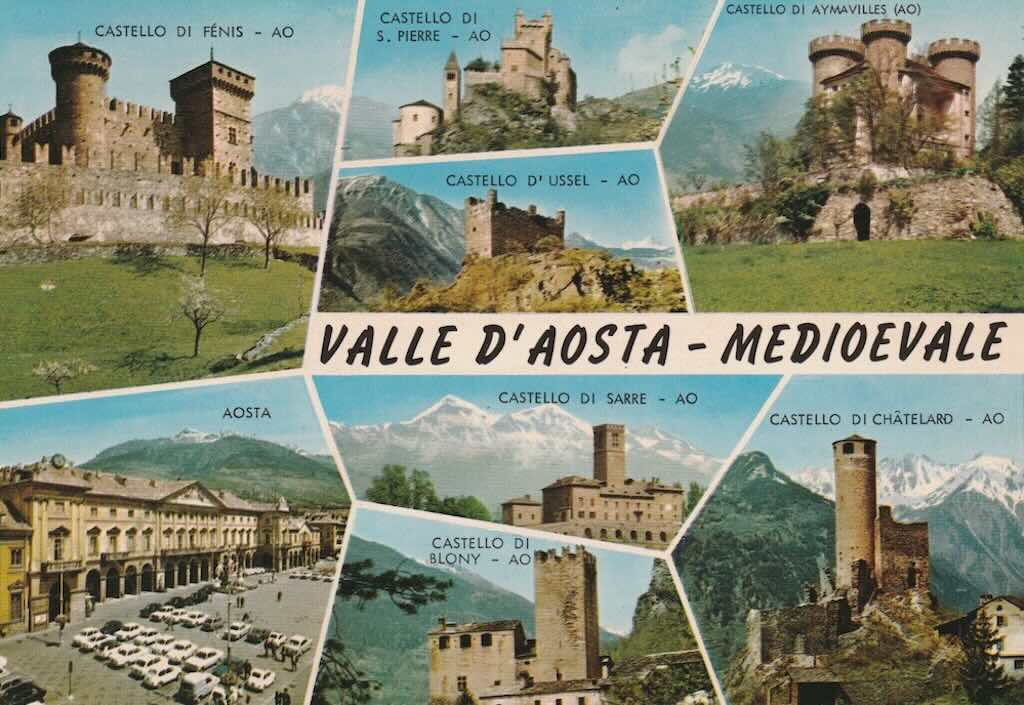

Over the years my wife and I had visited a number of the castles in Val d’Aosta. But even the best memories fade, so it was now time (September 2024) to visit some of them again.

This time with a friend, we visited the Royal Castle of Sarre, the Castle of Issogne, the Fort of Bard, and the Castle of Saint-Pierre.

Just to set the scene, below we have an introduction to the Val d’Aosta as seen by the 19th century traveller.

In fact the villages, chapels and castles in the valley were almost never visited because the appalling road conditions meant that most could only be glimpsed from the roadside. Travellers were left to comment on both the poverty and poor health of inhabitants and the decaying buildings. Some often noted in the Val d’Aosta the large number of cases of cretinism, which, according to William King, “in the many loathsome forms it assumes, of besotted vacancy, dwarfed elfishness, hideous disproportion, and generally conscious degradation, affecting every fourth person one meets, is the most melancholy spectacle of the defacement of God’s own image which the world can present“. Aosta was seen as “the head quarter of these frightful maladies, which more or less affect half of the population from Villenueve to Châtillon“. King queried the reason for the high occurrence of cases, commenting that people from the valley attribute it “to the filthy habits of the lower classes, who live in miserable dark hovels, along with animals, never changing their clothes or dreaming of washing“. He noticed, however, that “the people of Aosta are not more filthy than many other Italians or even the Irish“.

Visiting the castles in the valley, we will see a totally different image of the “better classes” that lived in the valley.

Val d'Aosta and its castles were an integral part of our life together

When Monique and I were living in Italy in the mid-late 70s and early 80s, we would drive to our apartment in the upper valley every Friday evening, and back down on Sunday night. We did this no matter what the weather conditions. The motorway had not been built through the valley, so we would drive down to Novara, use the Milan-Turin motorway, cut up to Ivrea, and drive up through the valley. In good conditions it would take a little over 3 hours to make the 220 km trip in Monique’s little green Autobianchi. If/when we hit snow, we had a set of special snow grips.

