In the late 60s I decided to try to study how traditional Chinese landscapes were created, or built up from a set of smaller naturally occurring components. I remember over a period of about 2 years I religiously copied many, many of those smaller components, trying at the same time to understand how an artist might use those components to create a larger work.

I’m not sure but I think this interest stemmed from taking brass rubbings with my Dad. Back at home I would copy out the rubbing on to separate sheet paper. I also started to sketch the churches and stately homes we visited. Initially we lived alongside a major set of railway lines, and I remember trying to draw trains (as part of train spotting). Also an occasional Sunday outing was to sit at the end of a runway and watch aircraft land and take off. I would try to draw them as well.

As an aside I also spend many hours building plastic models of trains and planes.

I will admit that my interest in Chinese landscapes was more motivated as a draftsman, than an artist. At school from the age of 11 I had taken classes in both building and engineering drawing. One of my most treasured possessions give to me by my father was a wooden draftsman board with it’s big wooden T-square, a set of drafting tools and templates, and a beautiful set of drawing instruments in brass and set in a wooden box.

I thought that none of my drawings had survived, but I was wrong. I did find one set of loose sheets, and I decided to scan and compile them here on this page. Why? Firstly, so I can throw away the originals, and secondly, who knows…

All the drawings seen below are mine, and date from at least about 1968-70.

The Chinese way to draw landscapes

I presume that there are many ways to draw Chinese landscapes, so I will try to remember what drove my particular interest (more than 50 years ago).

My understanding is that Chinese landscape painting emerged as a way to depict the virtues of the natural world as an inspiration for man. Often landscapes were added as companion scrolls to poems.

The better examples were certainly copied and re-copied, creating a kind of tradition in landscape painting. Perhaps the most noticeable feature is the amount of empty space, and then how a small number of apparently unrealistic looking components, often reproduced many times over, nevertheless created a feeling of a harmonious and idealised but natural whole.

Books have been written describing the philosophy behind the ‘way’. Not just the physical way to create the landscape, but also the way the landscape was first and foremost a part of a philosophical process. I may be wrong but one idea was that whilst the mountain range might not physically change, it would look different as artists built it from components. That process and the resulting landscape became a unique product of the artists inspiration. Poems would be different and the landscapes depicted would be different, despite the ‘geography’ (mountain, tree, fence, rocks, …) never changing. As an example, the mountain range remain physically unchanged, but the same artist saw it differently depending upon a particular moment in time, and depending upon their own passage through time.

I may be wrong (I am often wrong), but I understood that the empty space seen in many Chinese landscapes was not really empty, it had a physical existence as a void. It existed and had a purpose. A nice example was that a stream might be imagined given the shape and positioning of the rocks, etc. but we might not actually need to see any water.

You cannot transcend a medium until you have so mastered it that you are unaware of it.

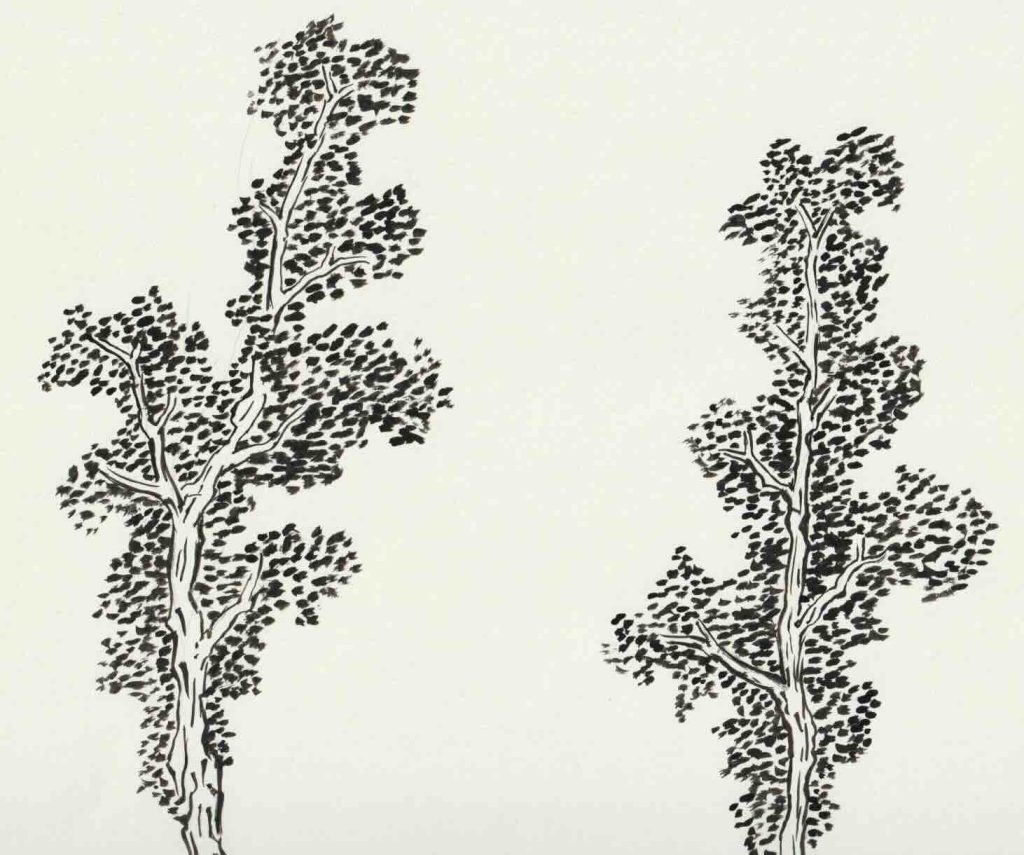

Again my own idea was that I should first try to ‘own’ the individual techniques (‘master’ would be too strong a term). Then copy, and gradually work to build my own landscapes. I remember working on leaves, plants, trees, clouds, rocks, etc., but stumbling at water, and never trying to ‘capture’ the techniques for representing things such as birds, animals, and eventually people. I did occasionally copy a person or landscape just to feel how much there was still to learn.

As mentioned above, I thought that those 100’s of sheets had been lost, but I still found a few sheets of my drawings of tree and leaves. So I decided to scan them, but I’ve no real idea what to do next, yet…

In trying to pull together my past thoughts, I was much inspired by “The Tao of Painting” (at least by the bits I understood), and by “Landscape Painting in Chinese Art“.

The “Tao of Painting” is available in the Internet Archive.

