I had decided to follow an Oxford University Summer School (2026) on the subject “130 Years of Discovery: Nuclear and Particle Physics from Becquerel to Gianotti”.

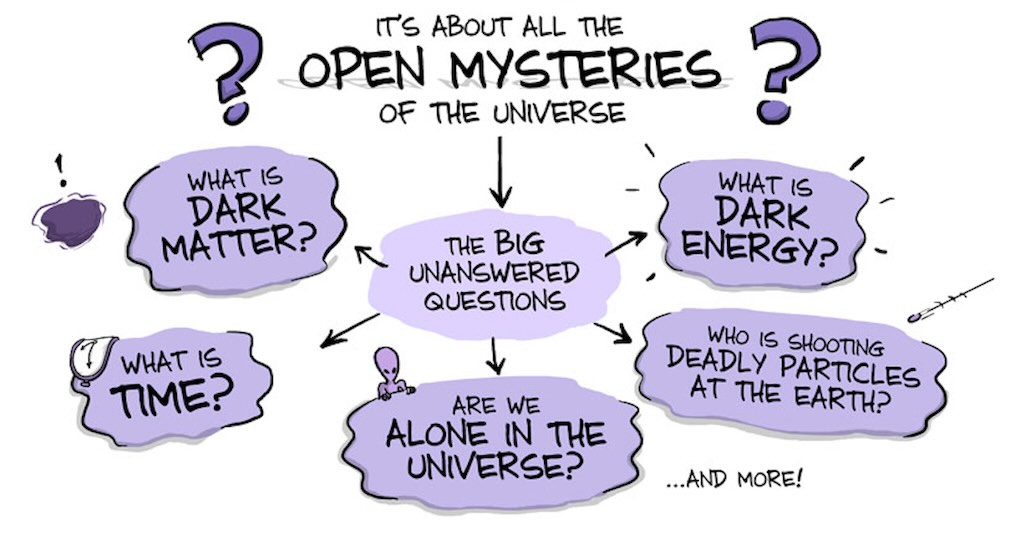

One of the recommended reading was “We Have No Idea” by Jorge Cham and Daniel Whiteson. It is subtitled “A guide to the unknown universe”. Check out the video (maybe you don’t need to read the book). It could have been subtitled “A guide to our staggering cosmic level of ignorance”, but I’m not sure that would have been a good “come and buy me”.

In reviewing this book I decided to try to create a set of bullet points, almost like a revision check list. Since the book is about things scientists don’t know about the universe, I assumed it would be a short set of bullets. Big mistake, it would appear that we know very little about an awful lot of stuff.

I must say I found this book very informative, and easy to read. I would second one reviewer who wrote “accessible, entertaining and very enjoyable”.

What is the Universe Made of?

