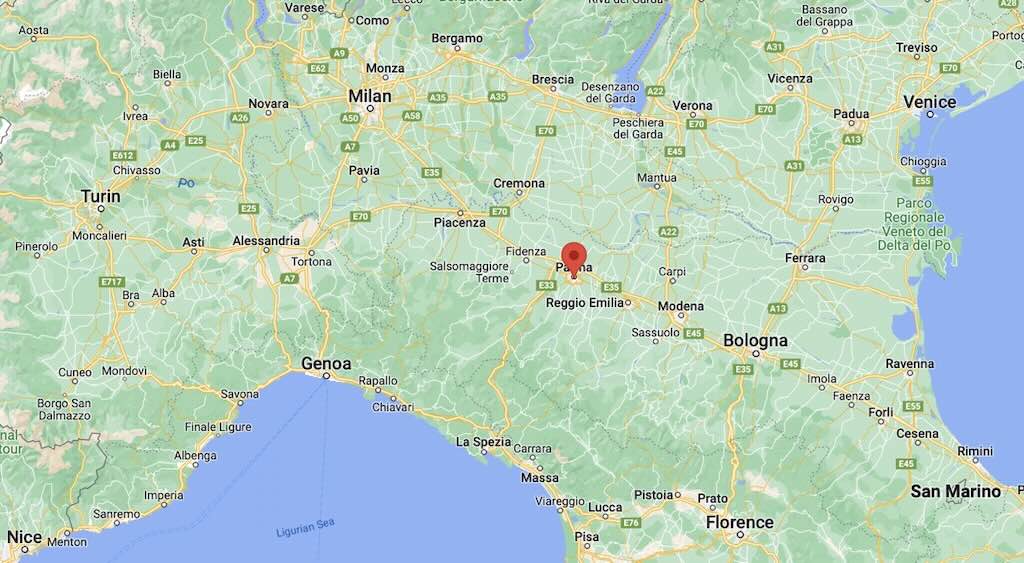

We were driving down through France, direction Spain, and we found an overnight stopover on Booking. The hotel was the Chais Monnet & Spa in the centre of Cognac, a town famous for one of the world’s best-known types of brandy, the cognac.

The reality was that we planned to stop nearer to Bordeaux, but finding a good hotel in the week before Christmas proved more difficult than I had expected. And low and behold, at the last minute we found a 5-star hotel in Cognac. This did mean taking on a longer leg to drive down to our next hotel in Elciego in Spain, but I hope you will see that it was well worth the stopover.

Our GPS had no problem finding 50 Avenue Paul Firino Martell in Cognac, but even in front of the hotel it was not immediately evident that we were in the right place.

The hotel is often presented as above, but in fact the building is not visible from Avenue Paul Firino Martell, i.e. see the hotel entrance below.

The avenue is named after Paul Firino-Martell (1885-1949), who was twice mayor of Cognac in 1929-1932 and again in 1935-1945. We drove round twice to be sure we had the right address.

Even looking through the entrance it is not obvious that we are looking at our hotel. Remembering that at the end of the road we had driven past the main buildings of Martell, one of the “big four” cognac houses, along with Hennessy, Rémy Martin and Courvoisier (they represent 93% of all cognac sales). Was this just another cognac house?

Naturally everyone will point out that the name Monnet was over the entrance gate, and there were (small) plaques on the walls telling us it was a hotel, and it was the Chais Monnet.

Fortunately a very accommodating and friendly porter was hovering around, confirmed that we were in the right place, showed us to the parking, and walked us to the reception.

What are "les chais de Cognac" and who is the "Maître de chai"?

The easiest translation is that the “chais” are the Cognac cellars, and the maître de chai is the cellar master.

