This post is about what happened day-by-day on a whale watching trip to the Faial in the Azores.

If you want some light background reading check out “Whalers turn their skills to whale watching“.

13 May 2025 (Day 1) - Travel to the island of Faial, and meeting the group

I had pre-booked the flight to Faial (airport Horta) with Azores Airlines. I had also decided to spend some days in Lisbon, and had booked a room in the “Hotel Pessoa”. In fact, I had booked a stay in the same hotel both before and after my trip to the Azores, and I had left my car safe in their underground garage.

See my review “Hotel – Pessoa, Lisbon“.

My flight to Horta was at 07:45, with a check-in opening at 06:00. The hotel mentioned that the trip could take up to 45 minutes depending upon traffic. The hotel booked me a car to the airport for 05:15, for €25.

On Goggle Maps the trip to the airport was estimated to take at least 25 minutes (approx. 8 km). In reality there was no traffic, but the airport was surprisingly crowded. Having bought priority access I was able to check-in and go through security so quickly that I was standing waiting to enter the lounge at 05:50.

There are two lounges in the airport, the TAP lounge which opens at 05:00, and for all other carriers there is the ANA lounge, which opens at 06:00.

See my review of “Humberto Delgado Airport, Lisbon“, which includes a mention of the ANA lounge.

The instructions from New Scientist/Intrepid was to collect baggage in Horta and look for the welcome/transport.

The Horta airport is so small this proved very easy. I met three other people in the group, and learned that we would be six in all.

See my review of “Azores Airlines and Horta Airport, Faial“.

Also check out “Planning Whale Watching in the Azores“.

Above we have an unusual view of Horta. It’s located on the southeastern coast of Faial, facing the Pico Channel, a narrow strait (just 8 km across) that separates Faial from Pico Island. The town is nestled between the sea and the interior volcanic ridges, with easy maritime access.

Located on the far side of town is the main commercial port, which handles ferries, cargo, and inter-island transport. Central we see the Marina da Horta, more sheltered, which is one of the most famous marinas in the Atlantic. It is a traditional stopover for transatlantic yachts (in 2022 the marina recorded 1,131 yacht arrivals). Then there is Porto Pim, a smaller harbour just southwest of the main town, historically important for whaling and local fishing (we would visit the whaling museum the next day).

The very visible rock outcrop is Monte da Guia and Monte Queimado, a double volcanic cone. In the photo we see what looks like a small island inside the volcano, but in fact the shadow hides the fact that the land is connected to the wall of the volcano defining two nested lakes.

Monte da Guia is dormant and is by far the larger, rising just over 145 meters. It forms the major part of the peninsula. It looks over the Caldeirinhas, two nested crater lakes inside the cone, with one being a submerged volcanic crater. Monte da Guia is an early submarine volcano that helped shape Faial’s southern coast.

Monte Queimado is a younger much smaller volcanic cone, and means “Burnt Mountain” referencing its dark, scorched appearance. In the photo it sits behind Monte da Guia, and appears to form a bridge with the main island. In fact it forms the northern half of the twin-cone structure, and it creates a sheltered bay for Porto Pim.

We took a short drive to the Arozes Faial Garden, but could not check-in until after 14:00. So the group (of four) went for a walk and found something to eat at the “Pastelaria Ideal” on Largo Duque de Ávila e Bolama. This is part of the waterfront promenade, and the “pastelaria” (cake shop) appeared quite popular with locals.

Quoting one past reviewer “Came here for a quick bite, was one of the only places that was open. A lot of locals here, service is super quick, portions are decent and the prices insanely reasonable“.

See my review of the hotel Arozes Faial Garden.

At 18:00 the group met with the Intrepid group leader Armando, and the New Scientist expert, Dr. Russell Arnott (plus lots of links on name, see research profile).

We also met two additional members of the group that had a different travel agenda. The final group (the “pod”) consisted of Martin (Swedish), Judith, Linda, Jan (all from UK), Cori (US) and myself.

Russell presented a very accessible and entertaining introduction to the Azores and whale watching. This was followed by a dinner in the hotel, that proved abundant but difficult to digest.

14 May 2025 (Day 2) - Exploring Faial

The original planning involved a trip out to sea, to observe whales, etc.

However, the weather was both overcast, and windy with rain (16°C to 20°C, 17-50 km/hr wind, 6-10 mm rain/hour at times).

In these conditions it was impossible to see any animals. The “vigias” (watchmen or lookouts) can’t see whales in the distance because of the mist, and/or rain, and/or ‘choppy‘ sea.

“Choppy” has no formal definition, but it means moderately rough and irregular, with short, steep waves caused by wind. The surface looks broken or patchy, often white-capped, making spotting animals on the surface very difficult or impossible.

The reality is that whales, dolphins, fish, etc., are all animals, and whales and dolphins are actually mammals. However, during the week the team usually refereed to them simply as “animals”, I guess to distinguish them as different from birds or fish.

On Faial Island in the Azores, traditional land-based whale spotters, known as “vigias“, still play a crucial role in whale watching and research operations, continuing a method developed during the whaling era.

One possible view (often questioned) is that “vigias” were angels, either as Holy Watchers, or “Grigori” who were the Watchers. These were 200 angels who abandoned their original home in heaven and descended to earth and mingled with the daughters of men. It is said that they would take many daughters of men as they desired, and if they were punished for it, they would all accept the punishment equally. The Holy Watchers were Uriel, Raphael, Raguel, Michael, Sarakiel, and Gabriel.

Above we can see one of the older traditional whale spotters small white lookout points strategically placed on elevated cliffs around the island’s coastline. We will come back to the role of the spotters later, because we were able to visit one of the huts and chat with a spotter.

So given the poor weather it was decided to make the visit to the Caldeira and Capelinhos volcanoes, which had been planned for the next day. Finally we would not visit Caldeira because visibility was so poor.

