This post starts with USB-style cables, then looks at power cables, AC adapters, etc. This post can be read along with Tech – Apple cables and accessories.

Over the years my wife and I had given a warm and safe home to all those forlorn cables that were found abandoned around our homes. Every domestic device and appliance appears to need at least one cable, possible two, and better still, three. My power cables, telephone cables, computer cables, chargers, etc., when no longer needed, somehow ended up in boxes stacked on the top shelf in our overcrowded storeroom. Some were elevated in status to “spares”, whilst others were relegated to the more lowly “just in case”, or even down to the generic “who knows, might come in handy one day” (and we all know what that means).

Some years ago I did take a pile of old telephone plug cables (mostly RJ11’s) down to the local recycle centre, but all the other cables continued to live happily in three quite sizeable plastic boxes. I had my suspicions about putting a lot of “male” and “female” connectors together in the same box, but I preferred, as they say, to “let sleeping cables lie”.

I will admit to having an almost unhealthy liking for cables, wires and connectors. I spent my early years as an experimental physicist, and in a laboratory I would never throw away a nice piece of unused wire, or any type of cable or connector. In fact I would prefer to never throw anything away that could be “valuable stock”. Just as mechanics hang their tools, so I would have racks to hang a zoo of cables with their plugs and connectors. And there were boxes to collect bits of wire, spare bolts and screw, and any useful bits of metal, plastic and wood. The key point was that if I could not find a use for it, a friend in the next lab might need just that piece of stuff. And I won’t mention how we treasured all sorts of unusual tools and various old measurement instruments, etc.

Back at home, in late 2024 I finally got a fibre pulled from the street up to my home network, and lo-and-behold, another couple of cables were left on the floor by the installation technician.

It was time to decide what I really needed to keep, and condemn the rest to the long walk to our local recycle centre.

The first step was to find out what cables I was using, and then look at what spare cables I might still need.

Finally there was the problem of duplicate cables. I might still want to keep one particular cable, but did I need to keep two-three-five of them?

Computer cables today

In many ways the computer is at the heart of today’s “spider’s web” of home cables. As an example, let’s start with my workspace. It’s home to my latest laptop, a Space Black MacBook Pro, which has:-

- SDXC card slot

- HDMI port for digital video output (one external display at 4K resolution at 240Hz) and multichannel audio output

- 3.5 mm headphone jack with support for high-impedance headphones (specifically a triple ring headphone socket which supports headphones with microphone, but there are numerous standards that use this model jack)

- MagSafe 3 port (connecting to a 70W USB-C power adapter with a USB-C to MagSafe 3 cable)

- Three Thunderbolt/USB4 ports, supporting charging, DisplayPort, Thunderbolt 3 (up to 40Gb/s), and USB4 (up to 40Gb/s).

Let's start with USB

My first “spare” cable was a wonderfully “well documented” one with two different types of connections both with the USB trident logo. What we see here is a USB cable with two different “male” connectors. This cable has the four wires (+5V, data-, data+, and ground), and the two different connector shapes ensured that the cable could only be installed in one direction. This was because only “downstream” ports provided power, with the flat “A” connection inserted it carried both power and data. Some people might remember keyboards or mice with captive (pre-installed) cables with only the flat “A” connectors to be inserted into a downstream port on the computer. I remember the squarish “B” connector was often used for the “upstream” ports on printers.

Just for completeness, the terms “male” and “female” should only be used for individual pins and socket contacts, but in general usage they are also applied to the complete plugs and connectors.

The cable itself had printed along its length …

AWM 2725 80°C 30 V VW-1

LL64201 CSA AWM I/II A 80°C 30V FT1 COPARTNER

USB/FS <28AWG/1P+24AWG/2C>

E188601-U (UL) CM 75°C —–

… and repeated down its entire length.

How could I send such an important looking cable to the recycle centre?

Firstly we have AWM (Appliance Wiring Materials), style 2725, which is a multiple-conductor cable in a non-integral jacket. And the temperature and voltage were maximum limits for flame transmission down the length of the cable. The cable type is for two to four twisted insulated singles, or groups of twisted singles twisted together, or groups of twisted singles, all laid parallel, forming a flat or oval cable. The cladding is extruded PVC, 9 mils minimum average thickness, 7 mils minimum thickness at any point. This type of cable was for internal wiring of electronic equipment in Class 2 systems only. Class II (or 2) is for double insulated electrical appliances with reinforced protective insulation in addition to basic insulation. So this means equipment that has been designed in such a way that it does not require a safety connection to electrical earth (ground).

