My collection on Cádiz includes Cádiz I, Cádiz – II, Cádiz – Today (this posting), Cádiz – Maps, Models and the Camera Obscura, Cádiz – El Centro, Cádiz – El Pópolo, Cádiz – El Mentidero, Cádiz – San Carlos, Cádiz – Nochebuena and Nochevieja, and Cádiz – Trafalgar.

We are going to start with the excellent description of Cádiz provided by Wikipedia. It tells us that Cádiz is a city and port in southwestern Spain, and that it is the capital of the Cádiz province, one of the eight provinces that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

We are also told that Cádiz is the oldest continuously inhabited city in Spain and one of the oldest in western Europe. There is substantial evidence that the site was occupied in 800 BC by the Phoenicians, and it has been suggested that the city was originally called Gádir and might have been established more than 3,000 years ago. Traces of Phoenician settlements have also been found in El Puerto de Santa María and Chiclana de la Frontera (they naturally dispute the original site of Gádir).

Cádiz has also been the principal home port of the Spanish Navy since the accession of the Spanish Bourbons in the 18th century.

Wikipedia goes on to tell us that despite its unique site on a narrow slice of land surrounded by the sea‚ Cádiz is, in most respects, a typically Andalusian city with a wealth of attractive vistas and well-preserved historical landmarks. I would (to some degree) dispute this analysis. Attractive vistas, certainly. Historical landmarks, certainly. Well-preserved, I’m not so sure. They are certainly fighting the decay, but sometimes it looks like a battle they just can’t win.

The older part of Cádiz within the remnants of the city walls is commonly referred to as the Casco Antiguo (a pre-19th century town centre). It is characterised by the antiquity of its various quarters (barrios), which present a marked contrast to the newer areas of the city. Some of the oldest barrios are El Mentidero, El Balón, El Pópulo, La Viña, and Santa María. While the old town’s street plan consists of narrow winding alleys connecting to small plazas, newer areas of Cádiz typically have wide avenues and more modern buildings. Wikipedia is quite right to note that the city is also dotted with numerous parks where exotic plants flourish, including giant trees supposedly brought to Spain by Columbus from the New World.

Where is Cádiz?

