Our New Year trip for 2020 ran from late January 2020 to mid-March 2020 and involved 8 nights in Dubai and 43 nights in Phuket.

This webpage is a review of British Airways Airbus A320 Business Class used for a short-hop from our home airport to Heathrow Terminal 5, and back. Unlike many webpages which simply review a travel “experience”, what I’ve tried to do is to also look at some of the background issues related to the history of the A320, its construction, and it’s operation costs, etc.

We anticipated flying back from Heathrow Terminal 5 to our home airport on a BA A320. However, in fact we ended up flying back on a BA A319. So you will also see on this webpage a short review of that aircraft, however most of the webpage is dedicated to the A320.

Here is a really excellent video review of the business class in one of the older BA A320’s.

Flight to Heathrow Terminal 5

Let’s start with our actual trip.

A quick scan of a 10 day period showed that British Airways (BA) flew 10 different aircraft (all A320-232’s) on our short-hop route to Heathrow. The ages of the aircraft ranged from 8 to 17 years old.

However, for our hop into Heathrow the aircraft was much younger. On the day, our particular aircraft was only 21 months old (it had been delivered in April 2018).

The fact that our aircraft was relatively new probably meant that we had the ‘upgrades’ that were planned for newer deliveries (some people would say “more like downgrades”). Some of these changes will be mentioned later, but they all aimed to increase the number of economy seats available and reduce the overall weight (thus running cost).

You see mention of A320-nnn, where the A320-100 was the first variant (only 21 were built), and then there came the A320-200. The code A320-232, as mentioned above, is in fact an engine variant for the IAE V2500 two-shaft, high-bypass turbofan engine. The actual aircraft we flew into Heathrow was not a A320-232 but a A320-252N, where the ‘252N’ denotes a more recent engine option with the CFM LEAP-1A24.

Our flight left on time, and landed 22 minutes early, with a total flight time of 53 minutes (the expected flight time was 61 minutes). But we then “lost” time waiting for a free gate at Heathrow. Our aircraft was registered as G-TTNB (serial number 8139). In addition to the round trip to our departure point, the same aircraft had also done a round trip to Sofia earlier on the same day (a 3 hour trip each way).

I’m told that the official total flight time is from when the parking brake is released at the departure gate, until it is again put on at the arrival gate.

Boarding

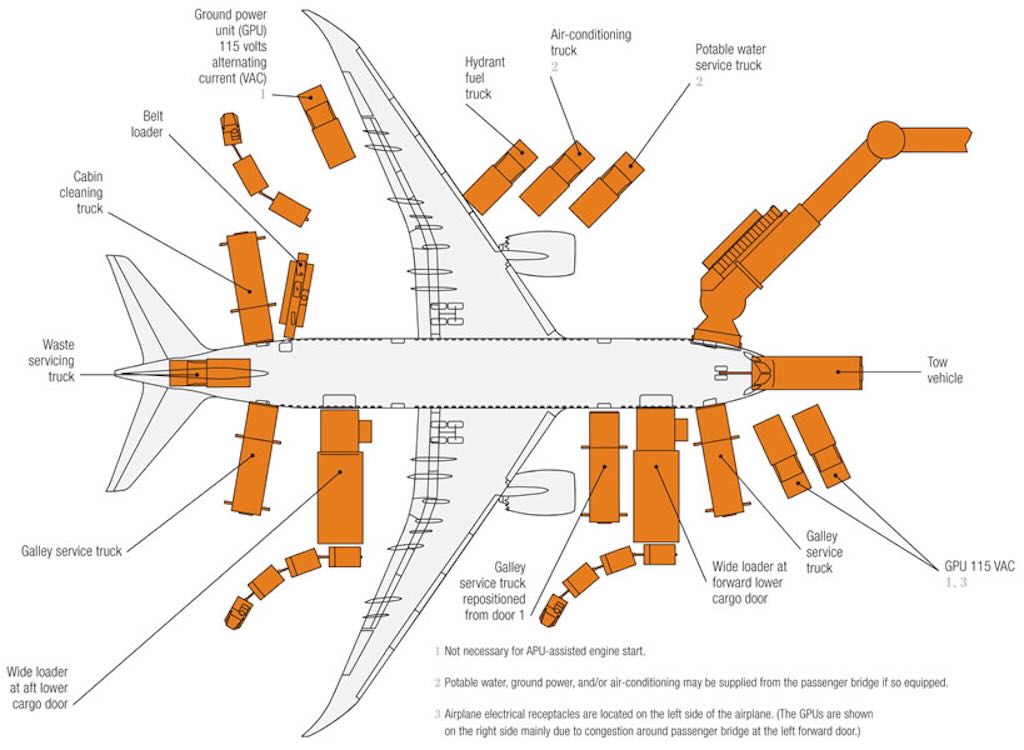

Below we can see a typical layout of an aircraft on the apron.

However our home airport is quite small, and the view from the business lounge is very limited. So with our evening flight all we could see was the tail.