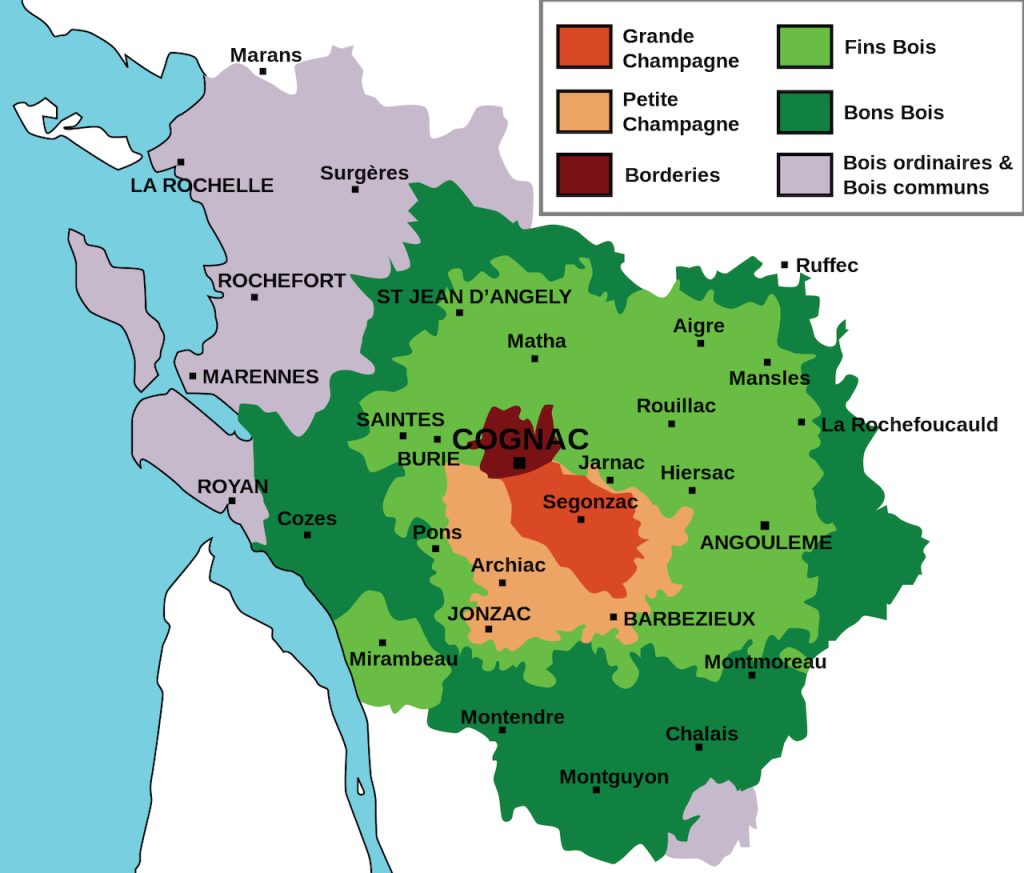

In fact the Cognac vineyard extends over three French département, Charente, Charente-Maritime, Deux-Sèvres and some communes of Dordogne, i.e. around 75,000 hectares (as a comparison the champagne vineyards cover around 34,000 hectares).

There are 6 Grands Crus of Appellation Contrôlée and delimited according to the specificities of the soils and the quality of the resulting eaux-de-vie, namely Grande Champagne, Petite Champagne, Borderies, Fins Bois, Bons Bois and Bois Ordinaires. Often you see Premier Cru de Cognac associated with Grande Champagne, but it’s not an official term, even if it does truly suggest that Grande Champagne is the finest area within the Cognac region.

Cognac is obtained from a white grape variety called Ugni blanc (better known as Trebbiano), and to a lesser degree other grape varieties such as Folle Blanche and Colombard.

‘Ugni blanc’ is the most widely planted white grape of France, and the Trebbiano family accounts for around a third of all white wine in Italy.

The ripe grapes are usually harvested in October. After pressing, the juice is then left to ferment for about three weeks. The young white wine is then distilled to make an eau-de-vie.

The basic steps today are the same as those used since the very birth of cognac.