CSA means the Canadian Standards Association, and LL64201 is a specific manufacturer code, in this case for a Straight Universal Extension Cable (not the connectors). The other codes refer to maximum temperature certification and burning characteristics, and COPARTNER is a US brand.

USB/FS is a full speed USB standard introduced for USB 1.0. Some of the codes describe the number of conductors (e.g. 2C), pairs (e.g. 1P), and 28AWG and 24AWG is the American Wire Gauge.

E188601-U is also the part number from a specific manufacturer. CM is the material class for the cable, and the temperature indications, such as 75°C, does not mean that the cable will combust at this temperature, but rather that the plastics used will slowly degrade if kept above this temperature for extended periods.

Here is a useful description on how to read cable jackets.

So given the type of cable, plus its colour, my guess is that it was the cable for an old HP printer.

So yes, I did send this important looking cable to the recycle centre. And in fact I sent five of these cables for recycling.

USB stands for Universal Serial Bus, and is an industry standard that allows data exchange and delivery of power between many types of electronics. It specifies an architecture, both the physical interface and the communication protocols for data transfer and power delivery to and from hosts (the name given to all types of personal computers and peripherals). Serial just means sending data one bit at a time, sequentially, over a communication channel or computer bus. And a bus is the name given to a communication system that transfers data between components inside a computer, or between computers (and includes both hardware components (wire, optical fiber, etc.) and software, including communication protocols).

The cable seen above conformed to 1998 USB 1.1 (which had rapidly replaced the original 1997 USB 1.0). USB 2.0 released in 2000, was backward compatible with USB 1.1 and used the same connectors.

Also in 2000 the mini-USB was released for smaller devices such as digital cameras, smartphones, and tablet computers. However, by 2007 these were replaced by the micro-USB for use with smartphones, personal digital assistants, and cameras.

In 2008 the USB 3.0 specification was issued and marketed as SuperSpeed USB. This was upgraded to USB 3.1 in 2013, and again to USB 3.2 in 2017, and became SuperSpeedPlus USB. There was also a new micro-USB 3.0 specification. The most noticeable difference was that the USB 3.0 Type-B plugs were larger than USB 2.0 (or earlier) Type-B plugs, and could not be inserted into USB 2.0 (or earlier) Type-B “receptacles” (the official name for the female connector slots). The upgrades essentially targeted higher transfer rates, and the USB 3.0 Type-A and Type-B connectors are usually blue, to distinguish them from the USB 2.0 connectors.

In 2014 the USB-C specification was issued for audio, video, and other data, and to connect to monitors or external drives, including the ability to provide and receive power from devices such as laptops and mobile phones. It used not only USB technology, but was also compatible with other protocols such as Thunderbolt, PCIe, HDMI, DisplayPort, and others.

The easiest way to understand the differences between USB-C vs USB 3 is that one describes the connector (USB-C), and the other is the data transfer technology (USB 3). In fact USB-C is electrically compatible with older USB 3.0 ports, but the shape of the connectors and port are different (adapters do exist).

In 2017 the USB 3.2 specification was issued, doubling the bandwidth for existing USB-C cables, up to 20 Gbit/s.

In 2019 USB4 was issued enables multiple devices to dynamically share a single high-speed data link, with a signalling rate of up to 40 Gbit/s. USB4 ports are on MacBook Pro’s starting with the M1 (Apple Silicon) in 2020.

