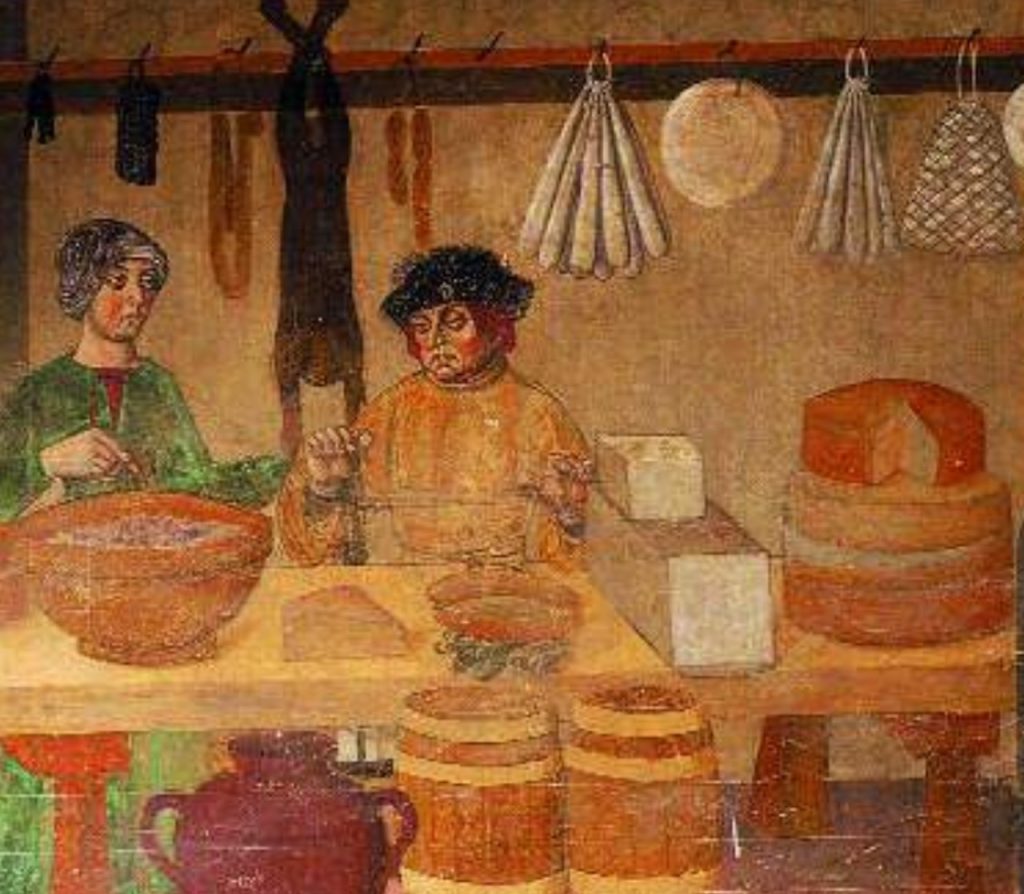

“Vacherinus”, “Seracio”, “Faontines” are the terms used from 1270 until the 16th century to indicate the cheese obtained from whole cow’s milk produced in the Aosta Valley. The first iconographic evidence dates back to the 15th century and is found in a fresco in the Castle of Issogne.

From the 18th century the term Fontina definitively imposed itself on the others.

On the etymology of the name the versions are conflicting. In various documents, the name Fontina dates back to the ‘De Funtina’ family, then a hundred years later ‘de Fontines’. There are those who instead connect it to the name of the Fontin mountain pasture, in the municipality of Quart. And there are those who derive its origin from the name of the small municipality of Fontinaz (Saint-Marcel), and yet others suggest it was simply the surname of a family of cheese producers.

The first official document bearing the term ‘Fontina’ dates to 1717, and is kept in the archives of the Gran San Bernardo Hospice.

For many centuries Fontina was produced where it was possible to have enough milk, and this meant cows in the mountain pastures. And traditionally it was “gli arpian“, the shepherds, who prepared it. During the winter, almost all families in the Aosta Valley had only one, or maybe two or three cows, just enough for the family. Only during the 1800s dairies were established and the milk to be processed was shared in a cooperative.

The Valle d’Aosta cows have a variable milk production during the year, lower overall in quantity than that of other breeds, but of higher quality. The cows’ diet, mainly composed of alpine grasses, also determines the nutritional content of the milk, which varies slightly between summer and winter.

Cheese basics

To get a quality cheese the raw material must have, in addition to the mandatory hygienic-sanitary requirements, a good balance between the casein content, the mineral composition and the acidity. These are the main factors that interact during the rennet coagulation of the milk, and during the syneresis and purging of the curd.

The milk, and consequently the curd, must also provide a good basis for the development of the acidifying lactic microflora, which depends upon both the presence of growth factors and the absence of antibacterial substances.

Given these premises, the cheesemaker applies very precise technological interventions, aimed at obtaining curds in which those complex biochemical mechanisms can easily be triggered. During maturation, this determines the appearance, texture and aromas that characterise a cheese.

What makes a Fontina cheese special?

Fontina is a Protected Designation of Origin cheese (DOP Denominazione di Origine Protetta), as such its production is highly regulated in terms of production, maturing (aging) and portioning.

