Over Christmas 2019 we decided to spend a few days relaxing in the 5-star Royal Champagne, a hotel and spa located in Champillon in France. In writing our review of the hotel we decided to also pen a short review of what we saw from the hotel terrace.

Champillon is a small village sitting between the city of Reims and the town of Épernay, so it’s situated in the heart of the Champagne region.

The view from our terrace

Having completed our review of the hotel we sat back and enjoyed the views over the valley.

Above we could see the village of Champillon nearby on the left, and in the distance we have the town of Épernay.

Just over to the right (see the below photo) we have the village of Hautvillers, the home of the famous Dom Pérignon, the Benedictine who helped develop the Champagne.

According to the ‘échelle des crus‘, established in the 18th century, there are 294 ‘crus du champagne‘ classed in three categories. There are 17 ‘Grands Crus classés‘, and there are 44 ‘Premiers Crus classes‘, including those in the village of Champillon. The remaining 237 production areas are just called ‘crus classes‘, and are only allowed to simply mention ‘Champagne‘ on their bottles. In 2017 there were 15,800 winegrowers in the Champagne region.

The idea of a ‘cru‘ is a way to designate a precise ‘vignoble‘ or piece of land or region of production. And for Champagne ‘cru‘ actually means an entire commune. The idea was to permit growers to fix a price per kilo on grapes being sold to ‘négociants‘. These buyers purchase grapes for the big Champagne houses, and according to tradition they must guarantee that the grapes they buy are ‘sain, loyal et marchand‘ (sound, fair, and marketable). The way it works is that for a given year a price is decided per kilo of grapes, then each producer receives a percentage of that price. The ‘Grands Crus classés‘ are paid 100% of that price, the ‘Premiers Crus classes‘ are paid between 90% and 99% of that price, and the others are paid between 80% and 89% of that price.

Champagne is usually composed of three grapes, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, and Chardonnay, but you can find some Champagnes that are 100% Chardonnay.

Production is quite strictly controlled with a minimum of 8,000 vines per hectare (a hectare is 10,000m2), producing between 10,000 and 15,000 kg per hectare (there is a cap at 15,500 kg/ha for AOC production). Yields will vary depending upon the production techniques, type of grape, weather conditions, etc. so one can only write about averages. One can expect around 85 berries per cluster, and 8 bunches of grapes per vine (figures can vary from 75 to 100 grapes per bunch). Juice extraction is usually limited to about 6,600 litres per hectare (‘must‘ extraction is limited to 102 litres per 160 kg of pressed grapes). The exact pressing equipment and process are strictly controlled by a special ‘cahier des charges‘. So 680 grapes can be expected to produce up to about 0.8 litres, and therefore a bottle of Champagne might contain the juice from about 600 grapes. Depending upon the proportions of the three varieties of grapes, a bottle of Champagne will contain the grapes from between 6-7 bunches of grapes (or about 1.2 kg of grapes). So if a bottle yields 5 glasses, then there is the equivalent of about 120 grapes in each glass. These figures are used just to give us an idea of what a bottle of Champagne contains. The website Grandes Marques & Maisons de Champagne is a useful source of information.

In addition to the big Champagne houses, there are many, many smaller independent grower-producers or ‘vigneron‘. Returning to our view of Champillon we could actually see from the hotel terrace at least four different Champagne producers, namely Champagne Michel Bahuchet Pere et Fils, Champagne Pascal Autréau, Champagne Roualet Pere et Fils, and Champagne Gisèle Devavry. However it is not said that the vines growing in front of the hotel actually belong to one or more of these producers. As an example, the Devavry family collects grapes from Champillon, Hautvillers, Romery, Aÿ, Sermiers, and around Sezanne.

In the minds of many people Champagne is synonymous with Reims, and people tend to ignore the fact that Épernay is the ‘capital of Champagne’. In the centre of the town there is the famous Avenue de Champagne where you can find many leading Champagne producers (19 of the larger houses are in this town as compared to the 22 in Reims).

Now returning for a moment to that first landscape, sitting on the hotel terrace I asked myself what that flat range on the horizon is? And this question opened up the intriguing topic of the French passion with ‘terroir‘, i.e. a place with its own mix of geology, climate and methods of viticulture.

People write books about the ‘terroir‘, so it’s well beyond the scope of a simple tourist-inspired report, and yet I remained intrigued by the landscape before me. For the moment let’s just think of ‘terroir‘ as a combination of soil type, slope, drainage, etc. and ignore those who think of it as just another marketing ploy (but if you are really interested in the topic check out “Geology and Wine: A Review“).

