In early June 2025 I participated in a New Scientist/Kirker tour package called “The Science of Champagne“, which evidently took place in and around Reims.

During the tour we were accompanied by drinks expert, Jonathan Ray, and the tour manager Graeme Coles.

Jonathan Ray is the drinks editor of The Spectator as well as a drinks columnist for The Field and Spear’s. He is also author of All About Wine, Bloodlines & Grapevines and Drink More Fizz!.

The group consisted of 6 people, 3 Americans, 2 English, and myself.

The hotel was the Best Western Premier Hotel De La Paix, a surprisingly good hotel in Reims (rated 8.8 on Booking).

PS – The phrase “Venez vite, je goûte les étoiles ! ” (Come quickly, I am tasting the stars!), is popularly attributed to Dom Pérignon, the 17th-century Benedictine monk often (though incorrectly) credited with inventing Champagne.

However, this quote is apocryphal in that there is no historical evidence that Dom Pérignon ever actually said those words. The phrase seems to have been invented much later, likely in the 19th or early 20th century, as part of legend-building around Champagne.

This trip is documented in two posts, this one covers Sunday and Monday, and the following post covers Tuesday and Wednesday.

Champagne II – au-delà des bulles!

And you can also check out:-

Champagne terminology

What we see above are called “plaque de muselet“, or just “plaque” to collectors (or caps in English). And this comes from the fact that the entire (wire cage + cap) is called a muselet (or “wirehood” in English).

At the end of this post I’ve included some French terminology, often specific to Champagne.

Sunday 08 June

The tour started at 18:00, with a welcome and Champagne tasting. Jonathan Ray introduced Champagne as both a region and a unique type of wine.

I was comforted in the following points:-

- The tulip-shaped glass or a white wine glass is preferred. These preserve bubbles and concentrate aromas. Flutes (which restrict aroma) and coupes (which allow bubbles to escape too quickly) are to be avoided.

- The hue of a Champagne should be pale straw, golden, with possible rosé shades. The colour can suggest the age and grape blend.

- The fineness and persistence of the bubbles can indicate quality and method of production.

- First gently swirl (very gently, to not lose bubbles) and take a first whiff. Can you detect fresh fruit, citrus, floral?

- Then inhale more deeply to look for complexity. Can you detect brioche, almond, honey, chalky minerality.

- The first taste is to determine your first impression. Is it fresh, soft, intense?

- In the mid-palate, you should be able to note texture (creamy, fine mousse), balance between acidity and sweetness, flavours like apple, toast, or spice.

- A quality Champagne should a long in mouth, with a lingering finish (aftertaste). Here you sense the minerality, dryness, and “elegance”, which I interpret as meaning the tastes “come together” in a harmonious way.

Ideally Champagne should be served at 8–10°C. Too cold the aromas will be muted, and too warm, the acidity can dominate.

The purist might add that one should never add fruit, ice, or mixers. True Champagne tasting is about purity and subtlety.

Champagne can be tasted with food, and the classic pairings include oysters, light cheeses, or even fried food for contrast.

As a starting point the Wikipedia article on Sparkling Wine Production is worth reading, as are the articles on the Traditional Method, Autolysis (alcohol fermentation) and Aging of Wine.

It also worth remembering that there are seven varieties of grape that can be used in Champagne. There are three that make up almost all Champagne production, namely the white grape Chardonnay, and the red grapes Pinot Noir and Meunier (formerly called Pinot Meunier). However there are also four minor historical, but authorised, grape varieties, namely Pinot Blanc (also known as Pinot Blanc Vrai), Pinot Gris (also known as Fromenteau), Petit Meslier, and Arbane.

The use of the last four is rare but permitted. The varieties Petit Meslier and Arbane retain acidity well in warmer years, which could be increasingly valuable when faced with climate change. However, there are good reasons for these varieties not being used, for example, Arbane and Petit Meslier are difficult to grow and highly susceptible to rot and frost.

Before the tasting it was worth pointing out that the different types of Champagne can be defined either by sweetness level (dosage the amount of sugar added after disgorgement), or by production type/style. Starting with the sweetness:-

- Brut Nature “Zero Dosage” means less than 3g/l sugar, and no sugar added. It should be extremely dry (a crisp, sharp taste), and many experts consider it the pure expression of the wine.

- Extra Brut is 0–6g/l sugar, and is very dry, but slightly rounder (a smoother, softer mouthfeel) than Brut Nature.

- Brut is up to 12g/l sugar, and is dry and has a palate-friendly balance, which means a mouthfeel that is neither too sharp nor too flabby with flavours (e.g., citrus, brioche, mineral) that are clearly defined but harmonious. This is the market leader in terms of production and global sales.

- Extra Dry (Extra Sec) has 12–17g/l sugar, and is slightly sweet despite the name.

- Sec has 17–32g/l sugar, and is noticeably sweeter.

- Demi-Sec has 32–50g/l sugar, is quite sweet, and is often served with desserts.

- Doux has more than 50g/l sugar, and is very sweet.

It’s worth noting that these classifications based upon sweetness or sugar content, are recognised in the European Commission Regulation (EC) No 607/2009 of 14 July 2009.

The below terms refer to how and when the Champagne was made:-

- Non-Vintage (NV) is a blend of wines from multiple years. The aim is to maintain a house style year after year, and is the market leader in terms of production values and sales.

- Vintage is made from grapes of a single year’s harvest. This is not produced every year, and must be aged at least 3 years on lees (but often much longer). It is considered to reflect both the terroir and the climate of that specific year.

- Prestige Cuvée (Tête de Cuvée) is the house’s top Champagne, and is often a vintage wine.

- Blanc de Blancs is made only from white grapes, typically 100% Chardonnay. It should be lively (good acidity and fine bubbles), fresh (clean, crisp), and elegant (delicate aromas, long, clean finish).

- Blanc de Noirs is made only from black grapes, usually Pinot Noir and/or Pinot Meunier. It should be fuller-bodied, with more fruit and structure (richer, less soft, longer in the mouth).

- Rosé Champagne is pink in colour, and made by blending white Champagne with still red wine, or by maceration. Tends to be fruitier.

It is also possible to define Champagne based on how the producer sources their grapes and how they make their wine. These categories are formally defined by the Comité Champagne and appear on the Champagne label, typically in tiny print.

- NM – Négociant-Manipulant means a producer who buys grapes, must, or finished base wine from other growers and then produces and markets Champagne under their own label. Most of the large Champagne houses fall into this category, because they may own some vineyards, but they rely heavily on outside growers.

- RM – Récoltant-Manipulant is a grower who produces Champagne from grapes they grow themselves, on their own land. These producers are usually smaller in scale, more terroir-specific, and sometimes more experimental or expressive.

- CM – Coopérative de Manipulation is a co-operative that pools grapes from its member growers to produce and sell Champagne under a shared label.

- RC – Récoltant-Coopérateur is a grower who sends their grapes to a co-op to be made into Champagne, and then sells that Champagne under their own private label. The grower does not make the wine itself, but markets it independently.

- SR – Société de Récoltants is a group of growers (often a family) who jointly own and operate a Champagne-producing company. So they grow their own grapes and make their own wine. This is similar to RM but with shared resources.

- MA – Marque d’Acheteur (Buyer’s Own Brand) is a private label Champagne, commissioned and branded by a retailer or other third party. So the wine is produced by someone else (often an NM or CM) but bottled under the buyer’s brand (e.g. supermarket brands, airlines, etc.).

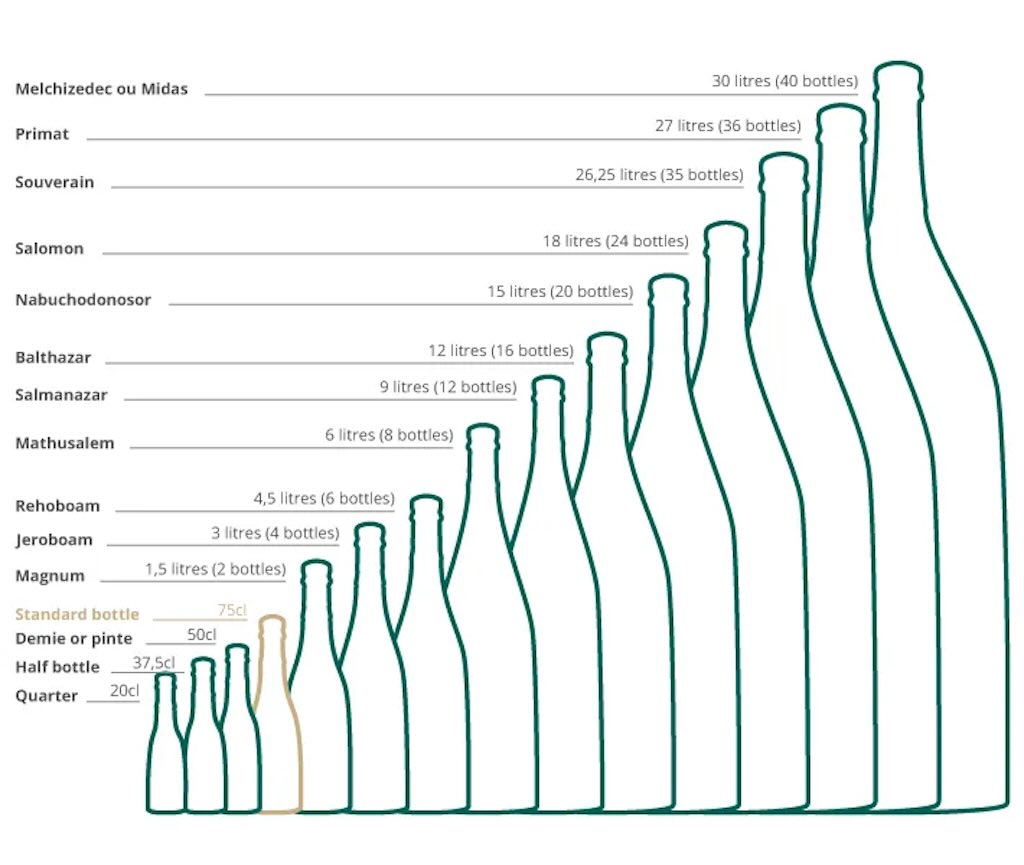

Another topic mentioned throughout the tour was the preference for the magnum over the classical Champagne bottle.

