For centuries the Colle del Piccolo San Bernardo (Little St Bernard Pass) facilitated the transit of travellers, transhumant shepherds, pilgrims, merchants, smugglers, packmen, and migrants of all kinds. They had to overcome the dangers set up by nature, and occasionally human-imposed obstacles.

For millennia it was a route across the mountains, and only in modern times transformed into a material and military frontier.

The Piccolo San Bernardo is an alpine pass in the Graian Alps between Italy and France that connects the valley of La Thuile, a lateral valley of Valle d’Aosta, with Val d’Isère (Tarantasia). Its altitude, 2188 meters above sea level, makes it the lowest pass in the North-Western Alps and therefore the easiest passage between the Savoyard and Valle d’Aosta valleys.

Despite being the ‘easiest passage’ the pass closes every winter because of snow. In 2022 it closed on 3 November, and only opened again on the 25 May, 2023. The pass is known to be covered with 5 to 7 meters of snow every years, and the opening is a spectator event, check out this video from 2019.

Just below the pass, in Italian territory, is Lake Verney, one of the largest natural lakes in the Aosta Valley. The lake, of glacial origins and very deep (up to 40 metres) hosts a large quantity of fish and is therefore a destination for fishermen.

The pass has been frequented since ancient times, however the transalpine tunnels of Mont Blanc, Frejus and Gran San Bernardo has greatly contributed to decreasing its importance.

When the ski resort of La Rosière was started in the early fifties, its founders had already thought of a winter connection, across the pass, with their Aosta Valley neighbours of La Thuile. Since 1984, the Chardonnet chairlift and the Bellecombe ski lift, on the French side, and the Belvedere chairlift (see below), on the Italian side, have made this connection possible. The connection opens up to skiers an area, called Espace San Bernardo, of 3000 hectares and 160 km of slopes, served today by 38 ski lifts.

The Little St Bernard Pass was first crossed by the Tour de France in 1949 and has been featured three times since. In 2007, Montée d’Hauteville was climbed on stage 8 of the Tour de France. The pass was featured in the 2009 Tour de France Stage 16 on 21 July from Martigny (Switzerland) to Bourg-Saint-Maurice, 160 km, which also features the Great St Bernard Pass.