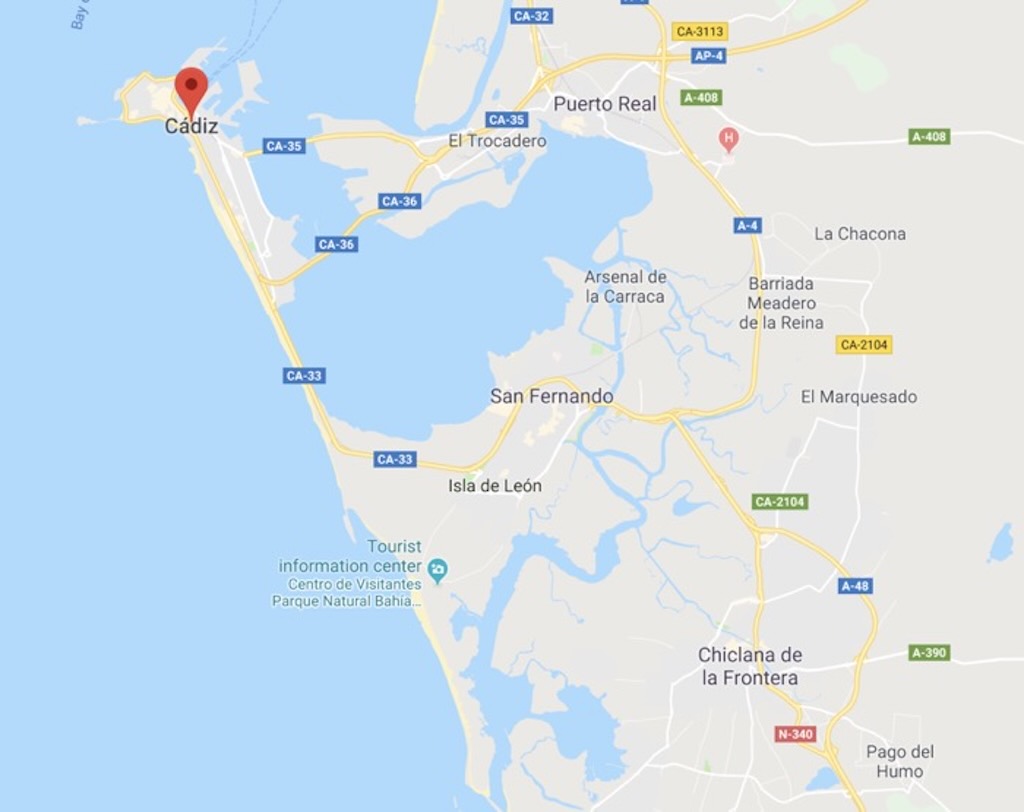

Today Cádiz, despite being the capital of the province, is only about half the size of Jerez de la Frontera, and it is now also just a bit smaller than Algeciras (see list of municipios). Figures differ depending upon the source, but the population is probably between 115,000 and 125,000. The problem is that the city is shrinking in favour of the residential-tourism towns nearby, e.g. Chiclana de la Frontera, El Puerto de Santa María, Puerto Real, Rota, and San Fernando.