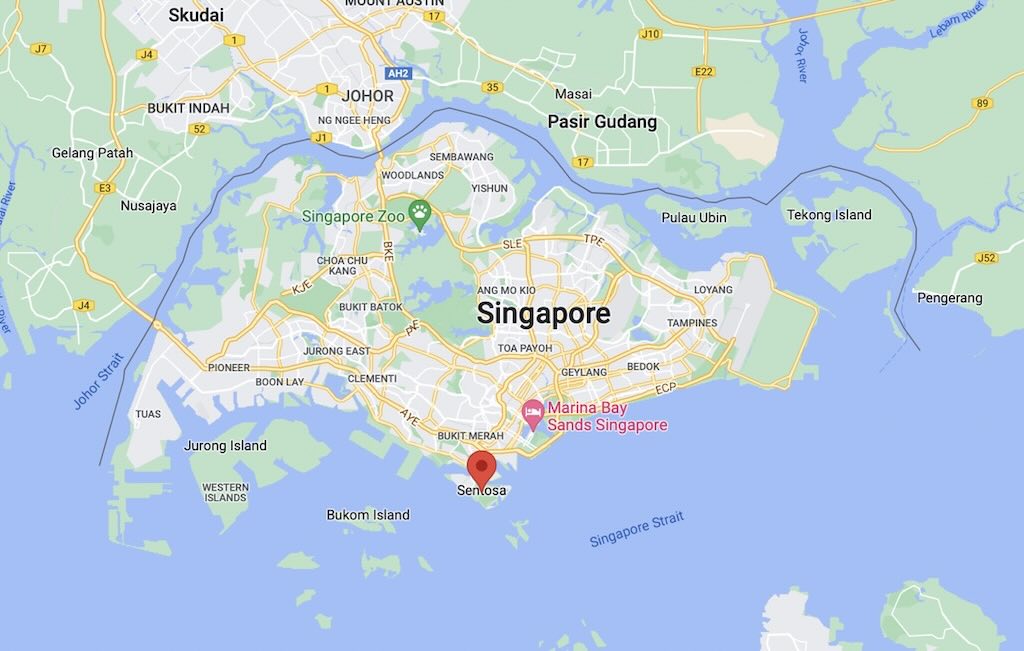

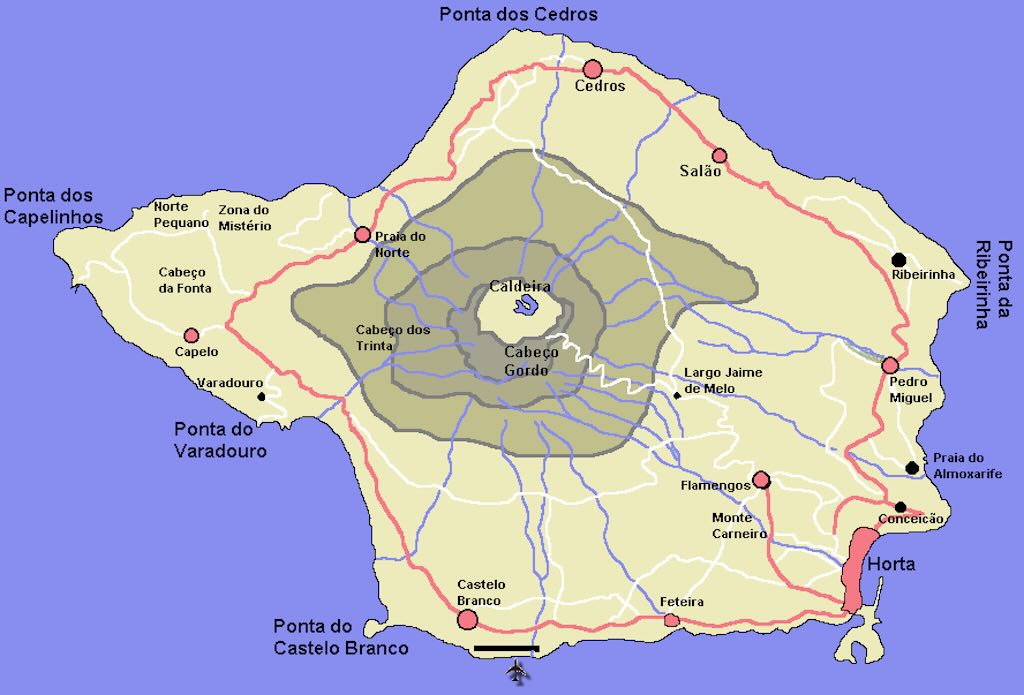

Firstly, we will need a useful map of Faial, not too detailed, but sufficient to position our visit to the island.

So our trip (in a small minivan) started with a visit to Ponta do Varadouro, and the Piscinas Naturais do Varadouro (Varadouro natural swimming pools) which are tidal natural pools set into the striking black basaltic rocks (volcanic rock).

These pools are in the Zona Especial de Conservação da Ponta do Varadouro (Ponta do Varadouro Special Conservation Zone). So its part of the European Union’s Natura 2000 network, aimed at ensuring the long-term survival of Europe’s most valuable and threatened species and habitats, and part of the Faial Nature Park, which encompasses various protected areas on the island to promote biodiversity and sustainable use of natural resources.

We can just see a path going down to the sea, but nearby there are sheltered saltwater pools set in the rock that are certainly safer. In the summer there are restrooms and showers, a bar service and lifeguards.

Very near the pools, in front of the Antigas Termas do Varadouro, we could see a spectacular waterfall nearby (Ribeira des Águas Clares).

In 1868, sulphurous waters with medicinal properties were discovered there, and thermal baths were built, but have now been abandoned.

Our next stop was at the Capelinhos volcano (Vulcão dos Capelinhos). There is a parking, an Interpretation Centre (i.e. a museum), and the abandoned lighthouse (Farol da Ponta dos Capelinhos).

This was the most recent volcanic eruption in the Azores above sea level. The eruption last 13 months, from September 27, 1957 to October 24, 1958.

It started as a Surtseyan eruption (submarine-to-subaerial explosive phase) 300 meters from the coast, and evolved into Strombolian eruption (less violent, lava-spattering). Over time, material accumulation formed a new islet which eventually connected to Faial Island. Later phases included lava flows and cinder cone building.

Originally about 2.4 square-km of new land was added. However some has been eroded, and its possible that in the next 30-50 years the entire area will disappear.

Homes and agricultural lands was buried under ash, and a lighthouse was partially buried (the tower still stands as a landmark). There were no fatalities. As a consequence around 4,000 people left the island, mostly to the United States. This actually influenced US immigration policy (Azorean Refugee Act, 1958).

The Interpretation Centre was designed by Portuguese architect Nuno Ribeiro Lopes. The preliminary study was publicly presented in July 2003, and the Centre opened in August 2008. The building is constructed from exposed reinforced concrete, deliberately left without additional facing to reflect the raw, volcanic environment. The roof is covered with rammed earth, blending the structure seamlessly into the surrounding landscape.

The Centre is built underground, beneath the volcanic ash from the 1957–58 eruption, and visitors enter through a 25-meter-diameter circular foyer (seen above). The structural engineer was a certain Mário Veloso, and the main contractors were a consortium comprising Mota-Engil, S.A., Somague-Ediçor, S.A. (now Sacyr Ediçor, S.A.), and Marques, S.A.

The Centre was nominated for the European Museum of the Year Award in 2012 (won by Medina Azahara Museum near Córdoba). You can see my review of this site “Madinat al-Zahra (Medina Azahara)“.

Below we can see part of the islet formed, an islet that will probably disappear over the next 30-50 years.

The above photo is one I took standing near the old lighthouse. Below are three more professionally taken photos showing the coastal area, and we can better see the impact that the volcano had on the local environment.

We can also just about see the old lighthouse just next to the visitor centre.

After an outstanding picnic in the rain, which included a memorable local cheese with a fantastic tomato jam, we moved on to visit the cultural landmark Porto da Fajã.

As seen below, this was a modest harbour originally used by local fishermen, but it is now a popular site for swimming, though unsupervised. Nearby there were once some vines and rustic adegas (wine cellars), now mostly abandoned. The term fajã describes coastal land formed by volcanic debris and lava flows.