The distillation is carried out in two heat cycles. A first passage in the still makes it possible to obtain a milky liquid called “brouillis” (raw spirit) which is then put in a boiler for a second distillation called “la bonne chauffe” (fine spirit). The first distillation cuts off the “head” and “tail” which are the most and the least volatile components. The second distillation again cuts off a “head” and “tail” leaving the “heart”.

As far as I know the distillation of cognac can only be performed in an “alambic charentais” which is made of copper and consists of a boiler, an onion-shaped head, a swan’s neck, and a condensing serpentine plunged in a water tank.

The resultant alcohol, which if anything resembles an Italian grappa, is then aged in oak barrels until it matures… sometimes for decades.

Some locals call these barrels “sleeping beauties”.

Thanks to the porosity of the wood, the eau-de-vie will be in indirect but permanent contact with the surrounding air and will gradually lose its alcoholic strength and volume. This evaporation is poetically called “la part des Anges” (the Angels share).

Also oak will modify the appearance of the cognac, giving it a characteristic amber colour. The final distillation will pass through three different oak barrels to achieve different characteristics in the final product. For the first 6–12 months it starts in a new oak barrel where it gains a lot of its spicy aromas. Next it goes into an older seasoned cask that will give the cognac more texture, suppleness and complex aromas. Finally it is aged in an old 10–20 year barrel that will add the last refining touch.

The unofficial grades used to market cognac are based on their age counts. According to the inter-professional French institution BNIC (Bureau National Interprofessionnel du Cognac), the official quality grades of cognac are the following:-

- VS (Very Special) or *** (three stars) – aged at least 2 years in oak

- VSOP (Very Special Old Pale) – aged at least 4 years in oak

- Napoleon or XO (Extra Old) – aged at least 6 years in oak.

Cognac is seeped in tradition. Some “sleeping beauties” are awakened within a few years and sold off as relatively ordinary cognacs, but a small percentage are left to sleep for much longer. Every year experts sample the barrels and set aside for immediate sale those deemed incapable of further improvement.

As the survivors from this rigorous selection process mature, so their alcoholic strength diminishes and within forty or fifty years is down from around 70% to 40%, the strength at which cognacs, old and new, are put on the market. These truly aristocratic brandies are then transferred to the glass jars (damejeannes), known to the Cognacais as bonbonnes. Each holding 25 litres and owners will store them in the innermost recesses of their own cellars, which they aptly call paradis (paradise).

Hennessy has the biggest paradis, but an even more impressive collection is hidden away in the crypt of the medieval church of the small town of Châteauneuf-sur-Charente. It is there that the Tesseron family store their brandies. For nearly a century, four generations have supplied even the most fastidious of the cognac houses with at least a proportion of the brandies they require for their finest, oldest blends. The Tesserons’ two paradis contain over 1,000 bonbonnes dating back to the early 19th century.

The world of cognac is governed by certain immutable rituals. Even when pouring the 1853, the firm’s maître de chai will swill out the empty glass with a little of the cognac to ensure that the glass is free from impurities. Despite its age, a 1853 cognac does not have the tell-tale signs of old age, for old wines are inevitably faded, brown, and their bouquet and taste at best a momentary experience. Yet a 1853 cognac was distilled when Queen Victoria was still young, and the grapes came from vines some of which had been planted before the French Revolution.

It interesting to note that cognac is known worldwide, yet today the town has only about 30,000 inhabitants, and when it first rose to fame in the 18th century it had fewer than 2,000 inhabitants.

What was the Chais Monnet?

Originally the site was a complex of industrial buildings, cellars, cooperage, manufacturing workshop, office and concierge, built between 1838 and 1848 for a Société Vinicole. Wikipedia has an unusually extensive webpage on Monnet Cognac, and I have liberally copied it across on my webpage whilst trying to add the odd additional bit of information.

