As we get older we all become more interested in the macabre subject of death. Even if it is best viewed as how to live a long and happy life, hopefully free from problems such as heart attacks, cancer, etc.

My beloved wife Monique passed away on at 17:00 on the 23 December 2023. She took her health very seriously, so naturally I also took her health very seriously. But now I have started to take more seriously my own health.

One super important aspect is to understand my own risk profile, and what I should do to improve it. And that starts with a detailed assessment of my present state of health.

Topics:-

- Life Expectancy

- Cause of Death

- How I/You Will Die

-

Avoiding Dementia

But let's first remind ourselves...

That across the European Union (EU), a commonly cited benchmark for a comfortably manageable patient list per general practitioner (GP) is around 1,800 patients per GP. Given that the annual mortality rate on average across EU populations is about 1%, that means ~18 deaths per GP’s patient list per year. The ~18 deaths per year happen mainly among elderly or already seriously ill patients. In older populations (e.g. rural areas, retirement hubs), the GP may see 25–40 deaths per year. But the GP may not be involved in end-of-life care for all patients who die (e.g. hospital deaths, nursing homes).

The average general practitioner (GP) in the EU sees approximately 4,000 to 7,000 patient contacts per year, depending on country, system structure, and workload. This includes face-to-face consultations, home visits, telephone/video calls, and administrative reviews. The typical GP in the EU works around 35 to 50 hours per week, but clinical contact hours (time actually spent seeing patients) are usually 25 to 35 hours per week, depending on country, practice structure, and administrative workload. So the time spent with a patient (on average) will be 10–20 minutes. A contact is any clinical encounter where a diagnosis, treatment, follow-up, or advice is given. And this includes remote consultations, repeat prescriptions, lab reviews, and mental health check-ins.

Between 35 and 70 patients on a GP’s list of 1,800 are likely to be seriously ill at any given moment. This means having a life-threatening, life-limiting, or disabling chronic condition, which require ongoing specialist care, hospitalisation, or palliative attention, and where there is a high risk of deterioration or death within 6–12 months. Around ~75% will require close specialist/shared care that can not be provided by primarily care alone.

A further 15–25% of patients may have moderate chronic conditions (e.g. diabetes, stable heart disease, depression), so not “serious” but still requiring regular attention.

With a patient list of ~1,800, each patient could be seen 2–4 times per year on average. However 50–60% of a GP’s workload is spent on the “moderately ill”. Typical conditions for the “moderately ill” are hypertension, type-2 diabetes (non-insulin), stable angina, chronic mild/moderate asthma, early COPD, mild/moderate depression or anxiety, early-stage arthritis, and thyroid disease.

It is these patients with common, manageable but ongoing conditions that require regular GP review (e.g. every 3–6 months), monitoring tests, medication adjustments, and occasional referrals. These patients form the core business of modern general practice.

The remaining patients will visit the GP for both minor/acute but short-lived issues such as colds, flu, sore throat, minor injuries, skin rashes or infections, urinary tract infections, back pain, and gastroenteritis. In addition there are those on low-complexity medication (e.g. mild hypertension or thyroid replacement), who may only need an annual review and repeat prescriptions. Finally there are healthy individuals, who require preventive care (e.g. vaccinations, health checks), travel advice, and screening (e.g. cervical smear, mammography referral).

On a typical GP list in the EU, about 10% to 20% of patients do not visit their GP at all in a given year. It possible that 30–50% of those who did not visit a GP had at least one medically justifiable reason to do so but didn’t. It is these people who develop preventable complications, receive late-stage diagnoses (e.g. cancer, diabetes), or end up in emergency care.

According to Eurostat and OECD data about 33–40% of all deaths in the EU are considered premature or preventable. But that varies from 25% (e.g. Sweden, Netherlands) to 50%+ (e.g. Romania, Bulgaria). Our average European GP will see ~6 to 7 people per year who will “die before their time”.

Probably the single most important thing a person can do is to recognise and act on symptoms (e.g. for unexplained weight loss, chest pain, persistent cough, depression). Delayed help-seeking is a leading cause of missed diagnoses.

Next is just managing known chronic conditions. This means control of diabetes, hypertension, asthma, etc. which prevents stroke, heart attack, kidney failure, etc. Everyday adherence matters more than occasional screening.

