The view on entering the bay of Cádiz presents the finest collection of objects that can be conceived. On one extremity of the left point is situated the town of Rota, a little further the castle of Santa Catalina and the neat city of Santa Maria. At a greater instance, on the lap of a lofty hill, stands Medina, nearer the sea the town of Puerto Real and the arsenal of the Carracas, and on the extremity of the right hand point of land the city of Cádiz.

To add to the splendour of the scene, this extensive bay was filled with the vessels of different nations displaying their respective colours amidst a forest of masts. The whiteness of the houses, their size and apparent cleanliness, the magnificence of the public edifices, and the neat and regular fortifications form together a most striking assemblage of objects.

Travels in the South of Spain

letters written in 1809 and 1810 by William Jacob, Esq.

Introduction

In 2014 we decided to visit Cádiz for Christmas and the New Year. We visited one of the oldest cities in Europe, and at the same time we learned more about how the Spanish celebrate one of the most important festivals in the Christian calendar.

I must admit that my intention was to rapidly describe here our visit to a city that had (I foolishly presumed) a limited role in history. I expected to have to dig deep to find a few high-points to get us from the pre-history to today’s consumer society. A fine idea, but as I delved into a variety of sources I found one layer of history upon another. Cádiz is a real “been there, done that”. Phoenician, Greeks, Romans, Visigoths, Moors, the discovery of the Americas, the Catholic Monarchs, Trafalgar, the first Spanish Constitution, it has all happened in Cádiz. You will find here, and in a collection of related pages, quite a variety of bits and pieces, and I already apologise if my text does not read like a professional ‘novela’.

My collection on Cádiz includes Cádiz I (this posting), Cádiz – II, Cádiz – Today, Cádiz – Maps, Models and the Camera Obscura, Cádiz – El Centro, Cádiz – El Pópolo, Cádiz – El Mentidero, Cádiz – San Carlos, Cádiz – Nochebuena and Nochevieja, and Cádiz – Trafalgar.

So let’s begin our roller-coster of a history….

Cádiz is said to be one of the oldest, if not the oldest, town still standing in Spain and probably in Western Europe.

We will start by clarifying the exact ancient name for the city:-

- Gadir (גדר or Gádir), or eventually Gaddir, was the original Phoenician name for Cádiz

- In Greek the city was known as τὰ Γάδειρα or Gadeira, which some sources say is preserved in the form Cádiz or Cádix (Cádix being the plural form because the city stood on a set of islands)

- Gades, Gadesium, Gadis, and Gaddis are the Latin forms for Gadir, and later the city was called Gaditanus

- Qādis in Arabic, and some (other) sources say Hispanicised as Cádiz.

A Phoenician City

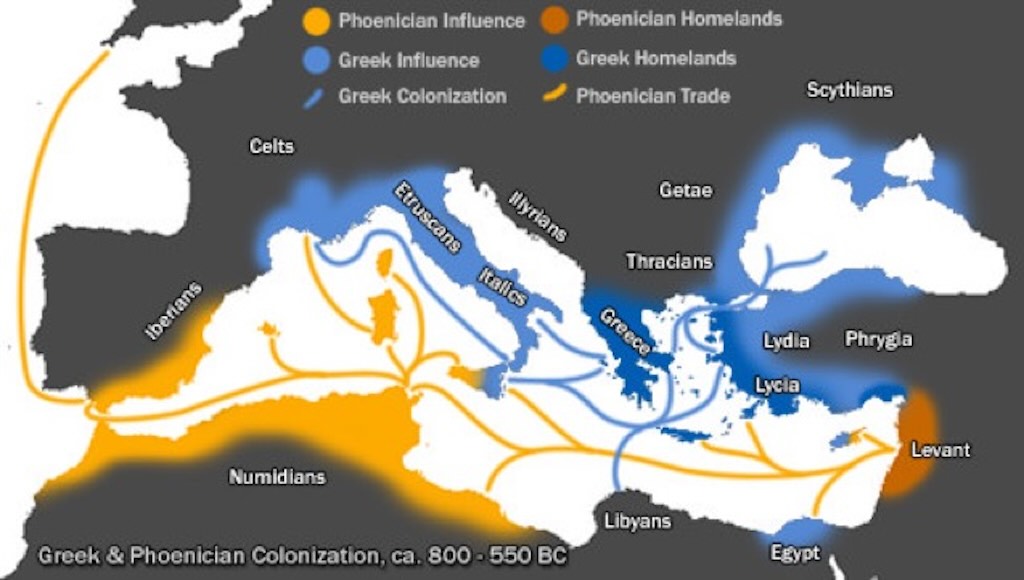

We are told by Greek writers that Gadeira was founded by the Phoenicians from Tyre (Lebanon). And today we still call people coming from Cádiz, gaditanos. Experts have put a date on this, 1104 BC, although the oldest remains in the city date from only 800 BC. We know Tyrian merchants were the first to navigate the Mediterranean and they founded colonies along the coasts of Greece, southern Italy, the northern coast of Africa, Sicily, Corsica, and in Gadeira (Cádiz).

For example experts think that they placed at the end of the island of Cádiz a temple dedicated to the god Melqart, the tutelary god or guardian spirit of Tyre. We know of only two other similar temples, one in Ibiza and the other in Cartagena.

We also know that Hannibal was a faithful worshiper of Melqart, and there is a legend that says that just before setting off on his march to Italy he made a pilgrimage to Gadir, the most ancient seat of Phoenician worship in the West.

This is a votive statue of Melqart found in 1984 on the small island of Sancti Petri, the possible location of the Melqart sanctuary. I must admit it looks a bit ‘Egyptian’ and it has been suggested that Melqart might have been originally derived from the Canaanite deity Resheph (and thus back to the Theban war god Montu).

The reality is that the Phoenician colony was established before the beginning of classical history. What we know is what the Greeks wrote several hundred years later (from 7th century BC). Those same Greek authors would also talk about the Melqart temple having two bronze pillars with inscriptions mentioning the expenses incurred by the Phoenicians in their making. The temple was later renamed by the Greeks and Romans as ‘Hercules Gaditanus‘, and became well known as an oracle.

