My collection on Cádiz includes Cádiz I, Cádiz – II, Cádiz – Today, Cádiz – Maps, Models and the Camera Obscura, Cádiz – El Centro, Cádiz – El Pópolo (this posting), Cádiz – El Mentidero, Cádiz – San Carlos, Cádiz – Nochebuena and Nochevieja, and Cádiz – Trafalgar.

El Pópolo is the oldest barrio in the historic centre of the city. I could not find an exact definition of this barrio. But as far as I can see it touches the barrio San Juan, runs along C/Campo del Sur to the Puertas de Tierra, back west along C/Sopranis, goes around the back of the Ayuntamiento, and back to Catedral, but (oddly) excludes Plaza de la Catedral.

The key attractions in this barrio include, the Catedral, the Iglesia de Santa Cruz (Catedral Vieja), the Teatro Romano, the Museo Taller Litografico, the Baluarte de San Roque, the Puertas de Tierra, and the Parroquia de la Merced. I have also seen the Puertas de Tierra included in the barrio Santa María.

Of course we have to start with the Cathedral, or to give it its full name, La Santa y Apostóloco Iglesia Catedral de Cádiz. In fact it is the 2nd cathedral, the first is just next door and is now called the Iglesia de Santa Cruz. So the “new” cathedral was started in the Baroque style in 1722, but it was finally finished in a Neoclassical style in 1838 (and I’m certain someone tried to put a little Rococo in there as well). Why build a new cathedral? Well, it was all about showing off. When the operational rights of the Casa de Contratación were moved from Sevilla to Cádiz in 1717 they though the old cathedral was to small for them.

Building over such a long time does not just involve changing from one style to another and one builder to another, but also from one economic situation to another. The building is a mix of “Genoese marble” and jasper, mixed with limestone and oyster stone (piedra ostionera). The oyster stone is a porous sedimentary rock made from the remains of seashells. It is widely used in Cádiz and the local region, and they often talk about an ostión, a kind of big oyster. The stone is very porous, rapidly acquires a rough surface, and is a kind of boring light-brown colour.

Genoese marble is not a specific geological category of marble, but rather a term used historically and commercially to refer to types of marble that were quarried, processed, traded, or widely used in and around Genoa. So this could include:-

- Portoro marble (or Portoro nero) a luxurious black marble with gold veins, quarried in Porto Venere (southeast of Genoa, near La Spezia). Genoese traders controlled much of this marble’s trade.

- Rosso Levanto, a dark reddish-purple marble with white veining, found in Levanto.

Green Ligurian marble (a breccia or serpentinite often called verde antico). Often found in Genoese churches and exported.

But also Genoa, like Venice, was a major marble-trading hub in the Mediterranean, particularly from the 12th to 18th centuries. They imported white marbles from Carrara and the Apuan Alps. They traded Greek and North African marbles, including ancient Roman spolia. And they exported marble products (e.g. columns, altars, tomb slabs) to Spain, southern France, and Latin America.

So back to the cathedral. The first thing you notice on entering the building is that the ceilings are all netted to stop stones and bits falling on visitors. The decay through age, seawater erosion, and poor building materials all play a part. As with many churches in the city, the walls are plain white stone, and the alters and chapels are in an ornate Baroque style.

There were two things that caught my attention. The first was a massive processional “custodia en plata” or silver monstrance. Made in 1664 it is nearly 4 m tall and weighing more than 300 kg. The “cogollo” or heart of the monstrance dates from the 15th century and is Flemish in origin, and sits in the lower of three sections. The silver base of three sections dates from 1692, and silver covered “cart” on which it all sits dates from 1721. It is just the 3 upper sections that weight 300 kg, and when part of an Easter pasos it requires 12 men to lift it.

The second thing that caught my attention was the crypt under the main altar. The picture is not very good, but I think you can see that it is impressively big. A major engineering feat for something finished in 1732.

One of the “occupants” is a girl about which there are a number of legends (e.g. hit by lightning during her communion). The reality is almost as interesting. In 1812 the Bishop was looking for ways to attract people to the cathedral. Over the years gaditanos had become more liberally inclined, and church attendance suffered. A friendly Bishop from Tusculum gave him a sacred relic, the body of Saint Victoria, virgin and martyr, provided by Pope Pius VIII from the old Catacomb of Priscilla. The body was dressed in the style typical of a Roman noble woman. A blood sample was in a gilded and painted wooden urn, closed and sealed. However, during that period there was an active market in such relics, and people would make “catacomb martyrs” of dubious origin. The trade in fake relics became so common that the Vatican was forced to intervene. Still this piece of marketing worked, because it is reported that attendance in the cathedral increased again.

The Saint Victoria in the crypt is suppose to be the Roman martyr Saint Victoria of Albitina, who was martyred in 250 AD during the reign of Emperor Decius. She is known for her steadfast faith and is commemorated with a feast day on February 11. Her relics are displayed in a glass urn, with her face, hands, and feet covered by wax masks, a traditional method used to preserve and present relics of saints.

The crypt, located beneath the main altar and below sea level, also houses the tombs of notable figures such as composer Manuel de Falla and writer José María Pemán. This architecturally unique space is known for its distinctive acoustics, where it is said that the sound of waves can be heard reverberating through its walls.

One of the most iconic sights of Cádiz is the back view of the cathedral with its dome covered in gold coloured glazed tiles.

Almost next door is the Iglesia de Santa Cruz, or Catedral Vieja. As we have already said, this was the city cathedral until 1838, whereupon it was “demoted” to a parish church. It is thought that the church was built in around 1262 on the remains of a mosque (and possibly an even earlier Christian church). It would have been pure Gothic, but during one of the many battles in and around Cádiz an Anglo-Dutch force sacked the city and burnt the church in 1596 (it probably had a wooden roof at the time). So what we have is a “new-build” dating from 1603. I must admit it looks very ordinary from the outside, with the separate 15th century bell tower.

