Where is Grytviken, and why is it now a heritage site?

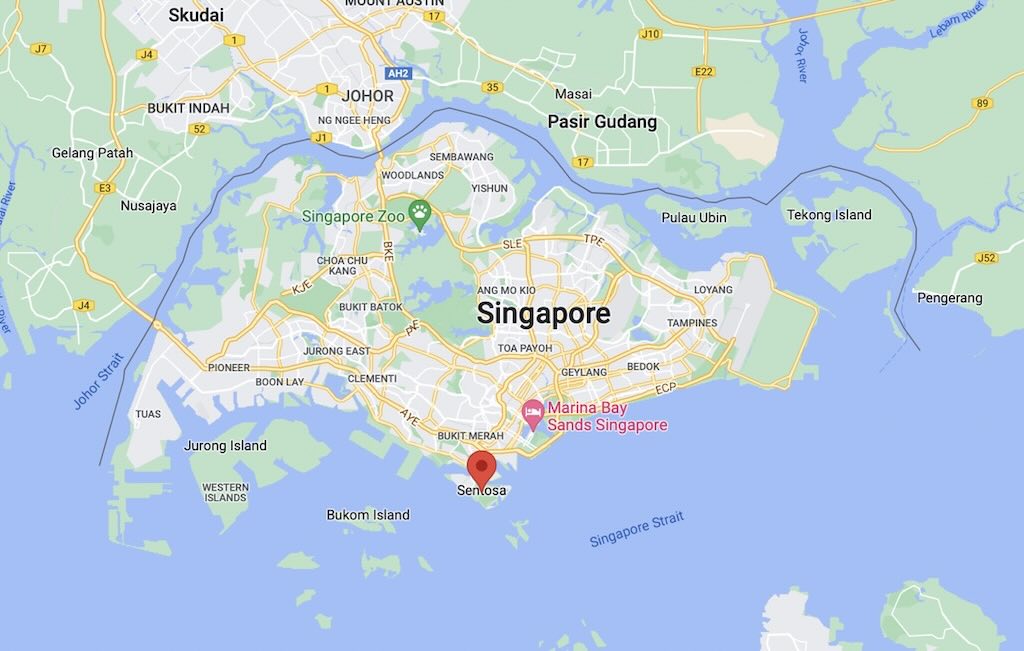

Wikipedia tells us that Grytviken is a hamlet on South Georgia in the South Atlantic. Formerly a whaling station, it was the largest settlement on the island. Grytviken is located at the head of King Edward Cove within the larger Cumberland East Bay, considered the best harbour on the island. The location’s name, meaning “pot bay”, was coined in 1902 by the Swedish Antarctic Expedition and documented by the surveyor Johan Gunnar Andersson, after the expedition found old English try pots used to render seal oil at the site. Settlement was re-established on 16 November 1904 by Norwegian Antarctic explorer Carl Anton Larsen on the long-used site of former whaling settlements.

Grytviken is built on a substantial area of sheltered, flat land and has a good supply of fresh water. Although it was the largest settlement on South Georgia, the island’s administration was based at the nearby British Antarctic Survey research station at King Edward Point. The whaling station closed in December 1966 when dwindling whale stocks made it financially unviable.

However whaling did not cease worldwide in 1966, far from it. While many commercial whaling stations (including those in South Georgia) shut down around that time due to declining whale populations and decreasing profitability, whaling continued Norway, Japan, Iceland, and the Soviet Union. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) only introduced a moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982, which took effect in 1986.

I was born in 1951, and it’s difficult to imagine that whaling continued until I was 35 years old. Whale oil and other derivatives were widely used across different industries, including:-

- Margarine – Whale oil was one of the main ingredients in margarine production until the 1960s when vegetable oils took over

- Soap – Many soaps, especially hard soaps, contained whale oil. Lux, Sunlight, and other brands would have used it.

- Cooking Fats and Oils – Some processed foods contained hydrogenated whale oil.

- Lubricants – Machinery, bicycles, and even watches used whale oil-based lubricants.

- Leather and Textile Treatments – Whale oil was used to soften leather and in waterproofing treatments for fabrics.

- Cosmetics and Perfumes – Spermaceti (from sperm whales) was a key ingredient in high-quality creams, lotions, and lipsticks, making them smoother.