Thirdly, screening for cancer, blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes catches problems early, i.e, when they’re treatable. Especially vital for asymptomatic diseases (e.g. bowel cancer, hypertension).

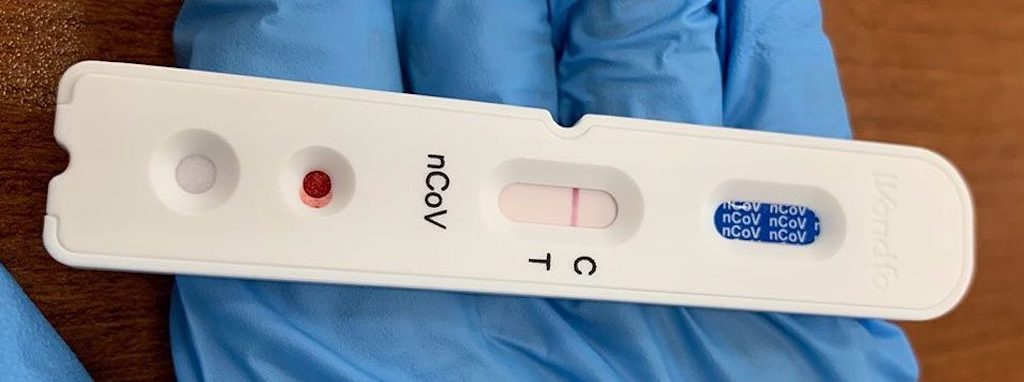

Then comes vaccination and prevention (e.g. flu, pneumococcal, COVID, shingles, HPV).

And finally, health literacy and self-care should not be forgotten. Understanding when to seek help, how to interpret symptoms, and how and why to follow medical advice helps everyone, everyday.

In 2023, the five major non-communicable disease (cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, mental health) cost the EU economy an estimated €530 billion. That ~3.13% of EU GDP. Of that, ~60% were direct healthcare costs, the rest indirect (productivity loss, informal care). Up to 86% of deaths in Europe are attributed to chronic diseases largely caused by modifiable risk factors, namely smoking, poor diet, inactivity, and harmful alcohol use. It’s true that the majority of these deaths occur after age 70, but many are preventable or could be delayed. Up to 40–50% of these deaths (especially in people under 75) are classified as “premature” and linked to modifiable risk factors.

It’s not rocket science

If people want to dramatically improve their health they simply have to increase their daily physical activity.

Physical inactivity is a leading underlying cause of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, some cancers, and mental health issues. It’s a common problem across all ages and income levels, and is often the root cause or enabler of other risk factors (like obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance).

One in three adults and four in five adolescents in the EU do not meet minimum WHO activity recommendations (150 min/week of moderate activity).

It’s simple, sitting is the “the new smoking”

Brisk walking (30–45 minutes/day, most days) is the single best exercise for the general population across all age groups.

“Brisk walking” means at least 5–6 km/h pace (noticeable breathing, but still can talk). Ideally 30+ minutes per day, but even 2×15 mins helps. Including hills, stairs, uneven ground increases impact.

But even modest daily walking, without equipment, special clothing, or tracking, provides clear, measurable benefits.

A daily walk is the foundation of preventive medicine.

The ‘Blue Zone’ is a place where people are claimed to have exceptionally long lives. This means living beyond the age of 100. The claim is that this is due to a lifestyle combining physical activity, low stress, rich social interactions, a local whole foods diet, and low disease incidence.

This does not look particularly surprising. Most people, if asked, would mention several of the above as reasons contributing to a longer lifespan.

The five original ‘Blue Zones’ were Okinawa (Japan), Barbagia region (Sardinia, Italy), Nicoya Peninsula (Costa Rica), Ikaria (Greece), and Loma Linda (California, USA).

The reasons are as follows:-

- Okinawa – strong sense of purpose (ikigai), plant-based diet with soy and sweet potatoes, close-knit social circles (moai), and respect for elders.

- Barbagia region – pastoral lifestyle with lots of walking, moderate wine consumption (especially Cannonau red wine), lean but nutrient-dense diet, and deep family cohesion.

- Nicoya Peninsula – life purpose (plan de vida), diet built around beans, corn, and squash, strong family ties, hard water rich in calcium/magnesium, and daily physical activity.