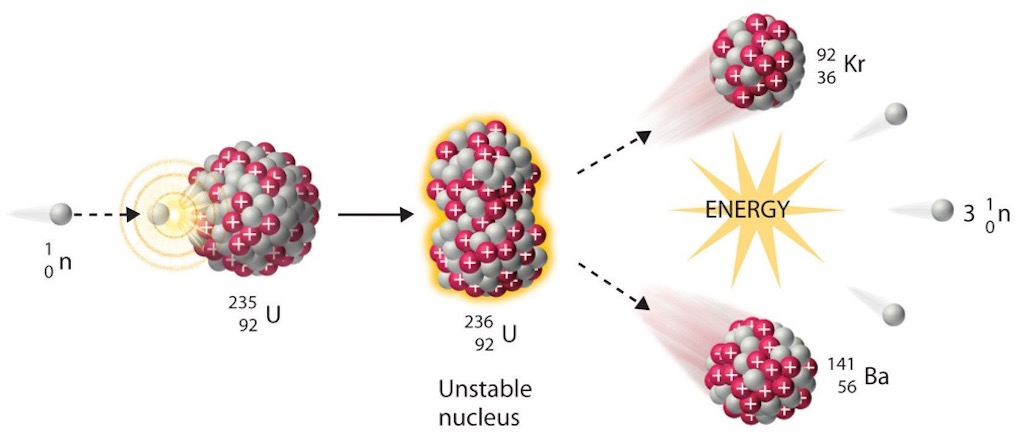

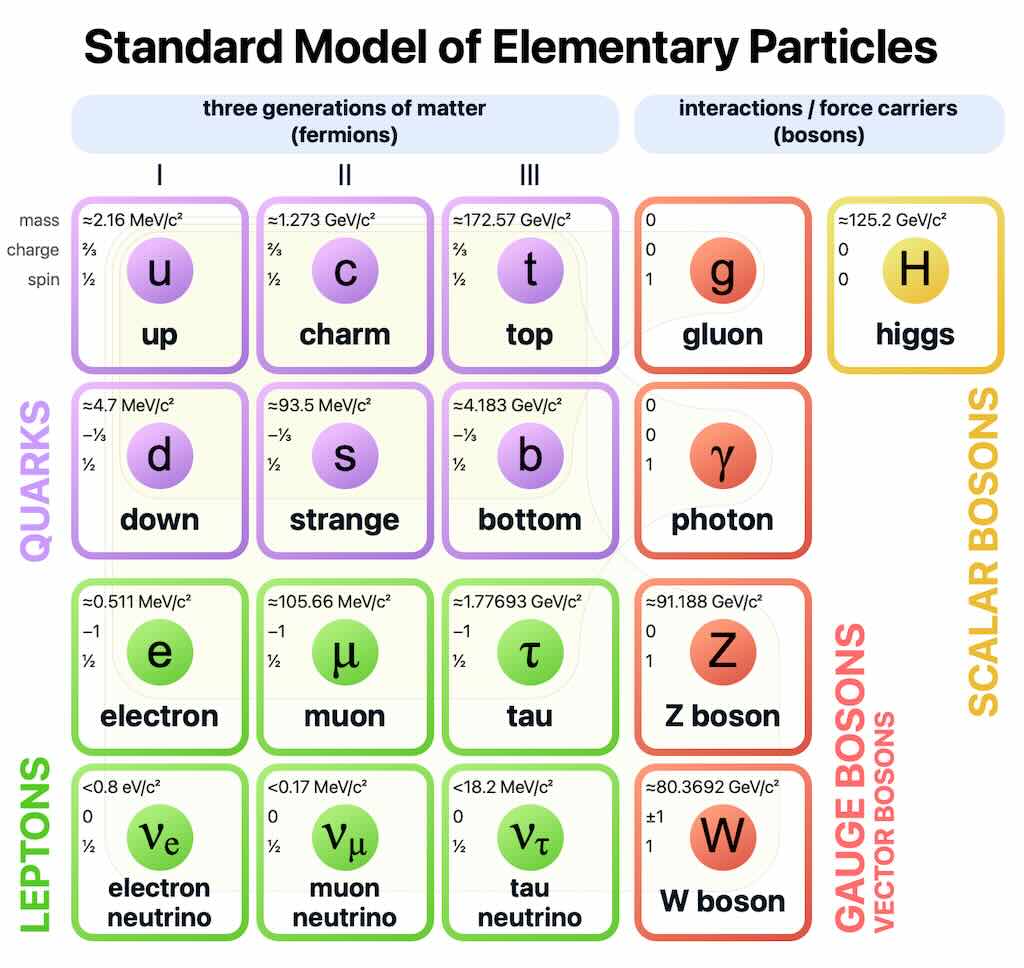

- Matter is made up of the Chemical Elements in the Periodic Table

- The Atomic Nucleus is made up of Protons and Neutrons, and Atoms are just a nucleus surrounded by a cloud of Electrons

- With the Up Quark and Down Quark, and the Electron, we can build all the elements in the Periodic Table (there are other particles, but we only need these three to build all normal matter)

- The Proton consists of 2 up and 1 down quark, and a neutron consists of 1 up and 2 down quarks. Looks simple.

But more importantly normal matter is only 5% of universe, and 27% is Dark Matter, and 68% is Dark Energy. We might begin to know a little about dark matter, but we know nothing about dark energy.

We know that dark matter is needed to explain why galaxies don’t fly apart, and we know that dark matter deviates light (see Gravitational Lensing).

Colliding galaxies showed that dark matter when colliding does NOT actually collide, it just passes through each other.

So dark matter has mass, is invisible, groups together in massive blobs, is found in galaxies, does not interact with normal matter, or other dark matter.

- Dark Matter means it has mass (matter) but is invisible (dark)

- This means that gravity works, but electromagnetic, strong and weak forces don’t

- So dark matter does NOT interact with telescopes, detectors, etc.

Is dark matter a WIMP – weakly interacting massive particle, or a MACHO – massive astrophysical compact halo object? Don’t know!

- The evidence for dark matter is gravitational and overwhelming (galaxy rotation curves and gravitational lensing)

- Dark matter does not interact with light, so it can’t be trapped with mirrors, lasers, or electromagnetic fields

- Dark matter (whatever it is) interacts extremely weakly with ordinary matter

- Every second, vast amounts of dark matter are already passing through everyones body, everyones house, and the entire Earth without it being noticed

- It’s estimated that billions of dark matter particles pass through every square centimetre per second, and they simply keep going.

