My collection on Cádiz includes Cádiz I, Cádiz – II, Cádiz – Today, Cádiz – Maps, Models and the Camera Obscura, Cádiz – El Centro, Cádiz – El Pópolo, Cádiz – El Mentidero, Cádiz – San Carlos, Cádiz – Nochebuena and Nochevieja, and Cádiz – Trafalgar (this posting).

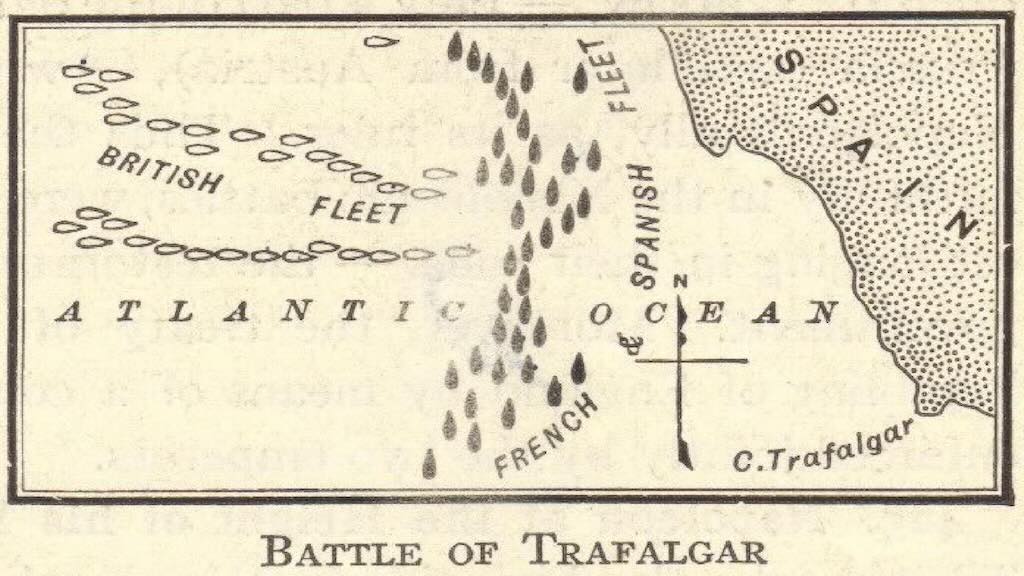

Wikipedia tells us that the Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of French and Spanish ships. It took place on the 21 Oct. 1805 in the waters in front of Cádiz, and was part of the War of the Third Coalition (1803-1806) of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

“Rivers of ink” have cascaded down millions of pages about this battle. It is pointless trying to provide another summary. However, it did take place in the waters near Cádiz, and it did involve the city, so we need to include it in our “visit”.

Despite the profusion of information on Trafalgar it is quite difficult to get a good, detailed plan of where the battle actually took place. However there is a Faro de Trafalgar on a promontory of land just west of Los Caños de Meca. Oddly the Spanish Wikipedia article on the Batalla de Trafalgar is more complete in this respect.

The role of Cádiz in this battle was as a base for the combined fleets of the Spanish and French. Essentially the British fleet established a semi-blockade on the Franco-Spanish fleet. In addition many of the French ships had been kept in the harbour for years, and the crews were quite inexperienced, especially the cannon crews.

Napoleon gave orders for the Franco-Spanish fleet to leave Cádiz and take the troops to Naples. And to fight the British if they met. Some of the ships captains thought it best to stay in Cádiz, however they finally emerged from the bay. Later they would decide to return to Cádiz, but, due to light weather, they had some difficulty in maintaining a tight formation. Despite being outnumbered and out-gunned, the British fleet got the upper hand, and only eleven Franco-Spanish ships escaped back to Cádiz (and only five were seaworthy). They remained block in Cádiz until 1808 when Napoleon invaded Spain. The French ships were then seized by the Spanish.

We know how England saw the outcome of the battle, but what about the Spanish? How did they see the battle of Trafalgar? And what about Cádiz?

The only real value in this post is to understand better how Spain saw the outcome of the battle, and the consequences of defeat.

The commander of the Franco-Spanish fleet was incompetent

Most Spanish authors clearly define Trafalgar as the “episodio más negro de la historia naval española”. But equally many Spanish authors attribute defeat to the fact that the Franco-Spanish fleet was under the command of the French Admiral Villeneuve, whom they defined as incompetent, indecisive, and ineffective. On top of that many authors also noted that the incompetence of Villeneuve was well known to the authorities in Paris, and Madrid was also probably informed, so why was he given the supreme command?