Our drive up to La Thuile

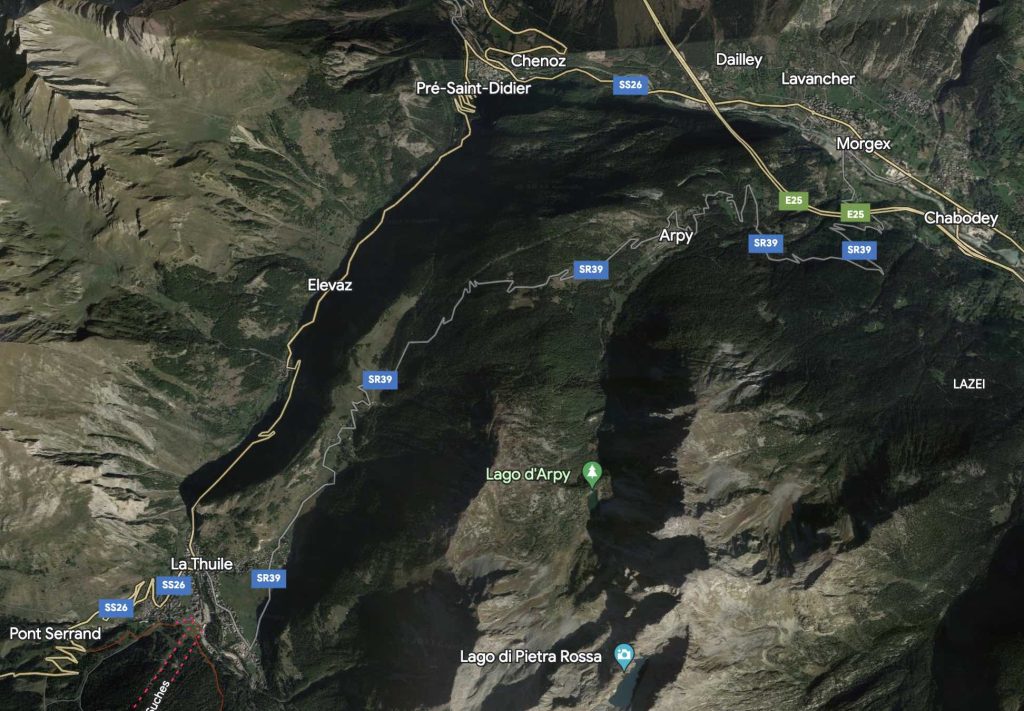

The Italian strada statale 26 (SS26) actually starts in Chivasso, outside Valle d’Aosta, However it runs through to Aosta, and then on to Sarre, Saint-Pierre, Villeneuve, Arvier, La Salle, Morgex, and finally arrives at Pré-Saint-Didier, From there it turns into the valley leading to La Thuile. It then continues to the frontier with France, at the Colle del Piccolo San Bernardo. In France the road becomes the D1090, which then connects to the route nationale 90 (RN90).

We have taken this drive many times, but prefer to drive up to La Thuile on the strade regionale 39 (SR39). This route goes over the Colle San Carlo at 1954 meters above sea level. The pass is 18.5 km long, running between Morgex and La Thuile. This pass has been featured a few times in the Giro d’Italia. Starting from Morgex, the ascent is 10.5 km long. Over this distance, the elevation gain is 1049 meters. The average percentage slope is 10%, but includes sections over 13%. The decent to La Thuile is 7 km long, with a drop of 530 meters (average slope is 7.6%). Below we have this route as seen on a motorbike.

Lago d'Arpy

Probably the most interesting feature of this particular route is that it provides access to Lago d’Arpy, a lake basin in the Arpy valley. Near the Colle San Carlo there is a parking, and a trail marked for Lago d’Arpy. The route is not challenging and is very pleasant, especially on summer days, and it takes around 1 hour to find the lake basin at an altitude of 2066 metres.

Walking around the lake anti-clockwise offers some impressive panoramic views of Mont Blanc, the Dente del Gigante and Mont Colmet.

There is also a path to the Lago di Pietra Rossa, however it is considered a medium-level hike.

Driving on to the Colle del Piccolo San Bernardo

Entering La Thuile we joined Italian strada statale 26 (SS26) for the second part of the trip up to the Colle del Piccolo San Bernardo. It was the 14 June 2023, but the pass had only been opened a few days, and there was still some snow on the ground.

The road from La Thuile to the pass is 12.8 km, and rises another 747 meters (average slope of nearly 6%). After Pont Serrand (1611 m), there are some hairpin bends, with a slope of 8-9%. From there the slope remains constant at 6-7% until the entrance to the vast plateau that precedes the pass. The drive takes you past Lake Verney, through four more hairpin bends, and then a short run to the top of the pass at 2188 meters above sea level.

The pass itself is not that exciting. There is a food and drink stop, some tourist shops, and some old customs buildings. Although I suspect those who have cycled up from Pré-Saint-Didier are happy to find a restroom, and something to drink. The best view of the pass is from a few hundred meters about the road, as seen below.

Just as a reminder, even if the pass is still open, it’s not all sun and fresh snow…

After driving back from La Thuile we stayed on the SS26 to Pré-Saint-Didier. This stretch is around 10 km long, with an average drop of 5%, although it can be up to 7% in places.

Just before entering Pré-Saint-Didier we passed a newly constructed barrier wall, This retainer wall was built after a landslide from the east wall of the ‘Mont de Nona’ on the afternoon of 25 December 2022. The rock was already known to be unstable, but there were heavy rain storms in the area above 2300 meters, which melted the snow cover of about 50 cm that was deposited in the days preceding the landslide. Associated with freeze/thaw cycles, with changes of about 15°C, the rock face finally detached.

