Or is it a Betel Box?

I have a small brass container, with some Chinese-like characters on the snug-fitting lid. It is a small, oval box about 6.5 cm long, 4.5 cm wide, and about 2.5 cm deep. The lid is convex, and the base is slightly concave. There are Chinese-like markings on the lid, and a large scratch mark on the base, and the same mark inside the lid.

My questions are obvious. What is it? What age might it have? What is written on the lid?

I gave this challenge to my friendly ChatGPT, and I have tried to collate the answers below. It’s difficult to validate the answer, so any help is welcome.

However, this blog post is as much about asking ChatGPT the right questions and about validating answers, as it is about my small oval brass box. We will see that as we ask more in-depth and more contextualised questions, the answers can change dramatically.

What is the little box?

What can we say about the form, material, and inscription style?

The golden tone and slight oxidation strongly suggest brass (copper-zinc alloy). Brass was widely used in the late Qing dynasty (19th century) through the early Republic era (early 20th century) for durable decorative items.

The initial view was that small oval boxes with snug-fitting lids, were typical for:

-

-

鼻煙壺 (bí yān hú) — snuff, or

-

印泥盒 (yìn ní hé) — seal paste, used to store the red ink paste for personal seals.

-

Given the inscription, the more likely use was for seal paste. We will see later this was incorrect.

But first let us follow our logic for a red seal paste box.

Given the high cultural and literary tone of the inscription (friendship, blessings, dedication), a seal paste box was more likely, rather than a snuff container. Snuffboxes often bore decorative scenes or foreign motifs, whereas (in our case) seal paste boxes frequently featured poetic inscriptions, blessings, or dedications.

We will first look at what was implied with this attribution (even if later considered false).

Red seal paste (印泥, yìnní) is one of the most iconic tools in the Chinese culture of the “scholar-official class”. Its story stretches back nearly 2,000 years. Chinese seals (chops) consist of deeply incised characters carved into stone, ivory, or metal. Ordinary black ink (like that used for calligraphy) was too thin and watery, so it would run and blur. But a paste is thick, sticky, and dense, allowing the carved characters to make a crisp, sharp impression. The paste clings to the raised areas of the seal face evenly, and when the seal is pressed to paper or silk, the result is precise and uniform, almost like a fine print.

In China a seal was a persons identity and their mark of authority. From at least the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) onward a personal seal 印章 (yìnzhāng) carried the legal force of a handwritten signature or a ruler’s decree. Seals bore the name, title, or office of their owner, carved in reverse characters. They were required for official documents (e.g. tax receipts, land deeds, contracts, etc.), artistic authentication (e.g. validating a painting, poem, or literary work), and for letters and correspondence to prove authorship.

So whoever controlled the seal controlled the identity and authority of that person or office. This is why dynastic histories often record dramatic stories of imperial seals being hidden, stolen, or destroyed during political upheavals.

Whist a box of seal paste could make a nice gift, giving a seal meant handing over power and authority. Given a seal would be accompanied by formal ceremonies and documents, e.g. passing a family business to the next generation, or appointing someone to an official post. It could also be symbolic with a master handing a seal to a disciple in art or calligraphy as a symbol of transmission.

To give someone a personal seal outside these contexts would risk fraud or loss of face.

It interesting in that a seal impression is not just a signature. In many ways it’s more permanent and final. A brush or written signature can vary depending upon mood, speed, or even slight hesitation. Whereas a seal impression is mechanically consistent, like a printed mark, it has a more unchanging, timeless quality. It’s an expression of enduring authority.

But to be that permanent expression of authority the seal must “dry”, i.e. meaning fixed in place, much like ink drying on a document.

The paste consisted of cinnabar (朱砂, zhūshā) or powdered mercuric sulphide. A pigment giving a brilliant red colour. It would be mixed with a binder and moisture-retaining natural oil (castor, sesame, or tung oil). In the seal paste box it would be set on a fibrous material (silk, mugwort, cotton).

The little seal paste box would need to have a tightly fitting lid to ensure that the paste had a texture like firm dense butter, e.g. thick enough to sit on the raised characters of a seal without dripping.

Once applied the cinnabar itself never evaporates, however the oil component does slowly dry. Initially the paste sits bright, wet, slightly raised on the paper or silk. It is highly vulnerable to smudging. After some hours the oil begins to absorb into the fibres, the colour darkens slightly, but it still remain delicate. After between one and three days the impression becomes flat, bonded to the paper or silk, and impossible to alter without visible damage. In humid southern China, drying could take three or more days. Whereas in arid northern climates, overnight drying might be enough.