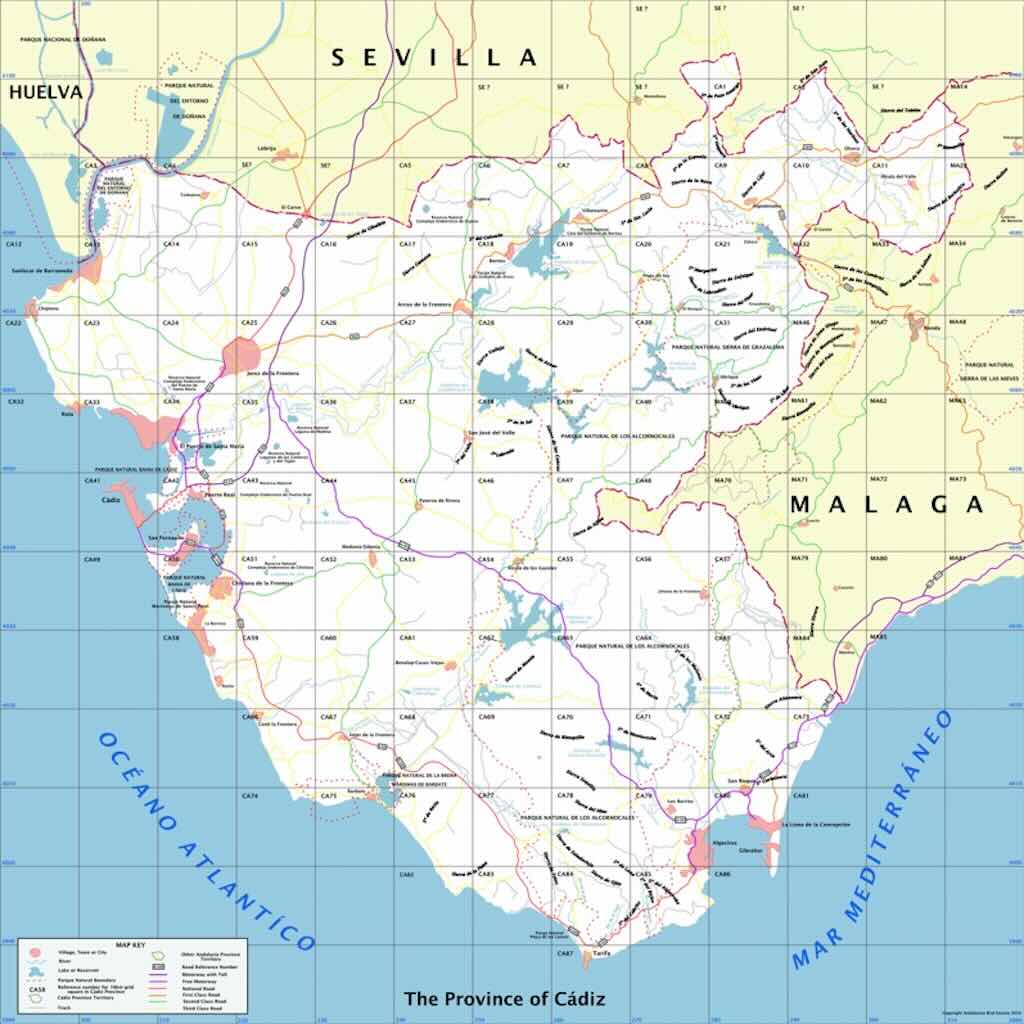

Below we can see the extent of the province of Cádiz, bordering on the provinces of Huelva, Sevilla, and Málaga. And of course we can see the Gulf of Cádiz (Atlantic Ocean), the Alboran Sea (Mediterranean Sea) and the Estrecho de Gibraltar.

We drove into Cádiz using the South motorway, the wonderful E5 that runs from Greenock and Glasgow, through Paris and Madrid, before arriving in Seville, Cádiz and Algeciras. We then turned towards San Fernando, that was once known simply as La Isla (The Island), and we passed by some of the most important beaches in Spain (e.g. Playa de Composoto, Playa de la Victoria).

When my wife and I visited Cádiz in 2014, the new bridge (see CA-35) to the city was not yet opened. We arrived on the CA-33 from San Fernando and not the CA-36 from Puerto Real.

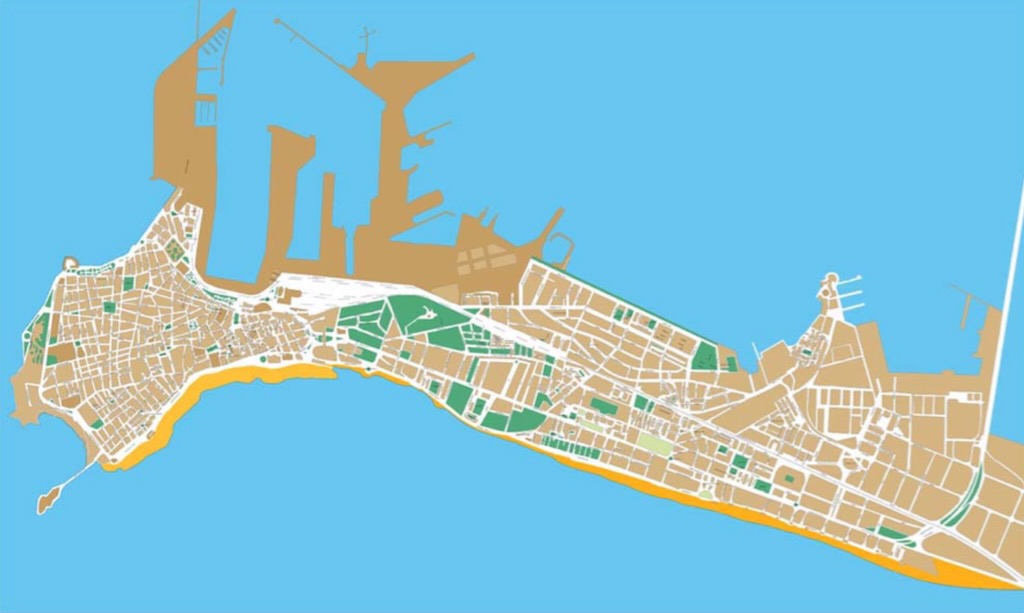

We then drove right through the newer part of Cádiz towards the old town, along the coast. In the below map we can see the ‘new’ Cádiz to the right (East), and the old town to the left (West). The route into the old town and to our hotel (the local Parador) took us in a clockwise direction around the South and West side of the old town. The ‘natural’ traffic flow looks to be along the South, or Atlantic side, around the old town in the clockwise direction, and back towards the East through the new Cádiz using the central boulevard.