- Candles – Some candles still used whale-derived ingredients.

- Vitamin Supplements – Cod liver oil was common, but some vitamin supplements contained whale-derived ingredients.

- Detergents – Industrial and domestic detergents sometimes relied on whale oil.

- Glycerin-Based Products – Toothpaste, skin creams, and even some pharmaceuticals used glycerin, which could be whale-derived.

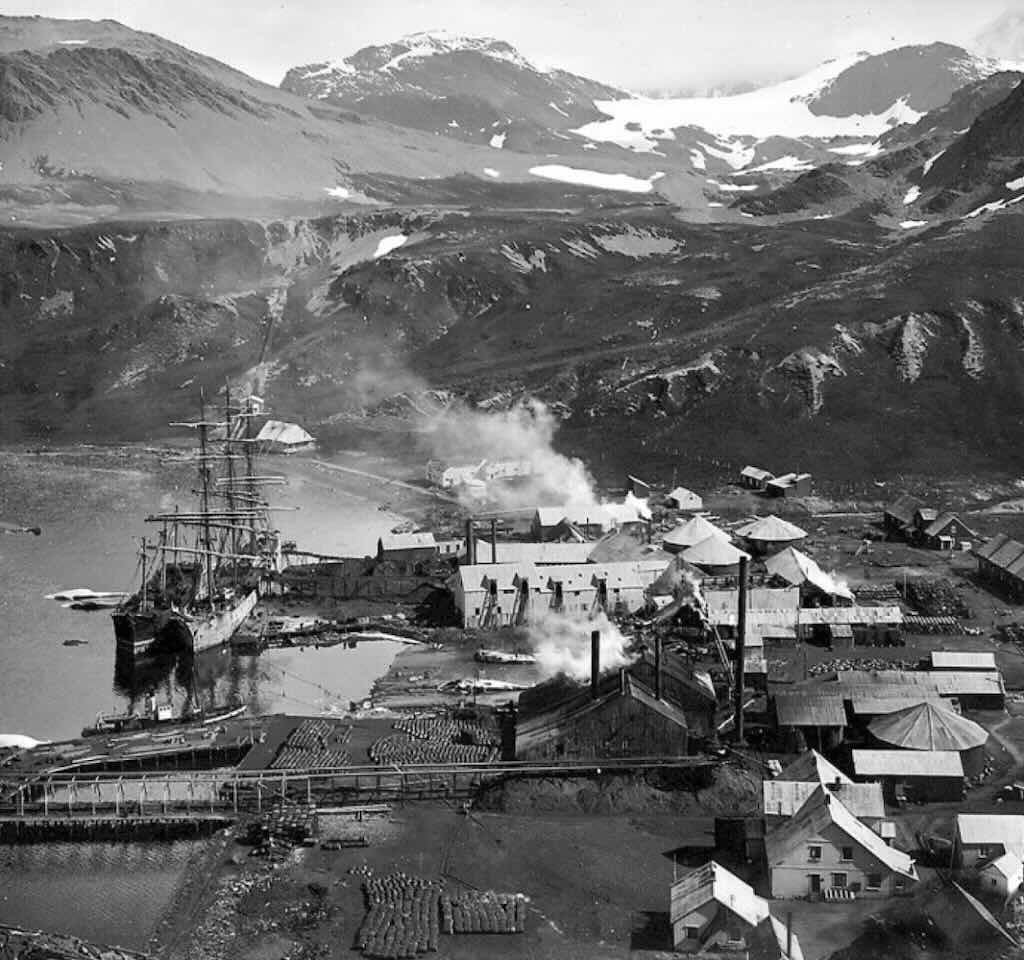

I’m certainly not an expert on this site, but my guess is as follows. The very large tanks are for storing whale oil. The large white building was for the manager, and the small building was the store. Then going down to the sea from the tanks, there were the centrifuges, with the small power house sitting before it. Then before the sea there is what’s left of the blubber cookery and boiling house, which have disappeared today. Next to it I think was the meat extraction plant. Across from the centrifuges was the bone cookery and the meat cookery, and possible just in view on the right the start of the guano factory.

It’s worth remembering the only 2-3 buildings were used for processing whales, the rest were workshops, storage, and accommodation.

