I admire the idea of books, what they are, and what they represent, both intellectually and personally.

Books are the carriers of civilisation. Without them, history would vanish, science would be crippled, and human thought would be ignored…

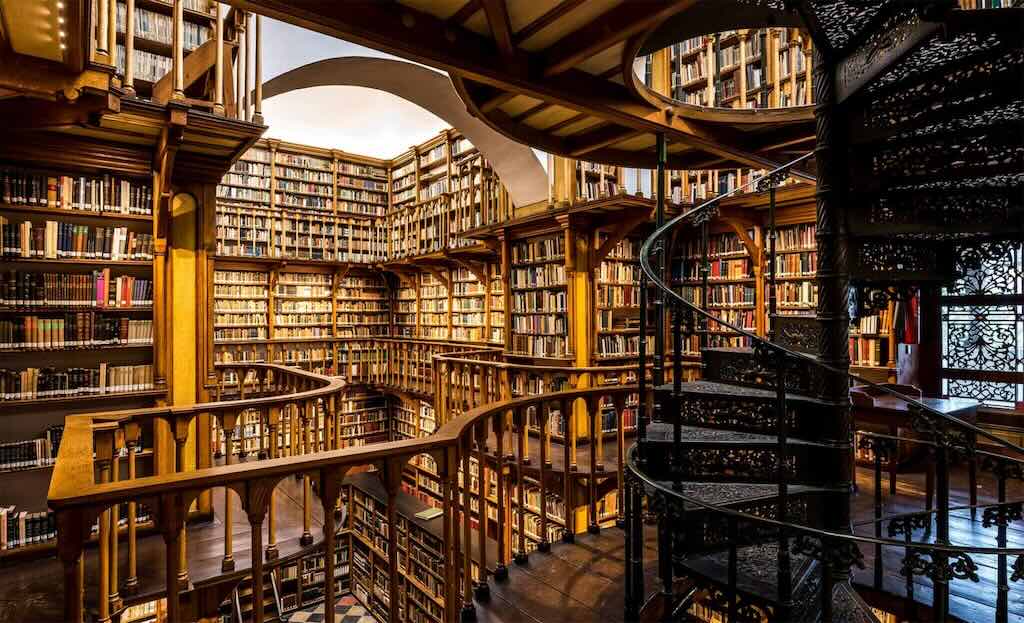

A wall of books records human effort, and my own passage through life. But admiration alone doesn’t give them the right to occupy space in my home. Shelves are finite. Time is finite. My attention is finite. I brought these books into my life, but the question now is which still belong?

The real challenge is to decide which books still deserve space on my shelves, in my life, and in my future?

How to Assess a Book?

When I hold a book, I must ask myself:-

- Is it a tool I actually use — for reference, knowledge, or consultation?

- Is it part of my identity — does it speak of who I am, or who I refuse to forget I once was?

- Does it inform or challenge me — opens my mind, deepens my knowledge, unsettles my assumptions?

- Does it hold memory — a gift, a stage of life, a treasured moment?

- Does it command my attention — will I read it (again), in the years I still have?

- Does it embody value — is it scarce, out of print, or otherwise irreplaceable?

- Does it bring me pleasure — lightens the day, sparks curiosity?

If the answer is yes, the book stays. If not, then its time with me is over. My shelves are not storage.

But, there is always a but! In the end, I won’t let a rule decide for me. I must judge each book on its own merit. For example, what might look like an obsolete reference book may, on closer inspection, reveal itself as a historical artefact.

Are There Practical Filters?

For example:-

The 10-year test: will I actually read or use it again?

Reacquisition test: if I gave it away, could I easily replace it?

Space-to-Value test: is it worth the physical shelf space?

Legacy test: is it part of my identity?

Frankly, I’m not sure I can apply systematically these types of filters…

The Reference Book

A reference book is a work designed to be consulted for specific information. Most are organised alphabetically (e.g. dictionaries, encyclopaedias, atlases, almanacs, etc.), and used to look up facts, definitions, data, or precise, short explanations. Most are produced by specialists or institutions, intended to be trusted sources, and they can be broad (encyclopaedic) or narrow (domain dictionaries).

I have (or had) lots of reference books, but how frequently do I consult them for specific information? Once they were indispensable, but now online resources are faster, more comprehensive, constantly updated. In seconds I can check ten dictionaries, cross-reference Wikipedia, the OED, or specialised sources. The logical case for keeping a dictionary or encyclopaedia has long gone.