Below we are going to look at Cádiz from a different perspective. Certainly one important element in the history of the city was when it replaced Sevilla as the home of the Spanish treasure fleet. In fact in the 18th century the sand bars of the Guadalquivir forced the Spanish government to transfer its American trade from Sevilla to Cádiz.

What we are seeing below is a recent example (2012) of the way the Guadalquivir became unnavigable. A heavy load of thick sediment was dumped into the Gulf of Cádiz (the colours are natural), and you can see the impact of the strong and complex currents in the region.

On the CA-33 we turned towards the Atlantic Coast, drove past San Fernando and the Isla del León to get to the Atlantic Coast. Historically, San Fernando developed on what was known as the Isla del León, however today with the urban expansion, road and rail construction, and land reclamation, it’s no longer an island in the strict geographical sense.

As we reached the Atlantic Coast we turned towards Cádiz at a place called Playa de Torregorda, and we saw the first beach-dunes.

We can see a white tower. According to Wikipedia this was originally a 17th century tower possible built on the remains of earlier observation and signalling towers. The older tower was demolished in 1898, but a new tower was built on the site in 1932. Apparently from 1805 to 1820 the tower was home to a military optical telegraph (like a semaphore telegraph), and from 1850 to 1857 is was a civil optical telegraph but according to a different principle. A certain brigadier Mathé installed a mobile sphere that indicated a numerical code, which was repeated from tower to tower by observing the codes using an achromatic telescope. I’ve read that Torregorda is (or was) a military base dedicated to shooting practice, and that the beach was at one time reserved for military and family members.

Driving towards Cádiz almost every practicable exist from the CA-33 leads to an official or unofficial beach. The next one along the road (seen above) is Playa de Santibañez, which whilst not officially designated, appears to be locally known as a nudist (or clothing-optional) beach.

Interestingly the above photograph Playa de Santibañez was associated with a comment about the nearby Via Augusta, which (according to Wikipedia) was the longest Roman road in Hispania, stretching over 1,500 km. Built and expanded under Augustus Caesar in the 1st century BC, it followed older Phoenician and Punic coastal paths, adapting them into a Romanised imperial road.

The road would have had to take the route of the dunes leaving Cádiz (Gades) for El Puerto de Santa María (Portus Gaditanus), then on to Jerez de la Frontera (Asta Regia and a major oppidum), Séville (Hispalis) before ending in Narbonne (Narbo Martius).

Next is the better known Playa del Chato, and then we arrive in the new part of Cádiz with the long Playa de Cortadura.

Beyond La Cortadura we hit the built-up area with Playa de la Victoria, a tourist beach about 3 kilometres long. This is the main beach for the holiday hotels in Cádiz, but all the other resort areas nearby have their own beaches as well.

As an extension of Playa de la Victoria and before entering the old town we also have the Playa Santa Maria del Mar.

As we approach the old town, in the distance on the left we can just about see the Playa de la Caleta, and just in front of it, sticking out into the Atlantic Ocean, the Castillo de San Sebastián.

It is said that La Caleta is unusual in that each of the major stones on the beach have names, e.g. la piedra cuadrá (the quadratic stone), la piedra reonda (the reonda), la palangana (the stone basin), la piedra del erizo (the hedgehog), la puntilla (the lace), la laja (the slab), etc.

Below we can see the old town from the other side. In front of us we have the Playa de la Caleta, and we can see the walkway to the Castillo de San Sebastián sticking out into the Atlantic Ocean. To the left of the Playa de la Caleta we have the Castillo de Santa Catalina, and a little further left the Parque Genovés. We can also see next to the Parque Genovés the modern Parador. And over the back we can just see the port of Cádiz.