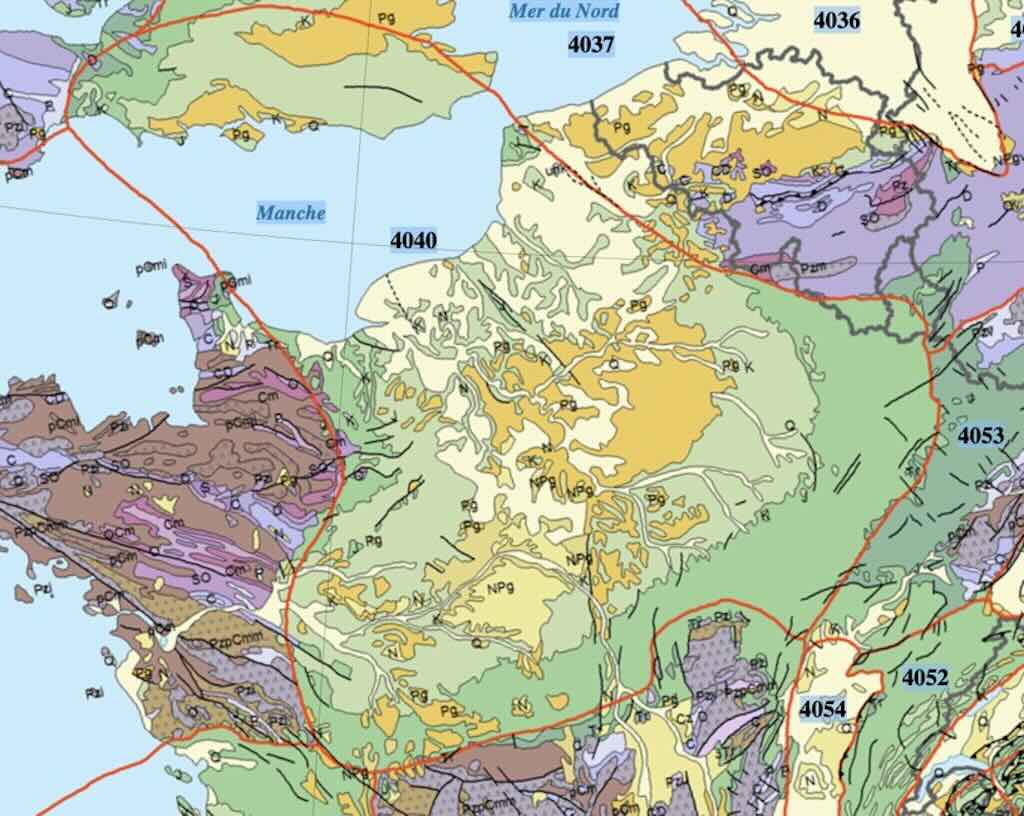

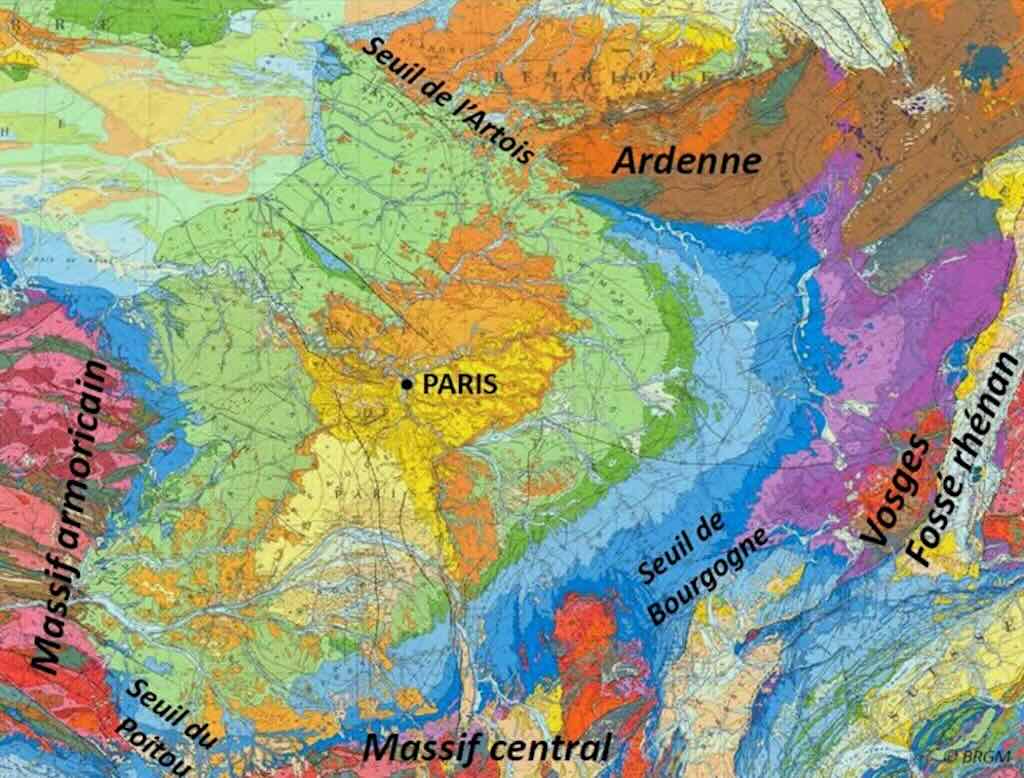

We start with the ‘geological province‘ in which the Champagne region is found, its code 4040 and defines an extended zone of crust called the Anglo-Paris Basin, in which the better known Paris Basin can be found.

I will not go into how the Basin emerged, but clearly we can see that it is ‘jammed’ between a series of massifs, i.e. the Massif Armorican, the Vosges, the Ardenne, and the Massif Central.

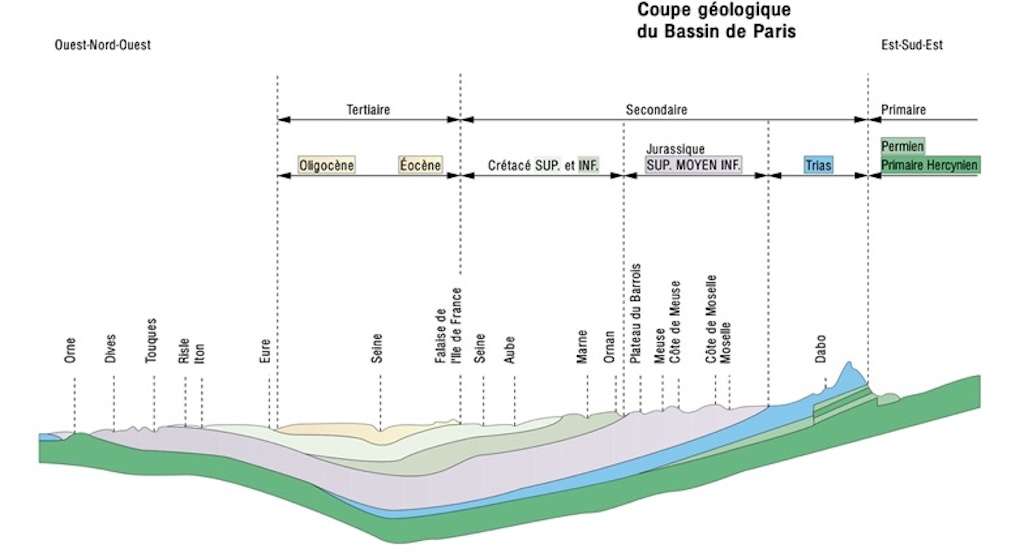

During a period called the Cenozoic (66 million years ago) the early land masses were stretched and opened up to the seas. Large quantities of clastic materials were deposited in basins in repeated transgressions–regressions of the sea (so Late Triassic siliciclastics, Lias-style shales, Doggerland carbonates, and Late Jurassic clays, all predominantly sedimentary rocks).

With the return of the sea during the Cretaceous period, chalk was deposited (marine deposits that became another type of sedimentary carbonate rock). In the late Cretaceous period there was a period of widespread uplifting (compression and deformation) which isolated the Paris Basin. The different structural faults became drainage lines that eroded the landscape (and finally became the rivers we know today).

For those readers interested in the way to see the geology around us, and in particular in the Paris Basin, check out the blog ‘Written In Stone‘.