- Originally scientists thought universe was static

- Then they noticed everything was moving apart, so the universe was expanding

- Logically, since it was smaller before, it must have started as something very small, a Big Bang

- This did not mean a small thing in a big empty space

- Before the Big Bang there was no space

- Given that if there is a lot of mass in the universe, gravity will eventually pull it all back down to a point

- Or if the mass is not enough, the universe will eventually dilute and go cold

- Or if there is just enough mass, it will gradually expand, slow down, and stop.

Check out the video which describes how to look at old stars (far away) and compare their movement with younger (nearer) stars. This uses Doppler Shift and a type Ia supernova as a “standard candle”. The result is that the universe is expanding faster now than in the past. In fact, it did start to slow down, but in the last 5 billion years it has gone faster.

So space is not static, it can bend light, propagate ripples, and expand.

This is not stars, planets, etc. moving into space further away. What is actually happening is that something is creating more space allowing the universe to expand faster and faster into it.

But it takes energy to push and create space, and this is “dark energy”.

Firstly, the measured cosmic microwave background is very sensitive to the amount of mass, dark matter and dark energy. Secondly, it’s possible to calculate the amount of dark energy needed to justify the present rate of expansion of the universe. Thirdly, it’s also possible to model how much dark energy and matter is needed to get from the big bang to today’s universe.

Is dark energy the energy of empty space? No, vacuum energy (the underlying background energy that exists in space throughout the entire universe) is too much.

Is it a new force or field?

If expansion continues to increase then one day the expansion will go faster than the speed of light and the universe will start to go black.

What is the Most Basic Element of Matter?

We know very little about dark matter and dark energy, and there is a lot we don’t know about the 5% of matter that we do see everyday.

We know that quarks make up particles, which make atoms and elements, which make molecules, and they make us.

- The atomic number of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus

- We only need the atomic number to uniquely identify ordinary chemical elements

- Ordinary nuclei are composed of protons and neutrons and in ordinary uncharged atoms, the atomic number also tells us the number of electrons

- We know that the other particles are heavier, some very, very heavy, and have varying amounts of charge

- Some types of quarks feel the strong force, others (like the electron) are leptons that don’t feel the strong force.

Why are the other quarks and leptons heavier and have different charges? What use do all those extra particles have? Why does the proton have the exact same charge as the electron, but with an opposite sign? No one knows!

Ignoring anti-particles, there are five force-carrying particles:-

- Electrons only interact through the weak and electromagnetic forces

- The W+, W−, and Z0 are vector bosons, and are the force carriers of fundamental interactions. These elementary particles mediate the weak interaction

- The Gluon is also a vector boson, and is a type of massless elementary particle that mediates the strong interaction between quarks, acting as the exchange particle for the interaction

- The Higgs Boson is a massive scalar boson that couples to (interacts with) particles whose mass arises from their interactions with the Higgs Field. It has zero spin, even (positive) parity, no electric charge, no colour charge, and is very unstable, decaying into other particles almost immediately upon generation.

Some particles appear useless but are observable (part of the 5%).

Why do quarks have fractional electric charge? But if you make a neutron, the charges add to 0, and if you make a proton, the charge adds to +1. Thats exactly the same as the -1 charge of the electron. If that were not the case, life would not exist. But what does a fractional charge mean? Why does the proton and electron have the same charge (but opposite)? Does this balancing of charge point to other, yet not detected, fundamental particles?

The Mysteries of Mass

We can all feel mass. It’s the energy we need to move something, so it’s called “inertial mass” because inertia is resistance to acceleration (Isaac Newton’s first law of motion).

- We measure mass by applying a known amount of force and measuring the acceleration

- But the mass of something is not the addition of the mass of the elements (particles) making up the object

- It must also include the energy needed to keep the things together

- Break up an object into it elements releases energy, which has mass

- In fact the mass of the three quarks in a proton actually only represents about 1% of its mass, the rest is the binding energy

- We are made up of these atoms, but most of our weight is in the energy needed to keep our atoms together.

Why? Don’t know! Why is inertia linked to mass and energy? Don’t know!

Given that particles are considered points with zero size, we are just empty space.

- An electron has zero size and zero mass. But if an electron has zero size and mass, where does it keep its charge

- Quarks also take up zero space, yet the top quark is 75,000 times heavier than the up quark.

- If a photon is a particle with zero mass, what is it made of?

So mass is just a label, like charge!

Mass is a thing that gives a particle inertia, resistance to motion. But why?

The answer is the Higgs Boson.

- It’s a field that makes it hard to move particles or to slow them down. So it’s like having inertial mass

- The more the field interacts with a particle the more it appears to have inertia

- More inertia does not mean more mass, inertia IS more mass.

In a sense the Higgs Boson is a quantum number and not an amount of stuff. So more or less mass just means they feel the Higgs Field differently. We don’t know why?

Gravitational mass is like a charge in that it acts on both objects/particles, but it is always an attraction.