Barrios of Cádiz

To understand what Cádiz was and is today, we must first understand the barrios of the Casco Antiguo (old city).

The word barrio originates from the Arabic barrī, meaning “of the land” or “outside,” and came into Spanish usage during the period of Al-Andalus (711–1492). It initially referred to areas on the periphery of a city or settlement and gradually evolved to mean any distinct neighborhood within a city.

Historically, barrios were defined by socio-economic, ethnic, or occupational distinctions. In medieval Spain, they often reflected guilds, religious communities, or immigrant groups. Over time, they also acquired a cultural and emotional identity, becoming centres of local pride.

Initially Cádiz depended upon many small orchards (huertas) that had slowly been united into cottages and country estates (casas de campo y residencias). So for the richer land-owner the house in the city centre was often used just for weekends and holidays, thus the importance of gardens and open spaces. The extramuros would come into the city for the coffeehouses, shops and taverns (cafetines, ventas y tabernas) that opened around the city gates (puertas).

So the barrios nearest the city gates housed mostly farm workers (trabajadores del campo). In 1865 almost half the population of Cádiz were farm workers. Another 20% were workers paid on a day-by-day basis (tanners, potters, millers, moulder’s and finisher’s in the iron foundry’s, those making and selling food and wine, and shop-workers). The rich were buying their houses in the better barrios, but throughout the 19th century it was relatively easy to move from one part of the city to another. Everyone tried to move nearer to the centre and to buy entire 3-floor houses for their extended families. Those families who wanted to stay in the same barrio, moved from the narrow side streets to the wider through-streets.

Cádiz’s barrios began forming organically in the densely populated peninsula. Key early neighbourhoods like El Pópulo (oldest, near the Roman theatre) developed within the city walls and were often fortified. Santa María and San Juan emerged with strong Afro-Andalusian and working-class identities. In the 18th–19th centuries, Cádiz flourished through trade with the Americas, and new barrios like La Viña formed westward to house dockworkers and fishermen. These areas were known for their communal life, religious brotherhoods (cofradías), and later, flamenco culture. There is a list, dating from 1830, which re-grouped different earlier barrios into five districts, namely “Nuestra Señora de la Bendición de Dios”, “San Carlos”, “San Lorenzo”, “Nuestra Señora de la Palma”, “Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria”, and “Santa María”. For example San Carlos included five barrios, namely “Nuestra Señora del Pilar”, “Nuestra Señora de las Angustias y San Carlos“, “Nuestra Señora del Rosario”, “Barrio de la Cuna”, and “Barrio de San Felipe”.

For example, the barrio La Palma was newly built in the 18th century (it was often also called the barrio del Mundo Nuevo) and from 1749 it started to build into the older barrio Hospicio. Both were “poorer” because of the humidity, but houses were lower, streets slightly wider, and they ‘let-in’ more sun. With time this barrio became attractive to both the richer professional and civil servants. Another barrio, La Merced, was home to sailors and fishermen, as well as carpenters, shoemakers and daily workers. This barrio would slowly join with the another antigua barrio, El Pópulo. And with time it would also attract a few important and rich owners, even as it became an ‘exotic’ mix of taverns, wine cellars and English slave owners (already installed in the barrio in the late 17th century). Also over time the barrio La Palma finally became fully integrated in to the barrio we know today as El Pópulo. A barrio that still retains the three gates to the original medieval city, namely El Pópulo, De la Rosa and De los Blancos Arches.