The rock detachment itself, of almost 2,000 cubic metres, was accompanied by a landslide full of rocks, snow, and mud which favoured a flow over a long distance, knocking down the vegetation along the way. During the fall, the rock mass was shattered into blocks of various sizes. Some of them, imposing, invaded the state road, while others stopped just upstream from some houses.

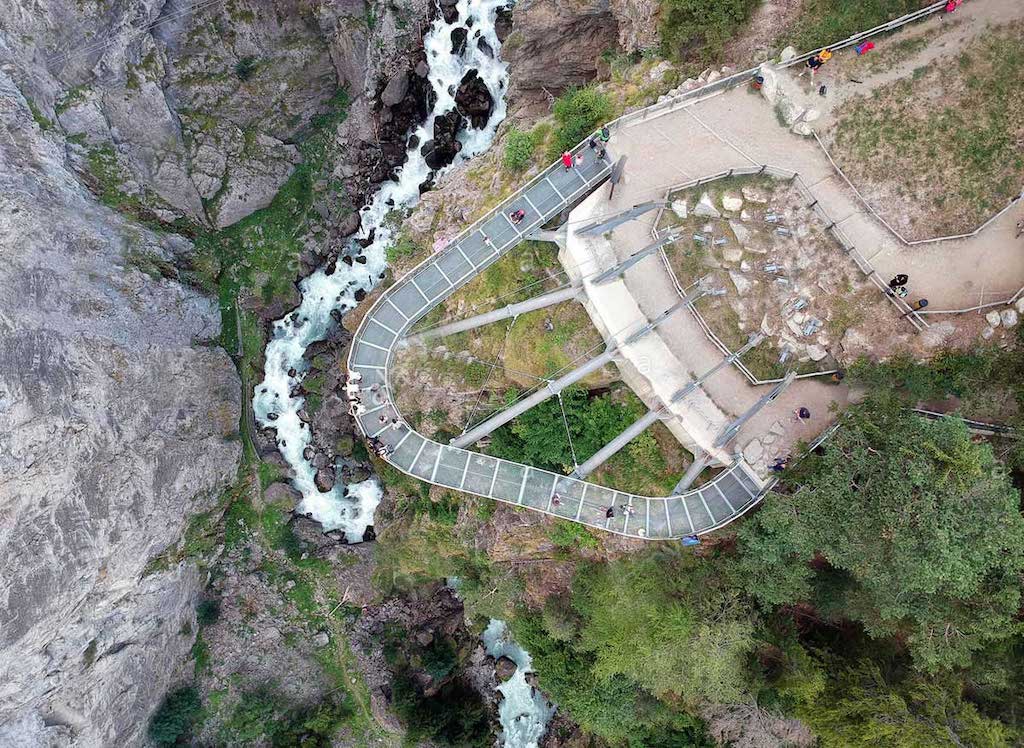

Panoramic walkway

Driving down to Pre-Saint-Didier on the SS26 there is the Mont Blanc Adventure Park. From the parking lot there is a flat dirt path that leads to a scenic walkway.

It sits over the gorge of the “Orrido di Pré-Saint-Didier”, and at a height of 160 metres, offers unrivalled views over the Mont Blanc range, the “conch” of Pré-Saint-Didier with the villages of Champex, Palleusieux and Verrand, as well as breathtaking views over the waterfall of the gorge and the thermal spring cave.

Who was San Bernardo?

The first evidence of human presence on the mountain dates back to prehistoric times, and is a large cromlech. From the ancient Breton ‘croum’ (circle) and ‘lech’ (sacred stone) this stone circle is made up today of 46 stones arranged along a circle of 72 meters in diameter. Today this cromlech is considered one of the oldest astronomical observatories in Europe. In fact, it would appear that the stone circle had a precise function, to indicate the summer solstice. On 21 June the sun sets exactly behind the saddle near the summit of Lancebranlette, a real natural sundial, creating a semicircle shadow for about half a minute that wraps around the cromlech, leaving only the central area in the light.

