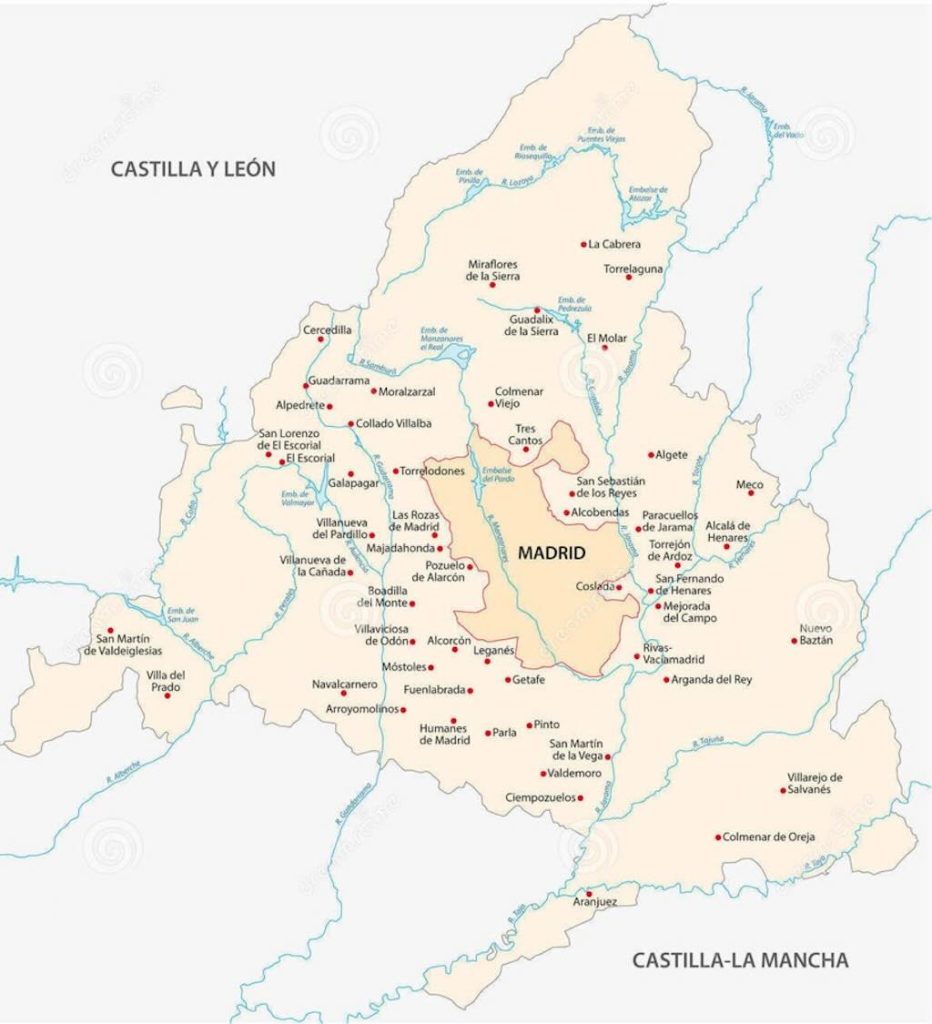

During our second visit to Madrid we decided to also visit El Palacio Real de Aranjuez, in the city of Aranjuez, about 40 kilometres south of Madrid. In fact Aranjuez is actually part of Madrid, in that it is one of twenty judicial districts (partidos judiciales) of the Community of Madrid. It is also one of the larger municipalities in Madrid.

I must admit that my wife and I have listened a multitude of times to the melancholic Concierto de Aranjuez of Joaquín Rodrigo, without ever imagining that there was a place called Aranjuez and that Felipe II (1527-1598) would use it as one of his four seats of government.

And we had no idea that people would call Aranjuez, the ‘Oasis de Castilla‘ in that it is a “jewel saved from the tide of cement and skyscrapers“.

A friend once gave me a book entitled “The Bridle Roads of Spain” by George John Cayley (1826-1878). In it, the author, who they say “often adopted native dress“, described Aranjuez in the 1850’s as a “picturesque, gay tea-garden-looking town, full of brick and stucco colonnades and gingerbread triumphal arches, and avenues of really fine trees, and glittering fountains, and bridges and waterfalls, and flowers and statues and columns, altogether making a brilliant though somewhat French and artificial ‘ensemble’“. He left it with the passing comment that it was a “very pleasant place for the Court to lounge through the hot summer months“.

Here we have Cayley trying to recapture the feeling of the Grand Tour when Spain was a country of contrasts, mysteries, adventure, and exoticism. Aranjuez as a seat of the Spanish court, was a city of noble palaces, hotel establishments and diplomatic missions, for a season. And with Aranjuez it was the spring season, which meant a time for leisure, walks, gatherings, private lunches, away from the protocol and political obligations of Madrid.

Reports confirm that the “Court returns to the town during Holy Week. Rise early, ride, bath, very hot but must dress for court then dine, sleep, walk or air, and attend spectacle“, or the “art of living well“.

Paisaje Cultural de Aranjuez

We are no longer in the 1850’s, so we must content ourselves with the 2019 version of the city. The Wikipedia article on Aranjuez is quite extensive but uninspiring, so we have turned to other sources.