In fact it was in 1838 that a certain Pierre-Antoine de Salignac, a progressively minded local aristocrat, gathered several hundred wine growers to form the Société des Propriétaires Vinicoles de Cognac (SPVC). This was a cooperative endeavour aiming at marketing their product directly to international clients and bypassing the dominant market power of established houses such as Hennessy, Martell and Otard-Dupuy. The SPVC was first established in Jarnac, and over time it attracted more than 400 winegrowers and distillers, including some important landowners. Pierre-Antoine de Salignac introduced a number of innovation, namely he started to classify cognacs by district (as they did in Bordeaux), and he also suggested to reinforce the ageing process. As a result sales increased as did prices. The company soon sold the brandy under the SPVC brand, and prospered during much of the 19th century. By 1870 it had become the second largest producer of cognac, just behind Hennessy. The brand’s emblem from inception in 1838 was a salamander.

The salamander echoed both the cognac production process (as it is reputed to survive in fire, and thus evoking the heating phase of distillation) and the local history, since the salamander was also on the arms of the royal house of Valois-Angoulême and of its most famous scion François Ier, born in Cognac in 1494.

Pierre-Antoine de Salignac died in 1845 in a horse and cart accident, but was succeeded by Georges de Salignac, and later by Louis de Salignac. Despite SPVC being led for six decades by members of the Salignac family, in 1897 the shareholders decided to dismissed them and chose as its new head Jean-Gabriel Monnet, a former employee of the rival Pellisson cognac producer. J-G. Monnet subsequently appeared as a brand alongside SPVC in 1901.

Louis de Salignac would establish his own cognac company, Louis de Salignac & Co. In 1974 they were bought by Hiram Walker, who had already bought Courvoisier in 1964. But in 1986 it moved to Allied-Lyons before being bought by Domecq in 1994 (see Allied-Domecq), which was then taken over by Pernod Ricard in 2005. Today Louis de Salignac is a subsidiary of Courvoisier, which is part of Beam Suntory Inc.

Jean-Gabriel Monnet strengthened his control of the enterprise in 1905 and transformed it into a joint-stock company in 1920. His son Jean Monnet worked for the firm in his youth before the outbreak of World War I, and again briefly in the mid-1920s after resigning from his position at the League of Nations in December 1923. In the early 1920s, Monnet had the second-largest market share in the United States behind Hennessy. In the 1950s, it became the official cognac supplier of the royal court of Sweden, while remaining one of the top 10 cognacs in the United States. Control of the company remained in the Monnet family until 1962.

In 1962, partly to finance Jean Monnet’s Action Committee for the United States of Europe, the family sold its control of Monnet Cognac to the Rhineland-based Scharlachberg winery. Robert Monnet, a cousin of Jean Monnet, continued to manage it until his death in 1971. In 1987, Scharlachberg sold Monnet Cognac to brandy producer Asbach Uralt, which in turn sold it to Hennessy in 1991. In 1992-1993, Hennessy transferred it to another of its brands, Hine, and in 2003 sold Hine (and thus also Monnet) to CL Financial, a Trinidadian and Tobagonian conglomerate that also owned spirits producer Angostura, while retaining ownership of the original production facility. In 2013, then-struggling CL Financial sold Hine and Monnet to EDV SAS, an investment vehicle of the Guerrand-Hermès family, owners of a significant stake in the Hermès luxury brand and also formerly associated with wine retailer Nicolas until its 1988 acquisition by Castel Group. Since its sale by the Monnet family, Monnet Cognac had been sold mostly outside Europe.