It is also known that formal protests at the ineptitude of Villeneuve were made to their respective commands by both Spanish and French captains, and ignored. In fact Villeneuve was to be replaced by Admiral Rosily-Mesros, and they say that it was for this reason that Villeneuve took the fleet out to face Nelson. Villeneuve was captured, taken to England and released to France to stand trial. He committed suicide in Rennes, but all the indicators point to him being murdered on the orders of Napoleon.

Most experts conclude that Villeneuve was courageous, polite and studious, but he was a defeatist, and not equipped to command. He did not believe that England could be invaded, nor did he have confidence in his allies or subordinates. Nelson was bold, tenacious, imaginative, independent, and an ambitious tactician. Game, set, and match!

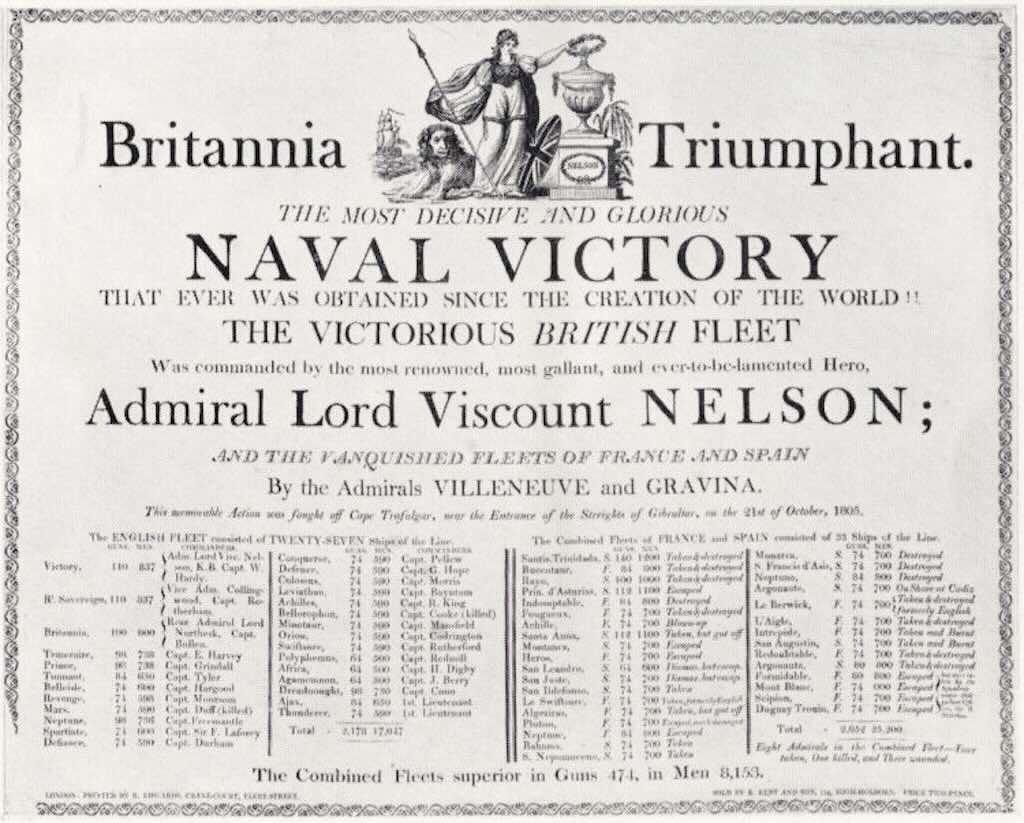

On paper the Franco-Spanish fleet had the advantage:-

- 33 ships against 27

- 3,000 cannons against 2,500

- 22,000 men against 17,000

At the end of the battle:-

- 3 Spanish and 2 French ships were captured

- 14 Franco-Spanish ships were sunk

- The English lost no ships, but 4 were badly damaged

- 4,400 Spaniard and French killed (twice as many French as Spanish)

- 2.500 Spaniard and French wounded

- 7,000 Spaniard and French taken prisoners

- 500 English killed

- 1,300 English wounded

The conclusion of Admiral José Ignacio Gonzáles-Aller was that the English were better prepared, had better commanders, used better the available weapons, and had a better battle plan. The Spanish navy was left frustrated. The sacrifice had been useless, and Spain had lost the command of the Atlantic. France could not challenge England on the high seas. So England could not be invaded. The English could now do what they wanted, and they chose colonisation and commercial power. The Spanish reinforced their shipyards and armories, and within 5 years had recovered from their material losses. But the damage was done, England ruled the waves through all the 18th century and most of the 19th century.

Spain was left with a strong anti-French sentiment.