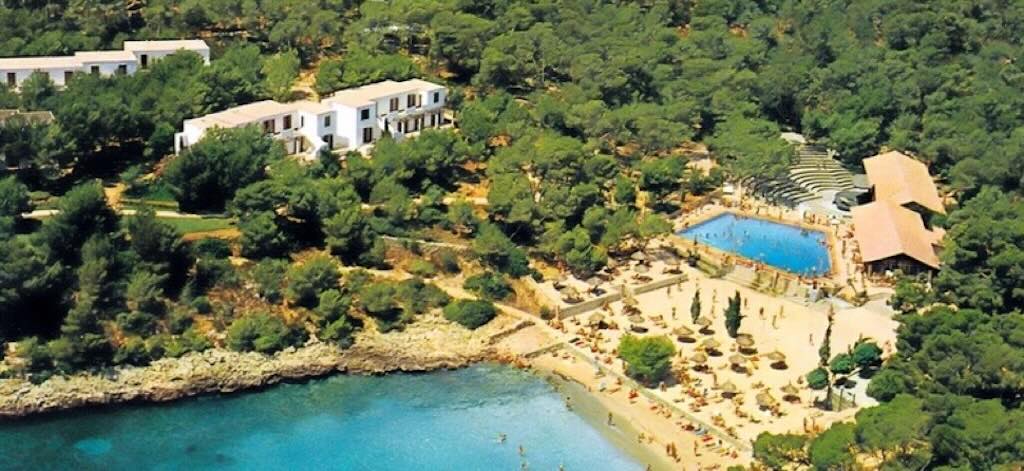

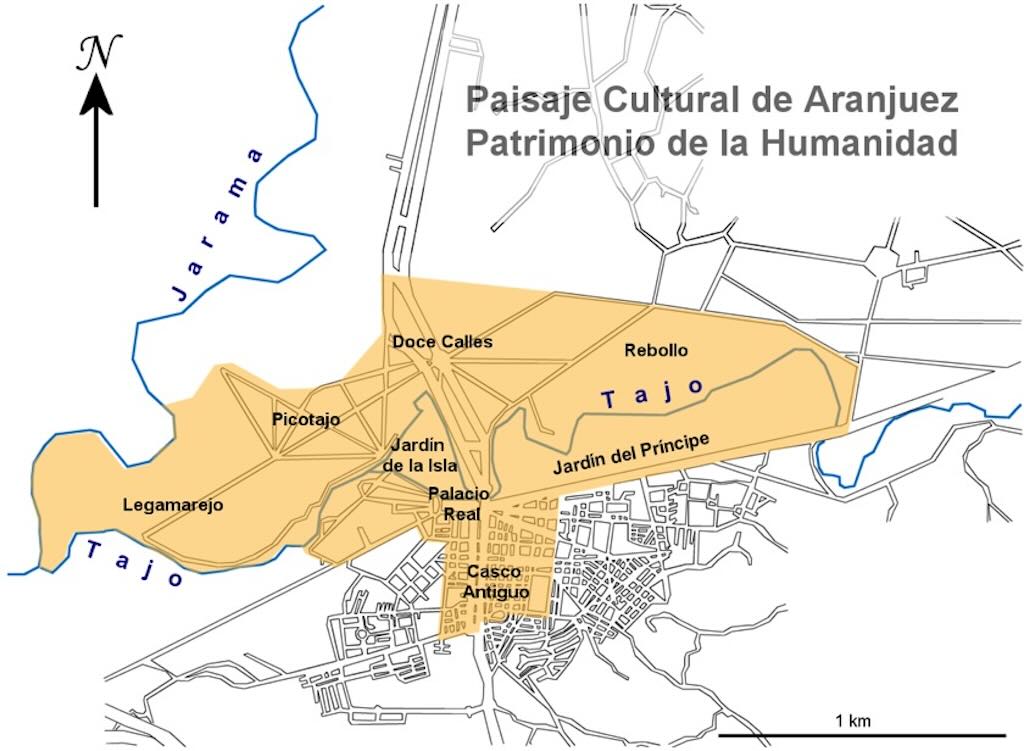

Our visit to Aranjuez was motivated by the idea to visit El Palacio Real, but what we found was that in 2001 the region, and not just the palace, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Landscape. What this did was to highlight the impact the Spanish Crown had on the local landscape, urban and rural life, and the regions forests, agriculture, and architecture.

We have to sit back and remember that 47 Spanish cultural ‘properties’ are included in UNESCO’s World Heritage List, 41 cultural sites, 4 natural sites, and 2 mixed sites (as of 2019). This includes cities (Toledo, Salamanca), archaeological sites (Roman remains of Tárraco), singular buildings (Burgos Cathedral) and natural landscapes (Mont Perdu in the Pyrénées).

However Aranjuez is unique in that it was Spain’s first world heritage landscape. As of 2019 there are only 102 UNESCO world heritage cultural landscapes, and Spain is home to only three of those ‘properties’, i.e. Aranjuez, Tramuntana on Mallorca, and Mont Perdu in the Pyrénées.

So what exactly is inscribed in the World Heritage List? In fact it includes a protected area of just over 20 square kilometres, including a natural space around two rivers, an area of orchards, groves and tree-lined streets, a palace and gardens and the historic centre of a city (casco histórico).

The process leading to the recognition of a site as a World Heritage Landscape is complex, but the idea is simple. It’s a place which combines nature and human intervention. A given natural orography, where its soil, vegetation and rivers are modified and altered by man, to which is added buildings, etc., such as monuments, palaces, and urban areas. All this creates an economy, a way of life, and a culture.

The history of Aranjuez and its relationship with agriculture is a epic story. Remains of Paleolithic, Neolithic and Bronze and Iron Ages have been found. There are also documented references to a population centre in Roman times. Polybius (ca. 264-146 BC) and Livy (64 BC – 17 AD) tell of an important battle won by Hannibal (247-182 BC) very close to the junction of the Tagus and the Jarama.

It is in the middle ages when we find documented evidence for a Villa de Aranjuez. At that time, the Tagus in general and Aranjuez in particular were frontier zones between Christians and Muslims. It was for this reason that Alfonso VIII (1155-1214) had placed it under the control of the Royal Order of Santiago (1171).

If we move into the 20th century, we find Aranjuez almost abandoned, and it was its inclusion in the World Heritage List that saved it. Today the problem is more to do with trying to keep a piece of ‘universal heritage’ alive under the increasing pressure of tourism.

Madrid - capital of Spain

To really understand the historical context of the Palacio Real de Aranjuez we need to understand how Madrid became the capital of Spain. In 1561 it was Felipe II (1527-1598) who decided to bring the capital to Madrid (although for the period 1601-1606 it was moved to Valladolid).

Historians have provided us with a whole list of reasons why Felipe II decided on Madrid. It was in 1405 that Enrique III (1379-1406) built a Casa Real on Monte de El Prado and made the area one of his favourite hunting grounds. This encouraged many local noble families to buy land nearby. One of those families, the Casa de Vargas, built in 1519 a country residence, although many reports prefer to call the residence a palacio. Carlos V (1500-1558) is known to have spent some seasons there. François Ier of France was held captive there between 1525-1526, and upon his return to France it is said that he built a residence in the Bois de Boulogne inspired by the architecture of the Casa de Campo in Madrid (it would become known as the Castillo de Madrid).

In 1552 Felipe II started to annex lands around the Casa de Campo, and in 1562 he purchased the entire estate from the family Vargas. He ordered the building of gardens, ornate grottos and ponds, etc., which later led to the creation of a Real Sitio (Royal residence). Sources also mentioned that some lands had also been expropriated by the Crown after the revolt of the Comuneros (1520-1521), and the monarchy had added them to their hunting grounds.

An interesting additional view is that the great noble Spain families did not have estates near to the Royal residence. In this way Felipe II made sure that no one could ‘cast a shadow‘ over his residence, and everyone would be obliged to be courtier at his court (a similar logic has been attributed to Louis XIV when he moved to Versailles).

There were some ‘royal’ practicalities as well. Madrid was home to Real Alcázar de Madrid, a comfortable palace-fortress. Madrid was close to El Escorial, another palace started in 1563 and finished in 1584. One text mentions that another reason for picking Madrid was that it was not a religious capital and did not have a bishop. This may be linked to the fact that Felipe II saw himself as a champion of Catholicism and the Counter-Reformation, and this was another way to reinforce his authority over Toledo (the archbishops of Toledo were powerful brokers in the political and religious affairs of Spain).

There were some very day-to-day practical reasons as well. Felipe II could model the city as he wished without provoking major social conflicts. Also the location was well positioned close to several major crossroads, and the Manzanares River with its wells could sustain a large population.