Phoenician coins have been found in Cádiz. They were copper and usually bore the head of the Tyrian Hercules (Melqart or Melcarth wearing a lion’s skin headdress) on the obverse, and on the reverse one or two fish and the Phoenician epigraph Agadir or Hagadir (which would have been pronounced as Gadir, and is said to have meant fortress or walled area).

We know that the region was already occupied in 3500 BC (Neolithic), and this cylindrical idol from the Copper Age (around 2500 BC) was found just along the coast at Sanlúcar de Barrameda. This type of artefact has been found all over western Andalusia.

For the Greeks and Romans Gadeira was the western-most point of the known world, beyond, the seas were not navigable. The island on which Gadeira stood was traditionally identified as Erytheia, where Geryon fed the oxen that were carried off by Hercules. The Greeks were really good in creating a bit of mythology, so they promoted the idea that Hercules founded Gadeira after performing his tenth labour, slaying Geryon the monster with three heads and torsos joined to a single pair of legs. They even identified a tumulus near Gadeira as Geryon’s final resting-place. Much later Cicero suggested that human sacrifices were made there, others mentioned a shrine to the cult of the dead.

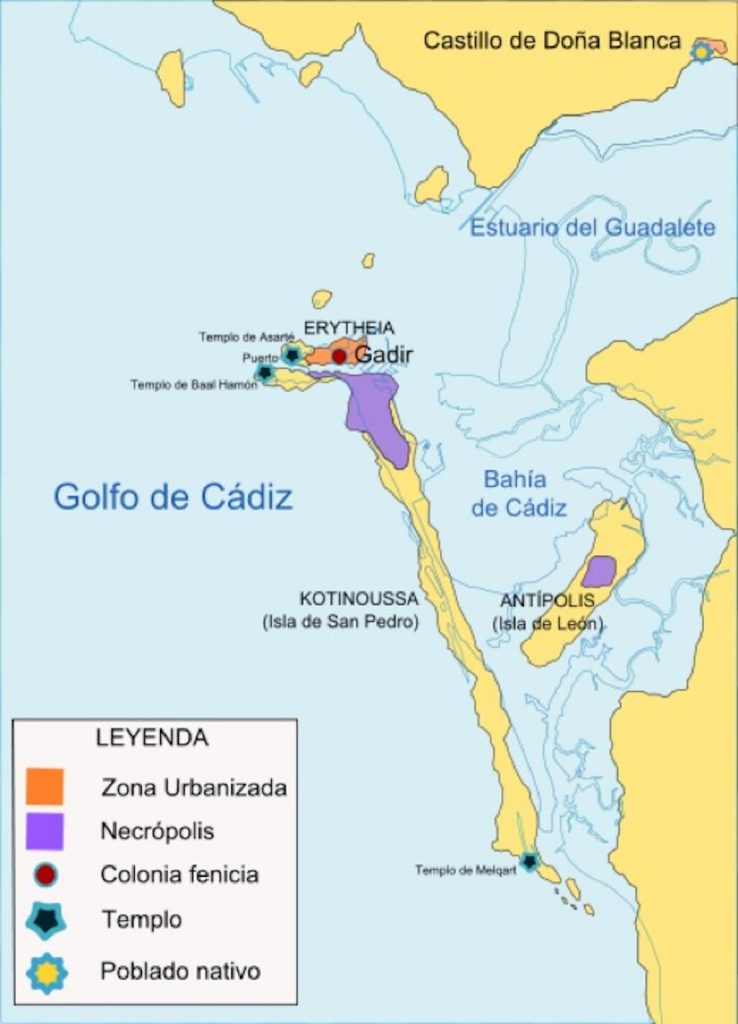

The reality was that Gadeira was an archipelago of islands, and already the confusion started there. One source talks of Erytheia and Kotinoussa (Isla de San Pedro) being joined to make the island of Gadir, and another island Antípolis or the Isla de León (which was renamed San Fernando in honour of Fernando VII in 1813). Another source considered Erytheia the same as the Isla de León (but also said it might have been called Aphrodisias) and even suggested that it is now the city of Cádiz. And naturally almost everyone agrees that Cádiz was founded on Erytheia, but they appear to talk about different islands!

And just to make things truly confusing, others think that Cádiz or Gadir was really on a small separate island called Krónion at the end of Kotinoussa, where there was a temple dedicated to Kronos (or Ba’al Hammon). And when we say Krónion, we could also have said Eritía, Eforo, Filístides, Afrodisias (due possibly to the existence of a temple to Afrodita), Timeo, Sileno, and even Isla de Juno – all names given (maybe) to that small detached island. Some writers have also (incorrectly) identified the island and city as Tartessus. Herodotus (ca. 484-425 BC) placed Gadeira on the ocean, beyond the Pillars of Hercules, and near the island of Erytheia. Scylax (late 6th century to early 5th century BC) talked of two islands, one being the city of Gadeira, and being a day’s journey from the Pillars of Hercules. Eratosthenes (ca. 276-194 BC) mentions Gadeira and the ‘happy island’ of Erytheia being in the land of Tartessus.

This is one of the most credible maps of Gadir. We also know today that Cádiz was made up of a smaller and a larger island separated by what could be called a natural canal. Where this was exactly is unclear, but it probably ended in the modern-day Caleta beach.

It is worthwhile eliminating the myth around Tartessus. Experts now think that Tartessus was the same as Tarshish in the Scriptures, a celebrated Phoenician emporium of iron, tin, lead, and silver. But depending upon different authors Tartessus could mean a large region of southern Spain or a town on the Baetis (Guadalquivir). The first mention of this colony was in the mid-7th century BC, but it is now believed that Hamilcar Barca (ca. 275-228 BC) destroyed it (or alternatively it was destroyed by flooding, or it just became economically insignificant). In any case it disappeared, and later writers went on to confused Tartessus with other pre-existing Phoenician colonies such as Gadir. Possibly as early as the 4th century BC the region (including Cádiz) was ‘known’ by its people who had their own culture and their own Tartessian language. We also know these people were important trading partners of the Phoenicians, but Gadir was not Tartessus.

Today we know that there were more than a dozen Punic-Phoenician shrines along the coast between Algeciras and the mouth of the Guadalquivir, and according to Roman sources they were the only shrines in the entire Iberian peninsula, which highlights the role Gadir played in maritime traffic and trade.