The Romans must have known this sacred aspect of the pass, because both Pliny and Petronius refer to a Gallo-Roman fanum (small temple), perhaps dedicated to a Celtic deity. And nearby there was a Roman mansio, a warehouse and accommodation for wayfarers and soldiers. Nearby, another Roman courtyard building might have been a sanctuary dedicated to the patron god of soldiers. A silver bust of Jupiter Dolichenus and some votive thanksgiving plaques were found there.

During the Middle Ages the pass kept the name linked to Jupiter, even if the cult was replaced with Christianity, the pass was cited as Mons Minoris Iovis, compared to Mons Jovis, denomination of the current Gran San Bernardo.

It is around the year 1000 that a certain Saint Bernard is thought to have arrived in this part of the Alps. A historical figure, perhaps born in Aosta, surrounded by an aura of legend. A tireless monk in the fight against paganism, his activity as an evangeliser and a missionary to the Alpine populations earned him the title of Apostle of the Alps. It was he who restored the old network of hostels, organising it as a free assistance service open to all. They were seen as rescue centres for the poor and sick, and places of shelter for pilgrims, merchants and soldiers. The construction of the hospices of both the Grande and Piccolo San Bernardo (1049-1050) is attributed to him.

Colle del Piccolo San Bernardo - a pass occupied since the Iron Age

Recent research has shown that the oldest and greatest density of archaeological remains date between 4500-2200 BC, when there were particularly favourable climatic conditions. Most of the evidence is concentrated within an altitude around 1000 meters above sea level, but with isolated examples of temporary occupations at altitudes around 2000-2500 meters, more abundant on the southern slopes in French territory. Often these are hearths of bivouacs suggesting temporary seasonal stays, but from this period inhabited areas appeared at higher altitudes no doubt linked to the existence of the first paths crossing the pass.

During the Iron Age the slopes of the hill were occupied by the Gallic populations of the Ceutroni on the French side, and of the Salassi on the Italian side. These same populations exercised control over access to the Piccolo San Bernardo, as the recent identification of a fortified village near the ravine of Pré-Saint-Didier seems to underline. It was during the repeated Augustan military campaigns aimed at ensuring control of the passes, that the native populations were replaced with special military units to guarantee safe passage.

We do not know if and to what extent the route of the Roman road through the pass followed more ancient routes, but there are texts that refer to a road crossing the pass in the pre-Roman age. There are references to the pass being used from that time, and communities on the two sides clearly provided services for those crossing the pass. As an example, the village of Saint-Rhémy was closely linked to assisting travellers in crossing the hill, including the recovery and burial of the bodies of those who perished during the winter season.

The Via delle Gallie (Latin via Publica) was a Roman consular road built by Augustus on the traces of pre-existing paths to connect Cisalpine Gaul located in the Po Valley with Transalpine Gaul, hence the name of the road. It was the first public work built by the Romans in the Aosta Valley, and was created to facilitate Roman military and political expansion towards the Alps, which then materialised with the conquest of Rezia and the Alpine arc under Augustus. The Via delle Gallie started from Mediolanum (modern Milan) and passed through Augusta Eporedia (Ivrea) bifurcating into two branches at the height of Augusta Praetoria (Aosta).

From Augusta Praetoria one branch of the road headed towards the pass of the Little Saint Bernard pass (Lain Columna Iovis) up to Lugdunum (Lyon), while the other branch was the Great Saint Bernard pass (Latin Mons Iovis) which then lead to Octodurus (Martigny), in the modern Canton of Valais, in Switzerland. In the Middle Ages, the route of the Via Francigena and the Leiðarvísir was superimposed on it, while in the 20th century, for long stretches, it coincides with main roads through the Valle d’Aosta and up to the Gran San Bernardo.

A frontier between Italy and France

The imperial recognition of the Duchy of Savoy (1416) placed the pass at the centre of a vast territorial lordship, a role which remain substantially unchanged while the capital of the Duchy was in Chambéry (the capital was moved to Turin in 1563). However, less than seventy years later (1629), the importance of the pass reappeared in a very dramatic way. Responding to the French expansionist initiatives, Carlo Emanuele I was forced to arrange the first defence plan for the region, trying to control the routes that descended into the Aosta Valley from the Piccolo San Bernardo.