Spanish naval doctrine

The origin of Spanish naval doctrine was galley-oriented. For example the Spanish Armada of 1588 consisting of some 130 ships manned by 30,000 men, two-thirds of which were soldiers. The idea was to fight a close-in battle at sea where the Spanish would use their superiority in boarding. The English recognised the Spanish advantage in sailing skill, numbers, and tactics, so they kept their distance using long-range artillery to wreak havoc on the Armada. The English also held the superior logistical position, being close to their own ports for reprovisioning.

The Spanish felt that religious and moral superiority would be to their advantage, just as the French felt that their elan could make up for material deficiencies. It was only later that Spain recognised that they needed sailing ships that could engage in distant water combat.

The years of wars with England necessitated a method of ensuring the security of treasure ships, and the Spanish introduced the concept of convoy escorts in the mid-16th century. Initially, escort ships were essentially armed merchantmen. Even improved designs lacked manoeuvrability, although they were stable gun platforms due to the large cargo-carrying capacity built into the hull. So Spanish naval fleet construction shifted to warships designed to provide convoy escorts rather than warships designed to engage in a decisive engagement against an enemy battle fleet.

Command of Spanish ships of the line included a divided command, with one officer in charge of the soldiers at sea and another commanded the ship’s company. This system of dual command was to last for nearly a hundred years. The command and manning policy reflected a naval doctrine that called for a warship to be both a platform for small arms shooting by troops as well as a platform for artillery fire from cannon. The result was that Spanish ships generally had crews of half marines and half seamen, and consequently they could do neither job well.

The formation of a combined Franco-Spanish fleet in 1779 during the American War of Independence resulted in the issuance of French navy doctrine for both fleets. Spanish ships were both integrated within the French fleet as well as maintained as a national force which would join the battle once the enemy was engaged. Spanish naval doctrine did evolve but it remained biased in the favour of the defence and wars of attrition.

As Spain approached the 1800s its navy was short of men and supplies, and was not well trained. On the other hand the the British benefited from the experiences of frequent combat against the French and were thus fighting at the height of their combat potential. Spain was plagued by selection of officers for command for other reasons than their aggressiveness at sea. Some of the differences between the leadership and command qualities of Royal Navy and Spanish officers resulted from the longer periods at sea and longer periods engaged in combat by the British. Additional problems stemmed from the constant undermanning of Spanish ships and the lack of camaraderie of the crews.

At the Battle of Trafalgar, the Spanish and French fleets operated as a combined fleet, although in separate national squadrons. There had been no combined fleet exercises for these two navies prior to the battle. Furthermore, the tacking of thirty-three warships from south to north had never been attempted by the combined fleet, and it was made all the more awkward by the light winds which prevented the formation of a solid defensive battle line. The Spanish were unable to override the defensive navy doctrine of the French and put into practice the new offensive Spanish doctrine. They would have preferred to man their ships and engage the British at a distance. There is no question over the bravery of the individual Spanish officers and men at Trafalgar.

The English navy was more modern

Concerning Trafalgar some Spanish authors also noted that England had a professional, modern navy in which they had made a considerable investment. Their ships were modern, they carried the latest designs in cannons, they used a double-piston bilge pump, the artillery had flint-locks, and sailors and officers were reasonably well paid (compared to others). The hulls were covered with copper preventing the adhesion of algae and molluscs, making them faster and more maneuverable. The English gunners were more efficient and accurate, thanks in large part to better training. The English had also adopted the carronade, a short smoothbore, cast iron cannon used as a powerful short-range anti-ship and anti-crew weapon. Neither the Spanish nor the French had adopted the carronade. The English ships were lighter, and that meant they were faster and more maneuverable. The French had invested in their land armies, but not in their navy. And Spain had mismanaged things, spent badly in past wars, and was in another economic crisis. Their fleet was old, spare parts were difficult to find, and wages were poor.

So Spanish authors concluded that the French and Spanish navies were living on their past victories. And Trafalgar wiped all those out. Some authors rightly point out that more than 140 Spanish warships were mobilised in and around Cuba, not on the Spanish coast. Yet others noted that the victory had already been decide when in 1713 Spain gave Gibraltar to the English.

Experts all agree that the shipbuilding capability of Spain had once been substantial, but it had then been forgotten, leaving a Spanish navy as “un gigante de pies de barro” (a giant with clay feet). At the time of the battle the average age of a Spanish ship was 24 years, 15 years for an English ship, and only 7 years for a French ship. For example, the Spanish ships were heavily armed and were quite fast, but they had poor stability which affected their effectiveness in battle. Spain had the firepower, but England had smaller, even faster, more manoeuvrable ships.