With only the front entry point being used, boarding was made by passenger class. Classes 1-2-3 boarder first, and because we were flying BA Club Europe (Class 1) we were “invited” to board first. We were flying into London on a Sunday evening, so the plane looked quite full and many passengers appeared to be travelling for work, and just had a carry-on.

The jet-bridge

Despite leaving from a small airport, the aircraft was nevertheless serviced by a jet-bridge.

Overhead compartment

Our hand-luggage was a hard-shell travel suitcase, a hard-shell vanity case, a rucksack, a handbag and a walking stick (a slightly larger hard-shell suitcase had been check as baggage). There was plenty of space for the suitcase and vanity case in the overhead locker, and the rucksack fitted easily under the seat.

Business-class seating

We can see above a typical business class configuration (Club Europe in BA jargon). As far as I could see the seats configuration was the same as in economy, i.e. set three abreast. The difference was that in business there was a bit more leg room (I guess), and the middle seat of the three was condemned. Frankly the leg room was still limited in business class, and in particular if the person in front reclined their seat-back. I’ve read that seat spacing has been reduced so much in economy, that seats no longer recline “for safety reasons”.

The original A320 was configured for 150 seats, 12 ‘first’ class and 138 economy. This was increased to 164 seats in an all economy layouts, with a 79 cm seat pitch. Another early alternative was a 180 seat all economy layout with a 74 cm seat pitch.

So are all business class passengers actually sitting in economy seats, with economy comfort, economy trays, and just bit of added elbow space, and some extra leg room? The answer is yes, and no! Yes, in the sense that they are sitting in what were the old-style economy seats. However in the later deliveries of the A320 the old economy seats are replaced by the so-called “ultra-thin”, which now allow a 74 cm pitch (instead of the old 77-79 cm), but with improved leg room. These new seats only weight 9 kg! The down-side is that they no longer recline, the upside is that they have USB outlets. I’m told that all this resulted in the later A320’s carrying 180 seats, as opposed to 168 in the earlier versions. In BA jargon this is called “densification”. Frankly, being in the business class I didn’t bother to check on the economy seating arrangements.

BA implemented these seat changes in 2018, but both Air France and EasyJet had already adopted the “ultra-thin’s”. Interestingly, despite the reduced seat pitch, but thanks to the ultra-thin design, passengers were saying that they appeared to have more leg room. And to cap it all the pitch on the business class seats was now the same as the pitch previously used in the economy class (so down to 79 cm from 86 cm).

The welcome aboard

The boarding welcome was more or less non-existent. They checked the boarding card on my iPhone, and that was it. My wife had a crutch, but that certainly did not mean that they gave her any help.

Getting settled

Once installed in our seats, the cabin staff came around with fresh hot hand towels, which was nice. However, collecting the used hand towels was very hit-and-miss, and we were left with our cold towels until landing.

Safety briefing

The pre-flight safety demonstration was performed professionally, as you would have expected. It looked as if, in the business class, it was performed by the so-called Cabin Service Director (CSD), although I don’t remember anyone calling him that.

Take-off

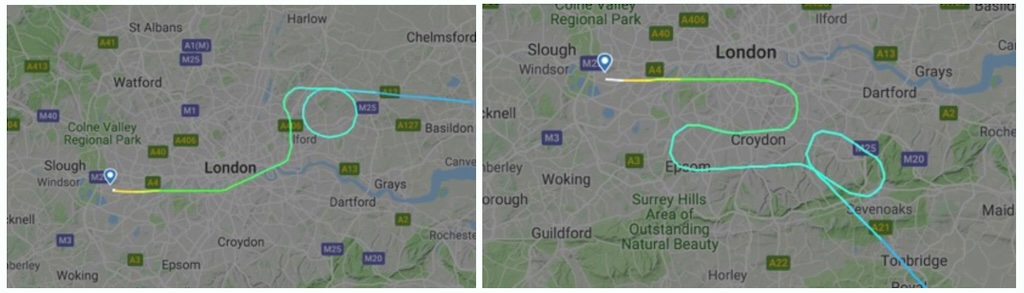

According to flightradar24 our short-hop generally leaves between 2 minutes and 28 minutes late, but always lands in Heathrow between 1 minute and 24 minutes early. This must be dependent in part on the holding patterns in Heathrow (see below).

There are a number of flight tracking websites, i.e. flightradar24 is one, flightaware is another.

Now you might ask why flying times appear to take longer today, yet aircraft are now faster, safer, quieter, and more fuel efficient than in the past (see this article in The Telegraph). This is all down to “schedule padding“, and Wikipedia tells us that this is time added to the duration of a flight to allow it to be “resilient to anticipated delays”. Which? looked at this and found schedule padding to be very common today, since airlines try to avoid delays having a knock-on effect throughout the day. It also enables airlines to show (and sell) great punctuality records. We also have to remember that in the airline industry arriving up to 15 minutes late is still “on time”, in part because arrival does not mean landing but is when the parking break is applied at the arrival gate. There are good reasons for some padding since both air space and airports are more congested. Another reason is flying slower reduces fuel consumption. Of course it also means that airlines have to pay less compensation for flight delays.