Obviously this brings up the whole issue of wine bottles. There are at least a dozen standard wine bottle shapes, at least 15 standard sizes, and ~4–5 closure types (cork and alternatives) and ~5–6 glass colour variants, resulting in more than 4,000 potential types of wine bottle. However, in global commercial use, only about 50–100 combinations are widespread. Specialty and custom designs increase that number substantially.

It’s generally thought that of the main wine bottle types used today, the Burgundy bottle, came first. It was invented in the 19th century and was initially used for varietals such as Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. As these popular grapes spread to the rest of the world, so did the Burgundy bottle. Today most red wines similar to Pinot Noir or whites that have spent time in oak are still bottled in the Burgundy bottle. The bottle’s curved sides may enhance the wine’s flavour and/or ageing process, but, in fact, the bottle’s curves were designed this way simply because it was easier to make. Luckily, soft-angled bottle shoulders improve vertical load strength, which is critical for the palletisation.

Shortly after the creation of the Burgundy bottle, came the Bordeaux bottle, also widely known as Claret. Cabernet, Merlot, and Sauvignon Blanc are a few of the most popular varietals to come in a Bordeaux style bottle. The Bordeaux, or Claret, bottle has more prominent shoulders towards its top and then tapers straight down for a narrow base. This design is ideal for high-speed filling and labelling lines. Since glass bottles bump into each other on the operational lines, two contact points (shoulder and heel) provide stability, preventing tipping and glass breakage, which minimises scrap.

Sparkling wine bottles are built differently than other standard bottles used to store and ship wine. These bottles contain high-pressure products, meaning the glass bottle must be strong enough to withstand the pressure and carbonation of sparkling wine. Round glass bottles are the only choice, as sharp edges create weaknesses that lead to breakage. Sparkling wine bottles are built to have a deep punt for structural integrity and have a bead on the finish for either a crown cap closure or wire cage over a cork.

Bottles can have different weights, heights, and neck finishes. They also come in different colours, e.g. Antique Green used for red wine and Champagne (its a dark green with a brownish tint), Dead Leaf Green (lighter than antique green, and slightly olive-coloured), Emerald Green (e.g. used for Riesling), Champagne Green (a darker antique green), and Flint (this is a clear glass but named because early high-quality clear glass was made from flint silica, a very pure form of quartz).

Of course before the creation of the Burgundy bottle, there were a variety of other shapes, e.g. the “mallet bottle”, the “squat bottle.” the onion (a type of “shaft and globe”), the “club” or “Schlegel”, the “corset”, the “bocksbeutel“, the “clavelin“, etc.

And finally the different Champagne bottles have special names for the various sizes, including the magnum.

One thing often forgotten is the cost of the bottle. My best data is for bulk orders in France, and is €0.23 to €0.30 for a 750 ml bottle (empty of course). For the magnum it’s probably €1 to €2 per bottle, and for the 3-litre Jeroboam it’s probably €18 to €27 per bottle (when buying in bulk). A 6-litre Methuselah would cost between €36–72 per bottle (bulk price) and the very, very large bottles will exceed €300 each (still empty). Wholesale bulk pricing is typically €1–2 per liter for raw glass, but premium finishing/custom molds can increase cost significantly. And for the very large bottles, the price increases substantially because many break when being tested.

So back to the magnum, which became increasingly common in Champagne during the 1800s, especially as glassmaking improved, allowing the production of stronger bottles that could withstand the high internal pressure. However, the term “magnum” (from Latin magnus, meaning “great”) likely came into popular use only in the mid-to-late 19th century.

It’s known that houses like Louis Roederer and Pol Roger began ageing top cuvées in magnums, recognising the benefits for ageing.

There are several reasons why magnums are preferred, namely:-

- A magnum has more wine relative to the amount of oxygen in the neck of the bottle, i.e. a lower ratio of oxygen to wine compared to a standard bottle. This slows oxidation (especially after the second fermentation), allowing the Champagne to age more gracefully and develop complexity. To reach similar (or superior) levels of aromatic maturity and autolytic complexity (i.e. those bready, toasty, creamy notes), magnums often need longer ageing periods, sometimes 1–3 years longer than the same cuvée in standard bottles.

- The thicker glass and larger volume help manage the pressure of secondary fermentation better than smaller bottles. Magnums hold the same pressure (~6 atmospheres) as 750 ml bottles, but the larger volume creates different internal dynamics, which is often described as finer or more integrated.

- Larger bottles are visually impressive, associated with celebration and luxury. If you turn up to a friends’ evening with two bottles, they say thank you, twice. But with a magnum they say “Wow, let the party begin!”.

The tasting on Sunday evening

The tasting included the following Champagnes, starting with the best known type, so Brut through to a Demi Sec. I’ve described them in the order they were presented.

I have included the tasting notes as suggested by the producers or offered by experts. Most of them sound, to me, ridiculous, but I’m not an expert.

At best I could try to assess the acidity, get a whiff of something dominant, detect a degree of fruitiness, and get a feel for where it sat in my mouth and if the taste had depth and length.

At the end of the day it was all about liking, or not, one or other example, and possibly deciding that I preferred “that one” over the others. And that was “on the day”, and who knows about tomorrow.

Moët & Chandon Impérial Brut NV

This is a brut style Champagne with around 7 g/l dosage, and typical is a blend of Pinot Noir 30–40 %, Pinot Meunier 30–40 %, and Chardonnay 20–30 %. Traditional method (“méthode champenoise”) with secondary fermentation in the bottle, matured at least 24 months on lees (30 months for magnums). Composed from over 100 base wines, with 30–55 % reserve wines, to maintain house style consistency.

It’s interesting that it would appear that only recently Moët has indicated 7 g/l dosage on their website. The house reduced the dosage from around 12 g/l in the late 1990s to 9 g/l, and they have only recently reduced it again to 7 g/l. Firstly, there is a broad market trend away from sweeter Champagnes toward fresher, crisper styles. And today it would appear that younger consumers seek more “precision” and “minerality”, and we should not forget that lower sugar levels appeal to wellness-aware buyers. It has also been mentioned that now grapes are riper at harvest, reducing the need to mask high acidity with dosage. It’s also possible that lower dosage allows greater expression of terroir, especially as Moët has recently emphasised vineyard practices and reserve wines. A 7 g/l dosage lets the complexity of base wines come through more clearly.

This shift is part of a strategic house-wide shift toward fresher, drier, and more terroir-expressive Champagnes. For example, the Rosé Impérial is now typically 7-8 g/l, and the Grand Vintage (White & Rosé) is around 5-6 g/l, and can drop as low as 3-4 g/l. However, this change has not affected Ice Impérial & Ice Rosé nor Nectar Impérial / Nectar Impérial Rosé.

Moët & Chandon is a NM (négociant-manipulant), and the largest Champagne house by volume. Founded in 1743 by Claude Moët, it is part of the LVMH group since 1987 (LVMH also own Veuve Clicquot, Ruinart, Dom Pérignon, and Mercier). Moët owns ~1,190 ha of vineyards, spread over 200 villages, but only about 25 % of the grapes come from its own vineyards. Its annual production is ~28 million bottles, with Brut Impérial as its flagship NV (~2 million cases annually, 6 bottles/case).

According to Moët & Chandon’s own archives and 19th-century French memoirs, officers in Napoleon’s hussar regiments, many of whom accompanied him to Épernay, began lopping the tops off Moët bottles with their sabres as they rode off in triumph, i.e. “sabrage“. Moët was so intertwined with these ritual celebrations that the practice became legendary, and associated forever with military bravado and luxury. Not independently verified, but plausible.

Although Moët now markets its flagship Moët Impérial as a tribute to Napoleon Bonaparte, historical evidence from early 19th-century ledgers and diplomatic correspondence suggests the first use of “Impérial” in connection with Moët may have originally referenced the Russian Imperial Court, not the French one.

They also once installed polished metal or mirrored panels in a small section of the Épernay cellars in the mid-to-late 1800s. The idea wasn’t to affect the wine chemically for Champagne must always be aged in the dark, but rather to explore the psychological impact on workers and visiting dignitaries. The light of a single oil lamp, multiplied by reflection, created a surreal, glowing aura around the bottles stacked in rows. The trial was apparently inspired by Romantic notions of luminosity and mystique, possibly influenced by stage illusion techniques and the fashion for “phantasmagoria” (early visual spectacles), however the experiment was abandoned quietly, as humidity ruined the reflective surfaces and mold crept in.