Throughout the 19th century the names and extent of the different barrios changed, and they only started to be “standardised” in the late 1880s. Also the urban area of Cádiz extended beyond the city walls, but these people were just called extramuros. In 1868 the city was divided into quarteles, each with its own internal ‘government’ and police, and each was divided into smaller barrios. The quarteles were called Santa Cruz (including San José), Roasario, San Antonio and San Lorenzo. And the barrios were at that time called Escuelas, Pópulo, Merced, San Carlos, San Francisco, Correo, Constitución, Hérclues, Cortes, Las Palma, Hospicio, and Libertad. The last two were the most popular, but the rich and powerful lived in San Carlos, San Francisco, Correo, Constitución, and Cortes. The poorest barrios were Las Palma, Hospicio, and Merced (and of course the extramuros).

In the 20th century, urban expansion beyond the historic peninsula led to planned neighbourhoods outside the old walls, such as El Cerro del Moro and Loreto. Today the city of Cádiz is divided into 10 municipal districts (distritos), created primarily for administrative purposes by the Ayuntamiento (City Council). These districts span two distinct areas, firstly the historic peninsula (Casco Antiguo), and also the modern expansion on the isthmus connecting Cádiz to the mainland. These divisions are primarily for municipal governance and don’t always reflect the historical and cultural boundaries recognised by locals. I could not find a definitive public list that includes all historically recognised barrios within the administrative districts.

It is possible to look at almost any early barrio and see how it evolved (or was absorbed) into those we know today. To close this part we will just mention the most obvious changes. Originally the richest barrios were San Carlos, San Francisco, Correo, Constitución, and Cortes. Today the old San Carlos, San Francisco, Correo, and Constitución (along with a bit of Hérclues) are all now known as the barrio San Carlos.

The end result of these changes was that the barrio San Carlos, the most protected from the winds, became the richest (and to a lesser degree this is also true for the barrio El Bálon). The poorest, or most popular, barrios were those most open to the Atlantic ocean, e.g. El Populo, San Juan and La Viña.

In the 21st century, gentrification, tourism, and cultural heritage initiatives have reshaped historic barrios. Districts 1, 2 and 8 form the Casco Antiguo, entirely located on the peninsula (the narrow, walkable part of Cádiz surrounded by water).

So here a few of the more important barrios, namely:-

- El Pópulo, the oldest barrio, is a maze of narrow streets and historic landmarks, including the Roman Theatre and the Cathedral. It’s considered the birthplace of the city. The name derives from the Latin phrase “Ave María, ora pro populo” (Hail Mary, pray for the people), inscribed above the Arco del Pópulo, a medieval gate leading into the neighbourhood (the other two gates are La Rosa and Los Blancos). The Café Teatro Pay-Pay is often mentioned, originating as a lively venue in the 1940s and experiencing a renaissance in 2001 as a hub for flamenco and theatre.

- La Viña, located near Playa de la Caleta, is the epicentre of the city’s famous Carnival celebrations. As far as I know the name comes from the vineyards (viñas) that once occupied the area. I think La Viña was born out of necessity. Far from the port, the local bourgeoisie ruled out that area as a place to settle, so it was left to fishermen and the poor.

- Santa María, a historic barrio with deep flamenco roots, is characterised by its traditional Andalusian architecture. I think the name simply comes from the Iglesia de Santa María.

- San Juan, has its own identity determined by its proximity to the port area. I think the name comes from Iglesia de San Juan de Dios. It’s just a handful of streets, but is said to have been the first port in the history of Cádiz, the Phoenician port. During recent excavation work they discovered a dry dock carved into natural rock, where the warships of the Phoenician fleet were built, and which played a fundamental role during the Second Punic War. Also one of the first organisations of working-class women was born there in June 1918, the Sociedad de Cigarreras de Cádiz (Cádiz Cigar Makers Society).

- San Carlos, is an 18th-century planned district, known for its neoclassical architecture and the Monument to the Constitution of 1812 in Plaza de España. The name comes from Carlos III.