So technically inertial mass and gravitational mass are different, but in practice they are always the same identical number. This equality is tested extremely precisely, and today the difference is less than one part in 10 trillion.

Why? Don’t know!

Gravity is incredibly weak compared to other forces. For example, a little magnet can lift a nail working against attraction of the whole of the earths’ mass.

But the weak and strong forces only work over small distances, whereas gravity works with very big masses over very large distances. Also gravity can’t be cancelled out. So gravity is odd, it is very, very weak and only attracts.

The Graviton is the hypothetical elementary particle that mediates the force of gravitational interaction. It is a quantum of gravitational wave energy, and is expected to be massless because the gravitational force has a very long range and appears to propagate at the speed of light. But it has not yet been detected.

What is Space?

Outer Space is not empty (it’s full of energy) and it’s not just the gap between matter. Space can be bent by gravity, can expand (remember dark energy) and can ripple, so space is something.

- The idea is not that a planet circles a sun pulled by gravity

- It is because space is distorted to guide the plant in its orbit

- The planet thinks it’s going in a straight line but is actually making elliptical orbits

- But this is general relativity, and not quantum mechanics

- We haven’t yet detected gravitons

- But we have detected gravitational waves with LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory)

- Some argue that the graviton is very weak because it’s spread over many other dimensions.

But is space flat or curved?

If it’s flat, this would mean that things would go in a straight lines forever (but we don’t know if it goes on forever, it might not).

Remember its mass and energy that gives the universe a curvature, and space is in fact flat because it has just the right amount of mass and energy.

It’s five hydrogen atoms per cubic-metre that makes it flat, no more, no less.

Why is space flat? Who knows!

What is Time?

Time is like space, it is another direction we can move through. And both time and space can be chopped up into small pieces. But we can’t move around in time, we can only move at a fixed pace in one direction.

There is causality, where one event, process, state, or subject (i.e. a cause) contributes to the production of another event, process, state, or object (i.e. an effect).

However a lot of the microscopic laws of physics work backwards as well as forwards, but this is not true for macroscopic laws.

For example, Brownian motion is a random walk caused by countless microscopic collisions (e.g. water molecules hitting a pollen grain). That randomness means it can move forward, and it can move backward. It can reverse direction instantly. So Brownian motion has no inertia-dominated momentum, no smooth trajectory, and direction changes constantly because molecular impacts are uncorrelated. So it just wanders, but this doesn’t mean time is running backward.

On the other hand, a tennis ball (macroscopic) has large mass compared to air molecules. So inertia dominates, and this means that once it moves forward, it keeps going forward unless a force stops it.

Entropy has a pronounced preference, and is central to the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy of an isolated system left to spontaneous evolution cannot decrease with time. As a result, isolated systems evolve toward thermodynamic equilibrium, where the entropy is highest. “High” entropy means that energy is more disordered or dispersed, while “low” entropy means that energy is more ordered or concentrated. A consequence of the second law of thermodynamics is that certain processes are irreversible.

Why did universe start so well organised? No idea!

The laws of motion mostly don’t care about the direction of time. Newton’s laws work the same forward or backward. Those molecular collisions are reversible, and technically the trajectory of a tennis ball trajectory is also reversible. Newton’s laws allow it, so why does it not happen? It is the macroscopic nature of the tennis ball and its flight. When the ball slows down, its kinetic energy is transferred into random molecular motion in the air, random vibrations in the floor of the court, and in heat. It’s energy is being spread across trillions and trillions of molecules. To see the tennis ball “un-slow” and fly back, those molecules would need to spontaneously all push in the same direction, all at the right time, and with the right forces. That corresponds to an unimaginably tiny fraction of possible micro-states.

Relativity does not contain an arrow of time. Space-time itself does not “flow”, and events just are.

Entropy introduces a direction (an arrow of time). Eggs break, and don’t unbreak, heat flows from hot to cold, tennis balls slow down, and don’t speed up.

Einstein tells us time is just another coordinate, but it’s entropy that gives time a direction. How can both be true? Are time and entropy connected?

If time moves as entropy increases, what happens at maximum entropy?

In Einstein’s special relativity, time is not universal. A clock moving at high speed relative will tick more slowly than a clock stationary on Earth.

This effect is called time dilation.

For a commercial jet flight the gain is only nanoseconds, but travelling at 90% the speed of light, 1 hour for the traveller corresponds to 2.29 hours on Earth. And for someone travelling at 99% the speed of light, 1 year for the traveller equals 7 years on Earth.

The idea of Einstein is that motion through space-time is shared between motion through space, and motion through time. The faster you move through space, the slower you move through time. And of course, the slower you move through space (sitting reading “We Have No Idea”) the faster time moves. I’m not totally convinced, because when I was reading “We Have No Idea”, I had the impression time had almost stopped. Although I’m not sure if reading the same thing three times counts.