We could not go very fast, but we could go anywhere, even in deep snow. No matter how long it took us we would get to our apartment. The key was to avoid the lorries that would stop in the tunnels to put their chains on, so we knew all the small roads, and short-cuts. If the snowploughs had not yet arrived, I would dig us into our covered garage area. We could put our small car in our separate “box” (garage) but couldn’t get out of the car. So it was all about aligning the car up with the open garage door, and pushing it in, and pulling it out the next day. The rest of the evening was about lighting a fire, eating stuff we had brought with us, and snuggling up for the night (I still have our electric blanket).

Despite the Aosta autonomous region starting at Pont-Saint-Martin, in our minds it was the Fort de Bard that symbolised entering and leaving the valley. I remember trying to visit the fort in the early 1980s, but I don’t think it was open to the public. In fact, in the 70s and early 80s, most the castles were not open to the public, and many just looked semi-abandoned.

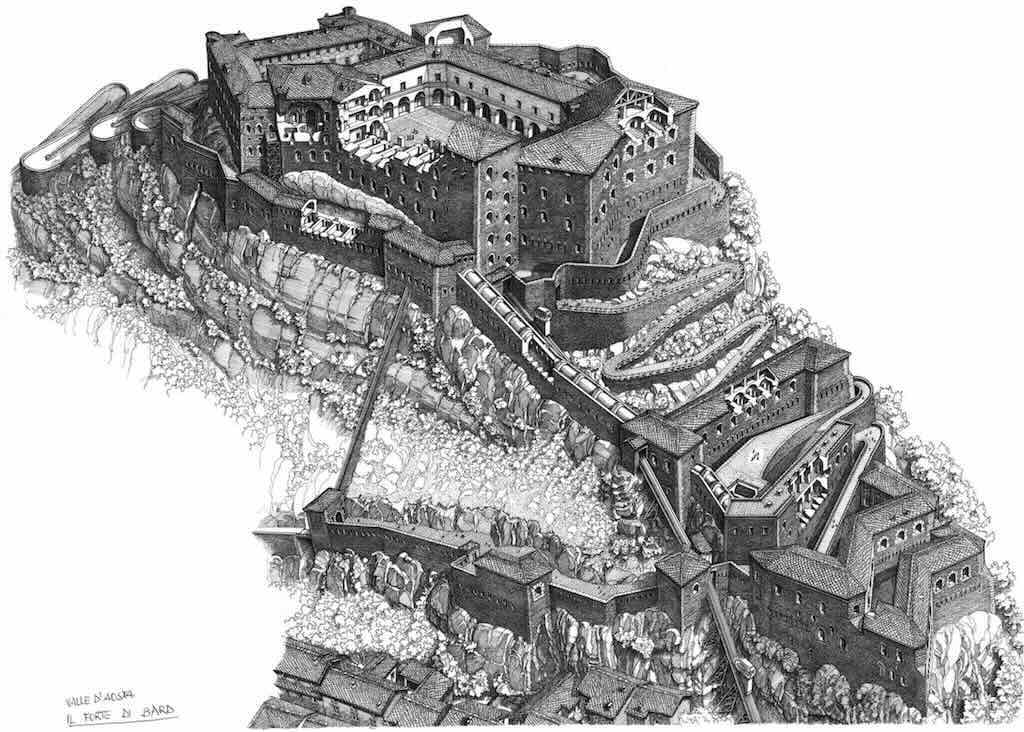

Above we have the fort of Bard as seen today driving down the valley. We can just see the multi-storey carpark down on the road, and there is a lift system to bring people to the top (you can also walk to the top). Today the motorway goes through a tunnel in the mountain on the right.

The first signs of human settlement in the gorge where Bard is situated was in the Eneolithic period (Bronze Age). The narrow passageway between the Dora Baltea and the sheer rock cliffs has always been an obligatory route into Valle d’Aosta. Dating back to the Roman period, the Gallic Consular Road, a greater part of which was cut into the rock, connected Eporedia (Ivrea) to the mountain passes of Alpis Graia (the Little Saint Bernard Pass) and the Alpis Poenina (the Great Saint Bernard Pass). The fort was built in 25 BC after the Romans finally defeated the Salassi, and it was used until the 19th century.