The reality is that at Grytviken it is now almost impossible to sensible understood the process of whaling by simply looking at the remaining buildings. Leith Harbour is much the biggest of the whaling stations on the island, and it far more complete. But its buildings are in every sort of condition from total collapse to relatively minor damage, e.g. the steel frames remain in good order, but virtually all are missing cladding sheets from the walls and from the roofs. However, it would be a very expensive business just to get the buildings again structurally sound and wind and weather tight.

The best source of information on the state of the different whaling stations on South Georgia is the report “Inspection of the Disused Shore-Based Whaling Stations“, from 2011. It includes detailed site plans identifying all the builds, existing and otherwise.

Grytviken no longer has permanent residents but occasionally accommodates researchers and British administrative and military personnel. It is also temporarily inhabited during summer months by a few staff who manage the South Georgia Museum. The settlement has become a popular attraction for Antarctic cruise lines, with many tourists visiting the resting places of polar explorers Sir Ernest Shackleton and Frank Wild in Grytviken’s graveyard. Grytviken is located 900 metres west of King Edward Point, the administrative capital of South Georgia and its only remaining continuously inhabited settlement.

Cumberland Bay was originally named by Captain James Cook during his 1775 expedition. Cook named it after Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, the youngest son of King George II, who was known for his military leadership (notably in the Battle of Culloden). Later, as more detailed surveys were made, the bay was divided into Cumberland East Bay and Cumberland West Bay to distinguish the two major inlets.

King Edward Cove within Cumberland East Bay, was named after King Edward VII, who was the reigning British monarch when South Georgia was formally annexed in 1908.

Grytviken is the port of entry for South Georgia which all visitors are obliged to report to. So every visitor to the island be they fisherman, scientist, yachtsman or tourist must come to Grytviken. It is also now the only old whaling station that it is permissible to visit. It’s the only one to have had a thorough environmental clean-up, and the only one without the 200 metre exclusion zone.

The vast bulk of the buildings have been entirely demolished and all the material from them cleared away. It is understood that the timber was generally burnt and the corrugated iron and the asbestos was buried in pits. What remains are the concrete bases where the buildings stood, often with concrete up-stand walls for the footings for the wall framing. The steel framework supporting the larger elements of the plant in the main buildings remains so the cookery buildings still have framing and substantial amounts of plant remaining in position but all the more domestic building have been entirely removed.

The South Georgia Museum has an interesting webpage dedicated to the islands history.

Before we look at the open-air “museum” that is now Grytviken, lets us first try to understand the…

Life of a whaler

In the 19th century, seal hunting and whaling in the Antarctic were among the most gruelling and dangerous maritime occupations. The industry primarily drew men from the United States (New England ports like New Bedford and Nantucket), Britain (London, Hull, and Dundee), Norway, and later Germany and France. Crews were recruited from port cities, mostly from the working classes. Many were former fishermen, merchant sailors, or labourers with no formal education. Literacy rates among common sailors were low, though officers and harpooners often had some navigational or arithmetic training.

Recruitment took place in ports where ship captains advertised for crew, offering a share of the profits rather than fixed wages. Young men, often in their teens or early twenties, signed contracts that bound them to the voyage, which could last two to four years. Some were seasoned sailors seeking better opportunities, while others were desperate men avoiding debt, crime, or military conscription.