Initially the defenses were established on the hills behind La Thuile, which allowed almost complete visual control of the route coming down from the pass. In 1630 this included defences on the Piccolo San Bernardo, but it’s not sure where these first constructions were on the pass. At the same time, on the other side of the pass, in Haute-Tarentaise, Louis XIII with Richelieu and his field marshals studied and began to build a much more powerful defensive system whose center of gravity was fort Saint-Maurice, a stronghold with earthen ramparts, defended by 3,000 men, near the current Bourg-Saint-Maurice.

Almost sixty years later, the threat from Louis XIV of France on the occasion of the Nine Years’ War forced Vittorio Amedeo II to prepare the mobilisation of his regiments, while the Conseil des Commis arranged for the defence of the western border of the Duchy of Aosta with the Tarentaise, a watershed moment which turned into a real frontier that would last for more than a century.

In 1706, during the War of the Spanish Succession, Duke Vittorio Amedeo II of Savoy and his cousin Prince Eugene won the Siege of Turin over a French army. In 1713, at the Treaty of Utrecht, the border of Piedmont was moved to the west, and in exchange for the Ubaye valley France ceded territories located to the east of the watershed line, i.e. the Briançonnais escartons of Châteaudauphin (Casteldelfino) and Oulx. In 1720 the Duke of Savoy and Prince of Piedmont became King of Sardinia, and from this date to 1861, his States would therefore constitute the Kingdom of Sardinia, often called “Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia”.

The reality was that the physical characteristics of the approaches to the Valle d’Aosta were not that easy to defend without a strong military presence. The most suitable place for a first line of defence upstream of Pont Serrand was at the opening of the valley of the Torrent du Reclus towards the Tarentaise (which today starts inside French territory).

The defensive line of what is known as the Retranchements Sardes (see above) had a layout that exploited the most useful features of the local terrain (flat areas, watercourses, gullies, cliffs, etc.). The instructions were clear, “Before the opening of the gorge which dominates the descent into Savoya, an entrenchment will be built flanked by two redoubts arranged so as to uncover the slopes and raze the ground”. The result was a continuous and transversal defensive line, across the Reclus valley which descended into Tarentasia. It was composed of a bastioned front line and two wings, equipped with redoubts.

Some parts of this defensive line were also exploited during WW II for mortar emplacements, and as home for the troops in position during the winter.

The actual route through the pass changed quite a lot during the 17th and 18th centuries. In part the road surface was local cut stone, but elsewhere the road surface was made of wood. For example in 1862 the old Roman bridge of Pont Serrand was still made of wood. Already in 1691 the idea was that it could be cut in case of an urgent defensive need. Also in the narrow valley of the Dora between La Thuile and the village of La Balme, the road ‘in many places was supported by beams’ (another defensive option).

Starting from 1793, new French military initiatives led major improvements to make the defence system more effective. The thickness of the dry-stone walls of the ramparts was doubled, sectors were completely redesigned and restructured with the doubling of the parapets and the construction of dry masonry trenches. Areas were created for artillery pieces and work on the road aimed at creating a constant slope. And ramps and hairpin bends were dug into the rock.

The cessation of use of the defense system followed the military events which, from the end of April 1794 and the same month of the following year, ended with the occupation of the La Thuile area by General Kellermann, head of the French Army of the Alps. Most of the fortifications were finally abandoned by the Azienda Fabbriche e Fortificazioni del Duchy during 1797, handing them back to the original owners of the land.

After the last use of these defence fortifications at the end of the 18th century, the area of the Piccolo San Bernardo pass was definitively transformed in 1861. Following the cession of Savoy to France, it became a border between Italy and France. A frontier which, parallel to the exercise of civil transit control, would be equipped, between the end of the 19th and the first fifty years of the following century, with new defensive fortifications.

June 10, 1940

On 10 June, 1940, Benito Mussolini, dictator of Italy, declared war on France and Great Britain. I found the following text, but I can’t validated the exactness of the description.