Moët’s own tasting notes stress the golden straw-yellow hue with green highlights, and the presence of a “vibrant intensity” of green apple and citrus fruit. They go on to mention the “freshness of mineral nuances and white flowers”, and the elegance of “blond notes (brioche, cereal, fresh nuts)”. Others have added pear, white peach tied to brioche/toasty lees undertones, and even lemon curd and “subtle smoky/mineral nuances” are mentioned.

Our wine expert Jonathan Rey stressed two particularly important points.

The first is the degree of professionalism in Moët. They have mastered blending across vintages which ensures a familiar yet high-quality tasting experience. This is because they both keep, and use, up to 55% of reserve wines to ensure depth and complexity. Whilst producing 28 million bottles, they still remain highly selective in sourcing a significant quality of fruit from other estate-growers. Many attribute this to the cellar master Benoît Gouez. I might add that Moët works hard to ensure it’s the preferred Champagne for historic events (e.g. F1 podiums comes to mind).

The second point is perhaps more important when standing in front of a selection of wines. If you want to buy a top French wine, you almost certainly have to consider purchasing it before it is bottled and released, essentially while it’s still ageing in the barrel. This means that you’re buying based on early critic scores, barrel tastings, and producer reputation, and you will usually receive the bottled wine only 18-24 months after the purchase. On top of the wine price you will still have to pay duty/transport/taxes. Through this route the buyer expects to pay a lower price than the future retail price, and, who knows, it might gain critical acclaim post-release, and the retail price may jump up. In some cases it’s nearly impossible to find the wines in retail, and buying direct from the château minimises fraud risk and should ensure perfect storage.

But given the inflated prices often seen today it not sure that en primeur is really cheaper. Rey quite rightly noted that buying Champagne, you take all the risks out of the purchase. Moët has done all the work, taken all the risks, and has put a high-quality finished product on the shelf in front of you. All you have to do is buy it and drink it.

2018 Palmer & Co Blanc de Blancs

This wine does not actually appear on the producers website. It is neither a normal blanc de blancs, yet it is not yet a collectors blanc de blancs.

Just as a reminder a blanc de blancs means a sparkling wine produced exclusively with white grapes, and for Champagne this means 100% Chardonnay grapes.

And a vintage Champagne is made only from grapes grown and harvested in a single, specified year. A vintage (millésimé) must be made 100% from grapes harvested in that declared year, and it must also be aged for a minimum of 3 years on lees (Palmer & Co typically exceeds this).

What’s so important about these “lees”? Lees are the dead yeast cells and grape solids left behind after fermentation. In Champagne and other sparkling wines, lees primarily refer to the spent yeast from the second fermentation in the bottle (the prise de mousse stage, which creates the bubbles). The lees interact with the wine over time, releasing compounds that shape aroma, texture, and taste. Lees are eventually removed via riddling (remuage) and disgorgement (dégorgement), after ageing is complete.

So this blanc de blancs is 100 % Chardonnay, sourced from Premier Cru vineyards in Montagne de Reims (Trépail, Villers‑Marmery) and Côte de Sézanne, and with a dosage of 6–7 g/l. The Vintage bottles rest 5 years on lees (exceeding the 3-year legal minimum), and for the magnums its 8 years.

This specific blanc de blancs underwent 100 % malolactic fermentation, a distinctive choice designed to add richness and softness. Malolactic fermentation is a secondary fermentation process in which malic acid (the sharp acid found in green apples) is converted by lactic acid bacteria into lactic acid (a softer, creamier acid like in yogurt). It does not produce alcohol, but it modifies the wine’s acidity and mouthfeel. So Palmer & Co intentionally allowed full malolactic fermentation in this 2018 vintage Blanc de Blancs. It would appear that 2018 was a warm, generous vintage in Champagne, and grapes reached good maturity. However, to avoid a certain heaviness and preserve the finesse in a Chardonnay-only wine, they decided to allow this fermentation in order to soften without sweetening the wine.

Palmer & Co is a grower‑producer cooperative founded in 1947, and based in Reims. It collaborates with around 350 growers, controlling over 4,000 ha across Champagne, including 200 ha of Premier and Grand Cru in Montagne de Reims. We tasted this wine in 2025, but the drinking window is projected for 2032 to 2038, suggesting good ageing potential.

Tasting notes tells us that this blanc de blancs has an aroma of subtle citrus, white flowers, almonds, with hints of white peach and lemon curd. It is medium-to-full-bodied with a silky texture, balanced racy acidity, and layers of minerality typical of chalk soils. Flavours include crunchy white peach, lemon, toast, hazelnut, and a gently saline “sea-spray” quality, with a long, clean finish.

It’s been argued that this blanc de blancs is a “showcase for Chardonnay”.

Palmer & Co. is known that for their rarest vintages (1976, 1979, 1985, 1987, 1989) they age the bottles “sur pointe” (upside-down) for 20 years or more in their chalk caves. This unorthodox practice keeps the cork moist, ensures ultra-slow development, and gives the wine a freshness and complexity even after two decades. They’re are also among the very few Champagne houses still bottling in the immense Nebuchadnezzar format (15 litres or 20 standard bottles).

Billecart-Salmon Le Blanc de Blancs Grand Cru

This wine is a non-vintage cuvée composed entirely of Chardonnay, sourced exclusively from Grand Cru villages in the Côte des Blancs, notably Avize, Chouilly, Cramant, and Mesnil-sur-Oger. The wine is vinified using the traditional Champagne method, aged on lees for approximately 48–60 months, and given a dosage of under 7 g/l.

Founded in 1818 in Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, Billecart-Salmon remains one of the few family-owned Champagne houses, and is now in its seventh generation (it is a négociant‑manipulant). They produce annually around 1.75–2.5 million bottles, and their 2020 revenue was ~€64.6 million, with a net income of ~€6.7 million.

This Champagne house has long focused on finesse over power, with a cellar philosophy emphasising precision, extended lees ageing, and temperature-controlled slow fermentation, a technique introduced in the 1950s, when it was virtually unheard of in Champagne.

What does “temperature-controlled slow fermentation” mean? It’s when the fermentation process (when yeast converts sugar into alcohol) is kept at a low and stable temperature, typically around 12–14°C. What this does is to preserve delicate aromatic compounds and better integrated the alcohol and acidity, thus enhancing a certain freshness and purity in the wine. It also helps develop a finer mousse (the texture and effervescence of the bubbles). The fermentation lasts longer than usual, often up to 30 days, compared to the usual 7–10 days at higher temperatures.

Billecart-Salmon was one of the first Champagne houses to systematically adopt cold, slow fermentation, especially in stainless steel vats, beginning in the 1950s under Jean Roland-Billecart. At the time this innovation was a departure from traditional fermentation in warmer cellars or oak barrels. The essential point was to keep a certain aromatic freshness, rather than a richer, heavier taste.

Temperature-controlled slow fermentation is now widely used in Champagne and across the wine world, but Billecart-Salmon was a pioneer, and the way they apply it remains distinctive. Today most Champagne houses now use temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks to monitor and optimise fermentation, especially for large-scale production. Billecart-Salmon didn’t just adopt temperature control, they also slowed down the fermentation process dramatically. Many houses use temperature control mainly to avoid problems, but Billecart-Salmon uses it as a creative tool to shape their house style. Their fermentation can last up to a month, longer than typical even for other cool fermentations. Some of the top houses deliberately avoid this method, or balance it by still using oak barrels.

My understanding is that this Champagne has subtly shifted in both style and positioning (and they have a new label). The Chardonnay is harvested from plots classified as 100% Grand Cru and from relatively old vines. The estate owns ~100 ha, supplemented by fruit from ~200–300 ha across 40 crus (i.e. specific villages). The base wines are vinified in stainless steel to “preserve linearity and brightness”, but a small portion is aged in used oak barrels to build aromatic complexity. Full malolactic fermentation is permitted, aligning with the house’s aim for generosity and creamy texture while maintaining a chalk-driven acidity.

Although it is a non-vintage release, Billecart-Salmon includes 25–30% reserve wines, some aged in magnum, a labour-intensive and unusual choice. This preserves freshness and depth while allowing for subtle oxidative layering over time. The reserve program also supports house style consistency, though this cuvée is notably more terroir-driven than Billecart-Salmon’s Brut Réserve.

The dosage of <7 g/l is relatively moderate and is in line with a broader trend toward more incisive, mineral expressions of Champagne. Billecart has reduced sugar levels across many of its cuvées over the past decade. In the case of Le Blanc de Blancs, this dosage preserves a slight roundness while allowing chalky tension and citrus clarity to shine through.

Tasting notes show a pale gold colour with slow, persistent bubbles. Aromas include white flowers, citrus zest, blanched almonds, and oyster shell. On the palate, the wine reveals lemon pith, white peach, crushed stone, and fine pastry notes, with a creamy yet lifted mouthfeel and a long, saline finish.

Though often overlooked next to more market-visible Blanc de Blancs, this cuvée has developed a discreet following among sommeliers.