Madrid also had some drawbacks. It had no outlet to the sea and was not an economic powerhouse. An alternative might have been Seville, but it would appear that Felipe II preferred to keep his new capital in the region of Castile. And his father, Carlos V, had held court in Madrid in the past.

Finally Madrid was surrounded by forests, animals and good weather, and Felipe II liked spending long days hunting in the region.

Madrid - then what?

Once Felipe II had transferred his capital to Madrid, he decided to start a major construction program. So along with El Escorial, Aranjuez took on some importance. The administration of the state was now located in Madrid, sufficiently far from Toledo the former capital of the kingdom and the seat of the Primate of the Catholic Church. Aranjuez was not far from Toledo, and the territory belonging to the crown could be extended and enhanced to provide supplies to both Toledo and Madrid.

The idea was to transport supplies and products using the Tagus (Tajo), and its main tributary, the Jarama. Navigability around Toledo was studied, as was the route through to Lisbon. A complex hydraulic program was started with a canal system. Exploiting a dam built in the times of Carlos V, numerous waterways were opened up allowing irrigation of the entire valley.

Aranjuez - early days

It was in 1139 that Alfonso VII (1105-1157) finally recovered the lands of Castile, including the two villages, Aranz and Alpajés. Aranjuez became a definitive Christian conquest in 1178 and was included in the lands held by the Orden de Santiago.

Because Aranjuez is located in a broad valley where the Targus and Jarama join, the area forms a kind of natural oasis in the dry region south of Madrid. When the lands were reconquered the Christian Kings encouraged their vassals to settle the region. Between the 13th and 15th centuries the lands were more or less intensively cultivated, mainly by the Mudéjar. In 1387 Lorenzo I Suárez de Figueroa, master of the Order of Santiago, built a recreational palace, which also served as a hospital for knights wounded during the war with the Muslims. The building was made of stone and brick, with rooms situated around a large courtyard. There were two floors divided by galleries sitting on white stone columns, and the decorations were according to Gothic norms of the period. A bridge spanned some irrigation channels and linked the building to orchards and gardens.

It is known that the royal family stayed in the palace at various occasions. In 1489 the Catholic Monarchs became masters of all military orders and in 1493 the Order of Santiago was incorporated into the Spanish Crown.

So from 1489 the Aranjuez recreational palace became the spring residence (Residencia Real de descanso) for the kings of Spain, and this remained the case until the end of the 19th century. However it was during the reign of Carlos I that it was decided to make Aranjuez a comfortable place for the royal family. In 1534 Carlos V, the father of Felipe II, created the Real Bosque y Casa de Aranjuez, planting what would later become the future gardens of Aranjuez. It is also said that Felipe II stayed in Aranjuez in 1531 to recover from some childhood diseases.

Later it was Felipe II who decided to build a new palace on the same site as the old recreational palace, and he incorporated the Jardin de la Isla originally created by the Catholic Monarchs. The story goes that when Ferdinand II became the Grand Master fo the Order, Isabella I developed a fondness for the island, and it was renamed Jardín de la Reina. Later Carlos V and Felipe II turned the area into a kind of nature reserve.

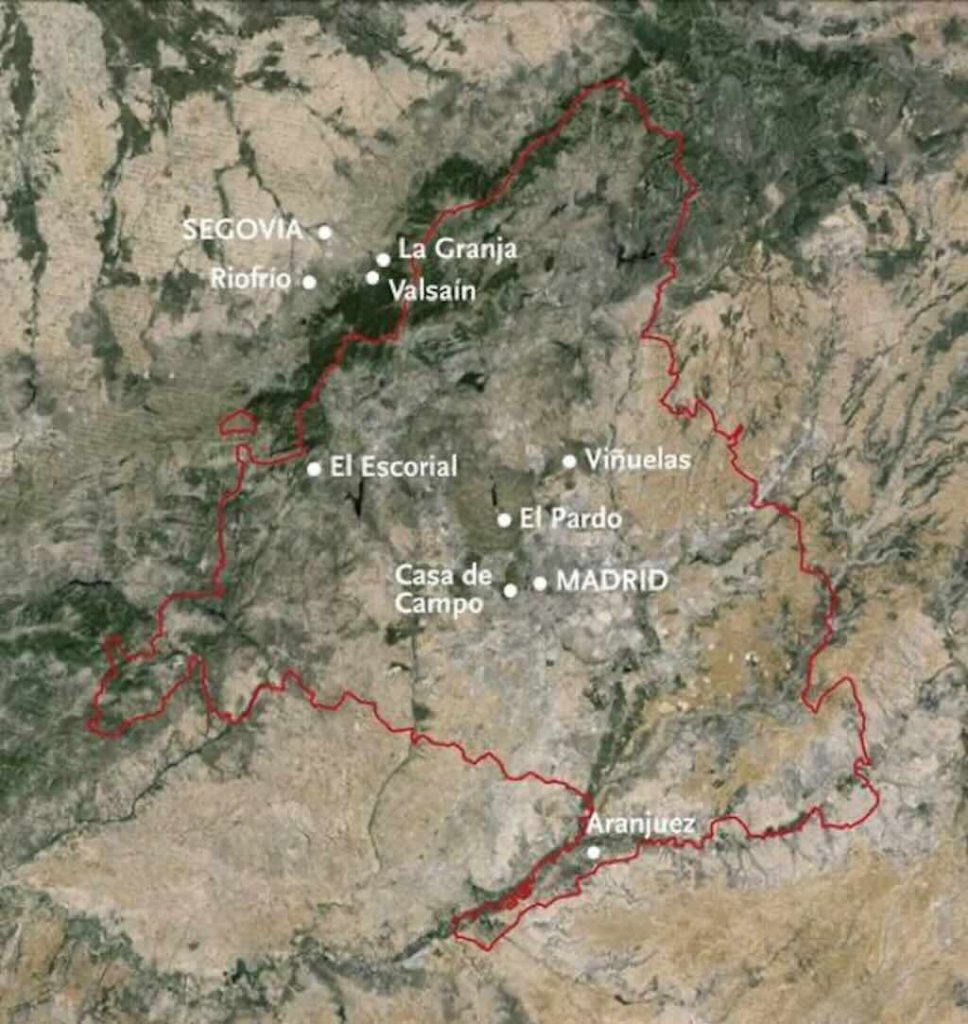

What Felipe II decided to do was change the traditionally itinerant lifestyle of his predecessors and settle his government in Madrid. What he then did was to complement this with a ring of residences within a 50-60 kilometre radius. This included two major country palaces, Valsain and Aranjuez, the retreat at La Fresneda, several hunting lodges (including El Pardo), the palacio in El Escorial, all linked together by a network of modest overnight stops. This allowed Felipe II to enjoy his passion for hunting and remain in contact with his government. It also created a settled, centralised authority and government, and at the same time introduced a new lifestyle where he was no longer dependent upon the castles of the Spanish nobility.