Relativistic Correction to GPS

Let’s look at the relativistic correction to GPS (Global Positioning System). GPS satellite clocks do not tick at the same rate as clocks on Earth, and this is due to two competing relativistic effects.

Satellites move at about 3.9 km/s, so special relativity (velocity time dilation) tells us their onboard atomic clocks will run slower than Earth clocks by about 7 microseconds per day.

However, satellites orbit higher up in a weaker gravitational field, so general relativity (gravitational time dilation) tells us that their clocks run faster than clocks on Earth by about +45 microseconds per day.

So combined, satellite clocks tick faster than Earth clocks by about 38 microseconds per day, unless corrected.

That results in an error corresponds to 10–12 km per day, which would make GPS unusable.

So what happens is that satellite clocks are pre-offset before launch to tick slightly slower on the ground. But in addition, the GPS control segment continuously uploads clock and orbit corrections, and our receivers (e.g. iPhones and car navigation) also include the relativistic terms in their signal timing model.

However, less well known is something called the International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRF), which monitors the Earth by combining:

-

Very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI), a type of astronomical interferometry used in radio astronomy, checks the Earth’s orientation. By measuring delays from many quasars across the sky, VLBI determines the Earth’s rotation angle (UT1), polar motion (axis wobble), and polar motion (axis wobble), and nutation/precession

-

GNSS (surface deformation) which determines location (longitude, latitude, and altitude/elevation) to high precision (within a few centimetres to meters) using time signals transmitted along a line of sight by radio from satellites

-

Satellite laser ranging (SLR) which measure the distance to satellites in a geocentric orbit

-

Doppler Orbitography and Radiopositioning Integrated by Satellite (DORIS) for satellite orbits and for positioning

-

Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) which measures Earth’s gravity field anomalies.

I remember flying nears a VLBI station, and was told that they enforce radio silence zones, i.e. no mobile phones near the receivers, no Wi-Fi and bluetooth, no signals from electronics near the site.

How Many Dimensions Are There?

We have three physical dimension. We use them all the time, but do extra dimensions exist? What would we do with another spatial dimension? Could we even perceive additional dimensions? Who knows!

It doesn’t seem reasonably, but it has been suggested that additional dimensions might explain why gravity is so weak. Gravity could be diluted over many additional dimensions, often considered looped dimensions. So the idea is that gravity is strong, but gets diluted in these looped dimensions, before it gets to us. So “our” particle would appear not to move, even if it was actually moving in these other dimensions. Obviously that would mean that these looped dimensions must be small (smaller than a millimetre), otherwise we would see the effect.

Now comes the tricky bit. If our particle is moving in another dimension, it has momentum in these other dimensions, which means it has extra energy. But since it’s not moving in our dimension, that energy must be seen as an increase in mass. So the particle that was moving in another dimension would, in our dimension, appear heavier than a particle that was not moving in those other dimensions.

One idea is to knock stuff together, in the hope that a particle makes a quick trip into another dimension, and looks, in our dimension, as being heavier.

Another suggestion is that before particles take a trip into these other dimensions, and their gravity becomes much weaker, the particles should still have a stronger gravity. This might mean that it could be easier to create small black holes using a particle accelerator. However, it’s worth remembering that very high energy particles have been bombarding and colliding on Earth for eons, and no one has seen a small black hole yet.

And of course there is “string theory”, where our point-like particles are replaced by one-dimensional objects called strings. On distance scales larger than the string scale, a string acts like a particle, with its mass, charge, and other properties determined by the vibrational state of the string. It’s my understanding that in string theory, additional dimensions will also be very small loops.

So far there is no experimental evidence for additional loop dimensions. I’m not holding my breath.

Can We Travel Faster Than Light?

No, next chapter…

Hold it, why should there be a maximum? Why should it be 300 million metres per second?

Photons always travel at the speed of light, and never slow down. Yet we would find it increasingly difficult to approach that limit, and we would never get there.

What happens if you emit photons in a vacuum (with a torch), and you are also moving, well the photons will only travel at the speed of light. It does not matter which direction you are moving. It’s even weirder, because you and the torch can be travelling at different speeds in different directions, but the photons will always be travelling at the speed of light (in a vacuum), not slower or faster.

For us there is no such thing as absolute velocity, all velocities are relative to something, somewhere, and yet the speed limit of light applies to all relative velocities.

We can’t see anything travelling at more than the speed of light. Imagine firing photons pulses (with two torches) to two targets, each set at the same distance, left and right. Obviously, the photons will hit both targets at the same time. Or will they?