Fontina is a semi-cooked fatty cheese made with full-fat cow’s milk from a single milking.

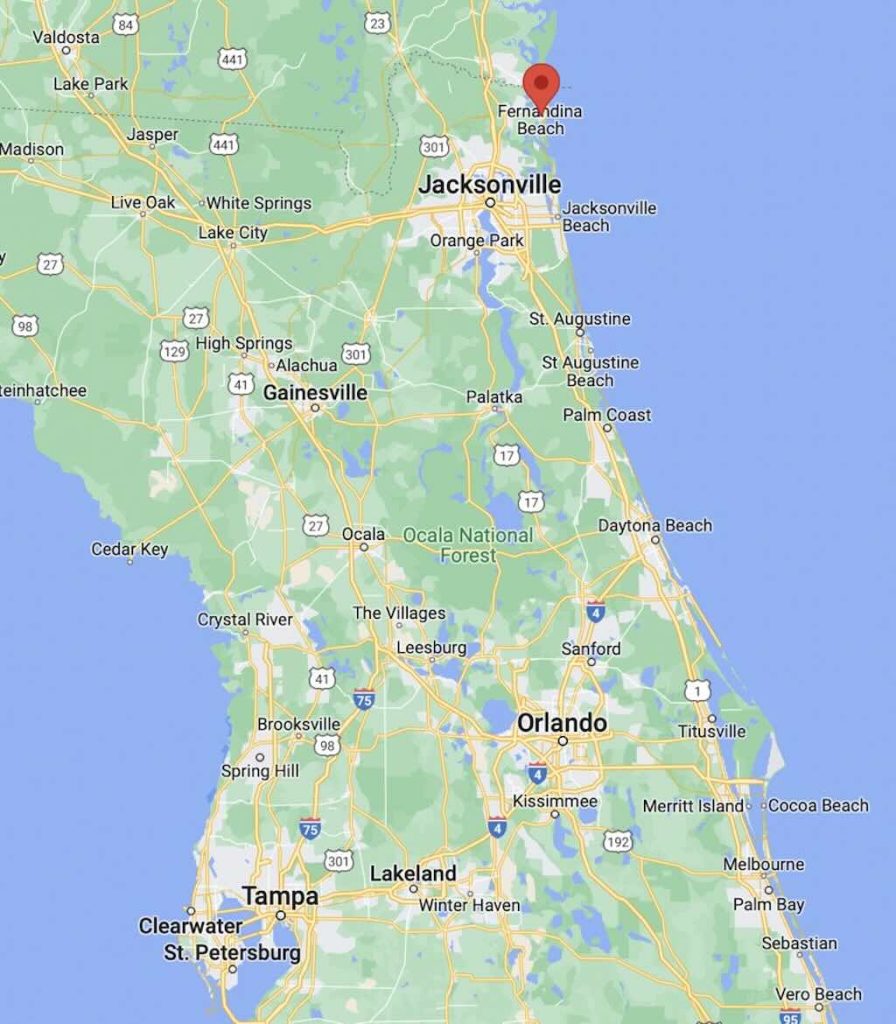

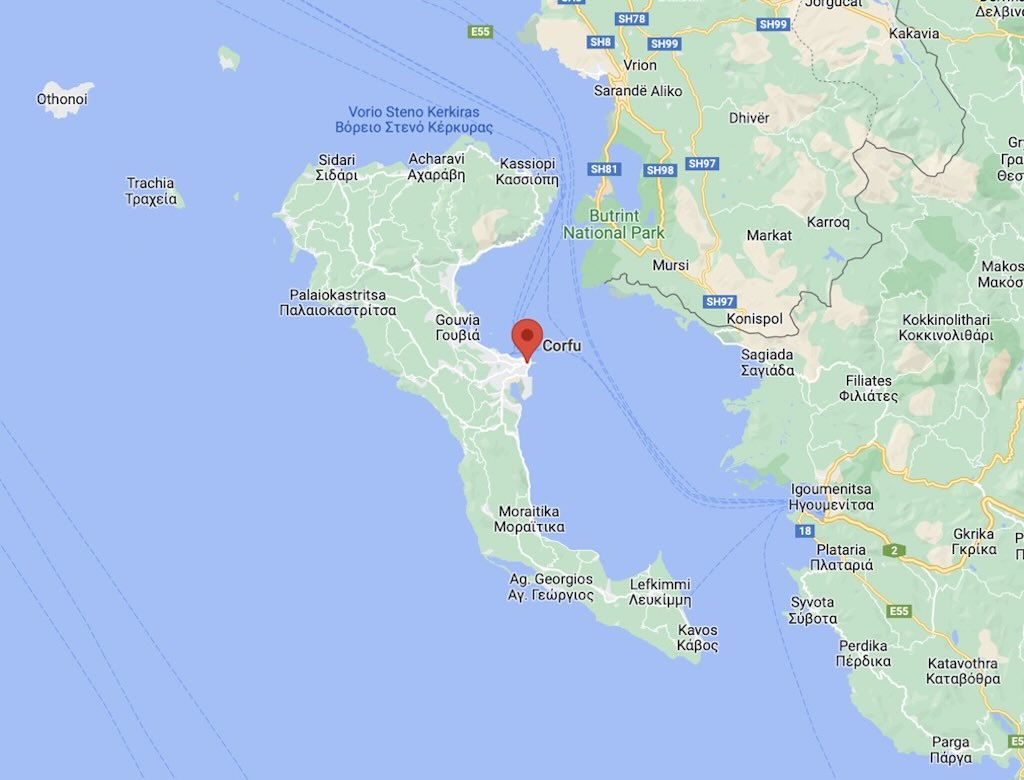

Fontina can be produced, matured and portioned anywhere in the Valle d’Aosta.