Over the years England had evolved its tactics from sinking to seizing ships (for the treasure). All the experts agreed that the warning signs were there when in 1797 the British fleet defeated a larger Spanish fleet at the Battle of Cape St Vincent. Twenty four Spanish ships with 2,050 cannons were “humillados” by 15 English ships carrying 1,438 cannons. The fire-rate from the untrained Spanish crews was 10 times slower than the English crews (some experts dispute this figure). The English captured four ships, including two with 112 cannons each, and destroyed 4 other ships. Spain lost 430 seamen, more than a 1,000 were wounded, and 3,000 were taken prisoners. England lost 73 seamen, and 500 wounded. Spain tried the Admiral and four captains for cowardice. The reality was that English ships were more seaworthy, the crews better trained, the commanders were allowed to be bolder, the accuracy of the gunners was better, the fire-rates were better than the Spanish, and the English crews were also more motivated to board and fight to seize valuable prizes.

The English navy was governed by professionals and promotion was on merit, whereas in France and Spain high positions were filled by the King or at least by political appointment.

The British Admiralty looked after everything to do with the sea, it was almost a mini-government. The Spanish navy was also run by high-quality individuals, however the French navy was run by Denis Decrès, a courtier and incompetent.

The English crews were better trained

The skills of the average French and Spanish seamen was poor. The French were imbibed with the revolutionary spirit, and the Spanish had some seamen who were competent but grossly underpaid. However, over the years the Spanish aristocrats had avoided the navy, and the training of midshipmen (future officers) was inexistent. Equally the English navy promoted greater freedom in decision making, whereas the French and Spanish were too stiff in their chain of command. The tactics employed by the two opponents was largely dependent upon what the crews could manage. The Franco-Spanish tactics were conditioned by crews full of inexperienced sailors, and in many cases they could not or would not obey orders.

British officers were probably less well educated than their Spanish and French counterparts, but they were far more knowledgable about the sea. In England war was a business, and sailors were considered military personnel.

To access the best positions you had to either have gone through Naval School, or have had 12 years duty experience, pass exams to be a lieutenant, and have crewed on a 3-decker. Influence peddling was frowned upon. French naval school had gone through a bad period after Louis XVI, but had recovered. However the navy had been decimated, and many politicians had entered the navy. In the vacuum they had quickly achieved high ranks without having the necessary skills and experience. At the time of Trafalgar the French officers were (again) disciplined and effective, but the captains and admirals were of poor quality. Officers who did not “fall-in-line” were court-martialled, so tactical prudence was the rule. Few of the officers had experience of long voyages, practical tactics, and major combats.

The Spanish training was based on the French model, in-depth theoretical knowledge, but little or no practical experience. Again officers could be court-martialed for different reasons, including lack of courage. At the time of Trafalgar morale in the Spanish navy was very low. Spanish commanders were veterans with combat experience, but the officers were all newly promoted and had little practical experience.

In the English fleet the captain was master onboard, and the boatswain kept the books. On French and Spanish ships you had an independent representative of the Inspector General who kept the books, and could “dilute” the authority of the captain. In the English fleet the captain could be chaplain for Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians, whereas on Spanish and French boats you had an independent priest answerable to a “higher-authority” (and they could cause problems with some crews). Also surgeons on French and Spanish boats had to be qualified doctors, whereas English surgeons did not need formal qualifications, just practical experience.

There were major differences between volunteers and conscripts. The English used mostly volunteers, but some could be underage. Adventure, a career, there were many reasons to join the navy. Moral was good, and the crews had more respect for the commanders.

Training also included using hand arms and boarding. The English navy was more concerned about the wellbeing of the crew, but order and discipline was harsher. Conditions on board were hard, but the conscripts in the Spanish and French navies were not even allow to go ashore. France also recruited in the colonies, but artillery was an elite corp, and most seamen got little or no practice as gunners. Spain recruited criminals, “vagos” and thugs, as well as volunteers. Crews were not specialised, they were poorly trained, and had little practical experience. Also in 1800 yellow fever had arrived from the West Indies and had killed nearly 8,000 people in the Cádiz region alone. The reality was that the first cause of mortality in all the different navies was first accidents, then illness.

Napoleon made mistakes

Traditionally France and Spain saw a navy battle as a support to a land battle. A navy was used to land troops, and to immobilise costal forces. On top of all that Napoleon clearly thought that the army was the most important force in war, not the navy. So the French navy lacked material resources and training. In fact Napoleon had often replaced second-rate ex-aristocrat captains with soldiers who also had no idea about seamanship.

Whereas Spanish authors saw their navy as pitiful, poor, lacking in motivation, and operationally ineffective. Spain was a vassal of Napoleon and the fleet was little more than just another currency to be spent as needed. In both the French and Spanish navies the seamen were often convicts and peasants, with no training and poor motivated. Some of the seamen had never sailed before, and the shortage of qualified seamen was endemic.

