My collection on Cádiz includes Cádiz I, Cádiz – II, Cádiz – Today, Cádiz – Maps, Models and the Camera Obscura, Cádiz – El Centro, Cádiz – El Pópolo, Cádiz – El Mentidero, Cádiz – San Carlos (this posting), Cádiz – Nochebuena and Nochevieja, and Cádiz – Trafalgar.

The barrio San Carlos is named after Carlos III de España (1716-1788). It all started with a fortress wall open to the Bahía de Cádiz. It was a continuous stretch of wall, built in the late 18th century, and originally including 55 vaults and a potential to house 90 cannons.

There are a number of sources mentioning the need to link two fortresses, San Antonio and San Felipe (they no longer exist). The first proposal by the military engineer Ignacio Sala appears to date from 1730, but the work did not progress because of the lack of funds. I think he moved on, because in 1749 he was already governor and Commander in Chief of the city of Cartagena de Indias. Anyway in the 1760’s the work continued, but there was also a pressing need for new land within the town. Given that the new fortress wall also worked as a breakwater, the enclosed land could be considered for development.

At least one source still mentions Ignacio Sala working to find new funding to complete the fortified wall. Several options were considered, including selling or renting the “new” land. It was finally suggested to allocate the land for new factories. The new barrio would be named San Carlos, and this was agreed in 1781, along with granting the auction of 120 bullfights to help with the costs.

In 1784 there was an additional proposal to allocate five enclosed plots for private houses, and in 1787 it was proposed also to rent out some of the 55 vaults in the walls. So finally the barrio became a fine example of the way to join defensive, urban and commercial interests.

In 1770-1775 Marshal Alejandro, Conde de O’Reilly (1722-1794) was in Cádiz to organise six new Spanish regiments, and some sources state that he was (or later became) the Governor (gobernador) of Cádiz. We know he returned to Cádiz, because he died there in 1794. Anyway it is said that once the walls were completed he requested that the new building projects have a specific aesthetic, e.g. Neoclassical façades. This meant avoiding anything overly Baroque, for example, watchtowers (torres-miradores), decorated and painted walls (decoraciones pintadas), and tiled walls (cerámicas), which were all much liked at the time. And we know that this requirement was included in local building requirements in 1797.

Just as an aside, the story of this Conde de O’Reilly is quite impressive. Born in Ireland he became the Inspector-General of Infantry for the Spanish Empire. He was Spanish governor of the colonial Louisiana, he reforming the defences of Havana in Cuba, and in addition became known as the farther of the Puerto Rican militia.

Anyway, the new land was added to existing land in Cádiz to make up a new barrio. At the time (1770) it was planned to build three substantial and identical buildings around an earlier Plaza de España within the San Antonio fortress, e.g. la Aduana, la Casa de Contratación and el Consulado. The Casa de Contratación would have been responsible for approving voyages to the Spanish colonies and thus indirectly also for collecting the colonial taxes and duties due. Finally only la Aduana (customs building) was completed in 1784, at a cost of more than 7.7 million reales. It is now the seat of the provincial government.

So San Carlos is a relatively new barrio in the city. There are administrative plans that define the exact extent of some barrios, but I have not found any plans for this barrio. It looks as if initially San Carlos consisted of only the five new building sites (cinco manzanes), and 6-7 streets (calles). But it appears to have been joined with another existing barrio called San Francisco making up an entirely residential barrio for aristocrats and rich traders. So no shops, just desktops (escitorios) as one old text put it.

Next to the wall there were also some apartments for employees, artisans and low-grade military. According to some old texts the original two barrios touched, today the “new” barrio San Carlos now touches the barrio El Mentidero along C/Zorrilla, and includes Plaza de Mina (and thus the Museo de Cádiz). I guess today it must also include the Iglesia San Francisco and Plaza San Francisco (and I presume also the Casa de los Lilas), as well as Plaza de España with the Casa de las Quarto Torres, the Casa de las Cinco Torres, and the Diputación Provincial.