- El Mentidero, centred around Plaza del Mentidero, is close to the Gran Teatro Falla. In the mid-18th century, the Cofradía del Santísimo Cristo de la Expiración established a humilladero (a type of wayside cross or shrine) in this plaza, which was named Cruz de la Verdad (“Cross of Truth”). However, the name took on an ironic twist. The plaza became a popular gathering spot where locals would share gossip, rumours, and unverified news. Due to this reputation, the area was colloquially referred to as the Plaza de la Cruz de las Mentiras (“Plaza of the Cross of Lies”), and eventually, it became known as the Plaza del Mentidero (“Plaza of the Gossip”). I’ve seen mention of a pharmacy, which became a meeting point “for men in hats”, who told news and fables, bluffing, and gossip. Originally I think it was an area of old orchards before its construction in the 18th century.

- El Balón, adjacent to Mentidero, is a compact area home to the local university. There was a small square where pelotaris played the game of pelota. A type of Basque pelota in which the ball was thrown, but it is unclear whether with a racket or a type of basket. From that sport, the square was named “El Balón“. However, originally, it was known as the Plaza del Huerto de la Tinaja or the Lost Garden. Before that, the area, being far from the rest of the population, served as a depot for powder magazines. The area was home to the first hot-air balloon flight in Spain, to the most dangerous bullring in Spain due to its narrowness, and to the Electricity Factory, which made Cádiz the first capital in the country with electric lighting.

- La Catedral, surrounds the Cathedral of Cádiz, and has a mix of religious and civic architecture.

- El Mercado, home to the Central Market (Mercado Central de Abastos), is a hub for gastronomy, offering a variety of fresh produce and local delicacies.

- San Francisco, around the elegant Plaza de San Francisco, is known for its neoclassical buildings, and its rich history tied to the liberal movements of the 19th century.

- San Antonio, centered around Plaza San Antonio, is characterised by its 19th-century architecture.

- La Caleta, known for its beach, is closely associated with La Viña and is home to the Castillo de Santa Catalina.

Casco Antiguo

The “Tacita de Plata” (one old nickname for the city) is considered the oldest city in the Western World. It was founded (possibly as early as 1100 BC) by the Phoenicians, a seafaring people who turned Gadir into an important trading colony where the Carthaginians, the Romans, the Visigoths and the Muslims would all subsequently settle. An open, cosmopolitan city, its port was chosen by Columbus as the point of departure for his second voyage to the New World. The city would then become, after the decline of Seville, the port to The Americas, hosting trade with the American Continent. This frantic commercial activity brought about an era of economic and cultural splendour, when Baroque palaces were built each with their characteristic towers offering amazing views out to sea.

El Centro

I must admit I’m not even certain if the barrio El Centro actually exists. I can find little that defines it, but there are real-estate offerings that mention the barrio. Many articles mention La Viña, El Pópolo, Santa María, and El Mentidero, and ignore San Carlos, El Balón, San Juan, and El Centro. So I am going to simple define El Centro as being made up of everything that people don’t bother mentioning in the other barrios. This means places like Paseo de Canalejas, the Muelle Ciudad (the city docks), the Iglesia de San Agustin, the Iglesia de San Pablo, the Casa-Palacio de Mera, the Museo de las Cortes de Cádiz and the Iglesia Oratorio San Filipe Neri, and the Torre Tavira.

We are going to start our visit to this particular barrio with a quick walk down Calle Ancha (which could be translated as Broad Street). It runs south-east from Plaza San Antonio. It is in fact wider than other streets in the city and was (and still is) a kind of high-street with some shops and elegant residential buildings. Being in a pedestrian area it is still today a preferred street for gaditanos to stroll along.

All the guide books tell you to look out for the Iglesia de San Pablo and the Casa-Palacio de Mera. They will tell you that the church was built in 1678 and was rebuilt in a Neoclassical style in 1787. I never managed to visit this church, it was always closed. However it is said that it has an impressive Italian built altar from 1791, with an impressive Cristo del Ecce-Homo (see below). The Casa-Palacio de Mera was also always closed and I must admit looked a bit run-down. As far as I can understand things, a very rich man was able to buy a total of seven existing properties (three in C/Ancha), and build a new mansion in the so-called estilo Isabelino (between late Gothic and early Renaissance). Inside it is supposed to have a majestic double staircase, lots of columns in Carrara marble, galleries, and a secluded courtyard garden.