Trees and Leaves

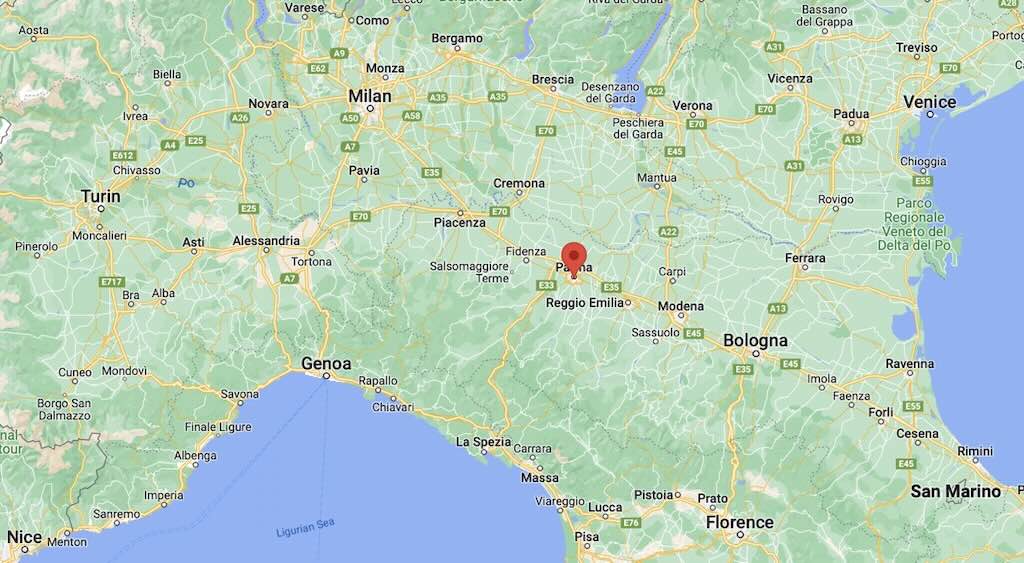

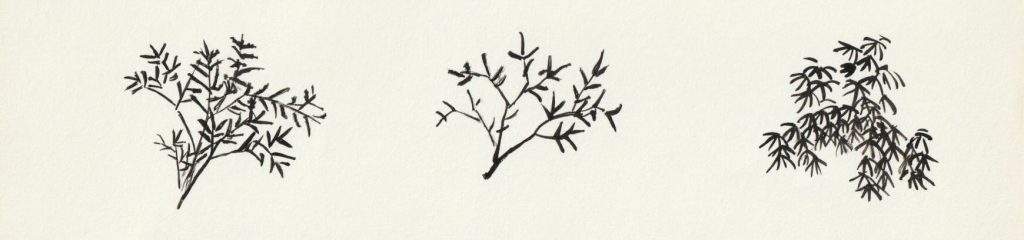

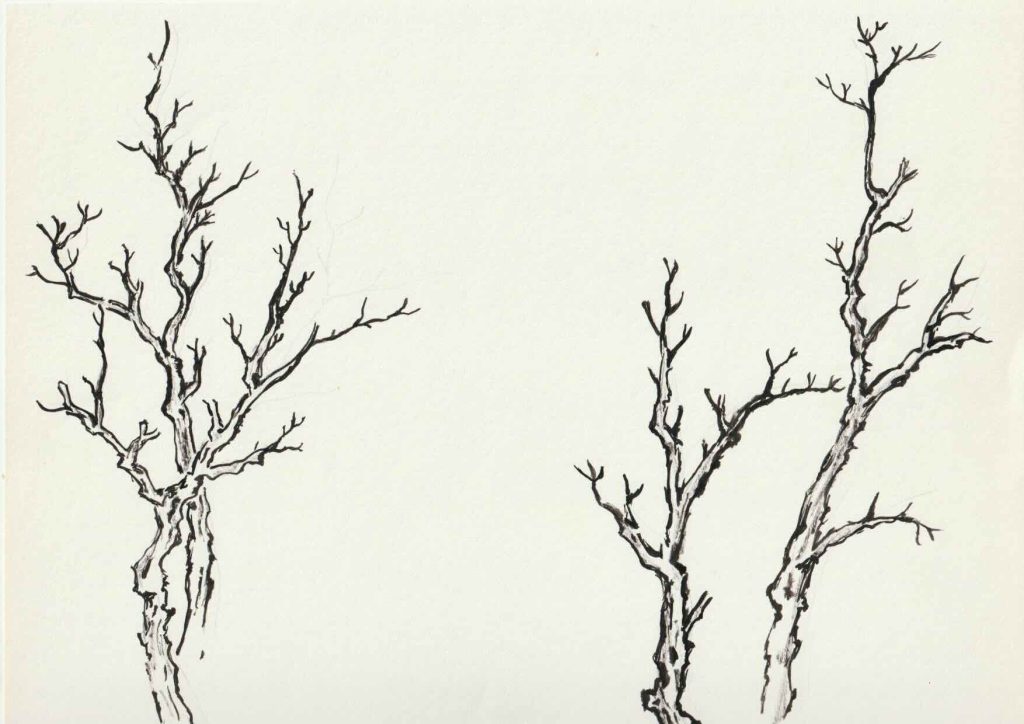

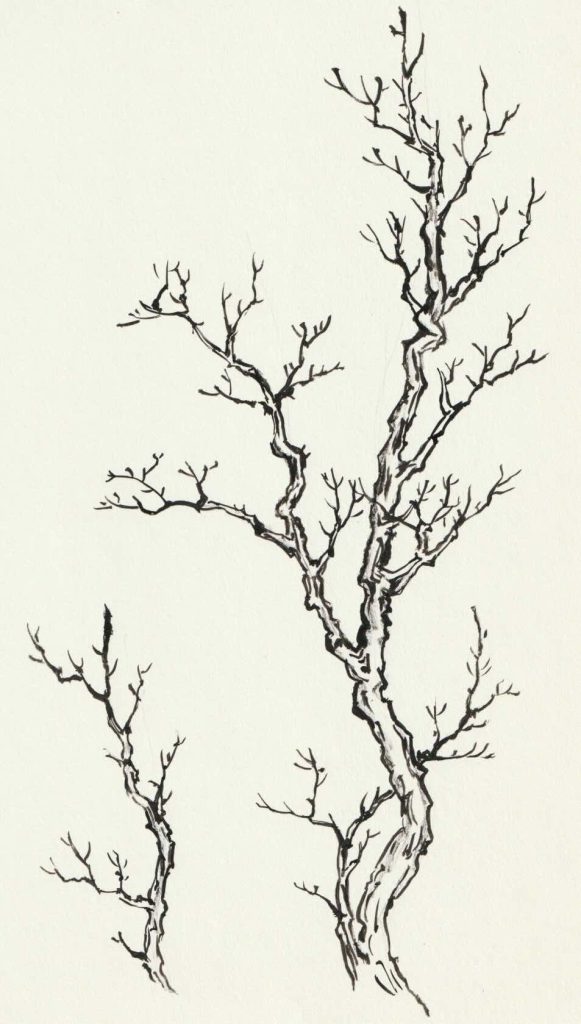

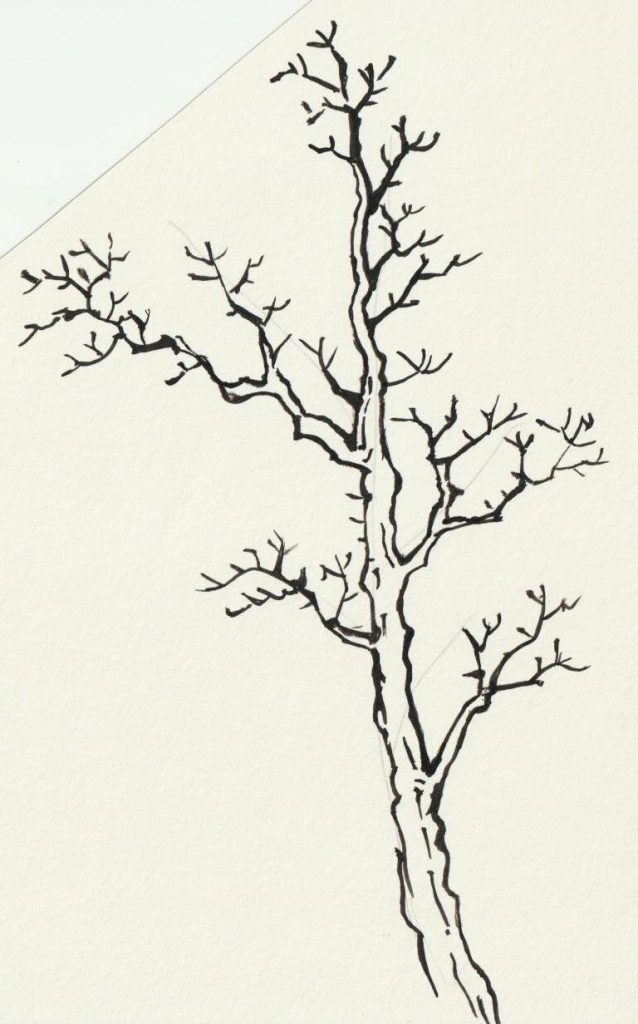

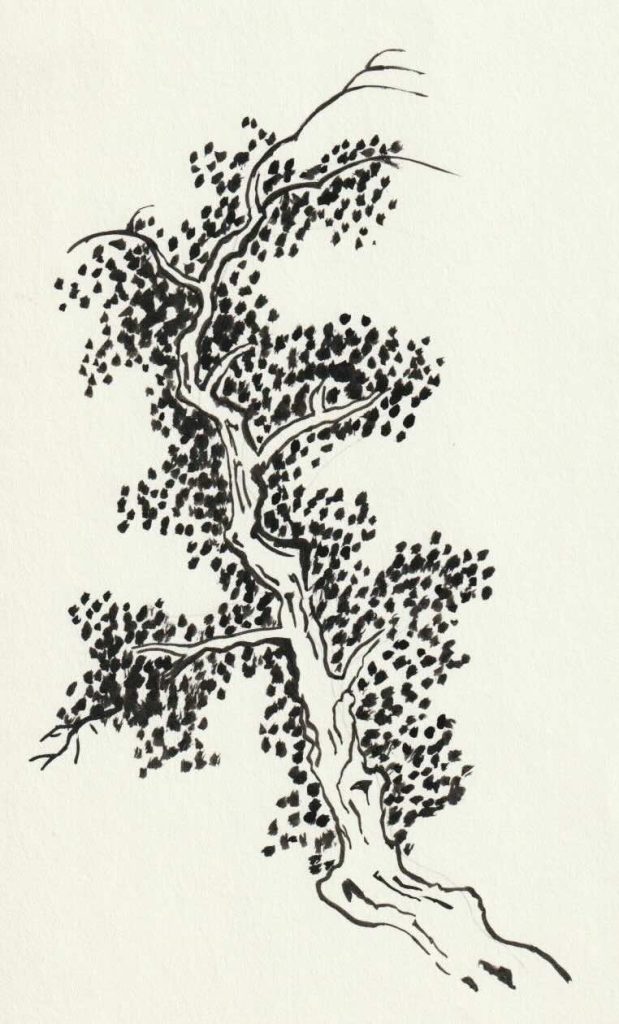

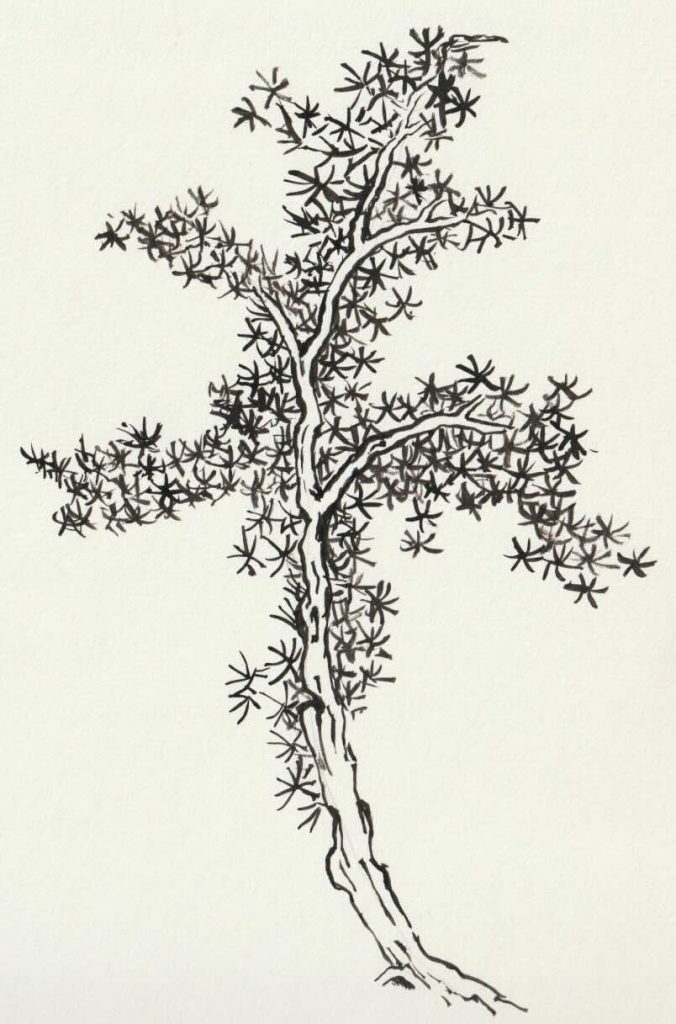

To draw a landscape it is important to first know how to draw trees. And to draw trees, one must start with a trunk and four main branches, then do foliage, and finally create a luxuriant forest. Drawing the bare form of the tree was considered the most difficult task. To capture the tension created by some branches pushing forward, whilst others seem withdrawn. The branches fork out from the trunk, creating the pattern for the smaller branches, and the “ten thousand details” all based upon the same simple principles. The idea was to get those four branches right, and everything else would fall into place.

The four branches represented the four limbs of man, and the four cardinal points. A tree could be the Tree of Life, of knowledge, family, religion, etc. Man was also seen as having four qualities, namely goodness, uprightness, fitness or propriety, and knowledge in the sense of wisdom.

Thus we see that there are solid technical instructions as to how to draw, yet there is also a deeper meaning that would give greater vitality to the brushstrokes. In my poor examples above we can see that they are not too bad technically, but we can’t see some branches energetically pushing forward (yang) and others giving way to them (yin). The action and balance of these two primal forces is missing, and would have taken much practice before becoming visible.