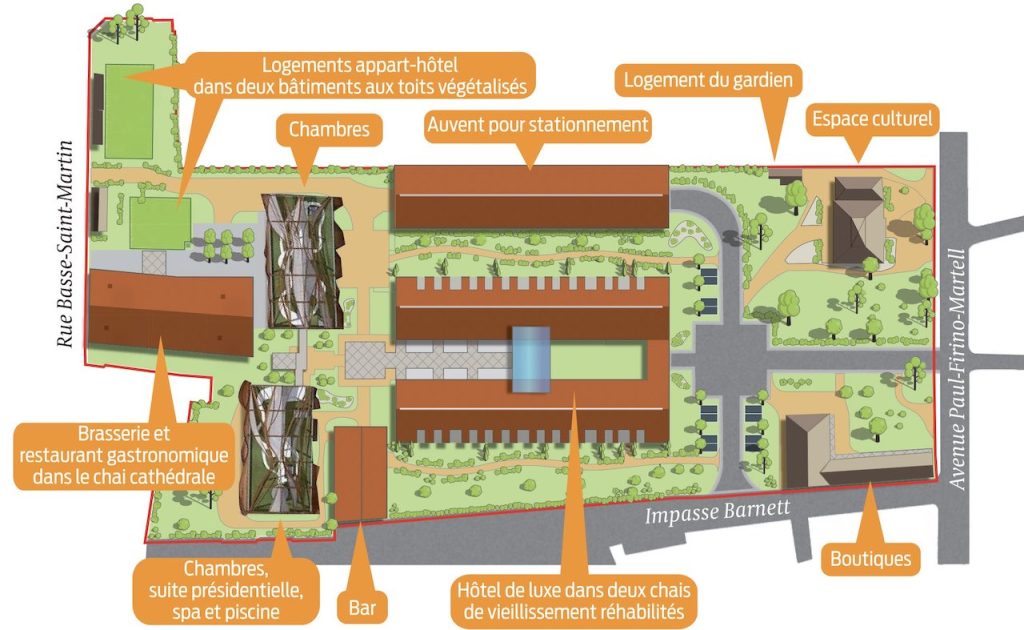

The Monnet cognac production facilities were initially built from 1838 to 1848 by the SPVC and covered more than 50,000 square meters, including the chais, cooper’s workshop, production workshop, and offices, on rue de Pons (now avenue Paul Firino Martell) in the Gâte-Bourse suburban neighbourhood of Cognac.

There were still 30 employees working there in 1986, however production stopped in 2004, and in 2006 LVMH sold it to the Cognac municipality. After a decade of neglect, British businessman Javad Marandi purchased the site in July 2016 and redeveloped it as a luxury hotel, designed by Paris-based architect Didier Poignant. The €60 million complex includes the former mansion built by the Salignacs and used by the Monnets following the 1897 management change. It now serves as a meetings’ facility of the hotel. There was also a high-ceilinged cellar known as the “chai-cathédrale“, built for 40 barrels (foudres) of 250 hectolitres each, now converted into a restaurant named Les Foudres.

Chais Monnet - first impressions

First impressions are important, and the first question is why do they present the hotel as being a modernist glass block covered in an abstract mess of rusty iron girders, when first impressions are far from avant-gardist.

We are going to walk through our arrival in the hotel, and I’m going to also try to capture a little of the work that went into restoring the site.

We drove up to the main entrance and parked just on the right, although a very large covered parking area was also available a little bit further to the right. And below we have the very classical looking entrance arch.

It might look timeless, but as seen below the “restoration” had to take the whole the site back to basics, e.g. removing all the roofing of the chais because they were built with sheets of asbestos fibre cement.

Love the ‘red carpet’.

And the bare walls became a walkway through to the hotel reception, with bedrooms on either side.

It’s perhaps the moment to have a closer look at the entire site…

We drove in from Avenue Paul Firino Martell, parked to the right of the entrance, and walked between the two chais which originally were used for ageing the cognac. It worth noting that the site itself drops more than 8 meters down to the Rue Basse Saint-Martin.

We approached the glass cube in the middle, where the lobby and reception area is located. It’s possible, hopefully probable, that the reader is now prepared to expect the unexpected…

Here we are looking back from the reception desk, and can just see the entrance to the lobby. Two points worth noting, firstly the lift with the double spiral staircase, and secondly, the restored wooden roof frames recovered from the original chais.

The restored roof frame and the double spiral staircase are gratuitous, perfectly and wonderfully gratuitous.