Felipe II went so far as to issue decrees concerning the governance of Aranjuez. This included the decision that only the monarch’s servants could live in the town, even when the court was present. Nobles and ambassadors who wished to be close to the King had to lodge in nearby villages (this rule remained until 1750).

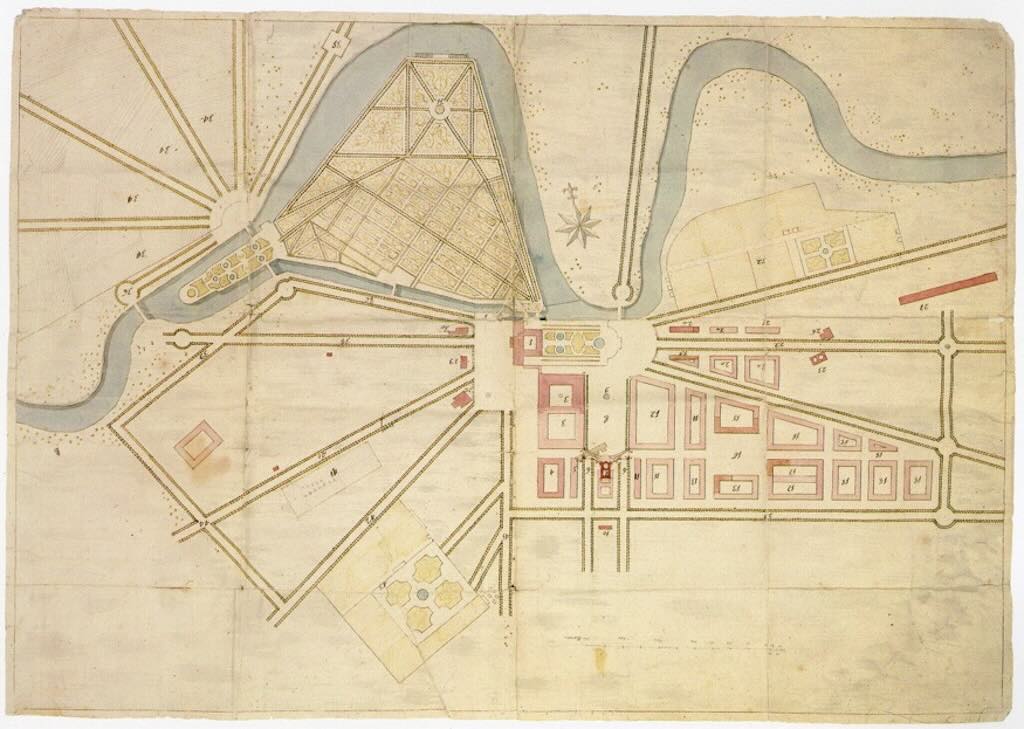

We are going to introduce a modern-day map of the lands around Aranjuez, so that we can more easily identify the different works initiated by Felipe II.

This map is on the web and a large version can be downloaded here.