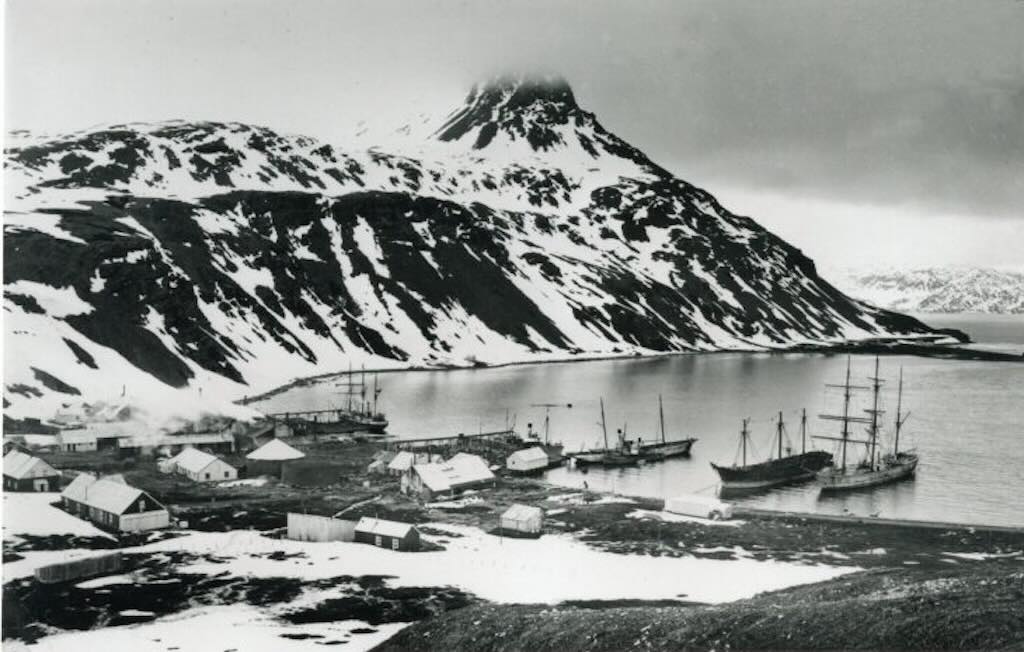

I’m told that the above photo dates from 1914, and includes Endurance, the ship of Ernest Shackleton.

Whaling vs. Sealing: Ships, Crews, and Hierarchies

Though whaling and seal hunting both targeted Antarctic marine life, they were largely separate industries with different types of ships and crews. Some ships participated in both trades if opportunities arose, but most vessels and sailors specialized in either whaling or seal hunting.

Whaling Ships: These were typically larger and designed for deep-sea voyages, equipped with tryworks (onboard furnaces for processing blubber into oil). Whalers carried whaleboats for hunting and retrieving their quarry from open waters. The crew hierarchy included captains, officers, harpooners, boatsteerers, and common sailors.

Sealing Ships: Smaller, often brigs or schooners, these vessels relied on quick, seasonal operations. They lacked tryworks, as seals were flensed (skinned) onshore, and the blubber was processed later. Sealing crews were often left ashore for months to hunt and skin seals, surviving in makeshift camps.

While some whalers turned to sealing when whale stocks declined or vice versa, most sailors saw themselves as either whalers or sealers, rarely switching between the two professions. Whalers viewed their work as superior, as sealing was often considered more grueling and required spending prolonged periods on desolate, icy islands.

The Whaling Process: Stages of the Hunt

The process of hunting and processing a whale was complex and involved multiple boats and crew roles:

Spotting and Pursuit – Lookouts stationed high on the mast scanned the horizon for whale spouts. Once a whale was sighted, the crew launched small whaleboats, typically six-man vessels, to row toward the target.

Harpooning – The harpooner, standing at the bow of the boat, threw a hand-held harpoon into the whale’s flesh, embedding a barbed head designed to hold fast. If successful, the whale would begin its violent attempt to escape.

The Nantucket Sleigh Ride – After being harpooned, a whale often swam at high speed, dragging the boat for miles before tiring. The crew had to carefully manage the line to avoid entanglement and capsizing.

Lancing and Kill – Once exhausted, the whale was approached again, and the mate or harpooner delivered the final blow using a long lance, piercing the heart or lungs until it bled out.

Towing to the Ship – Dead whales were lashed to the side of the whaling ship and towed back for processing. This could take hours or days depending on weather and sea conditions.

Flensing and Processing – Once alongside, the crew stripped the blubber from the whale in long sheets using flensing knives. The blubber was then boiled down in tryworks, and the oil was stored in barrels. Bones and baleen were also salvaged for commercial use.

Grytviken and Other Whaling Stations

In the early 20th century, Grytviken, located on South Georgia Island, became a major center for Antarctic whaling. Established in 1904 by Norwegian whaler Carl Anton Larsen, it was one of the first land-based whaling stations in the Southern Ocean. Unlike traditional whaling ships that had to return to port, Grytviken had onshore processing facilities, including large flensing platforms, oil rendering plants, and storage tanks. This allowed for more efficient processing of whales, eliminating the need for tryworks on ships and reducing waste.