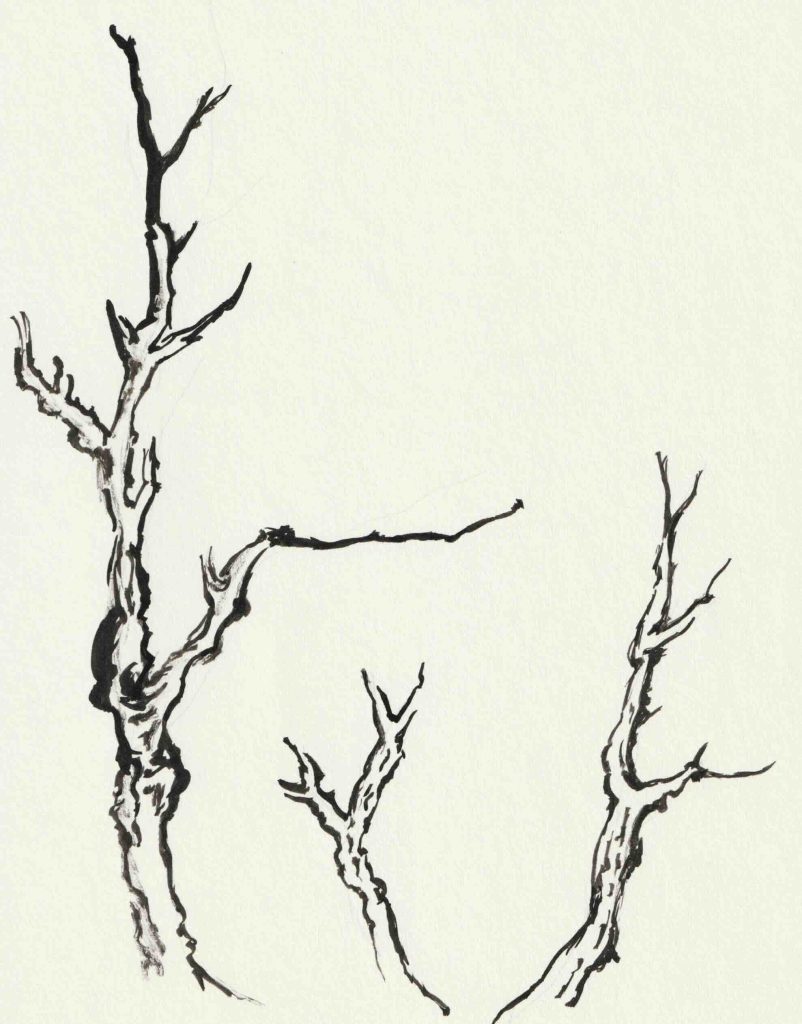

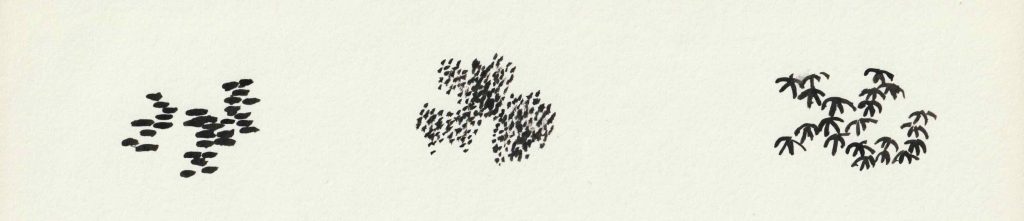

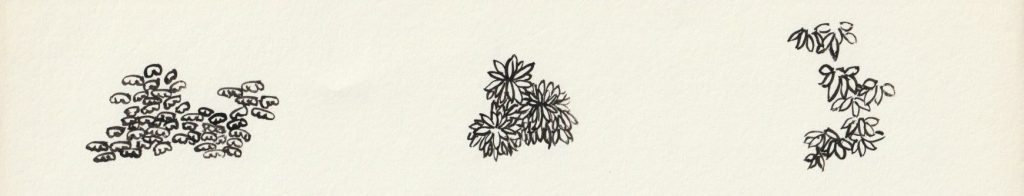

There is not much difference between dotting leaves and drawing them. Each artist develops their own brushstroke for leaves. My starting point was to copy the different techniques, but I never managed to develop my own style for leaves (or anything else).

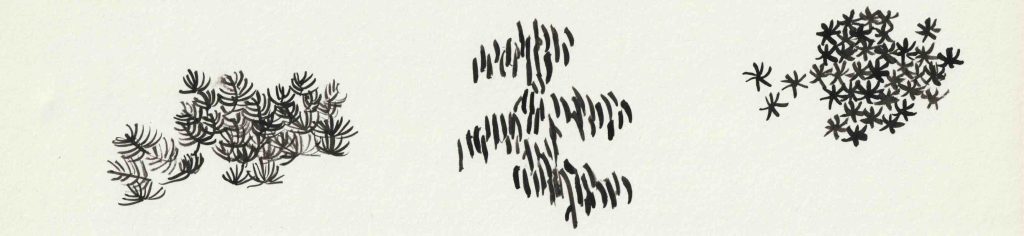

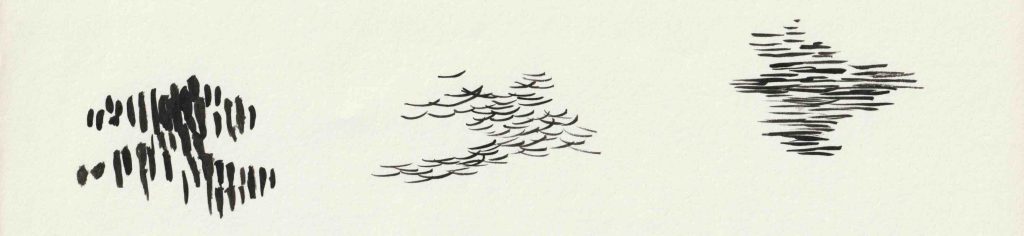

Above on the left we have a very simple dotting like little drops of water, in the middle dotting like a sprinkling of pepper, and on the right dotting in the form of a kind of stylised hat with two ‘legs’.

Above on the left we have leaves like the tracks of a little animal, in the middle we have plum blossom, and the right we have our stylised hat but now with only one leg.

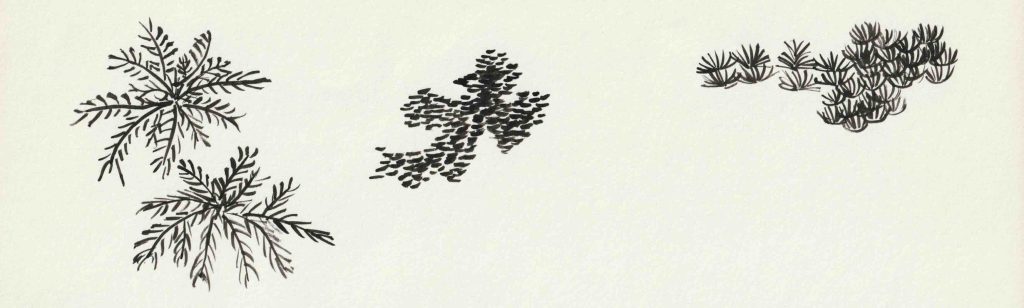

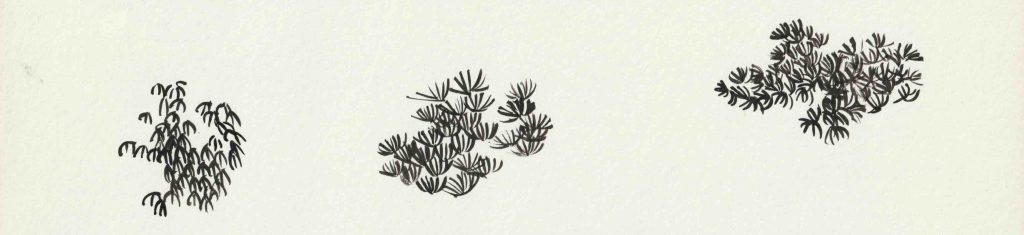

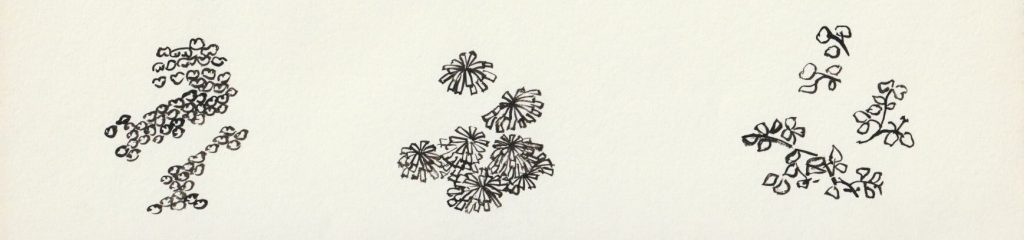

Above on the left we have pine needles, in the middle leaves hanging from a vine, and on the right the leaves of a chrysanthemum.

Above on the left we have an example of the foliage of a ‘red-leaf’ tree, in the middle the foliage of the cedar or cypress, and on the right the dotting of water grass.