Given its highly strategic position in the control of the passageway into the valley, the imposing rock spur has been fortified since pre-Roman times. However documentary evidence does not go back that far. Some historians have identified the Ostrogoth King Theodore (493-526) as the first to install an armed garrison (clusurae Augustanae) in the 6th century.

The first written reference to a defence settlement dates back to 1034 and belonged to Viscount Aosta Boso (I guess a descendant of Boso of Provence) and his descendants dominated Bard until the first half of the 13th century.

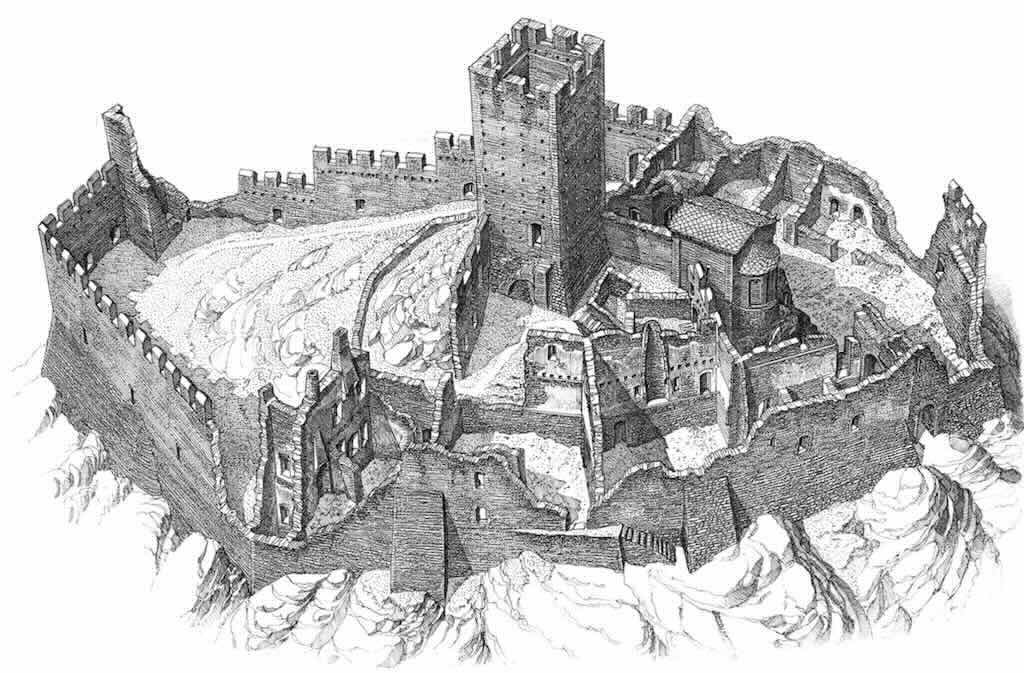

The castle then came under Savoy rule after being conquered by Amedeo IV in 1242. The castle consisted of a group of buildings dominated by a donjon (square keep) and enclosed by a double boundary wall armed with guard towers, and a system of bastions descended down the rocky spur to protect the village of Bard.

In 1661 the duke Carlo Emanuele II dismantled the Verrés and Montjovet strongholds and transferred the whole artillery to Bard which became the principal defence base of the armed forces of the Savoy dukedom.

During the Spanish Wars of Succession the resistance by Vittorio Amedeo II’s army against the French troops was a memorable one for Bard. But the most famous military episode witnessed by the fortress was the seige of 1800. At dawn, on the 14th of May, Napoleon’s 40.000 strong Armée de réserve crossed the Alps through the Great Saint Bernard Pass taking the Austro-Piedmontese army occupying the Po Valley by surprise. The invading troops soon reached Bard but were halted by the Austrian garrison defending the fortress.

During a night attack on the 21st of May the village of Bard surrendered to the French forces but the commander of the fortress, Captain Stockard von Bernkopf, did not give up the battle. The French General Marmont failed in his nightly plans to transport cannons up to the top of the fortified rock and after several unsuccessful attempts had no choice but to put the fortress under siege. Finally, on the first of June, after a whole day of bombardment, Captain von Bernkopf honorably accepted defeat.

Exasperated by the unexpected resistance, Napoleon razed the “vilain castel de Bard” (the villainous castle of Bard) to the ground.