The milk used must be produced in the Aosta Valley and must be crudo (raw and not pasteurised), intero (full cream), coming from a single milking (una sola mungitura) of bovine belonging to the Valdostana breed (Pezzata Rossa, Pezzata Nera, Nera-Castana) fed on a diet of hay and green grass (fieno ed erba verde) found in the Aosta Valley. It is possible to use concentrated feeds compliant within the current legislation (which includes limited quantities of sunflower flour, organic flax, maize and soy, corn gluten semolina, but all ensiled or fermented fodder are prohibited).

It’s worth noting that all of the following feed is prohibited, flours and proteins of animal origin, flours and oils of animal and vegetable origin, seeds, vegetable and fruit roots, rice, wine and beer by-products, and any industrial by-products such as sucrose, glucose, yeasts, molasses, etc.

And also all types of nitrogen sources, antibiotics, hormones and/or stimulants, silica, chemically treated straw, and dry or fresh bread, are also all prohibited.

One question often asked is would it not be simpler and safer to use pasteurised milk? However, this would compromise the richness in vitamins of Fontina and would alter its aroma, physical characteristics and taste, and the fact that it can be digested well by everyone, even by less robust stomachs. By pasteurising the milk the production costs would be significantly lower, but Fontina would become the same as other cheeses manufactured elsewhere.

The cows and the milk

Fontina is made from the milk of three local breeds, Valdostana Pezzata Rossa, Pezzata Nera and Castana. Their yearly cycle is divided into three periods, firstly the autumn calving, then the winter-spring period of maximum lactation and finally the summer period and the end of lactation.

Starting from 1932, the Valdostana Breed standard was defined and approved by the Italian Ministry in 1937. Two breeds were initially defined, the Valdostana Pezzata Rossa and the Valdostana Pezzata Nera. In 1985 the Castana breed was also admitted combined with the Valdostana Pezzata Nera and in 1995 two Genealogical Books were definitively approved, one for the Valdostana Pezzata Rossa and one for the Valdostana Pezzata Nera-Castana.

The Valdostana Pezzata Rossa, like the other red piebald breeds that populate the base of the Mont Blanc massif, very probably derives from the piebald cattle originating in Northern Europe introduced by the Burgundians towards the end of the 5th century.

It is the most widespread autochthonous breed in the western Alps, where it has adapted perfectly to the geographical and climatic conditions. It is characterized by a red dappled coat with colour variations from light red to deep red. The head is generally white with short, thin, red ears. The abdominal region, the distal parts of the limbs and the tail are white. The light and yellowish horns are thin and directed forward and upwards. The limbs are short and vigorous, with broad joints, strong hocks and short, solid shins.

The Valdostana Pezzata Rossa is characterized by a great locomotor capacity, even on steep slopes, thanks to robust limbs, extremely resistant and hard nails and a relatively ‘light’ constitution (live weight around 500 kg).

Furthermore, its particular adaptability to difficult climates and resistance to common pathologies means it can be exploited in areas where more demanding breeds from a food and management point of view can’t be bred profitably. In addition, these cows show excellent fertility, understood as easy calving and high reproductive efficiency. They are also long-lived, frugal and are characterised by a marked aptitude for the use and enhancement of coarse forage.

The production level in milk is appreciable when compared to the size of the animal, to the food needs and above all to the traditional breeding conditions with all the cows in lactation going up to the mountain pastures.

In addition to possessing the same characteristics of rusticity and frugality as the Valdostana Pezzata Rossa, the Valdostane Pezzate Nere and Castane cows are characterized by a greater mass and a certain impetuosity and vitality which takes the form of a ritual of dominance within the herd.

The interest of breeders in this breed is not to be found so much in their productivity as in their nature, which leads the cows to fight each other to establish the hierarchy in the pasture.

In the Aosta Valley, for the past fifty years, ‘Batailles des Reines‘ have been organised from spring to autumn, i.e. fights between the pregnant cows of this breed. The innate instinct for territoriality and the hierarchical dominance of the cows translates into ritual attitudes that precede a bloodless fight that leads to the identification of the strongest and most combative cow and her proclaiming as Queen.

The ‘Reines’ in addition to being a symbol of prestige for the breeder, acquire a notable commercial value and their fights have become important socio-cultural events that also attract spectators from the countries bordering the Valle d’Aosta.

The feeding of the dairy cows is essentially based on the administration of hay during the winter, while grazing is practiced in the other seasons.

The typical organisation of the Aosta Valley farm includes several blocks of land distributed in the valley floor (fondovalle), in the ‘mayen‘ (between the valley floor and the mountain pastures) and in the mountain pastures (nell’alpeggio).

