In early 2024 I decided to take a cruise to the Antarctic. Obviously I started with a basic planning outline, and then booked a November-December cruise, and added a few days to visit Buenos Aires, etc. I’ve summarised my planning in a separate post “Antarctic – Planning a Visit”.

In June 2024 I started to look at a packing list, and that’s when I realised that it was not a simple problem of throwing a few clothes into a suitcase.

This post is focussed only on my Antarctic packing list, i.e. the essential clothes and accessories needed for venturing into sub-zero temperatures.

I do mention, albeit incompletely, some elements of cruise dress code, and some tourist clothes for visiting Buenos Aires.

So the first thing was to understand what I would need so that I could walk out on snow in potentially sub-zero temperatures, and get back onboard alive and kicking.

Second I would need to look at what I already had, and last but not least, I would have to buy the stuff I didn’t have.

Remember that there are websites such as Cruise Critic, CruiseMapper, and Shipmate, and there are some useful videos on YouTube (e.g. Antarctica Cruise on Ponant Le Lyrial with Abercrombie and Kent and Life on Board Le Lyrial). There are even playlists such as Ponant’s Le Boreal Antarctica Cruise, which includes 25 videos.

Packing for the Antarctic is not as simple as it sounds

Thick woollen sweaters and hats, leather boots, and a Burberry jacket. Today this might seem like a fashion statement, but they were used by some of the earliest polar explorers. Things have certainly changed.

What to pack is extra important for a trip to the Antarctic. Temperatures in November-December in Buenos Aires will vary from 18°C up to 28°C, whereas temperatures in the Antarctic are likely to be between -4°C and 0°C, and on ship it will be “comfortable” or even warm.

It’s worth remembering that between -4°C and 0°C is a likely average, however it can drop to -15°C, but won’t go much above 0°C.

An additional constraint was that on the (economy) flight to/from Ushuaia passengers were limited to one checked bag (max 23kg) and one carry-on (max 5kg).

Working through the list of necessary Antarctic clothes, there is not much space (or weight) left for onboard clothes. So it looked as if weight was the key factor.

As a starting point I looked at “The secret of keeping warm in the Antarctic?” from the Guardian (2013), and the Seaborne “What to wear on an Antarctic expedition” in the Telegraph (2022). It’s good to read some general background before sitting down to study in detail clothing options, packing lists, etc.

To hammer home what I had to focus on, I’ve copied here the entry on polar clothing from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

For polar clothing to work effectively it must:

- Keep the body warm, especially fingers and toes to avoid cold injury

- Allow perspiration to disperse

- Allow free movement

- Be comfortable whatever the weather

- protection from environmental challenges (from crush to cold injuries)

Experience has shown that the “layer method” is the best way of achieving these needs over the range of environmental conditions in which BAS operates. The sub-Antarctic is cool and wet whilst the Antarctic continent is drier and very cold. In most circumstances several layers of lightweight clothes are better than one or two layers of thick, heavy clothes. The layers allow good ventilation, and at the same time the trapped air acts as good insulation against the cold.

The number of layers can be adjusted according to how cold the temperature is and the activity of the wearer.

Footwear epitomises the variety of Antarctic activities and conditions. Double insulated mountaineering boots are used for skiing and work on rock. Knee-length “mukluks” provide very high thermal insulation in a layered range of materials that are efficient only when used on cold dry snow and which require drying out overnight, often in the apex of your tent. Safety work boots are used around the stations and on Polar vessels.

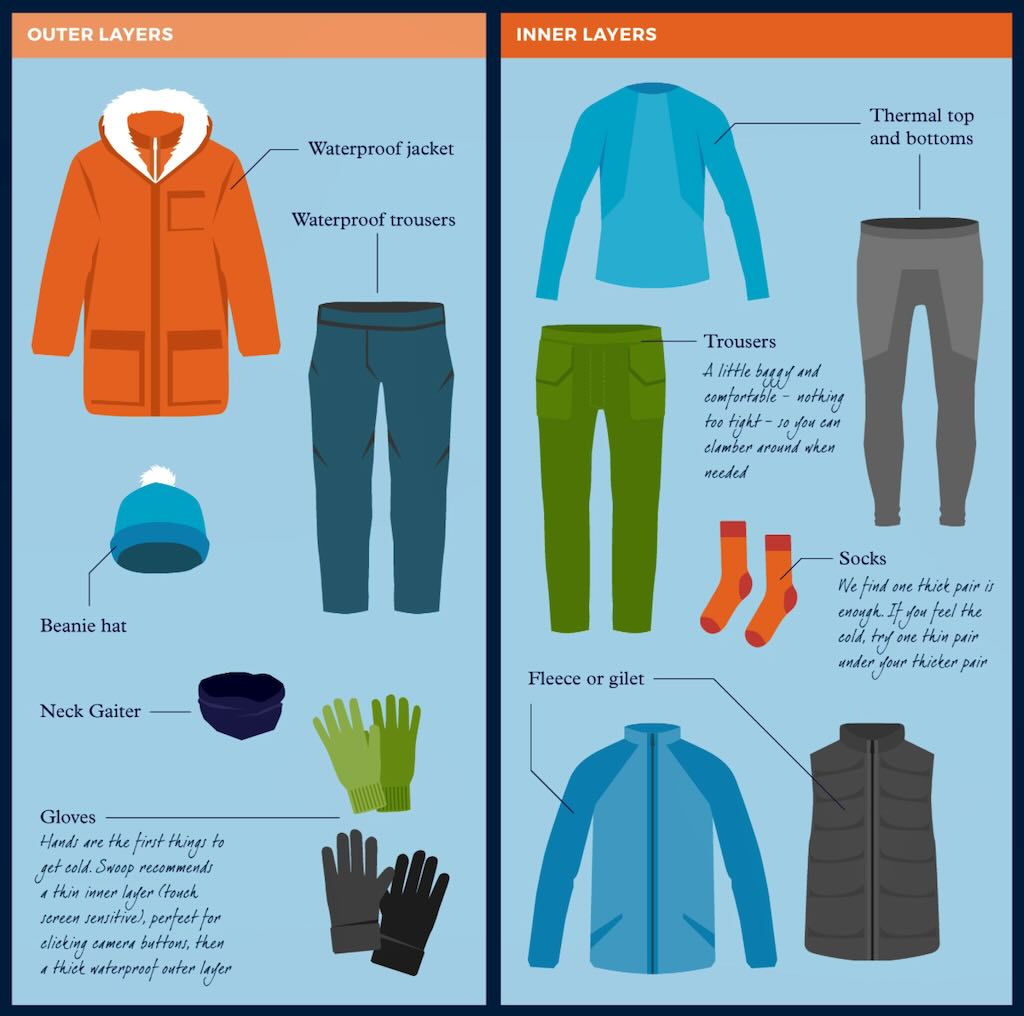

And below is what all this looks like in real life.