Penet-Chardonnet ‘Hypothesis’ Grand Cru Blanc de Noirs Extra Brut

Hypothesis is not simply a cuvée, it’s a philosophical statement from Alexandre Penet, a fifth-generation vigneron working in the northern Montagne de Reims. This 100% Pinot Noir Blanc de Noirs is drawn exclusively from Grand Cru vineyards in Verzy and Verzenay, where Penet-Chardonnet cultivates 6 hectares of vines spread across ~30 plots. Some of the vines are 30+ years old, and they are rooted in deep chalk and clay-limestone soils. Their six hectares are farmed sustainably without herbicides, synthetic fertilisers, or insecticides. This house is a true grower-producer (récoltant-manipulant), combining old-vine discipline, low yields, and natural fermentations.

Alexandre Penet, formerly a chemical engineer, took over the estate with his wife Martine Chardonnet in the early 2000s. His methodical, low-intervention approach includes avoiding systemic pesticides and leans toward organic practices, although it is not formally certified. He also makes a Crémant d’Alsace (Comte de Grimm) with his Alsatian wife Martine.

This wine is part of Penet-Chardonnet’s ‘Hypothesis’ series, designed as an experimental and highly terroir-expressive line that wants to challenge preconceived notions of what Champagne can be. Hypothesis Blanc de Noirs is produced only in select vintages, and released as Extra Brut, with a dosage typically under 3 g/l, sometimes as low as 1.5 g/l. The dosage is adjusted after exhaustive tastings to allow the terroir, not the sugar, to lead.

Fermentation is carried out with native yeasts, and full malolactic fermentation is generally blocked, preserving the acidity. Base wines are partially vinified in stainless steel, with a portion aged in oak barrels (without new wood), bringing additional textural complexity. No fining or filtration is applied. Bottles are aged on lees for 4–5 years, exceeding legal minimums and allowing time for autolytic complexity to develop.

What does it mean to “block malolactic fermentation”? Firstly, it’s a deliberate winemaking choice, and it can have a huge impact on freshness, acidity, and style. A malolactic fermentation (MLF) is a secondary fermentation that converts malic acid (sharp, green-apple-like) into lactic acid (softer, creamy). It happens after the primary alcoholic fermentation, and is carried out by lactic acid bacteria (e.g. Oenococcus oeni), which can be either naturally occurring or added by the winemaker. To block malolactic fermentation they will lower the temperature to inhibit bacteria, add sulphur dioxide to suppress microbial activity, and apply sterile filtration to remove the bacteria. This whole idea is to use slow cold fermentation and a blocked or partial blocked MLF to keep a focus on the freshness as a core taste.

And what does the phrase “No fining or filtration is applied” really mean? They are two common clarification and stabilisation steps before bottling. This is often a deliberate stylistic or philosophical choice, especially among artisan, natural, or terroir-focused winemakers. Fining is the process of adding substances to wine to bind and remove unwanted particles, such as proteins, tannins, or phenolics, that can cause haze, off-flavours, or instability. Fining agents include Bentonite (clay) which removes proteins, egg white/casein/gelatin which soften tannins, and PVPP which removes bitterness and browning compounds. After binding, the resulting complexes settle out and are removed. The advantages are that the wine is clearer, more stable, the taste is softer without aggressive tannins, and it removes bitterness or off-flavours. The downside is a potential loss of character, and some agents (e.g. egg whites) are not vegan.

Filtration is just the physically removal of suspended particles and microbes using a porous membrane. It can just removed particles or it can be sterile a remove yeast and bacteria. It makes wines clear, stable, and microbiologically safe. It prevents re-fermentation in bottle (especially in Champagne), and improves shelf stability. Some people consider that filtration make wines feel more “processed” or less alive.

So “No Fining or Filtration” just means that the wine was bottled in its natural state, without these interventions. This phrase is not commonly used by the big houses, which usually fine and/or filter if only for bottle safety (especially before the second fermentation). Some grower-producers and natural Champagne makers will not fine or filter their base wines or still wines before secondary fermentation.

Unlike many Blanc de Noirs that pursue overt fruit or power, Hypothesis is firmly rooted in this sense of freshness and chalk, its character more driven by salinity than by ripeness. Its unusually low dosage and non-MLF profile might, in other contexts, risk an excessive austerity. But Penet’s low-yield fruit and painstaking élevage produce wines of great freshness and energy.

Tasting notes mention a deeply chalk-inflected Blanc de Noirs, e.g. aromas of crushed raspberry leaf, white pepper, flint, and grapefruit zest, with hints of sour cherry and salted hazelnuts. On the palate, the wine is tense, vinous, and sapid, showing redcurrant, orange peel, green tea, and chalk dust, overlaid by a faint oxidative lift and a driving saline finish. The mousse is fine yet brisk, reinforcing the wine’s architectural frame.

The cuvée is relatively rare, with production in the low thousands of bottles per vintage, and limited distribution outside France. Though approachable now, it is built to age 5–10 years in cellar and should reveal nuances of saffron, tobacco leaf, and dry spice.

Rare for the region, Penet‑Chardonnet includes vintage year, disgorging date, harvest date, bottle counts, and detailed terroir info (soil, exposition, vine age, altitude, inclination) right on the back label.

Sommeliers are beginning to see Hypothesis as a benchmark in the emerging category of terroir-first, ultra-low-dosage grower Champagne. It stands apart not only in taste, but also as a kind of philosophical statement about tradition and simplicity.

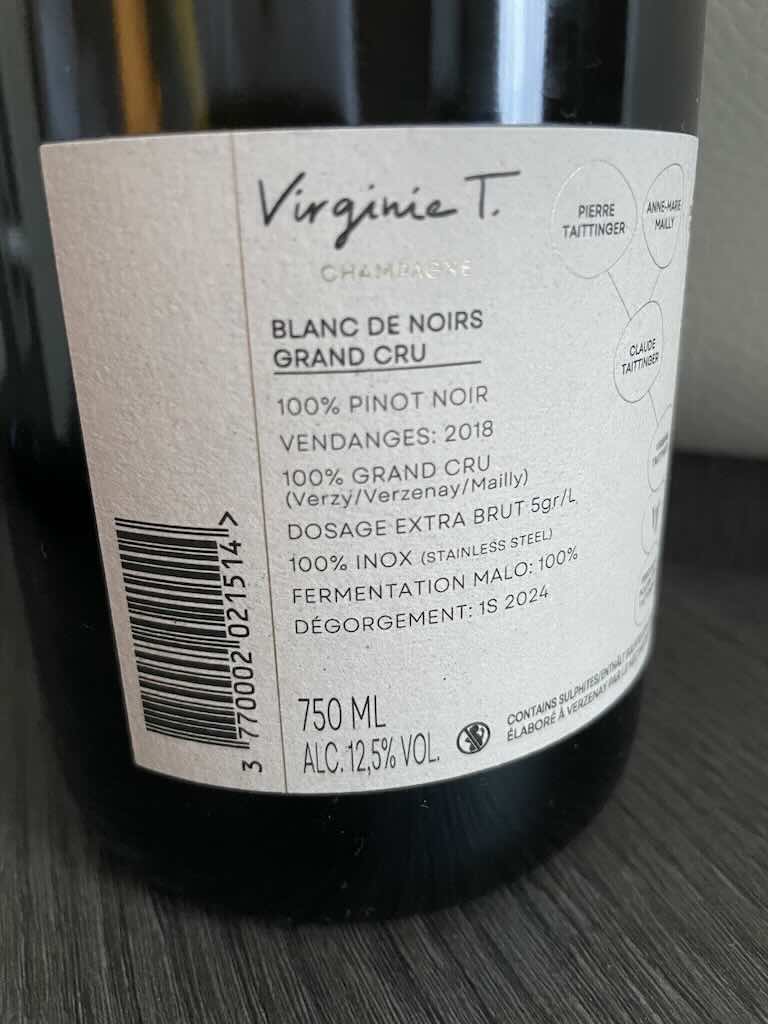

2018 Virginie T. Blanc de Noirs Grand Cru Brut

The 2018 Blanc de Noirs Grand Cru from Virginie T is a vintage Champagne that reflects a particular vision of Pinot Noir purity (but does not figure on her website). Entirely Grand Cru, 100% Pinot Noir, and made only in declared years, this cuvée is sourced from the northern reaches of the Montagne de Reims, specifically the chalky, cool-climate slopes of Mailly-Champagne, Verzenay, and Verzy. These vineyards are among the most prestigious in Champagne for structured, age-worthy Pinot Noir.