The latter implies the practice of transhumance from the transitions at lower altitudes to those located over 2,000 m above sea level to follow the vegetative cycle of the pastures and always have the forage resources necessary to cover the needs of the cows during lactation.

This type of traditional management also allows the farmers in the valley floor, during the summer, to carry out the indispensable haymaking to produce the hay to be used in the winter season.

Another aspect linked to the exploitation of the pasture during the summer is the consequent concentration of calving in the winter months (95% of calvings are concentrated from November to March). This practice allows farmers to look after newborn calves and the ‘fresh’ cows in the stable and bring cows already in an advanced stage of lactation with lower energy and protein requirements to the pastures.

It is clear that the cyclical changes in feeding has an effect on the composition of the milk, and the local environmental, genetic and physiological factors all play a role in the make up of the milk found in the Valle d’Aosta.

The collection of milk by machine milking (although most of the plants still use buckets) prevails in the period of maximum lactation, compared to hand milking, which is still practiced in mountain pastures.

In the farms at the bottom of the valley modern livestock shelters have been built, but such buildings can’t be justified in the high pastures, up to an altitude of 2,700 m. From a certain point of view, this is positive because, thanks to the passion, tenacity and stubbornness of the breeders, traditional milking still happens in a relatively uncontaminated environment. It has been stated that that modern cheese-making difficulties derive from the paucimicrobial loads (containing few microbes) of the milks coming from modern farms. This problem does not yet concern the mountain pastures, where more often than not, thanks only to the action exerted by the local microflora, the milk is normally transformed into Fontina, with excellent results.

The boiler in which the cheese is made is the fundamental link in the livestock-dairy production chain. At the permanent dairies in the bottom of the valley, active from December to May, the milk is collected and mixed from several farms. While in the summer period of grazing in the mountain pastures there is, always twice a day, a separate batch transformation of milk to cheese.

The milk in the mountain pastures is therefore still subjected to artisanal processes, while in the valley dairies this is not possible, given some of them can receive in excess of 100 quintals of milk per day.

Transforming milk into Fontina must necessarily be adapted to the behaviour of the milk, essentially with reference to its coagulability and the ease of purging and acidification of the curd. The cheesemaker has the difficult task to remain compliant with the Production Regulations, and yet make the most of the milk and obtain a quality Fontina.

A semi-cooked cheese, obtained from raw milk, such as Fontina, will always display a reasonable variability in the organoleptic standard, which indeed, within well-defined limits, even becomes one of its characterising elements.

For readers who are interested in the detailed production process and the permitted variations, have a look at the reference at the end of this post. However, it’s worth stressing that Fontina is characterised by:-

- Fresh milk that has not undergone refrigeration or heat treatments. Its microflora, its constituents with biological activity such as enzymes, vitamins, hormones, the number of somatic cells are not modified by any direct intervention in the passage from the field to the dairy.

- Boiler milk is not standardized in terms of fat content, its acidity is natural and the use of any additives other than the coagulating enzyme is not permitted.

- The maximum firing temperature must remain below 50°C.

- The season lasts at least 100 days and takes place in environments where the humidity and temperature conditions are natural.

Production Regulations for Fontina leaves room only for a technology based on the use of rennet and physical actions in the boiler (breaking up, cooking and mixing of the curd), along with the use of native lactic ferments based on the advice of the Regional Technical Assistance Service.

Clearly it is essential that milk in the boiler is perfect from all points of view, and farmers are expected to apply the most rigorous and rational breeding techniques.

It’s also worth noting that both tradition and modern production technologies indicate that the processing of the milk must be carried out in the shortest possible time after each milking. This limits the proliferation of anti-cheese bacteria and exploits the natural bacteriostatic defences of freshly milked milk. It is known that these defences naturally weaken and disappear almost completely after a few hours.

In addition the milk coming from a cow that has recently given birth (colostrum) or is sick must necessarily be discarded. The presence of unsuitable milk, even from a single cow can cause damage to the whole boiler.

Transformation (trasformazione)

There are equally strict rules covering the transformation of the milk into cheese. The cheesemaker can resort to the use of autochthonous ferment cultures, Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii, Lactococcus lactis, collected in the regional strain library of the Institut Agricole Régional.

Before coagulation, the milk must not have been heated to a temperature exceeding 36°C. The coagulation of the milk must take place in traditional copper or modern ‘double-bottom’ steel boilers, by adding calf rennet. The dose of rennet must be distribute uniformly by vigorously stirring the mass, using a ladle. The boiler is then left at a temperature between 34°C and 36°C for at least 40 minutes. Care must be taken to not to knock the boiler, so as not to disturb the gelling action of the rennet. Once coagulation is complete, a very thin film forms on the surface of the coagulum which is removed with a spatula, as it remains stringy and difficult to amalgamate with the rest of the casein mass.

The clot (coagulo) must then be broken up to obtain curd granules (granuli di cagliata) with dimensions comparable to a grain of corn. This starts with the help of the spannarola (a kind of large shallow ladle with holes in), to first break the clot into large blocks, turning it several times from the bottom upwards, so that the deeper layers emerge, thus eliminating any variations.