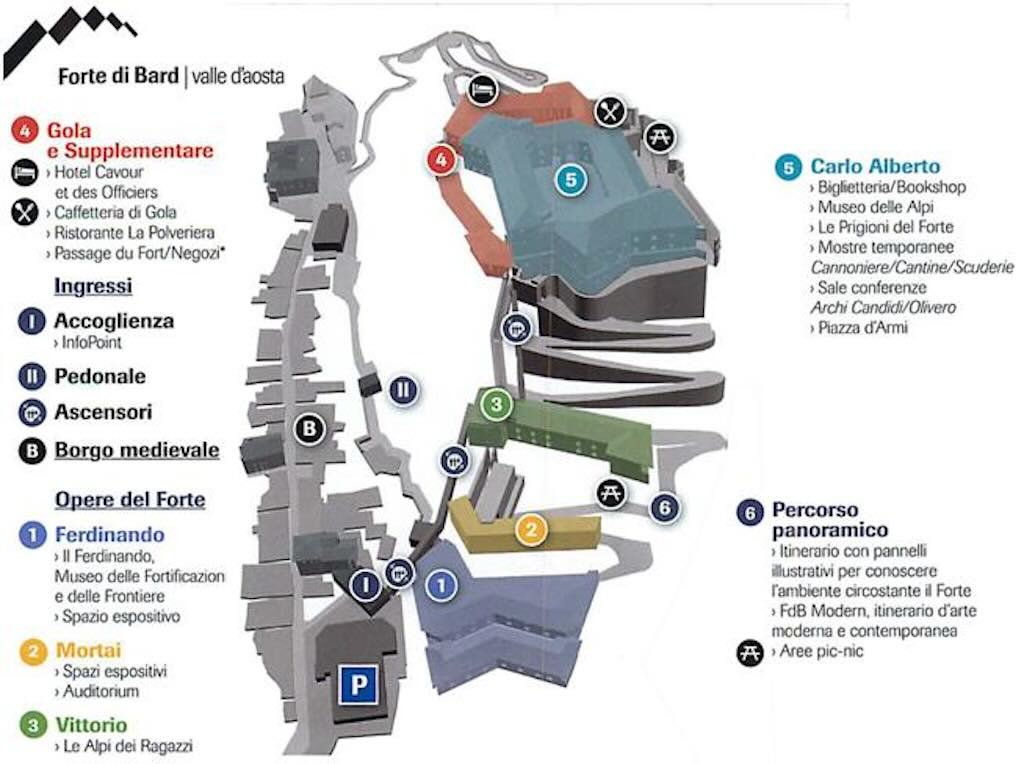

In 1827, afraid of another French assault, Carlo Felice (King of Sardegna) initiated the reconstruction of the fortress. He entrusted the project to Francesco Antonio Olivero, an officer of the Military Corps of Engineers. The reconstruction works took eight years, from 1830 to 1838. The new stronghold was formed of three groups of buildings, placed at different levels. The Ferdinando Opera at the bottom, the Vittorio Opera in the middle and the Carlo Alberto Opera at the top. This system of autonomous structures, fortified with artillery casements, was able to guarantee a reciprocal defence strategy in case of an enemy attack.

Above we can see the top of fort, the so-called Opera Alberto with the Piazza d’Armi (parade ground) and the Prigioni (prison cells). Most of the photos show the more impressive buildings seen when coming down the valley. Here on the right we have the road leading up to the fort, as seen when approaching the valley. The first building with the entrance is now a hotel.

The whole complex, with a total of 283 rooms, could accommodate up to 416 men (double that amount if the soldiers slept on a straw-laid floor). Approximately fifty cannons formed part of the weaponry and the storehouses could hold enough ammunition and food supplies to last three months.

At the end of the 1800s the fortress started to go into decline. No longer used for important wartime events it was initially employed as a penal settlement and then as a depository for ammunition.

Army property, the fortress fell into disuse in 1975 and was acquired by the Autonomous Region of Valle d’Aosta in 1990. They restored the fortress and the entire fortress compound is now a cultural centre, with a museum and exhibition spaces (and including accommodation and hospitality facilities).

The figures are impressive, with a surface area of more than 14,000 square meters, 2,000 square meters of internal courtyards, 9,000 square meters of roofing, 1,300 square meters of corridors, 283 rooms, 296 slits, and 806 steps.

Above we have an overview of the fort with the access paths, and below we have a graphic showing the main buildings, etc. It’s possible to walk up and down, but there is multi-storey parking and a series of three little lifts that take visitors to the top.