Other whaling stations followed, including Leith Harbour (also on South Georgia), Husvik, Stromness, and Prince Olav Harbour, turning the island into the most important whaling hub in the South Atlantic. These stations often operated under Norwegian and British companies and were equipped with advanced machinery, such as steam-powered flensing winches and pressure cookers for extracting oil from bones.

Compared to open-sea whaling, the work at Grytviken and similar stations was more structured but still extremely dangerous. Instead of hunting whales from small boats, steam-powered catcher ships harpooned whales and towed them back to shore for processing. The industry here became more industrialised, with teams of specialised workers handling different stages of processing. This shift made land-based whaling more efficient but also increased the scale of exploitation, leading to severe depletion of whale populations in the Southern Ocean.

Earnings and Risks: Which Was More Lucrative and Dangerous?

Whalers generally earned more: A successful voyage could yield thousands of barrels of whale oil, making the business highly profitable, particularly before the petroleum industry reduced reliance on whale oil. Harpooners and officers could earn a substantial cut of the profits, while common sailors often received 1/200th or less of the earnings.

Sealers faced harsher conditions: Though sealing was potentially profitable, it was more physically punishing. Sealers endured extreme isolation, exposure to Antarctic weather, and high mortality rates from starvation or accidents. The mass killing of seals led to rapid population crashes, forcing sealers to travel to increasingly remote and dangerous locations.

Danger Levels: Whaling was deadly due to the hazards of open-sea hunting, capsized boats, drowning, and injuries from harpooning whales. Sealing had fewer immediate dangers at sea but was deadlier over time due to exposure, disease, and lack of medical help for injuries sustained on land.

Factory Ships and Larger Whaling Operations

By the late 19th century, factory ships began to appear, particularly among Norwegian and British fleets. Unlike traditional whaling ships, which had to return to port to offload their cargo, factory ships were self-sufficient processing centres at sea. These vessels were much larger, sometimes carrying 100 or more men, including specialised crews for flensing, boiling blubber, and storing oil. Factory ships often worked in coordination with smaller catchers, which would harpoon and tow whales back to the main vessel for immediate processing. This innovation drastically increased efficiency and extended the duration of whaling expeditions, allowing fleets to stay in Antarctic waters for months without resupplying.

Decline and Legacy

Despite the high mortality rate and brutal conditions, some whalers and sealers made their careers at sea, returning voyage after voyage. A few rose through the ranks to become officers or captains, but the majority ended their careers either maimed, impoverished, or buried at sea. The Antarctic whaling and sealing industries were driven by profit at the cost of human lives, with thousands of sailors lost to the ice, the sea, and the hazards of their trade.

Check out the resources on the Christopher Mitchell Company, which was a prominent Nantucket company that owned ships and dealt in oil, candle making, and selling ship parts. And the background to a story that is situated on the ship the Christopher Mitchell.

Grytviken’s whaling station

Grytviken’s whaling station was a small industrial complex made up of several specialised buildings, each designed to handle a specific stage of the whaling process.

This is 4K drone footage of Grytviken Whaling Station

There is also a more detailed “Visiting South Georgia 2024-2025”

This presentation is quite intriguing.

In the above photo we can see:-

- The museum, Shackleton’s grave in the grave yard, and the floating dock (where we landed in the Zodiacs).

- Gull Lake, and the power plant.

- Nybrakka means “New Barracks” in Norwegian, and it accommodated workers during the station’s operational years.

- The old ski jump was used by many of the Norwegian whalers.

- Bore Valley Dam provides fresh water.

- The Gunpowder Store, also known as the Magazine, was constructed in 1916 for the safe storage of explosives, primarily gunpowder and later dynamite, used for construction work.

- The Tide Gage measures the sea level.

- The Fuel Store (nothing known on this).

- The Gaol, constructed in 1912, serve as a jail, but is now a historic monument.

- and the Memorial.

The Gull Lake Dam provides hydroelectric power to the settlement. The initial construction dates from 1912–1914) and its primary purpose was to create a reservoir to supply water for hydroelectric power generation, which was essential for the whaling station’s operations. To increase capacity, the dam wall was extended in 1928, effectively doubling the reservoir’s volume. This expansion ensured a more reliable water supply for power generation, reducing reliance on imported coal. After decades of disuse following the station’s closure in the 1960s, the dam and its hydroelectric facilities underwent significant refurbishment ion 2007-2008. A new hydroelectric generation system was installed, utilising much of the existing infrastructure. Today it provides 250 kW of power to Grytviken and the nearby British Antarctic Survey Base at King Edward Point.

