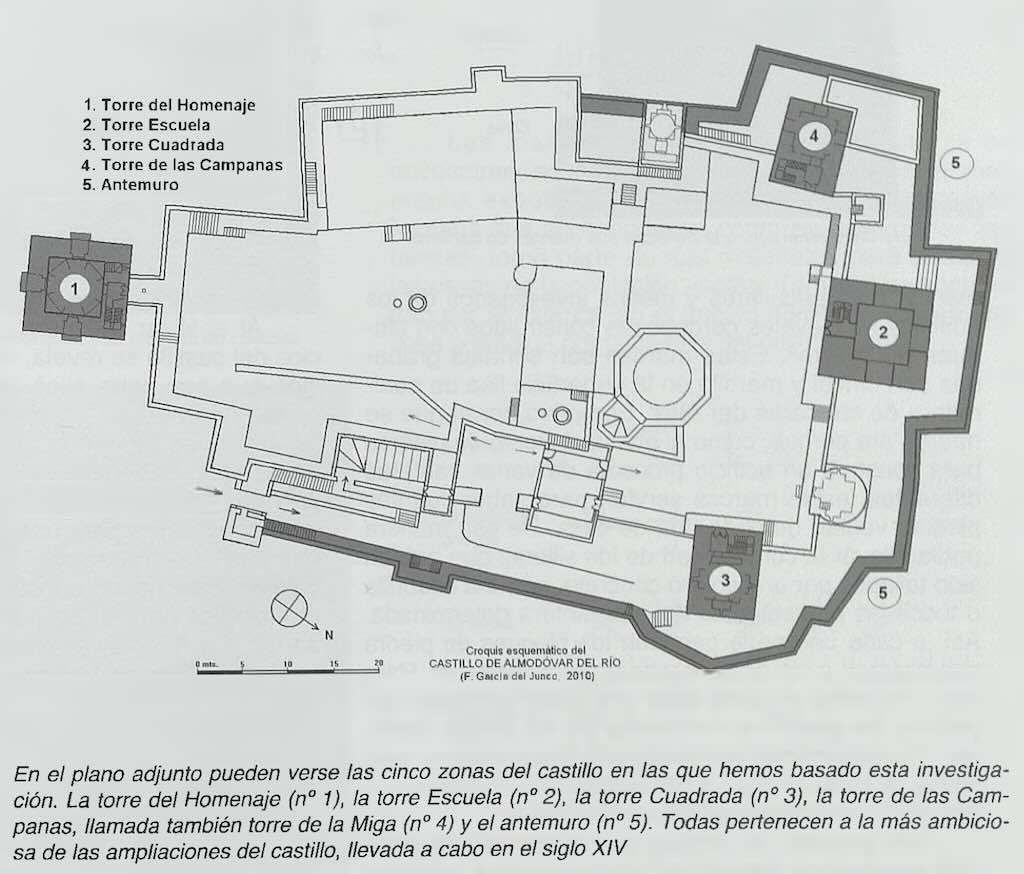

Castillo de Almodóvar del Río is an impressive castle located about 25 km outside Córdoba. We will visit the castle, and also learn about some stonemasons marks.

The castle’s origins date back to Roman times. The actual construction, however, was built by the Arabs in 760. Under the rule of Fernando III it became a Cristian strong-holding in 1240, and under Pedro I and Enrique II it even served as a royal residence. Photos in one of the rooms of the castle show that it had been totally abandoned when in 1903 the 12th Count of Torralva began his 33 year restoration program.

According to the Chronicles of Fernão Lopes the Almodóvar castle was where Pedro I kept his “gold, silver coins, precious stones and pearls”.

Today the castle looks to be run as a commercial tourist attraction, but it’s worth the visit anyway. We visited the castle on the 14 May 2010, but I’ve seen that it now has its own website. These photos were taken during our visit, but the website hosts an impressive set of more recent photos as well. Also Wikipedia mentions that the castle also appeared in Game of Thrones.

Below we see the entrance path with the main eastern wall, and the the Torre del Homenaje in the background.