Here we have two sarcophagi in white cut and polished marble. They are more than 2 metres long, and date from around 400-470 BC (Punic period or peoples from Carthage). The male sarcophagus was found 1887 in the Necrópolis de la Punta de la Vaca, an area that was being cleared for an International Maritime Exhibition and later for the construction of a shipyard. The sarcophagus of the ‘Dama de Cádiz‘ was found in 1980 in C/Ruiz de Alda, also in Cádiz.

These two sarcophagi are major finds by any standards, and the first find was responsible for the founding of the local Museum of Cádiz. The technique used is said to be Greek or Hellenised Phoenician. The male figure with neat hair and a beard, is holding a pomegranate in his left hand and a painted crown with flowers in his right hand. Other experts have suggested that the male figure has an Egyptian-looking headdress and curly beard, and is holding a heart not a pomegranate. The female figure has a young face and possible would have had reddish hair. I’ve read that the body in the sarcophagus might well have been male. Experts think that the sarcophagi would have been imported (possible from Sidon in the Lebanon) and used by an important gaditanos family.

Before moving on let us stop for a moment to wonder at what the Phoenicians did in Gadir (Cádiz). Some think that they used the town as a base for exploring the Atlantic, and for visiting far away places such as the British Isles.

We do know that they traded in amber and tin with the Greeks, but we still do not know for certain where they got the amber. Amber was worth its weight in gold (it was considered to have magic, curative, and esoteric properties), and the best supplies were in the Baltic (90% of all amber came from the Samland peninsula), but did the Phoenicians travel such long distances?

Supplies of tin were more abundant, but some have suggested that the Phoenicians might have been able to obtain both tin and amber from the Cassiterides or ‘Tin Isles’ i.e. Great Britain. At the time (around 430 BC) these islands were said to be some way off the northwest Iberian coast. The reality was that Gadir went to great lengths to keep its tin trade a secret. The Greeks only knew that tin came to them by sea from the far West, whereas it actually came from both Galicia and Cornwall. There is even a story that says that one vessel was followed to find the location of the Tin Isles, but the pilot wrecked his ship and was reimbursed for his losses from the public treasury.

Some recent work on amber has shown that (a) amber from the Baltic had already arrived in the Iberian peninsula even in pre-history times, that (b) there were some domestic sources of amber, that (c) some Neolithic examples of amber in Gadir actually came from Sicily, and finally (d) that Baltic amber did exist in the Gadir region and was certainly traded by the Phoenicians.

We should also not forget that while the tin trade with the British Isles was a reality, nevertheless the arrival of the Phoenicians was probably motivated by the fact that Gadir was close to the mineral-rich Huelva district and Guadalquivir valley. We also know that tin from Cornwall was smelted with Spanish copper to make bronze ingots that could then be traded in the eastern Mediterranean.

Concerning silver we are on very safe ground. The Phoenician trade in silver can be traced directly to Gadir, and the rich silver mines at Aznalcóllar (north-west of Sevilla) and the gold and silver mines in the mountains of Huelva (the famous inland region of the Rio Tinto). We are talking about serious mining operation, with the last deposit of silver yielding 30,000 tons in 1887. An analysis of the slag at the Aznalcóllar site indicates that during the Iron Age they extracted more than 6 million tons of silver, and there is an abundance of evidence that the Phoenicians were present there.