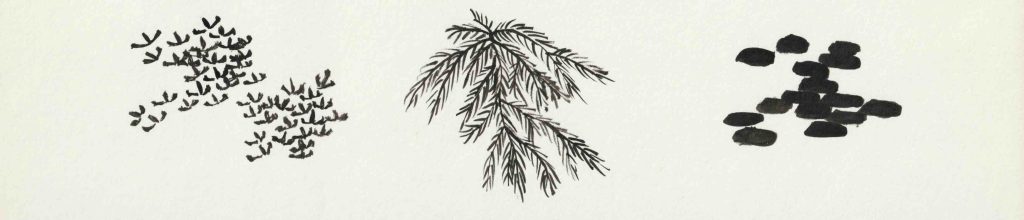

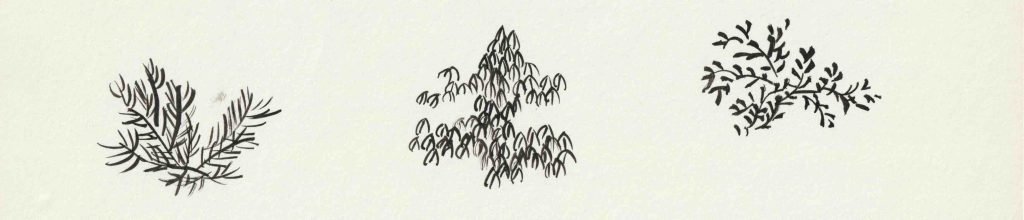

Above on the left we have three brush stokes coming together, then in the middle another type of water grass, and on the right blobs, like a whirlpool.

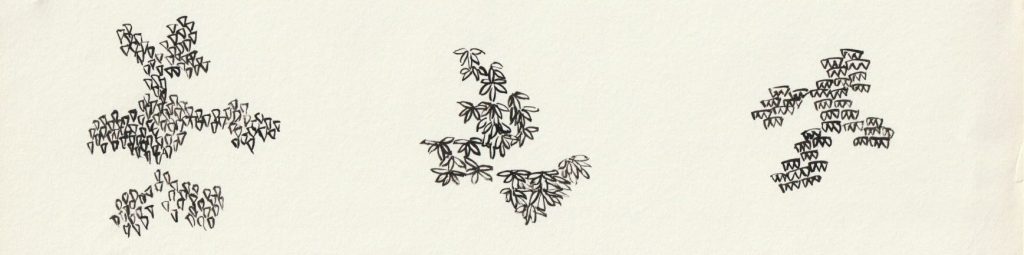

Above on the left we have dotting like blades of drooping grass, in the middle the leaves of a Chinese parasol tree, and on the right dotting in the form of sharp points. It’s interesting that the Chinese parasol tree is the female element, yin, to the male element, yang, the bamboo.

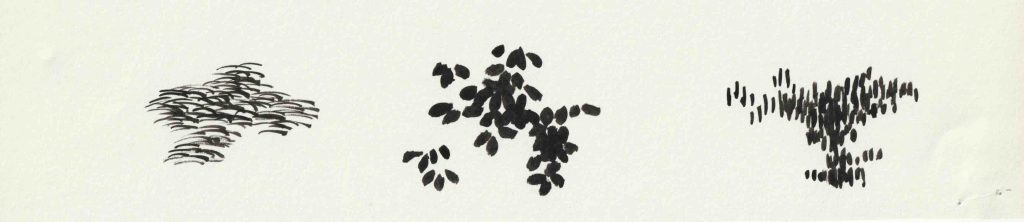

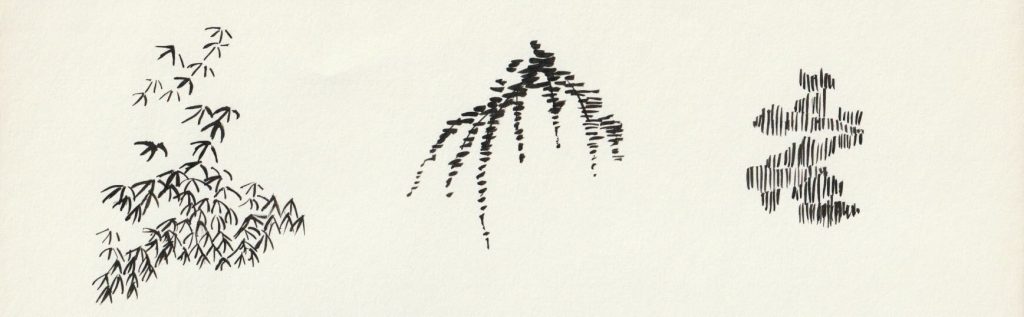

Above on the left we have simple vertical brushstrokes when the splitting of the hairs of the brush actually imparts a leaf-like quality, in the middle we have grass blades rising their heads, and on the right flat grass blades.

Above on the left we have fir needles, in the middle sharp pine needles, and on the right, leaves created by groups of three or five brushstrokes.

Above we have foliage pointing upwards, in the middle a leaf composed of three brushstrokes but with a slight hook added occasionally, and on the right a handful of loose leaves.

Above we have brushstrokes for a dense cluster of bamboo, in the middle the dotting of a hanging vine, and on the right falling leaves.

Above on the left and in the middle are different versions of young bamboo, and on the right a loose cluster of bamboo.

Above we have three example of water grasses.

Above we have examples of how to outline leaves.

This would have been followed by outlining and colouring, but unfortunately I no longer have those examples. I remember them well as outlines in one colour, and filling in the space in another colour, e.g. light flower blue and mineral blue, red and green, yellow and grass green, and some leaves were outlined but not filled, etc.