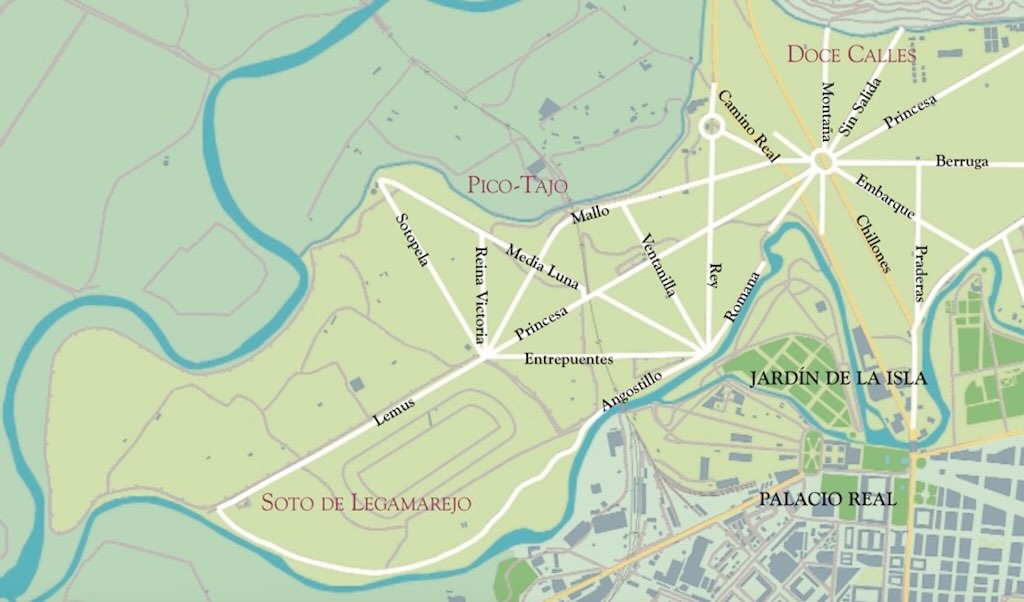

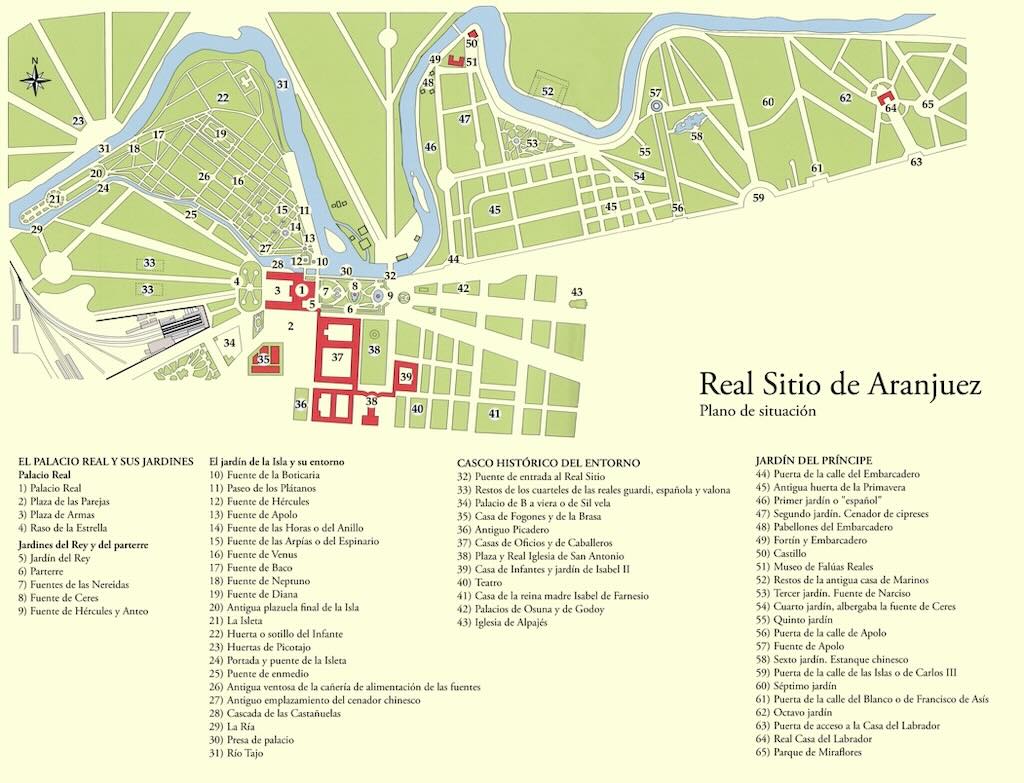

What Felipe II did was establish firm guidelines on how Aranjuez should be developed. He fixed rules on the hydraulic works needed, the management of the orchards, and the construction of the Las Doce Calles (the Twelve Streets) to be built at the extreme northeast of the site. He decided on the Calle de la Reina that ran though the gardens to the east. He established the Huertas del Picotajo (no.23) and the layout of the Huertas de los Negros (that later became the Jardín del Principe or Garden of the Prince, no.44 through to no.65). He decided on the Jardín del Ray (Garden of the King, no.5) and the Jardín de la Isla or Isla de la Reina (Garden of the Island or Island of the Queen, no.10 through to no.31). And he decided on the positioning of the Casa Real, la Capilla Real, la Torre de la Capilla, and the Casas de Oficios (the palace, chapel, tower and offices).

The new palacio of Felipe II was designed by Juan Bautista de Toledo (1515-1567) and executed by Juan de Herrera (1530-1597) and Gerónimo Gili (who died in 1580). Juan Bautista de Toledo started his career in Rome but by 1561 he was ‘Arquitecto Real‘ and responsible for the planning of El Escorial, La Fresneda, and Aranjuez. Juan de Herrera started his career with the work at Aranjuez and continued the work on El Escorial after the death of ‘de Toledo’. It is said that with Felipe II, Juan de Herrera adopted a more sober style with the use of bare granite (this became known as the Herrerian style).

Between 1560 and 1567 ‘de Toledo’ worked on the building of the new palace chapel and modifications of the gardens. Already in 1557 Felipe II had more or less decided that he did not like the medieval style palacio, and Juan Bautista de Toledo was seen as a ‘renewal’ architect. After his death other architects carried out the re-construction in accordance with his original plans. We should remember that ‘de Toledo’ had ‘cut his teeth’ as Michelangelo’s chief assistant at St. Peter’s in Rome, before he moved to Naples to supervise projects for the Spanish Viceroy. What ‘de Toledo’ did was keep the square shape of the old building, the interior court, and towers in the corners.

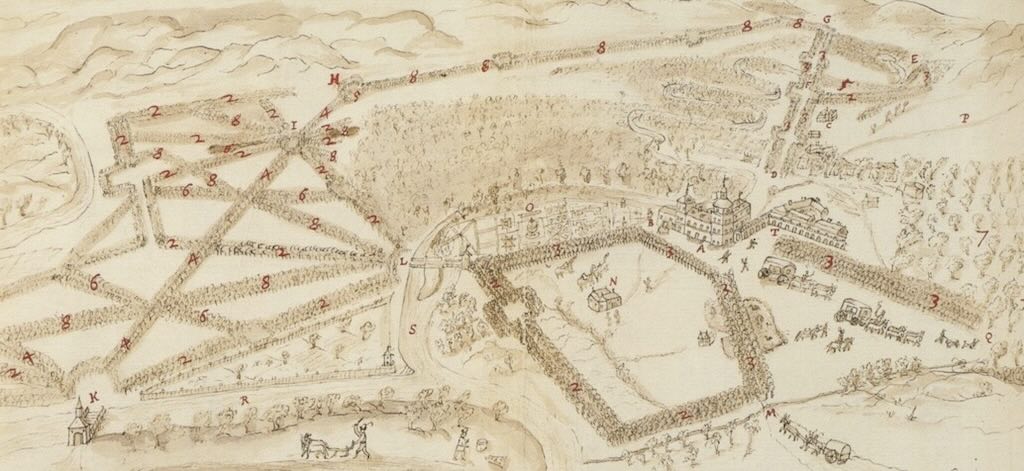

Above we have a view of Aranjuez dated from 1598. The numbers correspond to a descriptive footer on the drawing. Below I have zoomed in on the central part with the buildings.

Now according to the footer we can see the work of ‘de Toledo’ with A being the new palacio, B being the older, original palacio, O the flower gardens, T the offices, and ‘2’ might designated poplar trees.

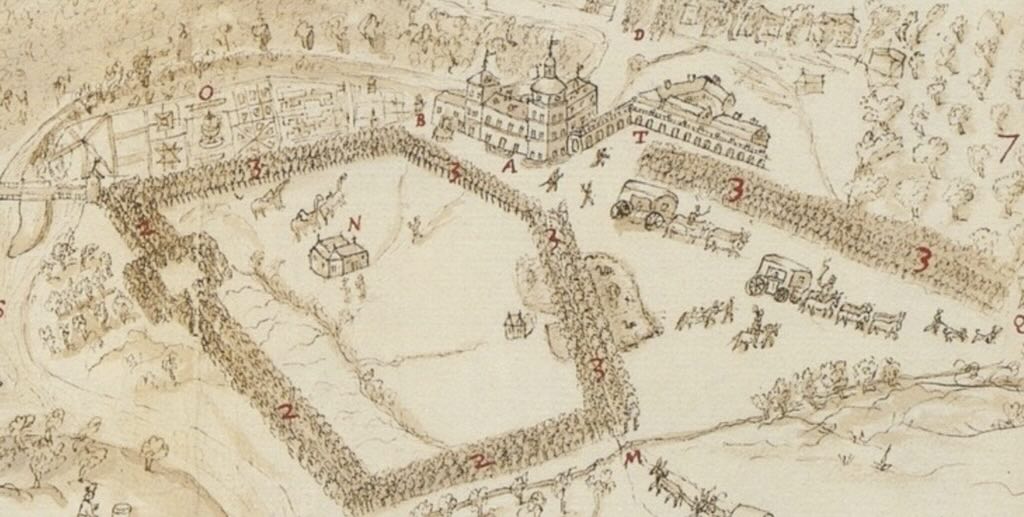

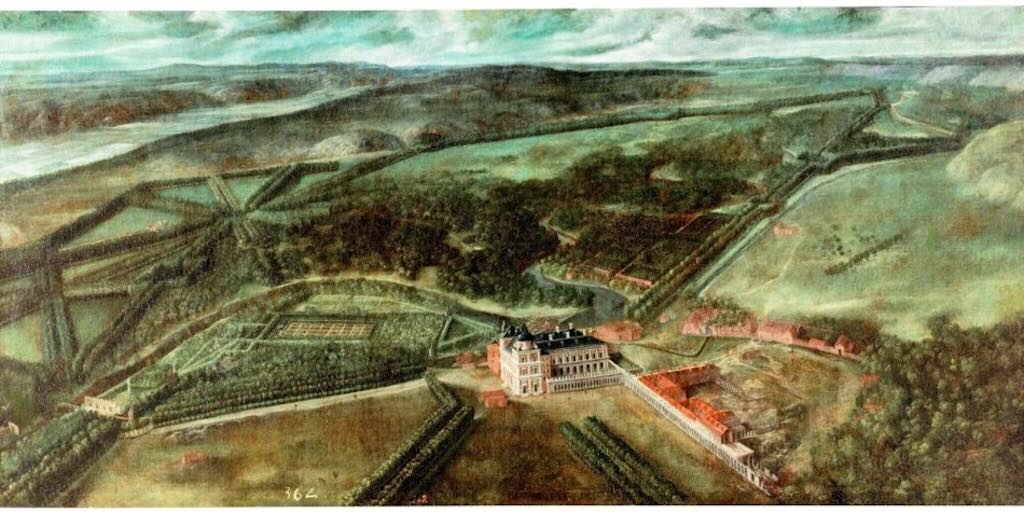

Below we have a view that probably dates from 1668-69 and shows the new palacio next to the original palacio (the small building hidden on the left).