The Bore Valley Dam utilised a micro-hydroelectric generator rated at approximately 15 kW. It supplied electricity to the station’s cinema and other minor operations during the 1920s. There are plans to reinstate the micro-hydro scheme, in the dam provides fresh drinking water to the base.

A Tide Gauge measures the sea level relative to a specific point on land. These measurements are crucial for understanding tidal patterns and sea-level changes. In 2013, a continuous Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) station was installed on Brown Mountain, South Georgia Island. This station serves as a stable reference point for leveling a tide gauge at King Edward Point (KEP) research station. The integration of GNSS data with tide gauge measurements enhances the accuracy of sea-level monitoring by accounting for land movements (including tectonic movements), thereby providing more precise assessments of sea-level changes.

The Memorial probably commemorates the events of the Falklands War in 1982. During the conflict, Argentine forces occupied South Georgia, but were subsequently expelled by British forces during Operation Paraquet. Unfortunately an Argentine prisoner of war, Navy Petty Officer Felix Artuso, a crewman of ARA Santa Fe, was mistakenly shot dead after a British marine thought he was sabotaging the submarine. He is buried at Grytviken Cemetery.

The Church is not indicated but its very visible when visiting the site. The timber framed was erected in 1913 and is described as a ‘typical Norwegian country church’. The timber frame is clad in tonged and grooved vertical bratticed boarding and internally in tonged and grooved match boarding, both the interior and exterior being painted. The church is set at more or less 180° to conventional ecclesiastical practice with the entrance porch and doors in the east end and the sanctuary at the west end of the church.

Whale Processing at Grytviken

I think we can see the whale oil tanks in the foreground. The two brick buildings I think were meat cookery and the bone cookery. I might be wrong, but I think the brick walls, etc. have been removed during the environmental cleanup. This is one of the challenges when looking at old photos, there is a big different between before clean-up and after clean-up. We can see the flensing space where the whales were pulled ashore, and on the left there is the blubber cookery, which I think no longer exists.

On a good day about 30 fin whales, each about 20 metres long, could be processed in 24 hours, yielding 200 tons of oil. The largest ever processes was a blue whale 34 metres long.

Oil was extracted from the whale blubber in two rows of 12 tall Pressure Cookers. The strips of blubber from the flensing plant were cut into small pieces by a rotating cutter, carried up in a bucket-conveyor and dropped into the pressure cookers (pressekjeler). The blubber was boiled in steam until the oil separated out. Each cooker held about 24 tonnes of blubber which was cooked for approximately 5 hours. The oil was then piped to the Separator Plant for purification.

The boilers at the back raised steam for the cookers and driving the winches. Another boiler house has been demolished.

Bone and Meat Processing – The bones were crushed in the bone mill to extract any remaining oil. Meat and offal were used to produce fertilisers and meal, ensuring as little waste as possible.

Large lumps of whale meat, together with the tongue and guts, were dragged up the steel ramp and onto a Meat Loft. They were then cut into smaller pieces by steam-saws and dropped into rotating, pressure cookers where the oil was extracted.

The Meat Extract Plant was built in 1960 and became a very profitable part of the operation. Presses and evaporators extracted fluids from whale meat to make thick, flavourful and valuable product used for making soups and sauces. This plant speeded up the process by mincing, lightly cooking and then pressing the meat to extract the oil. Lumps of meat were taken by conveyor to the top and dropped into rotary cutters and distributed through presses, ovens and screens. This process produced a higher quality oil and a more protein-rich meat residue than the rotating cookers.

After the oil had been curated the meat and bone residues were fed separately into five cylindrical routing ovens. As the meat and bone residues passed along the ovens they were simultaneously dried by hot gases blown in from oil-fuelled furnaces.

After leaving the oven, the meal went through a crushing mill and cyclone separator that filtered meat and bone dust from the hot gasses. Finally, the meal was stored in bags in a huge L-shaped shed until they were taken by an overhead conveyer to a cargo ship.