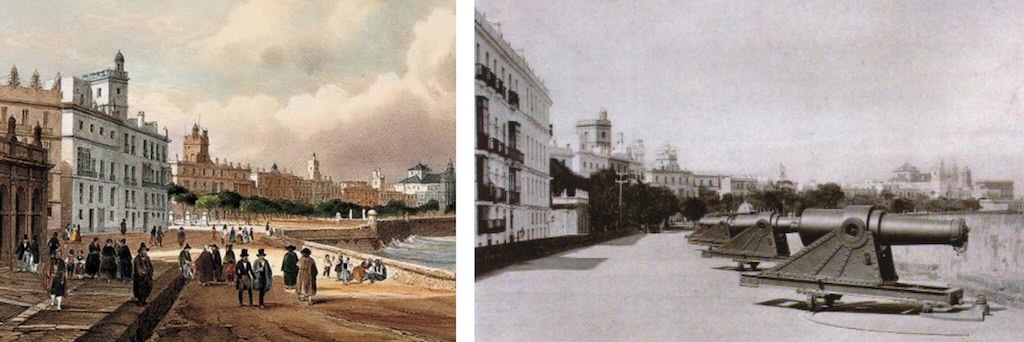

Below we have two different images of the same location along the defensive wall. You can see in the distance the Alameda Apodaca, and just make out Iglesia del Carmen in the far distance (both in the barrio El Mentidero). As we will learn below, a portion of the defensive wall was later removed to create a space for the Plaza de España, and of course later still the defensive wall was modified again with the building of the modern port.

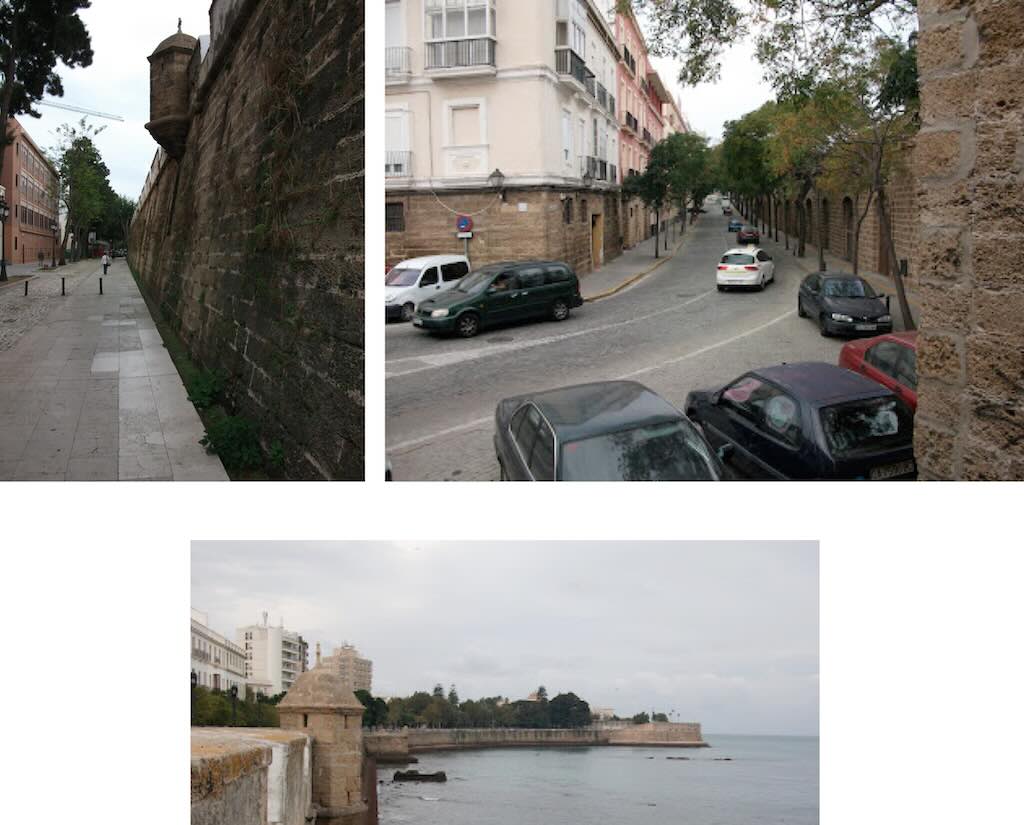

Below we have three photographs of barrio San Carlos today with the remaining defensive walls. You can also just make out some of the storage vaults built into the walls.