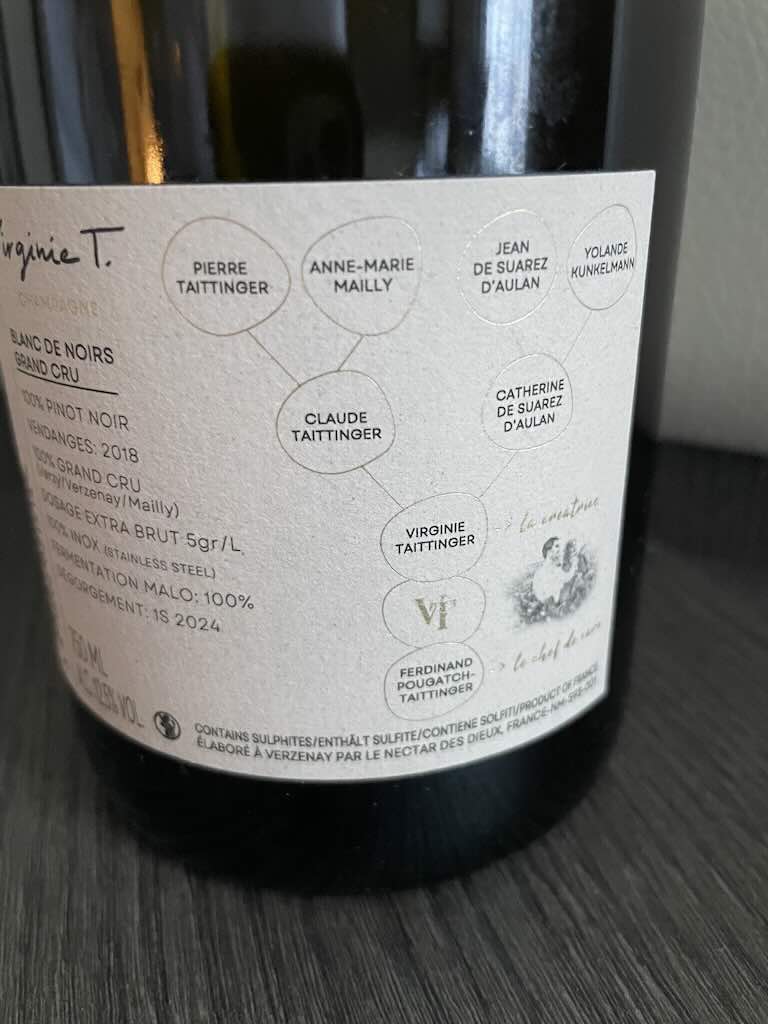

Virginie T is the project of Virginie Taittinger, daughter of Claude Taittinger. She founded the house after departing Taittinger Champagne in 2006. While the family heritage runs deep, Virginie’s own maison is independent and ambitious. She works in close partnership with her son, Ferdinand Pougatch, and the house operates as a négociant-manipulant, but with tight control over viticulture and selection. The production is deliberately small-scale, blending tradition with a modernist push toward terroir and product transparency. Production is limited and artisanal, with only ~80,000 bottles produced across all cuvées, with this Blanc de Noirs production was <10,000 bottles in 2018.

The 2018 vintage was marked by record sunshine and a warm growing season. The ripeness levels were exceptional across Champagne, and for Pinot Noir in particular, the conditions offered richness and aromatic breadth. But, in the true winemaking tradition, care was needed to avoid over-extraction or loss of the interplay between acidity, minerality, and structure. Virginie T opted for complete vinification in stainless steel to retain fruit clarity and freshness. Full malolactic fermentation was allowed, to soften the naturally firm Montagne acidity and integrate the ripe fruit profile.

The wine aged 4 years on its lees, well beyond the legal minimum, and was released with a Brut dosage of <6 g/l, a stylistic midpoint that balances fruit generosity with a dry, incisive finish. No oak was used in this vintage, and no bâtonnage (lees stirring), allowing the Pinot Noir to show its aromatic side rather than leaning into oxidative or creamy textures.

Tasting notes for this wine highlight aromas of ripe orchard fruits (pear skin, mirabelle plum), along with dried rose petal, hazelnut, and a touch of its chalk terroir. On the palate, the wine is generous but structured, with flavours of wild strawberry, red apple skin, white pepper, and brioche, supported by a fine-bubbled mousse and a chalk-dry finish.

Virginie T positions this cuvée as a kind of “modern classic respectful of Champagne tradition but stripped of excess”.

It’s important to understand the timeline of Virginie Tattinger, if only to understand her desire to protect what she sees as a mix of tradition and art. She was one of nine children of Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger, and she worked for more than 20 years on the maison’s image and promotion.

in 2005 the Taittinger family sold the Taittinger Group (including the Champagne house and the hotel empire Société du Louvre) to Starwood Capital, a US private equity firm. Virginie saw this as a loss of the family legacy, and in 2006 she was dismissed from the house (as they say “let go”).

But also in 2006, with backing from Crédit Agricole du Nord Est, Pierre-Emmanuel reacquired the Champagne arm of the business from Starwood. The house is now effectively under family control again, with Crédit Agricole retaining an investment stake. But Virginie was not invited back. So in 2008 Virginie filed the trademark for “Virginie T”, and launched a completely independent maison.

This Champagne has an unusually complete label, and we will discuss this below.

These two images of the Virginie T. Champagne label show a bottle that is not just transparent in its winemaking, but unusually forthright in disclosing details that are rarely found on a Champagne label, even among grower-producers or so-called “haute couture” cuvées.

Most labels would stop at “Grand Cru” or name a single village. Listing three specific Grand Cru villagesis a rare level of disclosure and implies a deliberate expression of terroir blend.

Vintage Champagnes typically carry the vintage, but not always the harvest year (“vendanges”) or a disgorgement date. The disgorgement listed as “1S 2024” (likely “1er semestre 2024”) is highly unusual in its precise timing. This allows consumers to calculate time on lees (approx. 5–6 years), which is a detail connoisseurs crave but is often missing.

While “Extra Brut” is increasingly used, disclosing the exact grams/liter is rare and adds technical honesty.

Most Champagne houses keep vinification practices vague. Here, we get clear confirmation, no oak, and full malolactic fermentation. This gives strong insight into the intended profile, i.e. rounder mouthfeel.

One of the most distinctive and virtually unheard-of features is the family tree or lineage diagram printed on the label. It maps Virginie Taittinger’s ancestry, showing her descent from both the Taittinger and Suarez d’Aulan families, making it a dynastic wine declaration, akin to noble bloodlines, but for Champagne heritage. It ends with her son Ferdinand Pougatch-Taittinger, who is identified as “le chef de cave”. Again, it is extremely rare to name the cellar master on a label, let alone in a multigenerational narrative arc. It’s a dynasty-in-a-bottle concept.

Lanson Le Rosé – Création 67 Brut

This is a non-vintage brut rosé Champagne, part of the maison’s recently reformulated “Le Collection Création” series. The number 67 refers not to the year but to the 67th edition of this house rosé blend, part of a deliberately numbered series that emphasises continuity, transparency, and the reserve wine program behind each release. With the Création line, Lanson offers a modern take on their historic cuvées, while also restoring their distinctive, non-malolactic, bright-fruit house style.

This multi-vintage rosé is composed of roughly 53% Pinot Noir, 32% Chardonnay, and 15% Meunier, including 7% still red wine, mainly from Bouzy and Les Riceys, two Pinot Noir terroirs famous for depth and colour. The red wine component is critical here, as Lanson does not use rosé saignée (bleeding) but rather a blending method that allows for more precise colour and aromatic control.

Rosé saignée (“bleeding”) is a method of making rosé wine by “bleeding off” some of the juice from red wine fermentation after a short period of skin contact. It is primarily used in red wine regions to concentrate the remaining red wine, while also producing a rosé as a by-product, though high-end rosés can also be made intentionally by this method. So red wine grapes (like Pinot Noir) are crushed, and the juice is left to macerate with the skins. After a short time, usually a few hours to a day, depending on the desired rosé colour, some of the pale pink juice is “bled off”. The removed juice is then fermented separately as a rosé wine.

The saignée method is used in rosé Champagne, but it is less common than the blending method. The most common method involves a small percentage (typically 5–20%) of still red Pinot Noir or Meunier wine being blended into the white base wine before secondary fermentation. This method is legal in Champagne, unlike for still wines in most of the EU.

Création 67 is aged for a minimum of 4 years on lees, and includes an unusually high 35%–40% of reserve wines, some over 20 years old, selected from Lanson’s perpetual reserve system (solera-like in concept). Dosage is 7 g/l, bringing balance and roundness while respecting the dry, high-tension backbone typical of Lanson’s vinification philosophy.

“Solera-like in concept” means uses a system or process similar in principle to the “solera method”, but not necessarily following the strict traditional structure of a solera. The solera system is a traditional ageing method, most famously used in Sherry (from Jerez de la Frontera, Spain), but also found in some balsamic vinegars, rums, Madeiras, and even some modern beers or wines. It involves a fractional blending across vintages or batches. Traditionally there is a system of stacked barrels or containers arranged in tiers. The newest product added at the top, oldest drawn from the bottom (the actual “solera” row). Each year, a portion is drawn from the oldest row for bottling, and replaced by the next oldest, and so on up the chain. This creates a continuous, consistent product that integrates small amounts of very old material into each bottling, a kind of “perpetual blend.” A Champagne house may keep a perpetual reserve wine in a single tank or “foudre” (French term for a large cask of indefinite size), topping it up each year with new wine.

What truly sets this cuvée, and the entire Création range, apart is that Lanson blocks malolactic fermentation in all base wines, preserving sharp malic acidity. This deliberate choice hearkens back to the house’s pre-WWII practices, reinstated in the 1970s and continued today. Blocking malo in rosé is relatively uncommon, and it yields a wine of piercing freshness, and long ageing potential, even in non-vintage form.

Lanson, founded in 1760 and one of the oldest Champagne houses, is based in Reims. While historically part of the LVMH group, it is now owned by the Boizel Chanoine Champagne Group (BCC). The house commands more than 50 hectares of its own vineyards and purchases from a wide network of growers, especially in Verzenay, Avize, and the Vallée de la Marne. The house produces around 4–4.5 million bottles annually. Lanson remains one of the few Grandes Marques to hold fast to traditional, non-malo vinification across its entire range.