On June 11 the French shelled the pass and blocked the road going down to Bourg-St-Maurice, but the Italians had orders not to shoot.

June 21, the weather was not good, there was still a lot of snow, but the order to attack arrived from Rome.

At 08:00 Italian planes bombed the pass but did not hit anything important.

At 08.30 the Italians started to shell the pass. The Italian Alpini arrived 200 meters from the French fortifications, but discovered that they were still intact. The fog lifted and the French started to shoot back. Some shells hit the fortifications, but did not result in any fatalities.

At 12:00 it was thought that the French fortifications had fallen, so a column of about eighty Italian vehicles advances along the road. The French who have not suffered losses shot back and block the column. The Italians retreated, leaving the vehicles stationary on the road.

In the evening some Alpini got around the back of the French fortifications and cut the cableway and communications with the valley floor.

June 23, the fortifications were heavily bombarded, but the French stayed under rock shelters and suffer no losses. Italian infantrymen tried to advance on foot, but the French machine gunners block them again. The tanks broke through some fortifications, but got stuck in a minefield.

The French had managed to communicate with their command centre and asked to withdraw, but received a negative reply. They were ordered to remain as a forward observation post. The Alpini were still blocked on the pass, in front of the fortifications just 200 meters away!.

June 24, an armistice was signed in Rome (two days earlier the French had signed one with the Germans).

June 25, some Italian officers approach the fort waving a white flag. They ask the French commander what he wanted to do, and he replied that he awaited a written order. He invited the Italian officers to dine with him.

July 2, the written order to surrender arrived, and the French left the fortifications, receiving the honours of war.

The Piccolo San Bernardo Hospice and the Chanousia Alpine Garden

The provision of some form of hospitality for those crossing the pass is thought to have been interrupted with the fall of the Roman Empire and the invasion of the Longobards (568-774). And Bernard of Menthon (Saint Bernard) is thought to have restored the old network of hostels (ca. 1020). Hostels on the pass were certainly used by the Savoyard court in its movements from one side of the duchy to the other (possibly as early as 1051).

It’s also thought that after another reconstruction in the mid-12th century by Peter II, Archbishop of Tarantasia, the history of the Hospice seems to have evolved naturally. Only after the transfer of the capital from Chambéry to Turin in 1563, did the axis of the duchy’s road system move to Moncenisio, and both the pass and the Hospice lost its importance.

Restored several times, especially in the 17th century, the Hospice played a role in maintaining trading (and cultural) links between peoples on opposite sides of the pass. However, the pass was also a place of transit for armies, from and into Italy, and the Hospice often suffered violence and looting.

A Bull of Benedict XIV (19 August 1752), provided for the assets of the Provostship of the Gran San Bernardo, owned in the Savoyard state, to pass to the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus. This was one of the fundamental stages in the process of détente between the House of Savoy and the Papacy, which began with the Concordat of 1740. It obliged the Order to maintain hospitality on the Piccolo San Bernardo with the ambiguous formula pro pauperibus peregrinis (for poor pilgrims). It is not clear whether the obligation to give free hospitality concerned only poor pilgrims or pilgrims in general. At the beginning, the broader interpretation was preferred, even if the purse strings had to be tightened, reserving assistance only to those who actually needed it.

The services provided by the Hospice were entrusted to a rector appointed by the Order and chosen from among the secular priests of the diocese of Aosta, but the Church maintained the moral and canonical protection of the Hospice and of all the activities of the Order.

In the second half of the 18th century documents record considerable expenses incurred by the Order. To contain expenses, it was thought to eliminate the custom of feeding the passing muleteers and the shepherds, when about a hundred would go to mass in the Hospice every Sunday in the summer.

In 1794 the French troops, victorious at Passo delle Traversette, just south of the Hospice, crossed the pass, but the Armée des Alpes managed to occupy Piedmont only two years later due to the strenuous resistance of the Piedmontese.

The Hospice, was used as barracks, then looted and destroyed by the troops. It was left abandoned, while the Order itself, due to a Napoleonic decree which suppressed all religious orders and institutions, risked disappearing.

it was in 1826 that King Carlo Felice, Grand Master of the Ordine dei Santi Maurizio e Lazzaro, ordered the reconstruction of the Hospice which resumed it full activities ten years later.

