In May 2022 we stayed at Hospes Palacio de Arenales & Spa, very near Cáceres. This hotel is part of a network of 9 Hospes Hotels, so in December 2022 we decided to try two of the other hospes.

So for our trip back down to Spain we decided to stay at Hospes Palacio de San Esteban in Salamanca, and Hospes Las Casas del Rey de Baeza in Sevilla.

The Latin origin of hospes was simply ‘host’ or ‘guest’, but could just as easily be stranger or foreigner. It appears to be at the origin of hospital, hostel, hospitality, etc., or a place in which a relationship was established and developed between individuals. It certainly also took on the meaning of a place of refuge for weary or sick travellers seeking a moment of rest on life’s journey.

Booking gave the hospes in Salamanca a 9.1 (Superb) based upon 3.096 reviews, and Tripadvisor gave it a 4.5 (Excellent), but based upon 1,092 reviews. Booking noted this hospes as a 5-star hotel, and one of only four 5-star hotels in Salamanca city.

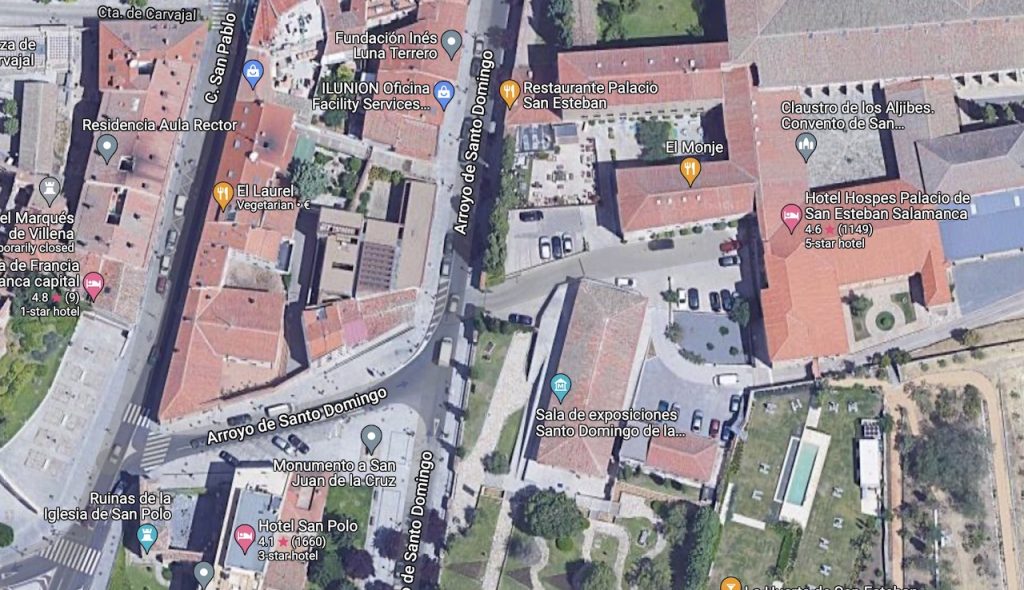

Our car GPS took us to within 50 meters of the hotel entrance, but it still took a moment because the entrance was quite discreet. We had already contacted the hotel about a secure parking and a room with a separate walk-in shower.

We arrived along the Arroyo de Santo Domingo, passed the Hotel San Polo, and more or less guessed that our hotel was just across the road.

The Hospes

The hotel staff came out immediately, as if they were waiting just for us. They took our bags, gave us each a small bottle of water, signed us in, parked the car right next to the hotel main entrance, and saw us and our bags to our room. The welcome was perfect. Later we would find out that our room on the first floor overlooked the entrance and our car parked in the forecourt.

Below we have the lobby which was decked out for Christmas. Down the stairs there was a separate entrance and a bar.

The hotel occupies a small part of the old Dominican convent of San Esteban, which claims to be a fine example of what is called Plateresco salmantino.