The weather did not offer many alternatives, so we decided to visit Fábrica da Baleia de Porto Pim (Porto Pim Whaling Factory).

This was a fully operation whaling factory built in 1941 and owned by SIMAL – Sociedade Industrial Marítima Açoreana, Lda. It actually operated during WWII and beyond, using steam-powered autoclaves and equipment from Norway and Germany. Over ~30 years (1942–1974/75), it processed 1,940 sperm whales, producing roughly 44,000 barrels of oil.

However, it ceased operations in 1974, following the global decline in whaling. In 1980 it was purchased by the Regional Government and designated “Property of Public Interest” in 1984. Initially it was restored and inaugurated as the Centro do Mar in 2000, then in 2004 became part of the Observatório do Mar dos Açores (OMA). In 2010, it was integrated into Monte da Guia Natural Park. A second renovation occurred in 2018, which included a 10-metre female sperm whale skeleton.

The day concluded with another talk by marine biologist Russell Arnott. This time the focus was on whales and dolphins.

15 May 2025 (Day 3) - "Behind-the-Scenes"

Originally planned as Day 2, “Behind-the-Scenes” involved meeting the researchers and biologists from the universities of Lisbon and the Azores. They act through the Naturalist – Science & Tourism.

This is a team of marine and terrestrial researchers and field biologists affiliated with the University of Lisbon and the University of the Azores, with over a decade of experience working on Faial and Pico. They operate as a MARE startup (Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre, University of Lisbon), blending tourism with research-based activities. What this means is that every whale-watching, birding or hiking tour is conducted by researchers actively collecting scientific field data. They constantly monitor cetaceans, bats, sharks, seabirds, flora, and the local geology. They also collaborate with the Department of Oceanography and Fisheries (DOP/UAç) in Horta, a major institute studying marine ecology, oceanography, seabird and cetacean ecology. Finally, they contribute 10% of tour revenues to the NGO AtlanticNaturalist.org, which supports conservation projects.

Our day started with a discussion about spotting whales, dolphins, turtles and birds. They described in general terms about global conservation efforts and how data was shared.

It was constantly mentioned that the duration of the time at sea depended on where the marine species were to be found on the day and the weather forecast. On each day, the aim was for two three-hour expeditions aboard zodiac boats.

Generally, despite May being considered one of the best months, our week was not blessed with particularly good weather.

May is part of the spring migration, when blue whales, fin whales, and sei whales pass near the Azores. However, migration patterns are variable, and the exact timing can shift year to year. Some species may already have passed or not yet arrived, depending on oceanographic conditions.

For clarity the blue whale is named for its bluish-gray coloration, especially striking underwater where the light enhances its blue hue. The fin whale is named for the prominent dorsal fin located far back on its body, distinguishing it from other large whales. And the sei whale is named after the Norwegian word sejhval, because it often appeared off the Norwegian coast at the same time as the sei fish (pollock).

All three species, blue, fin, and sei whales, are long-distance migratory baleen whales. They migrate from low-latitude wintering areas (likely in the tropical or subtropical Atlantic) to high-latitude summer feeding grounds in the North Atlantic (such as Iceland, Greenland, or Norwegian waters). The Azores archipelago sits in a prime location along their northbound migratory corridor. And Spring is the peak time for sightings, especially March through May, with May often showing the highest activity. So the Azores serve as an important spring feeding stopover, especially due to the seasonal zooplankton and krill blooms in the region.

This contrasts with species like the sperm whale, which is resident in the Azores and can be seen throughout the year. So the Azores has a dual role as both a migratory waypoint and a long-term habitat.

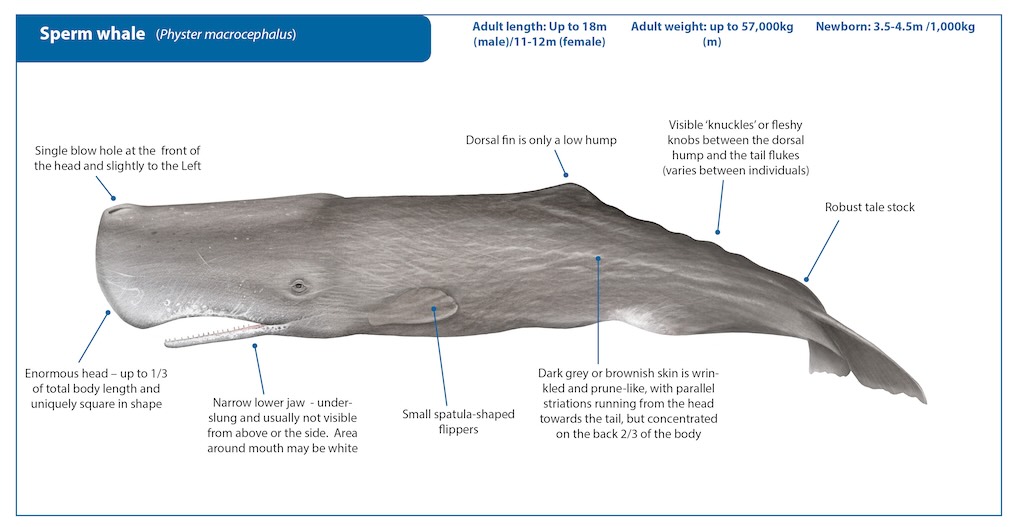

Sperm whales are called so because early whalers mistook the waxy substance in their heads, spermaceti, for whale semen. They are also different from baleen whales in that they are toothed whales, and in fact are the world’s largest toothed predator.

The reality is that the whales are in open ocean, not confined to coastal areas of the islands. The Atlantic weather is unpredictable (as we will learn during our stay), and May can bring sudden changes in wind and waves. Swells and chop (short, irregular, and often steep waves caused by local winds) may limit visibility and affect the comfort and safety of boat trips. Even with experienced operators, spotting is not guaranteed due to the sheer size of the search area.

For example, the planning was for a trip out yesterday, but was postponed due to rough seas and poor visibility. The simple fact is that windy conditions make spotting the ‘spout’ harder, i.e. the visible column of mist or spray exhaled by a whale when it surfaces to breathe.

In short, May is a good month biologically, but logistics, sea conditions, and timing variability make sightings uncertain.

So the next step was to tog-up and get out to sea in a zodiac. First we were provided with what are called bib overalls (also called bib-and-brace or dungarees). These were wind and waterproof, but not insulated (the French word salopettes is also often used for these wind-and-waterproof trousers). Then came an over-jacket, and a life-vest.

Above we can see that the zodiacs used could seat 8-10 people, whereas in the feature image we can see larger zodiacs are often used. Most whale watching tours provide half- or full-day trips for larger groups doing walking or trekking tours on the islands.

We can see the ‘pod’ of six ‘watchers’, the group guide (Armando), the group specialist (Russell), and the driver. But the most important person was behind the camera, the specialist from Naturalist.

We all spent a lot of time taking, or more correctly trying to take, photos. All were meant to be whales, dolphins or birds, but almost all turned out to be just photos of water and sky.