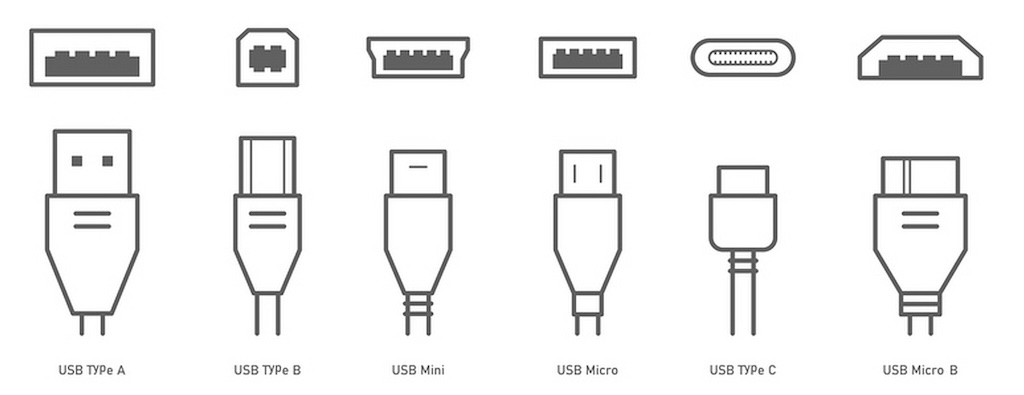

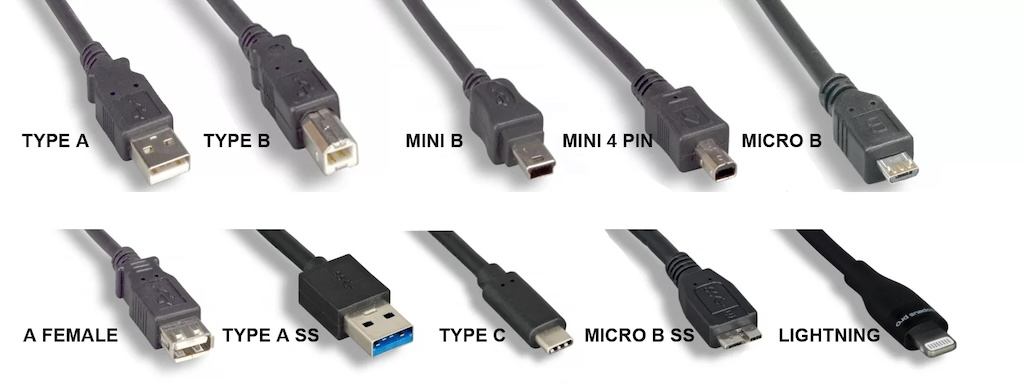

As we moved from USB 1.0 through to USB 3.0 and beyond, it became a little confusing to identify which cable was which. It’s for this reason that I have added the two above graphics. A number of the cables look very similar, until you look at the profile of the connector.

A major part of the problem was just to find out which of these cables are still used in my zoo of devices, etc. The below photo is on Wikipedia and shows the variety of USB cables on one market stall in Hong Kong.

I kept one non-standard USB extension cables, with a plug (male) on one end and a receptacle (female) on the other. USB does not support extension cables, so there is no guarantee that they work properly.

I kept three examples with the mini-B connector. Two were for mini-B to USB, but of entirely different lengths. And one was an unusual USB split to a short USB and a long cable to a mini-B.

I kept two micro-B to USB “just in case”.

I kept one cable with a USB 3 micro-B SS to USB 3 (blue connector), “just in case”.

I also kept one Thunderbolt 4 to USB-C cable.

All the other cables and duplicates went to the recycle centre.

Wikipedia tells us that the High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI) is a proprietary audio/video interface for transmitting uncompressed video data and compressed or uncompressed digital audio data from an HDMI-compliant source device, such as a display controller, to a compatible computer monitor, video projector, digital television, or digital audio device.

Given that more than 10 billion HDMI devices have been sold, this is sufficient reason to always keep all HDMI cables.

Its worth noting that there are several different HDMI cable certifications, ranging from “Standard” through to “Ultra High Speed”.

Below we can see the HDMI connector on the left, and the DisplayPort on the right.

Wikipedia tells us that the DisplayPort (DP) is a proprietary digital display interface, and the cable is primarily used to connect a video source to a display device such as a computer monitor. It can also carry audio, USB, and other forms of data.

DisplayPort and HDMI have similar specifications, and I can’t see much reason for preferring DisplayPort over HDMI. In most cases it’s a non-question, e.g. my MacBook Pro has a HDMI port for connecting to my computer monitor.