The Iglesia de San Agustín was built between 1617 and 1647 and started out life as a convent, cloisters, church, and gardens, etc. The façade is one of the best examples of the Mannerist style in Cádiz. The interior is more Neoclassical, and it is home to a very impressive Cristo de la Humildad y Paciencia.

Down by the Muelle Ciudad (the city docks) there is the Paseo de Canalejas. From what I can understand the garden area has just become accessible again after being closed for three years (building an underground parking). However the paseo in fact existed well before 1773. In those days it changed name quite frequently, one such name was “la pegada a la muralla” or something like “keep close to the wall”. From 1773 it was just “la de la Aduana” or “the way to the customs house”. It finally got a decent name in 1890 when it acquired the gardens and when the fortifications were removed for the development of the port.

Whilst we were in Cádiz there were a couple of day when everyone appeared to speak Italian! This was because a major Italian cruise ship called the Costa Fascinosa had docked (along with its 3,780 passengers).

The Iglesia Oratorio San Filipe Neri (above) is yet another Baroque church built between 1685 and 1719, and later repaired after the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. The façade is quite unusual because it is covered with commemorative plaques to the many people who gave birth to Constitución Española del 1812. As far I can see the church was home to the development of the Constitución between Feb. 1811 and Sept. 1813.

During the later uprising ‘Trienio Liberal‘ in 1820 people were killed, and in 1843 their remains were placed in this church. Las Cortes also met again in this church in 1823 during the siege that ended the “Trienio Liberal”. In 1912 the tombstones in the crypt were placed on the façade of the church. As far as I can understand the story, the re-introduction of the Constitución had been decided in Madrid in 1820, and on 10 March 1820 people were out on the streets in Cádiz. However the local garrison were not supporters of the constitution, and they attacked the people in the streets around Plaza San Antonio. Sixty-one men and ten women were killed to shouts of “Viva el Rey”. There was looting and some houses were burned before the army were formally told that Fernando VII has accepted the Constitución. Later the Cádiz army swore allegiance to the Constitución and attended the funerals, but they went unpunished.

Museo de las Cortes is right next door to Iglesia Oratorio San Filipe Neri. The museum was opened in 1912, but was closed in 1947 due to damage from an explosion. It was re-opened in 1964, and has been undergoing modifications ever since.

The explosion was of 200 tons of trinitrotoluene (TNT) in the powder magazine of the navy (mostly 1,600 torpedoes and depth charges and including some WW I munitions). The cloud was visible in Ceuta, Huelva, Sevilla, and even in Portugal. The old city was saved by the old defensive fortification and the Puerta de Tierra. The explosion killed 150 people, injured 5,000 people, destroyed 500 buildings and damaged another 2,000 (locals have always claimed that the deaths and damage was considerable more than indicated in the official figures). The explosion also cut the local rail link, water mains, and phone lines. The most logical explanation is the instability of old guncotton, but naturally many people still claim that it was an attack on the Franco dictatorship.

Anyway back to the museum. The most impressive thing on show is the very large Maqueta de Cádiz. It all started with Carlos III de España (1716-1788) ordering models of all the strongholds in Spain, but only the one in Cadiz was ever finished. Infantry Lieutenant Colonel Alfonso Jiménez, helped by some gaditanoscabinetmakers, made the model between 1777 and 1779 (it was restored between 1950 and 1962). The model covers a surface of nearly 13 x 7 m, and is made up of 333 separate pieces.

Our last visit in this barrio will be to the camera obscura in the Torre Tavira. It is a great tourist attraction, and provides the visitor with an excellent overview of the city.