Our aircraft actually took-off on time, and landed 53 minutes later. According to the actual flight path we came in with almost no holding over London. However we lost 10 minutes waiting for a free gate at Heathrow.

In-flight

After the safety demonstration and the food there was not much time for anything else. In fact the cabin crew came round asking if we wanted to eat, or just have a drink. Almost everyone went for something to eat.

I really did not notice, but I had read that BA had dropped the “duty free purchases”. It would appear that the rear toilet has been removed to fit in an extra row of economy seats. A new toilet has been built into the back wall of the galley, using the space previously used by the duty free trolley.

The drive for economy has reached such a point with BA that the number of Club Europe (business class) seats is capped because the Club galley space can only take 48 trays (on the basis one tray, one seat). Another economy (weight saving) on the later A320’s is that there are no drop-down monitors, so no safety demonstration video nor “moving map”. And due to the re-arrangements in the economy galley there is no longer any waste facilities or potable water. So requests for free tap water require a visit to the Club galley, and all waste is also carried through and stored in the Club galley.

Food & drink

BA short-haul business dining options range from breakfast, to snacks and meals. Our snack-meal was a shrimp and avocado salad, coleslaw, a small chocolate mousse, and a small bottle of Mârcon Villages. It came with a cotton napkin, metal cutlery, and hot bread. The below photograph shows a very similar offering.

As far as I could see about half of the business seats were occupied, so food service was quick and quite efficient. The cabin crew (CC) even had time to make a second round offering more bread.

One oddity was the way wines were described. The CC offered the grape rather than the type of wine. I wanted a white wine, and was offered either Chardonnay or a Sauvignon Blanc. When I hesitated I was told French or New Zealand. So I went with French, and got a simple Mâcon Villages. I must say it was not bad (and the temperature was perfect), but the next day Emirates would offer me a Pouilly-Fuissé, a top-of-the-range Mâconnais.

On a BA economy short-haul (Euro Traveller in BA jargon) food is no longer offered, but passengers can buy M&S food items, coffee, tea, etc.

In-flight entertainment

None, just the usual tatty flight magazines.

The toilets

Not visited.

Landing at Heathrow

Landing was perfect, although we had to wait 10 minutes for a free gate at Terminal 5.

Disembarking

Disembarking was over a single jet-bridge. However many of the passages appeared to know where they were going and were in a hurry. They just pushed past dragging their carry-ons. We were travelling on Sunday evening, and my guess is that more than half of the passengers just had a carry-on.

Return flight from Heathrow Terminal 5

Our return flight was made under completely different circumstances. In mid-March 2020 the Coronavirus disease 2019 had been declared a pandemic.

We were picked up from the BA lounge in Terminal 5 by a woman looking after our assisted boarding. However, this time my wife not only had a wheelchair but they actually laid on a ambulift, a special lift to access the aircraft.

This was an experience in itself. They are used when aircraft are not accessed through a sky-bridge. They did actually ask my wife if she could climb up the external stairs, and she replied positively. But given that the ambulift had been ordered everyone felt that she should use it. The staff on the gate, on the ambulift, and on the aircraft were great.

This time our return flight to our home airport was on a A319-131 registered as G-EUOG (serial number 1594). It even has its own video of a landing at Heathrow. This aircraft had already flown London-Amsterdam-London, before flying a round trip to our home airport. Looking at its past schedule, it’s used for short-haul flights to Brussels, Oslo, Hamburg, Basel, Zurich, Amsterdam, Berlin, etc. It left Heathrow 18 minutes late, but still landed 20 minutes early.

After we landed back home, the return trip to Heathrow was so empty that it left our home airport 10 minutes early, and arrive back at Heathrow a full 37 minutes early!