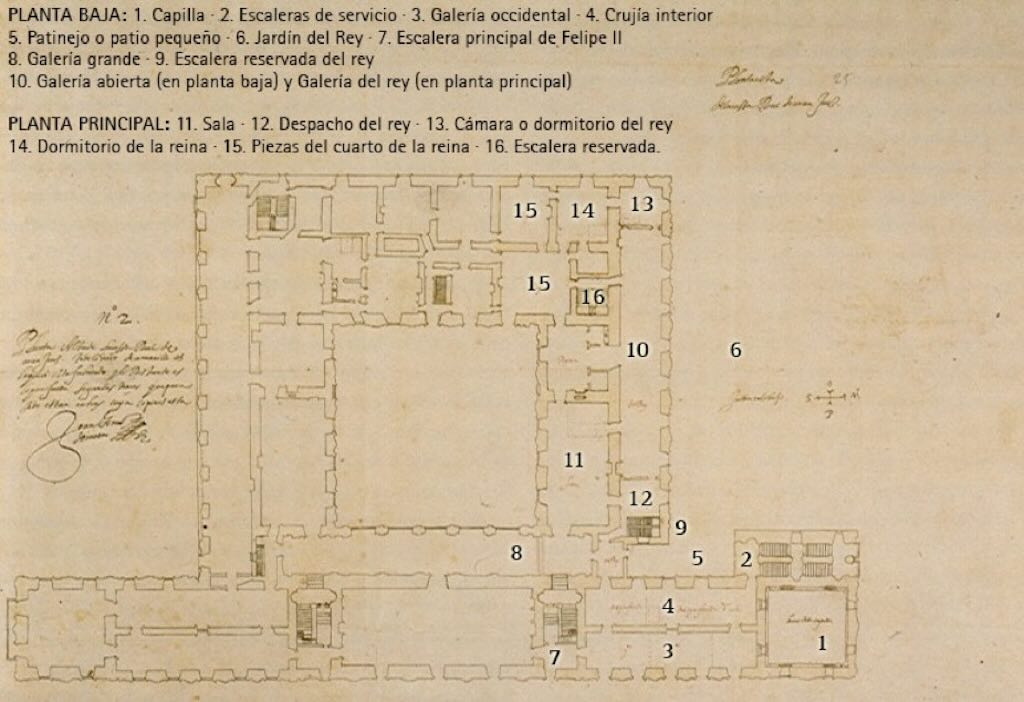

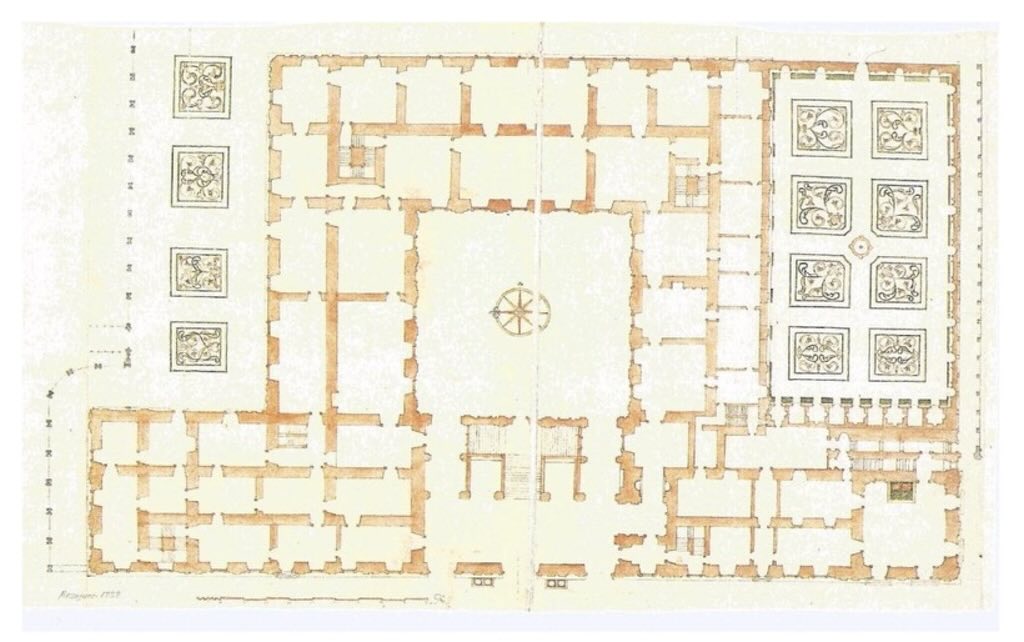

It would appear that Juan Gómez de Mora (1586-1648), made copies of the original project of Herrera (see below).

The plans show La Capilla del Rey under the tower (no.1). El Jardín del Rey (no.6) had a gallery on the ground floor and another one was located on the upper floor (no.10) that was connected to the Dormitorio del Rey (King’s Bedroom no.13), and adjacent to the Queen’s Bedroom (no.14). Subsequently, Felipe IV (1605-1665) ordered the decoration of the upper gallery (no.10) with a collection of landscapes.

The disposition of the King’s and Queen’s bedrooms would change with successive reigns. Felipe V (1683-1746) moved the royal rooms to the exterior eastern corridor, so that they could observe the Jardín del Parterre. Carlos III (1716-1788), Carlos IV (1748-1819) and Fernando VII (1784-1833) took rooms in the north wing. Finally Isabel II (1830-1904) continue in the north half of the palace, but left the south wing to her consort Francisco de Asís (1822-1902).

Above we have a painting of Aranjuez dated 1636, and below we have another painting of the same date. But the below painting is actually of a model created by Juan Gómez de Mora for the planned extension of the palacio.

Throughout much of the 17th century building work was stopped. The above plan for an extension was ordered by Felipe IV, but it was never built. However, numerous fountains and statues were added to the Jardín de la Isla. For example, the fountain ‘El Espinario‘ or Fuente de las Harpías, also known as “El Niño de la Espina” is one of the most symbolic.