Back in front of the “new” cathedral, we are in Plaza de la Catedral. As we look around we can see that it is one of the biggest squares in the city. We can also see the so-called Arco de la Rosa, in the south-east corner, and in the north-west corner the Iglesia di Santiago.

The Arco de la Rosa is one of the oldest gates in the old city walls. Today it gets its name from a small chapel for la Virgen del Rosario de los Milagros (by 1761 it had become Nuestra Señora de la Rosa). Originally there would have been two narrow arches (making a barbican) offset making it easier to defend. In fact the original name was Puerta de Santiago, because it provided access to the old barrio Santiago. The remaining arch was later widened to allow carriages to pass into the square. Until the 19th C the arch opened into a small square called Plaza de las Tablas, where the gallows were located. The gallows and the small square were removed when the “new” cathedral was opened.

In 2014 the Teatro Romano was closed to visitors. This site was only discovered in 1980, but we know that it had already been abandoned in the 3th century and sacked in the 4th century. It would appear that the Muslims build part of the cities defensive walls on top of it. Today it is said that a substantial part of the original Roman construction has been built on, making it impossible to recover completely (but we know it was still visible in the 16th century).

It would appear that the original theatre would have been massive, 120 m across and able to seat 20,000 people (in a city of 50,000). They also claim that it is the oldest and largest Roman theatre in Spain. It was such an important venue that there are writings describing the way the first 14 rows of seats were reserved for city nobles, and that one poor actor was actually executed because the crowd did not like his acting.

There had been stories that when digging wells they found areas underground with marble seats, etc., but the actual theatre was only “discovered” in 1980. It is also evident that a lot of medieval buildings were partially built using stone taken from the theatre. The Wikipedia article on this particular Roman theatre provides also a good description of the layout of a typical Roman theatre. However, the reality is that the site was closed, and it looked as if it had been closed for some considerable time, and will probably stay closed. It was impossible to see anything of interest.

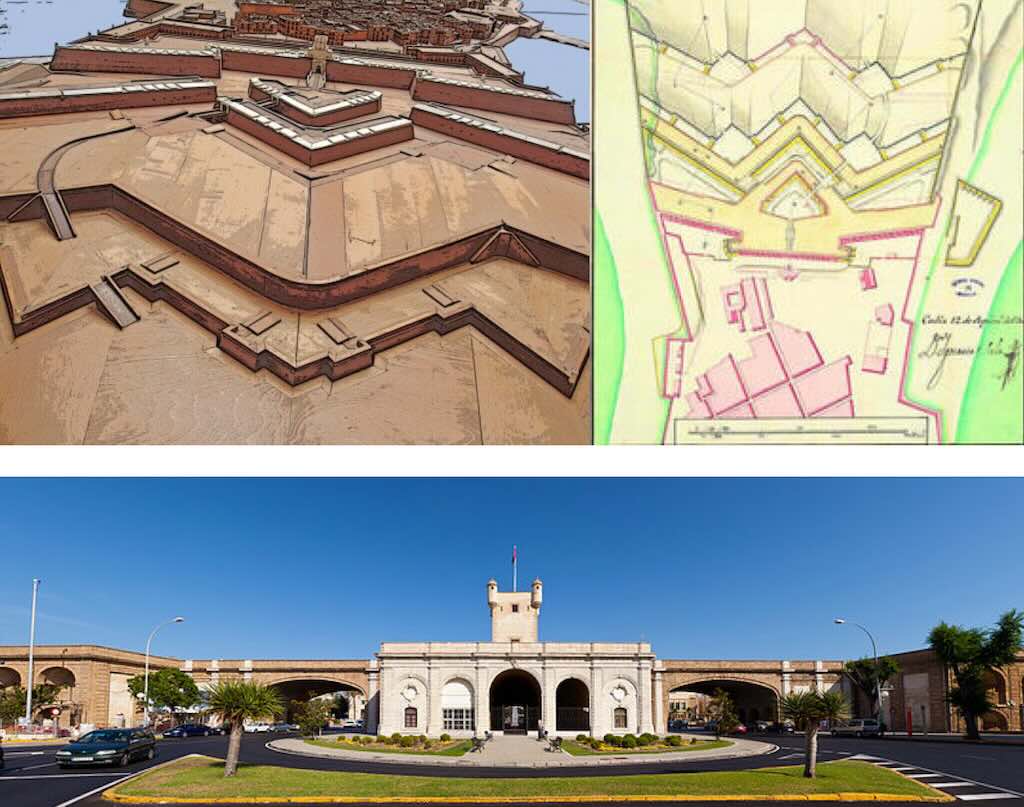

So now we get to the Puertas de Tierra. The first wall of the city was built in the 15th century, and in 1574 it was extended with two bastions. In 1756 it was extended, and a central building in marble was added. The fortress wall separated, and still separates, the old Cádiz from the new or extramuros Cádiz.

A central tower (originally called “Torre Mathé” but now often called simple the Torreón) was added in 1850, and there was even an optical link established between Cádiz and Madrid which could transmit messages in 2 hours.

Early in the 20th century part of the fortress was demolished to create additional building space. It is worth noting that the wall still worked as a defence in 1947. A major explosion occurred in a military ammunitions store outside the walls. More than 150 people were killed and 500 buildings seriously damaged, but the wall saved the old city from the blast. Above we can see the extent of the original wall, and below the present day fortress.

They say that as you enter the barrio El Pópulo, you feel the very pulse of history. Its arches lead you to places where Phoenicians, Punics, Romans and Arabs once lived and worked.

There is a bit of truth in what they say!