Let’s do the same experiment, but let’s position ourselves stationary in space, watching this experiment take place on the surface of the Earth as it rotates. Now once the pulses of light have been fired simultaneously, we see one target getting nearer to a torch, and the other moving further away from the other torch. So we will now see one pulse of photons hit one target before the other pulse hits its target.

So from a distance you see something different from if you were standing on Earth firing those pulses. Yet, both of you are right.

Also, instead of being stationary in space. you imagine you were moving, along the axis of those pulses of photons, then you see something different yet again.

So in three different configurations (geometries) each would see photons striking the targets at different times, and each would be right. We have to give up the idea that events (photons hitting the target) happen at the same time for everyone, everywhere.

So this same event (photons hitting targets), can have a different order when watching them at different speeds. And you can change the order of events, by simply changing your speed.

Remember when you were moving along the axis of photon beam. Lets imagine you are going faster and faster towards one of the targets, and away faster and faster from the other. If you could go faster than the speed of light, then you would see the photons hit the target, before they had left the torch.

But that would break the principle of causality. As such having a particular speed is one thing, but having a maximum is another. With that maximum we know that the universe causal (as already mentioned), but also “local”. What does “local” really mean, it means that things in one place can’t be affected by something coming from anywhere. No, things that affect a given place, must come from somewhere nearby. Because of that speed limit only things nearby can have a causal effect.

But why 300 million metres per second? No idea!

You might have noted the odd expression “in a vacuum” here and there. In fact the speed of light does depend upon the medium it is passing through, and it is lower if it is passing through air, glass, water, etc. Think that the photons will need to interact in some way with stuff along its path, and that will slow them down.

For example a muon (something similar to a heavier electron) can not go faster than the speed of light in a vacuum, but it can go fast than photons travelling through ice. It creates a kind of light boom (like a sonic boom), known as Cherenkov Radiation.

The Michelson and Morley Experiment

During

Cherenkov Radiation

During

Cosmic Rays

Everything, including everyone one of us, are constantly being bombarded from outer space.

We are being hit all the time by a vast number of photons in the form of visible light, infrared, UVA, UVB (partially blocked), UVC (mostly blocked), X-rays produced by stars, black holes, hot plasmas (mostly absorbed by atmosphere), deep space gamma-rays from supernovae, pulsars, gamma-ray bursts (unlikely to reach sea level), and some atmospheric secondary gamma rays produced by cosmic-ray showers (small background).

Then there are cosmic rays (charged particles) such as primary cosmic-ray protons (usually broken up high in atmosphere), primary helium nuclei (“alpha particles” usually stopped in the higher atmosphere), and heavy ions (carbon, iron, etc. which a very energetic, but none reach ground intact.

Then there are the secondary particles produced in the atmosphere. The dominate penetrating charge particle is the muons produced when cosmic rays strike air molecules. Typical ~100 per second pass through a human body.

Neutrons are produced by spallation in air showers. Typical, tens per second pass through a human body.

Electrons and positrons, as part of the electromagnetic shower component, are present but they are less penetrating than muons.

And top of the list are solar neutrinos, produced in nuclear fusion in the Sun. Typically ~10¹⁴ pass through a human body every second.Dark matter particles (hypothetical)

If dark matter is a particle, then billions may pass through a human body every second (speculative).

Naturally we are also bombarded by our local environment. This includes photons from any form of lighting and heating. Neutrons and alpha-particles are associated with natural radioactivity, and X-rays and gamma-rays with medical exams.

And it’s also worth mentioning that when flying at altitude, humans receive a much denser, more complex cosmic-ray shower including far more neutrons, gammas, electrons, and some surviving primary protons.

All that is the stuff we know, but there is stuff we don’t know…

In fact, there are also Ultra-High-Energy Cosmic Rays (UHECRs), which are cosmic rays with an energy greater than 1 EeV (1018 electronvolts, approximately 0.16 joules), far beyond both the rest mass and energies typical of other cosmic ray particles. The origin of these highest energy cosmic rays is not known, yet 500 million of these hit the Earth every year.

The Oh-My-God particle (as physicists dubbed it) was an ultra-high-energy cosmic ray detected on 15 October 1991 by the Fly’s Eye camera in Dugway Proving Ground, Utah, United States. As of 2026, it is the highest-energy cosmic ray ever observed. Its energy was estimated as (3.2±0.9)×1020 eV (320 exaelectronvolt). The particle’s energy was unexpected and called into question prevailing theories about the origin and propagation of cosmic rays.

The Amaterasu particle, named after the sun goddess in Japanese mythology, had an energy exceeding 240 exa–electronvolts (EeV). This single particle appears to have emerged, inexplicably, from the Local Void, an empty area of space bordering the Milky Way galaxy.