Living in a multilingual, multicultural world, I have reference books in French, Italian, Germany, Spanish, and even some in English. I have sets of old encyclopaedias, and out-of-date books on everything from antiques & collectable prices, to wines and golf courses.

Until recently my reference books sat in pride of place, on shelves just above my computer monitor. They looked great, were a statement of my (presumed) intellect, but when was the last time I used them?

Now moving to a new apartment, and firmly decided to “rightsize”, do I keep them?

How to decide? It’s true that an old atlas still invites browsing and discovery, in a way that a screen can’t (yet). Some thematic dictionaries might contain interpretive richness that raw online data lacks. A trusted edition, especially in specialised fields, could complement the shallowness of search results (increasingly unlikely with AI). Some books remind me of how I once studied and learned, and some are just beautifully made.

Let’s face it, a beautiful leather bound collection of Larousse merits its place, just for its good looks. But does Miller’s Antiques Price Guide from 2007, despite the great photos and useful price history, still merit its place?

Decisions, decisions, one book at a time…

A Real Live Test

Take my Harrap’s French–English Dictionary from 1980. Once indispensable, today it holds no memory, no personal value, no future use. It is not yet history, so it’s just redundant. That book went to the Bicherbox in my local commune, where it may still have found a new owner.

Same for Larousse French–Spanish Dictionary (1989), Larousse Spanish Dictionary (2007), Grand Larousse Italian Dictionary (2006), Langenscheidt French–German/German–French (1987), Duden Großes Universalwörterbuch (1996), and Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (1998).

In 1966 Britannica published a two-volume World Language Dictionary. As a tool it is long redundant, outpaced by digital sources in every direction. Yet it remains on my shelf. My wife and I once owned the full Encyclopaedia Britannica and its yearbooks, but they were already “moved on” in 2008. However, I’ve kept the two-volume dictionary. It survives not for its utility but as a fragment of that vanished library, a reminder of my own choices as much as of Britannica’s authority.

On the other hand, I also felt a certain sympathy for my New Oxford English Reference Dictionary of 1996. It had presence, authority, even a kind of dignity. But every fact it held was already available online, more complete and more current. Sympathy alone cannot justify its space, so this book also went to the Bicherbox.

Not every dictionary was doomed to go. My two-volume Oxford Shorter English Dictionary on Historical Principles, 1980 edition, survived. I bought it when I first joined the European Commission. Outdated as a quick tool, perhaps, but for me it is neither tool nor ornament. I kept it because it marked a beginning, an identity, a memory.

In fact, not all dictionaries are equal. My Palazzi Italian Dictionary from 1973, for instance, will never again serve as a practical tool. But I moved to Italy in 1974, and that book marks the threshold of that change. It belongs on my shelf not for its definitions but for what it represents, my first step into another language, another culture, another life.

Some books stay not for their content, but for their inscriptions and connections. My copy of Le Quillet Flammarion from 1963 carries a dedication to my wife from Pierre Gioan, her grandmother’s sister’s husband, and one of the principal authors of the work itself. Outdated as a reference, it remains priceless as artefact binding family, memory, and authorship in one volume.

My Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, 1989 edition, was formally given to me by the European Commission in 1992 when I changed services. As a dictionary it has been long eclipsed, but as an artefact it is untouchable. It represents a moment in my professional life, a trace of official recognition (albeit very limited), and a connection to the Europe I once worked for, and still believe in.