Until the seal dried fully a dishonest party could smudge, lift, or even replace the seal impression. Also the contract or decree could be challenged as invalid, because the mark was still unstable.

Thus, in serious agreements, both sides remained present, or at least their trusted representatives, until the seal’s appearance was clearly stable.

Documents were often left undisturbed under weight (like flat stones or wooden boards) to protect the wet seal. Officials kept them under watch, similar to how wet wax seals on letters were protected in Europe.

Imperial edicts were stamped in the palace, then carried in protective cases. Messengers guarded them day and night until delivery, ensuring no tampering before they dried. With land deeds or contracts both parties might stay together for a sealing ceremony, then reconvene after several days to confirm the mark was intact. Witnesses signed off only once the seal was dry, making fraud easier to detect.

There is a nice expression “The emperor’s decree is not yet settled — it breathes while wet, it commands when dry”.

The Exact Question is as Important as the Answer

Using Chat GPT, or any AI tool, the question is as important, if not more important, than the answer. My question was about the inscription, about the material of the small oval box (I thought brass), and if possible, about its use. The initial focus was on providing a good enough image to allow ChatGPT to understand and translate the text on the lid.

The first step was to note that the text on the lid resembled archaic or stylised Chinese characters, possibly a seal script (篆書, zhuànshū), which explained why it looked less familiar than modern Chinese characters 字 (zì). Obviously the archaic script had been replaced by:-

-

Clerical script (隶书, lìshū) in the Han dynasty,

-

Regular script (楷书, kǎishū) and running/cursive scripts later.

I had situated the small container in the period 1880-1915 for family reasons, so the next question was why would someone chose to use that archaic seal script.

Seal script carries a sense of antiquity, permanence, and authority. And for example, using it on a red seal paste box (an object linked to seals and identity) creates a deliberate echo of the Qin unification, when seals were the literal embodiment of imperial power. Seal script was prized by scholars and officials in the Qing dynasty (through to 1912) as part of an epigraphic revival movement.

Cropping the image allowed ChatGPT to initially identify some common auspicious forms in the text, such as 壽 (longevity), 福 (fortune), and 喜 (happiness).

ChatGPT also identified the script as small seal script (小篆 xiǎozhuàn), which was standardised during the Qin dynasty (3rd century BC). This is the form most often used in decorative inscriptions on boxes, charms, and seals. There exists a large seal script (大篆 dàzhuàn), which is a looser, older family of scripts, rarely used on late Qing/Vietnamese brassware.

Seal script was considered auspicious and elegant, carrying associations with antiquity, tradition, and good fortune. And for the period (late 19th–early 20th century), small seal script was the decorative standard.

Next came a first attempt to understand the overall inscription, which appeared to read as a dedication gift, combining:-

-

A classical friendship phrase (高山流水)

-

A blessing for health and longevity

-

And a named dedication indicating giver and recipient.

This type of dedication fitted perfectly with late Qing (1889-1912) or Republic-era (1912-1949) etiquette, where such engraved boxes were exchanged between scholars or officials.

The Full Message and Meaning

The third column contained another idiomatic phrase, and 白 (bái), which might have been part of a name.

In the final column there was a character strongly resembles 君 (jūn), meaning gentleman/noble person.

I will pass over the next phase, which was to isolate the four individual columns, and isolate each character, then enhance the contrast on each. Then ChatGPT compared each character with classical seal-script references, and attempted a precise but simplified modern Chinese transcription.

Column-by-Column Transcription

Column 1 (Rightmost)

-

Characters visible: 福 壽 康 寧

-

Modern Chinese:

-

福 (fú) = Fortune, blessing

-

壽 (shòu) = Longevity

-

康 (kāng) = Health, well-being

-

寧 (níng) = Peace, tranquility

-

Translation: “Fortune, longevity, health, and peace“

This is a classical blessing, very common on scholar-official gifts.

Column 2

-

Characters visible: 高 山 流 水

-

Modern Chinese:

-

高 (gāo) = High, tall

-

山 (shān) = Mountain

-

流 (liú) = Flow, stream

-

水 (shuǐ) = Water

-

Translation: “High mountains and flowing waters“

An idiom from a famous friendship legend, symbolising deep harmony and mutual understanding.

Column 3

This is where the personal name likely appears.

-

The bottom character is 白 (Bái) which is a common surname in China.

-

The character above it seems like 某 (mǒu) or possibly a stylised given name.