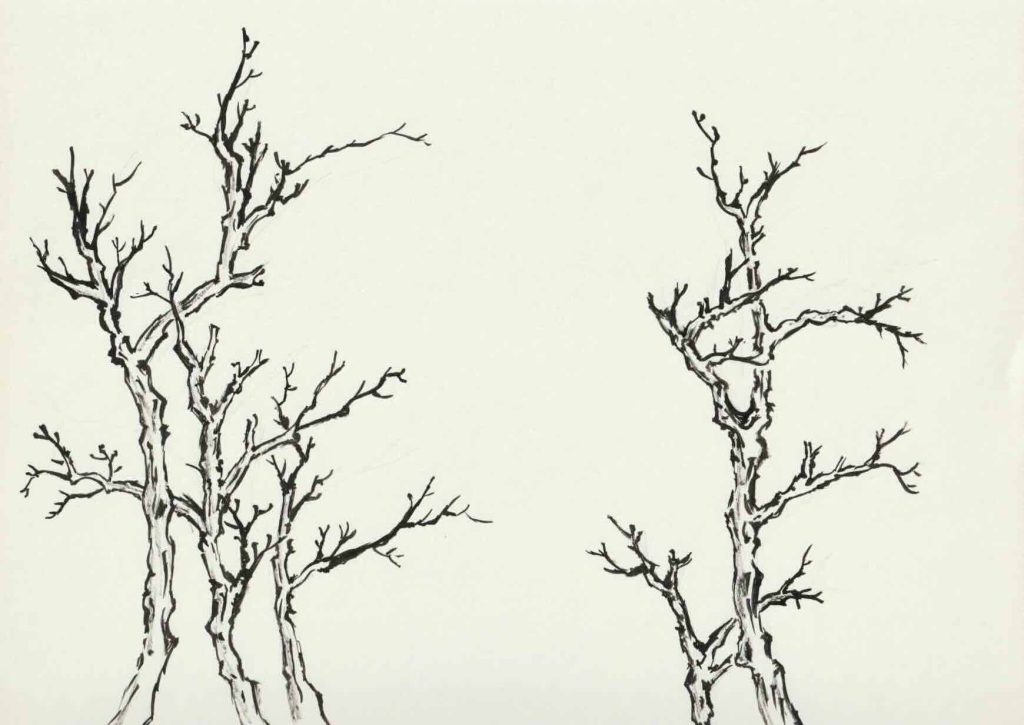

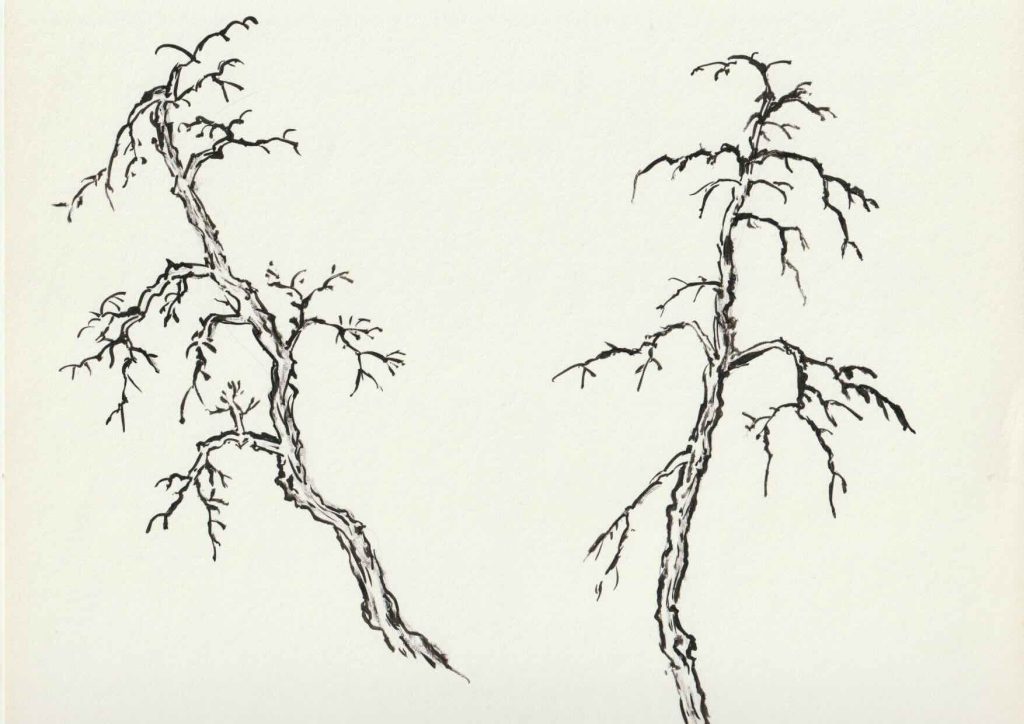

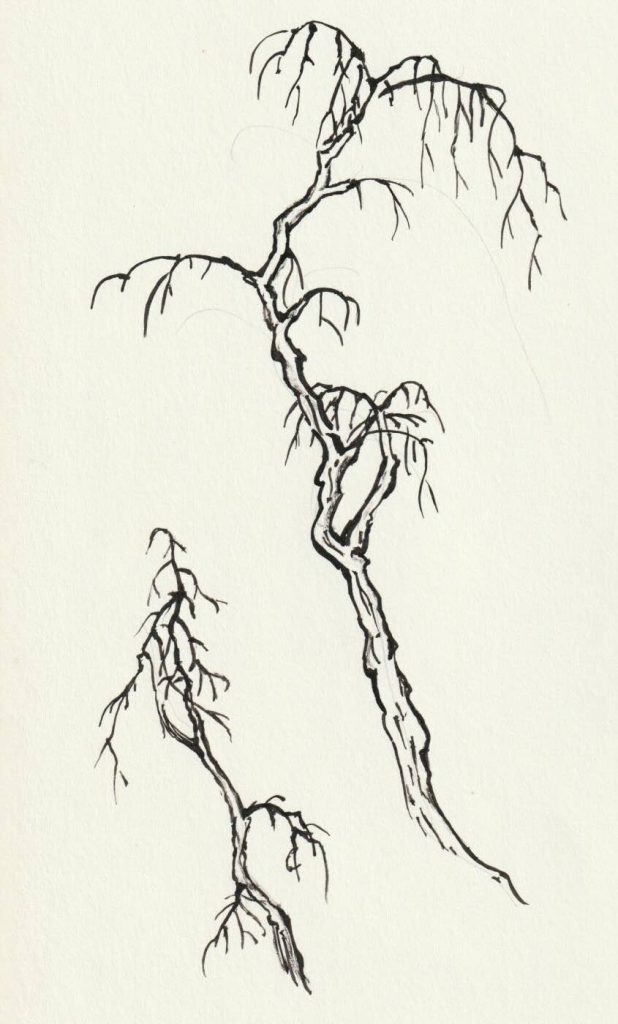

Once a single tree truck with branches had been ‘mastered’, then came the trucks and main branches of two trees, bare of foliage. Often a larger tree with a smaller tree added. A wonderful comment highlighted the ritual dance between old and new trees, “old trees should show a grave dignity and an air of compassion. Young trees should appear modest and retiring. They should stand gazing at each other“. Trees can cross each other or stand side-by-side, but separate (as seen above).

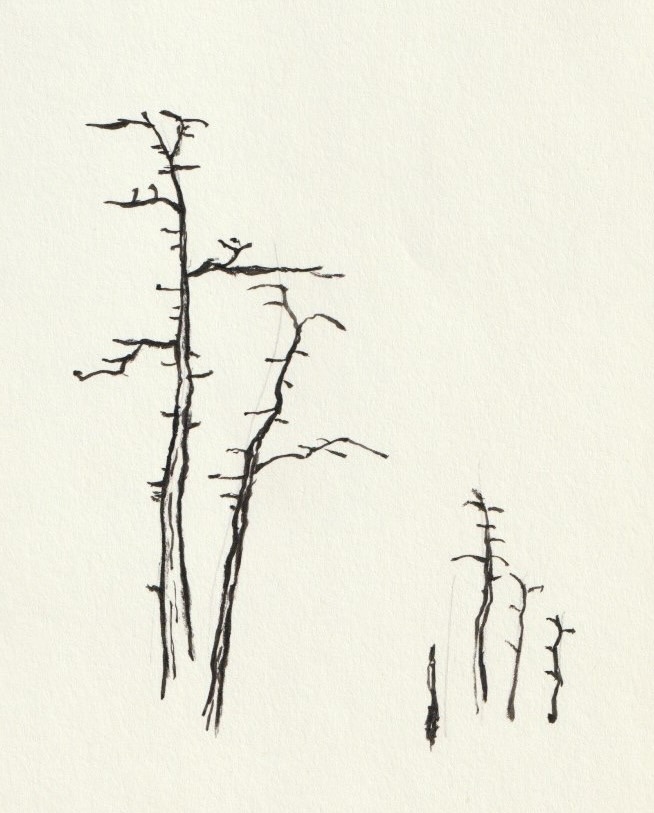

Naturally there can be many trees of different ages, and with different numbers of branches, but it’s important to avoid making them all the same height, with tops and roots at the same levels.

The key is to paint trees as if one yields a place to another, and that they stand together naturally. Above we can see the trunks and branches of large and small trees.