However, we also have the photos taken by our specialist from Naturalist. She somehow managed to “capture the moment”. The photos are/were on their website, but I don’t know how long they remain there, so I’ve copied some into this blog posting.

The commentary from Naturalist was…

Today we encountered a pod of sperm whales with curious juveniles spy-hopping to get a look at us — an unforgettable moment as they approached the boat! 🐳💙

To top it off, a massive male sperm whale surfaced nearby after a 1-hour deep dive, briefly resting at the surface before lifting his tail and diving back down to hunt squid in the deep.

Spy-hopping is a behaviour observed in marine animals, especially whales, dolphins, and sometimes sharks, where the animal vertically pokes its head out of the water, often slowly and deliberately, as if to “look” around above the surface.

One of the challenges for a neophyte whale watcher is to try to understand how an expert identifies one type of whale from another.

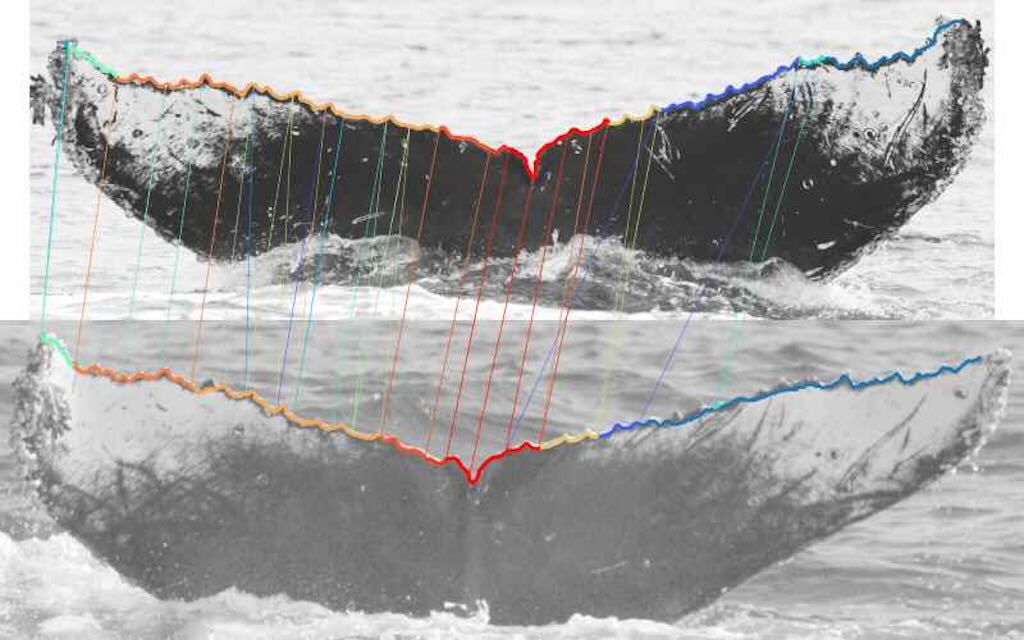

The first characteristic is that sperm whales have a single, left-facing blowhole. Their spout (blow) is angled forward and to the left, so very different from the vertical twin spouts of baleen whales. Next sperm whales have an enormous, block-shaped head, about one-third of their body length (remember the sperm whale we saw in the museum). Also, unlike most whales, sperm whales have a low, rounded dorsal hump, followed by a series of knuckles or ridges down the spine. Each sperm whale emits unique patterns of echolocation clicks (called codas). Finally sperm whales have a unique ID, namely the nicks, notches, scars, and shape variations on the trailing edge of the fluke. The outline of the fluke is as individual as a fingerprint, and there exists an ID catalogue/database (e.g. flukebook).

The word “fluke” comes from Old English floc, meaning the lobe of an anchor or flatfish. So it refers to a flat, broad shape, and the term was extended to whales because the tail resembles a bi-lobed anchor fluke.

A whale’s tail fluke is used for propulsion through vertical movements. Unlike fish, which move tails side-to-side, whales use up-and-down strokes to swim efficiently. The tail is composed of dense connective tissue (rich in collagen fibres), not bone or muscles, and is covered in tough, smooth skin. It’s the main way whales swim and dive.

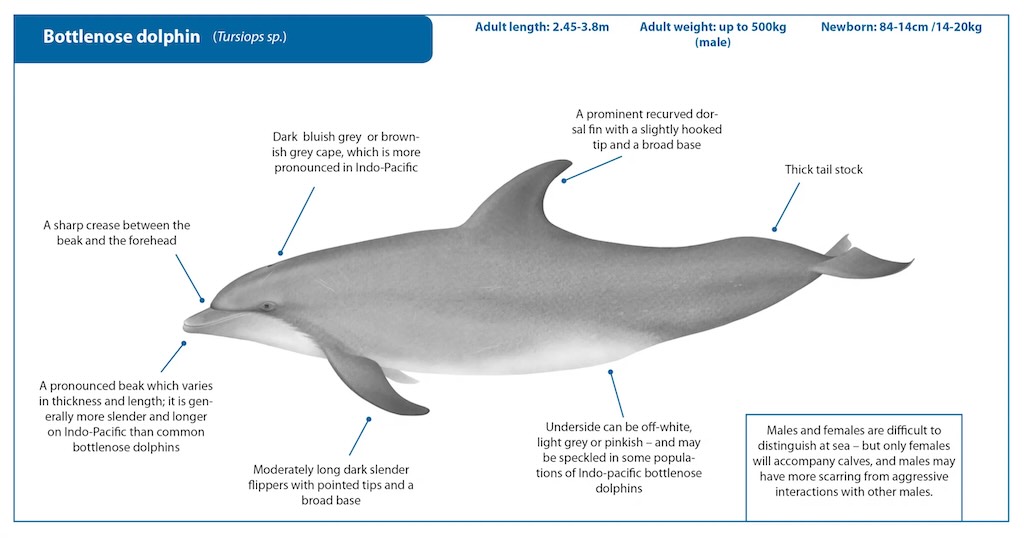

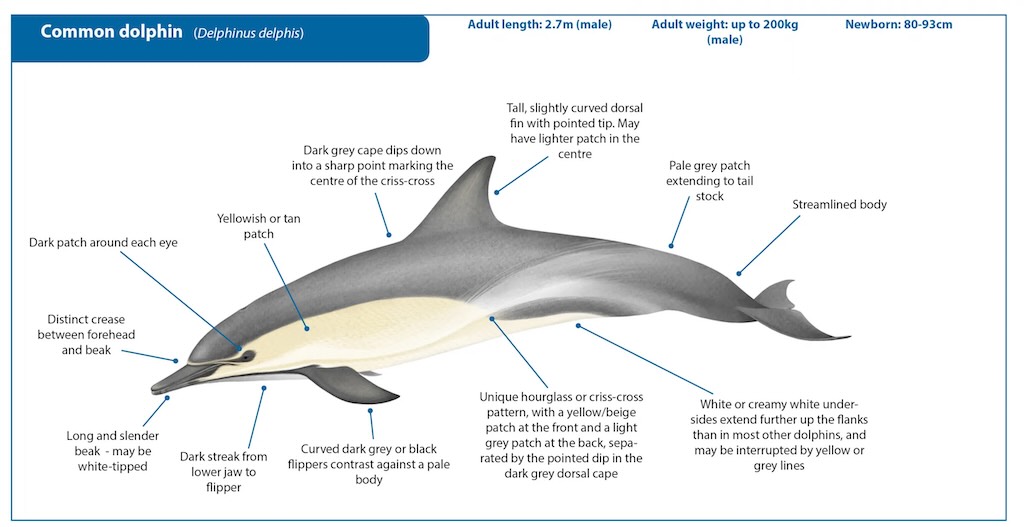

Above we have the bottlenose dolphin. There are ~38 species of oceanic dolphins (Delphinidae), and there are four resident dolphins in the Azores, namely, the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), the common dolphin (Delphinus delphis), Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus), and the Atlantic spotted dolphin (Stenella frontalis). There exist also 4 species of river dolphins and 7 species of porpoises.