This brings us quite quickly to some of the buildings that existed before the fortress wall was completed. The first is the so-called Casa de las Cuatro Torres, which was built between 1736 and 1745. It is in fact four houses built in the Baroque style by a certain Juan Clat Fragela, a Greek trade, originally born in Damascus, but then established in Cádiz. Clearly the intent was to gain social prestige and display the enormous wealth of the owner, but the towers are considered by many to be the most successful and most monumental of all the towers built in Cádiz. We can see the detail of the smaller “sentry” towers that cover the stairs that provide access to the tower roofs. I understand that the owner finally rented out the houses to local traders who needed to watch out for their ships returning from the Americas. In 2014 these houses certainly needed a major restoration.

Below we can see the nearby Casa de las Cinco Torres, built around 1771, and in a transitional style between Baroque and Neoclassical. These are in fact five separate houses in Plaza de España, each with four floors, a small courtyard and a tower.

These type of houses were typical for traders working with the Spanish colonies in the Americas. The watchtowers were used to watch for the entry of their vessels so they could quickly get to the port and control the landing of their goods. The lower floors would be for offices and store rooms, the family rooms were on the second floor, and the servants slept on the top floor and manned the lookout tower.

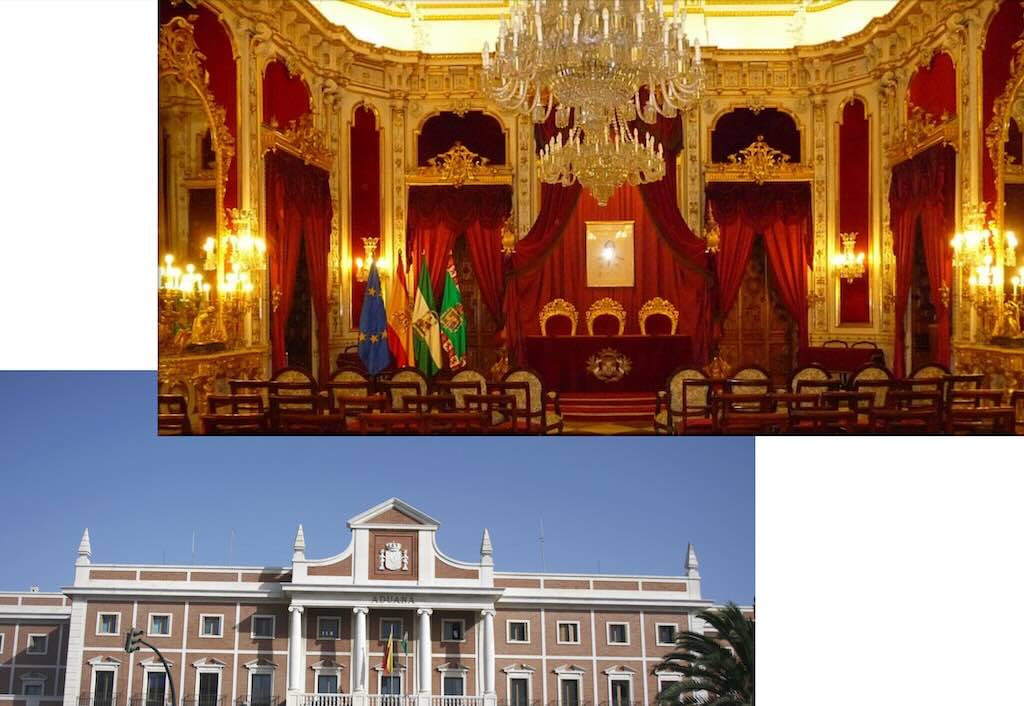

Nearby we have la Aduana, which in this case was a customs building, but more generally it’s a name given to a public government building having some form of fiscal role and situated near an international terminal on the coast or a frontier. Our Aduana was also built during the period 1770-1784, and in a Neoclassical style (a style that initially emerged around 1715-1730 and arrived in Spain in the 1760’s). We have to remember that the monopoly for trade with the Americas was transferred from Sevilla to Cádiz in 1717 so la Aduana was strategically placed in the fortress San Antonio which protected the maritime gateway to the city (this fortress no longer exists).

For the period it is quite simple and sober, with pillars of local “oyster stone”. My understanding is that the building has undergone quite a number of modification, with the front being renovated in the late 19th C. A few years ago there was a public outcry when it was decided to paint the exterior in pink (the original colour), but people have now become used to it.