Lanson’s historic ties to the British Royal Family go beyond the usual Royal Warrant. In the early 1900s, Lanson kept a specific rosé blend that was only served at Buckingham Palace garden parties, and nowhere else. However, even the cuvée name has been lost, and no labels survive.

Tasting reveals a vivid salmon-pink robe with copper glints. The nose offers a perfumed burst of wild strawberry, redcurrant, and pomegranate, lifted by floral hints of hibiscus and pink rose. Subtler notes of sanguine orange, crushed mint, and chalk emerge with air. On the palate, Création 67 is energetic and linear, with flavours of blood orange, white cherry, rhubarb, and a touch of ginger biscuit. The mousse is fine, brisk, and persistent, with a racy acidity and a stony, grapefruit-zest finish.

Unlike many NV rosés that lean on creamy softness or overt sweetness, this rosé stands apart for its architectural freshness and its gastronomic ambition. This is a rosé Champagne with backbone.

This is a cuvée that discreetly preserves a historic style of Champagne. It’s sweeter, more voluptuous, and unapologetically generous. Once the dominant style in the 19th century, demi-sec today occupies a more selective niche, much appreciated by pâtissiers. This non-vintage blend offers a contemporary revival of that tradition, focussed on craftsmanship and marked by restraint rather than excess.

The blend mirrors that of the house Brut Réserve NV, with around 33% each Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, and Chardonnay, drawn from over 30 crus, predominantly from Grand and Premier Cru vineyards in the Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, and Côte des Blancs. The base wine typically includes 25%–30% reserve wines to ensure depth, complexity, and continuity of style.

The key distinction, of course, lies in the dosage. Rich Demi-Sec is finished with a dosage of approximately 34 g/l, placing it at the upper end of the demi-sec category. Yet the base wine is vinified with such balance, freshness, and acidity that the sugar is not dominant, but rather supports the wine’s structure and length rather than masking it. Full malolactic fermentation is permitted, softening acidity and contributing to the wine’s creamy texture.

The wine is aged on lees for 4 years before disgorgement, longer than the legal minimum. Bottles are rested post-disgorgement for several months before release to allow the dosage to fully integrate into the wine’s texture.

Pol Roger, founded in Épernay in 1849, remains one of the few grandes marques still family-owned and operated. Its house style is classically balanced and elegant, with a preference for clean ferments, long lees ageing, and deliberate reserve blending. Winston Churchill, one of the house’s most famous devotees, preferred the richer, more mature styles that this demi-sec evokes. After WWII, Pol Roger supplied to Churchill a Champagne aged even longer than the commercial releases. These bottles were sent unlabeled, held longer sur latte, and included in shipments that were never entered into public or trade ledgers.

Pol Roger is part of the “Primum Familiae Vini” group.

On February 23, 1900, Pol Roger’s main cellars in Épernay suffered a massive collapse. An estimated 1.5 million bottles and 500 casks of Champagne were buried under rubble and earth, a loss so severe that it nearly bankrupted the house. In rebuilding, Pol Roger dug down to 33 metres, and developed a multi-level network of chalk tunnels that are exceptionally cold with an average of 8.5°C, versus the 10–12°C typical elsewhere. This lower temperature leads to slower secondary fermentation and longer, gentler ageing on lees, which contributes to the famously creamy yet tightly structured Pol Roger style. It also helps preserve freshness in reserve wines, making them less reliant on blending tricks. Experts occasionally mention these cellars as “Pol Roger’s underground fridge”.

Despite its name, Rich is not ostentatious. Tasting reveals a golden straw colour with persistent, delicate bubbles. Aromas suggest baked orchard fruit (pear Tarte Tatin, spiced apple), along with acacia honey, almond cream, and toasted brioche. On the palate, it is opulent yet fresh, with flavours of quince paste, lemon curd, nougat, and crushed hazelnuts, all buoyed by a soft but present acidity.

It goes very well with blue cheeses like Roquefort or Fourme d’Ambert, or even with spicy Asian dishes, where the sugar balances heat and salt. Unlike most Brut Champagnes, this can also benefit from slight chilling (7–8°C) to sharpen its profile.

In a world increasingly dominated by ultra-brut and zero-dosage, Pol Roger Rich is a rare reminder that sugar, when balanced, is not a flaw but a form of generosity, and a throwback to another era, executed with modern finesse.

This tasting session was in many ways an eye-opener

During COVID my wife and I tried around 60 Champagne (many rosé and even a few cavas). I certainly didn’t bother with tasting notes but we finally settled on Gosset rosé.

Now after this tour, including the above tastings and the later visits, I’m trying to breakdown what I’m thinking, or is it “supposed to think”?

Overall, I think that Jonathan Ray, our wine expert for this tour, did a good job. I would have personally preferred a far more scientific focus, as per the title of the tour. “Tasting Champagne” would have been a more honest title for the tour, but I appreciate it might not have attracted many punters.

I liked that he focussed on offering a larger variety of tastings, yet focused in on character, terroir, and authenticity over brand glitz. I suspect he prefers well-crafted acidity with a bit of mineral tension. I’m not sure he is a fan of non-MLF wines. And I detected a leaning away from mainstream (mass-market) brands and celebrity-endorsed novelty wines, and towards smaller terroir-driven craft houses using a mix of modern/traditional methods. I also think he knows that a bit of “bling-authoring” sells books and articles in The Spectator.

My comments:-

Firstly, the language used in tasting notes is idiotic (or worse). Do they inform? No! Do they hide one or two really useful comments in an overgrown “rain forest” of pretentious clichés? Yes! Someone said that the truly useful comment is like a truffle hidden in the undergrowth. Technically it’s there, but you need to be a trained pig to find it. I’m in my 70s, I don’t have time to waste on understanding “notes of crushed oyster shell, gooseberry, or wet chalk”.

Secondly, I was amazed during the early tasting to find that it was very difficult to decided what I didn’t like. I would happily drink any one of the wines, and I actually decided I preferred a brut nature style Champagne. This surprised me, but I’m sure if I tasted the same wines on a different day, or with food, or standing on a ship’s deck in the Arctic, I would have a different opinion.

Setting aside the emotional charge that drinking Gosset Champagne, the favourite wine of my beloved wife, gave me. My third comment involves the incredible variation that Gosset offered us. In the on-site visits, there were differences between their different wines, but I’m not sure I would be able to do much more than differentiate them based on colour, acidity, and possible length in mouth. Yet Gosset blew me away. Each of their wines had a uniquely different mouthfeel, there was a distinct “taste canyon” between each wine. It sold me on non-MLF wines.

This in itself was sufficient justification for the tour, I didn’t really know what malolactic fermentation (MLF) was, and what it meant in terms of vinification tradition. Now I know the difference, and I will spend the rest of my life appreciating it (or its absence).

Finally, I also found out that I like Pinot Noir, but not when it’s clumsy or too earthy. I like when the acidity, fruitiness, and depth work together. I also found out, or confirmed, that I’m not that impressed with blanc de blancs. I just found the ones I tried a bit “one-dimensional”. Why pick a blanc de blancs, when I could drink a Gosset rosé?

La Grande Georgette Restaurant

After the tasting, the group meandered over to La Grande Georgette Restaurant.

We took the “Menu en 4 Séquences – 75€“, which included:-

Asperge blanche de Mairy-sur-Marne – Condiment d’amandes iodées (White asparagus from Mairy-sur-Marne – Iodized almond condiment)

Sandre en quenelle – Extraction de petits pois (Pike fish quenelle – Peas extraction)

Longe de veau fermière – Consommé aux essences de verveine (Veal loin – Verbena consommé)

La pistache croustillante – Emulsion vanille (Crispy pistachio – vanilla emulsion)

The wines were selected by Jonathan Rey, and were:-

- 2022 Julien Pilon Crozes Hermitage Blanc “On the Rhône Again”

- 2017 Trimbach Pinot Noir Réserve

The atmosphere was interesting and food excellent, but a round table for eight would have been better.

Monday 09 June

On the Monday morning we visited the small champagne house of Henri Chauvet, where we had a tasting with owner Damien Chauvet. They are situated in Rilly-la-Montagne, a commune in the Marne department, in the Grand Est region of north-eastern France. It lies approximately 10 km south of Reims, on the northern edge of the Montagne de Reims, a prominent plateau that is central to Champagne viticulture. The commune consists of about 880 hectares, of which around 310 are vineyards and 350 forests. The entire commune of Rilly‑la‑Montagne is classified as Premier Cru Champagne, and there are approximately 38 Champagne-producing wineries (winegrowers/maisons) active in the commune.

The villages name appears in historical records as early as the 9th century, and later its vineyards were tied to the powerful Benedictine monasteries of Saint-Rémi (Reims) and Saint-Thierry. In the early 1850s, construction began on the 3.5 km railway tunnel between Rilly and Germaine (now a small rural commune), dramatically improving transport links between Reims and Épernay. But this also enabled growers to carve chalk cellars beneath the commune. During World War II, the village’s railway tunnel was repurposed by German forces for the storage and assembly of V-1 flying bombs. The site was targeted and bombed by Allied forces in 1944, marking a significant event in the village’s history.