A bottlenose dolphin has a short, thick “bottlenose” beak. It also has a curved dorsal fin that is tall, hooked, and located mid-back. And finally it has a grey colour, darker on top, lighter underneath. They are easy to spot due to their size (up to 4 meters) and active behaviour around a boat.

The name “bottlenose” comes from the shape of its snout, which resembles the neck of a bottle. The term was probably coined by English-speaking naturalists in the 18th or early 19th century, though there is no single documented individual who definitively invented the common name.

“Beak” comes from the Old French bec, from Latin beccus, meaning a bird’s bill. In biology, it’s often used descriptively for similar structures in non-bird species, not because they’re homologous, but simply because they look like beaks.

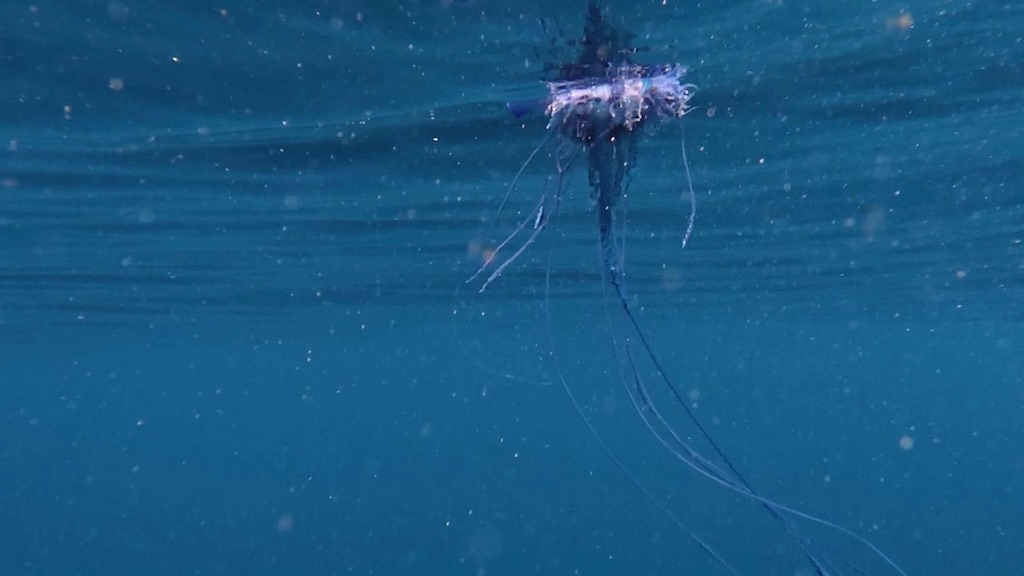

We also saw a Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis). Although it superficially resembles a jellyfish it’s a different species. The name comes from the fact that it resembles the Portuguese caravel at full sail. It is not a single animal but a colonial organism made up of specialised individuals (called zooids) that function together as one. I was surprised how small it was, it was only about 15 cm long in the water, but it had very long tentacles underwater. You could easily see why a child might want to touch it.

In the evening, I did not participate in a visit to see the largest colony of Cory’s Shearwater (Calonectris borealis) in Faial. From late spring to late summer, 80% of the world’s population of Cory’s Shearwater nest in the Azores.

For those who went to see the birds, it rained and they also enjoyed a memorable display of thunder and lightning.

16 May 2025 (Day 4) - Exploring Pico

Again the weather was not on our side, so we decided to explore Pico. Above we can see the stratovolcano Ponta do Pico, which is the highest mountain in Portugal, the Azores, and the highest elevation of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (2351 m). Pico is also in fact the second largest and, geologically speaking, the most recently formed island of the Azores, being around 300,000 years old.

As you might guess, the above photo was not taken on the 16 May, but on 17 May, and is the view from our hotel.

Originally we intended to take the 30-minute ferry ride to Madalena, the town on Pico more or less in front of Horta. However, it was easier to simply kit-up and take the zodiac.

If we look carefully at the satellite photo below we can see on the left two small rocks sitting in the sea just in front of the town of Madalena. The landmass in the upper right-hand corner is the island of São Jorge, just a few kilometres away.

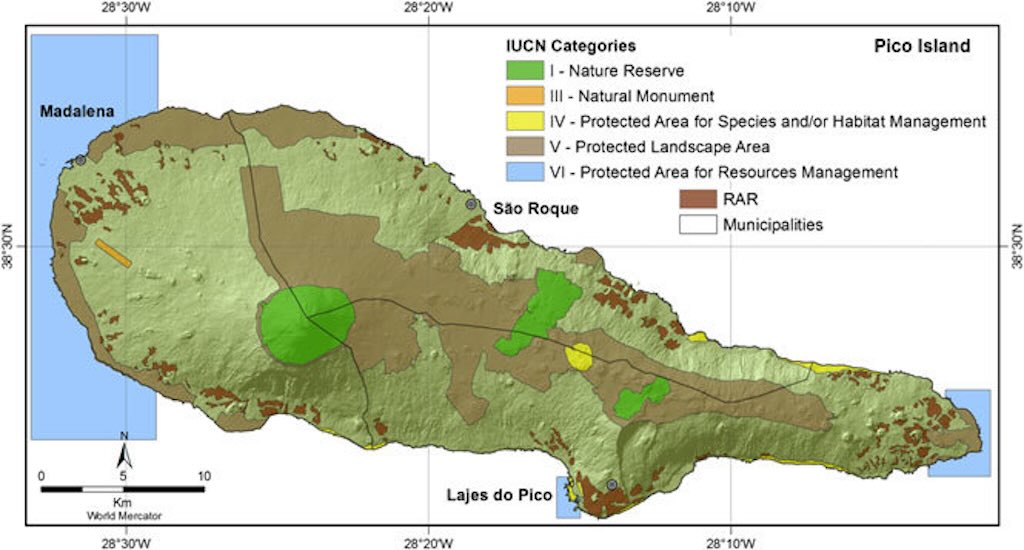

Pico is in fact the second-largest island in the Azores archipelago with an area of approximately 447 square-km, but has a population of only around 13,000. The island’s landscape includes lava fields, volcanic caves, and a rugged coastline. Its economy is traditionally based on fishing, agriculture (especially vineyards), and increasingly tourism (with an emphasis on hiking, volcano tours, and viticulture).