In 1860, with the passage of Savoy to France, the pass became an international frontier. The Hospice found itself in French territory but, given the friendly relations between the two States and out of concern for the Order, it was decided to create a corridor that allows the property to remain in Italian territory.

This was the period of maximum splendor of the Piccolo San Bernardo Hospice, whose attendance increased in parallel with the spread of tourism and mountaineering, but also thanks to the abbot Pierre Chanoux, rector from 1859 until his death in 1909. It was he who began the excavations of the Roman remains and the cromlech, and he was also among the pioneers of the Italian Alpine Club founded by Quintino Sella in 1863.

From the small garden where he cultivated medicinal and rare plants, Chanoux came up with the idea of a garden of acclimatisation for the alpine flora, one of the first in the Alps. Inaugurated on 29 July 1897 with an imposing ceremony, it was cultivated with love and dedication by Chanoux, who sowed and transplanted many exotic species sent to him by similar institutions around the world.

Chanoux also managed to obtain a ban on hunting in the vicinity of the Hospice, while inviting mountaineers and tourists to avoid picking flowers, encouraging them instead to observe them in their natural environment.

When Chanoux died at the age of 81, the botanical garden, called Chanousia in his honour, was supervised by Lino Vaccari, a botanist who had been collaborating with the abbot for several years, and by the Milanese naturalist De Marchi, who contributed to the construction of a building to house a laboratory, a library and a guesthouse for scholars and researchers.

To better protect his creation, the abbot Chanoux had left it in his will to the University of Turin, but the latter had not thought it fit to accept the legacy. So the Ordine dei Santi Maurizio e Lazzaro took charge of the garden, and they managed to carry on the commitment also thanks to contributions from the Italian Ministries of Agriculture and National Education.

On the eve of WW II, the garden was home to more than 4,000 species of alpine plants from all over the world, and they published a specialised magazine, the Chanousia Yearbook. At the outbreak of the war with France, in September 1940, Chanousia was destroyed.

In 1943 the hill was occupied by German troops and in the winter of the following year it became the scene of fierce fighting, still testified today by the remains of the casemates and anti-tank works. The Chanoux Hospice was destroyed together with the botany laboratory. The books, collected with much love by the abbot, were torn up and scattered, and the rare species of Chanousia uprooted and destroyed.

Only 17 years after the end of the war, having resolved the problems of a legal nature relating to the ownership of the territory, which passed to France in 1947, it was established that the assets of the Order would remain privately owned by Italy on French soil and reconstruction started.

Serious economic problems meant that only in 1994 could restoration work on the Hospice begin and today the building is home to a small exhibition space with a tourist information point.

As far as the Chanousia is concerned, it was necessary to wait until 1976 for the reconstruction work to start. Promoted by the Société de la Flore Valdôtaine and carried out by the International Chanousia Association (created specifically for the management of the garden), it is now still presided over by a representative of the Order.

Chanousia has thus rediscovered something of its ancient charm, some plants survived and it has been possible to reproduce again the habitats already created by Chanoux. Currently there are at least 1200 alpine and snow species welcomed in the garden, of which about two hundred and fifty are from other mountain ranges around the world.

In 1988 the first laboratory organized by De Marchi was restored, and there is a guesthouse and a small museum which is home to memorabilia relating to the history of the garden. Among others things, there is a copy of the Papal Bull of 1752.

References

Andrea Vanni-Desideri, et. al. “Il Colle del Piccolo San Bernardo“

Roberto Sconfienza, “Il Sistema Difensivo del Piccolo San Bernardo“

Patrizia Figura, “L’Ospizio del Piccolo San Bernardo e il giardino alpino Chanousia“

“Le système défensif du Col du Petit-Saint-Bernard entre l’époque moderne et l’époque contemporaine”, with Nathalie Dufour and Andrea Vanni Desideri, “Le strutture difensive tra XVII e XX secolo”