Above we can see the façade of the Church, and to one side the entrance to the convent (pórtico del convento). The hotel is on the right side behind the convent.

The Plateresque was an artistic movement, mainly architectural, characteristic of Spain and its territories, which emerged at the end of the 15th century, between the late Gothic and the Renaissance.

For example, in Salamanca the most famous examples are La Casa de las Conchas with its decoration of more than 300 conchas (stone shells), la fachada de las Escuelas Mayores (the façade in Salamanca University), and possibly one of the most characteristic Plateresque buildings, El Palacio de Monterrey (Monterey Palace), which gave rise to its own Monterrey or Neoplateresque style.

It is my understanding that the convent gradually emerged and grew during the 13th to 17th centuries. The Dominican Order were already well established in Salamanca, but it is written that the second flooding of the Tormes was the pretext for them to be assigned an area inside the walls where they could continue to grow (I think the second flood is called the Riada de los Difuntos, or Flood of the Departed, dating to 1256). Certainly the friars were already well established in the city in 1224, and in the second half of the 13th century they consolidated their success, especially in the academic area (see the Escuela de Salamanca). When they moved inside the walls they settled in the primitive church of San Esteban. With the passing of the years and the aid received, they built around the temple of the old parish of San Esteban, spreading out around the plot that bordered Monte Olivete. The first primitive convent would later be destroyed to build the current one, ca. 1610.

Because the convent bordered an active area to the south, occupied by houses and tanneries that faced the new wall, the noviciado (novitiate or house where novices were trained) was established to the east. In the area between the built-up urban zone and the convent would be the orchards and most probably constructions for the hostelry and nursing. It is known that there was also a patio with its well between the main cloister and the novices’ house, dating back at least to the 16th century.

With space being limited it became necessary to locate some rooms on upper floors, especially the bedrooms. This was typical of the evolution of monastic architecture, and there is evidence that the convent was almost completely restructured during this period of expansion. The eastern flank of the cloister housed the most important rooms, with sacristy and chapter on the ground floor, a study area on the first floor, and bedrooms on the upper floor. The location of the study hall was near the house of the novices and away from the urban bustle, but being located in the middle of the complex it was also accessible for external students. New floors would be raised, and a new refectory created on the ground floor.

It was in July 1492 that the Catholic Monarchs, as a favour for services rendered, issued a provisional order giving the Dominicans a large part of the Mount Olivete, including the street Arroyo de Santo Domingo and all the buildings, with the sole condition that a public street be left next to the city wall (the decision was executed in the following year).

The importance of Mount Olivete is due to its character as a relic, since it is considered a depositary place for the memory of the miracle of Saint Vicente Ferrer. Once ceded by the Catholic Monarchs and after displacing the tanners and other residents in the surrounding areas, the friars undertook to expand the site to the south (i.e. towards the present hospes). Part of the land was used to build what would be the hostelry. It was a semi-public area, which had to have its own entrance, as well as its own kitchen in which the menu differed from that of the friars.