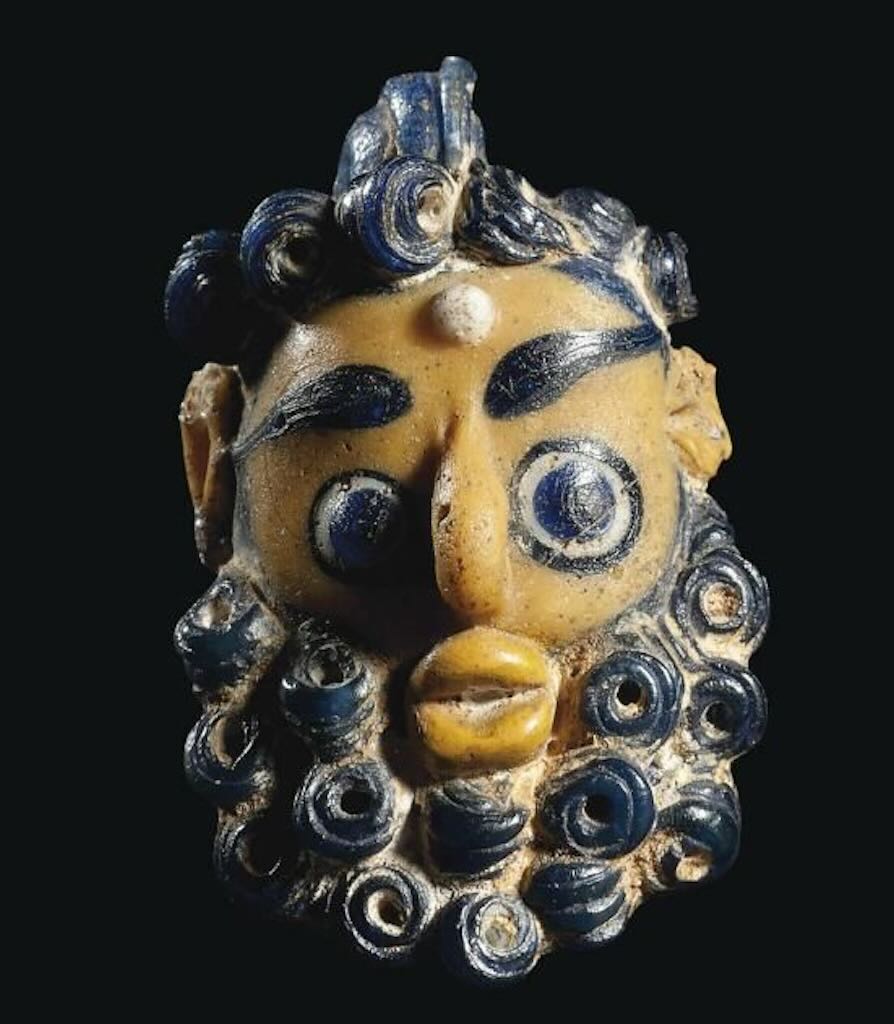

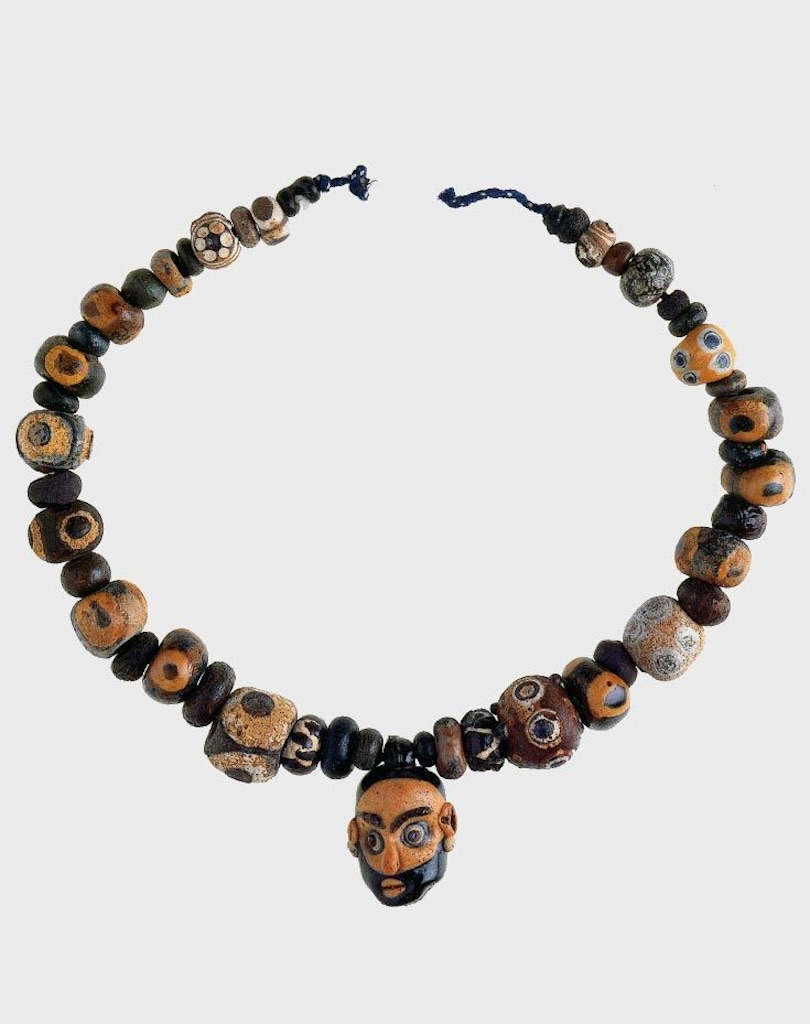

Above we have a Carthaginian glass head pendant (ca. 5th-4th century BC), and below we have a Phoenician glass eye bead necklace (ca. 7th century BC).

Gades was one of the most important Roman cities

Cádiz certainly must have changed hands again after the Battle of Alalia (sometime between 540-535 BC). After which it is said that Carthage became the unquestionable owner of the Western Mediterranean, and Cádiz fell into decline.

The Carthaginian Empire might have known quite well where Gadeira was, but it was during the Punic Wars (264-146 BC) that we find mention of the precise location of the city. We know that the city was conquered by Hamilcar Barca during the First Punic War (264-241 BC), and was used as a depot by Hannibal (ca. 247-181 BC). We also know that the city surrendered to the Roman General Scipio Africanus (236-183 BC) in 206 BC. In fact Gadir was the only city in the region to have resisted the Romans through to the final departure of the Carthaginians from Spain in that same year (Second Pubic War between 218-201 BC, see also the Battle of Ilipa in 206 BC). Some experts have noted that under these circumstances Gadir became the last refuge of the Carthaginians, and they certainly prospered through the thousand and one occasions to trade and barter. Once ‘conquered’ Gades obtained civitas foederata status, which allowed it to maintain its political and economic autonomy, and not pay taxes. Under the Romans Gades flourished as a port and naval base, and Julius Caesar (100-44 BC), during a visit to the city, bestowed Roman citizenship (civitas) on all gaditanos in 49 BC.

The Greek Strabo (64 BC to 24 AD) placed the city at about 70 stadia from the mouth of the Baetis (Guadalquivir), and about 750-800 stadia from Calpe (Gibraltar). The Roman Pomponius Mela, who was born in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and who wrote around 43 AD, said that the island was divided from the mainland of Baetica by a narrow strait of about 1 stadium wide (ca. 185 m), which is now spanned by the Puente Zuazo. The length of the island was estimated at 100 stadia (18.5 km), and width varied between 1 stadium and 3 mille passuum (4.5 km). The city was on the west side of the island and was considered small in comparison with its maritime importance. Even when the Romans had built the ‘New City’ or ‘Double City’, Balbus (early 1st century BC) still said that it did not exceed 20 stadia in circumference and was not densely peopled (because most people were away at sea).

The city derived it wealth from commerce, it was known as the great western emporium of the known world. Firstly we should never forget the Cádiz has always been a fishing port, exploiting fishing banks off the African coast. Often we talk about other exotic commercial practices, but we should never underestimate the continuous presence of the fishing fleets and the associated salazones (salted products). Tuna was said to be fatter in the Atlantic, and it was also said that tides in the bay of Cádiz produced oysters and shellfish of superior size and quantities to that in the open sea. There is good reason to suppose that after the arrival of the Romans Gades continued its commercial and trading practices without interruption. We have to remember that Gades was still a very small island community sitting on Erytheia (see the plan above), and it was in this period that the Caleta canal was bridged to allow an additional area to be built (bringing the city out to the present-day Puertas de Tierra and adding another 4 km to the perimeter of the city). The whole area around the Guadalquivir developed its farming activities, using prisoners-of-war as slaves. And as was the Roman habit, possession of land became a major sign of power and social prestige.