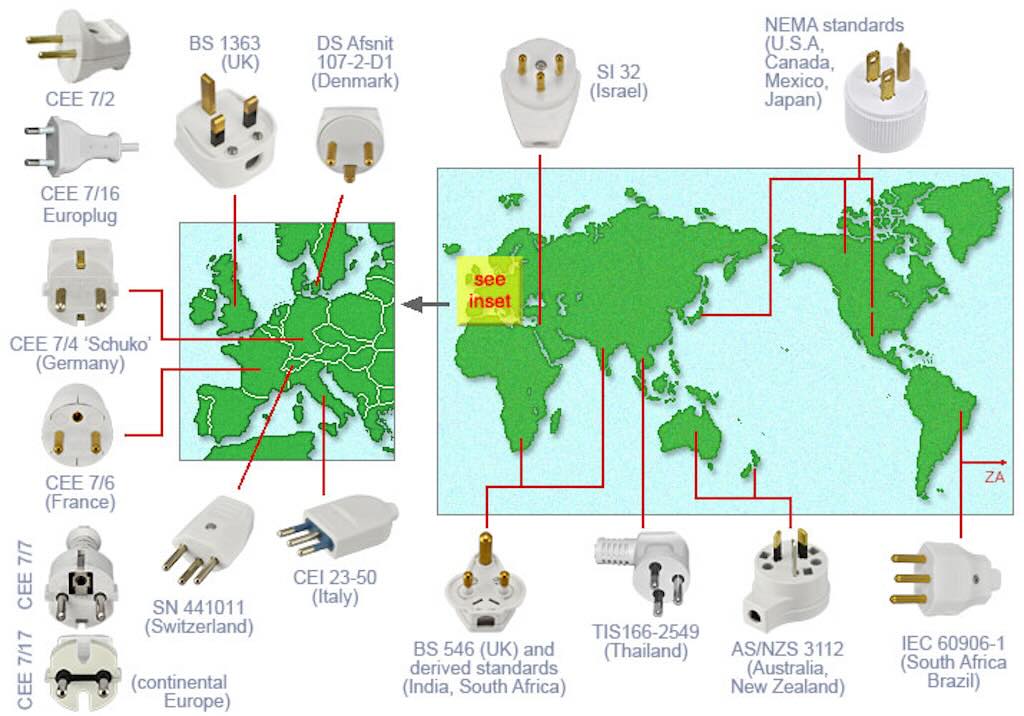

Power cables

Whilst absolutely vital in today’s world, it’s not just about computer cables. There are charger/power cables (or power/mains cords) which are often ignored, but are just as important.