-

This suggests something like: 白某, meaning “Bai [personal name]”.

At this point, the most probable interpretation is the signature of the giver: “Presented by Bai [name]“

Column 4 (Leftmost)

-

The final character at the bottom is 君 (jūn) meaning gentleman, respected person.

-

This column likely forms a dedication line such as: 敬贈君 (jìng zèng jūn) or “Respectfully presented to the gentleman“

The final step was to find the giver’s full name. Its structure suggests a complex seal-script form, which ChatGPT compared with Qing-era seal-script dictionaries. The most likely of three strong possibilities was 益 (Yì). So the full name was 白益 (Bái Yì), with 白 (Bái) a common surname, meaning “white” or “pure”, and 益 (Yì) meaning “benefit, increase, prosperity”.

So the final translation is:-

福壽康寧 — “Fortune, longevity, health, and peace”

高山流水 — “High mountains and flowing waters” (deep, noble friendship)

白益 — “Bai Yi” (the giver’s name)

敬贈君 — “Respectfully presented to the honorable gentleman”

And the full reading would be:

Fortune, longevity, health, and peace.

Like the harmony of high mountains and flowing waters

Respectfully presented by Bai Yi

To the honourable gentleman

Translation is Not Enough

It was perhaps too simple to presume that a small brass box with an inscription in seal script was a seal paste box.

Credibility is good, verification is better. Assumptions and presumptions need to be tested.

Small brass boxes with seal scripts and a blessing style were typical of this transition period. They were know to be gifts that were exchanged between educated men, and such boxes were used during official duties requiring a seal.

However:-

Chinese seal paste boxes were typically small, but the vast majority were round. Common diameters 3–6 cm, with a depth 1.5–2.5 cm. Oval forms were very unusual for seal paste.

Chinese seal paste boxes were usually made of porcelain, and lacquer and cloisonné boxes were also frequent. Brass seal paste boxes did exist, but were a minority, and usually round.

The insides of Chinese seal paste boxes were often stained red-orange (cinnabar), smooth, slightly oily. They rarely showed pitting or verdigris, and since they were not used with tools, and there would be no gouges inside the lid.

But it was very common for Chinese seal paste boxes to have lids with Chinese characters (often in seal script).

However it’s important to push deeper. The reality is that Chinese seal paste box were usually made of porcelain, lacquer, or cloisonné, and those made in brass were usually better finished, with smoother, finer-grained alloys, sometimes with gilding or cloisonné. Normally, a little brass box would have been worked to look elegant and not just “functional” or “utilitarian”.

Turning to Betel in Vietnam

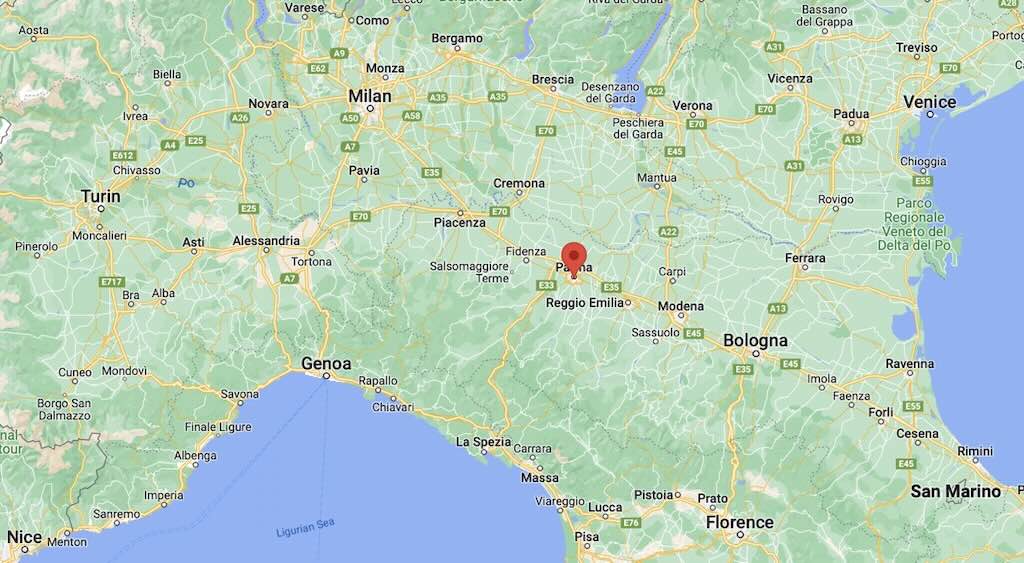

This small brass box came from my wife’s French parents, who were both born in Vietnam, and who spent most of their lives in Vietnam before returning to France in 1949.