Already the rich dwelt in villas outside the city, either on the mainland or on the smaller island “resorts” such as the Trocadero and Saint Sebastian in what is now called Puerto Real. During a census taken under Augustus (63 BC to 14 AD), we know that the city was home to 500 equites (a wealthy upper class), and thus rivaled Patavium (Padua), and even Rome itself. Gades was also accorded the status of municipium with the title of Augusta Urbs Julia Gaditana, and became one of the four conventus juridici of Baetica. Some authors have rightly pointed out that despite Gades being an important city, it remained a working port. It did not acquire the majestic social architecture of the three great Andalusian Roman settlements: Itálica (outside Sevilla), Baelo Claudia (on the beach of Bolonia), and Acinipo (near Ronda). On the other hand Gades was the end point of the famous Via Augusta (created between 16-13 BC), the principle Roman road crossing all of Hispania, and joined to the Via Domitia. And it did have its theatre, aqueducts (getting rid of the old Phoenician cisterns), necropolis, etc. When the Romans left Gades the aqueducts failed and were not maintained, and the city reverted to the use of cisterns through to the mid-19th century when a mains water pipe was laid.

In addition plenty of Roman coins have been found in Cádiz, even if only one has the epigraph MUN (for Municipium) on the obverse, and Gades with a fish on the reverse. All the others had the insignia of Hercules, and naval symbols, and the names of successive patrons of the city, e.g. Balbus, Augustus, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (64-12 BC), and his sons Gaius Caesar (20 BC to 4 AD) and Lucius Caesar (17 BC to 2 AD), and the emperor Tiberius (42 BC to 37 AD).

We mentioned Balbus, and one of the signs of the importance of the city of Cádiz was the treatment given to its eminent citizens. Balbus actually names two different people, first there was Lucius Cornelius Balbus, the Elder, often called Gaditanus, who went to Rome in 71 BC and became a Roman citizen. He knew well the Roman general Crassus, the statesman Julius Caesar, and Octavian, the first Roman Emperor. He was the first non-Italian native to attain consulship. The second person was Lucius Cornelius Balbus, the Younger, who also became a Roman citizen at the same time as his uncle. He also later became proconsul of Africa, and later still became Pontifex (the high priest of the College of Pontiffs who were the highest ranking priests of the state religion). It was he who built both the New City of Gades and the harbour Portus Gaditanus on the mainland (now Puerto Real), as well as the bridge between them.

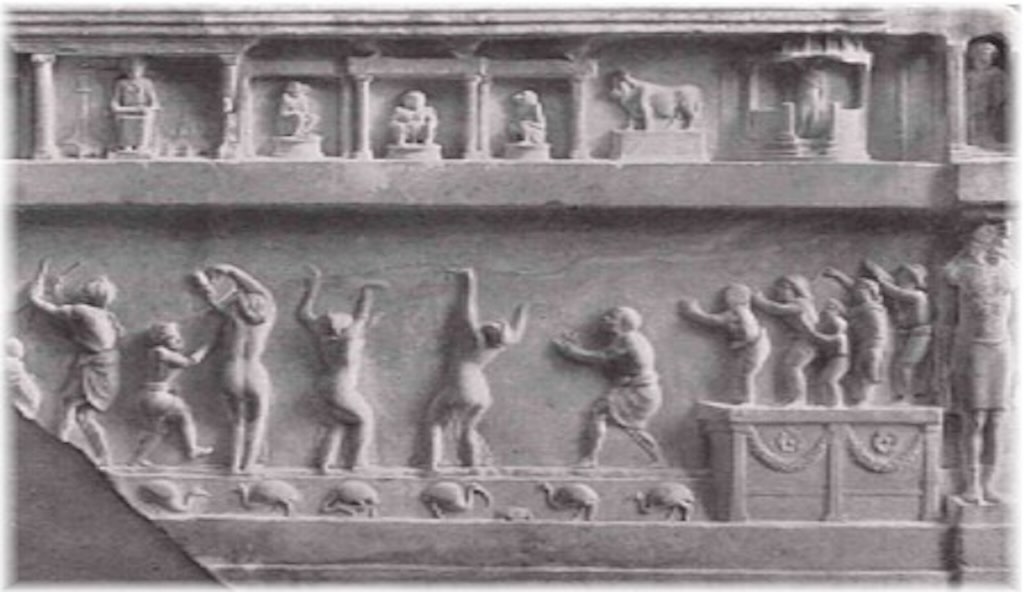

We conclude the Roman period of Cádiz by noting that many authors of the period recorded that the city acquired great wealth, and that lead naturally to luxury, and later to great immorality. For example there is ample evidence that Cádiz was best known in Rome for its cookery and highly erotic dancing-girls.

Below is a 1st century AD Roman relief often used as evidence of the existence of belly dancing (using a very broad definition). Roman authors talk about hip articulation, shimmies, languid arm movements, and the zill-playing (finger cymbals) of female dancers from the old Phoenician and Egyptian cities, and Gades is specifically mentioned.

Below is a small jug made from rock crystal, and dating from the 1st century AD. It was part of a set of rich grave goods made in the same material.

Below is a large Faience urn, dating from the 1st century AD. It is similar to others found in Cadiz.

The Vandals and Visigoths arrived (as did the Byzantines)

As you can imagine the history of Cádiz is typical of a city marked by its strategic military and commercial situation, sitting between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Cádiz was not able to avoid the crisis provoked by the decline of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century AD, and most guide books simply tell us that the city was captured by the Visigoths in 410 AD (the same year they sacked Rome). They also tell us that the Visigoth occupation of the Iberian Peninsula lasted until the arrival of Tariq ibn Ziyad in 711.

In one of the more complex written histories of Cádiz the author subtitles this period as ‘Decadencia y Ruina’.

Was it that simple? The 4th century AD was considered by all as one of peace and relative prosperity. Still today we can find and excavate, in the region around Cádiz, luxury Roman villas that date from this period. But as one author put it nicely, Gades was one of the cities that profited most from the Roman Empire, and thus it was one of the first to suffer. Although the same author also noted that it is impossible to separate the decline of Gades from the urban decadence and decline that hit the entire western Empire. There was a profound demographic crisis in the Roman Empire, that affected maritime traffic, and resulted in the total abandon of Atlantic routes. The result was Gades lost most of its commerce, and thus its source of riches and opulence. Municipal institutions were hit, the quality of water and the cleanliness of the town were affected. The link between the town leaders and the people was broken. The only thing left was the local fishing. And it was also mentioned that almost all maritime commerce became impossible due to both pirates and the poor condition of the port. The New City built by Balbus was in part abandoned, except for an area around the theatro Romano.