Royal Castle of Sarre

The existence of an early fortified house or simple tower is recorded since 1242 and is linked to a certain Jacques de Bard, founder of the Sarre family dynasty. It belonged to this family until 1364 when the last male heir died, subsequently Henri de Quart was granted the fief by Amadeus VI of Savoy. What we see today was built in 1710 on the ruins of the older fortress. The above photo is a little dated, because now the front terracing is covered in vines.

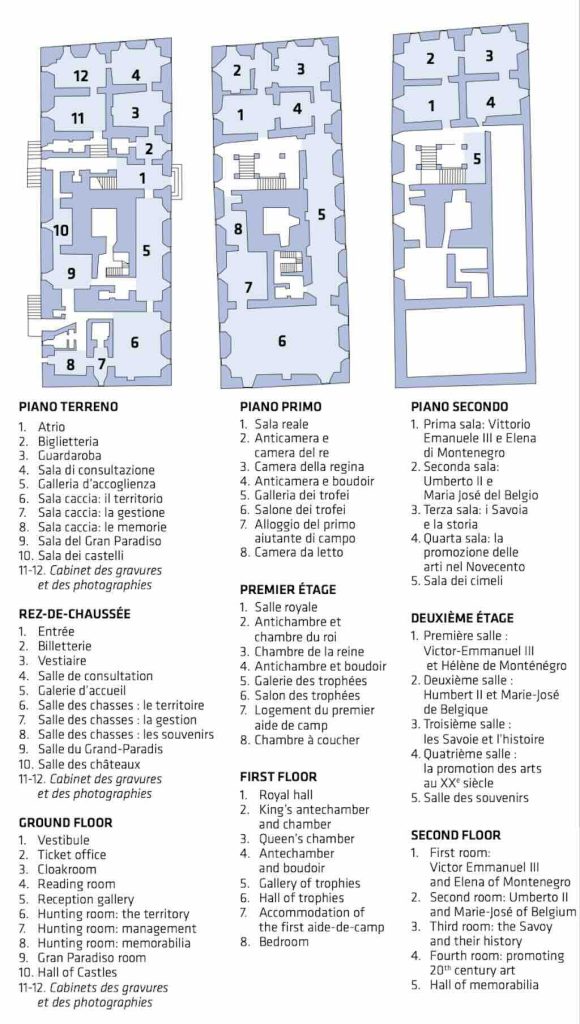

The building had several owners until the beginning of the 18th century, when it was bought by Baron Jean-François Ferrod, business partner of Count Perrone di San Martino (not sure which one) in the exploitation of the Ollomont copper mines. Owing to several risky investments, Ferrod went bankrupt, and the property was returned to the previous owners before again changing ownership several times. Finally it was purchased in 1869 by the King of Italy Victor Emmanuel II who had it refurbished and turned into his hunting lodge for expeditions in to the valleys of Cogne, Rhêmes and Valsavarenche.

Ferrod had demonstrate his wealth by having the castle completely rebuilt, giving it its current appearance. Only the tower survived. Victor Emmanuel II made several additions, including raising the tower and constructing new stables. Inside, the rooms were completely reconstructed and modernised. The curator of the Royal Palace in Milan was charged with furnishing the residence, for which he transferred furniture from other royal residences. From the castles’ towers, the Savoy sovereigns organised hunts of ibex and chamois in the huge game reserves that would ultimately be turned into the Gran Paradiso National Park in 1922, Italy’s first nature park.

Victor Emmanuel’s successor, Umberto I (1844-1900) also enjoyed hunting expeditions from his alpine castle. His wife, Queen Margherita, stayed at the castle only once during the summer of 1880 and, subsequently, preferred to stay at the nearby Savoy Castle that she had built near Gressoney-Saint-Jean.

The Princes of Piedmont Umberto II and Maria José were also regular visitors to Sarre. After having modernized the rooms in 1935, they used the castle as a seasonal residence for stays dedicated to their numerous Alpine excursions, but it was also the place where Princess Maria José took refuge with her children during the most difficult periods of the Second World War.

In the last years of his reign, Umberto I focused considerable attention on his Sarre residence, renewing its interiors. This included embellishing the reception rooms with memorabilia and works of art, and hanging hundreds of trophies of ibex and chamois. The gallery and hall of honour are dominated by decidedly unusual swirls of “hunting” decorations that create a certainly astonishing and uncommon final effect.