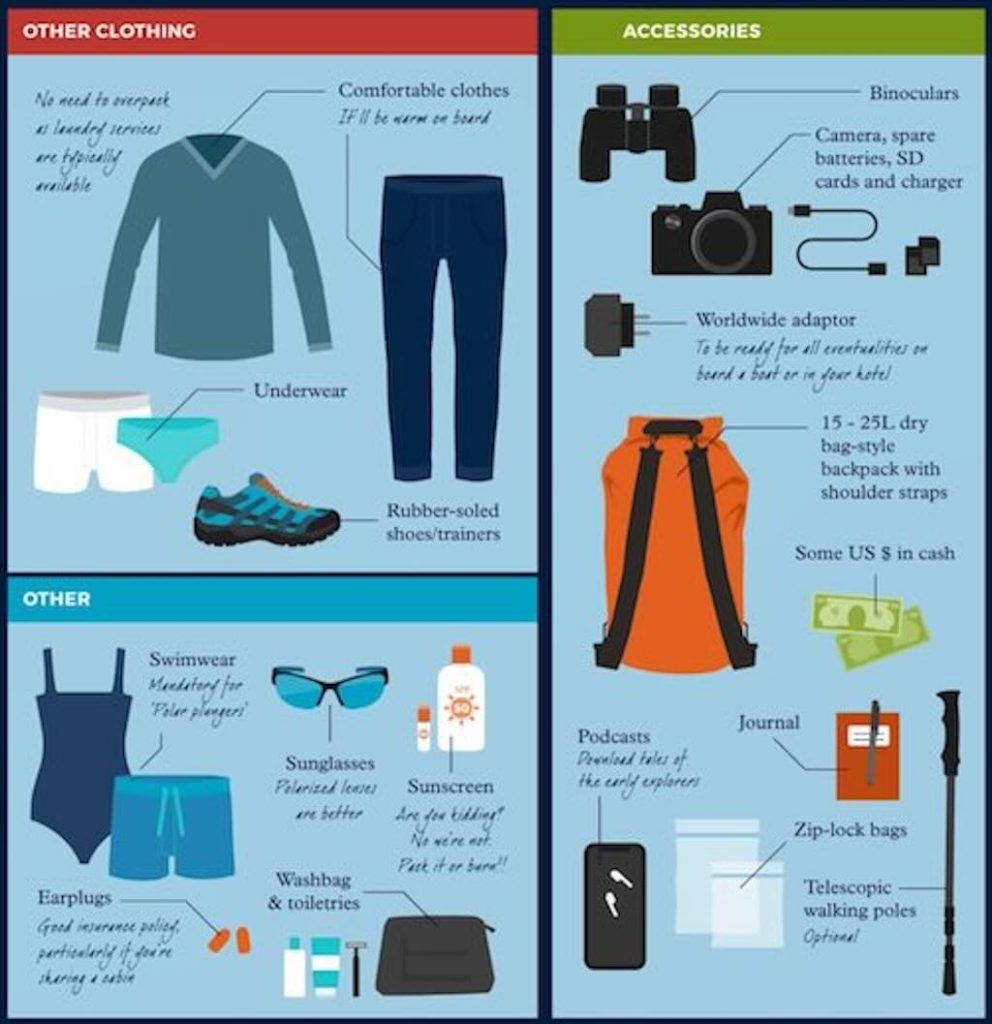

A few weeks before departure my cruise company sent me the following text and packing checklist.

Expedition programmes include activities such as zodiac outings and landings (sometimes with “wet landing”), moderate walks to more active hikes, all accompanied by your expedition team of naturalist guides.

Ports of call, visited sites, outings and landings will depend on weather conditions, position of ice, winds and the state of the sea. These can force a change of plans at any time. The Captain and the Expedition Leader may at any time cancel or stop any activity, or even modify the itinerary. The final itinerary will be confirmed by the Captain, who will take into account the touristic quality of the sites and above all, the safety of the passengers. His decision will be based on advice from experts and authorities.

Travelling to polar/isolated regions is an exhilarating experience in remote areas: please remember that you are far from modern hospitals with full medical facilities, thus evacuation is extremely expensive. Without adequate medical coverage, all expenses will have to be immediately paid with your personal funds. We urge you to subscribe to full coverage insurance, choose your insurance company very carefully, be extremely vigilant and ensure your insurance is fully comprehensive, especially if you are insured by your credit card. PONANT offers an insurance contract with extensive guarantees, please contact us for more information.

Clothing tips:

- A PONANT polar water-resistant parka is offered on board for all departures with an expedition programme (no children sizes, in case of consecutive cruises, only one complimentary parka).

- Half calf rubber boots with non-slip soles, which will allow you to go ashore in 20 cm of cold water, keeping your feet dry for walks and visits on steep paths. Boot rental will be offered onboard (for adults only) on Expedition cruises.

- Comfortable trousers: classic Winter trousers, warm cotton tracksuit, wool leggings

- Waterproof and windproof over-trousers – MANDATORY

- Winter trousers with waterproof over trousers are the ideal combination: water-resistance and comfort of trousers are essential

- Pullover, sweat-shirt or fleece jacket

- Woollen or thermolactyl Thermal underwear

- A warm hat, woollen ear muffs or fleece ear muffs, fleece or woollen neck warmer (avoid scarves that do not stay in place) – MANDATORY

- Wool or silk glove liners, water-resistant and supple gloves

- Thick warm socks (ideally woollen)

Accessories:

- Small waterproof backpack (to protect your camera from water).

- Binoculars (strongly recommended for wildlife viewing).

- Highly protective sunglasses.

- Walking poles (highly recommended).

Ideal clothes for life on board:

During the days spent on board, you are advised to wear comfortable clothes or casual outfits. The entire ship is air-conditioned, so a light sweater, a light jacket or a shawl may be necessary. When moving about in the public areas of the ship and the decks, light but comfortable shoes are recommended.

Informal evening:

In the evening, you are advised to wear smart-casual attire, especially when dining in our restaurants where wearing shorts and T-shirts is not allowed.

For women:

- Simple dress

- Skirt or trousers

- Blouse

- Polo

For men:

Officer’s evening:

For all cruises longer than 8 nights, an Officer’s Evening with a white dress code may be organized. Therefore, we encourage you to bring a stylish white outfit for the occasion (otherwise black and white).

Gala evening:

During the cruise, two gala evenings will be organised on board. Thus, we recommend that you bring one or two formal outfits.

For women:

- Cocktail attire

- Evening dress (if you wish to)

For men:

- Dark suit

- Tie recommended, possibly bow tie (if you wish to)

Shop:

A small shop is available on board offering a wide range of outfits, jewellery, leather goods and many accessories.

A laundry service (washing/ironing) is available on board, but unfortunately there are no dry cleaning services. For safety reasons, your cabin is not equipped with an iron.

Advice:

- Wool or thermolactyl technical underwear

- Polar or technical jacket

- Polar sweater or sweatshirt

- Silk or wool glove liners

- Wool leggings

- Warm hiking socks

WATERPROOF OUTER LAYER:

- Waterproof over-trousers – Mandatory

- Waterproof parka – Offered on board (not available in children’s sizes)

- A warm woollen hat covering your ears

- Polar or woollen neck warmer

- Waterproof technical gloves

HEALTH CARE:

- Sunscreen

- Lip protection balm

- Medications and prescriptions

OUTFITS ON BOARD:

- Casual outfits for the day

- Smarter outfits for dinners

- Elegant outfits for Gala evenings

- White or black and white outfit

ACCESSORIES:

- Highly protective sunglasses

- Binoculars

- Walking poles

- Small waterproof backpack

- Swimsuit (for the spa on board)

- Gym wear (fitness)

- Battery charger and memory cards for your camera

- Mobile phone charger

So what is the ideal Antarctic packing list?