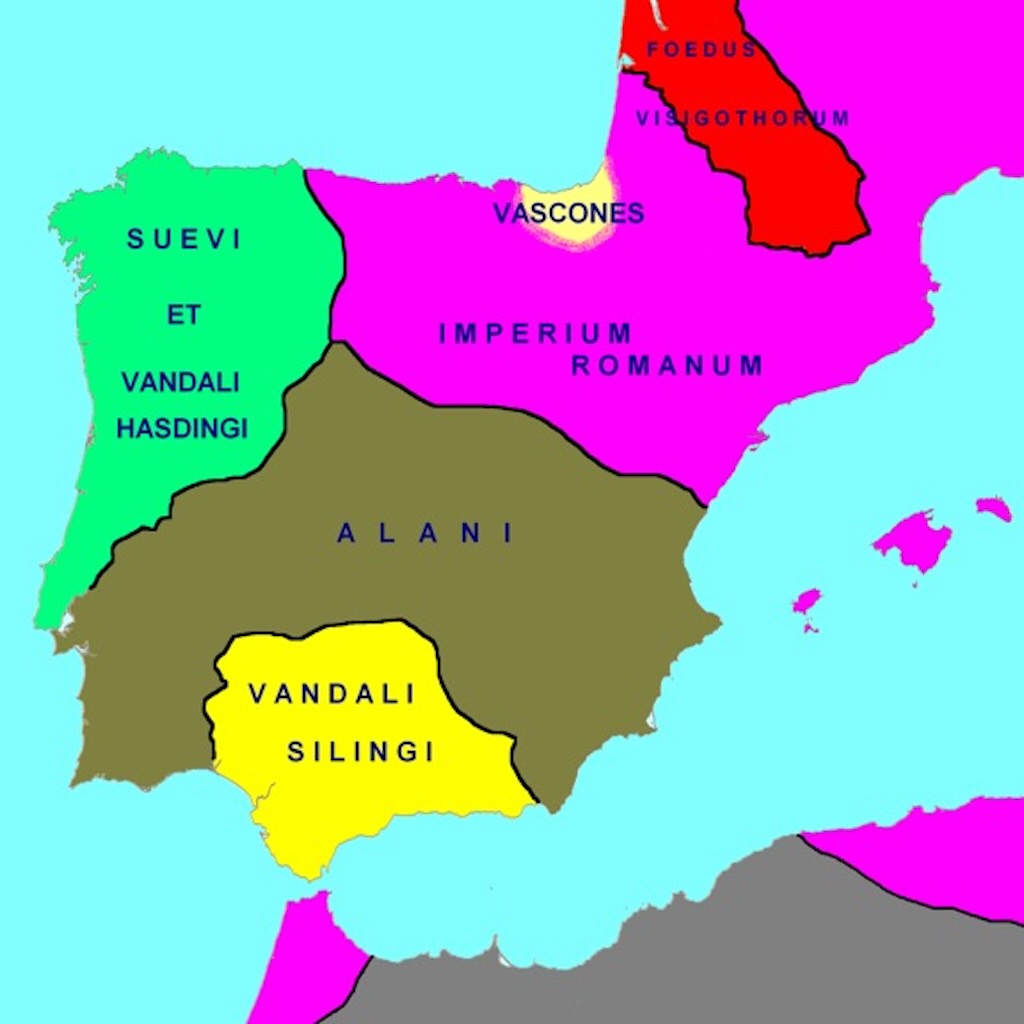

Before the arrival of the Visigoths, we must look first to another East Germanic tribe, the Vandals. They had slowly but surely been pushed west by the Huns, and in 409 they had crossed the Pyrenees and settled in Galicia and Baetica. Baetica, one of the three Imperial Roman provinces in Hispania and approximately corresponding to modern Andalusia, was settled by the Vandal group called the Silingi. But they were constantly attacked by the Roman-sponsored Visigoths (417-418), so they voluntarily subjected themselves to the rule of Gunderic (379-428), King of the Hasding Vandals. In 428 they followed his successor Genseric (ca. 389-477) and relocated in North Africa, and by 439 the Visigoths had taken Carthage (the main granary of the West) and established a kingdom that included Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia and the old Roman African province. In 455 they even sacked Rome, but finally their kingdom collapsed in the Vandalic War (533-534). Genseric has been called the single most disruptive element in western politics until his death in 477. Many of the histories just mention this “relocation” of the Vandals into North Africa, but the reality was somewhat different. In fact Bonifacius, the Roman governor of Africa had rebelled against Rome, and was facing an invasion by imperial troops. He made the mistake to ask Genseric for help. So he cross the straits of Gibraltar with 80,000 people and did not intend to go back. By 439 Geiseric had taken Carthage, made it their capital and settled it.

Below we can see the different settlements in the Iberian peninsula, circa 418, with the Visigoths in red. Their capital was Toulouse.

Below we have the different settlements in the Iberian peninsula, circa 476, and we can see how the Visigoths (in red) expanded into Spain.