- Ikaria – Mediterranean diet rich in vegetables, legumes, and olive oil, herbal teas, daily naps, regular fasting (linked to Greek Orthodoxy), and social/community bonds.

- Loma Linda – faith-based community, vegetarian/plant-heavy diet, regular moderate exercise, weekly day of rest (Sabbath), and no smoking or alcohol.

However, the concept has been challenged by the absence of scientific evidence.

A recent BBC article mentioned Singapore as the 6th ‘Blue Zone’, or more specifically a ‘Blue Zone 2.0′. This distinguishes it from the original five, which emerged organically from traditional lifestyles. In contrast, Singapore represents a deliberately engineered Blue Zone, built through modern policy design rather than heritage and culture.

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the estimate of the average remaining years of life at a given age.

The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth. For the US population this is around 79, for the UK its around 81, and for my country of residence its around 82 (the world average is around 73).

But what interests me, and you, is life expectancy now. For me, this means a white male, over 70. This is best expressed as “Years Left to Live”, and for me its 32% (0 to 9 years), 48% (10 to 19 years), and 19% (20 to 29 years). That just leaves a 1% chance of getting past 100.

The key statement is that I have a 68% chance of getting past 80.

What’s also interesting is that the longer you live, your life expectancy changes and improves. If I make 80, my life expectancy might be 59% (0 to 9 years) and still 38% (10 to 19 years), and I would have a 3% chance of getting past 100.

So as an 80 year old I would have around a 40% chance of making 90, whereas as when I was 70 years old, the probably of making 90 was only 19%.

Cause of death is all about how other people have died. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classifies death into 113 causes, which are grouped into 20 categories of disease and external causes.

113 causes is a bit daunting, if one thing doesn’t get you, another will.

I’m of course interested in what my risks are, as a white male, over 70. But we have to start by looking at how the overall (US) population dies.

It looks like cancer is the main cause of death up to the age of about 60, and then circulatory problems start to take over, and respiratory problems also start to become significant. This is based on cause of death marked on US death certificates between 2005-2014.

Circulatory system diseases affect the heart and blood vessels and make it harder for blood to flow throughout the body, so it covers both cardiovascular diseases (including heart attack and heart failure) and vascular diseases (including blood clots). Some conditions have symptoms, but others are silent. Common symptoms include chest pain, edema (fluid retention), heart palpitations and shortness of breath.

Respiratory diseases include bacterial pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, tuberculosis, acute asthma, lung cancer, and severe acute respiratory syndromes.

This is a truly macabre heading, but it just means looking at the risks facing someone who is (still) a living white male, over 70.

What we see is that my main risk/cause of death is already circulatory, and will increasingly be so for the rest of my life.

As an example, should I survive to be 80 years old, circulatory problems are at 37%, compared to cancer at 29%. Given that cancer is often perceived as the main cause of death, the key message is to not underestimate the risks of circulatory problems.

Avoiding Dementia

2025.02.15 How to cut your dementia risk

It suggested that visual sensitivity can predict dementia as many as 12 years before it’s formally diagnosed. And it may be that people who watch more TV and read more have better memory and significantly lower dementia risk (possibly because of eye movement).

Being more educated and having a higher-quality education tends to be associated with better health outcomes, and the same is true for dementia.

According to the Alzheimer’s Society, persistent loneliness (social isolation) can increase a person’s dementia risk by around 60%.

Of the so-called ‘big five’ traits (conscientiousness, extraversion, openness to experience, neuroticism and agreeableness), which ones affect the subjective measures of wellbeing (positive and negative, and life satisfaction). High conscientiousness and low levels of neuroticism had “really clear links to a lower risk of dementia diagnosis”.

Scientists have found a link between how much polluted air someone is exposed to and their risk of developing dementia in later life.

It’s been long established that a dementia diagnosis often goes hand in hand with disturbances in sleeping patterns.

A normal night’s sleep is seven hours and consistently getting less than this was associated with a 30% increase in dementia risk.

What’s good for the heart is good for the brain. In other words, preventing cardiovascular disease and diabetes, maintaining a healthy weight, keeping blood pressure low and avoiding smoking will all reduce the risk of dementia.

Next steps

The next step is to assess my existing risk profile, and then to understand how to manage/reduce the most important risks.