Below I think we can see the Torre Escuela more or less in the middle, with Torre de las Campanas to the left, and the Torre Cuadrada to the right

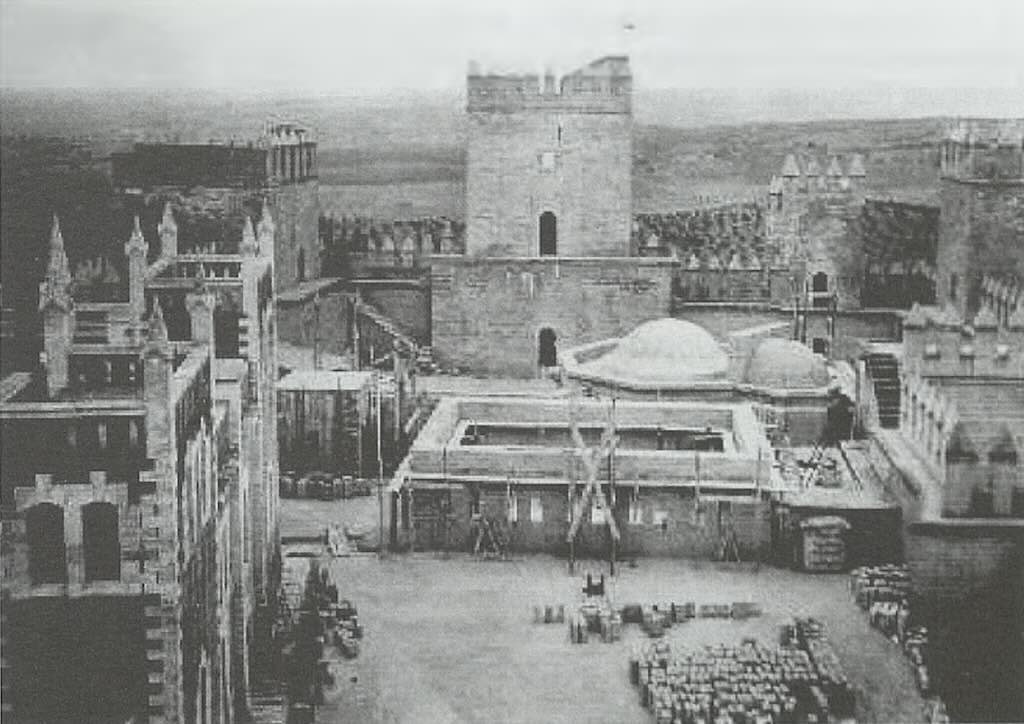

Below we can see more or less the same view dating back to 1923.

Above we have the impressive balcony on the Torre del Homenaje, and below we have my princess surveying her domain.

Typically the Torre del Homenaje was the lord’s residence (residencia del señor). Generally it would have been divided into three or four floors, each with a room. For defensive reasons, the entrance was on the first floor, which was, in turn, the main floor (the throne room). The upper floor(s) were occupied by the lord’s private chamber. The ground or bottom floor of this tower was a dungeon around 12 metres by 12 metres, with the walls between 2.5 metres and 3.5 metres thick, and access through a small hole through the ceiling 7.5 metres above the floor. The dungeon had only two small holes for ventilation, set 4 metres up the walls. There was a small alcove with a small hole that served as a latrine. The base of the dungeon was cut into the solid rock. I suspect that you went in feet first, and came out in bits.

The 33-metre tower was built more than 600 years ago. On 23 July 1936, a 7.5 cm calibre shell was fired at the north-east face of the tower, but it only left a slight mark, which can be seen today.

Note on the restoration work

The actual restoration work took place in the first third of the 20th century, but it was based upon extensive historical and archaeological research. It looks as if many 19th century castle restorations aimed more at satisfying the owners idea of a castle, rather than restoring what the castle once looking like.

In some cases extravagant Gothic spires, meaningless machicolations and very small halls were “restored”. For example, the Alhambra in Granada has gone through several phases of restoration and the results were very varied. It started as a recreation of a Moorish atmosphere, as was expected during 19th-century Romanticism. Only a later restoration aimed to recover the authenticity of a Nasrid palace fortress, as it really had been.

With the work on this castle it was important that the architect in charge of the works was Adolfo Fernández Casanova (1844-1915), who had extensive professional experience. He restored La Giralda, the bell tower of Seville Cathedral. There was an old but useful description of the castle’s buildings and state of conservation, but it only dated from 1837. Fortunately the immense stone mass of the castle did not go unnoticed, which meant that 19th century traveller who came to Cordoba often described the castle in a more or less concise manner.

Below we can see the castle in 1904, and again in 1916.

One additional point that I did not see mentioned in our visit in 2010 is that this castle has one of the most extensive networks of underground passageways and rooms in European castles. This included two 8th century cisterns (los aljibes) built at different levels (capacity 290,000 litres), and a later cistern built when the walls were extended in 10th century.