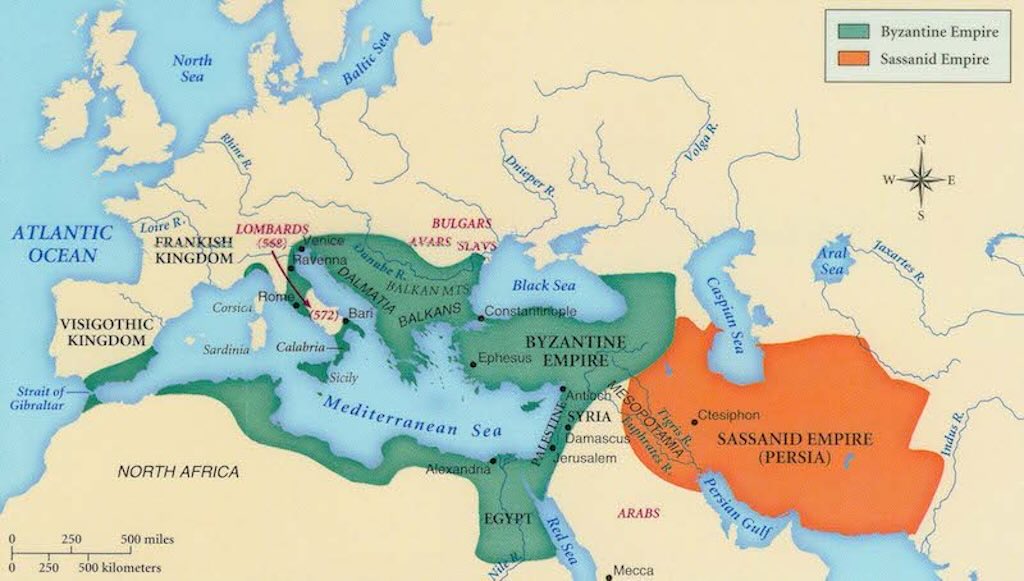

With the Vandals taking Carthage, the Romans sent the Visigoths into Hispania. Ataulf, king of the Visigoths, had already agreed to leave Italy after the sack of Rome in 410, and he had taken as his consort Galia Placidia, the half-sister of the Roman Emperor Honorius. So it was probably not difficult for him to be convinced to attack the Vandali, Alani and Silingi in the Iberian peninsula. By 476 the Visigoths had control over Hispania Baetica, Carthaginiensis (another old Roman province) and southern Lusitania. In conflicts with Franks and the Burgundians the Visigoths later lost their lands in France, and in a conflict with Justinian I, the Byzantine (East Roman) emperor, they saw the Byzantine Empire install itself along the coast of southern Spain (Provincia Spaniae) between 552 to 624 (after they had defeated the Vandals in North Africa in 534).

During this period things would change substantially. We would see the Roman Empire disappear around 476 AD. The Visigoth king Reccared I (559-601) would convert to Catholic Christianity (see the Third Council of Toledo). The Byzantines would be defeated, and their holdings in Spain would be captured, including Malaga. And in 654 a Visigoth book of law, the Liber ludiciorum, would be completed.

We are slowing working towards the Muslim conquest of Spain, but what of Cadiz? During the conquest of the Spanish peninsula by the Visigoths and their conversion to Christianity we hear little or nothing of Cádiz. We know that Cádiz was captured by the Vandals in 426, and we also know that the fires of the lighthouse were no longer maintained. Historians tell us that a few masonry fragments are all that we have of that early city. Clearly Cádiz was captured at sometime by the Visigoths, but it is equally clear that the city entered a significant period of decline. It lost its position as capital of the province, and equally it appears to have lost its commercial and strategic importance. The open style Roman city must have contracted into a ‘typical’ small walled town. We know that in the transition between the Roman Empire and the ‘Middle Ages’ many people had to give up their basic rights in exchange for protection by important landowners. This probably also occurred in Cádiz. However the port must have remained because we also know that it was ceded by the Byzantines to Atanagildo, future king of the Visigoths, in 552, and that they supported him in deposing King Agila in 554. What happened then? Why do we read that the Visigoths ‘retook’ the city in 572? Why do we read that the Visigoths conquered the city in 620? Should we care? In any case we are told that until the Muslim conquest of the region, Cádiz was a backwater known only for fishermen and their salted fish.

In fact we know that the Byzantines preferred to station a garrison and naval force in Ceuta with the responsibility for monitoring events in Spain and Gaul. This was sufficient to control navigation through the straits of Gibraltar and defend southern Spain against a Visigoth attack. Some experts tell us that the Byzantines fortify cities, and built a series of ‘fortified positions’ (castra, castella) linked by roads. Other experts tell us that they simply exploited some existing defensive positions, and did little else.

This sounds reasonable given that there is no archaeologically evidence to support a ‘Byzantine’ era in Spain (and in Cádiz). There are plenty of remains from the 6th and 7th centuries, but nothing to support a Byzantine imperial occupation during that period. And we should not forget that the two key Byzantine-controlled cities were Cartagena and Málaga, so Cádiz was certainly marginalised during that time. There is some evidence to suggest that Medina Sidonia (due to it being on the inland road to Sevilla) might have had some strategic value, but strangely there is little to suggest that Cádiz had the same value.

Some Byzantine coins have been discovered in Cádiz and some Byzantine official weights were found in Algeciras. Both being coastal sites with good harbours would suggest that they were closely connected with Septem (modern Ceuta) with its naval and land forces. And there is some evidence to suggest that guardsmen from Septem were based near Cádiz at the “Pillars de Herakles”. But we should not hide our eyes to the reality. One author concluded that at the end of the 8th century Cádiz had become both insignificant and un villorrio, a dump.

Just to prepare for the Muslim conquest of Spain we are going to mention Mauretania, an area covering Morocco, and the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. A Berber kingdom, they fell first to the Vandals in the 430’s, before becoming part of the Byzantine Empire. There are some indications that the Byzantines ‘attached’ Cádiz to Mauretania, giving it some form of administrative status and calling it Mauritania Gaditana. In any case the Byzantine province was finally lost to the Umayyad Muslim conquest of the Maghreb around 698 (although they regained their independence in the Berber Revolt of 743).