Before receiving the above email for PONANT I had started to create a bullet list, but I actually preferred to backtrack and adopt a more paragraph-style description that went beyond just a shopping list. I started with a very useful overview provided by antarcticguide. To this I’ve tried to add additional detail and comments.

The email from PONANT was useful, and in particular it underlined what was MANDATORY. But there were two problems. Firstly, it could have done a little more to describe better some of those MANDATORY items. Secondly, it did not suggest any numbers. Yes, I need warm socks, but how many pairs is reasonable?

The main problem I saw with the PONANT list was that for the flight to Ushuaia there was a one luggage rule with a weight limit of 23kg, plus 5kg hand luggage.

So my plan was to pack what I needed for the cold weather, and see what space-and-weight I had left. And if that meant not doing the Officers and Gala evenings, so be it.

The below graphic was my starting point.

What does wicking mean?

In most of the Antarctic packing list descriptions, there is a constant mention of wicking materials.

A moisture-wicking fabric has two jobs. The first is to not absorb moisture, but to quickly move (or wick) sweat to the fabric’s outer surface. The second job is that when the moisture has moved to the surface of the material, and when exposed to air, it will dry faster than standard fabrics like cotton.

Moisture-wicking does not mean it will help a person sweat less, it means that when they sweat, the moisture will move through the material to the surface, and it will dissipate faster than with a “normal” fabric.

Generally this means that the material is synthetic like Nylon or polyester. There are some natural fibres that are moisture-wicking, such as merino wool.

There is a lot written about how different fabrics absorb moisture. But just how much water will different fabrics retain when wet? Cotton will retain around 8.5% water by weight as compared to its dry weight (this is the so-called moisture regain value). For 50/50 cotton-polyester its 4.45%, for Nylon its 4% and for polyester its 0.4%. The reason why cotton is bad, is that cellulose has a strong affinity for water (see this description). Wool, especially merino wool, has excellent moisture-wicking properties. It’s unusual in that wool fibres will absorb water on the inside but repel water on the outside due to the presence of lanolin, a waxy substance secreted by the sheep’s sebaceous glands, which makes their coats repel water.

The next step is to weave the strands of yarn so that they do not fit snugly. Permeability is a measure of a fabric’s ability to transport moisture through itself, determined by the sizes of spaces within the fabric. The tighter the fabric is connected, the smaller the gaps liquids have to move through, and thus won’t move through the fabric as quickly or easily as looser or more sheer fabrics. So the key is the space between the strands. These little spaces create micropores, which are just the right size to facilitate capillary action. Moisture can freely travel through these pores to the outer surface, where it can evaporate (remember it’s the evaporation of sweat that cools). Since evaporation is endothermic, it must absorb energy. When liquid water vaporizes, hydrogen bonds are broken, and breaking bonds always requires an input of energy. This energy is drawn from the persons body, and the result is a cooling down.

Polyester is the most used synthetic fibre, making up about 90% of all synthetic fibres produced worldwide. Then we have Nylon, Acrylic, Spandex (Lycra), Rayon, Olefin fibre, Microfibre, and finally Fleece.

Polyester is a synthetic blend that is one of the most reliable moisture-wicking fabrics available. To get the best results, however, polyester should be blended with other materials to create clothes that are lightweight, breathable, and moisture-wicking. The only downside is that odours tend to linger if the wearer sweats all day in it.

Polypropylene is a thermoplastic polymer much like polyester, and is an effective wicking fabric that, unlike polyester, is capable of drying quickly. Furthermore, rather than being ideal for light athletic wear, polypropylene is regarded for its thermal properties and thus is ideal for clothing that retains heat when in colder climates. Unfortunately, while an effective fabric for winter wear, polypropylene is not the most comfortable fabric to wear.

Wool is a fibre that has proven to be a great moisture-wicking fabric. Unlike polypropylene, wool is both a wicking fabric and much softer and more comfortable to wear against the skin. The compromise with this, as opposed to synthetic fabrics, is that wool is simply not as durable.

Named after the sheep the wool is cut from, merino wool is naturally thinner and softer than regular wool. It also possesses the unique trait of naturally absorbing odour caused by bacteria, thus trapping the smell and preventing it from building up for much longer than other fabrics. Many reports consider merino wool the “gold standard” for the base or foundation layer. It’s not the budget option but it does deliver on performance.

With merino wool the story does not stop there, because many clothes companies promote PETA Approved, Cruelty Free, RWS (Responsible Wool Standard), Mulesing free, etc., so it’s not sufficient to simply buy merino wool garments.

Nylon is a stretchy and light fabric that is another popular material in the world of workout wear. This is the direct answer to polypropylene by being able to dry out just as quickly but lacks the thermal properties that would constrict the fabric to winter-wear solely. As an additional bonus, nylon is especially effective at resisting mildew.

Spandex, also known as Lycra, is typically used because of its ability to stretch and retain its shape. Although maybe not the perfect moisture-wicking fabric, it provides a balance between moisture-wicking and breathability that provides comfortable athletic clothing.

Avoid cotton since it is the least moisture-wicking material on the market, yet is one of the most common materials for clothes. Cotton is easily saturated with sweat and is incapable of drying quickly.

Often some garments are also considered breathable, which means that it allows air to pass through to prevent the air closest to the body from being trapped, getting too hot, and causing more sweat. However a breathable fabric does not mean a wicking fabric, they are two different features.

Any garment that does not absorb moisture can be considered moisture-wicking, so it’s important to find clothes that are also breathable. And just because a fabric is breathable, does not mean that it is quick-drying. The key is to find a garment that is made from a good quality fibre that feels light to the touch, soft on the body, and combines the right amount of moisture management to be effective and comfortable.

It’s important to be able to add and remove a layer, but it only works if each layer is made of a high-wicking material that allows moisture to pass from one layer to the next. Layers should not be too tight nor too loose, just snugly comfortable. Cotton should be avoided as it is hydrophilic, which means that moisture struggles to pass through it and this stops the wicking process. However, cotton is fine when on-board, as cruise ships are usually warm. The key is to focus on layers and waterproof essentials. Another focus is on light-weight durable multi-use materials.

Some experts suggest to look for materials that blend cotton and moisture wicking polyesters. The cotton component makes the T-shirts feel softer and breathe better. Combined with the polyester fibres, these shirts will also wick moisture away and help dry faster than a classic T-shirt when sweating.

What is fleece?

Background reading about visiting the Antarctic immediately brings up the issue of warm clothings. And with that comes two specialist words, wicking and fleece. Above we delved into the special world of wicking materials, but what exactly is a fleece.