Rennin, a protein-digesting enzyme that curdles milk, is found in the last stomach of newborn ruminant animals (e.g. young cows), and it helps keep ingested milk in the bowels and favours better absorption.This feature has been exploited for thousands of years, taking the stomachs of young suckling animals culled to coagulate large quantities of milk and obtain a regular production of cheeses. This enzyme can be affected by temperature and the milk composition (casein, calcium and phosphorus content, acidity), so its coagulant action on caseins is a complex phenomenon. The more acidic the milk is, the shorter the coagulation time, but generally, for Fontina, after adding the dose of rennet, it takes 40-45 minutes to obtain a good curd.

Normally the curd is cut up use of a ‘lyre’ (una lira), taking care to obtain a very homogeneous size of the curd granules, the average size of a grain or rice kernel. After breaking up the curd, the lyre gives way to the ‘spino‘ (I think this a large balloon whisk), once manual and now mechanical, through which the mass is kept in constant stirring, quite energetically, so as to uniformly distribute the heat. This phase (fase di spinatura) must take place at a temperature between 46 °C and 48 °C. This process is then completed away from the heat until the cheesemaker decides that the curd granules are sufficiently well drained.

After a resting phase, of not less than 10 minutes, using a loosely woven cheese cloth (tele di tessuto) and a flexible steel sheet, the cheese paste is extracted from the boiler. The cheesemaker tries to extract portions of curd of about 9 kg. While still smoking the full cheese cloths are formed with a concave base (scalzo concavo) and a circular band with a slightly convex internal vertical surface.

The outer edges of the cloth are then folded over the dough and the wheels are placed under the press. The molds are stacked and pressed. By applying a pressure of about 1 kg per square centimetre, the whey comes out abundantly and is collected.

The intensity of the purging depends above all on the acidity of the cheese paste and whey, on the semi-cooking temperature and on the load applied under the press. The pressing must not be too strong otherwise it would impede the microorganisms to carry out a regular fermentation.

But the pressure must be sufficient to drain the whey. Already the pressure applied and the exact nature of the cheese paste can change both the texture and the taste of the final Fontina. Consumers today prefers a softer type of Fontina. Sometimes it is possible to achieve this, but sometimes not, since it is easy to encroach on an excessive softness and therefore arrive at drawbacks such as a bitter taste, an exaggerated flattening of the wheel, imperfect holes, a less attractive presentation with a dark or yellowish colour under the rind, etc.

If a cheese has been slightly over-heated and then pressed too vigorously, it become harder with a crumbly paste or internal flaking. This type of cheese takes longer to ripen and remains sweet for up to a year or more, however today the market prefers a softer, buttery Fontina.

The cheese wheel will be turned over and the circumference tightened 3-4 times to facilitating bleeding and dry the wheel.

At the first turning, a casein plate (placchetta di caseina) must be applied with an identification code of the shape and the graphic element identifying the product.

Before the last pressing phase, an identification plate must be applied bearing the number of the producer assigned by the Consortium appointed by the Ministry of Agricultural and Forestry Policies.

The wheels remain under the press for about twelve hours, i.e. until the next step in the process.

At this point it can be said that the task of the cheesemaker is finished, the milk has been transformed into a cheese.

It’s worth mentioning that after the Fontina curd has been extracted, a greenish-yellow liquid ‘whey‘ remains in the cauldron, which still represents about 85-88% of the milk. In addition to water, there are residual fats which can provide an excellent quality cream, and can be churned to provide butter. The residual liquid can be destined for livestock farms or the feed industry.

Turning, salting and scrubbing (rivoltamento, salatura e strofinatura)

So after 12 hours the milk has been transformation into a straw-coloured, rubbery, elastic and soft cheese, cylindrical in shape with a concave heel (edge).

Normally the fresh cheeses are immediately transferred to a damp (over 90% humidity) and cool (8 to 11°C) room, far from sources of heat, light or draughts. Some cheesemakers placed the wheels on a cold stone surface for 24 hours, in order to cool them as quickly as possible.