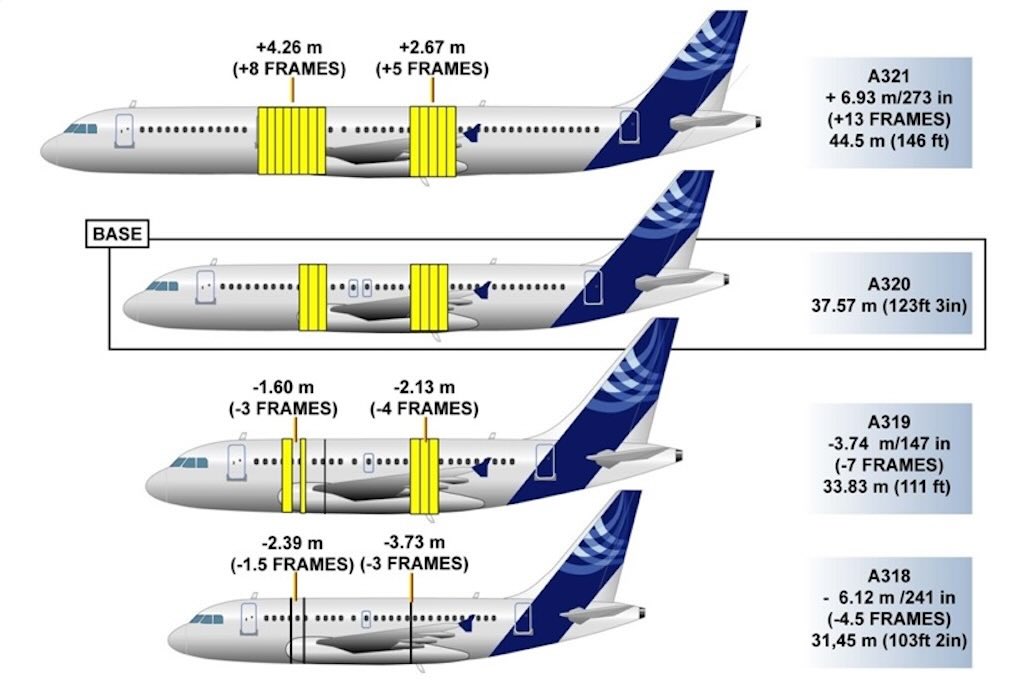

The A319 is a shortened fuselage variant of the A320 that entered into service in 1996 (so it followed on from the A320 and A321). As far as I can see the ‘131’ code represents a specific engine version, with the IAE V2522-A5. The International Aero Engines (IAE) consortium produces a two-shaft high-bypass turbofan engine called the IAE V2500. The ‘A5’ was a version with increased thrust designed for the A321-200, and the ‘V2522’ was a followup ‘derated’ version for the A319 introduced in 1997. The ‘derated’ means an engine with a reduced thrust designed to meet a certain noise compliancy.

Our A319-131 was delivered to BA on October 2001, so it was 18½ years old. But it was last through its 3-week maintenance program in July 2019.

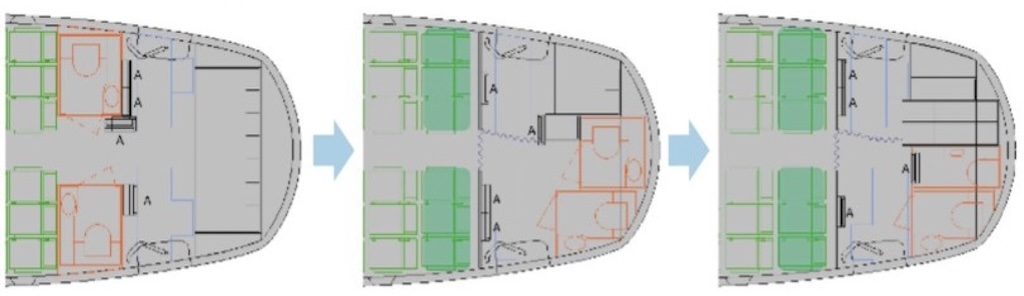

The aircraft operates a CY143 seating plan, i.e. a 143-seat all economy configuration for charter flights, and between two and eight rows of business class seats on scheduled flights (it has a movable curtain divider). As a point of comparison BA operates four different seat configurations on the A320 and A320neo.

The A319 seats were the same as in the A320. They were the Pinnacle short-haul type installed in March 2015 (the model was first introduced in 2014 as a ‘slimline’). At the time they were introduced on both economy (Euro Traveller) and business class (Club Europe) with the same seat pitch of around 30″ (it was previously 34″ in business). So the only difference is that the configuration is 3-3 in economy, and 2-2 in business with the middle seat (B and E) blocked out with a tray table. In fact the business configuration can be very rapidly converted into the economy configuration. You can remove very quickly the trays that block the middle seats, and they slip under the seat and still allow access to the lifejacket. Then you remove the divider, and you are left with a full economy cabin.

The A320 now has a new type of non-reclining Recaro seat that allows the capacity of the aircraft to be increased from 169 seats to 180 (and even more with other cabin reconfigurations). And the A320neo can be delivered with a seat capacity of up to 218. One reviewer mentions these new seats as being “a fresh layer of hell”, although others have noted that they actually appear to add an additional sense of space for passengers.

Quality of flight

As far as could see there were only 4 business passengers, although I think 3 other passengers were ‘upgraded’ to business class at take-off. There was no in-flight entertainment, and no overhead screens, but the cabin service was impeccable. Having spent nearly 3 hours in the BA lounge in Terminal 5 we decided not to take the snack offered.

Landing was perfectly performed, so not much else to write.

This particular aircraft was involved in a ‘serious incident‘ at Heathrow on 2 October 2019. It is interesting to mention this because it highlights the complexity of what most passengers would consider a routine flight. The aircraft was to make a short flight to Leeds Bradford Airport, carrying 96 passengers and 6 crew. They had made the ‘performance data calculation’ for joining the runway at a particular intersection, and on having 3,380 m available. But for some reason the Pilot Monitoring (PM) mistakenly asked to use a different runway intersection, leaving only 2,702 m for take-off. This was agreed by air traffic control (ATC) and they were cleared for take-off, leaving them little time to complete their pre-departure duties. The take-off was unremarkable, but the error was detected during the post-flight debrief. This could have been a “significant event”, but the aircraft was light, with a limited payload and fuel, so take-off performance had not been compromised.