Wikipedia mentions fleece as being the woollen coat of a domestic sheep or long-haired goat (Angora comes to mind), especially after being shorn. And Wikipedia also mentions the polar fleece, a type of polyester fabric often used in jackets. The Wikipedia article on polar fleece is worth a read, but the essential element is that it’s a light, strong synthetic pile fabric that mimics, and in some ways surpasses, wool. Fleece can range from being high loft to tightly knit, with high loft fleece being warmer. Also fleece is machine washable and dries quickly. But fleece is not waterproof and will lose most of its insulating quality when wet, nor is it windproof. But because fleece is hydrophobic, it is a good wicking material.

Because fleece traps tiny air pockets which holds body heat, it is usually seen as an excellent mid-layer. Fleece is defined by its weight, and ranges from <100 gsm (grams per square meter) for summer walking in cool weather, to >300 gsm for Artic/Antarctic thermal fleece (200-300 gsm is also good for a mid-layer). Obviously a lighter weight fleece is thinner and easier to pack, and a polar fleece is thicker. This website has a decent description of around 10 different types of fleece, from cotton-blended to French Terry.

So lets start with the layering system

The PONANT list mentioned “insulate base layer” and “waterproof outer layer”, but many, if not most, of the “pro” websites mentioned a three-layer clothing system.

It’s true that cruise trips don’t usually see much intensely cold weather, with average temperatures usually just below freezing. So it’s not totally illogical to stress just two layers, e.g. a good (merino) wool base (wool is good for breathability and moisture wicking) and a windproof/waterproof outer layer (rain pants and parka). Some people suggested casual fleece pants when it’s cold and just the base and rain pants the rest of the time. A few sweaters or fleece tops were considered a good option. However the coldest conditions are typically on the long scenic zodiac trips and landings, where people are sitting on open water with limited movement and there’s a constant cold breeze.

For a cruise to Antarctica, the advice is to take a variety of clothes that will keep the body comfortable, warm and dry, while dealing with potentially harsh weather conditions. The key is layering, as this will help regulate body temperature and provide protection from wind, moisture, and cold.

Layering System

Antarctic conditions require the three-layer clothing system:-

- Base/Foundation Layer (Moisture-Wicking)

- Mid Layer (Insulation)

- Outer Layer (Waterproof/Protection)

1. Base Layer (Moisture-Wicking)

- Purpose: Wicks moisture away keeping skin dry and warm.

- Thermal Underwear (Top and Bottom): Choose merino wool or synthetic moisture-wicking material. Bring two or three sets for rotating.

- Socks: Several pairs of moisture-wicking, thermal socks (wool or synthetic). Wool socks are excellent for warmth and comfort. Bring enough pairs to rotate daily.

This lightweight “next-to-skin” base layer is most useful for really cold days (not needed onboard). Names that often appeared were Helly Hanson base layers, Smartwool Lightweight Base Layers or Icebreaker Oasis Base Layers. The best is made from 100% merino wool, which is the best high-wicking wool available. Focus on comfort, quality and good moisture control. An alternative to wool could be Patagonia Capilene Lightweight Base Layers. For a standard 2 week trip, three pairs of top and bottom base layers were considered enough (using the onboard washing services).

2. Mid Layer (Insulation)

- Purpose: Provides insulation to trap heat close to the body.

- Fleece Jacket or Sweater: A warm, lightweight fleece layer is essential for trapping heat. Have two options to alternate.

- Fleece or Wool Pants: To wear over the base layer, insulated pants help provide warmth during excursions.

- Insulated Vest: Optional but can add extra warmth without too much bulk.

- Sweaters: Wool or fleece sweaters can also work as mid-layers. Bring one or two.

Then comes shirts, up to 5 either long-sleeve or short-sleeve shirts, depending upon using onboard washing services. The ideal fabric is a lightweight, breathable and super quick-drying polyester, nylon or merino wool. Avoid cotton as it holds moisture and is slow drying. Craghoppers, Icebreaker, and Columbia were often mentioned.

Ideally at least two pairs of trousers, which must be warm, but comfortable. Orvis moleskin pants or Canterbury of New Zealand were often mentioned. For those colder days, go for a pair of trousers that are thick, warm and waterproof. Pairs from North Face and Helly Hanson were mentioned as lightweight and manoeuvrable. Ski trousers were not recommended, but if used they need a good inner base layer.

For cold climates like Antarctica, an insulation fleece layer is very important. A single mid-weight fleece, jacket or parka top works as a second layer and is used to go over a base layer, but on slightly warmer day, can be a standalone layer that can be worn over a T-shirt. Insulation fleeces that use something like Polartec materials were mentioned as an excellent option. Typically, Polartec fleeces come in 100s, 200s or 300s. 300 is the heaviest, but usually the best weight in the cold Antarctica conditions. Polartec-200 Fleece Jackets include North Face, Helly Hansen and Columbia were often mentioned.

A really useful feature to look out for when buying a fleece jacket is a hood as this can double as an instant balaclava in the cold, biting wind. Arc’teryx Fortrez Hoody or the Fjallraven Ovik Fleece were mentioned.

3. Outer Layer (Waterproof/Protection)

- Purpose: Protects from wind, rain, and snow, keeping the body dry.

- Waterproof, Windproof Jacket (Parkas): Most cruises, including PONENT, provide an insulated, waterproof parka for land excursions. But in any case a heavy-duty waterproof and windproof jacket is essential, and ideally it should have a hood.

- Waterproof Pants: Bring waterproof overpants or ski pants to wear over the mid-layer. Literally everyone, including PONANT, considers these waterproof and windproof over-trousers MANDATORY. GoreTex is often mentioned, and many stress picking a lightweight breathable option.

A PONANT polar water-resistant parka is offered on board for all departures with an expedition programme. I understood that the parka was water and wind resistant, but not insulated against the cold, so a light-wight down-plume jacket was also recommended by some people.

Generally the outer core shell layer or “third layer” should be a waterproof, windproof and warm shell jacket and trousers. Warm jackets can be very complex, but there are two general types, either synthetic or down (some are also insulated with wool). The upside of down jackets is that they are usually far lighter and generally warmer than synthetic jackets. However, because of this they are a great deal more expensive! Down jackets are also not particularly good in wet or moist conditions.

Remember weather proof or water resistant does NOT mean waterproof.

The crucial factors to consider when selecting an outer jacket are:-

Warmth and Weight: The weight of an outer jacket can vary considerably from very light (around 450 grams or less) to more than 1kg. The lightest winter jackets on the market use a down fill and often weigh as little as 200 grams. Down is ideal in that it provides the best weight-to-warmth ratio available. However the Antarctic is cold and the light-weight jackets won’t be good enough. Although often slightly more cumbersome, a jacket on the heavy side will be the warmest, so aim for a winter jacket in the region of 700-950 grams for the Antarctica.

Waterproofing: Despite down jackets being dominant in terms of warmth, they are far more susceptible to rain and moisture. When moisture enters a down jacket the jacket will lose its insulation capacities. A down jacket will not break down at the slightest hint of water, however, in a heavy downpour a synthetic jacket will keep dry. Overall down is the best option for Antarctica, so the crucial factor to look out for is a jacket with a solid water-resistant outer fabric layer. Generally one of the best fabrics on a down jacket is Pertex Shield, and for a synthetic jacket it’s Nylon. The best jacket on the market is probably the Fjallraven Expedition Parka, or possibly the North Face Himalayan Parka (both are durable and weather proof).