The lighter and darker greens help us understand better the local environment on the island. The variation in green tones does not consistently correspond to a simple distinction between native (original) plants and invasive species. However, there are some tendencies worth noting:-

- Original vegetation on Pico, before human settlement, was dominated by subtropical laurel forest (laurisilva) and other Macaronesian native species, many of which have a lighter, brighter green tone (e.g. Erica azorica, Laurus azorica, Ilex perado).

- Large areas today are covered in pastures and exotic tree plantations, particularly of Cryptomeria japonica (Japanese cedar), which has a dark green hue and is non-native but widely planted.

- Invasive species like Pittosporum undulatum (Australian cheesewood) and Hedychium gardnerianum (wild ginger) tend to have darker, waxier foliage, and they dominate some mid-elevation and disturbed forest zones.

- Lighter greens often indicate pastures, grasslands, or low native shrubs, especially at lower elevations or on cultivated land. These are often not original ecosystems but may include some native species or traditional agriculture.

- Darker greens often show dense forested zones, many of which are not original laurisilva, but exotic or invasive species, especially Cryptomeria conifer plantations and Pittosporum thickets.

Light vs. dark green is not a particularly reliable visual guide to native vs. invasive species. But in general darker forest zones are often non-native trees or invasives, whereas paler greens point to pastures, agriculture, or native scrub.

Pico Island has made significant and well-structured efforts to protect its natural environment, and over one-third of the island is under some form of protection.

The island includes a network of protected areas under the Azores’ Regional Network of Protected Areas (Rede de Áreas Protegidas dos Açores). This includes the Mount Pico Natural Reserve, established in 1972, and the Natural Park of Pico Island, created in 2008. This includes Gruta das Torres, the longest lava tube in Portugal, and the Mistérios of São João (1718) and Silveira (1720), which are historic lava flows with unique habitats. The local population named them “mistérios” (mysteries), because they saw “rivers of fire” (rios de fogo) coming out of the earth for no apparent reason, destroying their belongings.

We visited Lagoa do Capitão, located on the central plateau of Pico at 826 meters above sea level. This is one of the island’s largest freshwater lakes. It is a priority habitat under the EU’s Natura 2000 network, and is one of the few places on Pico where freshwater, altitude, and volcanic terrain combine to create a unique Azorean landscape.

“Lagoa” refers to a small lake or lagoon, often formed in volcanic craters or depressions.

The windswept tree-line around Lagoa do Capitão is characterised more by low, stunted vegetation than by a classic forest tree-line. This is due to a combination of altitude, strong Atlantic winds, acidic volcanic soils, and frequent fog and rain. This creates a kind of harsh, subalpine environment often called a krummholz-like zone (a German term for “crooked wood”).

What we see above is Juniperus brevifolia (Azorean juniper), an endemic conifer, often low-growing and gnarled at this elevation.

We also visited Lagoa do Caiado, which is the largest lake on Pico. Situated at an elevation of approximately 822 meters on the Achada Plateau. The lake is renowned for its pristine natural environment, largely untouched by invasive species. Since 1993, the lake’s waters have been used by the São Roque do Pico Town Council. The area around Lagoa do Caiado is a haven for birdwatchers, and also offers panoramic views over the island (not I might add during our visit).

Landing in Madalena, our first visit was to see the local vineyards. The above photo was taken near Madalena, in the civic parish of Criação Velha. This was an area where cattle were raised. Criação means “raising”, and Velha is old.

Viticulture on Pico began in the late 15th century, shortly after the island’s settlement. Early settlers, recognising the potential of the volcanic soil, introduced grapevines, particularly the Verdelho variety (often associated with the island of Madeira). To combat the island’s challenging climate, characterised by strong Atlantic winds and salty sea spray, farmers constructed thousands of small, rectangular plots known as currais, enclosed by dry-stone basalt walls. These structures not only protect the vines but also retain heat, aiding grape maturation. In Spain Verdelho is grown under the synonym Verdello (which is not the same as the Italian grape Verdello).

In earlier time the wines were exported to mainland Europe. It’s often mentioned that they were found in the cellars of Czar Nicholas II. Later the variety was all but wiped out in by powdery mildew and the phylloxera plague. Returning to their roots, the islands of the Azores have been planting the grape again. The focus remains on indigenous grape varieties like Verdelho, Arinto, and Terrantez, cultivated in the historic currais.

In 2004, the “Landscape of the Pico Island Vineyard Culture” was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This recognition underscores the area’s exceptional testimony to a unique viticultural tradition, characterised by its distinctive stone-walled currais, traditional manor houses, wine cellars, and the integration of agricultural practices with the natural environment.

In the 19th century, Pico Island boasted up to 15,000 hectares of vineyards, but today approximately 250 hectares are actively cultivated. A leading winemaker on the island, currently produces around 150,000 bottles per year, so total production on the island is probably in the range 250,000 to 300,000 bottles per year.

That’s around 150 metric tonnes of empty glass bottles to be imported each year (representing about 15 to 35 containers, depending on size).

The currais (plots) can be as small as a few square meters. Each plot has a cadastral number and owner, registered officially. However, in practice, local farmers and families know who owns which currais. This knowledge is often passed orally, within families or among long-standing community members. And inherited vineyards may be worked by multiple family members who own adjacent or even interspersed plots. So the result is that a single vineyard area may contain dozens or even hundreds of owners. Some farmers rent or co-manage plots informally or via a co-operative.

Before leaving the island we had a tasting of local Pico wines, with Lucus Amaral, the islands youngest producer. Check out these reviews, review 1, review 2, and review 3.

17 May 2025 (Day 5) - Whale Watching

We were back out on the water, and Naturalist reported…

What a spectacular day at sea! 🌊 We were treated to sightings of our resident sperm whales, playful dolphins, and even a humpback whale foraging alongside common dolphins and elegant Cory’s shearwaters. Nature never ceases to amaze!