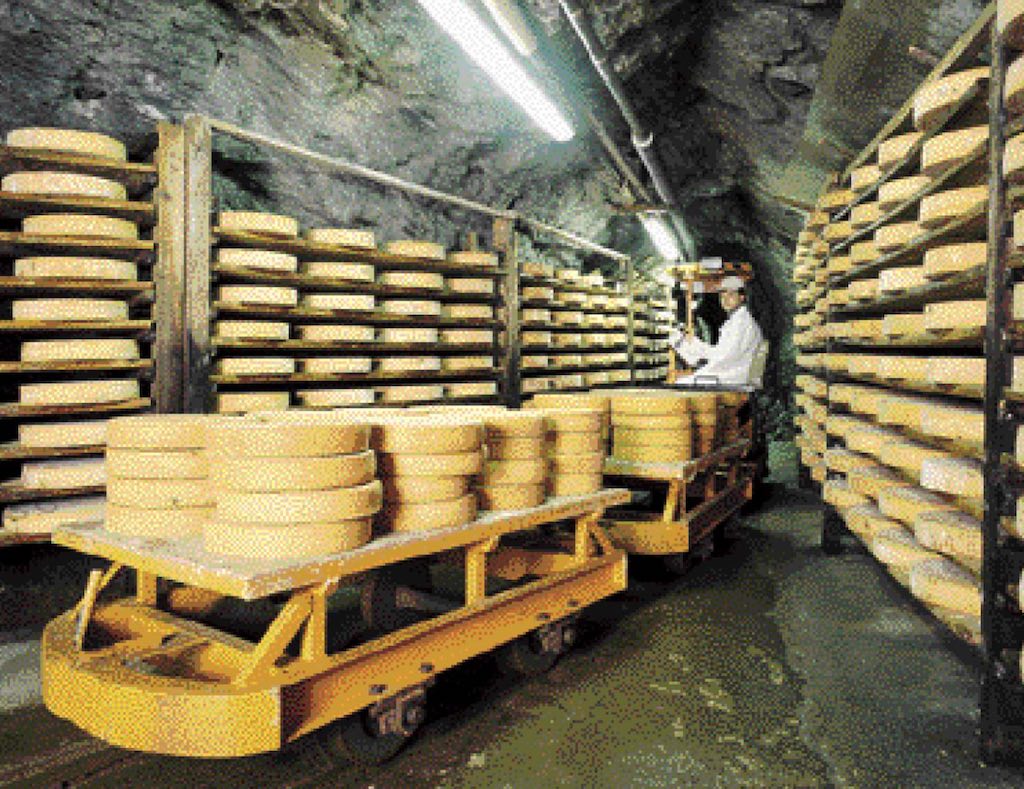

The wheels are then carefully placed on spruce fir (Picea excelsa) shelves ready for the next phase.

Next the individual wheels are turned, salted and scrubbed. The wheel is removed from the shelf and turned over for a light layer of salting (distribuzione a spaglio). Rubbing is made with brushes and a solution of water and salt. This process lasts for 3 months and takes place in the maturing warehouses (magazzini di stagionatura).

Some cheesemakers first treat the wheel with brine (la salamoia). This can be carried out within 24 hours of leaving the press and lasts for a maximum of 12 hours. This reduces the need for salting afterwards. It is said that dry salted Fontines are finer on the palate, therefore more appreciated by gourmets, which is why daily salting is preferred (although it’s more expensive and time consuming).

The straw-white colour of the surface, due to the scrubbing and salting, takes on a more intense colour day after day, which is pale at first, and then darkens as time passes. Slowly, under the beneficial action of the salt, a viscous patina (morchia, which does not translate well as greasy dregs or sludge) is created spontaneously and naturally on the surface of the wheels, which changes colour until it becomes, after three months, brown, sometimes even intense, more or less dark, for thickness of 1-2 mm. With many types of cheeses made from pasteurised milk, this morchia is removed, however, it is left on with Fontina.

According to the experts, salting not only enhances the flavour of the cheese, making it more tasty, but it also has an appreciable bacteriostatic action. It slows down the proliferation of any pathogenic microorganisms that could be found on the crust. The salt spread on the surface also contributes to the control of the absorption water content, but does not interfere with the microbial and enzymatic activity that occurs inside the cheese wheel.

It is therefore necessary to find the right balance between the need to leave the wheels without salt for 2-3 days in order to favour the activity of the lactic bacteria, and the need to salt the wheels to accelerate bleeding and reduce or remove excess lactic acid.

As a rule dry salting is always carried out every other day by rubbing the surface with salt water. This procedure lasts for about 70 days in the case of summer production, because at higher temperatures there is greater salt absorption, while when the warehouse is colder in winter, it takes longer to achieve the same results.

On mature and seasoned cheeses awaiting sale, care must be continued, salting is stopped but at least once or twice a week, the cheeses are rubbing with the same solution of water and salt. The drier the warehouse, the more these operations can be reduced, since the Fontina wheels, when they have reached a good salt concentration (about 2%), stay clean longer.

Maturing warehouses (magazzini di stagionatura)

The complex processes of transformation of matter can be summarised:-

- fermentation of lactose, which is transformed and becomes lactic acid due to the work of specific bacteria

- proteolysis, the transformation of proteins

- lipolysis, the degradation of fats.

The dough, white and crumbly as it was in the beginning, gradually becomes more buttery and greasy. Its colour, due to the effect of the carotenoids already present in the milk, gives it a slightly straw-coloured hue towards maturation, especially in summer production, because the cows feed on green fodder particularly rich in these substances.

The lactose already begins to transform into lactic acid in the boiler, progressively acidifying both the whey and the pasta.

The whey that remains in the cheese paste still contains an appreciable quantity of lactose and its transformation into lactic acid, started in the boiler, continues under the press, until the temperature conditions remain favorable for the lactic microflora. Other microorganisms take over later, releasing carbon dioxide as a product of the fermentative processes. This is concentrated in certain points inside the pasta, creating the classic ‘eye’, the shape of which gives the product its characteristic small holes.

Maturation must take place in special warehouses at a temperature between 5°C and 12°C, and with at least 90% humidity. These conditions can be found in caves traditionally used for the maturation of cheeses or reproduced through the use of conditioning technologies.

Before WW II, some local traders kept forms of Fontina for up to two years in the cool mountain cellars. With these cheeses some typical dishes were prepared, dishes that are no longer prepared today. Now a product with a normal period of maturation is preferred, without excesses, so around 3-4 months.