Finding unexpected details

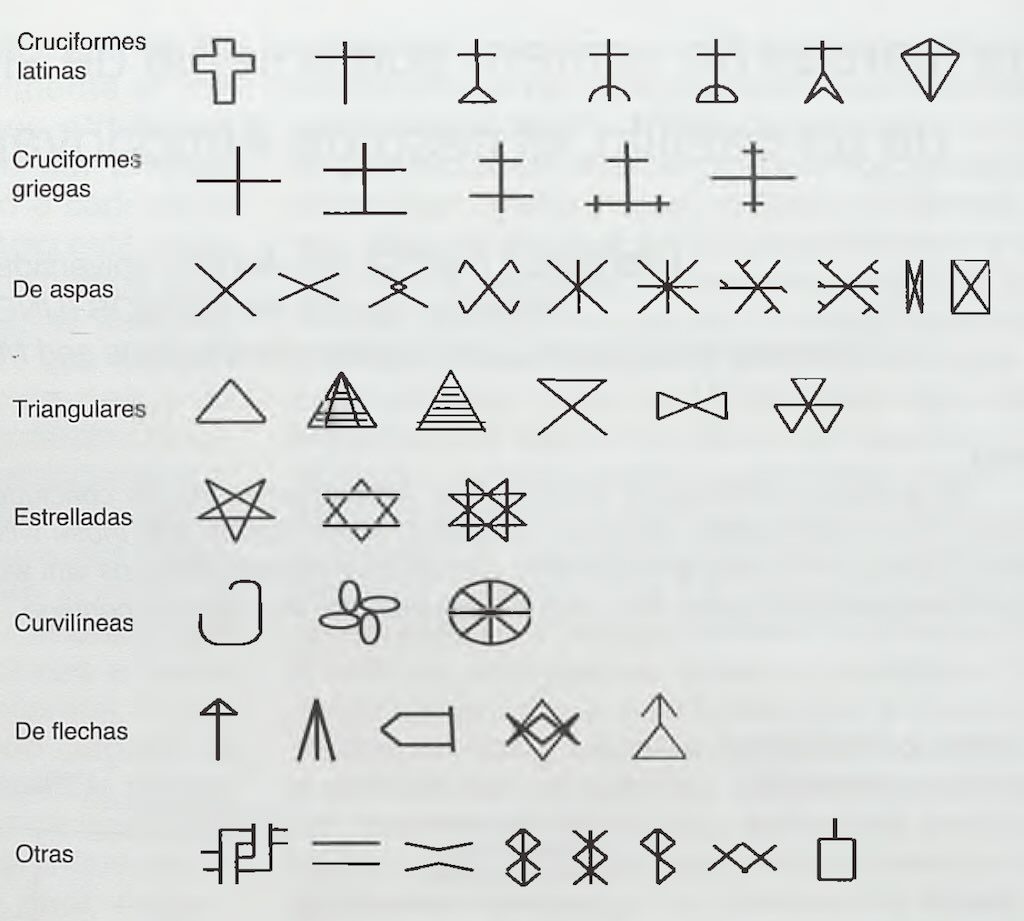

During a renovation, almost independent of its complexity (or simplicity) it was possible to discover hidden details. Craftsmen involved in the building of such castles would leave stonework marks on each and every stone block. These marks are signs engraved with a chisel and hammer on the smooth surface of any of the faces of the ashlar (cut and dressed stone). The reason why they were made was because, as the supply of stones came from several different quarries, these marks served to know how many stones came from each one of them. In this way they could keep an account of the ashlars that had been carved by a specific stonemason, by his team, and all the stones from a specific quarry. Thus, each quarry was paid for the stone blocks that arrived at the construction site and had their marks. The accounting was kept in a simple but effective way, each quarryman or worker was paid for the ashlars that had arrived with his mark.

In general, the stonemason’s marks on medieval buildings tend to be simple compositions that required little work and, most of them, were easy to make. At the same time, the number of strokes and the resulting composition had to form a figure that was easily distinguished from the marks of other stonemasons working on the same project.

The marks shown above, found both inside and outside the buildings, demonstrated it was built over an extended time period. There were many different stonemasons who intervened in extending the castle during the 14th century. And the marks showed that the stonemasons who worked carving ashlars for this castle were the same ones who worked on other medieval buildings in Córdoba. In fact the number of different marks found was 74, of which 34 (46%) were repeated on several different buildings in the region.

Reference

Francisco García del Junco, Fundamentos Teóricos de la Restauración del Castillo de Almodóvar del Río (Córdoba), 2012 (see his publications)