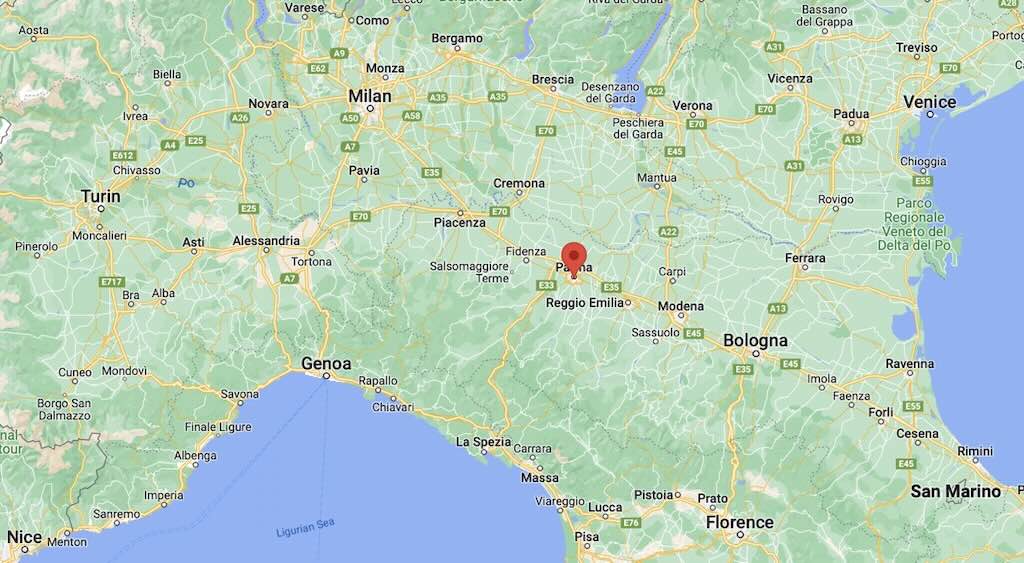

Pierre Larousse was a provincial schoolteacher from Toucy (Yonne) who believed that education and access to knowledge were the foundation of a free, rational society. After teaching for several years, he moved to Paris in the 1840s and began publishing educational manuals for the new secular schools created under the July Monarchy (1839-1848).

In 1852 he and Augustin Boyer founded the Librairie Larousse et Boyer, a small bookshop specialising in grammar books, pedagogical works, and affordable dictionaries. Their motto, later famous, came from Larousse himself:

Je sème à tout vent (I sow to every wind)

It symbolised his aim to scatter knowledge widely and freely.

Larousse’s great dream was to create a universal dictionary of language and knowledge. The result was the monumental Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle (15 vols + 2 supplements, 1866–1876).

It mixed rigorous scholarship with ideological zeal. It was republican, secular, anticlerical, and committed to progress through education.

The work was a cultural event, falling somewhere between an encyclopaedia and a manifesto of the French Third Republic’s (1870-1940) values.

Larousse died in 1875 before the last volumes appeared, but the Grand Dictionnaire established the house as France’s leading reference publisher.

After Pierre’s death, his heirs and associates, led by Claude Augé (1854–1924), a school inspector from L’Isle-Jourdain, reorganised the firm as Librairie Larousse.

Augé modernised both the pedagogy and the publishing aesthetics, with cleaner typography, abundant illustrations, and a strong Art Nouveau visual identity (with artists such as Eugène Grasset, designer of the famous Semeuse girl blowing seeds).

The Nouveau Larousse Illustré (1897–1904, supplement 1907) was his answer to the old Grand Dictionnaire. It was more compact, richly illustrated, and adapted to the general educated reader rather than scholars. It became a fixture of middle-class parlours and schools, both a status symbol and a domestic tool of knowledge.

When I met my future wife, Monique, she did not have very many books, but there was in her study (second bedroom), a copy of the Nouveau Larousse Illustré, with supplement. Because of its specific characteristics, i.e. the printing on the spine, the binding, the mention of Claude Augé etc., and the inclusion of the death of Zola, its possible to date Monique’s edition to 1903–1904. In addition, the supplement of 1907 was sold (as indicated in pencil) for 45 Francs net.

To finish, the Nouveau Larousse Illustré was one of the great subscription-based publishing ventures of the Belle Époque. Each of our volumes were signed by a certain Henri Wily (or similar) who was most likely the bookseller or agent. The price 45 Francs (equivalent today to ≈ €180–225) was accessible to the educated middle class but out of reach for the working class.

This set has historical and aesthetic value more than high monetary value. Today it’s probably worth about €150-200 for the 8 volumes.

The publisher was Amalgamated Press, London, founded by Alfred Charles William Harmsworth (later Lord Northcliffe, press magnate and founder of the Daily Mail). It was first published 1905–1913 (in parts and volumes), the editor was J.A. Hammerton, and at the time it was one of Britain’s biggest early-20th-century popular encyclopaedias. It was the English counterpart, in spirit, to the French Nouveau Larousse Illustré.

Just like the Larousse, it was sold by subscription, issued first in weekly parts (6 pence each) and then in monthly parts and bound volumes. My edition is in 9 volumes, which means it dates from 1908 – 1911.

I remember buying it in a local sale, just wanting to put it next to Monique’s Larousse. Street value today €70, if there is a buyer out there. Today they sit proudly next to each other, both unused, but both symbolic of a time when the education of the middle classes was important, and man might have hoped to possess an encyclopaedic knowledge of the world.