The modifications did not affect the famous Salón Regio de la Diputación which is still in its original condition. It was designed by the architect Juan de la Vega for the visit of Isabel II in 1862. It is in the French Renaissance style, with a floor of black and white marble slabs, and lots of cedar wood, mirrors, and velvet.

The building finally became the seat of the provincial government in 1963.

Here we can see a reconstruction of the area. We have the Casa de las Cuatro Torres, the Casa de las Cinco Torres, la Aduana, and the original defensive wall. We can see where they will build Plaza de España (see below), and later still the new port.

Above we are looking at Plaza de España, with the la Aduana, the seat of the provincial government on the far left. We can also see the Casa de las Cinco Torres in the background, and we can even just make out the Casa de las Cuatro Torres in a backstreet on the right.

Sitting in the middle we have the monumental statue of las Cortes de Cádiz, celebrating an event that I had not come across in the past, namely the Constitución Española del 1812. We are in a period when Spain was occupied by the French, in what some call the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), and more specifically the Peninsular War (1807-1814), and what the Spanish call la Guerra de la Independencia Española (1808-1814). The Cortes were advisory councils made up of powerful feudal lords closest to the king, the earliest was the Cortes de León in 1188. Through the 12th C to 15th C some rich bourgeoisie were admitted, but the Catholic Monarchs (1474-1516) reduced the power of the Cortes. Through the 16th C and 17th C the Cortes retained some power over economic affairs, especially taxes. In 1808 Napoleon had taken control of most of Spain, and many of the representatives of las Cortes took refuge in the fortified coastal city of Cádiz. So local people were elected to represent the missing Spanish provinces, and liberal fractions pushed through the Constitución Española del 1812, the first Spanish constitution. Ferdinand VII upon returning to power in 1814 threw it out, but was forced to reintroduce it during the Trienio Liberal (or Three Liberal Years 1820-1823). Ferdinand VII actually invited the French back into Spain in order for them to restore his absolute power (oddly enough many of the Spanish liberals fled to France). We don’t intend these pages as a history lesson, but it is worth knowing that once Ferdinand VII was “liberated” he avenged himself with a vengeance, before become torpid and dying in 1833 (see the so-called Década Ominosa).