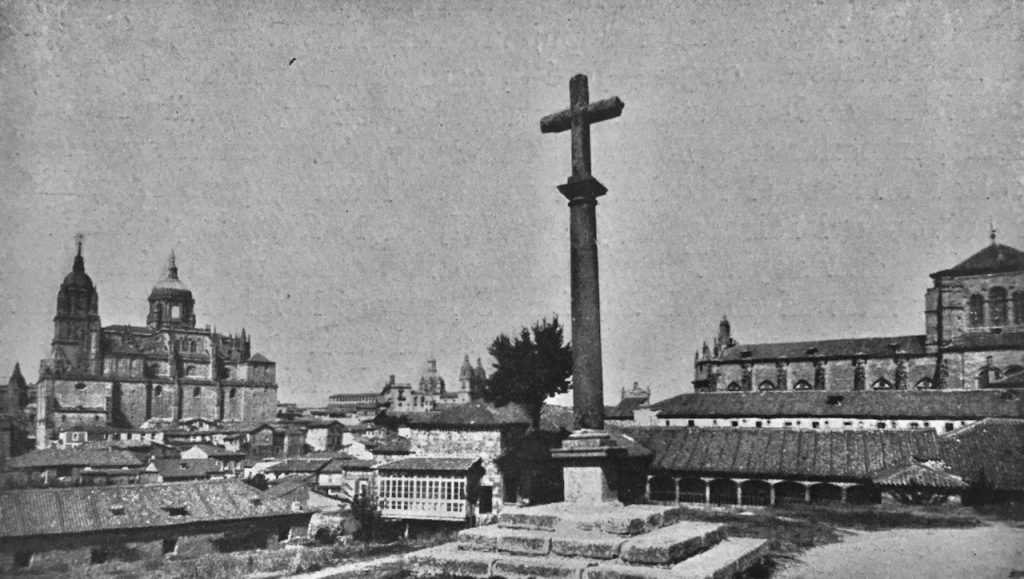

Above we have an old photograph of the cross set on the Mount Olivete, and below we have a photograph taken from more or less the same place today.

However the Dominicans did not obtain all Mount Olivete, for there are deeds of sale of lots in the area that date from the 16th century. So they established a policy of buying or exchanging plots of land on Monte Olivete that they did not own, the most important operation being the agreement with the Council in 1524 whereby the community of monks took over the area of the street next to the wall in exchange for other land acquired by the convent in the eastern area, in front of the current Paseo de Canalejas. Later still these lands would pass into the hands of the Diocese of Salamanca. It was during the Reformation that the complex grew, and the dependencies, including the church, were renovated and completed in 1610. The convent reached its maximum extension in 1819, when they acquired some land and buildings after the French occupation.

With the entry of the French into the city in January 1809, an unfortunate period for the convent began. The convent was then used as a shelter for the destitute and for those dismissed from other (regular) religious orders. Although the building did not suffer the fate of others in the city, which were practically demolished for the construction of military defences, it did suffer severe damage and looting by the troops. At the end of the war the restoration could be carried out through the sale of some rural properties of the convent. The church was reopened in 1813.

Worse for the friars was the confiscation of 1835. This meant the order was suppressed, the convent was lost, and its inhabitants moved to Ocaña, where the only remaining Dominican convent was in charge of collecting missionaries for the Far East.

The church, claustro de los reyes (cloister of the Kings) and sacristy remained property of the Diocese of Salamanca under the responsibility of the Brotherhood of Nuestra Señora del Rosario, founded by a Mendicant Order in 1470, and became, in 1840, the parish of San Polo.

The library, or part of it, was incorporated into that of some universities, including Salamanca, and its archive was sent to the National Historical Archive in Madrid.

In its premises, paintings and other valuable objects from the suppressed convents accumulated, and were finally gathered together following the Order of July 29, 1835 of the Ministry of the Interior. They established a Civil Commission with the mission of “…examining, inventorying and collecting whatever contain the archives and libraries of the suppressed monasteries and convents, and the paintings, objects of sculpture or others that must be preserved”. These works of art ended up being transferred to the San Bartolomé school (Palacio de Anaya) where on October 10, 1848 the Provincial Museum was opened to the public.

The convent’s apothecary also disappeared, of which there is evidence of its first apothecary D. Antonio Torres in the year 1506. The rest of the convent’s dependencies, except for the area of the infirmary that had been left for the care of a small group of elderly friars (de Venerables), was turned into infantry barracks. However, the military left there in 1842, and the buildings remaining unoccupied for a long period during which some families squatted the empty rooms.

Only one year after the secularisation, the Royal Decree of February 19, 1836 was published, which established the sale of the clergy’s assets at public auction, i.e. the properties of the convent of San Esteban were sold off. In 1854, a barracks was installed in the convent again, this time for the cavalry, which remained there until May 24, 1880. A good part of the convent itself, still in poor condition, awaited the return of the Dominican friars.