The lift and double spiral staircase provides access to the hotel rooms on the first floor. And just to make it that bit more difficult, I understand that they first installed the lift, and then commissioned the double spiral staircase from a different company. Naturally the walls and doors of the lift are curved, and I must admit the mechanism is not the most silent and fluid I’ve seen. You can see that each of the staircases provides access to a different landing, so you have to select the floor in the lift on the correct side so as to access the correct landing. All the more complicated because both landing provide access to the same set of rooms on the first floor – so in fact it does not matter which side you exit!

The roof trusses are wonderfully sculptural, but certainly don’t provide the structural support they once provided in the roof the chais. What is less well known is that there is something called locally torula compniacensis (le champignon noir du cognac), but which goes by the technical name baudoinia compniacensis. It is a form of fungus that lives in places were there is airborne alcohol, and is often just called “warehouse staining”. So the roof frames had to be dismounted, sand cleaned, repaired and then put back in place.

Our room

Before we get carried away with the restoration and architecture of this hotel, lets check out our room. First impressions, so important, already started in the corridor. Sometime corridors leave no lasting impression, sometimes the impression can be negative, and sometimes they can set the bar high, raising exceptions concerning the room itself. Here we had a spacious corridor, excellent colours and decoration, and even a few art pieces, albeit mass produced.

And the room did not disappoint. Spacious, warm colours, quality fittings, a certain simple elegance.

Of course the room came with the usual complimentary water, coffee machine, minibar, amenities from Fragonard, etc.

What did I particularly like?

Firstly the room was comfortable, the space, the decoration, the bed, the seating, the lighting, etc., all oozed comfort.

Secondly, I liked the shelf panelling behind the bed. It was fitted with bedside adjustable reading lights, and it was also a great place to leave stuff knowing you can find it all again. Also it’s worth noting that the art sitting on the shelf was in fact fixed to the wall.

I also appreciated the effort made to add colour and texture with the curtains, and in particular with the wonderful big curtain tassel used to open and close the curtains, plus they ran so smoothly.

I liked the switches, lighting, etc. and was impressed to find 6 USB charging points.

Separating the shower and WC was also a real positive.

What about negatives? Too few to mention? Despite the room being of a high 5-star standard, there were a few real negatives:-

- Firstly, the Internet connection was inexistent. On our first evening we were told that the technician had gone home and they could not re-establish the Internet connection. The reception did offer us access to their staff connection, but the signal in our room was too weak. The next day the hotel did re-establish the Internet connection, but it only lasted a hour or so, before failing again. The wifi signal was strong, but it would appear that the access provider was the problem. The hotel told us they could do nothing about the problem since it was with their service provider. We left the next day, and the Internet connection was still down.

- Secondly, next to the sink in the bathroom there were two sockets, marked “sockets only for electric razors”. So our electric Braun toothbrush and water jet did not work. Fine for a battery toothbrush, but the water jet needed to be connected. My wife was not happy.

- Thirdly, in the room there was a small but perfectly functional sitting area with two relaxing chairs and a small side table, but no chair for the desk.

- Fourthly, the safe was situated in a draw. It was a good sized, strongly built, top-loading Hartmann Tresore, but despite it being relatively heavy you could still simply lift it out of the draw and walk off with it. Better not leave your Crown Jewels in it.

- Lastly, the idea of a stuffed soft bed mat might be interesting, but we set them aside because they could just as easily trip up someone going to the loo at three in the morning, in the semi-dark.

There were also a few “could do better”, namely:-

- Firstly, the room art, was not particularly inspiring and/or contextually interesting. Clearly a question of personal taste, but I would have preferred some decorative items that reminded us of where we were staying. We can see above an example of the artwork in our bedroom. Fixed above the bed we could not really look at them closeup, so I’m not sure what the message was? I would mention that I appreciated more the art in the public areas of the hotel (which we will see below).