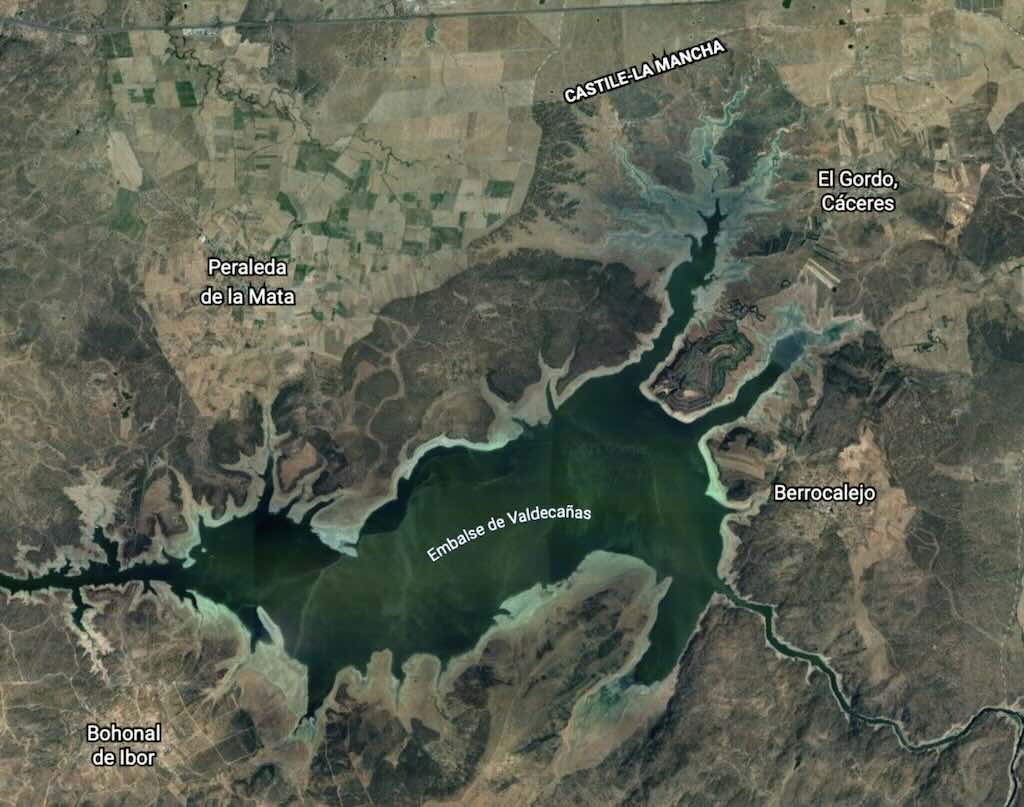

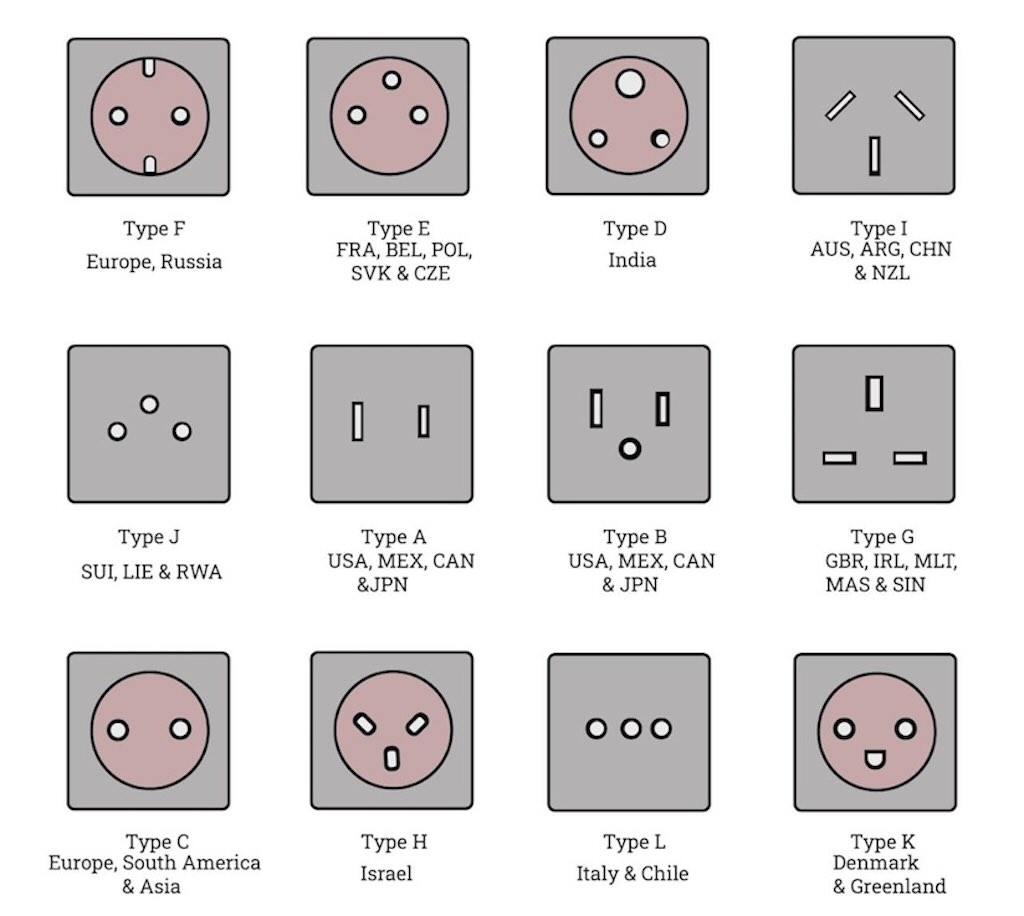

The above world map comes from the Museum of Plugs and Sockets.

I have a variety of power cables fitted with the CEE 7/7 AC plug with two round pins and earthing clips on both sides, ready to take an earth pin of the CEE 7/5 socket. The above photos are of a Type E (on the left with the earth pin in the socket) and a Type F (on the right without the earth pin but with the earth clips on the sides). The Type E derives from a French standard, and the Type F is the same as the German “Schuko“, but what’s important is that the CEE 7/7 plug is compatible with both.