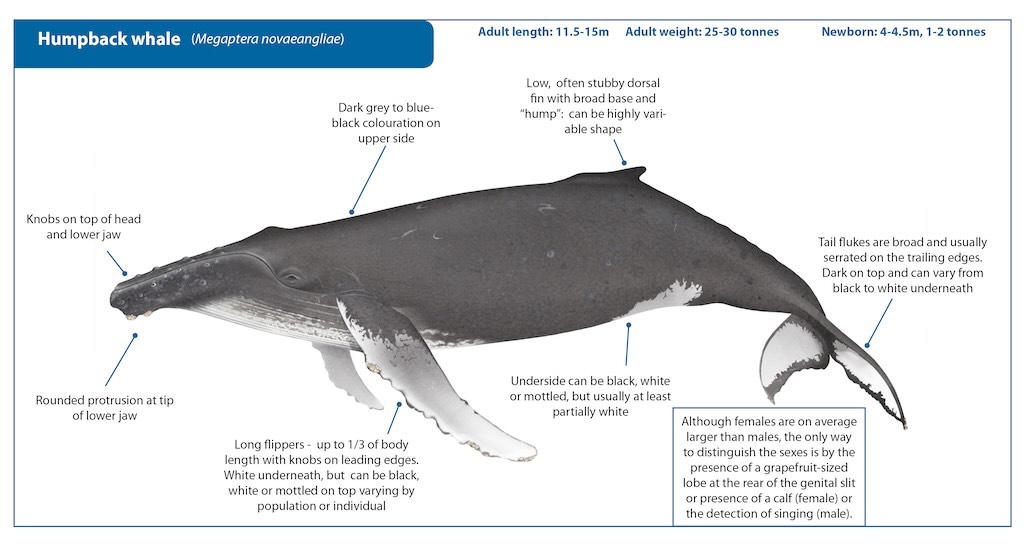

The humpback whale has a massive, stocky body, and can measure up to 16 meters in length. It has a small, knobbly dorsal fin set far back, and long pectoral fins (up to one-third of body length). It also has a knobby head and lower jaw (with tubercles). When diving, it often shows its broad, notched tail flukes.

In the open ocean, it slaps its fins or tail, and arches its back just before a deep dive. It’s this “hump” that gives this whale its name.

The tubercles opens up an interesting sub-topic. The knobby bumps found on the leading edge of a humpback whale’s pectoral fins (flippers) and on the head and jawline, each contains a single hair follicle (called a vibrissa). They are believed to help sense water movement. The rounded protrusions are filled with dense connective tissue (not bone), and are structurally raised above the surrounding surface.

However, the tubercles on the fins and on the head and jawline are different, and serve a different purpose.

Each tubercle on the flipper contains a single hair follicle, but not a hair. Firstly, it is thought that tubercles channel water into streams, reducing flow separation and turbulence. This allows humpbacks to maintain lift at higher angles of attack, so they can tilt their fins more steeply without stalling (losing lift). What this means is that the whale can make sharper turns and is more agile, ideal for bubble-net feeding and quick prey capture.

So the pectoral fin tubercles are entirely structural. They improve water flow and manoeuvrability but have no sensory hairs.

The presence of hairs (vibrissae) on the upper and lower jaw, suggests a tactile sensory function. Which appears to be quite unusual and rare among large cetaceans. The vibrissae are stiff, bristle-like sensory hairs embedded in follicles. They are found one per cranial tubercle, particularly along the upper jaw (rostrum), chin, and occasionally lower jaw. In adult whales, they are short and can be hard to see, but the follicles remain functional. The vibrissae are innervated, meaning each follicle is connected to nerves that relay tactile information to the brain. The follicle is embedded in richly vascularised and innervated skin, similar to the whiskers of seals or cats. They are mechanoreceptors tuned to sense water movement or vibrations, and contact with objects or prey. It’s also possibly that they can provide chemical cues in turbulent flow.

All mammals evolved from ancestors with facial vibrissae. Many toothed whales (odontocetes) lose them shortly after birth, whereas baleen whales (mysticetes) like humpbacks retain these cranial vibrissae throughout life. This suggests a selective advantage, probably linked to tactile feedback during feeding. It’s suggested that feedback from these hairs may assist in the timing and angle of mouth-opening feed in complex, three-dimensional environments, often with limited visibility.

Another feature seen in the above photo is next to the whale. What is the light-blue patch in the water?. As whales swim, surface, or dive, they disturb the water with immense force creating turbulent flow which entrains air, forming microbubbles that reflect more light, making the water appear milky or pale. Especially visible when whales breach, tail-slap, or fluke dive. They are sometimes known as “fluke print”, a smooth, light patch left when a whale moves just below the surface.

The common dolphin is a fast, social, and highly recognisable oceanic dolphin known for its colourful pattern, hourglass shape on the sides, and acrobatic behavior.

There are two main species, the Delphinus delphis (short-beaked) and the Delphinus capensis (long-beaked). We can see that it has a distinctive yellowish-tan and grey hourglass shape on the sides. Its beak is long and narrow, with many sharp teeth. The dorsal fin is tall, curved, often dark with a lighter patch beneath. They are quite small 2.0–2.7 metres long, and weigh up to 150 kg. It was once considered the most widespread and abundant dolphin species in the world, hence “common”.

Today, it is thought that the short-beaked Common Dolphin (Delphinus delphis) is in fact the most numerous dolphin species by individual count. However, it is also thought that the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) is the most adaptable in that it is found in all temperate and tropical oceans worldwide, from coastal shallows to deep offshore waters.

Risso’s Dolphin (Grampus griseus) is a medium-large dolphin, that can reach 4 meters long and 500 kg. It has a rounded forehead with no beak, which is unusual for dolphins. Its dorsal fin is sickle-shaped and one of the tallest among dolphins. It is born dark gray to black, but adults become pale grey to white, often heavily covered in white scars. The scars are caused by intra-specific interactions (teeth raking) and possibly squid prey. The interactions can be competitive (e.g. for food, or over mates or hierarchy). But it can also be from social dominance displays, aggressive play, or simple territorial assertion (in males). Named after Antoine Risso, a 19th-century French naturalist. But also sometimes called the grampus, an older name historically confused with orcas.

The degree of scaring acts like a living biography. It maps age and experience, hints at dietary specialisation, and aids in long-term tracking. Scientists use it for photo-identification, tracking individuals over time, similar to using fluke patterns in humpbacks.

The different drawings of whales and dolphins on this post come from the International Whaling Commission (IWC). However they don’t currently provide a dedicated illustration of the Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus), possible because they are currently classified as “Least Concern” by the IUCN.

18 May 2025 (Day 6) - Whale Watching

We started the morning trying to find what had been spotted by the lookouts, but failed. We came back wet.

However, later in the afternoon the weather cleared up, and everyone was called back for a last zodiac trip (to which I did not participate).

Naturalist finally reported…

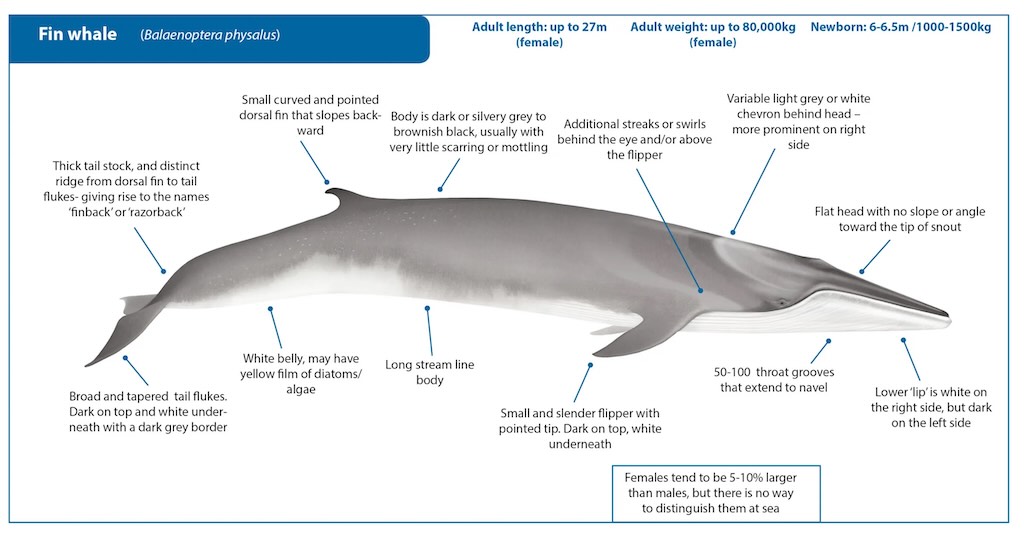

Patience pays off! We went out later than usually to the sea and encountered three Fin whales in the same area!!! Also bottlenose dolphins to finish well the day!

The fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) is the second-largest animal on Earth (the largest is the blue whale Balaenoptera musculus). A fin whale has a streamlined, torpedo-shaped body, built for speed. It can measure up to 27 metres long, and its blow is columnar and can rise up to 6 metres high. It has asymmetrical head colouring, with a dark left lower jaw and a white right lower jaw, quite a unique diagnostic trait. Its dorsal fin is small, hooked, and located far back on the body.

Known as the “greyhound of the sea”, it can reach speeds of up to 40 km/h in short bursts.

It filter-feeds on krill, small fish, and zooplankton, by lunge feeding. It accelerates toward prey, opens its mouth wide, and engulfs massive volumes of water and prey. It has 50–100 baleen plates on each side of the upper jaw. These are made of keratin (same material as human fingernails and hair), hang from the upper jaw, and the inner edges are fringed with fine bristles or hairs. The whale closes its mouth and uses its tongue to push the water out through the baleen. The prey is trapped on the inner bristled edges of the baleen plates, and then swallows.

Dorsal fins on whales and dolphins appear to come in different shapes, sizes, and positions. Clearly the dorsal fin’s role isn’t rigidly fixed like a limb or tail. So what do dorsal fins actually do?

They primarily serve hydrodynamic and thermoregulatory functions:-

Stability during swimming

- The dorsal fin acts like the keel on a boat. Ut helps the animal swim straight and prevents rolling or yawing (side-to-side movement).

- This is especially important for fast swimmers like dolphins and orcas, which make quick turns and accelerations.

Thermoregulation (body temperature control)

- The dorsal fin is full of blood vessels and lacks insulating blubber.

- It acts as a radiator, releasing excess heat generated by swimming, especially in warmer waters or during intense activity.

Returning early in the morning outing, we decided to go and visit one of the “vigias” (lookouts). I’m not sure, but I think this is quite unusual.

The whale watching groups on Faial and Pico, collectively fund five lookouts (two in Faial and three in Pico). These are small white lookout huts strategically placed on elevated cliffs around the island’s coastline. The locations offer sweeping 180º to 360º views of the Atlantic Ocean, allowing spotters to detect the tell-tale signs of whales (blows, breaches, dorsal fins). On Faial, several of these huts remain operational, including at Vigia da Ponta da Espalamaca (near Horta), and Capelinhos area, among others.

The equipment is rudimentary, binoculars and a VHF radio link to the different whale watching groups. The real skill is in the vigias’ experience, trained eyes, and knowledge of local waters and whale behaviour. They look for blows (spouts of vapour), colour or movement patterns on the water’s surface, breaches or tails. They then guide the different boats by relative compass bearing from known landmarks, estimated distance from shore, and species identification (if possible), based on behaviour and blows.

If they can, they update the position dynamically, as whales can change direction or dive for extended periods. By comparing angles and positions, they can triangulate the whale’s location more precisely. This method is particularly useful for tracking fast-moving or deep-diving species like sperm whales.

We could see that the location was not particularly comfortable, the work quite challenging, and so, clearly needs people with a special talent for spotting whales at up to 10 km away. Hour-after-hour, day-after-day.

19 May 2025 (Day 7) - Transfer to Horta airport

This should have been a decidedly uneventful day. All we had to do was leave the hotel before 12:00 and take the 16:45 flight to Lisbon, transfer hotel-airport was included.

However, we were messaged to tell us that our flight was delayed to 19:45. In the airport we were then informed that our plane had been diverted to another island, but was still expected. Everyone saw, using the usual tracker apps, that the plane did circle nearby, before flying off, leaving everyone stranded. Everyone knew what would happen before it was officially announced. The usual mess occurred, only slightly alleviated by the fact that its was a small airport, and the staff were very honest and reasonable.

We (the remaining members of the “pod”) queued to rebook tickets, collect taxi vouchers, and be told that all the hotels were fully booked. We also received a detailed description of what we could claim back, and how to do that. This was not helped by the fact that each had follow-on flights to rebook, and pick-up’s and hotels in Lisbon to cancel and rebook. We also had to collect our bags.

The true challenge was to find a hotel/accommodation. Nothing to be found on the usual apps. The ladies had started talking to a group/family of four Portuguese women that were in the same situation. Worse in that their flight from Pico had been cancelled the night before, and they had moved to Faial in the vain hope of leaving for Lisbon the next day.

Anyway, after some failed attempts at finding a hotel, two workers in the airport came forward and suggested an apartment option. Now we were eight people, so it obviously involving a bit of sharing, etc.

It turned out to be a modern refurbished house back in Horta. I think, but am not sure, that it had been renovated by the architect daughter of one of the airport workers. In any case it was a fantastic find, well beyond our dwindling expectations.

BALA DAS CALDEIRINHAS +351912208062

Just for clarity, at the airport desk I received a new boarding card for the flight on 20 May, and two taxi vouchers (outbound/return), valid 72 hours, and instructions for reimbursement.

Accommodation would be refunded for up to €80, meal (lunch or dinner) up to €15, and breakfast or light snack up to €7.

The invoice must be made out to SATA International – Azores Airlines, with the taxpayer number 512029393.

Then they needed to be submitted using the claim form to www.azoresairlines.pt/en/support/contact-us.

20 May 2025 (Day 8) - Horta airport (again)

Boarding was planned for later afternoon on the 20 May. We all managed to get back to the airport, check in luggage, and actually board the plane. Things were looking up! Our plane had landed, the weather looked fine, we were sitting in our seats, seatbelts attached. When they announced that the departure had been cancelled.

I’m not sure where the message/rumour came from, but it was said that we would arrive too late in Lisbon.

So we all had to disembark. This time we kept our old boarding passes (we had to collect new one the next morning), and our luggage stayed on the plane. We were again given a taxi voucher, but there was also a bus to the town and even a dinner in a local restaurant had been organised (max €15 per person). We were all very lucky to again be able to return to the house from the previous night.

21 May 2025 (Day 9) - Horta airport (again)

This time, wakeup was at 08:00 and take-off was at 09:46, arriving in Lisbon at 13:04.

See my review “Flying – Azores Airlines and Horta Airport, Faial“.

I don’t think anyone is planning to return to the Azores, or Faial, or fly with Azores Airlines, anytime soon.