If the source had been far away, then the particles would have lost some energy, so a source of this strength must be quite near! But where?

And What About Anti-matter?

Paul Dirac, who formulated the Dirac equation, one of the most important results in physics, also predicted in 1931 the existence of antimatter. The Dirac equation is consistent with both the principles of quantum mechanics and the theory of special relativity, and was the first theory to fully account for special relativity in the context of quantum mechanics. The equation also implied the existence of a new form of matter, antimatter, previously unsuspected and unobserved. This would eventual lead to the discovery of the positron. For many this represents one of the great triumphs of theoretical physics.

Dirac would then propose that all particles have an anti-particle, right to quarks having anti-quarks.

There is also super-symmetry which suggests the existence of a symmetry between particles with integer spin (bosons) and particles with half-integer spin (fermions). It proposes that for every known particle, there exists a partner particle with different spin properties.

Of course, the question is why do we have all these anti-particles? What do they do? Are there more that we have not yet seen?

It is also true that a collision electron-positron explodes (annihilate each other) emitting high energy photons. And the same goes for quarks-antiquarks and muons and antimuons.

These are not really particles, but it’s more like two waves merging, and not colliding, and then disappearing in the form of another kind of particle (e.g. a very energetic photon).

But a particle only annihilates with its own antiparticle, and lots of other things are conserved (charge, number of quarks, etc.) Why? No one knows!

Remember electric charge is not created out of nothing or destroyed.

And in theory it’s possible to make up anti-neutrons and anti-protons from anti-quarks, and with that create anti-atoms, and even things like anti-water.

We already asked why do anti-particles exist? But we don’t know if they are really anti-, or if there a subtile differences, for example, do feel gravity in the same way, or is there an opposite way?

And of course, why are we made of matter and not anti-matter? And that leads to the question why are we in a universe and not an anti-universe? Maybe it’s because there is a lot more matter in our universe. If, at the Big Bang, there was as much matter as anti-matter, sure most of it would have managed by now to collide and annihilate. So it look like the universe, right from the Big Bang, had a preference for matter. Why?

Maybe what we see today was just the little bit extra matter, and that it’s true that most has been annihilated. Or maybe there was an equal quantity of matter and anti-matter, and something created more matter, or destroyed more anti-matter. If there had been just a little imbalance, maybe that resulted in the situation we see today. Or maybe there is an equal amount of matter and anti-matter, but it’s just not found in the same places.

Also charged particles that have anti-particles, but the photon does not have an anti-photon, and the same is true for gluon and Z boson.

Someone has made a hundred atoms of anti-hydrogen which lasted about 20 minutes.

One of the biggest questions today, is do anti-particles feel gravity in the same way as particles? Their electromagnetic, weak and strong forces are reversed, maybe thats also the case for gravity.

Big Bang

How can we speak about the creation of the universe, and above all how do we test our ideas?

Looking at the expansion of the universe, the equations suggest that all started with a single point, a singularity. That’s the suggestion using general relativity. But something so tightly compressed will certainly follow quantum mechanics. But who knows, and a singularity is perhaps not the best idea.

On top of that, if all started with that singularity, then the universe is now too big.

The time it takes for the light to get to us, tells us how far it has travelled, which tells us how long ago was that light emitted. This is the observable universe.

But also the universe is expanding faster and faster, so we are moving away from those sources of the first light of the universe. Now let’s think about this. Each year we see more light from further away, but we are also moving away from that light. But that light is travelling at the speed of light, so our horizon for the beginning of the universe should be expanding more rapidly than the stars around us are moving away. But then our horizon should be larger than our entire visible universe. So in theory our horizon for the beginning of the universe should be where there is nothing. But wherever we look, there are stars. So the universe is still bigger than the horizon for the beginning of the universe. So our universe can’t have started from a singularity (small point).

Next problem, the universe is too smooth. We are not in the centre of the universe, so why do we see it so smooth and uniform? Look at cosmic microwave background photons, everywhere is the same temperature. The photons are more than 14 billion years old, and should reflect more variation at the time of the Big Bang, but they don’t. They are all more of less the same distance away. How come they come from entirely different parts of the universe, yet had the time to mix and arrive more or less at the same temperature (energy). To do they must have mixed together travelling at faster than the speed of light.

If it all started with a Big Bang, then the universe is too big, and too smooth.

Unless at the Big Bang the universe (the fabric of space-time) expanded (inflation) much much faster than the speed of light. Only slightly later did it start to expand at less than the speed of light. This meant that the things in the universe obeyed the speed of light limit, but space itself expanded faster, making new space faster than light could traverse it. This space inflated was very, very fast, for a very, very short time, it was nearly instantaneously twenty-five orders of magnitude faster-than-light expansion. So now our observable universe is still inflating at the speed of light, but within a much larger inflated universe (space).