This set of cables are fitted with the IEC 60320 C13 connector (sometimes incorrectly called a “kettle cord“) which is used in a wide variety of electronic equipment ranging from computer components like the power supply, monitors, printers and other peripherals through to instrument amplifiers, professional audio equipment and virtually all professional video equipment. The C13 connectors are only rated for 70°C, and a kettle (thus a “kettle cord”) would actually need the C15 connector, which is rated for 120°C. The C15 connector has a notch, and, for example, a kettle requires the C15 connector with the notch, and normally would not accept a C13 connector without the notch.

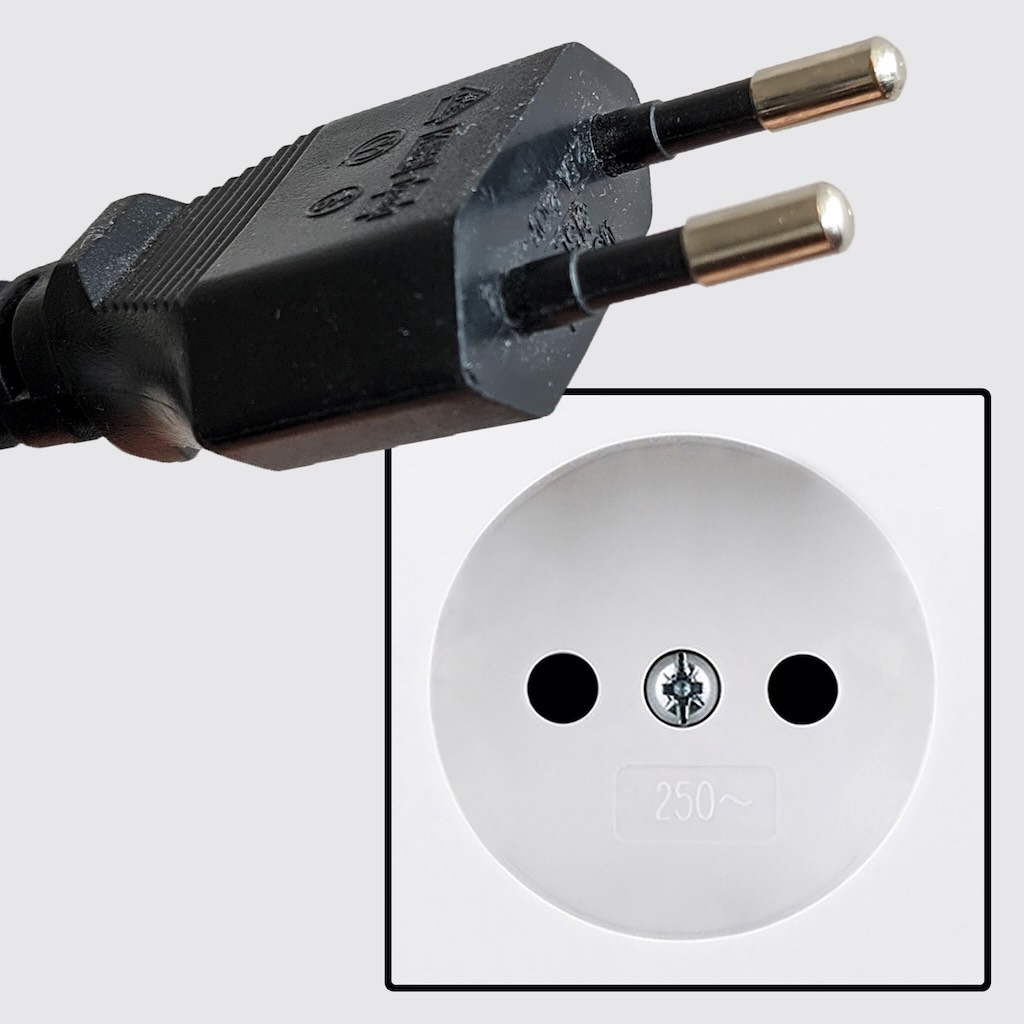

I also have a variety of power cables fitted with the so-called Europlug, used for low-power Class II appliances. This can be used with many different forms of round-pin domestic power socket used across Europe. These cable are fitted with International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 60320 “appliance couplers” normally used for connecting power supply cords to electrical appliances not exceeding 2.5 A 250 V.