In addition at the outbreak of the conflict the Spanish navy was simply not ready. A large part of their fleet was in Cuba and the rest was still in the shipyards, but in order to keep costs down they were not armed, and the crews were not ready and trained. At the time of Trafalgar a 3-deck ship needed 630 people, with 190 gunners, 240 sailors, and 200 apprentices. A smaller 80-gun ship needed a crew of 390, and a frigate needed 180 men. At the outbreak of the war with England the Spanish navy was recruiting fishermen as crew. However, even then the navies of England and Spain (and allies) were more or less on equal terms. It was the English who got the upper hand by being better equipped to maintain blockades on Toulon, Cartagena, Cádiz, Rochefort, Brest, and El Ferrol.

Spanish experts also commented negatively on Napoleon himself. He did not know sea-warfare. His plans were “too perfect” and nothing was allowed to go wrong, but he did not consider winds, tides, the capabilities and limitations of the ships, and the training of the crews. The reality is that even if Villeneuve had joined the fleet in Brest, invading England would still not have been feasible because Frances Grande Armée was about to be attacked on land by a new coalition (England, Austria, Russia, Naples and Sweden).

Several of the Spanish authors suggest that Spain was convinced that the Franco-Spanish alliance could not succeed in invading England, and that the Spanish fleet could not win against England. But careful management of the Spanish fleet could ensure that they would not lose either.

And Cádiz in all that?

In the years leading up to Trafalgar things had not gone well for Spain, nor Cádiz. Past wars against England had not gone well. Carlos IV (1748-1819) had issued paper money causing inflation. Spain had borrowed, yet was not prepared to collect taxes from the nobility or the clergy. The English had almost killed the Spanish trading routes with the Americas. In 1792 customs taxes on that trade had brought 182 million reales into the states coffers (approx. £5 million at the time or £200 million today, but in silver terms that represent about 4,500 tons which on todays market is worth about £1.7 billion). By 1798 this had fallen to 47 million reales, a drop of 75%. In fact 30 commercial banks in Cádiz had been driven in to bankruptcy.

At the time of Trafalgar the English population was about 16 million, France 25 million, and Spain 10 million. However yellow fever had affected Andalusia, killing 120,000 to 150,000 people, often seafaring folk. It was almost impossible to find good crewmen.

Cádiz suffered under the English blockade. Admiral Collingwood commanded a 3-deck ship, 6 single-deck ships, and two frigates. They blocked the port, intercepted anyone approaching the port, and still watched out for attack. They were supplied from Gibraltar, Portugal and Morocco, and Cádiz never really recovered from that blockade.

It is interesting to learn that the actual conflict at Trafalgar took place almost at midnight, and the gunfire and explosions could be seen and heard on the roofs of the towers in Cádiz. After the battle the remaining French and Spanish ships tried to return to Cádiz, but there was a storm and the damaged ships were difficult to control. Cádiz had proven itself in 1797 as a good defensive port for the remains of the fleet. The next day people could see the ships trying to enter the port and being pushed on to the rocks. They say that there are 15 wrecks sunk on the Cádiz coast. They went down with 4,000 men. Some of the ships that managed to enter the El Puerto de Santa María, without anchors or rudders, also sank. Many seamen were saved because local fishermen went out to try to save as many as they could.

I hope this in some way adds to the “classical” English descriptions that you can find. Reading through this text one is struck by the waste of life on both sides, and for what?

And the French, what did they think of Trafalgar?

Firstly, Napoleon wanted to invade England. But to do so he would need to control the English Channel for 36 hours, or at most 48 hours. So they needed keep the English fleet away from the Strait of Dover, for the time necessary for the invasion fleet to land.

To deceive the English fleet, La Touche-Tréville was to lure it far away to the Antilles to create a diversion and then return at full sail to Europe. With Gravina’s Allied and Spanish fleet from Cadiz, they would join Admiral Ganteaume’s fleet, which had been blocked at Brest. The strength of the French fleet would be 50 vessels, and they could cover and protect the crossing of the strait and prevent Nelson from cutting off communication with the continent.