Video reviews of the Airbus A320

What you have read above is my review of our short-hop business class flight on a British Airways Airbus A320 from my home city into Heathrow, London, and the return flight on a A319. There are a multitude of written reviews on the different seating options in a A320, but more interestingly there are also some video reviews. Let’s kick-off with a review of a US domestic first class trip in an A320, then onto this British Airways Club Europe (Business Class), and closing with the Lufthansa A320 Economy Class.

Pilot an Airbus A320

As an interesting addition to the passenger viewpoints expressed above, what about the view of the pilot? Let’s start with a look at a video on the ‘facts you need to know’ about the Airbus A320, and then move on the so-called ‘outside check’ or ‘walk around’ and then (finally) on to the Airbus A320 cockpit video for a trip to Tenerife. And I love this video on an A320 night landing in Nice, France. And there is also a 60 minute long cockpit view of a A319 flight from Zurich to Larnaca.

This video has the rather barbaric title ‘FSiPanel 2017 FSLabs A320 RNAV 02 in Kathmandu’. It’s a video about a simulator package, which in this video describes how you might train a pilot to make a landing in Kathmandu flying the A320. The jargon is bit technical but it will give you a general idea of the cockpit (starting 5:15), setting up (8:33), flying (10:48), and landing (17:50).

Now if you are really interested in following a complete simulation of a flight from Gatwick to Lisbon in an A320, have a look at this sequence of video’s, FlightFactor A320 Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5. If you hunt around you can find quite a series of flight simulator runs with the A320, including comparisons between different flight simulator packages.

A good source of basic information on the A320 displays and panels is this website, and Smart Cockpit has an extensive list of documentation on the A320 (if you are prepared to sit through the ads).

History of the Airbus A320

The Airbus A320 is a short- to medium-range, narrow-body, twin engine aircraft manufactured by Airbus. Today there are two versions of the A320 the A320neo (new engine option), meaning the older A320’s are called the A320ceo (current engine option). The A320 was the ‘original’ member of the A320 family (1984), and in 1994 the stretched version A321 version was introduced. Later came a first shrinking with the A319 (1996), and then a second shrinking with the A318 (2003).

In one of the maintenance manuals it stated that the A32x family is the world’s best selling single-aisle aircraft. A A320 takes off or lands somewhere in the world every 2.5 seconds of every day, and the A320 family has logged more than 50 million flight cycles since entering into service and records a best-in-class dispatch reliability of 99.7%.

A ‘flight cycle’ is any complete running of an engine until it is shutdown. This can be from take-off to landing, but also any other start-stop such as an aborted take-off is considered a flight cycle.

The A320 has quite a number of ‘firsts’ to its name. In many ways its design and construction is quite conventional, however it uses a considerable amount of composite materials. The fin and horizontal tailplane are constructed of composites and well as the flaps, spoilers, ailerons, engine cowls, and the leading and trailing edge access panels.

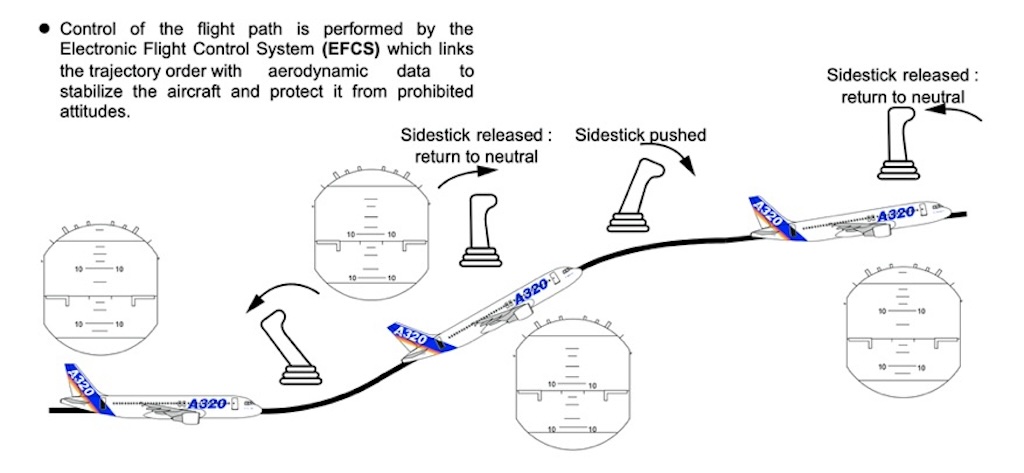

In addition I think the A320 was also the first commercial aircraft to use fly-by-wire flight controls for the elevators, ailerons, spoilers, tailplane trim, slat and flaps, speed brakes, trim in yaw, and engine controls. What does that mean in practice? It means that the aerodynamic surfaces are positioned relative to the pilot’s command by electronic signals sent via aircraft wiring from the flight control computers to hydraulic actuators.