The Arab Conquest

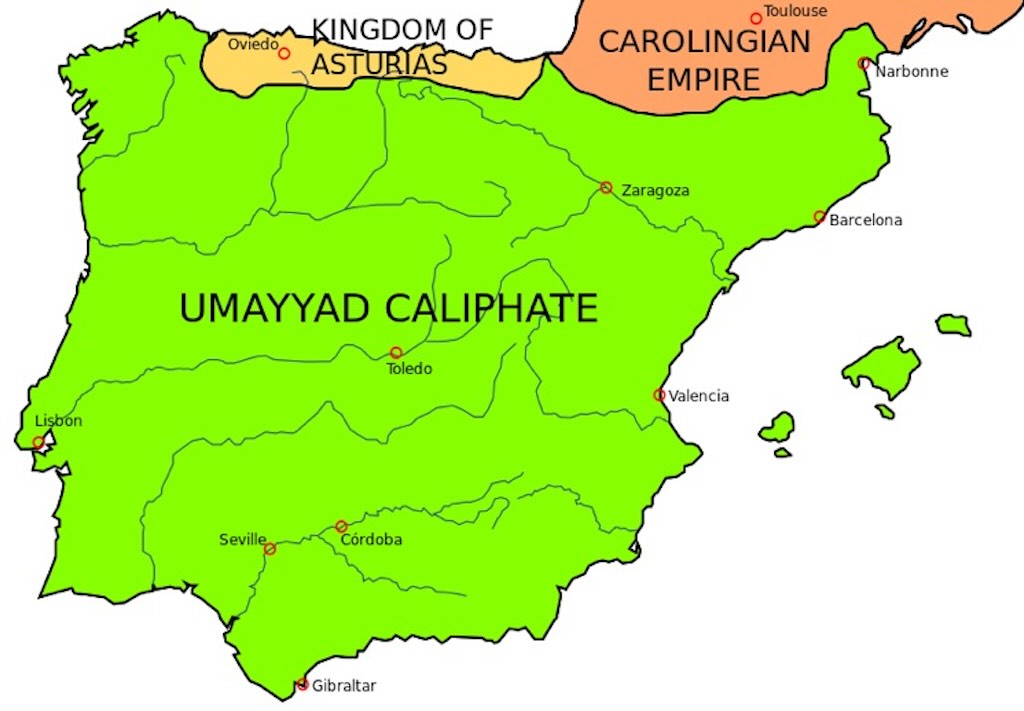

This is not a history lesson, but an attempt to follow the evolution of the city of Cádiz from its creation through to modern day. The first map above shows the gradual expansion of the Muslim Empire (Caliphate) between 622-750, and the second map shows the Iberian peninsula in the year 1037.

The Berbers had raided the southern coast of Spain for sometime, but in 711 they crossed Gaditanum fretum (straits of Cádiz) with a large force. A different source said that an exploratory force embarked at Tarifa in July 710 and headed towards Algeciras to prepare the invasion. The central figure was a Muslim Berber, Tariq ibn Ziyad, under the orders of the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I. We know very little about this period, neither the actors in the drama, nor the exact dates and places of events.

The beginning of the conquest is often associated with the Battle of Guadalete (July 711) between the Christian Visigoths and the Muslim Arabs and Berbers. We do not know where this battle took place, but some people call it the Battle of Jerez de la Frontera. However other experts place it on the Guadalete river (sometimes called Rio de los Muertos), which runs into the Bahía de Cádiz at El Puerto de Santa Maria, just south of the city of Cádiz.

The reality is that little is really known about what happened, and even the year of the invasion is uncertain, e.g. 711, 712 or even 714. Many experts place the Battle of Guadalete somewhere near Medina Sidonia, others tell us that the battle was between 100,000 Visigoth troops against 187,000 Muslim troops (despite mentioning that only 7,000 troops landed!), and others tell us that Roderic lost because of the deceit of Sisebut. In any case the Muslims took most of southern Spain with little resistance. But inland and in the north Visigoth resistance continued, and it would be another 14 years before the Arabs had truly secured the victory of 711.

Once the first battle was won, Cádiz was just a short march away. It was renamed Yazirat Qādis, isle of Qādis, and it would again emerge as an important trading port for both the Almoravid (11th C) and Almohad (12th C) dynasties. We are not talking about a Córdoba, Sevilla, or Granada, but Qādis did get its mosque with a minaret (even if it was a converted Roman building). They even rebuilt the old Roman theatre. Qādis became a small, but vital, market city-port. Some experts have suggested that Qādis could have become, in one way or another, the first Muslim stronghold. Some even have suggested that Qādis actually helped with the disembarkation.

In any case things did not change too much. Qādis remained a fishing port, and its principle activity was preparing and exporting salt and salted fish. Until the late 9th century Qādis was included in the region Saduna with Medina Sidonia as the ‘capital’ (at least until 844 when Medina Sidonia was destroyed by the Normans). From 1034 Qādis was included in Taifa de Arcos, and in 1069 it was included in the Taifa de Sevilla. Some experts suggest that Qādis fell into decay, other suggest that things progressed slowly but surely. What is sure is that the region continued to be known for its salted fish, but it also exported from it orchards, and the region of Jerez became known for its cereal, grapes and olives.

They say that Qādis lived well, but was not able to develop new avenues of prosperity. For example in the mid-9th century Qādis paid an annual tax of 50,600 dinares, as compared to 120,000 dinares for Córdoba, 110,000 dinares for Ilbira (Granada), but more than the 35,000 dinares for Sevilla, and much more than the 19,000 dinares of Algeciras. However it is also true to say that Qādis was excluded from the major commercial networks of the period. Reports also say that Qādis was again captured by Abd al-Mu’min, first Almohad Caliph, in 1147, and came under the direct administration of the Almohad Empire.

One reviewer of the period simply jumped forward several hundred years claiming that Cádiz would only awake again when the 15th century Portuguese explorer Gil Eanes rounded the Cape Bojador (a headland on the northern coast of Western Sahara) in 1434. Other experts are a little more positive about the evolution of Qādis under Muslim rule. We have already mentioned that a mosque was built, and the Roman theatre was rebuilt. They also substantially reinforced the defensive walls of the city. Because of its limited size Qādis was compared with ports of Ceuta or Tunis, but it was also recognised that it was a strategically important land, sea and river communications hub, and one that was much desired by the Christians.

Before moving on it is worthwhile looking at the relationship between Qādis and the so-called Mozarab community in Spain (although the term ‘Mozarab’ was not used at the time). The Mozarabs were Iberian Christians, mostly Roman Catholics of Visigothic rites, who lived under Moorish rule in Al-Andalus. The reality was that Spain evolved as a mix of Muslims, those who had converted to Muslim (Hispano-Muslim), and the remaining Christians. Given that Mozarabs were usually urban dwellers, slaves, labourers, artisans, shopkeepers, etc. we can easily imaging that in Cádiz many people continued to be Christians throughout the Arab occupation.

Equally we know that the agricultural areas around Cádiz must have benefited from the introduction of cisterns, piping, and underground canals for improved irrigation. New areas could be cultivated, new crops introduced, and the productivity of the land was improved. We also know that Islamic law at the time had less restrictions upon the transfer of land, making it easier to bring uncultivated fields back under cultivation (land left uncultivated could be confiscated and resold). Land used for fruit and vegetables was lightly taxed, even if the Mozarabic peasantry paid more taxes. The Arabs also are known to have introduced the pomegranate, the date palm, better varieties of fig, lemons, lime, and sour orange, into the rich Guadalquivir valley. So lots of suggestive ideas, but the reality is that I can not find any major references to this period. We can only conclude that Qādis survived more or less well, and waited for better times to return. And return they would!