But in August 1804, Admiral La Touche-Tréville, Napoleons best senior officer, died of a heart attack aboard the Bucentaure. Unfortunately all the admirals who had the qualities required to take over were either already assigned to an important command or did not enjoy the Emperor’s favour. The honour fell to Pierre-Charles-Jean-Baptiste-Silvestre de Villeneuve. Napoleon had referred to him as “the lucky man,” because in Aboukir, he had escaped without fighting. He was recognised as a skilled tactician, even if Napoleon had also said of him “I think this admiral doesn’t know how to command”. In any case, on December 19, 1804, Villeneuve arrived in Toulon and hoisted his flag on the Bucentaure. So, Villeneuve and the Bucentaure were ready to participate in a campaign that could change (and would change, but not in the way the French wanted) the course of history. In execution of Napoleon’s audacious plan, the flagship Bucentaure set sail with the squadron on March 30, 1805. On board the squadron were 6,330 troops under the command of General Lauriston, the Emperor’s aide-de-camp, charged with overseeing the execution of the instructions given to Villeneuve, in whom the Emperor did not have complete confidence.

Villeneuve complained about his ships, many of which were slow, the inexperience of his crews, and the defects in their armament. Villeneuve reported to Cádiz, where he joined Gravina and his division of six ships and headed to Martinique to find Missiessy. He failed, and fearing that Nelson would find him, he set sail back to Europe. Arriving on the Spanish coast, Villeneuve encountered Admiral Calder’s squadron near Ferrol and had a relatively successful engagement with them. But instead of continuing his journey, he returned to repair his damage in Cádiz, where he was soon blockaded.

Pressed by instructions from Paris that reached him in that port, he left with his entire fleet on 27 Vendémiaire (October 19) and the next day, near Cape Trafalgar, fought the battle that would decide the mastery of the seas for the next hundred years.

But was the battle really necessary?

The invasion of England was still feasible, but suddenly Austria and Russia were preparing to ally with England against France. The Emperor’s plans had to be modified and the invasion of England postponed. At the end of August, the Grande Armée left the camp at Boulogne and began its long march towards Germany. Just before leaving Paris to take command of his armies, Napoleon sent new instructions to Villeneuve stipulating that with the combined fleet, he was to land troops in Naples to prevent any English attempt to reinforce the Austrians from the south.

Villeneuve could even choose the date of departure. And once again, misfortune befell the combined fleet. Indeed, Villeneuve had also received news that Admiral Rosily was coming to offer him help and advice, but he soon learned that Rosily had in fact been sent to Cádiz to take command of the fleet. Rosily was already in Madrid, and as luck would have it, he was temporarily stranded there by a broken shock absorber on his carriage. Villeneuve, his honour hurt and feeling humiliated, decided against the advice of his fellow French and Spanish admirals and captains, to set sail and reach the Mediterranean, even at the cost of presenting battle to Nelson while he was still commander of the fleet. On the morning of the 19th, he left Cadiz. The pointless Battle of Trafalgar seemed inevitable.

The combined Franco-Spanish fleet went into battle in a classic line formation, but due to the inexperience of the crews and the difficulties in transmitting Villeneuve’s sometimes confusing orders, the formation as it stood when Nelson’s two columns approached was actually a crescent-shaped line with large gaps between ships, with some ships sometimes forming two or three ranks deep. The English fleet presented itself in two columns at right angles to the Franco-Spanish formation, aiming to penetrate the line as close as possible to the flagship and overwhelm it and the surrounding ships. This was an unorthodox maneuver that placed the leading ships of the columns in a position where they could not return their opponents’ fire. Therefore, it had to be carried out as quickly as possible. The experience of the English crews and the imprecise fire of the French and Spanish gunners ensured the success of this high-risk operation. Nelson was looking for the French flagship with the intention of engaging it in single combat, but he could not find any flag signalling an admiral, except for the one hoisted on the colossal Spanish Santissima Trinidad, a four-decker with 140 guns. Behind the Santissima, there was a French 80-gun ship and another 74-gun ship. These were the Bucentaure and the Redoutable. Admiral Cisneiros realised that Nelson intended to break through the line abreast of his ship and the Bucentaure. He reduced sail to slow the Santissima and close the gap between the two flagships, forcing Nelson’s Victory to pass under the Bucentaure’s stern, which proved fatal for the French ship. Passing beneath the elegant windows of Captain Magendie and Admiral Villeneuve’s rooms, richly decorated with mythological scenes, at the stern of the Bucentaure, the Victory unleashed a devastating broadside of 50 cannons, firing double or triple charges.

Cannonballs exploded the stern, disabling 24 guns, and wounding or killing half the crew. The Bucentaure never recovered from this terrible opening. At 14:00, its mainmast and foremast fell. Then the English ships Leviathan and Conqueror fired broadside after broadside into the French vessel’s flanks. Villeneuve called on the Santissima Trinidad to come to his aid, either to tow it or send a boat. But the Spanish ship, itself in the midst of combat, did not respond. At 14:05, the Bucentaure’s position was hopeless. Captain Magendie, in his report to the Minister of the Navy, wrote: “With the rigging torn away, dismasted, having lost all the men on the upper deck, the 24-gun battery completely destroyed and all the crew dead or wounded, the port guns covered by the rigging as they fell, with 450 dead or wounded, no longer able to defend themselves, surrounded by five enemy vessels and with no hope of rescue from anyone… there was no choice”.