What about the smoothness, here we need to find a way for those photons to have mixed together, much closer than the distances would suggest. But with inflation, we can imagine that the photons were in fact very close, before being thrown out into an expanding space.

All this might sound absurd, but we have already seen that dark energy is create more space today. But what caused inflation? Who knows!

Extras????

quantum fluctuations during the inflation produced wrinkles that seeded stars and galaxies by gravitation

Fluctuations that derive from the randomness of quantum mechanics

The forces were balanced, but gravity just went of pulling on those fluctuations that emerged after inflation

However gravity is only strong enough to pull space flat. More would have started to pull all matter together, less would have failed

Big lumps compress and form planets and stars, but remember the other forces are working against gravity

Dark matter does not have those forces, so gravity is pulling dark matter in to smaller more dense masses

It could be that dark matter helped form our galaxies

They don’t collapse because they are spinning

Size of the Universe

The observable universe is just defined by the time light has taken to get to us – 13.8 billion light-years in every direction.

But space is expanding faster so it could up to 46.5 billion light-years.

Every year we see a larger universe (as a radius), and that means much more as a volume, with many more new stars.

Increasingly, scientists have noted that what we see is not evenly distributed, galaxies tend to group together, then some groups form clusters, and they tend to form superclusters. For example, “our” Milky Way is part of the Local Group, which it dominates along with the Andromeda Galaxy. The group is part of the Virgo Supercluster.

Some people ask why did stars clump together to create galaxies, whilst others ask why is there not some structure that groups together superclusters? It all depends on your perspective. If the universe was smooth and infinite then groups wouldn’t form, and if it was smooth and finite, it might all create just one big clump. The idea is that initially small quantum fluctuations created wrinkles during the inflation of space-time, and this seeded the creation of stars and galaxies (helped along with a bit of dark matter, and later still some dark energy).

And it was gravity that would eventually pull all those wrinkles together into denser and denser clumps. And the really interesting thing is that there is just enough matter in the universe to create a kind of flat space, but not enough to pull it all together. And now dark energy is expanding space itself, so everything is getting further apart.

And the fight is between gravity that wants to pull together even clumps of gas and dust, and the fact that particles don’t like to be pulled too near to each other. With Earth, gravity was strong enough to pull all the dust, rock and metals together to create a molten core. And gravity can go one step better and turn all that into a star, power by fusion. And hidden away behind this visible clumping together, dark matter is also giving gravity a helping hand. Dark matter does not have electromagnetic and the strong-force, but it can create a halo or ring of matter, that can then start to pull in more matter. It looks like this process was key to kick-starting galaxy formation in the early history of the universe. Without the help of dark matter gravity, the universe might still be waiting for its first galaxies.

We can see light that was emitted some 13.8 billion light-years ago, but that just means we can’t (yet) see objects that are further away. But we know that space can grow faster than the speed of light, and we can see things that were once inside our horizon, but are now past it. And that is up to 46.5 billon light-years ago, in every direction. Yes we can still see things that used to be closer to us. So the observable universe is bigger than the one we can see today, and our visible horizon is getting bigger every year.

But don’t forget that our universe is expanding, and on top of that dark energy is creating more space. It might be that the part we can see might never catch up with the full extent of the universe, and so there will be things we will never see. So we really don’t know just how big the universe really is. It could be finite, but in an infinite space. Or it could be finite in a finite space. Or the universe could be infinite.

When we look at the sky, and think that we can see all the stars going back 13.8 billion light-years ago, we have to ask why there is so much empty space?

This does create some really interesting questions. Why did space expand during the Big Bang? Why is it still expanding today? Why did “inflation” create a much bigger universe, or even why didn’t it create a little less space? Why is the speed of light a maximum, and why isn’t it slower or faster?

The emptiness of our universe is a fight between the speed of light and the expansion of space. We don’t know why either of these are as they are, but change the values and our night sky would change, possibly quite dramatically.

Theory of Everything

So the Theory of Everything started out as the unification of the four fundamental interactions, electromagnetism, strong and weak nuclear forces, and gravity. Today it’s more about having the simplest mathematical description of space and time, and all matter and forces in the universe. Simple means there is not a simpler description that is complete, and it should be deep, in the sense that it describes the universe at the lowest possible scale (i.e. the smallest building blocks).

It leaves open questions about what is the smallest level of distance that should be described (magnification), what are the smallest fundamental particles, and which are the most fundamental forces?

I must admit, that I can’t see anyone making much progress on this in my lifetime, so I didn’t make much effort to summarise what science will not be able to do in the next 50 years.

Are We Alone?

On this topic, my views are even clearer than on the Theory of Everything. I’m will to run the spellchecker on this paragraph, and that’s about it.