In fact this connector is identified as C7/16 and is a two-wire ungrounded and unpolarised plug with two round prongs. There is also a second, less frequently used version of the type C plug (the C7/17), which is also unearthed but is rated at either 10 A or 16 A. It looks completely different, but its pins have the same length (19 mm) as the 2.5 A version, however they are not insulated and have a slightly larger diameter (4.8 mm instead of 4 mm). The shape of the C7/17 is compatible with CEE 7/1, CEE 7/3, and CEE 7/5 sockets.

My Europlug cables (all C7/16) are fitted with the IEC 60320 C7 connector, the so-called “figure 8 connector”. I also have one example of a UK plug also with a figure 8 connector.

It’s important to note that in principle Europlugs must be non-rewirable and must be supplied pre-attached to a power cord. Anything else is non-compliant, and could even invalidate an insurance policy if they were the cause of a fire.

Both the C7 and C13 connectors are part of the Type C family of connectors and are the most widely used plugs internationally.

You can also find Europlug-style extension leads, such as a IEC 60320 C7 to C8 (so with male and female connections). However all my extension cables are simple male to female Europlug extensions, and some are the coiled variety.

For completeness, “connectors” and “appliance outlets” are fitted with socket contacts, and “appliance inlets” and “plug connectors” are fitted with pin contacts.

The most important thing I did was to take to the recycle centre all cables that had been rewired with different plugs. My aim is to use only non-rewired cables with thermally sealed plugs and connectors.

AC adapters are everywhere. These are little external power supply units, usually integrated into something looking like an AC plug.

What they do is provide electric power to devices that lack internal components to draw voltage and power from mains power themselves.

Many modern-day adapters charge the battery on battery-powered devices such as smartphones. And we all soon learn the importance of the “charger”, when sitting in a hotel room and discovering that we left it at home.

The first type of AC adapter has a coaxial power connector. The first thing people look at is what looks like a “male” barrel plug usually attached to a thinnish two-strand insulated cable. This is not the way to define a coaxial power connector.

Firstly coaxial power connectors are cylindrical DC connectors, that are defined by their internal diameter, not the external diameter. And secondly, because the key characteristic is the internal size of the cylinder, they are “female” connectors. The rarer male coaxial power connector does exist and has a pin sitting in the centre of the cylinder.

Another feature often not noticed (in part because it is quite rare) is a ring-shaped “locking detent” or “high-retention feature” intended to prevent accidental disconnection. Typically, this is a conical cut-back section of the tip, just behind the insulator that separates the inner from outer contact surfaces.

In examining the coaxial power connector I did find two where the insulator looked damaged or imperfect, and they both got their marching orders to my local recycle centre.

All but one of my AC adapters have connectors with an outer diameter of 5.5 mm, and an inner diameter of 3.5 mm. The length of the connector can vary around an average of about 9.5 mm, and mine vary between 9.5 and 12 mm in length.

The reality is that there are potentially hundreds of different types of AC adapters with coaxial power connector of different diameters and lengths, and its difficult to know which “spare” might be useful and which might be totally useless.

Here are my AC adapters with (3.5 mm) coaxial power connectors;-

- 230V AC 20mA to 9.3V AC 210 mA (3x Falcom AC to AC)

- 230V AC to 3V DC 250 mA (with warning to be used only in dry interiors)

- 230V AC 140mA to 12V AC 1A (AC to AC and dry interiors only)

- 100-240V AC 0.6A to 12V DC 2A 24W (Paulmann LED driver)

- 230V AC 21 mA to 3.7V DC 355mA (Nokia)

- 100-240V AC 125mA to 5.7V DC 800mA (Nokia)

- 100-240V AC 0.8A to 17V DC 2.3A

- 100-240V AC 0.5A to 12V DC 1A

- 220-240V AC 500mA to 12V DC 2A (office equipment only)

- 230V AC 65mA to 6.5V DC 600mA

- 100-240V AC 0.6A to 25V DC 0.5A (Electrolux).