An alternative is a super-warm insulation layer and a thinner outer core waterproof layer such as the North Face Nuptse jacket. It’s worth noting that ski jackets are often not as warm as proper arctic jackets, but it depended on the quality (the same goes for ski trousers).

An excellent suggestion was a jacket with a hood, good hand warmer pockets, and big enough to allow easy movement.

For some people warm trekking trousers were also an option for the Antarctica. The key features were water resistant, wind resistant, sun protective, and a fleece inner material with a quick-drying polyester outer layer for warmth. Yes, I know that waterproof is better, but Arc’teryx Kappa Pants, North Face Resolve, Fjallraven and the Helly Hanson Packable pants were often mentioned.

The antarcticguide also noted that jeans are useless, since they absorb moisture quickly, are difficult to walk long distances in, take a very long time to dry, and let body heat escape. Also whilst cotton clothes are fine on board the ship, they are terrible at wicking and won’t let the body breathe.

Footwear

Opinions vary, between taking a lighter shoe for onboard, whilst others suggested taking Gore-Tex walking boots (broken in and with ankle support), which could be also worn onboard. And there is also the question about what shoes to wear during any stopover in Buenos Aires.

According to the antarcticguide, Antarctica footwear (boots and thermal socks) is just as important as clothes.

A key message is to never forget extremities, and keep head, hands and feet warm at all costs.

The first key point to note is that standard hiking boots are not suitable for Antarctic conditions. Cold weather Antarctica footwear, often called Bunny boots or Mukluks, are usually provided by the cruise operator for shore landings. Passengers only need to bring standard footwear to wear around the ship.

Proper Antarctica footwear will have very thick rubber or synthetic soles, a good layer of insulation (often removable), soft uppers and thick insulated insoles to prevent heat loss from the snow and ice. A key point here is that the boots should not be too tight as it’s the trapped air between layers that actually creates the warmth.

Socks are almost as important as the boots. On-board a medium weight sock will be fine. On excursions it is advised to wear one thin pair of comfortable liner socks underneath an outer thermal pair of hiking socks.

Make sure the thermal socks are seamless and made of a good quality wicking material (always avoid cotton). Some brands will cushion their socks, this is a personal preference. Ragg Wool is definitely the best thermal sock material. For liner socks a good material is also polypropylene as it is very good for wicking moisture. It’s recommended to bring at least 4 pairs of thermal socks and several liner socks. Often mentioned were SmartWool for thermal socks, and Bridgedale Coolmax Liners for liner socks.

Head and hands

It is extremely import to keep both hands and the head warm, and to have a good pair of sunglasses. In addition a warm pair of gloves is essential to keep the hands well insulated as they are the first things to freeze in cold conditions.

Research suggests that up to 20% of a persons body heat is lost through their head. It is therefore very important to keep the head warm. Many fleeces and jackets come with in-built hoods which is great in wet conditions and ideal for windy conditions. However, on dryer days, a beanie or headband is often a better idea as it doesn’t restrict head movement or view of the wildlife. North Face polar Beanie, Helly Hansen beanies and Mountain headwear were often mentioned. Another option is a synthetic balaclava as it shields the face from wind and can also be wrapped up to form a hat. A balaclava with a hood could be the best option, e.g.such as a Rothco synthetic balaclava. A neck gaiter or scarf is a simple option and can provide protection for the face against cold wind.

Warm gloves are an essential piece of clothing for any Antarctica trip. In the summer months near the peninsula a medium weight pair of gloves will be sufficient. A good option is to wear a thin liner glove with a medium weight glove or mitten.

Taking photographs it’s important to get good quality gloves which allow for more dexterity and warmth. Cheap gloves won’t have the same movement or insulation.

In terms of inner gloves (liners), look for a good quality pair with excellent dexterity and good wicking properties (allows moisture to pass through it). Synthetic and/or wool are good options. Avoid cotton inner gloves as these will restrict moisture flow. The inner gloves should have a very comfortable lining and be lightweight. Some gloves can be used with touchscreens.

It is very importance to have good quality outer gloves. A top quality outer gloves will provide excellent warmth, great waterproofing and good dexterity. The ideal glove will be comfortable, warm, waterproof and durable. Black Diamond Guide Gloves, Outdoor Research Southback Gloves or Dakine Scout were often mentioned.

Other clothing and accessories

The face is especially vulnerable to cold injury and complete face protection is essential. Try combinations of balaclava, face mask, hat, and goggles together to ensure that there are no gaps (often a crescent shape between the edge of the goggle and a face mask or balaclava is hard to cover). But breathing must be free and moisture must be able to escape so that goggles don’t fog.

The light at high latitudes (and altitudes) is usually very bright and quite dazzling, especially with the pure white reflection off snow and ice. It is possible to get snow-blindness if the eyes are not properly protected. Some people recommend full snow goggles instead of sunglasses as these protect your eyes a little better. However, polar sunglasses are far less cumbersome.

What’s important is that sunglasses should have dark coloured lenses and full side coverage. This can be sunglasses with side-flaps (mountaineering or glacier glasses) or sport sunglasses with big lenses, wide sides, and a contoured shape that prevents light from entering at the sides. Non wraparound sunglasses provide little or no protection from peripherally focused UV radiation. Also avoid metal frames as they can freeze to the skin, and bring a hard case to protect the sunglasses in the luggage.

Most websites mention that it’s important to aim for 100% protection from ultraviolet (UV) A (soft), B (intermediate) and C (hard) rays. Of the ultraviolet radiation that reaches the Earth’s surface, more than 95% is the longer wavelengths of UVA, with the small remainder UVB. The reality is that almost no UVC reaches the Earth’s surface. The fraction of UVA and UVB which remains in UV radiation after passing through the atmosphere is heavily dependent on cloud cover and atmospheric conditions. On “partly cloudy” days, patches of blue sky showing between clouds are also sources of (scattered) UVA and UVB. During total overcast weather, the amount of absorption due to clouds is heavily dependent on the thickness of the clouds and latitude, with no clear measurements correlating specific thickness and absorption of UVA and UVB.

UV protection has a rating system, from 0 for very lightly tinted fashion lenses, to 4 for very dark lenses that filter out more than 92% of UV light (3 is for standard sun protection).

What to do with prescription glasses?

Instead of ordering new snow glasses with prescription lenses, it’s possible to find both sunglasses and snow goggles that fit over prescription glasses.

I have a pair of Alba Optics sunglasses which could fit over some simple frame prescription glasses, but would not be perfect. Interestingly this company provides an “optical clip” that could be fitted with prescription lenses by someone’s “trusted” local optician, which then bond inside the sunglasses. If you can plan ahead then this might be a good option.

I also have a pair of uvex downhill 2100 CV planet goggles which are big enough to fit over prescription lenses in a simple frame. I have the mirror blue S2 colourvision single spheric lens, with an antifog coating. This manufacturer also makes goggle frames with interchangeable lenses.