The semi-industrial approach adopted in the Aosta Valley has made it possible to avoid modifying the milk processing system. This has kept costs down, with a product that is not too industrialised. In Valle d’Aosta there has been no diffidence towards the adoption of innovative techniques nor opposition towards the mechanization of the processes, but an attempt has been made to safeguard that artisanal transformation system which, by itself, gives the cheese those particular characteristics that make Fontina completely different from other cheeses.

Fontina characteristics (caratteristiche del prodotto)

Fontina DOP must possess the following chemical, physical and organoleptic characteristics:-

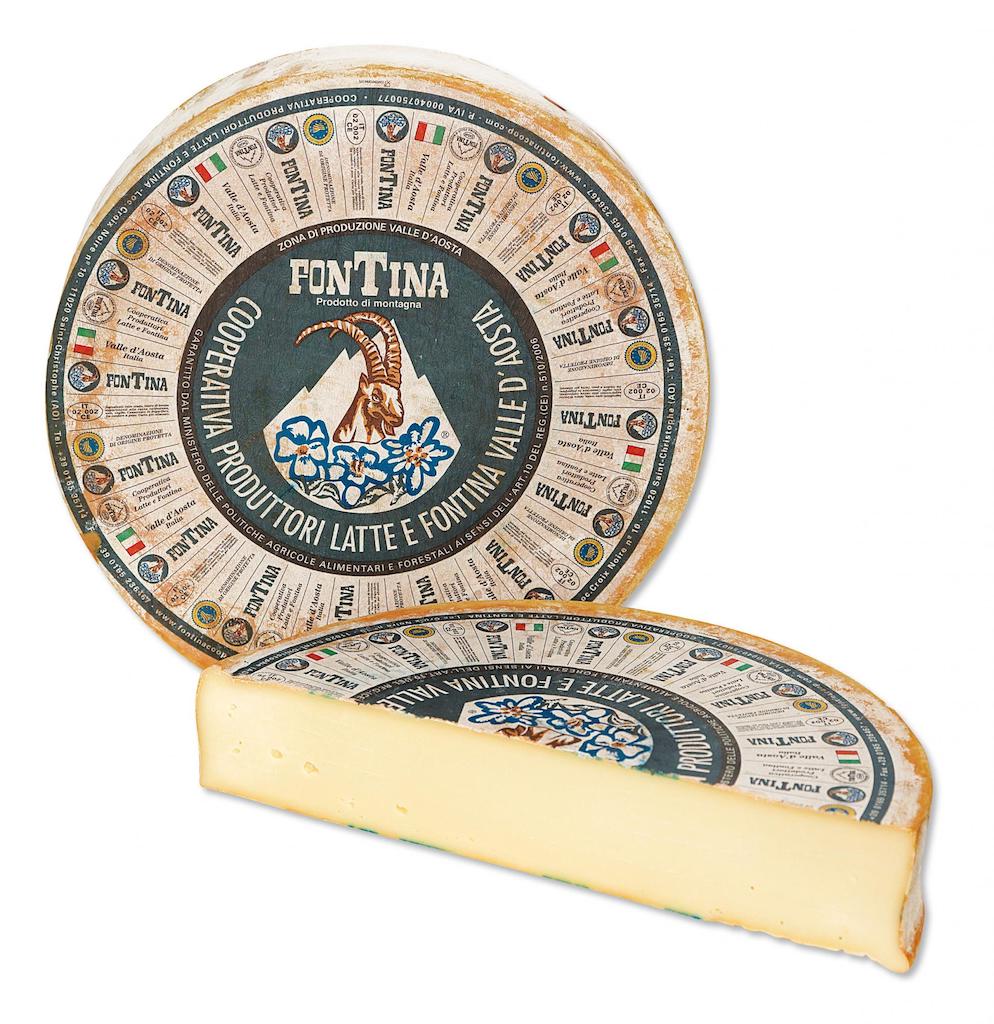

- The physical shape must be a flattened cylindrical, with flat faces, and sides originally concave, but not always detectable when ripe. The diameter must be between 35-45 cm, the height between 7-10 cm, and it must weight between 7.5-12 kg.

- The crust must be compact, light to dark brown in colour depending on the ripening conditions and length of maturation. It must be soft or semi-hard as the seasoning continues.

- The cheese must be elastic and soft dependent upon aging, and the colour can be variable from ivory to more or less intense straw yellow.

- The percentage of fat must be at least 45% of the dry substance.

- The cheese should melt in the mouth and have a characteristic sweet and delicate flavour, more intense as it ages.