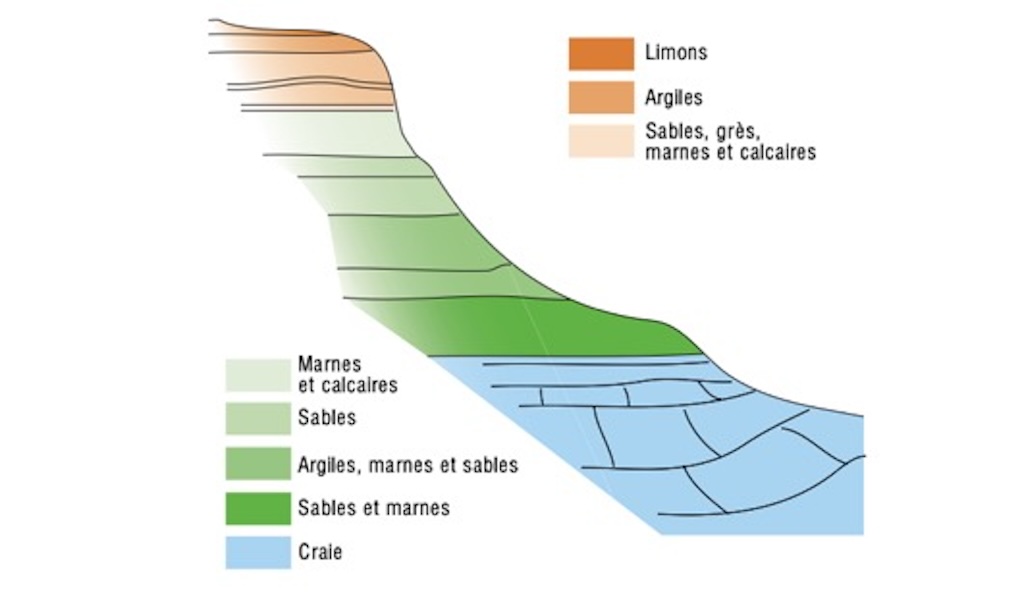

The result of those millions of years is seen in the above cross-section through the Paris Basin. And we can see that the Champagne region sits on a sub-soil from the so-called Lower (Early) and Upper (Late) Cretaceous periods. As we move from Paris (Seine) towards the East and the Jura we are going back in time, from the most recent towards the oldest deposits.