This statue is a copy of an original statue found in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. This copy was made with a mould brought from Italy by Velázquez. The statue was made by the sculptors Juan Fernández and Pedro Garay (both from Toledo) and was completed in 1617.

The ‘boy with the thorn’ represents a boy sitting while removing a thorn from the sole of his left foot. Some historians believe that this sculpture represents a shepherd named Martius, who carried a message with such diligence, that he only stopped to remove a thorn in his foot when he had finished his mission. Others believe that it is simply an unknown athlete.

The statue is part of an interesting sculptural set consisting of four marble columns with their Corinthian capitals. Sitting on the columns are the figures of the Harpies, i.e. Aello (‘storm swift’), Celaeno (‘the dark’), Ocypete (‘swift wing’) and Podarge (‘fleet-foot’). Each has three jets coming out of their mouths and their breasts give off water towards the central.

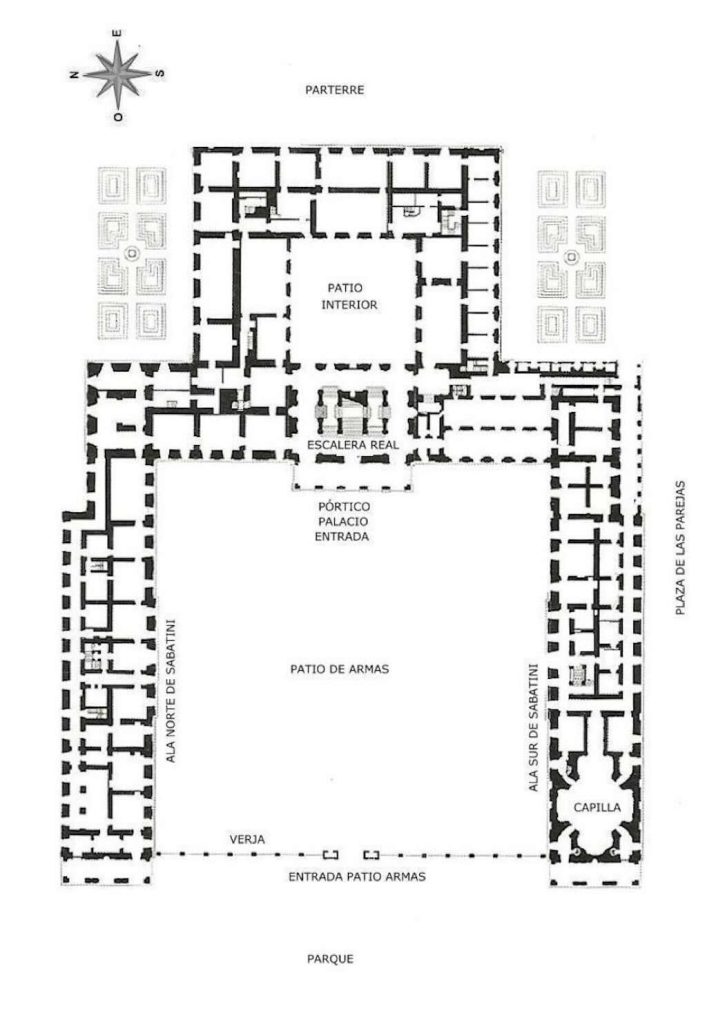

The four columns were changed in 1967, and the central statue was dismantled and replaced by a plastic copy in 2010.

The above view shows many of the essential features of the Aranjuez. We can see the Palacio Real with Plaza Eliptica in front and the Jardín del Parterre at the back. Above we can see the very large Plaza de San Antonio with the Fuente de la Mariblanca. We can see the Plaza de Parejas, the smaller Patio de Oficios, and the larger Patio de Caballeros (see below). A few sources call the patios ‘Oficios de boca‘ and ‘Caballeros Gefes y Gentileshombres‘.

The Casa de Oficios had been started by Juan Bautista de Toledo and continued by Juan Herrera, and its construction continued during the 17th century. But with arrival of Felipe V the Casa de Oficios would be expanded, and the so-called Casa de Caballeros would also be started according to a project by Gómez de Mora. It would be Fernando VI (1713-1759) who would complete the work with the creation of their famous interior patios. Some reports mention Santiago Bonavía (1700-1760) as taking over some of the construction work ca. 1730, and that Jaime Marquet (1710-1782) completed the work with the patios.

Some texts point to fact that the Casa de Oficios was something of a tradition with the Habsburg’s. The Austrian tradition was that rulers would be surrounded by a multitude of different ‘trades’, whereas it would appear that the household of the Catholic Monarchs was much more ‘streamlined’. With the Habsburg’s the culinary work would be carried out by a swarm of people in the kitchens, each would be allocated very specific culinary functions. And they would work together in what was called ‘oficios de boca‘, in part because the Spanish vocabulary was not extensive enough to give a name to every different culinary function.

Also we should not forget all the other tasks such dealing with merchants, fishmongers, butchers, and delivery people. Then there were those who managed the crockery and glassware, and those who served at dinner. There was even a person to remember what had been served, and who ate what, so as to avoid the same food being prepared too frequently. And finally the leftovers from the royal table would have to be properly distributed among the local subjects.

A view that has been expressed more than once was that Carlos V (1500-1558) saw Aranjuez as a hunting park, and he even let his son Felipe II train himself with a crossbow in the park. Experts have noted that both Carlos V and Felipe II expanding Aranjuez by buying local farms, with the priority to expand the territory and turn the area in to an ever larger hunting park. Felipe II expanding the natural habitat for fallow deer, wild boar, foxes, etc. so as to improve the hunting. Aranjuez became the spring residence, simply because the hunting was best in spring. Below we have a scene from 1540 with deer hunting and the palacio in the background.

Above we have a scene from Aranjuez in 1640. We see a corridor created in which the animals were released so that they could be killed by the court. Another technique used at Aranjuez was for the dogs to drive the deer towards the river, and the courtiers would wait with their crossbows in boats in the river.

Not a particularly ‘fair’ way of hunting.

Aranjuez - the Bourbons

It was the Bourbons that ended up defining Aranjuez, turning it into a model of a courtly city, while maintaining its character as a great agricultural exploitation. Below we have a painting dating from 1720-1724 where we see the palacio from an unusual perspective, that is over the Casa de Oficios. I wonder if the building with the tall pointed roof was not a smokehouse?

After the War of Succession (1701-1714), Felipe V (1683-1746) ordered that the palacio be finished, and that some modifications be made to the gardens.

Above we can see the plans dating from 1728, and below the plans of Santiago Bonavía dated 1750.

Between 1715 and 1727 Felipe V ordered the destruction of the old palacio and the completion of the eastern wing. This included the building of an entrance porch and imperial stairway (completed in 1745). He also formalised the Jardín de Parterre, introduced a small island prolongation to the Jardín del Principe, and added a Jardín de la Reina (now disappeared). A new access was built to the Jardín de la Isla via a stone bridge.