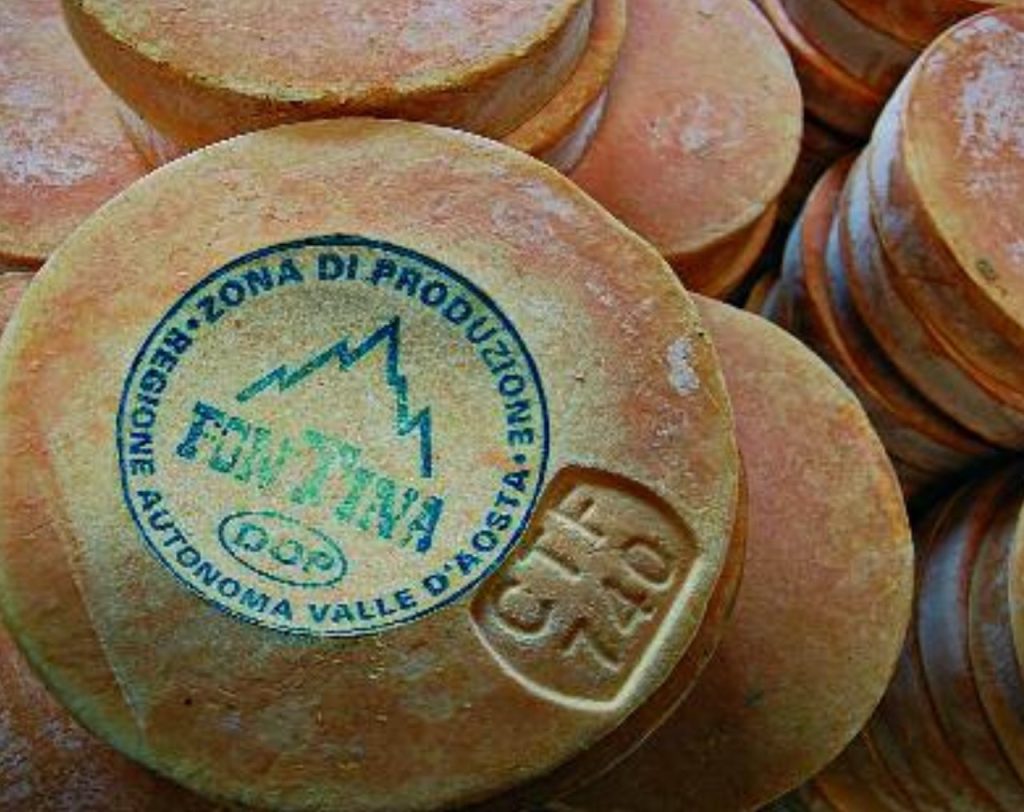

Fontina is available rindless as well as with its tan/orange/brown rind. The supple interior is ivory to pale gold and dotted with tiny holes, similar to Swiss cheese. Typically aged about 90 days, Fontina cheese becomes firmer, more robust and nuttier if aged longer. While its texture is still supple when matured more than 90 days, these older Fontinas are, in fact, considered to be hard cheeses. True Italian Fontina has a Designation of Origin seal on the wheel, with an image of the Matterhorn and the word “Fontina” stamped on it.

Fontina is in fact not protected, and today, Fontina is also produced in France, Sweden, Canada, Denmark, and the United States (especially Wisconsin). For example, both Swedish-style and Danish Fontinas are slightly tart and nutty yet still mild and earthy, but can be quite sharp depending on age. But since the Danish is generally not aged as long, it tends to be milder and creamier.

Fontina makes an excellent table cheese and cooking cheese. And soft, young Fontina makes a stellar fondue, where the Italian version of fondue (which is called fonduta) is made with Fontina, white truffles, eggs, milk, and white wine.

Identification (identificazione del prodotto)

Traceability is provided by the casein plaque and the identifier «Consorzio Tutela Fontina» (with acronym «CTF»). The casein plate bears an alphanumeric code identifying the wheel and is located on the side of the wheel. This plate is cylindrical and has a diameter of about 5 cm. The molds of the «Consorzio Tutela Fontina» identifiers (with the acronym CTF) also bear a numerical code identifying the producer. The moulds are made of plastic material and have a rectangular shape (10 x 7.5 cm) and are applied to one of the flat faces of the wheel during pressing, after which they are removed.

The molds described above are distributed by the Consortium to all entitled subjects. The trademark is imprinted on wheels having the defined characteristics and at least 80 days of maturation starting from the day of production after the check with a positive result carried out by the control laboratories.

To improve the visibility of the shape at the time of sale, the producer must affix the wrapping tissue.

The tissue paper must be placed on the face of the form that does not have the brand and must comply with the established graphic standards. The tissue paper, circular in shape, is divided into 5 main parts, namely:

- the external sunburst, containing the manufacturer’s information

- the “slices” section in which the indications on the production area alternate with the PDO mark, the word “Fontina” with the producer’s mark and the ingredients with the EEC mark and the producer’s code (6 spicchi)

- the internal sunburst with reference to the production area

- the central space with the word «Fontina» and the stylized mountain which recall the official brand of the DOP Fontina

- the space managed by the producer and/or maturer.

Reminder

Fontina is just one product from the Valle d’Aosta, and it’s important to not forget the many other products for which the valley is also famous.

This includes formaggi di capra e pecora o misti (cheese from goats and sheep), Reblec (a fresh cheese), Brossa (cream obtained from whey), Séras (a type of ricotta), Motsetta (cold cut of beef, goat, chamois, venison or wild boar), Boudin e Saouseusse (two types of sausage), I teuteun (cow udder), Jambon alla brace di Saint-Oyen (lightly smoked cooked ham), Mele (apples), Pane nero (black bread from rye and wheat flour), Tegole (very thin biscuits), Miele (honey), Grappa e Genepì della Valle d’Aosta, and last but not least vini valdostani (local wines).

References

Francesco Mathiou “La Fontina – dove e come nasce“