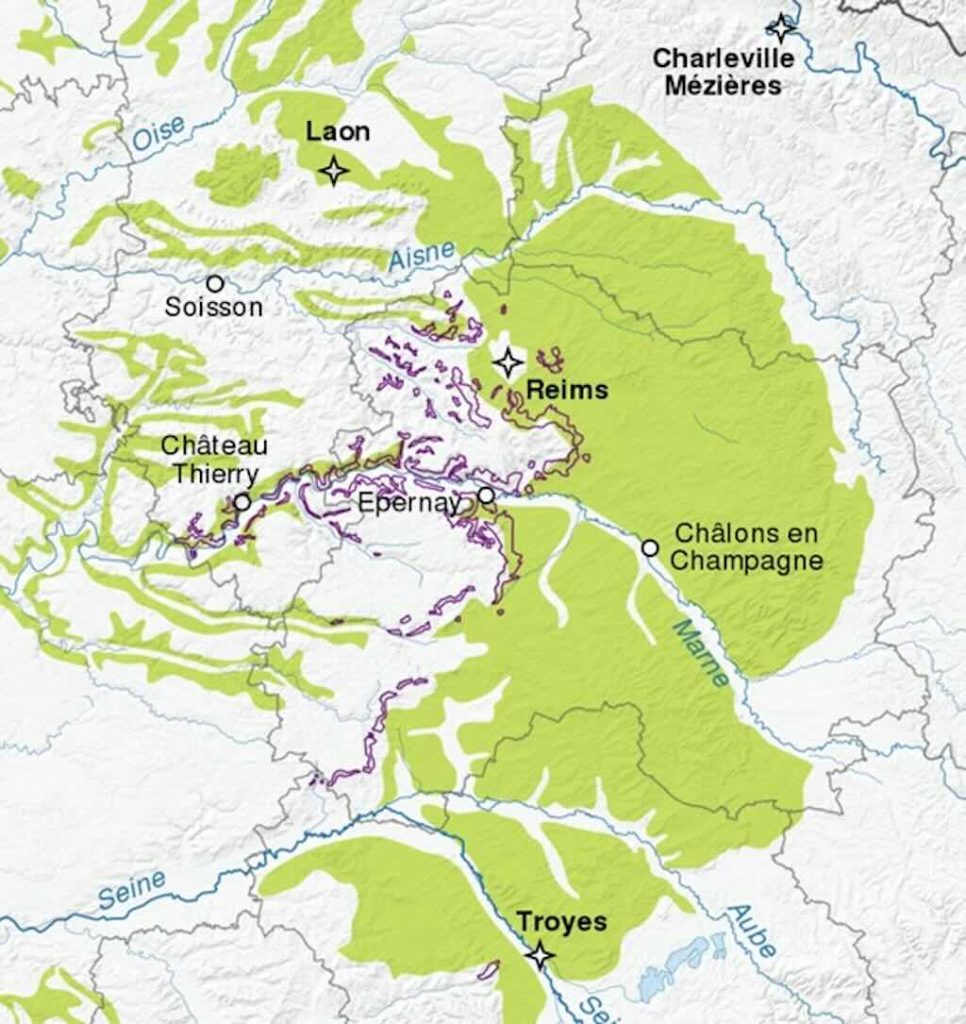

In fact the geology of the champagne region is divided into Champagne crayeuse (‘chalky Champagne‘) and Champagne humide (‘wet Champagne’). We can see below the so-called Champagne crayeuse in green and the Champagne ‘vignoble’ marked out with the colour bordeaux-red.

The region Champagne crayeuse is also called Champagne pouilleuse or Champagne sèche, i.e. ‘pouilleuse‘ probably is best translated as lousy and not fertile, and ‘sèche‘ or dry simply in opposition to wet Champagne and suggesting a porous soil. This is the most common type of soil in the Champagne region and is home to the vines needed for Champagne.

As the Wikipedia article on the region suggests, a soil that is poor and porous is ideal for Champagne vines. However the reality is that it is a soil that takes well to fertiliser and does retain some moisture, and has been used often for growing cereals, sugar beet, and potatoes. In fact its porosity means that it becomes a kind of hidden reservoir of water (300 to 400 litres/m3) which allows the vines to draw water during the dry months.

The land is full of slopes, and occasionally you can see chalk outcrops. Initially in the small dips and valleys villages emerged cultivating only the land near streams, etc. The rest of the land was left for sheep farming. In the latter part of the 19th century black pine was planted producing huge forests and the villages appeared to occur in small isolated clearings. Now with machine cultivation and fertilisers, and the loss in 1953-54 of all the rabbits in the forests due to myxomatosis, the forests have been cut down, leaving place for perfectly cultivated landscapes.

The region Champagne humide is in part classed as natural parkland due to the fact that its relatively flat, and the lakes have become popular tourist attractions.

So coming back to our original question, what we see in the distance are small hills and dales. Below we have a detailed view of the ‘surface’ geology of the region. If you look carefully you can see that each defined area has a small numerical code indicating a type of rock under the surface. We can see Reims sitting on a wide area of chalk (Late Cretaceous).

If we draw a line more or less straight from Reims to Épernay we will find the road D951 that took us from Reims to Champillon. We can see that as we drive out of the centre of Reims we cross a dry alluvial river bed. As we drive south we cross large areas of chalk soil interspersed with mixed outcrops of loess, i.e. a kind of wind-blown sediment coming from the erosion of Paris Basin.

We are heading towards those darker brown areas. We are going to cross the eastern part of the so-called ‘Montagne de Reims‘. The idea of a ‘mountain’ is subjective, and is used to underline a brusk change in altitude, rather than a mountain in the classical sense. It is really more like a wooded plateau, and in fact we will drive through the ‘Parc Natural Régonal de la Montagne de Reims‘.

It is on the southern-facing slopes of this ‘mountain’ that we find the vineyards of Champagne. This ‘mountain’ is really just a thick compact blanket of loess, tens of metres thick and covering a vast area. As we come out of the park forest we find Champillon sitting on the southern slope, ideally exposed to the warmth of the sun in the summer months.

Now can begin to understand better what we are seeing. We can see another wider dry alluvial river bed with the town of Épernay sitting on the far side. And just behind the town we can see again a tree-covered plateau of loess. Because of the nature of the grains that make up loess, vast banks were created that remained intact for considerable periods of time. These loess ridges, that we can see sitting behind Épernay were probably aligned by the prevailing winds during the last glacial period, and in Europe these ridges are often called ‘greda ridges‘. Below we have a cross-section through a typical ridge in the region.

Whilst the loess can be seen as a superficial deposit they nevertheless have resisted time, and today give the Marne Valley a very contrasted landscape with the smooth, wavy hills and dales of the Champagne region, the region of the lakes, the forests, etc.

All created by the local geology.