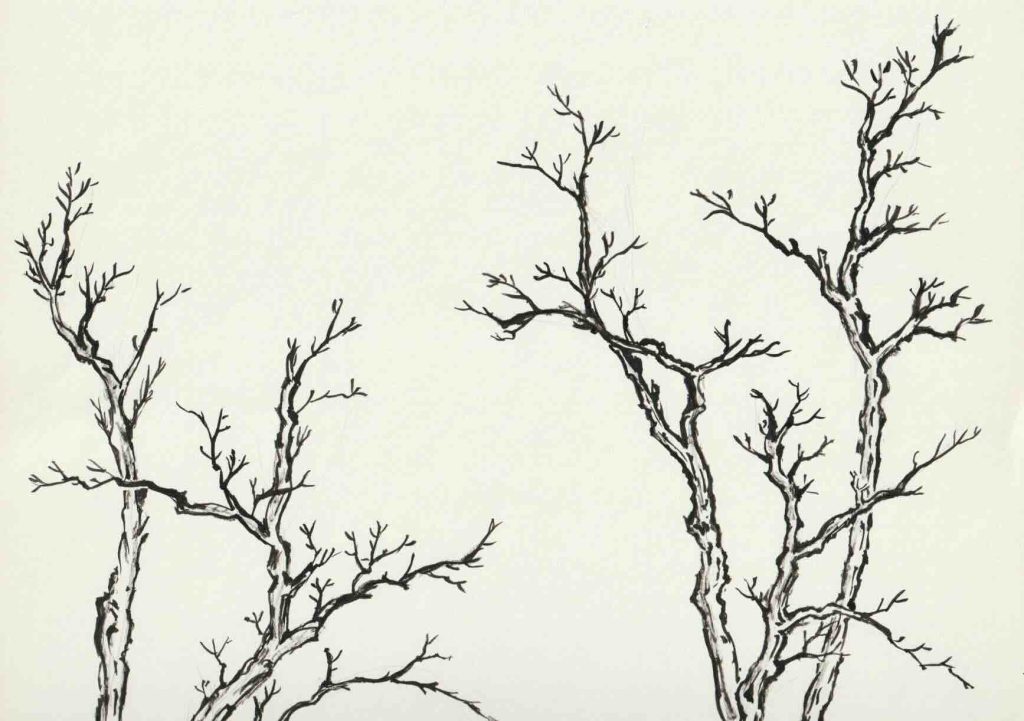

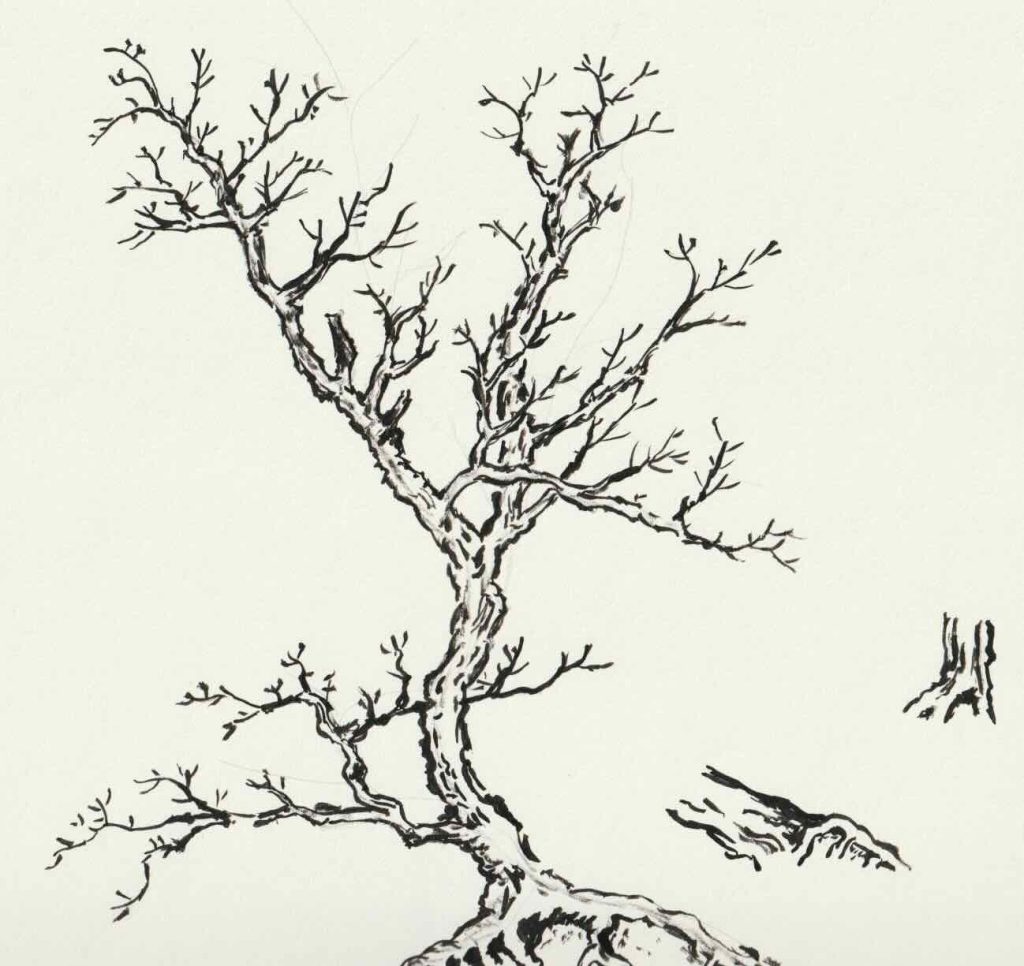

Next comes the task to compose groups of three trees, as seen above. The ‘ancients’ often painted trees in groups of five, but the reality is that any number of trees can be composed by painting single trees, pairs or groups of three.

The advice was that in autumn it was best not to place too many different kinds of trees together. Artists would use thicker ink at the top of a tree so that it stood out “like a crane amoung cocks“. A touch of fresh green would be added for trees in early spring. Trees with frost bite would have small touches of vermilion and umber to dot the leaves. Above we have what was called ‘stag horn’ brushstrokes.

Above is another style called the ‘crab claw’ or sharp pointed brushstroke (made with the sharp point of the brush). Artists often called this also the ‘dropping needles’ stroke. If painted with a light ink wash the effect was of a forest in the mist.

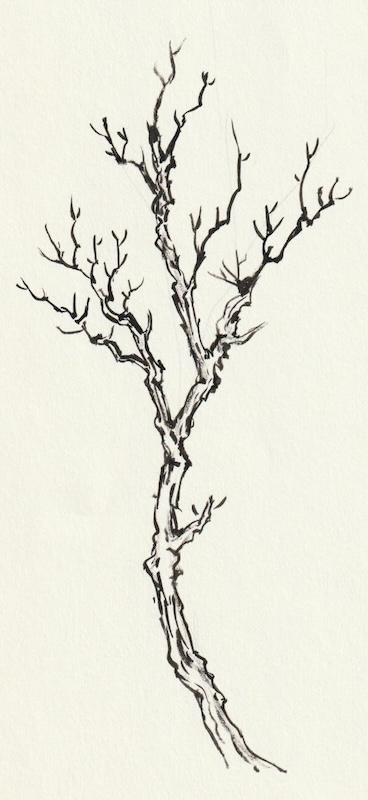

When trees grow among rocks, or are washed by springs, or cling to steep cliffs, the roots of old trees are exposed. They are “like hermits, withdrawn from the world, whose purity shows in their appearance. lean and gnarled with age, their bones and tendons protruding“.

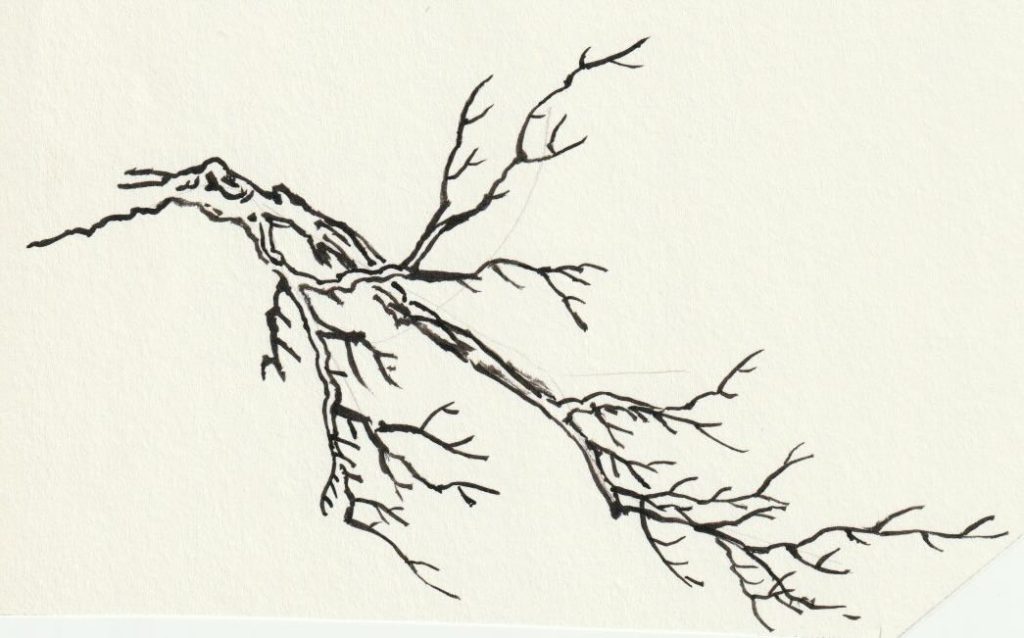

More specialised techniques were adopted to present a branch in the wind (above), or painting a tree in bud (below).