Storage and Transport – The final whale oil was kept in large iron storage tanks before being shipped on supply vessels. The huge cylindrical metal tanks painted in dull colours, often rusted due to sea air. And they were located near the docks for easy access. Some bones and leftover meat were also sent away for processing.

There was also an Engine and Boiler House. Whaling was an energy‐intensive process, and this building housed the boilers and engines that powered both the try-works and other machinery around the station.

The workers barracks and administration buildings were simple, utilitarian wooden or metal-clad structures. The accommodation was very basic and had small windows to protect against the wind. The manager’s house was larger and more comfortable (now it’s the South Georgia Museum).

The summer population of Grytviken was about 400 men, mostly living in barracks. A maintenance team of 90 remained for the winter.

The New Barracks (Ny-brakka) were built in 1950 and centrally-heated, it housed a maximum of 100 workmen in rooms, mostly with four bunks.

The men ate in the Mess with its adjoining kitchen, and the butcher’s shop was nearby. There was a separate bathhouse and a separate Russian Barracks (Russebrakka) contained a laundry.

Most whalers came from Vestfold in south-east Norway, but others came from several other nations, especially Britain, Argentina and the Falkland Islands. The men worked 12-hour shifts, seven days a week during a season that lasted from October to March. Although Grytviken was a place for hard work and earning money to take back home, there were some facilities for recreation. There was a football pitch, a wooden ski-jump and a whalers’ cinema. The Whalers’ Church, a small white timber building with a steep roof, was built in 1913. It’s one of the few non-industrial buildings, it remains in good condition today.

The church is the only building at Grytviken that is still serving its original purpose. It undergone several restorations in recent years. The building is owned by the Government but managed by the museum team.

The building was planned by Larsen and designed by architect Adalbert Kitand, Larsen’s son-in-law. It was prefabricated in Stremmen, Norway and then shipped to South Georgia. In 1913 it was erected by the station workers in their spare time. The church was consecrated on Christmas Day 1913, and the two church bells, cast in Tonsberg. were first rung at midnight on Christmas Eve.

Laken wrote that “religious life does not wax strong amongst the whalers and left much to be desired”.

In addition there were docks for mooring catcher boats and a shipyard-dock for repairing vessels.

Later in the station’s history, refrigerated facilities were sometimes used to preserve meat and other perishable goods.

A narrow-gauge railway line was laid around 1912, not only in the whale cutting yard, but also throughout the town. Many of the rails were removed in the 1950s, but even today there are some surviving tracks and a wagon, for example under the bone platform. It was used for moving supples and moving solid waste. the steep wagons were move by hand or by winch. There is an indication that a track was laid to the dam to carry material for its extension in 1928.

The reality is that whilst well signposted and described, I found it difficult to link one particular building or piece of rusted machinery to one particular description.

So I’ve collected a few photos below to evoke the general impression of our visit.

I think above we have the blubber cookery.

Above I think are the fuel tanks, and below is the church, where I’m told people can still get married.

Above we can see the Petrel a 245 ton, 35-metre whale-catcher built in Oslo in 1928.

Petrel was one of the first whale-catchers to have a catwalk so the gunner could run from the bridge to the harpoon gun. She was converted for sealing in 1956 and the gun and catwalk were removed. Each summer Petrel visited the beaches around South Georgia and brought back cargoes of seal blubber.

This area is where the whale-catchers were maintained and repaired. Maintenance took place over winter so that vessels were ready when the crews arrived for the whaling season. Originally the vessels were pulled by a large winch up a slipway. The was also a floating dock built nearby.

Steel plates for the hull were shaped in the Platers’ Shop. There was an Engineers Shop, with a Foundry and Forge. An important job was to straighten harpoons for re-use. Thee were also Carpenters’, Pattern-makers’, Plumbers’ and Tinsmiths’ Shops, along with a Main Store and separate Rope Store.

Nearby there is the wreak of the trawler Viola, which was later renamed Kapduen and used for whaling. Nearby there must also be the Albatros, another delict whaler.

Everyone visited the local post office. So it was a bit chaotic with people buying postcards, writing postcards, buying stamps, sticking stamps, and posting them. I sent a few postcards to stamp collector friends, and they took about 6 weeks to arrive (airmail).

My advice would be to go to the post office first, then visit.

Finally, I visited the grave of Shackleton. I liked the “Entered Life Eternal”.