Another first for the A320 is that the A320neo is the only western-built single-aisle that offers an engine choice, either the CFM International LEAP 1A (the LEAP 1A26 variant) or the Pratt & Whitney PW1100G-JM (PW1127G-JM variant). The engine options are not the only difference, the A320neo has a new cabin and rear galley configuration, greater seating capacity, Sharklet wingtips, etc. The two new engines provide an estimated 15% fuel burn improvement over the older engines, but they are heavier and bigger and produce more drag, so this reduces the improvement. But in addition the Sharklet wingtips produce about a 3% fuel burn economy, so the net improvement is still somewhere near 15%. And the redesign of the toilets and galley space allows an additional row of seat, increasing the capacity from 180 to 186. The newer engines also have fewer moving parts, which should have a positive impact on maintenance costs. We also tend to forget that a 15% fuel saving, and an aircraft additional flight range of nearly 1,000 km, means 3,600 tonnes less CO2 per aircraft per year, together with a more than 10% reduction of NOx emissions and reduced engine noise.

One of the most impressive and unique features of the Airbus A320 family is the international effort that comes together. Initially the partners in UK, Germany and France all wanted a bigger part of the cake. This was a question of both money and prestige, and it was only in 1984 that everyone agreed how to produce an initial order of 96 aircraft from 5 different carriers. People tend not to know that the A32x is also now assembled in Tianjin in China and in Mobile in Alabama.

Below we can see the BA A320 type 232 (or A230-232) where the ‘232’ designates a specific engine version. If you are interested in Airbus version codes, check this out. The A320-232 is the version introduced in 1993 with an International Aero Engine V2500 turbofan.

In 2020 British Airways owned 89 Airbus A320’s of which 77 were in operation, 10 A320neo and 67 A320-200’s. Also in that 89 they had five A320-100‘s and five A320-200’s in storage. In addition BA had two other A320-200’s, one destined for scrap (or already scrapped) and one operated by Virgin Australia since 2013.

According to Wikipedia the A320 has two variants, the A320-100 and the A320-200. Airbus only produced 21 A320-100’s, and BA still had 5 of them in storage. The change from the -100 to -200 designation was due to the introduction of wingtip fences and an increased fuel capacity for increased range. So to all intents and purposes the A320-200 is the same as the A320ceo, in that it was the ‘standard’ or original A320 powered by two turbofan CFM International CFM56 (the same engine used in the Boeing 737). The only real major upgrade of the A320 was the introduction of the re-engined A320neo in 2014. This is not to say that enhancements and different engine versions did not occur at regular intervals (as can be seen in the Wikipedia article on the A320 family).

The life of an aircraft can be quite varied. Let’s take an Airbus A320-200 manufactured in 1999, serial number 999 (I-BIKE). It was a A320-214, first introduced in 1995 and equipped with a new variant of the turbofan CFM-56. It took its initial flight registered as F-WWBZ in April 1999, this must be a manufacturers registration used and re-used for testing new aircraft awaiting delivery. This particular aircraft was delivered to Alitalia in May 1999 and registered as I-BIKE. I-BIKE was one of 38 A320’s bought by Alitalia and used on routes such as Milan-Dusseldorf, Milan-Amsterdam, Milan-Rome, and Milan-London (I-BIKE was named the Franz Liszt). If you are really interested in looking into the details, check out this ‘incident’ report for I-BIKE during Milan-London in 2005. The aircraft was withdrawn from service in May 2013 and put in storage at the airport LDE at Lourdes in France. In August 2013 it was re-registered as OE-IJC with the Austrian airline Jetcom (which appears to no longer be operating). In April 2015 the aircraft was re-registered again as UR-CMI with the Ukrainian Dart airline, before being put in storage in April 2015 at the airport MPL in Montpellier in France (Dart ceased operations in 2018). In early August 2015 it arrived at the airport THR in Teheran in Iran for storage, but within a week it was re-registered yet again as EP-ZAT with Zagros Airlines. In Iran EP-ZAT was used for the route Mashad in Iran to Al Najaf in Iraq. According to one report EP-ZAT was now painted (2020) in the ‘Kish Dolphin Park‘ colours, after the first dolphinarium in Iran, and is now flying Mashad to Kish Island.

Reading about the life of I-BIKE clearly shows that an aircraft such as the A320 can have quite a varied life. Companies can own their aircraft or lease them. Companies might lease because they need more aircraft but don’t have the cash to buy.

ACMI is an acronym that stands for ‘Aircraft, Crew, Maintenance, Insurance’ which are the four pillars of leasing by one operator to another. This type of “wet” lease means that the aircraft is airworthy and ready to fly immediately the contract is signed (a “dry” lease is just for the aircraft). The lessee brands the flight and sells tickets, but the owner does the rest (e.g. flight planning, crew training and rosters, maintenance, etc.). A “wet” lease is used when a company has no backup aircraft, or by virtual operators such as holiday charter companies. It can also be used to optimise fleet availability and cover big seasonal variations. When a company collapses new routes suddenly appear, and companies might “wet” lease because they don’t have free aircraft and crews and can’t exploit immediately those new routes. The only problem with a ACMI lease is that it is the most expensive way to get an aircraft. And remember if you want to buy a new aircraft you might have to wait years for delivery.