Mirrored lenses are best for bright light and reduce eye strain. It would appear that everyone’s eyes respond differently to different colour goggle lenses, and some people prefer one colour over another. A blue, green or red tint covers a range of conditions, from partly cloudy to partly sunny.

Reading around the subject it looks like many people on Antarctic cruises just used their normal prescription polarised wraparound sunglasses, but also took snow goggles with them for the trips in the zodiac. Also it was recommended to attach a safety to glasses, because they could be blown off in strong winds.

Many people commented on the need to wear skin protection on the cheeks and nose. It’s easy to get burnt with just 2 hours in the sun. Bring a high-SPF sunscreen for face and lips.

And what about a camera?

Everyone will have a camera, some people will have a sophisticated DSLR with a telephoto lens, others will have a point-and-shoot, and others might just use their iPhone camera.

Today I’m only interested in taking some decent quality “tourist” photos of my trips, and my old SLR now just sits on the shelf along with my collection of other antique cameras. The latest iPhones have very good camera functions, but we have become so dependent upon them for payments, etc., that I prefer not to risk it being stolen, damaged or lost. So recently I have resurrected my old 20 mega-pixel Sony Cyber-shot with its x8 optical zoom and a 64 GB card.

Perhaps the most important thing is to protect the camera from snow, rain and spray, and a simple zip-loc plastic bag is perfect for that. Condensation in the cold weather can be a big problem. When there is a quick change in temperature, the front of the lens can often fog up with condensation. This frequently happens after taking pictures outside and then coming back inside. To combat this put the camera in an air-tight bag before coming back inside. This allows the camera to slowly adjust to the new temperature and prevents condensation from forming.

Another thought is to have gloves (and/or glove liners) that allow some form of camera control. Ski gloves or mittens are often quite stiff, and it’s difficult or impossible to take photos with them on. There are gloves and glove liners with finger tips that allow touch-screen use.

Finally it’s worth remembering that in the cold, battery life will be shorter, so an extra battery and memory card might be a useful addition (memory cards frequently malfunction). One other suggestion was to have the possibly to write and read a USB stick so photos can be shared with other passengers.

And binoculars?

Everyone will also have binoculars, but what’s the best ones to have on an Antarctic cruise?

I carry a pair of Pentax Papilio 8.5×21 in the car, but are they the right ones for a trip to the Antarctic? Firstly are they fog and waterproof (or at least water resistant)? Can the focus wheel be used with gloves? Can they be used with sun glasses? What magnification, and what weight? And what are the alternatives, remembering that prices for a pair of binoculars can range from $150 to $3,000.

Firstly we can eliminate my Pentax binoculars because they are more suited to observing insects, flowers and objects in museums, and not distant penguins on snow. These are great when you know what you want to look at, and it’s not that far away. And this is evidenced in the 8.5×21, which means a good magnification of 8.5 but objective lens diameter of only 21 mm. So they are not that good for scanning a scene some distance away, and furthermore they don’t capture that much light from distant objects.

I also have a pair of Nikon Prostaff P3 8×42. So again these have the same magnification as the Papilio. An interesting way to consider magnification is that x8 means that something at 80 metres will appear as if it were at 10 metres when viewed with the naked eye. The big difference is in the objective lens diameter (42 as compared to 21), which is all about capturing more light, but it also makes these binoculars heavier.

As far as I can tell, most experts suggest that a good pair of 8×42 or 10×42 will be the best for an Antarctic cruise, with the additional criteria that they are easy to use with gloves. So the Prostaff P3 is a solid choice, good magnification and field of view, easy to grip and use, waterproof, and not too expensive.

Folding trekking poles

In the Ponant list its mentions “walking poles (highly recommended)”.

I guess this means “folding” poles, and my understanding is that walking poles can just mean a pair of walking sticks, or it might suggest Nordic type poles specifically designed for walking that uses the persons entire body and requires a specific technique.

I presume that what is really meant is trekking poles which are adjustable in length, have a comfortable grip, and interchangeable tips for optimal grip on snow and ice.

I have a few different types of poles, but what’s perhaps most important is that the poles can be folded and go into the suitcase. I took Glymnis folding trekking poles, which are only around 36 cm long when folded and fit quite easy in any mid-sized suitcase.

And finally a backpack

Some suggestions for onboard

Here we just collect some of the suggestions made about clothing and accessories, etc. for onboard. It is certainly not complete, but just a reminder. And in some cases I’m not sure what the objective is, but it’s still useful to point to clothing and accessories options worth considering.

- Comfortable clothes, long-sleeved shorts, jeans or trousers, and light sweaters.

- Travel in lightweight sports trousers, T-shirt, light-weight vest.

- Comfy, closed toed, easy to slip on shoes for wearing around the ship. Should be comfortable and have soles with good grip so they can be worn on deck. Others also mentioned comfortable shoes or slip-on sneakers.

- Shorts and T-shirt for Buenos Aires.

- Light-weight trousers, or several pairs of durable and comfortable pants or leggings that can layer

- Ten pairs merino wool socks of different weights.

- A warm, waterproof jacket.

- Sleep-ware.

- Swimming/sauna trunks.

- Shower slippers.

- Sunscreen + lip screen.

- Snacks – lots of M&Ms for cabin snacks and granola bars for travel days.

- iPhone, plus second iPhone as back up camera, and always pack all electronics in waterproof bags or cases.

- Plug adaptors.

- A laptop with external hard drive.

- Toiletries (there’s lotion, shampoo and conditioner on ship), but don’t forget the travel essentials like travel sized deodorant, sun screen, lotion, hair ties, hair brush, face wipes, tampons, contact solution, toothbrush, toothpaste, hand sanitiser, masks, and ear plugs etc. Remembering to avoid single-use plastics.

- A multi-function Swiss army knife was mentioned more than once.

- Medications (including Dramamine tablets).

An interesting addition was a list things people packed, and didn’t use.

- Books/Kindle

- A Bluetooth speaker

- Laundry soap (merino wool can easily go 7-10 days without being washed)

- A day pack (not used because it was easier to go on shore without a backpack at all)

- A lightweight sweater (the ship was always warm)

- Hiking pants (not good choice).

- For the “formal” evening, some just interpreted that as having a nice shirt (or dress).

- Also when waterproof boots were provided, only lightweight shoes would be needed onboard. Here I was never sure if the boots provided were also warm, or just waterproof.

- There were some suggestions about limiting the weight. Maybe just one fleece was enough, and only one pair of the outer layer waterproof pants would be sufficient. When an outer parka was proved, only a lighter, inner insulated jacket might be enough (offering protection against wind and cold, but not being waterproof).

- Scopolamine patches – for nausea. Get a prescription for them, and they have quite a few side effects. However, they’re very useful when crossing the Drake Passage.

- Bonine – Should not be taken with the patch, but it can be taken daily instead of the patch once the Drake Passage is cleared.

- Throat lozenges – one of the biggest side effects of the nausea patch is a very dry mouth.

- Advil/Tylenol – always good to have on hand, especially for the headaches that come with the nausea meds.

- Usual medications

- Chapstick & lotion – Antarctica is in fact a desert and it is very dry, so some skin creams and lip balm are useful.

- Apparently ginger can really sooth the nausea on the journey.