On November 4, 1880, a group of French Dominicans who had been expelled in 1879 by the French government arrived in Salamanca. Along with them came some Spanish Dominicans who joined the group to soften the linguistic and cultural impact. The occupation was partial since the Royal Decree of April 1, 1862 had ordered the delivery of the claustro de los reyes (cloister of the Kings) to the Provincial Museum.

In July 1887 the French friars abandoned the convent and a group of Spanish Dominicans formed from the few who joined the French in 1880 remained. Only three years later the convent was named a national monument, but the Provincial Museum remained in the building until 1936, only then did the entire convent return to the Dominicans. Finally in 1947 the convent became the Faculty of Theology.

Most of the above text has come from a webpage dedicated “El Monte Olivete y el Convento de San Esteban” on the website “Salamanca en el Ayer“. It’s a shame that the history of the hospes site was not documented and available to guests. You stay in a historic building but know nothing of its past.

Our room

The corridor to our room sets the tone for the type of hotel and the type of room to expect, and we were not disappointed.

The room had all the usual features you might expect in a 5-star hotel room, e.g. decent size, flat screen TV on the wall, good looking bed, minibar, desk and seat, divan and table, Nespresso, etc. There was a separate walk-in wardrobe with a wall safe which you could carry away with you because it was not actually fixed to any wall.

The bathroom included a bath, double sinks, WC and bidet, and a shower (with a slight step).

For what may be irrational reasons I did not like the bedroom. The choice of a dull sand-grey decor, coupled with the small windows, made the room a little gloomy, and the multiple light sources just could not overcome that feeling.

The room, with the old style bathroom decoration, left me a bit depressed. I can understand the desire to retain an “old style” bathroom, but frankly I would have preferred a modern bathroom with a decent walk-in shower.

A closer inspection of the decoration and tiling in the bathroom told me that it was recent, and clearly the style (colours, tiles on the floors and walls in the bathroom, etc.) were a recent intentional refurbishment.

What was certain was that the divan had seen better days, and needed a complete overhaul or replacement.

The room service

The room service is divided into a “day and night selection” (24 hour), a “daily selection” (09:00 to 23:00), and some “signature dishes” (09:00 to 16:00 and 20:00 to 23:00).

The 24 hour offering included the usual jamón de bellota (€29), quesos (€27), empanadas de espinacas o atún (pastry of spinach or tuna at €17 each), gazpacho (€12), yogurt or fresh fruit. The “daily selection” included Caesar salad (€19), salmon bagel (€19), Croque Monsieur (€17), leek cream soup (€13), and cheesecake (€7). The “signature dishes” included entrecôte de ternera (€30), bacalao (€27), hamburger (€21), fresh pasta (€20), croquettes, etc.

Around 17:00 my wife and I each ordered the Caesar salad, with a Estrella beer. What arrived was a smallish salad, some breaded chicken pieces, a couple of cherry tomatoes cut in half, and a dressing (tasting industrial). I expected romaine lettuce, croutons, egg, anchovies, Parmesan cheese, grilled chicken, and a homemade dressing with olive oil, garlic, lemon juice, Worcestershire sauce, Dijon mustard, and seasoning. It’s acceptable to change the salad leaf, and drop the anchovies and eggs.

Frankly we were very disappointed. The taste was passable (because we were hungry), but we expected much more from 5-star hotel. At least the beer was good.

The breakfast

Breakfast was a totally different experience from the room service of the night before. It was held in the El Monje restaurant with its stone arches and wooden floor.

There was a compact but very extensive buffet, supplemented with a menu of eggs, tortilla Francesa (French omelette), churros, etc.

Conclusion

Possible for irrational reasons, I did not like this hotel, and would not stay there again. We will one day revisit Salamanca, and I certainly will look for a 5-star hotel with a modern decor and a decent bathroom and walk-in shower.

Unfortunately my wonderful wife Monique passed away at 17:00 on the 23 December 2023, so we will never revisit Salamanca together. Maybe one day I will have the courage to visit the city alone, but maybe not.