With the recent problem with the Boeing 737 MAX many companies had crews, etc. but no planes, so they “dry” leased some, i.e. just rented the aircraft.

There exists also a “damp” lease, where a company leases some but not all of the ACMI features, e.g. they may have newly recruited crews, but no additional pilots.

The best figures I’ve seen (2020) for a ACMI “wet” lease of a A320 was $687,500 per month. The lease was based upon what is called a “block hour” (chock-to-chock) lease rate of $2750, and 250 hours/month. It included the aircraft, crew and crew scheduling, maintenance and ground engineering, third-party insurance, and operation flight plans. It excluded fuel, landing and terminal charges, passenger and cargo handling, airport taxes, parking and push-back services, etc., all dry goods, catering, cabin cleaning and servicing, airport security, over-flight permits, custom taxes, travel costs for crew, hangar space, spare parts, insurance for passengers and baggage, etc….

Today something between 40% and 50% of all aircraft are leased, representing more than 12,000 aircraft. But this is not all the story. Most leasing companies own narrow-body aircraft such as the A320 or Boeing 737. They provide the best profit margins and cost the least when switching lessees. If you buy a single A320 it could cost you more than $100 million. Lease companies buy in bulk with big discounts, and they maintain well the aircraft for re-sale. Recently one report suggested that discounts of around 55% could be obtained for a new Boeing 787-9 (that’s $132 million instead of $292 million). If the lessor can’t sell the old aircraft, they can break it down for spare parts. The risks are also high, since lessees go bankrupt and there is an overcapacity in the leasing market.

Just to put a few figures on the idea of aircraft leasing, in 2018 the top 25 lease operators owned nearly 8,000 aircraft, with just over 300 in storage, and another 2,800 on order. The biggest lease operator had more than 1,000 aircraft leased to more than 200 different operators. Less than 40 aircraft were in storage, and they had placed orders for nearly 400 new aircraft.

I’m told that many airline companies keep their aircraft off their balance sheet by placing them in a separate legal entity. The lessor receives cash from the leasing of the aircraft, and attracts investors because the aircraft is a solid collateral that could be repossessed if necessary. The lessee can deduct the full rental payment as an expense. The lease is not a debt on the balance sheet, but depreciation cannot be deducted nor equity created because the aircraft is not on the balance sheet. It appears that there are also hybrid options where the lessee can deduct depreciation, where the lease is considered a debt, and where the lessee can later decide to acquire ownership or not.

The top six aircraft leasing companies registered a return on equity (ROE) for 2015 of between 6.9% and 19.5%.

Fuel economy

When we see an aircraft parked at a gate waiting to be boarded, what do we see? There is an old saying “An aircraft is nothing more than a million spare parts flying in close formation“. And I might also mention John Glenn’s famous “sitting on top of 2 million parts, all built by the lowest bidder“.

What we don’t see are the thousands of “assemblies” or “sub-assemblies” that are ‘parts’ that are overhauled, repaired, or in many cases simply replaced. Some people have guessed that an A320 has somewhere between 400,000 and 1.2 million parts, depending on how we define “part”. Others have noted that Airbus catalogues 2.5 million part numbers produced by 1,500 companies from 30 countries. And this does not count the fact that a “part” can be made of up a number of individual “bits”, making up a catalogued “part”. For example, someone noted that a large wide-body could have as many as 6 million parts, half of which are fasteners (rivets). Then there are parts that are not really “bits” such as 274 km of wiring or the 8 km of tubing, or 66,150 kg of high-strength aluminium.

So to cut a long story short, what we are looking at is a fantastic piece of engineering. We start with what is called the “Manufacturer Minimum Weight” (just over 37 tonnes), which is the minimum weight for which the aircraft is in compliance with its flight requirements (i.e. its considered technically airworthy). This is also often called the “Manufacturer Empty Weight” or the weight ‘as built’. This includes the structure, power plants, furnishings, and all necessary equipment that is “integral” to the aircraft. Then we have to add all sorts of fluids, i.e. engine oil, engine coolant, water, hydraulic fluid and something called unusable fuel. To this is added what are called “standard items” and “operator items”, which then make up the “Operating Empty Weight” (around 41½ tonnes). So far we have not added usable fuel, baggage, passengers, etc. The maximum fuel capacity of an A320 is nearly 24,000 litres, or about 19.5 tonnes. The potential weight of the all passengers (186), crew (8) and all allowed carry-on baggage is about 17.6 tonnes, excluding the 9.4 tonnes maximum cargo capacity (i.e. check-in baggage). So in theory this could produce a total weight of our A320 of about 88 tonnes. However this exceeds the maximum allowable weight of an A320. This maximum is for a full aircraft of full-weight men with maximum check-in and carry-on baggage, and full fuel tanks. Also there may be no rational for carrying full fuel tanks on short routes, when the recommendation is to just carry enough fuel for the sector being flown.

