by the local population. Carbon-14 dating of raisin pips and winery equipment found in Lournand (about 12 km from Clessé) indicates that vines were planted for wine production sometime during the 2nd or 3rd centuries AD, more or less at the same time that wine importation waned.

The earliest references to wine in the region concerns private donations made to the church which mention ‘viriaco‘, the wine of Viré. Vines are mentioned in the charters of local abbeys dating from 936 and again in 987.

However it would be a mistake to think that wine production was historically a major activity in the region, or a product that brought great riches to land owners. In 1685 the value of the vine was about twice the value of same land prepared for animal feed. At that time there were only 9 presses in the region and the total production in the area around Viré and Clessé was about 600 hectolitres (equivalent to 75,000 of our modern day bottles).

From the middle of the 11th century land clearance slowed down and most useful land became agricultural. This meant that the flow of new church donations started to dry up. The whole of village life coalesced around the parish network. The churches control of the parish meant that it controlled society.

By 1240 the Cluniac “model” crushed everything else, meaning that most building was associated with additions and partial reconstructions and repairs of existing buildings. In the local region around Clessé and Viré Gothic building fashions did not flourish. Some Gothic reconstructions became bogged down, and ended with the addition of some simple decorative features.

With the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) church buildings were often abandoned or poorly maintained. It has been stated that in 1600 most of the churches in the area were in ruins or badly damaged. In the aftermath of the Wars of Religion, the dominant layers of society adopted another attitude towards the church. It became just a tool for supervising the rural masses. The clergy was transformed into a body of civil servants in the service of the French State. The bishops became no more than an instrument of monarchical power, and priests became parish registrars.

What I’ve tried to do is highlight the context against which the Château de Besseuil would have been built. We have already noted that even as far back as 1080 the bishops of Mâcon had in Clessé a seigniory. Records appear to show that this was still true in 1590, and that in 1595 a certain Antoine de l’Aubépin was Lord (‘Seigneur‘) of Clessé. Separate documents show that Antoine de l’Aubépin (or l’Aubespin) was Cantor and Canon of Cathedral Saint-Vincent (Chalon Cathedral) and Provost and Canon of the original Saint-Pierre collegiate church in Mâcon. But we also know that in 1600 the Royal bailiffs (‘bailliage‘) sold off his possession (along with the sale of wheat and wine) due to what appears to have been a lawsuit brought against the inheritance of Antoine de l’Aubépin by Jean and Aimé de Chardonnay, Lords of Saint-Lager, and the children and heirs of Humbert de Chardonnay, Lord of Épaux. There are also records that show that by ca. 1620 the estate in Clessé was leased by François de Rébé, Archdeacon in Lyon and Provost of Saint-Pierre in Mâcon.

It would appear that in 1595 a certain Pierre de Sagie married Philiberte de Viard (of a family merchants in Tournus). Pierre de Sagie was a deputy bailiff and Alderman in Mâcon. There are solid indications that they built their home in the village of Clessé. It would appear that in 1629 their daughter Claudine married a certain Archambaud Chanuet, a prosecutor in Mâcon, and after inheriting the building in Clessé they decided in 1646 to build a real château. According to records the family remained in the château until the end of the so-called ‘Ancien Régime‘ (1789). However records also show that ca. 1737 the château was substantially re-designed and finally took on its current appearance.

Looking at our hotel building, and in particular the front façade, it is possible to distinguish two or three building phases. The first phase might have been a simple stone building with a short tower on one side. A second phase might have included an extension of the building placing the tower in the centre of the façade. The third phase clearly included the extensions wings to the left and right, and a second floor and new roof. There are stylistic questions concerning the double front doors, the variety of window locations and styles, and the central stairs which are quite small and tight for a château of that size.

The château survived the French Revolution more or less intact because Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) is said to have called the Château de Besseuil a ‘petit bijou‘ (a little jewel). I have not found the original quote, and personally I found the building a pleasant example of a local ‘manoir‘, but in many ways far from being an ideal example of a noble French château.