I have increasingly noticed that it is important to differentiate between China and Vietnam, and between the different provinces of French Indochina, namely between Cochinchina, Tonkin and Annam. I was blindsided by the idea that “seal script” appeared so obviously linked to my “oval seal paste box”, that initially I did not look beyond.

So now I asked my friendly ChatGPT about the use of such small oval brass seal paste boxes in Vietnam. I was just checking that what I had learned was as valid in Vietnam as in China.

But “lo and behold“, a new, and totally unknown element to me, was introduced.

This was Betel, which is a species of flowering plant in the pepper family Piperaceae, native to Southeast Asia. It is cultivated for their leaves which are most commonly used as flavouring for chewing the Areca nut.

Betel is a mild stimulant chew, widely used across South and Southeast Asia for centuries. It is still chewed in some Asian countries but in Vietnam today it survives mainly among elderly rural women and in symbolic form at weddings and ceremonies.

It’s not a single plant, but a combination usually called betel quid or paan. The main element is the leaf of the betel vine (Piper betle, a climbing pepper family plant). The leaf is smeared with slaked lime (calcium hydroxide), and a piece of Areca nut (often called the “betel nut,” though it actually comes from the Areca palm, Areca catechu) is placed inside. Other ingredients may be added such as spices (cardamom, cloves), catechu resin, and sometimes tobacco. The mixture is folded into the leaf and chewed.

It’s a mild stimulant (due to alkaloids in the Areca nut, primarily arecoline). It produces a feeling of alertness, warmth, and slight euphoria. Chewing releases red juices, and users habitual spit or swallow this, which stains teeth and lips deep red. Habitual chewing can lead to oral cancer, gum disease, and tooth decay. Modern health campaigns in many countries now discourage it, though the tradition persists in parts of Asia and the Pacific.

In Vietnam betel chewing was central to hospitality, and small brass, silver, or lacquer boxes were made to hold leaves, Areca nut slices, and lime. This explains the importance of oval or rectangular betel boxes.

In China this practice was/is far less important, though it was found in southern provinces (Guangdong, Hainan, Taiwan).

So Is Our Little Brass Box Really for Betel?

Yes, almost certainly.

In 19th–early 20th century Vietnam, betel chewing was universal across classes, and the boxes (whether brass, silver, or lacquer) were often decorated. Since Vietnam still used classical Chinese (Hán) as the prestige script, inscriptions on household and ritual objects frequently appeared in Chinese characters.

For betel boxes specifically, brass and silver examples are known with inscriptions in seal script (篆書). The characters were almost always auspicious ones with 壽 (longevity), 福 (fortune), and 喜 (happiness). Seal script was chosen because it looked antique, auspicious, and elegant, and it wasn’t expected that everyone could read it fluently.

Oval brass betel boxes were common in northern Vietnam (Hanoi, Nam Định, Bắc Ninh). Brass was the everyday material, being practical, durable, and modestly respectable. A 6–7 cm oval brass box with auspicious characters on the lid is exactly in line with Hanoi betel culture of that period.

Such boxes were not rare in Vietnam. The use of Chinese-style seal script on a Vietnamese betel box was completely normal.

More specifically the turned-in lip and the alkaline pitting/verdigris in this box are textbook signs of lime/Areca use (not seal paste).

Brass was the everyday working material for betel in Vietnam. Vietnamese workshops in Hanoi routinely used Hán (classical Chinese) characters, often in seal script (篆書, xiǎozhuàn), for auspicious lids (壽 longevity, 福 fortune, 囍 double happiness). That this lid uses a stylised, hard-to-read archaic form is normal for a Vietnamese betel box and doesn’t imply Chinese manufacture.

Not visible in the above photo, there are three sharp indentations on the inside of the lid. Betel chewing required repeated handling of lime paste (very alkaline, and often semi-hard). Users carried small spatulas, sticks, or metal picks to scoop lime or nut fragments from the box. They sometimes pressed or tapped the spatula/tool against the inside of the lid (to scrape off excess or to close the box tightly while a tool was inside). Over time this produced small sharp dents or puncture-like marks in the lid interior. Museum betel boxes often show scratches, dents, or small gouges inside, especially near rims or lids. So these marks are coherent with lime/nut use, but not with seal paste.

Taken together this small brass oval box is almost certainly a Vietnamese betel box, and not, as originally imagined a Chinese seal paste box.