The “Aircraft Gross Weight” (or “all-up” weight) is the total weight at any moment on the ground or in the air, and is made up of Zero-Fuel Weight (the total weight of the aircraft minus all usable fuel) added to the usable fuel, remembering that the weight of usable fuel will change during the flight. The “Aircraft Gross Weight” on the ground cannot exceed the “Maximum Taxi Weight”, which for an A320 is 77.4 tonnes. In addition there is also a “Maximum Take Off Weight” and a “Maximum Landing Weight”, which for the A320 are 77 tonnes and 66 tonnes respectively.

In one report there was a very thought provoking statistic. Lufthansa had calculated that for 2016 and for its entire fleet, it cost “3.85 litres per 100 passenger kilometres”. Jet fuel prices varied from under $40/barrel up to just over $60/barrel during 2016 (157 litres/barrel).

When we make a trip the carrier will need to understand the total cost, including both fixed and variable costs. In its most simple form this includes the cost of fuel (/kg), the time-related cost per minute of flight, the fixed costs independent of time, the fuel used for the trip, and the time of the trip. The time-related costs include the hourly maintenance costs, the flight and cabin crew costs per hour, and the marginal depreciation or leasing costs per (extra) flying hour. These type of costs are reduced the faster the aircraft is flown, simply because you want to maximise the miles flown for time-related components between inspections. But the faster you go, fuel burn increases. To limit fuel consumption, the aircraft should be flown more slowly. So everything is about balancing time-costs against fuel costs. Clearly this discussion is for a given situation, however costs will be affected by the distance flown, the payload, the cruising speed, weather, etc.

There are other costs which include dealing with passenger dissatisfaction, with missed connections, and with landing fees and ground service costs.

And of course everything changes depending upon the how the fuel cost fluctuates, and its all about trading increased trip fuel for reduced trip time, or vice-versa.

We have already mentioned a little about the running costs of an A320. Today a new A320 will cost around $101 million. On top of that you need to factor in the operating costs, ca. 40% crew, ca. 20% for fuel, ca. 15% on maintenance, and the remaining 25% for navigation, ground support and landing fees. The real meaning of a 15% reduction in fuel burn depends a lot on the price of fuel, payloads, the utilisation (flight hours, sector lengths, flight cycles with take-off’s and landings), but based upon a full price of $2/gallon and an average utilisation of 9 flight-hours/day, a 15% saving on fuel could represent $600,000 per year. Maintenance costs of engines are either those associated with “performance restoration” (overhaul every 5-8 years), or replacement of “life limited parts” which normally would take place once every 10 years. It is estimated that the newer ‘neo’ engines will also save about 15% on maintenance costs. If you want to learn more about these new A320 engines checkout this article.

Side-stick vs. Yoke

This sounds a bit barbaric, are these alternative types of torture instruments? No, the side-stick is a kind of joystick that is often found on fly-by-wire (FBW) electronic flight control systems.

On numerous aircraft, including the A320 and subsequent Airbus aircraft, it is an alternative to the more conventional “centre stick“. The “centre stick” replaced the traditional yoke, but it retained the connection between the pilot’s and co-pilot’s control. The Airbus side-stick is located at the side of the pilot, and the pilot’s and co-pilot’s sticks are independent (the electronic flight control system manages the relationship between the two side-sticks).

The vast majority of aircraft, big and small, have (had in 2020) mechanical connections between the pilot’s stick, or yoke, and the flight control surfaces – the ailerons for roll, elevator for pitch, and the rudder for yaw. When a pilot moves the yoke, not only will the linked co-pilot’s yoke move, but the pilot will feel the response of the control surfaces.

Decades ago, beginning with Concorde, fly-by-wire (FBW) flight control systems began appearing in large, commercial aircraft. Simply put, FBW replaces a mechanical connection from the cockpit with an electronic one. The pilot commands a roll by moving the stick, which is translated into a digital signal, sent by wire to an actuator attached to the aileron, which then moves. All Airbus jets from the A320 to the A380 are full FBW, as are Boeing’s 777 and 787. With FBW, flight system engineers can develop software that adapts to different phases of flight, along with flight envelope protections. In theory, the plane can protect itself, and its passengers, from extreme situations or pilot inputs.

The two airframers (Boeing and Airbus) went down different paths in developing the pilots’ FBW control system. The pilots are essentially “flying” the FBW software installed in the flight control computers, which interpret the control inputs and send the signals on. So, Boeing decided to maintain the legacy with linked control columns and yokes. In those planes, a pilot can see the controls move, whether it’s the other pilot or the autopilot flying. Airbus went a different route, and opened up the cockpit by using side-sticks, mounted just below the side windows, beside each pilots’ seat. The Airbus side-sticks, and those in other similar side-stick equipped FBW aircraft are passive. The pilots don’t get any feedback, and the two sticks aren’t linked. The sticks don’t move when the autopilot is flying, either. And with millions and millions and millions of safe, side-stick flight hours, it’s clear that this is a technology that works.

There are literally hundreds of webpages about preferences for “centre stick” or “side stick”, and as with all preferences, there is no definitive answer. Although there is now an active “side-stick” option, which may change things in the longterm.