He added that Admiral Villeneuve had no other option but to put an end to the carnage, in order to prevent the needless slaughter of even more brave men, which he did after three and a quarter hours of fighting and after throwing the wreckage of the Imperial Eagle and all the ship’s signals into the sea. The irony was that the only officer not injured aboard the unfortunate vessel was Villeneuve himself. Yet he had remained on deck throughout the entire engagement, seeking death, which would not take him. He had tried to reach another ship to continue the fight, but with all his boats destroyed and no ship responding to his request for assistance, he was unable to do so. Magendie reports how Villeneuve bitterly complained that amidst the carnage, not a single bullet was intended for him. And before lowering his colours, and as a funeral oration for such a fine ship, he exclaimed, “The Bucentaure has fulfilled its task, mine is not yet complete”.

The Bucentaure surrendered to a 74-gun English ship, the Conqueror. The ship’s log records, “At 14:00, we cannonaded and cut down the mainmast and foremast of the Bucentaure… We cut down the mizzenmast. At 14:05, the Bucentaure surrendered. We sent a detachment aboard to receive its surrender”.

It was Captain James Atcherly, a member of the marines embarked aboard the Conqueror, who was sent by her commanding officer, Captain Pellew, to receive the Bucentaure’s surrender. He went aboard with two sailors, a corporal, and two marines. He climbed aboard the imposing double-decker, unaware of the surprise that awaited him, for the Bucentaure no longer flew the vice-admiral’s ensign. His surprise was complete when, upon reaching the quarterdeck, he saw four high-ranking officers approaching him and presenting their swords. “One was tall, about 42 years old, and wore an admiral’s uniform”, then “The second was a French captain, Captain Magendie, who commanded the Bucentaure. The third was Flag Captain Prigny, Villeneuve’s right-hand man”. The fourth was a soldier, in the brilliant uniform, though stained by powder, of a Brigadier General of the Grande Armée, General de Contamine, in charge of the 4,000 soldiers aboard the fleet that day. General Lauriston, who had originally commanded the embarked troops, had already left the fleet and joined Napoleon in Austria, leaving command to his deputy, de Contamine.

“To whom,” the admiral asked in good English, “do I have the honour of surrendering?”

“To Captain Pellew of the Conqueror”.

“I am glad to have lowered the flag to the fortunate Sir Edward Pellew“.

“It is his brother, Admiral,” replied Captain Atcherly.

“His brother! What? Are there really two Pellews? Alas!”

Admiral Collingwood, in charge of the English fleet after Nelson’s death, was not to meet Villeneuve until three days after the battle aboard the frigate Euralyus. Here are his impressions of this first meeting, “The Admiral is a well-bred man, and I believe a very good officer. There is nothing in his manner of that aggressiveness and boasting that we attribute, perhaps too often, to the French”. And quoting Hercules Robinson from the Euralyus, Edward Fraser continues, “Villeneuve was a rather thin, tall man, a very quiet, placid Frenchman, who looked like an Englishman. He wore a frock coat with a high, flat collar, green velvet trousers with a band about ten centimetres wide, pointed half-boots, and a watch chain with long gold links. Magendie was a rather short man. He was a cheerful sailor who found a remedy for all his ills in the philosophy of the French, Fortune of War”. Although this was the third time he was taken prisoner by England.

The Bucentaure had lost 247 men. During the night, it broke the towline connecting it to the Conqueror and began to drift toward the shore. On board were two English officers and a few crewmen, along with the French survivors, their officers, and the corpses. Captain Prigny, wounded, and First Lieutenant Fournier, who was not wounded and had assumed command during the final phase of the battle, rightly decided to retake the ship from the English and attempt to save it. The English officers agreed to surrender rather than shed unnecessary blood. After makeshift repairs, the Bucentaure attempted to reach Cádiz. The night was dark, the rain was falling heavily, and the line could not be seen two meters. There was a local fisherman on board as well as three men who had been pilots, so Lieutenant Fournier handed them the helm. Finally, they sighted Cádiz and regained hope. But a sudden loud noise rang out, the Bucentaure had run aground. Despite attempts to lighten it in order to free it, for example by getting rid of the ship’s stores, it could not be saved. Prigny, after transferring all the living to a ship that had come to rescue it, gave the order for evacuation, and the Bucentaure almost immediately disintegrated with its cargo of hundreds of dead.