During the reign of Fernando VI, which lasted from 1746 to 1759, he completed the building according to the original plans. The north wing was built and a dome in the north wing was planned to house a theatre. A portico entrance was added to the central sector, with sculptures of Felipe II, Felipe V and Fernando VI.

He also extended the small court city to the south. This followed a rigorous orthogonal scheme of regular blocks of wide streets and tree-lined promenades parallel to the porticoed Plaza de San Antonio. In addition a trident of avenues (Calle de la Reina, Calle del Príncipe and Calle de las Infantas) were built that aimed to unite the palacio with the gardens and the new city. It is said that Fernando VI and his consort Bárbara de Braganza (1711-1758) turned Aranjuez into the stage for splendid parties led by the castrato Farinelli (1705-82). Below we can get a feeling for these ‘parties’ in two paintings dated 1756.

It was Santiago Bonavía who worked on the decoration of the palacio from 1728 to 1759. He completed the main façade, created a principle balcony with an arcade portion, and decorated the facade with statues of past kings.

It was Carlos III (1716-1788) who completed Aranjuez, leaving the palacio as we see it today. His architect, Francesco Sabatini (1722-1797) added two naves (parallel wings) perpendicular to the central body of the palacio, creating a huge ‘Patio de Armes a la Francesa‘. The idea was to create a monumental ‘patio de honor‘ and to have at the end of one of the arms a chapel and at the end of the other arm in the north wing a theatre (never completed). The old chapel of Felipe II was converted into additional formal rooms. This work was complete in 1780.

Carlos III also initiated some modification to the orchards, transforming them into the Jardín del Principe. The garden was named as such for the ‘infante Carlos’, future Carlos IV, when he was Prince of Asturias. It was designed in 1784 by Pablo Boutelou, successor to the great dynasty of gardeners of the Real Sitio. The works of the garden and of the Casa del Labrador (a kind of ‘House of the Farm Labourer’ but intended for royal use) would be finalised during the reign of Carlos IV.

Carlos IV (1748-1819) also ordered some changes to the way the rooms were distributed, which affected the Porcelain Room of Carlos III and the Hall of Mirrors of Queen Maria Luisa of Parma (1751-1819).

Between 1848 and 1850 Isabel II (1830-1904) introduced a smoking room for her consort Francisco de Assisi. The room is decorated in the Neo-Nasrid style, and was inspired by the rooms in Granada.

In 1974 the ‘patio de honor‘ finally received its iron fence closure as originally imagined by Sabatini. Above we can see that the central patio was never closed as originally planned.

Aranjuez - the finishing touches

In this article the author noted that whilst diplomats were the most important group to visit Aranjuez (for obvious reasons), the site also attracted those who included Spain in the Grand Tour. Henry Swinbourne (1743-1803), the English travel writer, wrote in 1799 on Aranjuez “for here are numberless avenues of aged elms on a perfect level; green banks to rest upon, near a fine meandering river; fountains and shady groves; plenty of milk and butter, and vegetables in great perfection”. It looks as if Aranjuez slowly became included in the ‘sights worth seeing’ along with Granada and Córdoba.

In fact throughout the 18th century Aranjuez saw the planting of exotic arboreal species, increasing the tree-lined promenades around the palacio. From 1732, new streets, such as La Estrella, were lined with black poplars, lime trees and chestnut trees.

Carlos III insisted that the territory be organised so that spaces were delimited by tree-lined promenades, that pastures were set aside for the stud farms and the cattle farm, and that diversified crops were managed through a series of farmhouses.

For a more detailed review of the landscape and agricultural developments in Aranjuez check out this article, and below we have a painting dated from 1830 by the court painter Fernando Brambila.

As a final step before moving to the interior of the palacio we will spend a few minutes on the favourite architect of Carlos III, Francesco Sabatini (1722-1797) who ‘created’ or perhaps more precisely ‘finished off’ the Aranjuez as we see it today.

Wikipedia points out Sabatini was an early Neo-classical architect who drew his inspiration from Renaissance architecture rather than Roman or Greek ruins. So he was interested in symmetry, proportion, and geometry, and to achieve his objectives he used orderly arrangements of columns, pilasters, lintels, semi-circular arches, domes, niches and aedicula (small shrines). All this manifested itself in an interest in classical or ‘triumphal’ arches and gateways, corner towers, balustrades (also on roof tops), and courtyards.

While all this might look overly decorative, Sabatini was actually well known for his functional, sober and utilitarian architecture, probable in part due to his military education.

Sabatini added the two wings to Aranjuez as ordered by Carlos III. But the problem was to make the old and new coexist through some form of symbolic content. Also the addition of the two wings would change dramatically both the size of the palacio and the dimension of the urban spaced occupied, the word ostentatious comes to mind.

At the time (and still today) people approached the palacio from the side and back, and little was made of the main façade. What Sabertini did was create a monumental ‘patio de honor‘ that linked to the open gardens through a tree-lined fan of streets (highlighting regularity and symmetry). His use of cornices and balustrades remained a constant in the architectural modifications and renovations that would follow. With the new space provided in the wings, and the inclusion of a new Royal chapel, the entire court dynamics in the building changed.

As one observer wrote at the time “… The palace is not superb, but it has the look of comfort…“.

For more information on the building and restoration work check out this extensive analysis performed by Elitsa Vensislavova Bozhkova in her doctorate thesis on art history.

References

Patrimonio Nacional – Palacio Real de Aranjuez

Aranjuez, web de turismo y ocio

Aranjuez Cultural Landscape, Spain

El Palacio Real de Aranjuez y su Historia

La Casa de Oficios de Aranjuez, Gema Muñoz Garcinuño

Pequeños Parques y Parterres de Tipo Urbano, including an extensive article on the Jardín del Parterre de Aranjuez

Aranjuez, Sitio Real y Paisaje Cultural, José-Luis García Grinda

Web Fotográfica Del Real Sitio y Villa de Aranjuez, José Juan de Oro Durán

Audio Guía Teatralizada de Aranjuez, Audioguias Bluehertz, includes 178 mp3 audio tracts on everything from the Palacio Real, through la Fuente de Ceres, and to la Plaza de Toros

Aranjuez, Urbanismo y Arquitectura en el Paisaje, Magdalena Merlos Romero

Los Planos de los Sitios Reales Españoles Formados por la Junta General de Estadística (1861-1869), Luis Urteaga y Concepción Camarero Bullón

Pasión por Madrid, a blog that ran from 2010 to 2015

Aranjuez II – Historia del Real Sitio, Jorge Peñalver López, and the blog historiaenestudio

djaa – Solo cultura, Valencia y Benimàmet, looks to be a personal blog, but has some interesting webpages, including one on the Palacio Real de Aranjuez

Huertas de Picotajo en Aranjuez, looks to be a webpage on the blog of Pilar Álamo that ran from 2008 to 2016

Paseos Arbolados de los Sotos Históricos de Aranjuez

Descripcion Histórica Del Real Bosque y Casa de Aranjuez, Juan Antonio Álvarez de Quindós y Baena