SWOOP mentioned the onboard dress code leans very much towards the casual and comfortable, but if possible men should try to bring at least one shirt for the more formal moments. They also mentioned that the ships are kept warm inside, but most people keep a warm outer layer (and their camera) with them at all times. Also the laundry service on all ships is typically very efficient, but it can be a little expensive for smaller items (socks, underwear) so some guests washed these in the bathroom. Trekking poles were a good idea, and even having just one pole can be really useful as a third point of balance. They noted that walking boots were not a necessity on the Antarctic trip. Onboard closed-toe shoes with a good grip are a must, and these could be a pair of simple comfortable hiking trainers/sneakers.

And to close this “extra reading”, check out Extreme Cold Weather Clothing Antarctic Expedition Wear 2024-25 on Cool Antarctic. Read and re-read just to be sure that you have not forgotten something.

Whats did I already have?

The next step was to check out the clothes I already had in my wardrobes.

Not much is the answer, but I did have some “warmer” clothes for playing golf in winter and a few pieces from the days when I went skiing.

Going by layers, I didn’t have many “base layer” (or “foundation layer”) clothes.

My cotton underpants didn’t look to be an option, so I would need to source some cold-weather underpants.

I already had three different types of “next-to-skin” base layer in my wardrobe. I used these for winter golf. The first was a crew-neck with 93% polyester and 7% polyacrylic. The second was a polo-neck with 65% cotton, 30% polyester, and 5% elastane. The third was a crew-neck with 90% polyester and 10% elastane. Interestingly the cotton-mix polo-neck certainly weighed at least twice that of a polyester base-layer top.

I had no “next-to-skin” base layer leggings. However, I will travel with compression stockings, which are in fact very “next-to-skin”, and are made of a blend of synthetic materials such as nylon, Spandex (also known as Lycra or Elastane), or polyester.

For the “mid-layer” there is a big different between T-shirt and dress (or collar) shirts. All but one of my dress shirts had no indication of the material used. Just in one shirt, it was marked 100% cotton, but I presume that all my other shirts were also 100% cotton.

On the other hand my T-shirts were either 100% cotton, or 100% polyester, or 90% polyester mixed with 10% Spandex, or even 60% cotton with 37% polyester and 3% Spandex.

My existing casual trousers consisted of pairs with 54% polyamide, 37% cotton and 9% Elastane, or 71% polyamide and 29% Elastane, or 79% polyamide and 21% Elastane. Also I have two pairs of light-weight sports trousers, 100% polyester, and one pair with a mix of 61% wool and 39% polyester.

I often wear shorts, and again they can vary from a heavier 100% cotton, through to 100% polyester. Some shorts were made of polyester mixed with between 1% and 10% of Elastane. A few pairs of shorts were cotton mixed with 1% to 4% Elastane.

Many of my warmer clothes were designed for golf, as were my shorts and T-shirts.

For what might be called the second layer I had a wide variety of options, but none were insulation fleece.

I did have a couple of 100% polyester “second layers”, and one with 40% cotton mixed with 30% wool and 30% acrylic.

I also had “second layer” windbreakers with 100% polyester, and some of them had a 100% Nylon liner. One windbreaker pullover consisted of 50% wool and 50% acrylic.

I had three “third layer” or “outer layer” garments. One was a “cyclone” with a 100% Nylon shell coated with polyurethane, a lining of 100% Nylon and an insulation of 100% polyester. The second had a 100% polyamide shell, a second shell of 75% polyamide mixed with 25% Elastane, a lining of 100% polyester, and a filling of 90% grey duck feathers mixed with 10% goose feathers, and marked “700 Down”. The third had a 100% polyester shell, a second shell of 100% polyamide, a lining of 100% polyester, and a filling of 90% white duck feathers mixed with 10% goose feathers, but was only marked “High Quality Down”. It did appear to also have a second filling of 100% polyester.

What did I buy?

When buying, I tried to keep in mind stuff that I could wear for golf. Even an early morning start in winter needs some decent protection, so stuff like a good merino wool base layer top could be ideal.

But I had to start somewhere, so decided to start with one example of “base layer” sports underwear. Advice from different sources included Icebreaker, Helly Hansen, Smartwool, merino.tech, and Danish Endurance.

Both Icebreaker and Smartwool are US based, merino.tech is Canadian, Helly Hansen is Norwegian, and Danish Endurance is (surprise) Danish. Not living is a big city, my habit is always to turn to an online supplier. However I did find Icebreaker underwear in a local sports shop, but the range of sizes, etc. was limited (in particular in summer). It really is impossible to know what is the “best”, since they all score at least 4/5 based on 100’s of reviews. Price was not a major differentiator for sports underwear, ranging from around 28€ to 35€ per pair.

I decided to focus on natural merino wool for my layers, and I started with a pair of lightweight (165g) boxer underwear from merino.tech. I tried them out in a coolish period in early June and found them very comfortable, and not overly warm in the sense that they were very breathable. I ordered two more pairs of underwear.

My logic then lead me to buy a “next-to-skin” base layer to go over underwear. My focus was on a set, including a long-sleeved crew-neck top and leggings. For those companies that provided sets the price went up to around 100€. With other companies it was necessary to buy separately the top and leggings, and the combined price appeared to be around 140€.

I bought a mid-weight (250g) base layer set again from merino.tech, in part because it included also a pair of merino wool socks. I wore the set overnight with the window open, at a temperature of around 7-8°C, and found the base layer warm and very comfortable.

I went with the advice that for a standard 2 week trip, three underwear boxers (and hand washing), and three pairs of top and bottom base layers should be enough.

Then comes shirts, some experts mention the need for up to 5 either long-sleeve or short-sleeve shirts, depends upon using onboard washing services. The ideal fabric is a lightweight, breathable and super quick-drying polyester, nylon or merino. Avoid cotton as it holds moisture and is slow drying. I checked out Craghoppers, Icebreaker, and Columbia.

Ideally at least two pairs of trousers, which must be warm, but comfortable. I checked out Orvis moleskin pants or Canterbury of New Zealand. For those colder days, the suggestion is to go for a pair of trousers that are thick, warm and waterproof (best option ski pants). Pairs from North Face and Helly Hanson are said to be lightweight and manoeuvrable. Ski trousers will need a good inner base layer.

I decided to move the shirts and trousers from my Antarctic packing list to my on-board cruise packing list.

For cold climates like Antarctica, an insulation fleece layer is very important. A single mid-weight fleece, jacket or parka top works as a second layer and is used to go over a base layer, but on slightly warmer day, can be a standalone layer that can be worn over a T-shirt. Insulation fleeces that use something like Polartec materials are an excellent option. Typically, Polartec fleeces come in 100s, 200s or 300s. 300 is the heaviest, but usually the best weight in the cold Antarctica conditions. Polartec-200 Fleece Jackets were offered by North Face, Helly Hansen and Columbia.

The outer core shell layer or “third layer” is a waterproof, windproof and warm shell jacket and trousers. Warm jackets can be very complex, but there are two general types, either synthetic or down (some are also insulated with wool). The upside of down jackets is that they usually far lighter and generally warmer than synthetic jackets. However, because of this they are a great deal more expensive! Down jackets are also not particularly good in wet or moist conditions.