Admiral Villeneuve was taken to England as a prisoner of war. In the letter he wrote to the Minister of the Navy, he blamed no one other than himself, “So much courage and devotion deserved a happier fate, but the time has not yet come for France to celebrate successes at sea such as it has been given to experience on the continent. As for me, Monseigneur, overwhelmed by the misfortune and the responsibility that overwhelm me for such a disaster, I only wish, and as soon as possible, to lay at His Majesty’s feet either the justification for my conduct, or a victim that can be sacrificed, but not the honour of the flag, which I allow myself to affirm intact, but rather to the shadows of those who may have perished because of my imprudence, my lack of discernment, and the neglect of some of my duties”.

In October 1805 Napoleon wrote “Villeneuve is a wretch, a coward, an incompetent”. However, later when on Saint Helena Napoleon would write “Villeneuve was a brave man, but without character. He was dominated by circumstances. He shouldn’t have left Cádiz. I was the one who put him there. I thought he had more nerve”.

Released in April 1806, he stayed at the Hôtel de la Patrie in Rennes, awaiting orders. On April 22, he was found dead in his bed, his chest pierced by six stab wounds and the knife still lodged in his body. Was it murder or suicide? The Prefect of Rennes concluded “death due to self-inflicted injuries”, and the admiral’s body was buried that night, without any military honour. For a man who had sacrificed the lives of 4,400 French and Spanish soldiers and was responsible for the injuries inflicted on 2,500 others simply to avoid the humiliation of being relieved of his command, such a burial in the shadows may have seemed like simple justice.

Yet, many who have studied the unfortunate admiral’s life are prepared to grant Villeneuve mitigating circumstances. If we examine the French admiral’s attitude throughout the campaign leading up to Trafalgar, we realise that it is highly likely that the admiral was suffering from depression and should not have remained in command of the fleet at a time when it was being asked to accomplish a particularly difficult mission. Napoleon bears a heavy responsibility for having retained a leader they knew was no longer capable of successfully carrying out a mission with serious implications. Napoleon, even in his exile on Saint Helena, harboured a tenacious hatred for the man defeated at Trafalgar. Thus, for no other reason than his resentment, he raged against Villeneuve’s widow, for whom the Minister of the Navy had offered a pension of 6,000 francs, the same as that received by the widow of Admiral Bruix, whose husband held a rank equal to Villeneuve’s. Napoleon, with a stroke of his pen, reduced the pension by a third. Irrevocably associated with the name Villeneuve, the name Bucentaure alone was a constant reminder of the worst naval defeat suffered by France, and to paraphrase a French admiral in the 1950s about another French Trafalgar veteran, the Duguay-Trouin, which ended its career under the name Implacable and which England offered to return to France, “France has no use for a defeated ship”.

What became of Captain “Fortune of War” Magendie? After attending Nelson’s funeral, like Villeneuve, he left Reading, where he had been held prisoner on parole, in January 1806. He joined the Army of Portugal under General Junot and took part in the disastrous Portuguese Campaign. He was forced to surrender his naval division to British Admiral Cotton and once again surrender to the British. He retired on January 1, 1816, after 30 years of service, having taken part in nine campaigns, seven naval battles and two on land, held ten commands, and been taken prisoner five times by the British. He died in Paris on March 26, 1835, leaving no fortune to his widow. During his retirement at 9 rue La Fayette (Faubourg Poissonnière), Magendie led an obscure life and was not heard from again.

Napoleon had a generally contemptuous and disdainful opinion of sailors, especially the French, and even more so the Spanish, especially after the defeat at Trafalgar. In several letters and statements, Napoleon described sailors as “slow,” “timid,” and “disorganised”. He declared in 1805, after Trafalgar, “The navy is good for nothing. They are people without nerve, without energy.” In his remarks on Saint Helena, he wrote “The sailors lack the boldness and moral vigour of land soldiers. They lack decisiveness.” For him, the French sailors were individually courageous, but collectively incapable, poorly led, and ill-prepared, which made them an unreliable weapon. His opinion was even harsher towards the Spanish sailors, “The Spanish know neither how to manoeuvre nor fight at sea. They are dead weight.”

The reality was that Napoleon never deeply believed in maritime supremacy. He saw the navy only as a temporary instrument, to divert or divide the Royal Navy in preparation for an invasion of England. He firmly believed that the fate of Europe was decided on land, not at sea. Historians tend to now think that Napoleon did not understand naval logic (wind, line of battle, coordination, endurance at sea). His tactics were absurd for a sailor, but logical for an artillery gunner or land strategist.