Rilly-la-Montagne is classified a Champagne Premier Cru village, which is a significant designation within the Champagne Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) system. In Champagne classification, vineyards are rated by their quality potential, starting with Grand Cru (100%), then Premier Cru (90–99%), and finally Autre Cru (below 90%). Rilly-la-Montagne vineyards are typically rated at 94–95%, placing them in the high tier of Premier Cru villages.

The 100%, 90%, etc. scores refer to the Échelle des Crus (“ladder of growth”), a historical classification system unique to the Champagne region. The Échelle des Crus was introduced in the early 20th century (officially codified in 1911) as a way to classify Champagne villages (not individual vineyards) based on the perceived quality of their grapes.

Each wine-growing village (commune) was assigned a percentage score between 80% and 100%. The score determined the price the growers could be paid for their grapes relative to a set base rate. So if a village like Rilly-la-Montagne was rated at 95%, its growers could be paid 95% of the maximum price per kilogram of grapes. The system was abolished for pricing purposes in 2003, but it is still widely used as a qualitative marker in labelling and marketing, especially for grower-producers. So a Champagne labeled as “Premier Cru – Rilly-la-Montagne” means the grapes came from vineyards within the commune of Rilly-la-Montagne, which is historically rated around 94–95% on the Échelle des Crus.

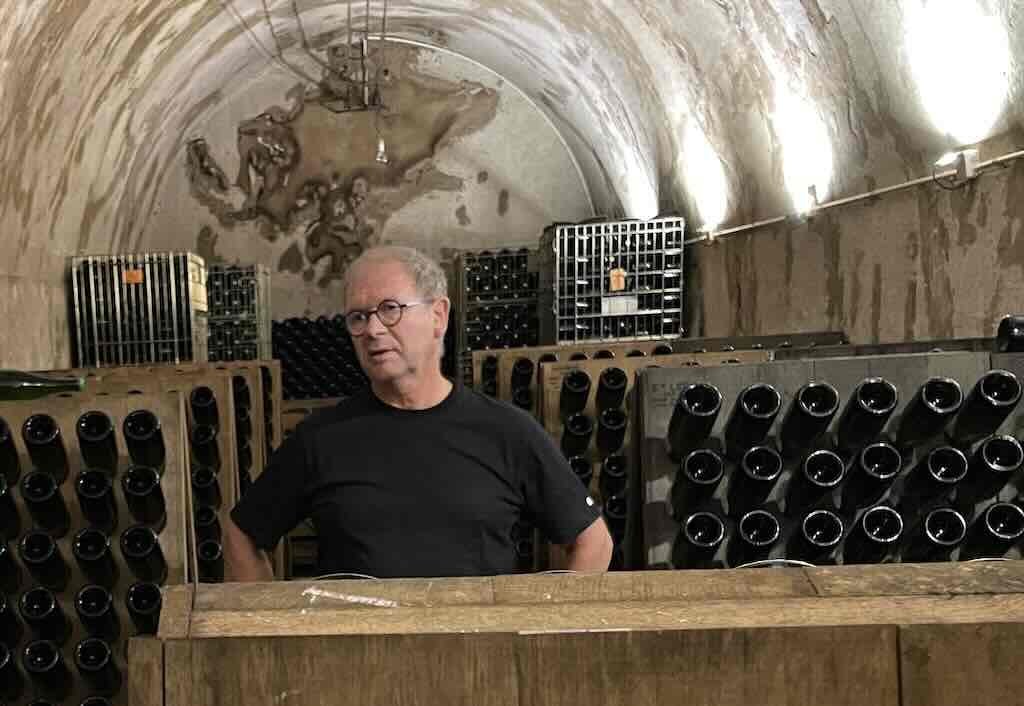

Champagne Henri Chauvet is a family‑run grower‑producer (Récoltant‑Manipulant) founded in 1890 by Henri Chauvet, and now managed by the 4th generation, Damien and Mathilde Chauvet. I understand that Henri Chauvet was originally a viticulteur et pépiniériste, meaning he grew vines and specialised in grafting new plants. He established his estate in Rilly‑la‑Montagne shortly after the phylloxera crisis had devastated Champagne’s vineyards.

Today the estate cultivates approximately 8.2 hectares of vines, 60% Pinot Noirs, 10% Meunier, 30% Chardonnay. They proudly claim to be independent, controlling everything from vineyard to bottling, “de l’entretien et la vendange jusqu’à l’assemblage et l’étiquetage en propre”. They also claim a strong commitment to tradition, by using indigenous yeasts, and long lees ageing in old vaulted cellars. The entire operation is HVE-certified (“Haute Valeur Environnementale”) and they qualify as a vigneron indépendant.

HVE-certified, established in 2012, is a French agricultural certification awarded to farms and vineyards that meet high standards for environmentally respectful practices. It’s awarded to farms that demonstrate sustainable practices across four key environmental areas:-

- Biodiversity Conservation means maintaining natural assets such as hedgerows, grass strips, trees, flowers, insects, birds. It also stresses avoiding monoculture, and encouraging ecological corridors and habitat diversity.

- Plant Protection Strategy means limiting pesticide use, using integrated pest management, and favouring mechanical or biological methods over chemicals.

- Fertiliser Management means reducing the use of nitrogen and phosphorus, and avoiding leaching and groundwater contamination.

- Water Management means minimising irrigation, monitoring water usage, and preventing pollution of waterways.

In the wine sector, HVE certification means that the entire vineyard estate must be managed sustainably. It is not organic, but can overlap or complement organic or biodynamic farming. HVE does not ban synthetic chemicals, but it promotes reduction.

The expression “vigneron indépendant“ has a very specific meaning, and in many ways it defines who Damien and Mathilde Chauvet are, and what their values are as a grower‑producer (Récoltant‑Manipulant). Firstly, they are governed by membership in the French national association of independent winegrowers, the Vignerons Indépendants de France (VIF).

It means they grow their own grapes, on land they own or lease. They don’t purchase grapes. They harvest and vinify their own wine, on their own estate or under their control, using grapes from their own plots. They bottle under their own label, and it’s marketed under the vigneron’s name (not under a larger brand or co-operative). This means they don’t buy grapes from multiple sources, don’t participate in a co-operative of growers making wine collectively, and they sell exclusively under their own label.

This means they tend to use artisan techniques, to produce wines with traceable origin (“grape-to-bottle” by one person or family). And the wine should reflect a very specific terroir, rather than a blended house style.

What does it mean to be a grower‑producer? Firstly, the entire “house” consists of five people, the husband and wife owners, plus three other full-time workers. In addition they use up to 20 seasonal vendangeurs. Secondly, production is directly limited by the land owned or leased. Production was 73,000 bottles/year, but all Champagne producers must now reduce production.

For the 2024 harvest, the Comité Champagne (CIVC) mandated a maximum yield of 10,000 kg/ha, down from 11,400 kg/ha in 2023 and 12,000 kg/ha in 2022. The official rationale for the reduction in production across Champagne is primarily based on a combination of market demand management and inventory control, not on quality concerns.

Champagne exports declined by about 15% in 2023–2024, and domestic sales in France are also down sharply. In addition, Champagne stock levels reached the equivalent of 4 years of sales, which is above the ideal inventory buffer (usually 3 years). This means that Chauvet will be forced to reduce production, and this may be why he mentioned that he would be leasing an addition 0.5 hectares. This would meant that he could more or less maintain his production at a stable level.

We first visited “le cave“, 10 metres underground, which date from 1892, and can store up to 220,000 bottles. Here the temperature is a constant 10°C, and they still perform the remuage manually. There is a second cellar 5 metres deep, and built in 1983, used for storing bottles before shipping.

It was interesting to note that experts might discuss the advantages of cellars cut into chalk, but the owner Damien Chauvet didn’t consider it important as compared to the maintenance of a constant cool temperature for storage. In fact, he continuously stressed that almost the only important things were the quality/maturity of the grapes and the respect of the tradition in winemaking. He often shrugged his shoulders when asked about one or other technical detail.

Looking back, it’s quite difficult to isolate what we know and don’t know about the winemaking techniques used. We know they use standard Champagne methods (tirage, secondary fermentation in-bottle). The producer claims that “fermentations alcoolique et malolactique spontanées” are performed. This means both alcoholic and malolactic fermentations occur naturally, without commercial inoculation. We also know that the wines undergo “un élevage de … environ douze mois” in barrels, without clarification on barrel type or sizes.

We don’t know the exact barrel details, such as size (barrique, demi-muid, etc.), proportion of new to used wood, and the origin of the staves. We don’t know the lees ageing duration and conditions before the second fermentation (tirage). We don’t know details on the use of dosage, the clarification method, filtration approach, or sulphite levels. We don’t know if the producer follows minimum appellation ageing rules, etc. There is a mention in secondary publications of aged on lees for a minimum of 3 years.

However, Henri Chauvet’s NV wines are consistently praised by critics and guides for their polished, traditional style, balanced blends, pleasant yeast character, and refreshing mineral finish. We have solid expert praise backed by scores and tasting descriptors.

We tasted the Brut Réserve (NV), not shown in the above photo, which is a blend of 50-50 Chardonnay/Pinot Noir, aged ≥3 years, dosage ~7 g/l. Tasting notes mention citrus, green apple, brioche, almond and toast with a medium‑body character.