And there is always the option to add to or embellish a tree. Above brushstrokes are added to willow branches, and below smaller trees are “added where needed“.

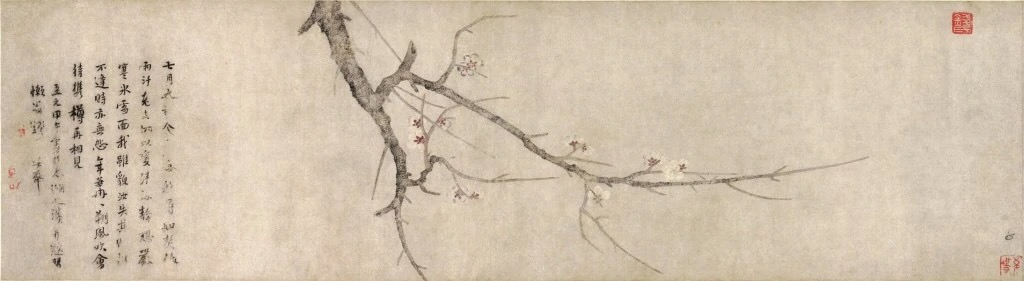

One of the easiest ways to add foliage, is to simply dot ‘mouse tracks’ often in groups of five. As seen below the impression given is one of plum blossom (along with an example of an artist).

Below we have on the left a tree with foliage dotted like a sprinkling of pepper, and on the right a tree with the foliage dotted in the form of chrysanthemum (and below that an example of an artists skill).

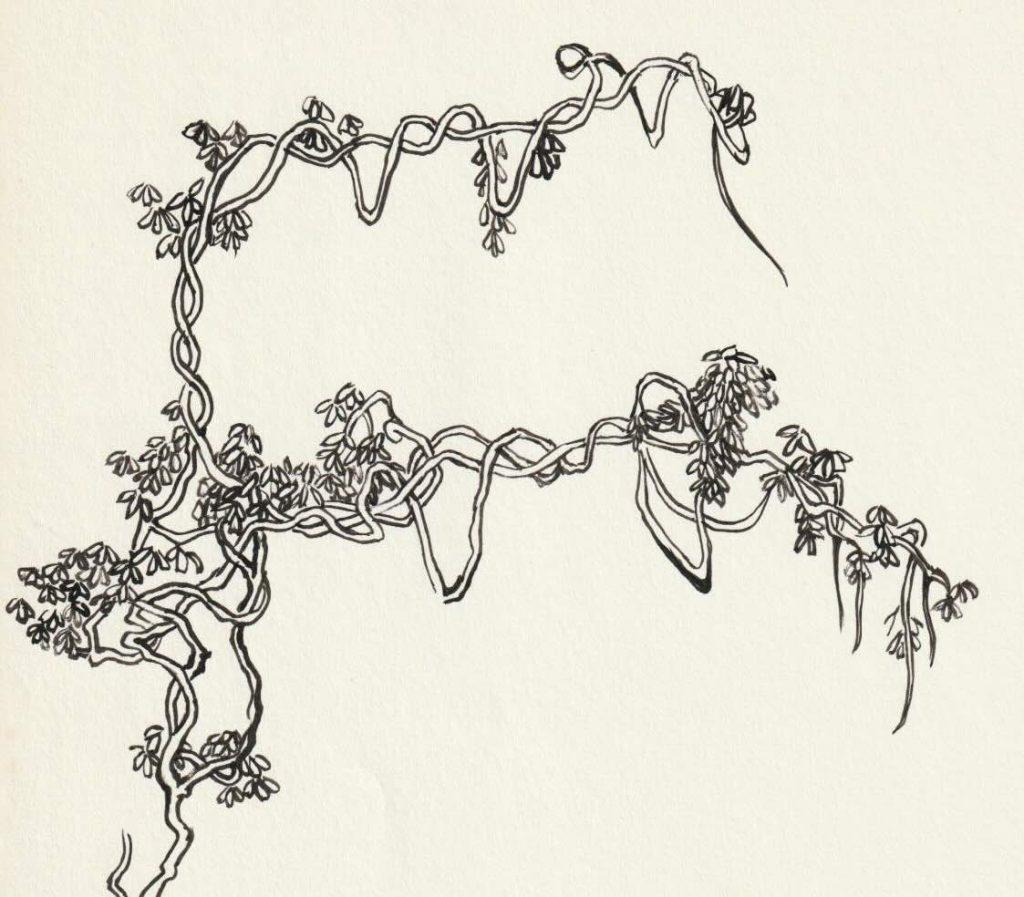

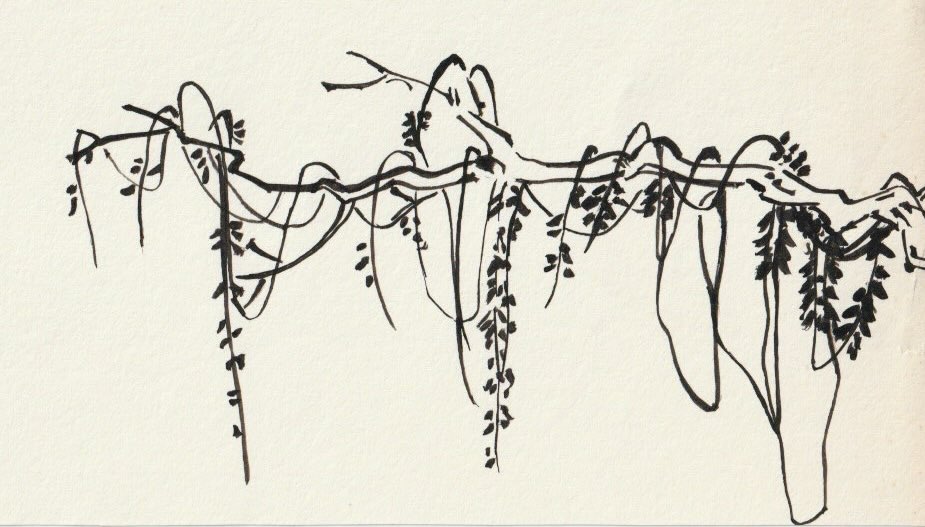

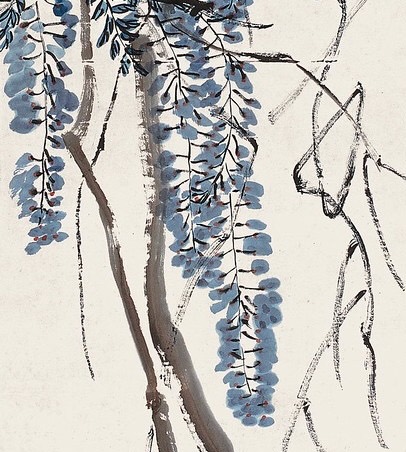

Of course there are many, many other types of plants that must be studied and practiced many time over. Above we have a vine growing on a tree, and below a vine growing on a cliff.

Above is one of my better attempts, yet it is much inferior when compared to the work of a true artist below.

Will I lift the brush again? Who knows…