Popular today are the AC adapters with a USB connector, and no USB cable. These are dedicated USB power adapters that can run attached devices and charge battery packs. In technical terms this type of charger places a resistance not exceeding 200 Ω across the D+ and D− terminals, and this means that the charging device is identified by non-data signalling on the D+ and D− terminals. Originally these type of AC adapters provided 5V DC and 500-900mA, but standards are constantly evolving.

Each of my AC adapters would need a USB connector cable, and were rated differently. All, as expected, had an input of 100-240V 50-60Hz, but with differing current ratings, between 0.2A to 0.6A. And all the adapters had different DC output ratings, all 5V DC but with a current rating of anything between 500mA up to 2.1A (2.5A max).

One AC adapter auto-switched between 5V 3A 15W, through 9V 2A 18W, to 12V 1.5A 18W.

All these AC adapters appear to conform to the latest USB power delivery rules for any type of USB cable between 5V and equal/below 3A and 15W, up to 20V and equal/below 3A and 60W.

Over time the USB power adapters have evolved to faster and faster charging options. From 2021 the Extended Power Range (EPR) mode allows higher voltages of 28V, 36V, and 48V, providing up to 240W of power (48V at 5A), and the “Adjustable Voltage Supply” (AVS) protocol allows specifying the voltage from a range of 15V to 48V in 100mV steps.

So I kept four different (non Apple) USB AC adapters of different ratings, “just in case”.

I also kept an AC adapter with a fixed micro-USB connector. It’s rated for 100-240V AC 0.5A to 5V DC 2A.

Having no basis for deciding what to keep and what to throw, I tend to keep all AC adapters that have a potential to be spares and reused. All spare AC adapters go in a small draw, and what I keep or throw simply depends on the size of that small draw, i.e. when its full, I sort and throw.

A final points was that I even had a switchable charger (1.5V to 12V 800mA), with 13 different connectors, that used the 12V cigar lighter socket in a car.

This final section is about travel adapters, those little devices that convert one electrical socket to another socket design. Some modify power or signal attributes, but most just adapt the physical form of one connector to another.

In it’s simplest form it allows one type of plug (e.g. British) to be connected to another type of socket (e.g. American or Australian).

Over the years I appear to have acquired quite a number of these adapters. I guess it all started in 1968 when I wanted to use British plugs in German sockets.

I kept the 5-in-1 Colour-Coded Universal Travel Adapter with 2 USB Ports, from Flight 001. This is small cube that breaks up into four different adapters (US, Australia, UK, Europe) and two USB ports.

This is not a voltage converter, but it does package well, and claims to cover 150 countries.

I can’t see any special reason to keep any of the below adapters, so all were taken to the recycle centre.

The oldest looked to be three examples of the Kopp “Travel-Star” Adaptor (you see both spelling for adapter and adaptor). This takes in the centre Euro and contour plugs, two-pin with no earth (i.e. so not for safety plugs), and adapts to sockets in Asia, Australia, North America, South America, Africa and Europe. You “dial” the central socket to the desired plug, e.g. Euro to US two-flat-pin.

I have a fused UK adapter (BS 5733) for European plugs (logo ![]() ), but only those not have a side-contact earth.

), but only those not have a side-contact earth.

BS 5733 is just a specification for general requirements for electrical accessories, and does not actually specify switched and unswitched socket-outlets, nor for rewirable and non-rewirable 13A fused plugs.

The presence of the logo ![]() on commercial products indicates that the manufacturer or importer affirms the goods’ conformity with European health, safety, and environmental protection standards. It is not a quality indicator or a certification mark.

on commercial products indicates that the manufacturer or importer affirms the goods’ conformity with European health, safety, and environmental protection standards. It is not a quality indicator or a certification mark.

I have a series of three adapters (Euro, UK and US) from Wonpro, that don’t quite nest together, and don’t appear any more on their website. My adapters are all with the same “Universal Adapter with Safety Shutter” front panel, and a two-pin Euro plug, or UK 3-pin plug, or US two-pin plug. My guess is that these are now models ST-6, ST-7 and ST-9C.

I also have an adapter from Pudney (P4320) which is for UK, US and Japanese plugs to New Zealand sockets.

I have an adapter from Boots for two-pin to Southern Europe and America/Australia (the pins can be coated using a small screwdriver).

I kept the 5-in-1 adapter, and sent the rest to the recycle centre.

Ready for the recycle centre (20 kg)