The Brut Nature (Non Dosée), means no added sugar. This is a blend of ~80% Pinot Noir, ~20% Pinot Meunier. I think the house also makes a Blanc de Noirs Brut which is a 100% Pinot Noir. The Brut Nature is bone-dry, mineral-driven, more precise and austere. Tasting notes mention white stone fruit, crisp apple, and chalky minerality.

The Rosé (Cuvée Aphrodite Brut Rosé) is a blend of Chardonnay with Pinot Noir, and is an attractive salmon-pink colour. Tasting notes mention a creamy yet lively taste, combining fresh red berries with plum, cherry, and slightly peppery, with an elegant structure on the finish.

The Cuvée Adonis (2019) is a vintage Blanc de Blancs made exclusively from Chardonnay. It’s noted for its elegance and structure.

I’m not a great fan of very dry Champagne, and with my wife we always preferred a fresh, fruity rosé, but my preference here was for the Brut Nature.

Last question, are they profitable? We don’t have any publicly available figures, but we can try to guess. Starting with the facts. They have 8.2 hectares and produced in the past 73,000 bottles. They own their land, have a strong cellar-door presence, and probably have higher-margin cuvées (e.g. Adonis, Cuvée Noire, Blanche). Full-time employment is five people (including owners), and 20 seasonal workers. And we know their pricing ex-cave, which excludes packaging, shipping, wholesaler/retailer markups, import duties, etc., but includes 20% sales tax.

Firstly, the production per hectare is below the latest limit, so production normally will not be affected. Leasing another 0.5 hectares will give them more flexibility to plant new stock, etc. For an efficient producer, maintaining quality levels, we can presume a cost per bottle of around €14, with permanent staff and overheads costing up to €5 or even €6 per bottle, followed by cellar vinification costing another €3 or €4. A bottle (Brut Reserve) at the cellar door costs €17.50 ex-tax, and will be discounted for larger sales.

My guess is that their margin is modest (~15%). It’s not high, but is respectable and sustainable for a quality-focused champagne grower. A non-negligible element is the increased margins on the premium bottles (e.g. Cuvée Blanche, Noire, and Adonis), and an interesting markup for the magnum (plus €2 net).

We returned to Reims for lunch at the local brasserie, Le Boulingrin. The name actually came from the English “bowling green”, but meant at the time sunken grassy area within a formal garden lawn. “Boulingrin” was a standard term in French landscape architecture. In fact Le Boulingrin is a neighbourhood in the city that got its name from a grassy esplanade or garden laid out in the late 18th or early 19th century.

La Brasserie du Boulingrin is renowned for its traditional French cuisine and Art Deco ambiance.

I took “Vol au vent au ris veau, crème aux morilles et champignons, riz à l’étuvé” (Sweetbread vol-au-vent, morel and mushroom cream, steamed rice). Followed by a Paris-Brest, which I found a little heavy.

At 16:00 we meet a local guide from Reims tourist office for a tour of the Cathedral of Reims. It is considered a Gothic masterpiece constructed between 1211 and 1345. It served as the traditional site of the coronation of French kings from the 11th century until the 19th century, including the coronation of Charles VII in 1429 attended by Joan of Arc.

I don’t intend to present in detail this masterpiece of Gothic architecture. In fact, I was very impressed with the city in general, and I hope to return in the not too distant future.

The west façade is one of the most richly sculpted in all of Gothic architecture. It features over 2,300 statues, including biblical kings and prophets, scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary, and the famous Smiling Angel (L’Ange au sourire), whose gentle expression has become an emblem of Reims itself.

The sculptures are not merely decorative, they were designed to communicate religious stories and teachings to a largely illiterate medieval population. Each portal is crowned by intricate tympanums and filled with layered rows of saints, angels, and symbolic figures, forming a sort of stone Bible for the viewer.

Although the sculptures now appear in bare stone, they were originally painted in vivid colours (e.g. reds, blues, greens, and golds), that would have made the entire façade shimmer in sunlight. This polychromy has long since faded due to weathering and time.

To revive this lost experience, a nighttime projection show called “Rêve de Couleurs” (Dream of Colours) is often held during the summer months. Using precise light mapping, it reconstructs the original colour scheme directly onto the façade, offering a rare glimpse of how the cathedral might have looked to 13th-century eyes.

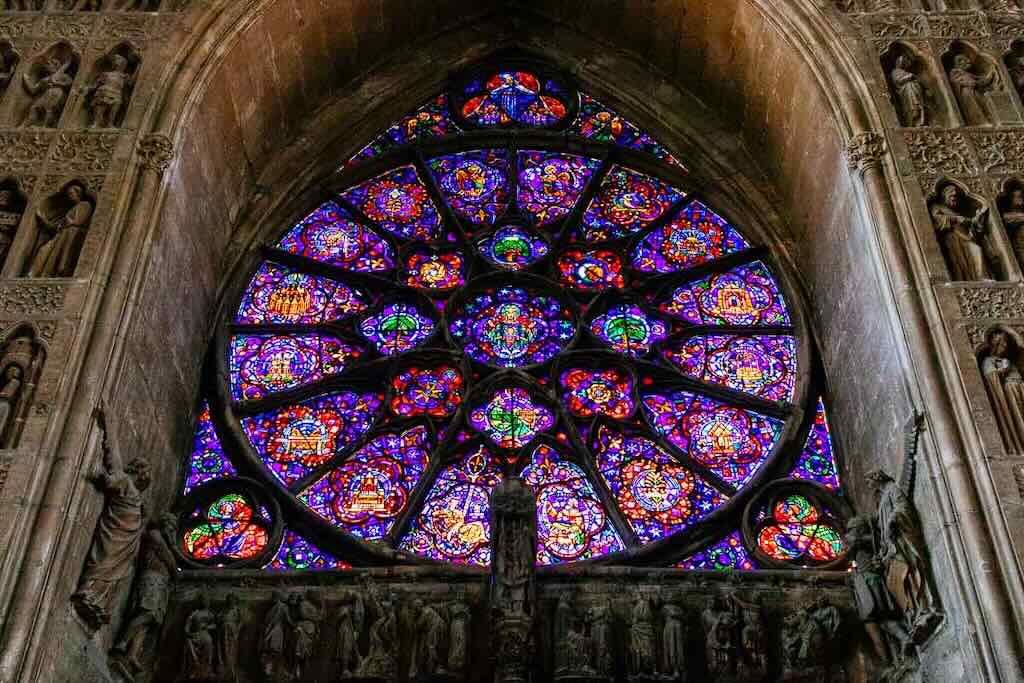

The rose window above the central portal of Reims Cathedral is a stunning example of Gothic stained glass. Dating from the 13th century, it features a radiant wheel-like design with biblical scenes at its center, framed by intricate geometric patterns. It floods the nave with coloured light and is meant to symbolise the divine order and unity of the universe.

In Reims, and some other High Gothic cathedrals, the main structural loads (i.e. the roof, vaults, and upper walls) are carried by the stone piers, arches, and especially buttresses. The window openings, including rose windows, are part of non-load-bearing infill between structural elements. This means the stone tracery within these windows serves primarily to hold the glass and divide it into manageable sections, not to bear the weight of masonry above.

At Reims, this system is refined to an exceptional degree. The west rose window, for example, sits between buttresses and is framed within a stable arch. This means that almost none of the window’s internal stone structure bears any vertical load. This allowed medieval builders to create lighter and more elaborate designs, prioritising aesthetic and theological expression over brute structural function.

The cathedral is also home to the Chagall windows, installed in 1974 in the apse. Created by artist Marc Chagall, they depict scenes from both the Old and New Testaments in his signature flowing lines and dreamlike blues, reds, and greens. These windows are a rare modern addition that blends respectfully with the medieval architecture while offering a contemporary spiritual vision.

Champagne terminology

Viticulture & Harvest

- Côte – A slope or hillside, often part of vineyard names (e.g. Côte des Blancs).

- Clos – A walled vineyard (e.g. Clos du Mesnil).

- Pressurage – The act of pressing grapes, extremely regulated in Champagne.

- Marcs – The official term for a press load of grapes in Champagne (4,000 kg max).

- Cuvée – The first, highest-quality juice (about 2,050 liters from a marc).

- Taille – The second pressing, lower in acid and quality (up to 500 liters).

Winemaking

- Débourbage – Juice clarification before fermentation.

- Vin clair – The still base wine, before secondary fermentation.

- Assemblage – The blending of different base wines (from different crus, grape varieties, or vintages).

- Tirage – The bottling of the blended wine with sugar and yeast to induce second fermentation.

- Liqueur de tirage – Mixture of sugar and yeast added before tirage.

- Prise de mousse – The “foam taking” — the second fermentation in bottle that produces the bubbles.

Aging, Riddling, and Disgorgement

- Sur lattes – Bottles stored on their sides during aging.

- Remuage – Riddling: gradually tilting and rotating bottles to collect sediment in the neck.

- Pupitre – The traditional wooden A-frame rack used for remuage.

- Gyropalette – A modern machine that automates riddling.

- Degorgement (à la volée/à la glace) – Removal of the sediment plug; manually (volée) or by freezing (glace).

- Liqueur d’expédition – The dosage: a mixture of wine and sugar added after disgorgement.