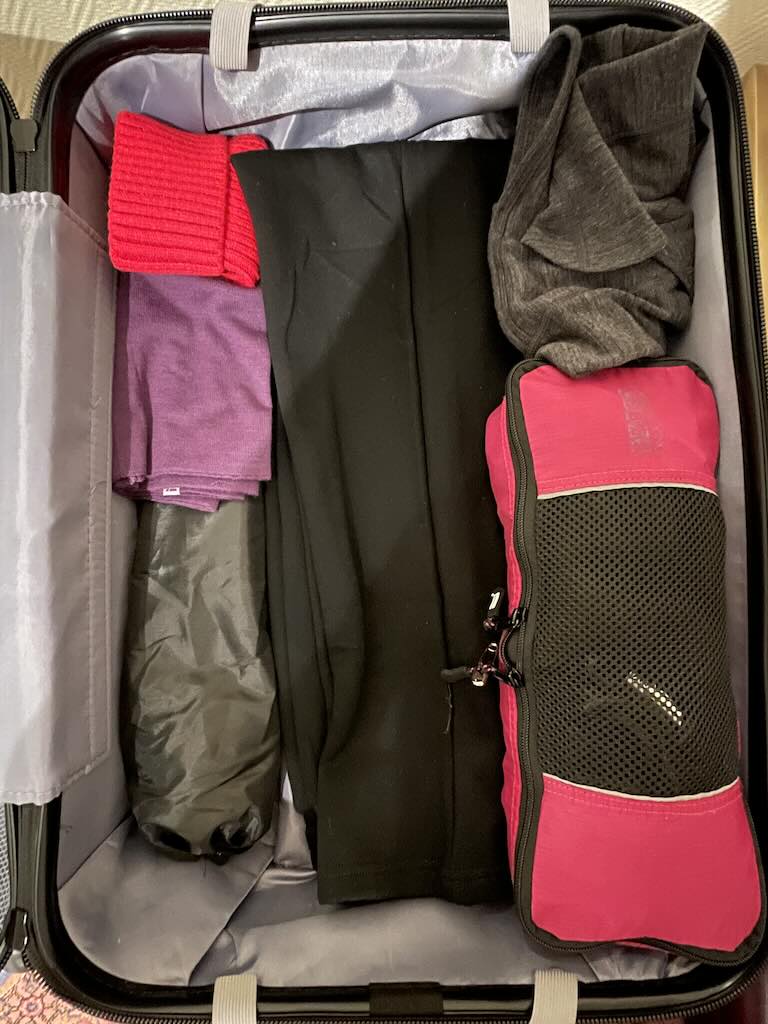

Space and weight requirements

My starting point was a medium sized hard-shell roller suitcase. Total size 55x40x25 weighting empty 3.1 kg.

I allocated the larger side of the shell (55x40x15) for Antarctic gear, and the other side (55x40x10) for cloths for my stay in Buenos Aires and for onboard the cruise ship.

Where possible I used compression bags, and arranged things so I would not have to touch the Antarctic clothes during my pre- and post-cruise visits to Buenos Aires (total 8 nights).

My short-form Antarctic packing list

This list is only for Antarctic clothes and accessories in the check-in suitcase.

- 3 merino.tech boxer underwear

- 3 merino.tech base-layer sets (top & bottom)

- 1 Mizuno polyester base-layer

- 1 mid-layer ARC’TERYX fleece top

- 1 mid-layer Derek fleece trousers

- 1 pair SprayWay Gore-Tex outer-layer “shell” waterproof trousers

- 3 pairs merino.tech base-layer socks

- 3 pairs RTZAT 90% merino wool ankle liner socks

- 1 pair TrekMates classic Dry Gloves

- 2 pair Evridwear merino wool glove liners

- 1 merino neck gaiter from Danish Endurance

- 1 Icebreaker merino balaclava

- 1 polyester-lined wool “beanie”

- 1 pair Glymnis folding trekking poles (740 gm)

- binoculars

- uvex downhill 2100 CV planet goggles

- spare prescription sunglasses

- spare prescription glasses

- 20 mega-pixel Sony Cyber-shot with its x8 optical zoom and a spare 64 GB card

- 1 450 g mid-layer Mammut “DryDown” hooded jacket (to be taken as hand luggage)

Comments after returning home

I’ve tried to assess how successful I was in packing just the right clothes and accessories for my trip to the Antarctic.

Firstly, the weather during my trip was not particularly cold, and we actually had a couple of days of really intense sunshine. But on one day the temperature did drop to -8°C, however it usually oscillated around the -4°C to +2°C.

This meant that I did not use much clothing from the so-called mid-layer. But this does not mean that I should not have taken that layer with me. The cruise previous to mine, experiences much colder and wetter conditions.

I did bring 3 complete sets of merino wool base layer. The housekeeping onboard was delivering washing on the same day, so I could easily have used just 2 sets.

Concerning the boots provided by the cruise company. They were Wellington-type boots with relatively thick soles. But you could feel the uneven surface through the boots. Some people brought boot liners, which I thought was a good idea. Also I picked a pair of boots that felt fine, but I realised later that I was lucky. The boots were just a little too tight, but I could still put them on. I should have picked a pair slight larger. Firstly, I could then have used two pairs of socks plus a liner (luckily I did not need this option). Secondly, they would have been easier to put on, and pull off. One additional comment touches on the waterproof over-trousers. You really must be able to tightly close them over the tops of the boots. Getting in and out of the zodiac will be in water, possibly ankle-high, possible nearer knee-high, and you don’t need water getting into the boots. There were a number of people who had poorly designed over-trousers.

I had brought a good pair of waterproof gloves, and two pairs of glove liners (camera and phone compliant). I found myself constantly putting on and pulling off the gloves to take photos. The waterproof gloves were just a size too small. They were big enough to take the glove liner, but it was always a flight to get them on and off when on the zodiac or walking in snow. I found that my finger tips would quickly get cold, and then a little later would warm up again. Returning home I immediately bought a pair of waterproof gloves two sizes bigger.

I had brought a wool hat and a balaclava. The hat was a touch too small, and I would have easily lost it during the trips on the zodiac. But I had the balaclava, which was by far the better option.

I had brought with me walking polls, snow goggles, binoculars and a day pack, but actually I never used them (I had two pairs of dark wrap-around sunglasses). They collectively represent well over 1 kg, and occupied quite a lot of space. However, many people did use theirs, so it’s worthwhile understanding what you will really need and use.

Washing instructions

Visiting the Antarctic means also understanding washing instructions. I ended up with a variety of clothes, a mix of new with some old friends.

The merino wool “base layer” clothes must be first turned inside out. If machine washed it should be cold and on a gentle cycle (like colours). They can be machine dried on low heat (but not recommended), or laid flat (which is recommended). No bleach. No fabric softener. No dry cleaning, Must not be wrung dry or hung to dry.

The merino wool socks must be machine washed cold, and hung to dry.

Washing instructions are great, but it was my understanding that anything given onboard for washing, suffered the same routine, namely machine washed at 40°C and spin dried.