- Secondly, the TV interface was a bit clumsy. One example, was the out-of-date room service menu which was truncated by the hotel interface screen header and footer. Clearly the menu was simply a document file added to a server, it did not scale to the hotel interface, nor did it offer language alternatives. Another example was the weather forecast comparing Cognac with Tirana, Rome, Wien, Minsk, Brussels and Sofia! The ‘multimedia’ option just pointed to YouTube and Internet Radio options, and the wifi option was a joke. Also the constant screen popup about the hotels commitment to hygiene and cleanliness was pointless.

- It’s also worth mentioning that the some of the shower attachments were starting to come loose.

- Lastly, the suitcase stand was fine for our small Samsonite, but it would not be useful for a larger suitcase.

Continuing the site visit

Above we can see the two chais and the central location of the future glass lobby and reception area, where we found the circular lift and double spiral stairs. Below we can see the glass lobby, and another new glass cube, which they have called “Le Hub“. This “hub” provides a central access to the two new buildings (the ones with the abstract mess of rusty iron girders) called “Les Ceps” which provides access to more guest rooms, the spa, fitness and pool, the rooftop terrace, the ballroom and the restaurants.

As far as I could tell there was no interior route between the rooms in the chais connected to the lobby and reception area, and the two new buildings housing the pool, restaurants, etc. You have to leave the warmth of the reception lobby (remember we were in December) and walk towards “Le Hub” along a partially covered walkway (see below).

In the above photograph we are actually looking back towards that warm reception lobby, but at night I must admit the lighting does draw you towards “Le Hub” and the restaurants. However, I do wonder at the distance separating the parking area and the prestige restaurant Les Foudres, which is set even further back in the Chai Cathédrale.

Beyond “Le Hub” we (finally) can see “Les Ceps“, two glass covered building covered in an abstract mess of rusty iron girders. Here we have a new construction, built from the ground up.

They had to start by removing 30,000 cubic meters of very dense limestone rock, before finally completing the “rusty iron girder” buildings.

It’s worth noting here that I have nicknamed this building the “rusty iron girders”, but I still quite like the dramatic effect created, and I applaud both the architect and client for going down this route. I’m not 100% convinced that they add to the context of a restored distillery, nor to the history of Monnet Cognac, but bravo anyway.

I have not found a justification rationnelle for the use of these girders, but that pales into insignificance when faced with the ‘work’ (shown below) that can be found in multiple sunken pits in the area of “Les Ceps“.

I leave the reader to ponder the artistic merit of the above “work” (which I have named ‘Mess in the Middle’), and I now turn to more practical considerations…

Room service

We ordered room service at 18:50 (room service opened at 19:00), and it arrived at about 19:30, which for some people might be a bit slow. Initially we were working on the room service menu available on the room TV service, but in fact the reception gave us a paper copy of the updated room service menu.

Fortunately the new room service menu was a touch more complete, with an additional starter, an additional fish main dish, and two additional meat dishes.

The old room service menu included 8 Burgundy snails for €26, a John Dory fish dish, a veal meat dish, and a vegetarian gazpacho.

The new menu included starters, 6 huites spéciales Gillardeau N°4 (€19), truite Française en gravlax (€22), a salade croustillant de Pintade Française (€21), or (now) 12 Burgundy snails (still for €26). Fish now included filets de Rouget Grondin (€31), Cabillaud à la plancha (€36), or Homard “blue” et sa bisque (€55). Meat dishes included blanquette de veau (€29), suprême de Pintade Française (€34), tartare de boeuf (€28), or a côte de boeuf Limousine (for 2 people) at €105. Finally “all day” fish & chips (€22) was replaced by “les incontournables“, fish & chips (€25), Burger du Chais (€25), and Club Sandwich (€23).

For our first room service evening meal I took the Burger du Chais and my wife chose the blanquette de veau. I then decided on the selection of cheeses “Annick Saunier” (€13), and my wife chose two scoops of ice cream, vanilla and chocolate (€5).