The castle remained the property of the Savoy family until 1972, when it was purchased by the Italian state. Since 1989, the castle has been owned by the Valle d’Aosta autonomous Region, and visits are with a guide.

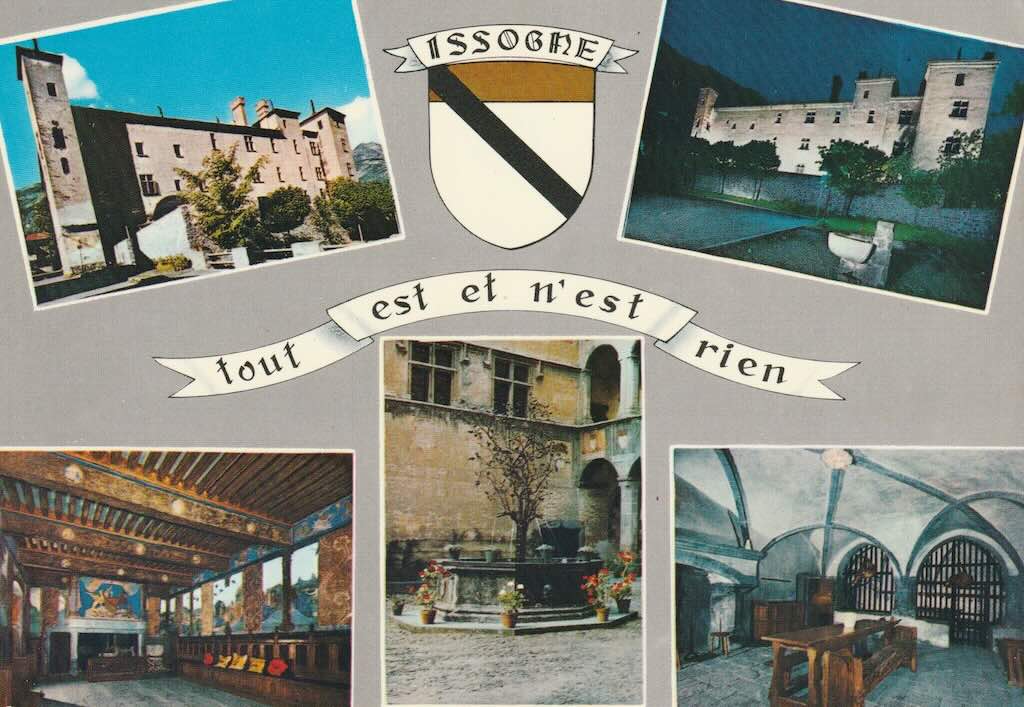

Castle of Issogne

I have prepared a separate post on this wonderful castle.

Saint-Pierre Castle

Saint-Pierre Castle, located on a rocky outcrop, offers one of the most picturesque views of the Aosta Valley. It is portrayed in numerous old prints and in drawings by famous authors such as Turner and John Ruskin. The first official mention of the castle is in the Charte des Franchises, granted to Count Thomas I of Savoy in 1191. During successive centuries it was home to several Aosta Valley noble families, including Sancto Petro, Vuillet and Roncas, with each making changes to the building.

In 1873, Federico Bollati, Superintendent of the Turin State Archives, bought the castle and, upon gaining the title of baron of Saint-Pierre, undertook restoration work directed by the Canavese engineer Camillo Boggio. He transformed the structure into an authentic feudal Middle Ages icon of the Aosta Valley. It is in eclectic neo-Gothic style and, taking inspiration from the castles built on the rocky spurs of the Rhine valley in southern Germany, Boggio built the four turrets at the corners of the central tower. This image is still one of the most evocative sites of the entire fortified panorama in the Aosta Valley.

The castle is now the exhibition site of the Regional Natural Science Museum and offers the visitor a double visit itinerary. Firstly, the history of the building, with the historical parts still visible, and secondly the Natural Science Museum, a journey through the Aosta Valley ecosystems. The nearby classroom has facilities for laboratories and activities for schools.

In fact the castle only has one room dedicated to its past, and all the other rooms are part of a natural history museum about the valley and more generally the Alps.

I must admit I was a bit disappointed because I expected to visit an old castle, and in creating the museum-exhibition much of the historic value of the castle has been lost (or hidden). A few of the rooms were interesting, but I guess it’s really designed as an educational exhibition targeted to children and young teenagers.