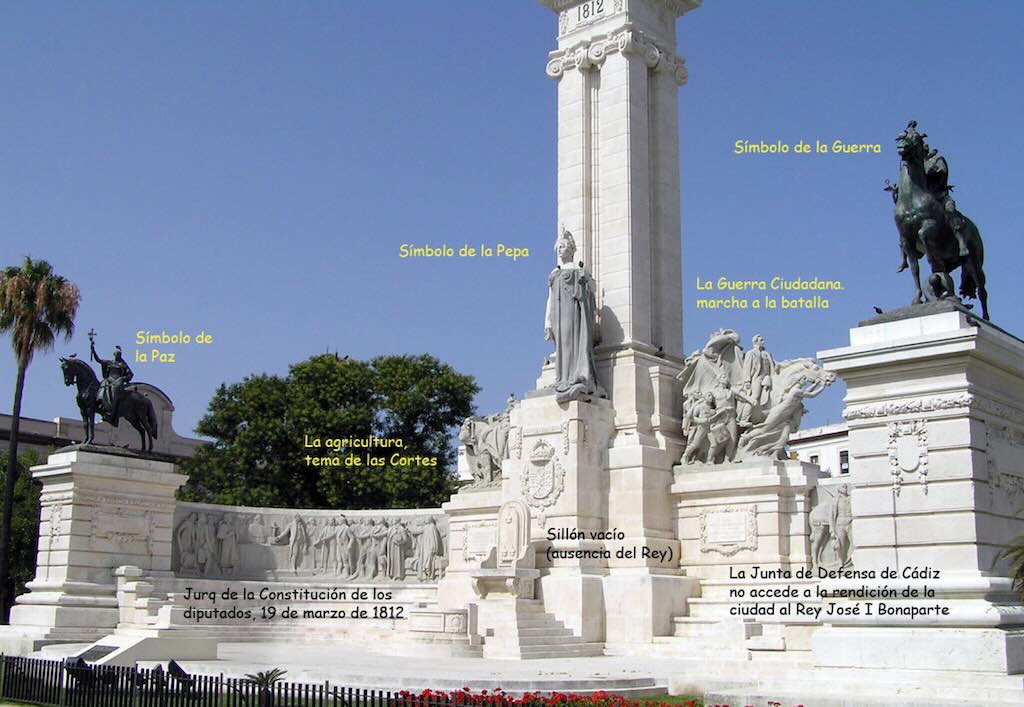

The most important recent change in the barrio was without doubt the demolition of part of the original fortress wall in the early 20th C. The current Plaza de España, includes the old Plazuela del Carbón. And as the name suggests this was the site of the coal store and fuel tanks in the old port, but now the plaza is seen as a part of the barrio San Carlos. At the time the goal of the demolition was to create a grand new Plaza de España to mark the 100th anniversary of the Constitución Española del 1812, and provide a setting for a memorial. The design was by the architect Modesto Lopez Otero, and the sculptor was Aniceto Marinas. The work began in 1912 and finished in 1929.

The lower level of the monument represents a chamber and an empty presidential armchair. The upper level has various inscriptions surmounting the chamber. On each side are bronze figures representing peace and war. In the centre, a pilaster rises to symbolize, in allegorical terms, the principals expressed in the 1812 constitution. At the foot of this pilaster, there is a female figure representing Spain, and, to either side, sculptural groupings representing agriculture and citizenship. The below photograph is one of a great series of annotated photos of the Monumento Constitución 1812 in Plaza de España.

Just behind the Museo de Cádiz and the Plaza de Mina there is the far smaller Plaza San Francisco, home to the Franciscan Convento de San Francisco. Founded in 1566, rebuilt in the 17th century, and modified in the 18th century, it is today a small Baroque church, with a certain Italian influence (e.g. the use of Tuscan columns). It has been said that its bell tower was used during the siege of Cádiz, and the bells were rung to warn gaditanos of the French attacks. My impression is that this church must have been the centre of the old barrio San Francisco before it was included within the newer barrio San Carlos.

This plaza is actually divided into one small rectangular square in front of the church, and an even smaller plaza to the side of the church. I guess in the summer this could be a nice square in which to sit down, drink a beer, and have some tapas.

I remember the church being very small and poorly lit, but even in poor light the Rococo altar was impressive. I’ve seen photos of what looks like a nice cloister with marble columns.

In most cities Franciscan and Dominican convents were placed outside the city walls, but next to the gates. This was ordered so that they could fight the Protestant Reformation by checking the faith of all those entering through the gates. But in Cádiz the “wall” was the sea, so the convents were located near the port.

Museo de Cádiz

We have almost finished our visit to the barrio San Carlos. We only have left the Museo de Cádiz in Plaza de Mina.

In fact Plaza de Mina was originally the orchard of the Convento de San Francisco. It is said to have remained relatively unchanged since the 1840’s. It was also where the musician Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) was born.

The plaza is also home to several political associations, and this probably explains why we found it quite crowded on a number of occasions. It was full of people drinking beer, and just chatting.

The Museo de Cádiz (and in English) is small, but surprisingly interesting. The ground floor is devoted to the archaeology of the city (most Phoenician and Roman), and the first and second floors to a collection of paintings (someone said there were puppets on the second floor but we did not see any).

We are going to visit just a few of the more interesting items. And the most interesting (and important) are two sarcophagi in cut and polished white marble. There are more than 2 m long, and date from around 400-470 BC (Punic period or peoples from Carthage).

I was particularly impressed with the jewellery, and the fineness of the workmanship.

The collection of paintings is focussed less on quality than on provenance. It represents artists from the region, and what rich locals would have admired and collected. The focal point must be a series of paintings by Zurbarán (1598-1664) confiscated in 1835 from la Cartuja de Jerez de la Frontera. The centrepiece (above) represents Apoteosis de San Bruno.

Above we have an auto-portrait of Victoria Martín de Campo (1794-1869) who was born in Cádiz. Also known as Victoria Martín Barhié, she was a notable Spanish neoclassical painter, and one of the few women of her time to gain institutional recognition in the Spanish art world. She was one of the first women admitted as an honorary member to the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid, a highly prestigious art institution in Spain.

Born and raised in Cádiz, Martín de Campo’s life and work were deeply intertwined with the city’s cultural fabric. She produced works with religious themes that are currently housed in Cádiz Cathedral. In 1847, Martín de Campo became the first woman to be named an “Academician of Merit” by the Academy of Fine Arts of Cádiz, a significant achievement given the gender constraints of the era.