I enjoyed my Burger du Chais, very tasty and the chips were nice and crunchy. I have no idea who Annick Saunier is, and the waiter could not tell me which cheese was which. My wife was not that impressed with her blanquette de veau, although I thought it was tasty enough if not that attractively presented. She thought her ice creams were average, and the meringue was too hard (probably had been left in the fridge).

For our second room service evening meal I took the fish & chips, and my wife chose the risotto aux cèpes (€26). I then decided to try the entremet chocolat, caramel salé et cacahuètes (€10), and my wife again took two scoops of ice cream, vanilla and chocolate. The four smallish pieces of fish was lightly battered and tasted perfect, but the chips were poor compared to those served the night before with the Burger du Chais. My wife’s risotto was tasty but lacked that little extra something,… truffles maybe.

However, the entremet chocolat, caramel salé et cacahuètes was fantastic, but so rich that it was perhaps a touch too much … (I never thought I would ever write that).

Next time I will just take the entremet for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and at €10 room service it is an absolute steal. I should have ordered 10 and taken them with me as we drove down through Spain.

The room service drinks menu included something called Abatilles (a type of water), the usual coffee options (including a Café Cognac), and a white or blond Atlantic beer. No wine options, probably because the minibar was stocked with half-bottles of Château Clarisse (a 2017 Puisseguin-Saint-Emilion at €39), a Sancerre Domaine Vacheron (2020 at €36), a Champagne Domaine Collet (different from that mentioned but probably priced at €45), and finally a 50ml Pineau des Charantes Château de Beaulon (€14).

On both evenings we ordered two Atlantic beers (€9), and a bottle Abatilles pétillante (€6.5). The Atlantic is from Brasserie des Gabariers, a local micro brewery. A nice beer, and an excellent initiative by the hotel.

All the prices were TTC, taxes and service inclus, and I must say for a 5-star hotel the room service prices were very competitive (in particular for my entremet chocolat).

It’s also worth mentioning that the out-of-date menu on the TV was in English, whereas the updated paper menu was in French.

Breakfast

Breakfast was served in “La Distillerie“, but we could have also ordered breakfast in the room.

I found the decor a bit cluttered and dark, but after a few drinks (it is an old distillery) I suppose it would be considered warm and friendly.

The staff at breakfast were so-so. Breakfast consisted of coffee or tea (the coffee was very good), orange juice (very good) and a small basket of pastries (see below for two people). My wife asked for some honey and she received one of the little pots, and separately some really good honey in a small jar.

It intrigued me that for room service we received lots of bread and 6 butters, but for breakfast just a few pastries and two butters.

There was also an egg-based menu, and the first morning I ordered eggs Benedict, with salmon, i.e. “Eggs Atlantic”. As seen below it was less than convincing. The muffin had become a half of a slice of white bread (toasted – you are joking), the salmon was there for presentation purposes alone, and the sauce had the unique feature of being totally tasteless (at times I though it might also be non-Newtonian).

You can probably guess, the next day we avoided the egg-based menu, which is perhaps what the staff wanted. But it makes coffee and pastries expensive at €35 each.

The pool

As with the restaurants, the pool and spa are in a separate building, requiring guests to exit the hotel building and enter a separate building (i.e. the modernist part of the site).

The pool itself is impressive and there was a separate “jacuzzi-style” area at one end, and a part of the pool extended in to the garden at the other end (covered in winter).

Through the archway there was a hamman at a reasonable temperature, and a sauna at 80°C (which was not hot enough). The hamman and sauna was a let-down compared to what is offered in many other 5-star hotels.

Things we didn't see

The Angélique Café was not open.

‘The 1838’ … with live jazz performed on weekends, was closed.

We didn’t manage to visit the gastronomic restaurant Les Foudres, set in the Chai Cathédrale. It’s a shame that we did not manage to see what looks to have been a major restoration and conversion project (still there is always next time…).

We also didn’t manage to see the roof terrace, which again we reserve for our next visit…

In passing…

Here and there, and in particular in “Le Hub” there was some additional artwork on display from a local artist Sylvain Piget.